Asparagales

plant order

Introduction

the Asparagus or orchid order of monocotyledonous (monocotyledon) flowering plants, containing 16–24 families, 1,122 genera, and more than 26,000 species.

the Asparagus or orchid order of monocotyledonous (monocotyledon) flowering plants, containing 16–24 families, 1,122 genera, and more than 26,000 species. Asparagales contains many garden plants and several types of bulbs and cut flowers that are commercially important. The most notable plants in temperate gardens include the spring-flowering Crocus and Hyacinthus and thousands of different cultivars of the summer-flowering Hemerocallis (daylily (day lily)), which has edible buds used in many East Asian recipes. Also important are Amaryllis, Hippeastrum, and narcissus. Aloe, a tropical African genera with elongate, succulent (fleshy) leaves, is a favoured houseplant and is used medicinally. Other plants with edible parts include onion (Allium cepa), garlic (A. sativum), and their relatives the leek (A. ampeloprasum) and shallot (A. cepa). Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) is prized as a vegetable. The flavouring vanilla is an extract of the fruit of the Vanilla orchid (although most vanilla flavouring is now synthetically produced). saffron is a spice obtained from the stigmas of Crocus sativus.

Asparagales contains many garden plants and several types of bulbs and cut flowers that are commercially important. The most notable plants in temperate gardens include the spring-flowering Crocus and Hyacinthus and thousands of different cultivars of the summer-flowering Hemerocallis (daylily (day lily)), which has edible buds used in many East Asian recipes. Also important are Amaryllis, Hippeastrum, and narcissus. Aloe, a tropical African genera with elongate, succulent (fleshy) leaves, is a favoured houseplant and is used medicinally. Other plants with edible parts include onion (Allium cepa), garlic (A. sativum), and their relatives the leek (A. ampeloprasum) and shallot (A. cepa). Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) is prized as a vegetable. The flavouring vanilla is an extract of the fruit of the Vanilla orchid (although most vanilla flavouring is now synthetically produced). saffron is a spice obtained from the stigmas of Crocus sativus. Agave includes some of the largest members of Asparagales; the flower stalk of the century plant (A. americana) may reach 6 metres (20 feet) in height. These slow-growing plants flower once and die. Several species of Agave, notably A. sisalana, are cultivated for henequen and sisal fibres derived from their leaves. The bulky, asparagus-like inflorescences (inflorescence) (flower cluster) of plantation-grown plants in Mexico yield a rich juice that is fermented to produce pulque, mescal (mezcal), and tequila.

Agave includes some of the largest members of Asparagales; the flower stalk of the century plant (A. americana) may reach 6 metres (20 feet) in height. These slow-growing plants flower once and die. Several species of Agave, notably A. sisalana, are cultivated for henequen and sisal fibres derived from their leaves. The bulky, asparagus-like inflorescences (inflorescence) (flower cluster) of plantation-grown plants in Mexico yield a rich juice that is fermented to produce pulque, mescal (mezcal), and tequila.Many yuccas (yucca) are small plants, but the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) typically attains a height greater than 10 metres (nearly 33 feet) in California. Several other genera of this family are treelike. Yuccas contain saponins, compounds that foam when mixed with water; they are one of the original sources of natural detergents.

Organization

Few groups of angiosperms (angiosperm) are in such taxonomic ferment as Asparagales. Beginning in the 1980s, significant rearrangements were made by the Swedish botanist Rolf Dahlgren and his colleagues to the genera and families that were formerly recognized in the subclass Liliidae in the Cronquist botanical classification system. Under the reorganization, families such as Philydraceae, Pontederiaceae, Haemodoraceae, and Velloziaceae have been excluded and the remaining taxa have been realigned into three substantially different orders: Dioscoreales (the yam order), Liliales (the lily order), and Asparagales.

