painting

Introduction

the expression of ideas and emotions, with the creation of certain aesthetic qualities, in a two-dimensional visual language. The elements of this language—its shapes, lines, colours, tones, and textures—are used in various ways to produce sensations of volume, space, movement, and light on a flat surface. These elements are combined into expressive patterns in order to represent real or supernatural phenomena, to interpret a narrative theme, or to create wholly abstract visual relationships. An artist's decision to use a particular medium, such as tempera (tempera painting), fresco (fresco painting), oil (oil painting), acrylic (acrylic painting), watercolour or other water-based paints, ink, gouache, encaustic (encaustic painting), or casein (casein painting), as well as the choice of a particular form, such as mural, easel, panel, miniature, manuscript illumination, scroll, screen or fan, panorama, or any of a variety of modern forms, is based on the sensuous qualities and the expressive possibilities and limitations of those options. The choices of the medium and the form, as well as the artist's own technique, combine to realize a unique visual image.

Earlier cultural traditions—of tribes, religions, guilds, royal courts, and states—largely controlled the craft, form, imagery, and subject matter of painting and determined its function, whether ritualistic, devotional, decorative, entertaining, or educational. Painters were employed more as skilled artisans than as creative artists. Later the notion of the “fine artist” developed in Asia and Renaissance Europe. Prominent painters were afforded the social status of scholars and courtiers; they signed their work, decided its design and often its subject and imagery, and established a more personal—if not always amicable—relationship with their patrons.

During the 19th century painters in Western societies began to lose their social position and secure patronage. Some artists countered the decline in patronage support by holding their own exhibitions and charging an entrance fee. Others earned an income through touring exhibitions of their work. The need to appeal to a marketplace had replaced the similar (if less impersonal) demands of patronage, and its effect on the art itself was probably similar as well. Generally, artists can now reach an audience only through commercial galleries and public museums, although their work may be occasionally reproduced in art periodicals. They may also be assisted by financial awards or commissions from industry and the state. They have, however, gained the freedom to invent their own visual language and to experiment with new forms and unconventional materials and techniques. For example, some painters have combined other media, such as sculpture, with painting to produce three-dimensional abstract designs. Other artists have attached real objects to the canvas in collage fashion or used electricity to operate coloured kinetic panels and boxes. Conceptual artists frequently express their ideas in the form of a proposal for an unrealizable project, while performance artists are an integral part of their own compositions. The restless endeavour to extend the boundaries of expression in Western art produces continuous international stylistic changes. The often bewildering succession of new movements in painting is further stimulated by the swift interchange of ideas by means of international art journals, traveling exhibitions, and art centres.

This article is concerned with the elements and principles of design in painting and with the various mediums, forms, imagery, subject matter, and symbolism employed or adopted or created by the painter. For the history of painting in ancient Egypt, see Egyptian art and architecture (art and architecture, Egyptian). The development of painting in different regions is treated in a number of articles; see Western painting (painting, Western); African art (art, African); Central Asian arts; Chinese painting; Islamic arts; Japanese art (arts, East Asian); Korean art (arts, East Asian); Native American art; Oceanic art and architecture (art and architecture, Oceanic); South Asian arts; and Southeast Asian arts. For the conservation and restoration of paintings, see art conservation and restoration. For a discussion of the forgery of works of art, see forgery. For a discussion of the role of painting and other arts in religion, as well as of the use of religious symbols in art, see religious symbolism and iconography. For information on other arts related to painting, see articles such as drawing; folk art; and printmaking.

Elements and principles of design

The design of a painting is its visual format: the arrangement of its lines, shapes, colours, tones, and textures into an expressive pattern. It is the sense of inevitability in this formal organization that gives a great painting its self-sufficiency and presence.

The colours and placing of the principal images in a design may be sometimes largely decided by representational and symbolic considerations. Yet it is the formal interplay of colours and shapes that alone is capable of communicating a particular mood, producing optical sensations of space, volume, movement, and light and creating forces of both harmony and tension, even when a painting's narrative symbolism is obscure.

Elements of design

Line

Each of the design elements has special expressive qualities. Line, for example, is an intuitive, primeval convention for representing things; the simple linear imagery of young children's drawings and prehistoric rock paintings is universally understood. The formal relationships of thick with thin lines, of broken with continuous, and of sinuous with jagged are forces of contrast and repetition in the design of many paintings in all periods of history. Variations in the painted contours of images also provide a direct method of describing the volume, weight, spatial position, light, and textural characteristics of things. The finest examples of this pictorial shorthand are found in Japanese ink painting, where an expressive economy and vitality of line is closely linked to a traditional mastery of calligraphy.

In addition to painted contours, a linear design is composed of all of the edges of tone and colour masses, of the axial directions of images, and of the lines that are implied by alignments of shapes across the picture. The manner in which these various kinds of line are echoed and repeated animates the design. The artist, whether acting consciously or intuitively, also places them in relationship to one another across the picture, so that they weave a unifying rhythmic network throughout the painting.

In addition to painted contours, a linear design is composed of all of the edges of tone and colour masses, of the axial directions of images, and of the lines that are implied by alignments of shapes across the picture. The manner in which these various kinds of line are echoed and repeated animates the design. The artist, whether acting consciously or intuitively, also places them in relationship to one another across the picture, so that they weave a unifying rhythmic network throughout the painting.Apart from the obvious associations of some linear patterns with particular actions—undulating lines suggesting buoyant movement, for instance—emotive sensations are produced by certain linear relationships. Thus, lines moving upward express feelings of joy and aspiration, those directing the eye downward evoke moods of sadness or defeat, while lines at angles opening to the right of a design are more agreeable and welcoming than those spreading outward to the left.

Shape and mass

Shape and mass, as elements of design, include all areas of different colour, tone, and texture, as well as individual and grouped images.

Children instinctively represent the things they see by geometrical symbols. Not only have sophisticated modern artists, such as Paul Klee (Klee, Paul) and Jean Dubuffet (Dubuffet, Jean), borrowed this untutored imagery, but the more arresting and expressive shapes and masses in most styles of painting and those to which most people intuitively respond will generally be found to have been clearly based on such archetypal forms. A square or a circle will tend to dominate a design and will therefore often be found at its focal centre—the square window framing Christ in Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, for example, the hovering “sun” in an Adolph Gottlieb abstract, or the halo encircling a Christian or Buddhist deity. A firmly based triangular image or group of shapes seems reassuring, even uplifting, while the precarious balance implied by an inverted triangular shape or mass produces feelings of tension. Oval, lozenge, and rectangular forms suggest stability and protection and often surround vulnerable figures in narrative paintings.

There is generally a cellular unity, or “family likeness,” between the shapes and masses in a design similar to the visual harmony of all units to the whole observed in natural forms—the gills, fins, and scales in character with the overall shape of a fish, for example.

The negative spaces between shapes and masses are also carefully considered by the artist, since they can be so adjusted as to enhance the action and character of the positive images. They can be as important to the design as time intervals in music or the voids of an architectural facade.

colour

In many styles and periods of painting, the functions of colour are primarily decorative and descriptive, often serving merely to reinforce the expression of an idea or subject communicated essentially in terms of line and tone. In much of modern painting, however, the full-spectrum range of pigments available has allowed colour to be the primary expressive element.

The principal dimensions of colour in painting are the variables or attributes of hue, tone, and intensity. Red, yellow, and blue are the basic hues from which all others on the chromatic scale can be made by mixtures. These three opaque hues are the subtractive pigment primaries and should not be confused with the behaviour of the additive triads and mixtures of transparent, coloured light. Mixtures of primary pairs produce the secondary hues of orange, violet, and green. By increasing the amount of one primary in each of these mixtures, the tertiary colours of yellow-orange, orange-red, red-violet, violet-blue, blue-green, and green-yellow, respectively, are made. The primary colours, with their basic secondary and tertiary mixtures, can be usefully notated as the 12 segments of a circle. The secondary and tertiary colour segments between a pair of parent primaries can then be seen to share a harmonious family relationship with one another—the yellow-orange, orange, and orange-red hues that lie between yellow and red, for example.