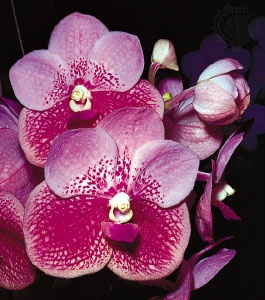

Within Asparagales, two major groups of families are now recognized, based primarily on molecular evidence but also on patterns of pollen development. The “lower Asparagales” include Orchidaceae (the orchid family, with more than 22,000 species in nearly 1,000 genera), Asteliaceae (the silver spear family, with 36 species in 2–4 genera), Hypoxidaceae (the star lily family, with 100–220 species in 7–9 genera), Iridaceae (the Iris family, with more than 1,500 species in some 80 genera), Hemerocallidaceae (the daylily (day lily) family 【which includes the former family Anthericaceae】, with 85 species in 19 genera), Asphodelaceae (the Aloe family, with 785 species in 15 genera), and Xanthorrhoeaceae (the grass tree family, with 30 species in 1 genus), plus a number of small families (e.g., Blandfordiaceae, Lanariaceae, Boryaceae, Ixioliriaceae, Tecophilaeaceae, Doryanthaceae, and Xeronemataceae).

Within Asparagales, two major groups of families are now recognized, based primarily on molecular evidence but also on patterns of pollen development. The “lower Asparagales” include Orchidaceae (the orchid family, with more than 22,000 species in nearly 1,000 genera), Asteliaceae (the silver spear family, with 36 species in 2–4 genera), Hypoxidaceae (the star lily family, with 100–220 species in 7–9 genera), Iridaceae (the Iris family, with more than 1,500 species in some 80 genera), Hemerocallidaceae (the daylily (day lily) family 【which includes the former family Anthericaceae】, with 85 species in 19 genera), Asphodelaceae (the Aloe family, with 785 species in 15 genera), and Xanthorrhoeaceae (the grass tree family, with 30 species in 1 genus), plus a number of small families (e.g., Blandfordiaceae, Lanariaceae, Boryaceae, Ixioliriaceae, Tecophilaeaceae, Doryanthaceae, and Xeronemataceae). The “higher Asparagales” are a natural group made up of 10 families, including Asparagaceae (the asparagus family, with 165–295 species in 2 genera), Ruscaceae (the lily of the valley family, 475 species in 26–28 genera), Hyacinthaceae (the grape hyacinth (grape-hyacinth) family, with 770–1,000 species in 41–70 genera), Agavaceae (the agave family, with 637 species in 23 genera), Laxmanniaceae (the cabbage tree family, with 178 species in 14–15 genera), Alliaceae (the onion and garlic family, with 795 species in 13 genera), and Amaryllidaceae (the daffodil family, with at least 800 species in 59 genera).

The “higher Asparagales” are a natural group made up of 10 families, including Asparagaceae (the asparagus family, with 165–295 species in 2 genera), Ruscaceae (the lily of the valley family, 475 species in 26–28 genera), Hyacinthaceae (the grape hyacinth (grape-hyacinth) family, with 770–1,000 species in 41–70 genera), Agavaceae (the agave family, with 637 species in 23 genera), Laxmanniaceae (the cabbage tree family, with 178 species in 14–15 genera), Alliaceae (the onion and garlic family, with 795 species in 13 genera), and Amaryllidaceae (the daffodil family, with at least 800 species in 59 genera).To a large extent, many of the families in Asparagales are defined primarily by DNA characters, and unique morphological characters are not obvious within families. For this reason, it is often difficult to identify the family into which a genus should be placed without laboratory analysis. However, as molecular evidence accumulates for distinguishing families and relationships within Asparagales, additional and new morphological features are being identified for recognizing these taxa.

Order growth characteristics

Members of Asparagales are typically perennial herbs with fleshy to fibrous stems (stem) arising from any of various types of underground storage or perennating organs. Some species of the predominantly African genera Dracaena (family Ruscaceae) and Protasparagus (a subgenus of Asparagus in family Asparagaceae) also may be regarded as vines, as they scramble through the forest or bush canopy, but neither has tendril-like adaptations for climbing. Annual plants are particularly rare. A few species of Sisyrinchium (family Iridaceae) are true annuals, though, with fleshy or fibrous roots, and some have become weedy in many parts of the world.

Members of Asparagales are typically perennial herbs with fleshy to fibrous stems (stem) arising from any of various types of underground storage or perennating organs. Some species of the predominantly African genera Dracaena (family Ruscaceae) and Protasparagus (a subgenus of Asparagus in family Asparagaceae) also may be regarded as vines, as they scramble through the forest or bush canopy, but neither has tendril-like adaptations for climbing. Annual plants are particularly rare. A few species of Sisyrinchium (family Iridaceae) are true annuals, though, with fleshy or fibrous roots, and some have become weedy in many parts of the world. Arborescent or shrubby Asparagales are unusual but are known, for example, in some species of Dracaena and Aloe (family Asphodelaceae), the latter having succulent leaves. The stems form fairly thick trunks composed of fibrous rather than woody tissue, a distinction that clearly differentiates them from true (dicotyledenous) trees. In the Americas, within the family Agavaceae, some species of Yucca, Agave, Furcraea, and Nolina have a similar arborescent habit, as do some species of Xanthorrhoea and Kingia of the Australian family Xanthorrhoeaceae.

Arborescent or shrubby Asparagales are unusual but are known, for example, in some species of Dracaena and Aloe (family Asphodelaceae), the latter having succulent leaves. The stems form fairly thick trunks composed of fibrous rather than woody tissue, a distinction that clearly differentiates them from true (dicotyledenous) trees. In the Americas, within the family Agavaceae, some species of Yucca, Agave, Furcraea, and Nolina have a similar arborescent habit, as do some species of Xanthorrhoea and Kingia of the Australian family Xanthorrhoeaceae.In the arborescent Asparagales a certain amount of stem girth may be due to secondary thickening from a lateral cambium layer (region of secondary growth). While the majority of monocotyledons do not form lateral meristems (meristem) (and thus secondary vascular tissues), they do undergo diffuse secondary growth by the continued division and enlargement of the ground parenchyma cells. A number of Asparagales species, however, undergo true secondary growth that involves a secondary meristem, the lateral cambium layer that forms below the secondary thickening meristem and extends to the base of the plant (i.e., it develops in the primary plant body that has already completed its elongation). Unlike the vascular cambiums in the dicotyledons, in which the secondary xylem develops internally and secondary phloem develops externally, the cambium of monocots divides and forms largely fibrous parenchymatous tissue toward the outside of the central pericycle, or cortex, and parenchyma and vascular bundles more or less typical of monocotyledonous bundles toward the inside. Usually the secondary bundles form radial rows in the secondary tissue.

A few members of Iridaceae in southern Africa, notably Nivenia, also have a shrubby habit. These genera have brittle woody stems. In spite of the similar pattern of secondary growth in these few monocots, it is likely that the condition arose independently in each group.

Epiphytes (epiphyte) abound in Orchidaceae but are rare in other families of Asparagales. Largely found in the subfamilies Orchidoideae and Epidendroideae, epiphytes are extraordinarily richly developed in the moist and wet tropics and have diversified into numerous genera and species, often with remarkable floral elaborations.

Specialized underground storage organs are particularly common in Alliaceae, Amaryllidaceae, and Iridaceae, the basal form probably being a rhizome—that is, a more or less prostrate stem that produces roots from the lower surface and a cluster of leaves from the apex. Bulbs (bulb) have evolved repeatedly in several lines and occur among many members of Asparagales. In Iridaceae, bulbs occur in some species of Iris and in the New World genera Tigridia, Eleutherine, Herbertia, and Trollius. Although the swollen and fleshy leaf bases or the protective bud scales (cataphylls) make up most of the bulb, a basal plate of stem tissue to which the leaves are attached is always present. Corms (corm), which are largely composed of stem tissue, characterize many members of Iridaceae and Tecophilaeaceae. Corms are usually dry, starchy, and surrounded by coverings (tunics) that are derived from the remains of decayed leaf bases or are produced by specialized leaves. The tunics may be fibrous, membranous, or even woody. While corms are generally compact, round, and replaced annually, tubers (tuber), which may also be composed of stem tissue, are often irregular in shape, lack special coverings, and persist for several years. The distinction between corms and tubers is not always obvious, however.