The principal dimensions of colour in painting are the variables or attributes of hue, tone, and intensity. Red, yellow, and blue are the basic hues from which all others on the chromatic scale can be made by mixtures. These three opaque hues are the subtractive pigment primaries and should not be confused with the behaviour of the additive triads and mixtures of transparent, coloured light. Mixtures of primary pairs produce the secondary hues of orange, violet, and green. By increasing the amount of one primary in each of these mixtures, the tertiary colours of yellow-orange, orange-red, red-violet, violet-blue, blue-green, and green-yellow, respectively, are made. The primary colours, with their basic secondary and tertiary mixtures, can be usefully notated as the 12 segments of a circle. The secondary and tertiary colour segments between a pair of parent primaries can then be seen to share a harmonious family relationship with one another—the yellow-orange, orange, and orange-red hues that lie between yellow and red, for example.Local hues are the inherent and associative colours of things. In everyday life, familiar things are described by particular colours, and these often are identified by reference to familiar things; the green of grass and the grass green of paint, for instance. Although, as the Impressionists demonstrated, the inherent colours of forms in the real world are usually changed by effects of light and atmosphere, many of the great “primitive” and classical styles of representational painting are expressed in terms of local hues.

Tone is a colour's relative degree, or value, of lightness or darkness. The tonal pattern of a painting is shown in a monochrome reproduction. A painting dominated by dark colours, such as a Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), is in a low tonal key, while one painted in the pale range of a late Claude Monet (Monet, Claude) is said to be high keyed. The tonal range of pigments is too narrow for the painter to be able to match the brightest lights and deepest darks of nature. Therefore, in order to express effects of illumination and dense shadow, he must lower the overall tonal key of his design, thus intensifying the brightness value of his lightest pigment colours.

The Greco-Roman, Renaissance, and Neoclassical method of representing volume and space in painting was by a system of notated tonal values, the direction of each plane in the design being indicated by a particular degree of lightness or darkness. Each tonal value was determined by the angle at which a plane was meant to appear to turn away from an imaginary source of light. The tonal modeling, or shading, of forms was often first completed in a monochrome underpainting. This was then coloured with transparent washes of local hues, a technique similar to that of colour tinting a black-and-white photograph.

Each hue has an intrinsic tonal value in relation to others on the chromatic scale; orange is inherently lighter than red, for instance, and violet is darker than green. Any reversal of this natural tonal order creates a colour discord. An optical shock is therefore produced when orange is juxtaposed with pink (a lighter tone of red) or pale violet is placed against dark green. Such contrasts as these are deliberately created in paintings for the purpose of achieving these dramatic and disturbing effects.

The intensity of a colour is its degree of purity or hue saturation. The colour of a geranium, therefore, is said to be more intense, more highly saturated with pure orange-red than is mahogany. The pigment vermilion is orange-red at maximum intensity; the brown earth pigment burnt sienna is grayer and has a lower degree of orange-red saturation.

Intense hues are termed chromatic colours. The achromatic range is made up of hues reduced in intensity by the addition of white, making the tints, or pastel colours, such as cream and pink; or of black, producing the shades, or earth colours, such as mustard and moss green; or of both white and black, creating the neutralized hues, or colour-tinged grays, such as oatmeal and charcoal.

An achromatic colour will seem more intense if it is surrounded by neutralized hues or juxtaposed with its complementary colour. Complementaries are colour opposites. The complementary colour to one of the primary hues is the mixture of the other two; the complementary to red pigment, for example, is green—that is, blue mixed with yellow. The colour wheel shows that the tertiaries also have their colour opposites, the complementary to orange-red, for instance, being blue-green. Under clear light the complementary to any chroma, shade, or tint can be seen if one “fixates,” or stares at, one colour intently for a few seconds then looks at a neutral, preferably white, surface. The colour afterimage will appear to glow on the neutral surface. Mutual enhancement of colour intensity results from juxtaposing a complementary pair, red becoming more intensely red, for instance, and green more fiercely green when these are contiguous than either would appear if surrounded by harmonious hues. The 19th-century physicist Michel-Eugène Chevreul (Chevreul, Michel-Eugène) referred to this mutual exaltation of opposites as the law of simultaneous contrast. Chevreul's second law, of successive contrast, referred to the optical sensation that a complementary colour halo appears gradually to surround an intense hue. This complementary glow is superimposed on surrounding weaker colours, a gray becoming greenish when juxtaposed with red, reddish in close relationship with green, yellowish against violet, and so on.

An achromatic colour will seem more intense if it is surrounded by neutralized hues or juxtaposed with its complementary colour. Complementaries are colour opposites. The complementary colour to one of the primary hues is the mixture of the other two; the complementary to red pigment, for example, is green—that is, blue mixed with yellow. The colour wheel shows that the tertiaries also have their colour opposites, the complementary to orange-red, for instance, being blue-green. Under clear light the complementary to any chroma, shade, or tint can be seen if one “fixates,” or stares at, one colour intently for a few seconds then looks at a neutral, preferably white, surface. The colour afterimage will appear to glow on the neutral surface. Mutual enhancement of colour intensity results from juxtaposing a complementary pair, red becoming more intensely red, for instance, and green more fiercely green when these are contiguous than either would appear if surrounded by harmonious hues. The 19th-century physicist Michel-Eugène Chevreul (Chevreul, Michel-Eugène) referred to this mutual exaltation of opposites as the law of simultaneous contrast. Chevreul's second law, of successive contrast, referred to the optical sensation that a complementary colour halo appears gradually to surround an intense hue. This complementary glow is superimposed on surrounding weaker colours, a gray becoming greenish when juxtaposed with red, reddish in close relationship with green, yellowish against violet, and so on. Hues containing a high proportion of blue (the violet to green range) appear (perception) cooler than those with a high content of yellow or red (the green-yellow to red-violet range). This difference in the temperature of hues in a particular painting is, of course, relative to the range and juxtaposition of colours in the design. A green will appear cool if surrounded by intense yellow, while it will seem warm against blue-green. The optical (optics) tendency for warm colours to advance before cold had been long exploited by European and Asian painters as a method of suggesting spatial depth. Changes in temperature and intensity can be observed in the atmospheric effects of nature, where the colours of distant forms become cooler, grayer, and bluish, while foreground planes and features appear more intense and usually warmer in colour.

Hues containing a high proportion of blue (the violet to green range) appear (perception) cooler than those with a high content of yellow or red (the green-yellow to red-violet range). This difference in the temperature of hues in a particular painting is, of course, relative to the range and juxtaposition of colours in the design. A green will appear cool if surrounded by intense yellow, while it will seem warm against blue-green. The optical (optics) tendency for warm colours to advance before cold had been long exploited by European and Asian painters as a method of suggesting spatial depth. Changes in temperature and intensity can be observed in the atmospheric effects of nature, where the colours of distant forms become cooler, grayer, and bluish, while foreground planes and features appear more intense and usually warmer in colour.The apparent changes in a hue as it passes through zones of different colour has enabled painters in many periods to create the illusion of having employed a wide range of pigment hues with, in fact, the use of very few. And, although painters had applied many of the optical principles of colour behaviour intuitively in the past, the publication of research findings by Chevreul and others stimulated the Neo-Impressionists (Neo-Impressionism) and Post-Impressionists (Post-Impressionism) and the later Orphist (Orphism) and Op art painters to extend systematically the expressive possibilities of these principles in order to create illusions of volume and space and vibrating sensations of light and movement. Paul Cézanne (Cézanne, Paul), for example, demonstrated that subtle changes in the surface of a form and in its spatial relationship to others could be expressed primarily in facets of colour, modulated by varying degrees of tone, intensity, and temperature and by the introduction of complementary colour accents.

While the often-complex religious and cultural colour symbologies may be understood by very few, the emotional response to certain colour combinations appears to be almost universal. Optical harmonies and discords seem to affect everyone in the same way, if in varying degrees. Thus, an image repeated in different schemes of colour will express a different mood in each change.