Specialized underground storage organs are particularly common in Alliaceae, Amaryllidaceae, and Iridaceae, the basal form probably being a rhizome—that is, a more or less prostrate stem that produces roots from the lower surface and a cluster of leaves from the apex. Bulbs (bulb) have evolved repeatedly in several lines and occur among many members of Asparagales. In Iridaceae, bulbs occur in some species of Iris and in the New World genera Tigridia, Eleutherine, Herbertia, and Trollius. Although the swollen and fleshy leaf bases or the protective bud scales (cataphylls) make up most of the bulb, a basal plate of stem tissue to which the leaves are attached is always present. Corms (corm), which are largely composed of stem tissue, characterize many members of Iridaceae and Tecophilaeaceae. Corms are usually dry, starchy, and surrounded by coverings (tunics) that are derived from the remains of decayed leaf bases or are produced by specialized leaves. The tunics may be fibrous, membranous, or even woody. While corms are generally compact, round, and replaced annually, tubers (tuber), which may also be composed of stem tissue, are often irregular in shape, lack special coverings, and persist for several years. The distinction between corms and tubers is not always obvious, however.As the scales (leaf bases) of underground bulbs of many Asparagales mature, buds may arise at their base to become bulblets (bulbil). As the parent scales disintegrate, these bulblets grow into new individuals. Similar offsets and buds on creeping rhizomes give rise to new plants in many species of this order. The tree onion, or Egyptian onion (a hybrid of Allium cepa), produces bulblets in place of flowers atop the flowering stalk. The European wild garlic (A. vineale) is a prolific producer of bulblets and has become a noxious weed even in North America. In the zephyr lily (Zephyranthes), seeds develop in the ovary without fertilization; they are, in essence, internal buds. In addition to these vegetative means of propagation, most members of the order produce seeds in the conventional manner.

Leaves (leaf)

The leaves of Asparagales species are characteristically strap-shaped and have parallel venation, which is typical of the monocotyledons. Iridaceae species stand out in having their leaf blade compressed in the same plane as the stem (equitant). Similar leaves also occur in a few Orchidaceae species. Orchid leaves are especially varied, and the leaf blades are absent in some genera with enlarged, succulent leaf bases.

Leaf succulence is a characteristic of most Asphodelaceae, a predominantly African family, many members of which are popular garden ornamentals, especially in warm, dry regions of the world. In addition, these fleshy leaves often have spines (confined to the margins or on the blades) and other types of ornamentation. In Old World Asparagus (which includes the former families Protasparagus and Myrsiphyllum), the true leaves are reduced to scales or spines, but terminal internodes of the stem form cladodes (leaflike, green organs that are filiform to variously laminate). Similar modifications characterize Ruscus and its close allies.

Leaf succulence is a characteristic of most Asphodelaceae, a predominantly African family, many members of which are popular garden ornamentals, especially in warm, dry regions of the world. In addition, these fleshy leaves often have spines (confined to the margins or on the blades) and other types of ornamentation. In Old World Asparagus (which includes the former families Protasparagus and Myrsiphyllum), the true leaves are reduced to scales or spines, but terminal internodes of the stem form cladodes (leaflike, green organs that are filiform to variously laminate). Similar modifications characterize Ruscus and its close allies.Flowers (flower)

The flowers of Asparagales are generally conspicuous and colourful; even when not large and brightly coloured, the inner and outer whorls of the perianth are typically petal-like, lacking the classic distinction between a green calyx and a variously coloured corolla. Because the only distinction between these two whorls is in their position, the segments of the perianth are usually called tepals rather than sepals and petals.

The flowers in the order are also extraordinarily varied, ranging from the small, inconspicuous, white-to-greenish, radially symmetric (actinomorphic) flowers of most Asparagaceae to the large, brightly coloured flowers of Orchidaceae (orchid), Amaryllidaceae, Hemerocallidaceae, and Iridaceae. A corona, which is a petaloid extension of some or all the tepals and perhaps most obvious as the trumpet portion of the flowers of Narcissus, occurs in some Amaryllidaceae.

In the majority of Asparagales species, the flowers are borne in terminal inflorescences on aerial stems that may carry normal or reduced leaves; if leafless, the flowering stem is often called a scape. Scapose inflorescences characterize many of the species that have bulbs and are typical of those Asparagales placed in Amaryllidaceae, Alliaceae, and Hyacinthaceae. The aerial stem is drastically shortened (reduced) in some Iridaceae and Orchidaceae. As a result, the flowers are borne at ground level, often with the ovary below ground and at the base of a long-tubed flower. Among the well-known stemless genera is Crocus of Iridaceae. Many more examples can be found in parts of the world with arid climates, such as southern Africa and the Middle East. Although the ovary may be underground at flowering, the flower stalk (peduncle) usually elongates so that the ovary is a short distance above the ground as the seeds develop and ripen.

In the majority of Asparagales species, the flowers are borne in terminal inflorescences on aerial stems that may carry normal or reduced leaves; if leafless, the flowering stem is often called a scape. Scapose inflorescences characterize many of the species that have bulbs and are typical of those Asparagales placed in Amaryllidaceae, Alliaceae, and Hyacinthaceae. The aerial stem is drastically shortened (reduced) in some Iridaceae and Orchidaceae. As a result, the flowers are borne at ground level, often with the ovary below ground and at the base of a long-tubed flower. Among the well-known stemless genera is Crocus of Iridaceae. Many more examples can be found in parts of the world with arid climates, such as southern Africa and the Middle East. Although the ovary may be underground at flowering, the flower stalk (peduncle) usually elongates so that the ovary is a short distance above the ground as the seeds develop and ripen.Deserving of special mention are umbels (an inflorescence in which the pedicels arise from about the same point to form a flat or rounded flower cluster), which characterize Amaryllidaceae and Alliaceae, and racemes (a simple inflorescence in which the flowers are borne on short stalks of about equal length at equal distances along an elongated axis and open in succession toward the apex), which are common in the order. The basal condition in Iridaceae is an inflorescence called a rhipidium, in which the flowers are clustered within two leafy bracts and are exserted one by one as the buds unfold. Many Iridaceae have spikes. Some species of Agavaceae are monocarpic: the entire plant dies after a single flowering, which produces hundreds of individual blossoms.

Although radial symmetry is the rule, most members of the Iridaceae subfamily Crocoideae and most Orchidaceae species have bilaterally symmetrical (zygomorphic) flowers. Another frequent condition in Orchidaceae is floral resupination, in which the ovary is twisted 180 degrees so that the undersurface of the ovary faces upward.

The basal condition in the male organs (androecium) is the presence of two whorls of three stamens each, these alternating with the perianth whorls. Anther dehiscence is typically longitudinal. Pollen grains are typically shed as monads, but all clustered into masses of grains called pollinia in the orchids.

The gynoecium comprises three carpels that are usually united. Styles may be free or, more often, united, and they may be either with discrete stigmatic lobes or simple, which is the most common condition in the Asparagales. In many members of the Iridaceae subfamily Iridoideae, the style is divided into three broad, flattened petaloid lobes, which are extended above into paired appendages (crests); the stigma is a small lobe on the undersurface of each style branch. Septal nectaries located within the walls of the ovary are widespread in the order; they are, however, rare in Orchidaceae where nectaries located on the tepals are frequent. Perigonal nectaries also characterize some groups of Iridaceae.

The ovary usually has three locules with axile placentation. Parietal placentation characterizes subfamilies Cypripedioideae and Orchidoideae of Orchidaceae but is rare elsewhere in Asparagales. Both inferior and superior ovaries occur in Asparagales.

Floral variation is closely correlated with pollination strategy. Further, floral zygomorphy and floral tube length are associated with restriction to specific pollinators. Nectaries located on the tepals (perigonal nectaries) occur in some Iridaceae and in many Orchidaceae. They are either superficial or confined to folds, pouches, or spurs, the latter being especially characteristic of Orchidaceae. Septal nectaries, embedded in the ovary, occur in many other Asparagales.

pollination

The variety of insect pollinators (the principal animal pollinator of Asparagales) is extensive, but the most frequent is the bee. Among the adaptations that the flowers have developed for this mode of pollination are bright colours (except reds, which bees cannot distinguish from black), contrasting markings (nectar guides), and often a sweet odour. In some Orchidaceae—for example, Ophrys—the colouring and shape of the labellum (lowest of three petals) resembles a female bee of a particular species; the flower is pollinated during pseudocopulation by the male bee. In many American genera of Orchidaceae and Iridaceae, sweet (sugar-containing) nectar may be supplemented by oils secreted by stalked glands in the nectaries. Some of the Neotropical Orchidaceae that produce aromatic compounds are pollinated by male bees, which utilize them for marking territory and probably in mating behaviour; the nectar or pollen or both may be the reward offered. Carrion fly pollination is relatively uncommon, but in Africa pollination by flies of several families with long proboscises is common. Flowers with a long, thin perianth tube are typical of this pollination syndrome, especially in Iridaceae.