While the often-complex religious and cultural colour symbologies may be understood by very few, the emotional response to certain colour combinations appears to be almost universal. Optical harmonies and discords seem to affect everyone in the same way, if in varying degrees. Thus, an image repeated in different schemes of colour will express a different mood in each change.Texture

Pointillism (a term given to the Neo-Impressionist (Neo-Impressionism) system of representing the shimmer of atmospheric light with spots of coloured pigment) produced an overall granular texture. As an element of design, texture includes all areas of a painting enriched or animated by vibrating patterns of lines, shapes, tones, and colours, in addition to the tactile textures created by the plastic qualities of certain mediums. Decorative textures may be of geometrical repeat patterns, as in much of Indian, Islamic, and medieval European painting and other art, or of representations of patterns in nature, such as scattered leaves, falling snow, and flights of birds.

Volume and space

The perceptual and conceptual methods of representing volume and space on the flat surface of a painting are related to the two levels of understanding spatial relationships in everyday life.

Perceptual space is the view of things at a particular time and from a fixed position. This is the stationary window view recorded by the camera and represented in the later periods of ancient Greek and Roman paintings and in most Western schools of painting since the Renaissance. Illusions of perceptual space are generally created by use of the linear perspectival system, based on the observations that objects appear to the eye to shrink and parallel lines and planes to converge as they approach the horizon, or viewer's eye level.

Young children and untrained artists, however, do not understand space in this way and represent it conceptually. Their paintings, therefore, show objects and surroundings independently of one another and from the views that best present their most characteristic features. The notion of scale in their pictures is also subjective, the relative size of things being decided by the artist either by their degree of emotional significance for him or by their narrative importance in the picture (interest perspective).

The conceptual, polydimensional representation of space has been used at some period in most cultures. In much of ancient Egyptian and Cretan painting, for example, the head and legs of a figure were shown in profile, but the eye and torso were drawn frontally. And in Indian, Islamic, and pre-Renaissance European painting, vertical forms and surfaces were represented by their most informative elevation view (as if seen from ground level), while the horizontal planes on which they stood were shown in isometric plan (as if viewed from above). This system produces the overall effect that objects and their surroundings have been compressed within a shallow space behind the picture plane.

By the end of the 19th century Cézanne had flattened the conventional Renaissance picture space, tilting horizontal planes so that they appeared to push vertical forms and surfaces forward from the picture plane and toward the spectator. This illusion of the picture surface as an integrated structure in projecting low relief was developed further in the early 20th century by the Cubists (Cubism). The conceptual, rotary perspective of a Cubist painting shows not only the components of things from different viewpoints but presents every plane of an object and its immediate surroundings simultaneously. This gives the composite impression of things in space that is gained by having examined their surfaces and construction from every angle.

In modern painting (Pop art), both conceptual and perceptual methods of representing space are often combined. And, where the orbital movement of forms—which has been a basic element in European design since the Renaissance—was intended to hold the spectator's attention within the frame, the expanding picture space in late 20th- and early 21st-century mural-size abstract paintings directs the eye outward to the surrounding wall, and their shapes and colours seem about to invade the observer's own territory.

In modern painting (Pop art), both conceptual and perceptual methods of representing space are often combined. And, where the orbital movement of forms—which has been a basic element in European design since the Renaissance—was intended to hold the spectator's attention within the frame, the expanding picture space in late 20th- and early 21st-century mural-size abstract paintings directs the eye outward to the surrounding wall, and their shapes and colours seem about to invade the observer's own territory. time and movement

Time and movement in painting are not restricted to representations of physical energy, but they are elements of all design. Part of the viewer's full experience of a great painting is to allow the arrangement of lines, shapes, and accents of tone or colour to guide the eye across the picture surface at controlled tempos and rhythmic directions. These arrangements contribute overall to the expression of a particular mood, vision, and idea.

Centuries before cinematography, painters attempted to produce kinetic sensations on a flat surface. A mural of 2000 BC in an Egyptian tomb at Beni Hasan, for instance, is designed as a continuous strip sequence of wrestling holds and throws, so accurately articulated and notated that it might be photographed as an animated film cartoon. The gradual unrolling of a 12th-century Japanese hand scroll produces the visual sensation of a helicopter flight along a river valley, while the experience of walking to the end of a long, processional Renaissance mural by Andrea Mantegna (Mantegna, Andrea) or Benozzo Gozzoli (Gozzoli, Benozzo) is similar to that of having witnessed a passing pageant as a standing spectator.

In the Eastern and Western narrative convention of continuous representation, various incidents in a story were depicted together within one design, the chief characters in the drama easily identified as they reappeared in different situations and settings throughout the painting. In Byzantine murals and in Indian and medieval manuscript paintings, narrative sequences were depicted in grid patterns, each “compartment” of the design representing a visual chapter in a religious story or a mythological or historical epic.

The Cubists (Cubism) aimed to give the viewer the time experience of moving around static forms in order to examine their volume and structure and their relationships to the space surrounding them. In paintings such as Nude Descending a Staircase, Girl Running on a Balcony, and Dog on Leash, Marcel Duchamp (Duchamp, Marcel) and Giacomo Balla (Balla, Giacomo) combined the Cubist technique of projected, interlocking planes with the superimposed time-motion sequences of cinematography. This technique enabled the artists to analyze the structural mechanics of forms, which are represented as moving in space past the viewer.

Principles of design

Because painting is a two-dimensional art, the flat pattern of lines and shapes is an important aspect of design, even for those painters concerned with creating illusions of great depth. And, since any mark made on the painting surface can be perceived as a spatial statement—for it rests upon it—there are also qualities of three-dimensional design in paintings composed primarily of flat shapes. Shapes in a painting, therefore, may be balanced with one another as units of a flat pattern and considered at the same time as components in a spatial design, balanced one behind another. A symmetrical balance of tone and colour masses of equal weight creates a serene and sometimes monumental design, while a more dynamic effect is created by an asymmetrical balance.

Geometrical shapes and masses are often the basic units in the design of both “flat patterns,” such as Byzantine and Islamic paintings, and “sculptural compositions,” such as Baroque and Neoclassical figure tableaux. The flat, overlapping squares, circles, and triangles that create the pattern of a Romanesque mural, for example, become the interlocking cubic, spherical, and pyramidal components that enclose the grouped figures and surrounding features in a Renaissance or a Neoclassical composition.

Geometrical shapes and masses are often the basic units in the design of both “flat patterns,” such as Byzantine and Islamic paintings, and “sculptural compositions,” such as Baroque and Neoclassical figure tableaux. The flat, overlapping squares, circles, and triangles that create the pattern of a Romanesque mural, for example, become the interlocking cubic, spherical, and pyramidal components that enclose the grouped figures and surrounding features in a Renaissance or a Neoclassical composition.An emphasis upon the proportion of the parts to the whole is a characteristic of Classical styles of painting. The Golden Mean (golden ratio), or Section, has been used as an ideal proportion on which to base the framework of lines and shapes in the design of a painting. The Renaissance mathematician Lucas Pacioli defined this aesthetically satisfying ratio as the division of a line so that the shorter part is to the longer as the longer is to the whole (approximately 8 to 13). His treatise (Divina proportione) influenced Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer (Dürer, Albrecht). The Neo-Impressionists Georges Seurat (Seurat, Georges) and Paul Signac (Signac, Paul) based the linear pattern of many of their compositions upon the principle of this “divine proportion.” Golden Mean proportions can be discovered in the design of many other styles of painting, although often they may have been created more by intuitive judgment than by calculated measurement.

Tension (stress) is created in paintings, as it is experienced in everyday life, by the anticipation of an event or by an unexpected change in the order of things. Optical and psychological tensions occur in passages of a design, therefore, when lines or shapes almost touch or seem about to collide, when a harmonious colour progression is interrupted by a sudden discord, or when an asymmetrical balance of lines, shapes, tones, or colours is barely held.

Contrasts in line, shape, tone, and colour create vitality; rectilinear shapes played against curvilinear, for instance, or warm colours against cool. Or a painting may be composed in contrasted overall patterns, superimposed in counterpoint to one another—a colour scheme laid across contrasting patterns of lines and tones, for example.