The variety of insect pollinators (the principal animal pollinator of Asparagales) is extensive, but the most frequent is the bee. Among the adaptations that the flowers have developed for this mode of pollination are bright colours (except reds, which bees cannot distinguish from black), contrasting markings (nectar guides), and often a sweet odour. In some Orchidaceae—for example, Ophrys—the colouring and shape of the labellum (lowest of three petals) resembles a female bee of a particular species; the flower is pollinated during pseudocopulation by the male bee. In many American genera of Orchidaceae and Iridaceae, sweet (sugar-containing) nectar may be supplemented by oils secreted by stalked glands in the nectaries. Some of the Neotropical Orchidaceae that produce aromatic compounds are pollinated by male bees, which utilize them for marking territory and probably in mating behaviour; the nectar or pollen or both may be the reward offered. Carrion fly pollination is relatively uncommon, but in Africa pollination by flies of several families with long proboscises is common. Flowers with a long, thin perianth tube are typical of this pollination syndrome, especially in Iridaceae.Birds (bird) are also an important but less frequent pollinator. Pollination by sunbirds (sunbird) is relatively common in African Asphodelaceae, such as Aloe and Kniphofia, and Iridaceae, notably in Gladiolus and Watsonia, and in some Australian genera, such as Blandfordia in Blandfordiaceae. In the New World, hummingbird pollination occurs in several Amaryllidaceae, some Agavaceae, including Beschorneria and Polianthes, and a few Iridaceae, as in Rigidella. Bird-pollinated species generally have a red perianth, a long, wide tube, and exserted stamens and stigmas. Despite the great floral diversity in Orchidaceae, bird pollination is rare.

Pollination by hawk moths (hawk moth) occurs in many orchids that have long nectar-bearing spurs and in some Iridaceae with long perianth tubes. In addition, the flowers have a white or yellow perianth and a strong, sweet scent. The Yucca (Agavaceae) has an unusual pollination syndrome: females of the moth Tegeticula lay eggs in the ovary and then carefully transfer pollen to the stigmas. Bat pollination is rare in Asparagales, but it has been recorded in some species of Agavaceae.

Fruits and seeds

Fruits (fruit) of Asparagales are mostly dry, dehiscent capsules or berries. Fleshy fruits (berries) are found in many taxa of the Northern Hemisphere (Convallaria, Smilacina, and Polygonatum), in Ruscus and its close allies of Eurasia, and in Asparagus (including Protasparagus and Myrsiphyllum), a largely African alliance. A few tropical members also have fleshy fruits, notably Dianella, which has glossy violet berries. Orchidaceae rarely have fleshy fruits, but the genus Vanilla is a noteworthy exception. It is cultivated in the tropics for its podlike berries, which yield the flavouring vanilla.

Fruits (fruit) of Asparagales are mostly dry, dehiscent capsules or berries. Fleshy fruits (berries) are found in many taxa of the Northern Hemisphere (Convallaria, Smilacina, and Polygonatum), in Ruscus and its close allies of Eurasia, and in Asparagus (including Protasparagus and Myrsiphyllum), a largely African alliance. A few tropical members also have fleshy fruits, notably Dianella, which has glossy violet berries. Orchidaceae rarely have fleshy fruits, but the genus Vanilla is a noteworthy exception. It is cultivated in the tropics for its podlike berries, which yield the flavouring vanilla.Seeds (seed and fruit) are especially variable in Asparagales and range in form from the basic globose to angular brownish or black seeds and in content from abundant hard endosperm (food reserves) to microscopic seeds without endosperm. The black colour of the seed coats in many Asparagales with capsular fruits is due to the presence of phytomelan, a carbonaceous substance, in the outer epidermis of the seed coat. These seeds are further specialized in that the tegmen (the derivative of the inner ovular integument) is completely crushed at maturity.

Seeds of Orchidaceae species are numerous and minute and usually lack endosperm. Only the outer layer of the outer integument generally persists as a membranous seed coat. Under natural conditions, orchid seeds germinate only after a symbiotic relationship has been established with a specialized fungus, which supplies nutrients to the developing seedling. Some Orchidaceae species have no chlorophyll (achlorophyllous) and remain saprophytic throughout their lives.

Fleshy seed coats, correlated with distribution by birds, are found in a few Iridaceae. Arils (fleshy seed appendages often derived from the ovule funiculus) also occur frequently. Seeds of Crinum and its close allies in Amaryllidaceae are large and fleshy, lack an outer seed coat (testa), and have lost their ability to become dormant. They germinate rapidly after being shed, sometimes even within the capsules, and the young seedlings develop rapidly from small bulbs, ensuring survival in the dry season, the onset of which may be quite soon after fruiting.