Design relationships between painting and other visual arts

The philosophy and spirit of a particular period in painting usually have been reflected in many of its other visual arts. The ideas and aspirations of the ancient cultures, of the Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassical periods of Western art and, more recently, of the 19th-century Art Nouveau and Secessionist movements were expressed in much of the architecture, interior design, furniture, textiles, ceramics, dress design, and handicrafts, as well as in the fine arts, of their times. Following the Industrial Revolution, with the redundancy of handcraftmanship and the loss of direct communication between the fine artist and society, idealistic efforts to unite the arts and crafts in service to the community were made by William Morris (Morris, William) in Victorian England and by the Bauhaus in 20th-century Germany. Although their aims were not fully realized, their influences, like those of the short-lived de Stijl (Stijl, De) and Constructivist (Constructivism) movements, have been far-reaching, particularly in architectural, furniture, and typographic design.

Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were painters, sculptors, and architects. Although no artists since have excelled in so wide a range of creative design, leading 20th-century painters expressed their ideas in many other mediums. In graphic design, for example, Pierre Bonnard (Bonnard, Pierre), Henri Matisse (Matisse, Henri), and Raoul Dufy (Dufy, Raoul) produced posters and illustrated books; André Derain (Derain, André), Fernand Léger (Léger, Fernand), Marc Chagall (Chagall, Marc), Mikhail Larionov (Larionov, Mikhail Fyodorovich), Robert Rauschenberg (Rauschenberg, Robert), and David Hockney (Hockney, David) designed for the theatre; Joan Miró (Miró, Joan), Pablo Picasso (Picasso, Pablo), and Chagall worked in ceramics; Georges Braque (Braque, Georges) and Salvador Dalí (Dalí, Salvador) designed jewelry; and Dalí, Hans Richter (Richter, Hans), and Andy Warhol (Warhol, Andy) made films. Many of these, with other modern painters, have also been sculptors and printmakers and have designed for textiles, tapestries, mosaics, and stained glass, while there are few mediums of the visual arts that Picasso did not work in and revitalize.

In turn, painters have been stimulated by the imagery, techniques, and design of other visual arts. One of the earliest of these influences was possibly from the theatre, where the ancient Greeks are thought to have been the first to employ the illusions of optical perspective. The discovery or reappraisal of design techniques and imagery in the art forms and processes of other cultures has been an important stimulus to the development of more recent styles of Western painting, whether or not their traditional significance have been fully understood. The influence of Japanese woodcut prints on Synthetism and the Nabis, for example, and of African sculpture on Cubism and the German Expressionists (Expressionism) helped to create visual vocabularies and syntax with which to express new visions and ideas. The invention of photography introduced painters to new aspects of nature, while eventually prompting others to abandon representational painting altogether. Painters of everyday life, such as Edgar Degas (Degas, Edgar), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de), Édouard Vuillard (Vuillard, Édouard), and Bonnard, exploited the design innovations of camera cutoffs, close-ups, and unconventional viewpoints in order to give the spectator the sensation of sharing an intimate picture space with the figures and objects in the painting.

Techniques and methods

Whether a painting reached completion by careful stages or was executed directly by a hit-or-miss alla prima method (in which pigments are laid on in a single application) was once largely determined by the ideals and established techniques of its cultural tradition. For example, the medieval European illuminator's painstaking procedure, by which a complex linear pattern was gradually enriched with gold leaf and precious pigments, was contemporary with the Song (Song dynasty) Chinese Chan ( Zen) practice of immediate, calligraphic brush painting, following a contemplative period of spiritual self-preparation. More recently, the artist has decided the technique and working method best suited to his aims and temperament. In France in the 1880s, for instance, Seurat might be working in his studio on drawings, tone studies, and colour schemes in preparation for a large composition at the same time that, outdoors, Monet was endeavouring to capture the effects of afternoon light and atmosphere, while Cézanne analyzed the structure of the mountain Sainte-Victoire with deliberated brush strokes, laid as irrevocably as mosaic tesserae (small pieces, such as marble or tile).

Whether a painting reached completion by careful stages or was executed directly by a hit-or-miss alla prima method (in which pigments are laid on in a single application) was once largely determined by the ideals and established techniques of its cultural tradition. For example, the medieval European illuminator's painstaking procedure, by which a complex linear pattern was gradually enriched with gold leaf and precious pigments, was contemporary with the Song (Song dynasty) Chinese Chan ( Zen) practice of immediate, calligraphic brush painting, following a contemplative period of spiritual self-preparation. More recently, the artist has decided the technique and working method best suited to his aims and temperament. In France in the 1880s, for instance, Seurat might be working in his studio on drawings, tone studies, and colour schemes in preparation for a large composition at the same time that, outdoors, Monet was endeavouring to capture the effects of afternoon light and atmosphere, while Cézanne analyzed the structure of the mountain Sainte-Victoire with deliberated brush strokes, laid as irrevocably as mosaic tesserae (small pieces, such as marble or tile).The kind of relationship established between artist and patron, the site and subject matter of a painting commission, and the physical properties of the medium employed may also dictate working procedure. Peter Paul Rubens (Rubens, Peter Paul), for example, followed the businesslike 17th-century custom of submitting a small oil sketch, or modella, for his client's approval before carrying out a large-scale commission. Siting problems peculiar to mural painting, such as spectator eye level and the scale, style, and function of a building interior, had first to be solved in preparatory drawings and sometimes with the use of wax figurines or scale models of the interior. Scale working drawings are essential to the speed and precision of execution demanded by quick-drying mediums, such as buon' fresco (painting) (see below) on wet plaster and acrylic resin on canvas. The drawings traditionally are covered with a network of squares, or “squared-up,” for enlarging on the surface of the support. Some modern painters prefer to outline the enlargement of a sketch projected directly onto the support by epidiascope (a projector for images of both opaque and transparent objects).

In Renaissance painters' workshops, pupil assistants not only ground and mixed the pigments and prepared the supports and painting surfaces but often laid in the outlines and broad masses of the painting from the master's design and studies.

The inherent properties of its medium or the atmospheric conditions of its site may themselves preserve (art conservation and restoration) a painting. The wax solvent binder of encaustic paintings (painting) (see below) both retains the intensity and tonality of the original colours and protects the surface from damp. And, while prehistoric rock paintings and buon' frescoes are preserved by natural chemical action, the tempera pigments thought to be bound only with water on many ancient Egyptian murals are protected by the dry atmosphere and unvarying temperature of the tombs. It has, however, been customary to varnish oil paintings, both to protect the surface against damage by dirt and handling and to restore the tonality lost when some darker pigments dry out into a higher key. Unfortunately, varnish tends to darken and yellow with time into the sometimes disastrously imitated “Old Masters' mellow patina.” Once cherished, this amber-gravy film is now generally removed to reveal the colours in their original intensity. Glass began to replace varnish toward the end of the 19th century, when painters wished to retain the fresh, luminous finish of pigments applied directly to a pure white ground. The air-conditioning and temperature-control systems of modern museums make both varnishing and glazing unnecessary, except for older and more fragile exhibits.

The frames surrounding early altarpieces, icons, and cassone panels (painted panels on the chest used for a bride's household linen) were often structural parts of the support. With the introduction of portable easel pictures, heavy frames not only provided some protection against theft and damage but were considered an aesthetic enhancement to a painting, and frame making became a specialized craft. Gilded gesso moldings (consisting of plaster of paris and sizing that forms the surface for low relief) in extravagant swags of fruit and flowers certainly seem almost an extension of the restless, exuberant design of a Baroque or Rococo painting. A substantial frame also provided a proscenium (in a theatre, the area between the orchestra and the curtain) in which the picture was isolated from its immediate surroundings, thus adding to the window view illusion intended by the artist. Deep, ornate frames are unsuitable for many modern paintings, where the artist's intention is for his forms to appear to advance toward the spectator rather than be viewed by him as if through a wall aperture. In contemporary Minimal paintings, no effects of spatial illusionism are intended; and, in order to emphasize the physical shape of the support itself and to stress its flatness, these abstract, geometrical designs are displayed without frames or are merely edged with thin protective strips of wood or metal.

Mediums

By technical definition, mediums are the liquids added to paints to bind them and make them workable. They are discussed here, however, in the wider meaning of all the various paints, tools, supports, surfaces, and techniques employed by painters. The basis of all paints is variously coloured pigment, ground to a fine powder. The different expressive capacities and characteristic final surface texture of each medium are determined by the vehicle with which it is bound and thinned, the nature and surface preparation of the support, and the tools and technique with which it is handled.

Pigments are derived from various natural and artificial sources. The oldest and most permanent pigments are the blacks, prepared from bone and charcoal, and the clay earths, such as raw umber and raw sienna, which can be changed by heating into darker, warmer browns. In early periods of painting, readily available pigments were few. Certain intense hues were obtainable only from the rarer minerals, such as cinnabar (orange-red vermilion), lapis lazuli (violet-blue ultramarine), and malachite (green). These were expensive and therefore reserved for focal accents and important symbolic features in the design. The opening of trade routes and the manufacture of synthetic substitutes gradually extended the range of colours available to painters.

Tempera (tempera painting)

A tempera medium is dry pigment tempered with an emulsion and thinned with water. It is a very ancient medium, having been in constant use in most world cultures, until in Europe it was gradually superseded, during the Renaissance, by oil paints. Tempera was the original mural medium in the ancient dynasties of Egypt, Babylonia, Mycenean Greece, and China and was used to decorate the early Christian catacombs (catacomb). It was employed on a variety of supports, from the stone stelae (stela) (or commemorative pillars), mummy cases, and papyrus rolls of ancient Egypt to the wood panels of Byzantine icons (icon) and altarpieces (altarpiece) and the vellum leaves of medieval illuminated manuscripts (illuminated manuscript).

A tempera medium is dry pigment tempered with an emulsion and thinned with water. It is a very ancient medium, having been in constant use in most world cultures, until in Europe it was gradually superseded, during the Renaissance, by oil paints. Tempera was the original mural medium in the ancient dynasties of Egypt, Babylonia, Mycenean Greece, and China and was used to decorate the early Christian catacombs (catacomb). It was employed on a variety of supports, from the stone stelae (stela) (or commemorative pillars), mummy cases, and papyrus rolls of ancient Egypt to the wood panels of Byzantine icons (icon) and altarpieces (altarpiece) and the vellum leaves of medieval illuminated manuscripts (illuminated manuscript).True tempera is made by mixture with the yolk of fresh eggs, although manuscript illuminators often used egg white and some easel painters added the whole egg. Other emulsions have been used, such as casein glue with linseed oil, egg yolk with gum and linseed oil, and egg white with linseed or poppy oil. Individual painters have experimented with other recipes, but few of these have proved successful; all but William Blake (Blake, William)'s later tempera paintings on copper sheets, for instance, have darkened and decayed, and it is thought that he mixed his pigment with carpenter's glue.

Distemper is a crude form of tempera made by mixing dry pigment into a paste with water, which is thinned with heated glue in working or by adding pigment to whiting, a mixture of fine-ground chalk and size. It is used for stage scenery and full-size preparatory cartoons for murals and tapestries. When dry, its colours have the pale, mat, powdery quality of pastels, with a similar tendency to smudge. Indeed, damaged cartoons have been retouched with pastel chalks.

Egg tempera is the most durable form of the medium, being generally unaffected by humidity and temperature. It dries quickly to form a tough film that acts as a protective skin to the support. In handling, in its diversity of transparent and opaque effects, and in the satin sheen of its finish, it resembles the modern acrylic resin emulsion paints.

Traditional tempera painting is a lengthy process. Its supports are smooth surfaces, such as planed wood, fine set plaster, stone, paper, vellum, canvas, and modern composition boards of compressed wood or paper. Linen is generally glued to the surface of panel supports, additional strips masking the seams between braced wood planks. gesso, a mixture of plaster of paris (or gypsum) with size, is the traditional ground. The first layer is of gesso grosso, a mixture of coarse, unslaked plaster and size. This provides a rough, absorbent surface for 10 or more thin coats of gesso sotile, a smooth mixture of size and fine plaster previously slaked in water to retard drying. This laborious preparation results, however, in an opaque, brilliant white, light-reflecting surface, similar in texture to hard, flat icing sugar.

The design for a large tempera painting traditionally was executed in distemper on a thick paper cartoon. The outlines were pricked with a perforating wheel so that when the cartoon was laid on the surface of the support, the linear pattern was transferred by dabbing, or “pouncing,” the perforations with a muslin bag of powdered charcoal. The dotted contours traced through were then fixed in paint. Medieval tempera painters of panels and manuscripts made lavish use of gold leaf on backgrounds and for symbolic features, such as haloes and beams of heavenly light. Areas of the pounced design intended for gilding were first built up into low relief with gesso duro, the harder, less absorbent gesso compound used also for elaborate frame moldings. Background fields were often textured by impressing the gesso duro, before it set, with small, carved, intaglio wood blocks to create raised, pimpled, and quilted repeat patterns that glittered when gilded. Leaves of finely beaten gold were pressed onto a tacky mordant (adhesive compound) or over wet bole (reddish-brown earth pigment) that gave greater warmth and depth when the gilded areas were burnished.

The design for a large tempera painting traditionally was executed in distemper on a thick paper cartoon. The outlines were pricked with a perforating wheel so that when the cartoon was laid on the surface of the support, the linear pattern was transferred by dabbing, or “pouncing,” the perforations with a muslin bag of powdered charcoal. The dotted contours traced through were then fixed in paint. Medieval tempera painters of panels and manuscripts made lavish use of gold leaf on backgrounds and for symbolic features, such as haloes and beams of heavenly light. Areas of the pounced design intended for gilding were first built up into low relief with gesso duro, the harder, less absorbent gesso compound used also for elaborate frame moldings. Background fields were often textured by impressing the gesso duro, before it set, with small, carved, intaglio wood blocks to create raised, pimpled, and quilted repeat patterns that glittered when gilded. Leaves of finely beaten gold were pressed onto a tacky mordant (adhesive compound) or over wet bole (reddish-brown earth pigment) that gave greater warmth and depth when the gilded areas were burnished. Colours were applied with sable brushes in successive broad sweeps or washes of semitransparent tempera. These dried quickly, preventing the subtle tonal gradations possible with watercolour washes or oil paint; effects of shaded modelling had therefore to be obtained by a crosshatching technique of fine brush strokes. According to the Italian painter Cennino Cennini (Cennini, Cennino), the early Renaissance tempera painters laid the colour washes across a fully modelled monochrome underpainting in terre vert (olive-green pigment), a method developed later into the mixed mediums technique of tempera underpainting followed by transparent oil glazes.

Colours were applied with sable brushes in successive broad sweeps or washes of semitransparent tempera. These dried quickly, preventing the subtle tonal gradations possible with watercolour washes or oil paint; effects of shaded modelling had therefore to be obtained by a crosshatching technique of fine brush strokes. According to the Italian painter Cennino Cennini (Cennini, Cennino), the early Renaissance tempera painters laid the colour washes across a fully modelled monochrome underpainting in terre vert (olive-green pigment), a method developed later into the mixed mediums technique of tempera underpainting followed by transparent oil glazes.The luminous gesso base of a tempera painting, combined with the accumulative effect of overlaid colour washes, produces a unique depth and intensity of colour. Tempera paints dry lighter in value, but their original tonality can be restored by subsequent waxing or varnishing. Other characteristic qualities of a tempera painting, resulting from its fast drying property and disciplined technique, are its steely lines and crisp edges, its meticulous detail and rich linear textures, and its overall emphasis upon a decorative flat pattern of bold colour masses.

The great Byzantine tradition of tempera painting was developed in Italy in the 13th and 14th centuries by Duccio di Buoninsegna (Duccio) and Giotto (Giotto di Bondone). Their flattened picture space, generously enriched by fields and textures of gold leaf, was extended by the Renaissance depth perspectives in the paintings of Giovanni Bellini (Bellini, Giovanni), Piero della Francesca, Carlo Crivelli (Crivelli, Carlo), Sandro Botticelli (Botticelli, Sandro), and Vittore Carpaccio (Carpaccio, Vittore). By that time, oil painting was already challenging the primacy of tempera, Botticelli and some of his contemporaries apparently adding oil to the tempera emulsion or overglazing it in oil colour.

The great Byzantine tradition of tempera painting was developed in Italy in the 13th and 14th centuries by Duccio di Buoninsegna (Duccio) and Giotto (Giotto di Bondone). Their flattened picture space, generously enriched by fields and textures of gold leaf, was extended by the Renaissance depth perspectives in the paintings of Giovanni Bellini (Bellini, Giovanni), Piero della Francesca, Carlo Crivelli (Crivelli, Carlo), Sandro Botticelli (Botticelli, Sandro), and Vittore Carpaccio (Carpaccio, Vittore). By that time, oil painting was already challenging the primacy of tempera, Botticelli and some of his contemporaries apparently adding oil to the tempera emulsion or overglazing it in oil colour.Following the supremacy of the oil medium during succeeding periods of Western painting, the 20th century saw a revival of tempera techniques by such U.S. artists as Ben Shahn (Shahn, Ben), Andrew Wyeth (Wyeth, Andrew), and Jacob Lawrence (Lawrence, Jacob) and by the British painters Edward Wadsworth and Lucian Freud (Freud, Lucian). It would probably have been the medium also of the later hard-edge abstract painters had the new acrylic resin paints not proved more easily and quickly handled.

Fresco (fresco painting)

Fresco (Italian: “fresh”) is the traditional medium for painting directly onto a wall or ceiling. It is the oldest known painting medium, surviving in the prehistoric cave mural decorations and perfected in 16th-century Italy in the buon' fresco method.

The cave paintings are thought to date from about 20,000–15,000 BC. Their pigments probably have been preserved by a natural sinter process of rainwater seeping through the limestone rocks to produce saturated bicarbonate. The colours were rubbed across rock walls and ceilings with sharpened solid lumps of the natural earths (yellow, red, and brown ochre). Outlines were drawn with black sticks of wood charcoal. The discovery of mixing dishes suggests that liquid pigment mixed with fat was also used and smeared with the hand. The subtle tonal gradations of colour on animals painted in the Altamira and Lascaux (Lascaux Grotto) caves appear to have been dabbed in two stages with fur pads, natural variations on the rock surface being exploited to assist in creating effects of volume. Feathers and frayed twigs may have been used in painting manes and tails.

These were not composite designs but separate scenes and individual studies that, like graffiti drawings, were added at different times, often one above another, by various artists. Paintings from the Magdalenian period (Magdalenian culture) (c. 10,000 BC) exhibit astonishing powers of accurate observation and ability to represent movement. Women, warriors, horses, bison, bulls, boars, and ibex are depicted in scenes of ritual ceremony, battle, and hunting. Among the earliest images are imprinted and stencilled hands. Vigorous meanders, or “macaroni” linear designs, were traced with fingers dipped in liquid pigment.

Fresco secco

In the fresco secco, or lime-painting, method, the plastered surface of a wall is soaked with slaked lime. Lime-resistant pigments are applied swiftly before the plaster sets. Secco colours dry lighter than their tone at the time of application, producing the pale, mat, chalky quality of a distempered wall. Although the pigments are fused with the surface, they are not completely absorbed and may flake in time, as in sections of Giotto's 14th-century S. Francesco murals at Assisi. Secco painting was the prevailing medieval and early Renaissance medium and was revived in 18th-century Europe by artists such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista), François Boucher (Boucher, François), and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (Fragonard, Jean-Honoré).

Buon' fresco

Buon', or “true,” fresco is the most durable method of painting murals, since the pigments are completely fused with a damp plaster ground to become an integral part of the wall surface. The stone or brick wall is first prepared with a brown trullisatio scratch coat, or rough-cast plaster layer. This is then covered by the arricciato coat, on which the linear design of the preparatory cartoon is pounced (see above (painting)) or engraved by impressing the outlines into the moist, soft plaster with a bone or metal stylus. These lines were usually overworked in reddish sinopia pigment. A thin layer of fine plaster is then evenly spread, allowing the linear design to show through. Before this final intonaco ground sets, pigments thinned with water or slaked lime are applied rapidly with calf-hair and hog-bristle brushes; depth of colour is achieved by a succession of quick-drying glazes. Being prepared with slaked lime, the plaster becomes saturated with an aqueous solution of hydrate of lime, which takes up carbonic acid from the air as it soaks into the paint. Carbonate of lime is produced and acts as a permanent pigment binder. Pigment particles crystallize in the plaster, fusing it with the surface to produce the characteristic lustre of buon' fresco colours. When dry, these are mat and lighter in tone. Colours are restricted to the range of lime-resistant earth pigments. Mineral colours such as blue, affected by lime, are applied over earth pigment when the plaster is dry.

Buon', or “true,” fresco is the most durable method of painting murals, since the pigments are completely fused with a damp plaster ground to become an integral part of the wall surface. The stone or brick wall is first prepared with a brown trullisatio scratch coat, or rough-cast plaster layer. This is then covered by the arricciato coat, on which the linear design of the preparatory cartoon is pounced (see above (painting)) or engraved by impressing the outlines into the moist, soft plaster with a bone or metal stylus. These lines were usually overworked in reddish sinopia pigment. A thin layer of fine plaster is then evenly spread, allowing the linear design to show through. Before this final intonaco ground sets, pigments thinned with water or slaked lime are applied rapidly with calf-hair and hog-bristle brushes; depth of colour is achieved by a succession of quick-drying glazes. Being prepared with slaked lime, the plaster becomes saturated with an aqueous solution of hydrate of lime, which takes up carbonic acid from the air as it soaks into the paint. Carbonate of lime is produced and acts as a permanent pigment binder. Pigment particles crystallize in the plaster, fusing it with the surface to produce the characteristic lustre of buon' fresco colours. When dry, these are mat and lighter in tone. Colours are restricted to the range of lime-resistant earth pigments. Mineral colours such as blue, affected by lime, are applied over earth pigment when the plaster is dry.The intonaco coat is laid only across an area sufficient for painting before the plaster sets. The joins between each successive “day piece” are sometimes visible. Alterations must be made by immediate washing or scraping; minor retouching to set plaster is possible with casein or egg tempera, but major corrections necessitate breaking away the intonaco and replastering. The swift execution demanded stimulates bold designs in broad masses of colour with a calligraphic vitality of brush marks.

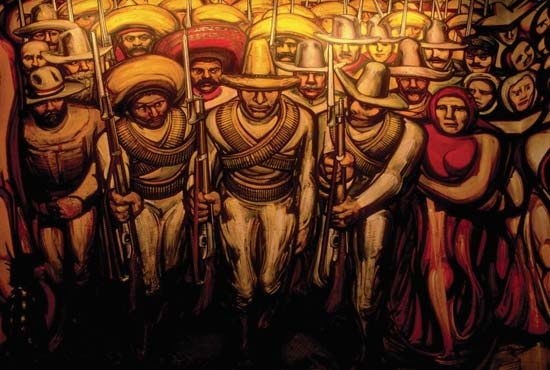

No ancient Greek buon' frescoes now exist, but forms of the technique survive in the Pompeian villas of the 1st century AD and earlier, in Chinese tombs at Liaoyang, Manchuria, and in the 6th-century Indian caves at Ajanta (Ajanta Caves). Among the finest buon' fresco murals are those by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel and by Raphael in the Stanze of the Vatican. Other notable examples from the Italian Renaissance can be seen in Florence: painted by Andrea Orcagna (Orcagna, Andrea) in the Museo dell'Opera di Sta. Croce, by Gozzoli in the chapel of the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, and by Domenico Ghirlandaio (Ghirlandaio, Domenico) in the church of Sta. Maria Novella. Buon' fresco painting is unsuited to the damp, cold climate of northern countries, and there is now some concern for the preservation of frescoes in the sulfurous atmosphere of even many southern cities. Buon' fresco was successfully revived by the Mexican mural painters Diego Rivera (Rivera, Diego), José Orozco (Orozco, José Clemente), and Rufino Tamayo (Tamayo, Rufino).

sgraffito

Sgraffito (Italian graffiare, “to scratch”) is a form of fresco painting for exterior walls. A rough plaster undercoat is followed by thin plaster layers, each stained with a different lime-fast colour. These coats are covered by a fine-grain mortar finishing surface. The plaster is then engraved with knives and gouges at different levels to reveal the various coloured layers beneath. The sintered-lime process binds the colours. The surface of modern sgraffito frescoes is often enriched with textures made by impressing nails and machine parts, combined with mosaics of stone, glass, plastic, and metal tesserae.

Sgraffito has been a traditional folk art in Europe since the Middle Ages and was practiced as a fine art in 13th-century Germany. It has been recently revived in northern Europe.

Oil

Oil paints (oil painting) are made by mixing dry pigment powder with refined linseed oil to a paste, which is then milled in order to disperse the pigment particles throughout the oil vehicle. According to the 1st-century Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, whose writings the Flemish painters Hubert and Jan van Eyck (Eyck, Jan van) are thought to have studied, the Romans used oil colours for shield painting. The earliest use of oil as a fine-art medium is generally attributed to 15th-century European painters, such as Giovanni Bellini (Bellini, Giovanni) and the van Eycks (Eyck, Jan van), who glazed oil colour over a glue-tempera underpainting. It is also thought probable, however, that medieval manuscript illuminators had been using oil glazes in order to achieve greater depth of colour and more subtle tonal transitions than their tempera medium allowed.

Oil paints (oil painting) are made by mixing dry pigment powder with refined linseed oil to a paste, which is then milled in order to disperse the pigment particles throughout the oil vehicle. According to the 1st-century Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, whose writings the Flemish painters Hubert and Jan van Eyck (Eyck, Jan van) are thought to have studied, the Romans used oil colours for shield painting. The earliest use of oil as a fine-art medium is generally attributed to 15th-century European painters, such as Giovanni Bellini (Bellini, Giovanni) and the van Eycks (Eyck, Jan van), who glazed oil colour over a glue-tempera underpainting. It is also thought probable, however, that medieval manuscript illuminators had been using oil glazes in order to achieve greater depth of colour and more subtle tonal transitions than their tempera medium allowed.Oils have been used on linen, burlap, cotton, wood, hide, rock, stone, concrete, paper, cardboard, aluminum, copper, plywood, and processed boards, such as masonite, pressed wood, and hardboard. The surface of rigid panels is traditionally prepared with gesso and that of canvas with one or more coats of white acrylic resin emulsion or with a coat of animal glue followed by thin layers of white-lead oil primer. Oil paints can be applied undiluted to these prepared surfaces or can be used thinned with pure gum turpentine or its substitute, white mineral spirit. The colours are slow drying; the safest dryer to speed the process is cobalt siccative.

An oil glaze is a transparent wash of pigment, traditionally thinned with an oleoresin or with stand oil (a concentrate of linseed oil). Glazes can be used to create deep, glowing shadows and to bring contrasted colours into closer harmony beneath a unifying tinted film. Scumbling is the technique of scrubbing an undiluted, opaque, and generally pale pigment across others for special textural effects or to raise the key of a dark-coloured area.

Hog-bristle brushes are used for much of the painting, with pointed, red sable-hair brushes generally preferred for outlines and fine details. Oils, however, are the most plastic and responsive of all painting mediums and can be handled with all manner of tools. The later works of Titian and Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), for example, appear to have been executed with thumbs, fingers, rags, spatulas, and brush handles. With these and other unconventional tools and techniques, oil painters create pigment textures ranging from delicate tonal modulations to unvarying, mechanical finishes and from clotted, impasto ridges of paint to barely perceptible stains.

Hog-bristle brushes are used for much of the painting, with pointed, red sable-hair brushes generally preferred for outlines and fine details. Oils, however, are the most plastic and responsive of all painting mediums and can be handled with all manner of tools. The later works of Titian and Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), for example, appear to have been executed with thumbs, fingers, rags, spatulas, and brush handles. With these and other unconventional tools and techniques, oil painters create pigment textures ranging from delicate tonal modulations to unvarying, mechanical finishes and from clotted, impasto ridges of paint to barely perceptible stains.The tempera-underpainting-oil-glaze technique was practiced into the 17th century. Artists such as Titian, El Greco (Greco, El), Rubens (Rubens, Peter Paul), and Diego Velázquez (Velázquez, Diego), however, used oil pigments alone and, employing a method similar to pastel painting, applied them directly to the brownish ground with which they had tinted the white priming. Contours and shadows were stained in streaks and washes of diluted paint, while lighter areas were created with dry, opaque scumbles, the tinted ground meanwhile providing the halftones and often remaining untouched for passages of local or reflected colour in the completed picture. This use of oil paint was particularly suited to expressing atmospheric effects and to creating chiaroscuro, or light and dark, patterns. It also encouraged a bravura handling of paint, where stabs, flourishes, lifts, and pressures of the brush economically described the most subtle changes of form, texture, and colour according to the influence exerted by the tinted ground through the varying thicknesses of overlaid pigment. This method was still practiced by the 19th-century painters, such as John Constable (Constable, John), J.M.W. Turner (Turner, J.M.W.), Eugène Delacroix (Delacroix, Eugène), and Honoré Daumier (Daumier, Honoré). The Impressionists (Impressionism), however, found the luminosity of a brilliant white ground essential to the alla prima technique with which they represented the colour intensities and shifting lights of their plein air (plein-air painting) (open air) subjects. Most oil paintings since then have been executed on white surfaces.

The rapid deterioration of Leonardo's 15th-century Last Supper (last restored 1978–99), which was painted in oils on plaster, possibly deterred artists from using the medium directly on a wall surface. And the likelihood of eventual warping also prohibited using the large number of braced wood panels required to make an alternative support for an extensive mural painting in oils. canvas, however, can be woven to any length, and, since an oil-painted surface is elastic, mural paintings could be executed in the studio and rolled and restretched on a wooden framework at the site or marouflaged (fastened with an adhesive) directly onto the wall surface. In addition to the immense studio canvases painted for particular sites by artists such as Jacopo Tintoretto (Tintoretto), Paolo Veronese (Veronese, Paolo), Delacroix (Delacroix, Eugène), Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes (Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre), and Monet (Monet, Claude), the use of canvas has made it possible for mural-size, modern oil paintings to be transported for exhibition to all parts of the world.

The rapid deterioration of Leonardo's 15th-century Last Supper (last restored 1978–99), which was painted in oils on plaster, possibly deterred artists from using the medium directly on a wall surface. And the likelihood of eventual warping also prohibited using the large number of braced wood panels required to make an alternative support for an extensive mural painting in oils. canvas, however, can be woven to any length, and, since an oil-painted surface is elastic, mural paintings could be executed in the studio and rolled and restretched on a wooden framework at the site or marouflaged (fastened with an adhesive) directly onto the wall surface. In addition to the immense studio canvases painted for particular sites by artists such as Jacopo Tintoretto (Tintoretto), Paolo Veronese (Veronese, Paolo), Delacroix (Delacroix, Eugène), Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes (Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre), and Monet (Monet, Claude), the use of canvas has made it possible for mural-size, modern oil paintings to be transported for exhibition to all parts of the world.The tractable nature of the oil medium has sometimes encouraged slipshod craftsmanship. Working over partly dry pigment or priming may produce a wrinkled surface. The excessive use of oil as a vehicle causes colours to yellow and darken, while cracking, blooming, powdering, and flaking can result from poor priming, overthinning with turpentine, or the use of varnish dryers and other spirits. Colour changes may also occur through the use of chemically incompatible pigment mixtures or from the fading of fugitive synthetic hues, such as the crimson lakes used by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Renoir, Pierre-Auguste).

watercolour

Watercolours are pigments ground with gum arabic and gall and thinned with water in use. Sable and squirrel (“camel”) hair brushes are used on white or tinted paper and card.

Watercolours are pigments ground with gum arabic and gall and thinned with water in use. Sable and squirrel (“camel”) hair brushes are used on white or tinted paper and card.Three hundred years before the late 18th-century English watercolourists, Albrecht Dürer (Dürer, Albrecht) had anticipated their technique of transparent colour washes in a remarkable series of plant studies and panoramic landscapes. Until the emergence of the English school, however, watercolour became a medium merely for colour tinting outlined drawings or, combined with opaque body colour to produce effects similar to gouache or tempera, was used in preparatory studies for oil paintings.

The chief exponents of the English method were Thomas Girtin (Girtin, Thomas), John Sell Cotman (Cotman, John Sell), John Robert Cozens (Cozens, John Robert), Richard Parkes Bonington (Bonington, Richard Parkes), David Cox, and Constable. Their contemporary J.M.W. Turner, however, true to his unorthodox genius, added white to his watercolour and used rags, sponges, and knives to obtain unique effects of light and texture. Victorian watercolourists, such as Birket Foster, used a laborious method of colour washing a monochrome underpainting, similar in principle to the tempera-oil technique. Following the direct, vigorous watercolours of the French Impressionists and Postimpressionists, however, the medium was established in Europe and America as an expressive picture medium in its own right. Notable 20th-century watercolourists have been Wassily Kandinsky (Kandinsky, Wassily), Paul Klee (Klee, Paul), Dufy (Dufy, Raoul), and Georges Rouault (Rouault, Georges); the U.S. artists Winslow Homer (Homer, Winslow), Thomas Eakins (Eakins, Thomas), Maurice Prendergast (Prendergast, Maurice Brazil), Charles Burchfield (Burchfield, Charles), John Marin (Marin, John), Lyonel Feininger (Feininger, Lyonel), and Jim Dine (Dine, Jim); and the English painters John and Paul Nash (Nash, Paul).

The chief exponents of the English method were Thomas Girtin (Girtin, Thomas), John Sell Cotman (Cotman, John Sell), John Robert Cozens (Cozens, John Robert), Richard Parkes Bonington (Bonington, Richard Parkes), David Cox, and Constable. Their contemporary J.M.W. Turner, however, true to his unorthodox genius, added white to his watercolour and used rags, sponges, and knives to obtain unique effects of light and texture. Victorian watercolourists, such as Birket Foster, used a laborious method of colour washing a monochrome underpainting, similar in principle to the tempera-oil technique. Following the direct, vigorous watercolours of the French Impressionists and Postimpressionists, however, the medium was established in Europe and America as an expressive picture medium in its own right. Notable 20th-century watercolourists have been Wassily Kandinsky (Kandinsky, Wassily), Paul Klee (Klee, Paul), Dufy (Dufy, Raoul), and Georges Rouault (Rouault, Georges); the U.S. artists Winslow Homer (Homer, Winslow), Thomas Eakins (Eakins, Thomas), Maurice Prendergast (Prendergast, Maurice Brazil), Charles Burchfield (Burchfield, Charles), John Marin (Marin, John), Lyonel Feininger (Feininger, Lyonel), and Jim Dine (Dine, Jim); and the English painters John and Paul Nash (Nash, Paul).In the “pure” watercolour technique, often referred to as the English method, no white or other opaque pigment is applied, colour intensity and tonal depth being built up by successive, transparent washes on damp paper. Patches of white paper are left unpainted to represent white objects and to create effects of reflected light. These flecks of bare paper produce the sparkle characteristic of pure watercolour. Tonal gradations and soft, atmospheric qualities are rendered by staining the paper when it is very wet with varying proportions of pigment. Sharp accents, lines, and coarse textures are introduced when the paper has dried. The paper should be of the type sold as “handmade from rags”; this is generally thick and grained. Cockling is avoided when the surface dries out if the dampened paper has been first stretched across a special frame or held in position during painting by an edging of tape.

ink

Ink is the traditional painting medium of China and Japan (arts, East Asian), where it has been used with long-haired brushes of wolf, goat, or badger on silk or absorbent paper. Asian black ink is a gum-bound carbon stick that is ground on rough stone and mixed with varying amounts of water to create a wide range of modulated tones or applied almost dry, with lightly brushed strokes, to produce coarser textures. The calligraphic brush technique is expressive of Zen Buddhist and Confucian (Confucianism) philosophies, brush-stroke formulas for the spiritual interpretation of nature in painting dictating the use of the lifted brush tip for the “bone,” or “lean,” structure of things and the spreading belly of the hairs for their “flesh,” or “fat,” volumes. The East Asian artist poises the brush vertically above the paper and controls its rhythmic movements from the shoulder. Distant forms represented in landscapes painted on silk were sometimes brushed on from the reverse side.

Ink is the traditional painting medium of China and Japan (arts, East Asian), where it has been used with long-haired brushes of wolf, goat, or badger on silk or absorbent paper. Asian black ink is a gum-bound carbon stick that is ground on rough stone and mixed with varying amounts of water to create a wide range of modulated tones or applied almost dry, with lightly brushed strokes, to produce coarser textures. The calligraphic brush technique is expressive of Zen Buddhist and Confucian (Confucianism) philosophies, brush-stroke formulas for the spiritual interpretation of nature in painting dictating the use of the lifted brush tip for the “bone,” or “lean,” structure of things and the spreading belly of the hairs for their “flesh,” or “fat,” volumes. The East Asian artist poises the brush vertically above the paper and controls its rhythmic movements from the shoulder. Distant forms represented in landscapes painted on silk were sometimes brushed on from the reverse side.In the Western world, ink has been used rather more for preparatory studies and topographical and literary illustrations than as a medium for easel paintings. Western artists have generally combined ink washes with contours and textures in quill or steel pen. Among the finest of these are by Rembrandt, Nicolas Poussin (Poussin, Nicolas), Francisco Goya (Goya, Francisco de), Samuel Palmer (Palmer, Samuel), Constable, and Édouard Manet (Manet, Édouard). Claude Lorrain, Turner, and Daumier and, in the 20th century, Braque, Picasso, Reginald Marsh (Marsh, Reginald), Henri Michaux (Michaux, Henri), and John Piper are some of those who have exploited its unique qualities. Modern artists also use ballpoint and felt pens.

gouache

Gouache is opaque watercolour, known also as poster paint and designer's colour. It is thinned with water for applying, with sable- and hog-hair brushes, to white or tinted paper and card and, occasionally, to silk. Honey, starch, or acrylic is sometimes added to retard its quick-drying property. Liquid glue is preferred as a thinner by painters wishing to retain the tonality of colours (which otherwise dry slightly lighter in key) and to prevent thick paint from flaking. Gouache paints have the advantages that they dry out almost immediately to a mat finish and, if required, without visible brush marks. These qualities, with the capacities to be washed thinly or applied in thick impasto and a wide colour range that now includes fluorescent and metallic pigments, make the medium particularly suited to preparatory studies for oil and acrylic paintings. It is the medium that produces the suede finish and crisp lines characteristic of many Indian and Islamic miniatures, and it has been used in Western screen and fan decoration and by modern artists such as Rouault, Klee, Dubuffet, and Morris Graves (Graves, Morris).

Gouache is opaque watercolour, known also as poster paint and designer's colour. It is thinned with water for applying, with sable- and hog-hair brushes, to white or tinted paper and card and, occasionally, to silk. Honey, starch, or acrylic is sometimes added to retard its quick-drying property. Liquid glue is preferred as a thinner by painters wishing to retain the tonality of colours (which otherwise dry slightly lighter in key) and to prevent thick paint from flaking. Gouache paints have the advantages that they dry out almost immediately to a mat finish and, if required, without visible brush marks. These qualities, with the capacities to be washed thinly or applied in thick impasto and a wide colour range that now includes fluorescent and metallic pigments, make the medium particularly suited to preparatory studies for oil and acrylic paintings. It is the medium that produces the suede finish and crisp lines characteristic of many Indian and Islamic miniatures, and it has been used in Western screen and fan decoration and by modern artists such as Rouault, Klee, Dubuffet, and Morris Graves (Graves, Morris).Encaustic (encaustic painting)