Ovules are basically crassinucellate (with ample nucellar tissue), but the tenuinucellate condition (without a parietal cell) has evolved repeatedly within several families. Both successive and simultaneous microsporogenesis (pollen production) occurs in Asparagales, and the resulting pollen grains are typically two-celled. Frequently, endosperm is formed by free-nuclear divisions, followed later by cell wall formation (nuclear endosperm formation), but helobial endosperm formation ( mitosis) occurs in several lineages. Endosperm generally consists of hemicelluloses in thick cell walls; the seeds typically contain considerable endosperm (except for Orchidaceae species) and small embryos. Embryos generally have a single terminal cotyledon and a tiny lateral, sometimes sunken primary bud (plumule).

Seed dispersal is not markedly developed in Asparagales, but the fleshy fruits and the fleshy or brightly coloured seeds of some Iridaceae are dispersed by birds. Very small seeds, or those with wings, as in Gladiolus, are adapted for wind dispersal. Elaiosomes (fleshy white arils) are found in a few genera, notably many species of Iris. These adaptations are thought to relate to dispersal by ants, which store the seeds in their nests and eat only the fleshy part. Adaptation for water dispersal is developed in a number of genera that have corky or spongy seed coats (e.g., Crinum) and some species of Iris. For the majority of the order, however, dispersal is poorly understood, and the predominant mechanisms may be passive.

Seed dispersal is not markedly developed in Asparagales, but the fleshy fruits and the fleshy or brightly coloured seeds of some Iridaceae are dispersed by birds. Very small seeds, or those with wings, as in Gladiolus, are adapted for wind dispersal. Elaiosomes (fleshy white arils) are found in a few genera, notably many species of Iris. These adaptations are thought to relate to dispersal by ants, which store the seeds in their nests and eat only the fleshy part. Adaptation for water dispersal is developed in a number of genera that have corky or spongy seed coats (e.g., Crinum) and some species of Iris. For the majority of the order, however, dispersal is poorly understood, and the predominant mechanisms may be passive.Flavonoids (flavonoid)

As might be expected from so large an order, Asparagales is very diverse in flavonoids (flavonoid), which have systematic importance only at the generic level. The unusual steroid saponins, however, characterize Asparagales to a remarkable degree. Chelidonic acid is characteristic of Asphodelaceae and Agavaceae but is probably absent in Orchidaceae. Chelidonic acid is rare or absent elsewhere in Asparagales and other monocotyledons. Characteristic alkaloids are found in several genera of Asparagales. Genera in the family Amaryllidaceae have a different series of alkaloids. Other alkaloid-containing Asparagales are the bulbous genera in the Hyacinthaceae, including highly toxic members such as Drimia (also called Urginea), Scilla, and Ornithogalum. Their toxicity stems from the cardiac glycosides (glycoside) (heart stimulants) they produce, which also occur in a few African genera of Iridaceae. Allylic sulfides, responsible for onion- or garlic-type odours, characterize Allium and other genera in the family Alliaceae.

As might be expected from so large an order, Asparagales is very diverse in flavonoids (flavonoid), which have systematic importance only at the generic level. The unusual steroid saponins, however, characterize Asparagales to a remarkable degree. Chelidonic acid is characteristic of Asphodelaceae and Agavaceae but is probably absent in Orchidaceae. Chelidonic acid is rare or absent elsewhere in Asparagales and other monocotyledons. Characteristic alkaloids are found in several genera of Asparagales. Genera in the family Amaryllidaceae have a different series of alkaloids. Other alkaloid-containing Asparagales are the bulbous genera in the Hyacinthaceae, including highly toxic members such as Drimia (also called Urginea), Scilla, and Ornithogalum. Their toxicity stems from the cardiac glycosides (glycoside) (heart stimulants) they produce, which also occur in a few African genera of Iridaceae. Allylic sulfides, responsible for onion- or garlic-type odours, characterize Allium and other genera in the family Alliaceae.- Størmer, Fredrik

- Stürgkh, Karl, Count von

- Stüssi, Rudolf

- Stœng Trêng

- Střední Slovensko

- Středočeský

- Suakoko

- Su-ao

- Suassuna, Ariano

- subarkose

- Subarnarekha River

- subatomic particle

- subbituminous coal

- subduction zone

- Subei Canal

- Subhas Chandra Bose

- Subiaco

- Subic Bay

- subjective idealism

- sublimation

- sublime

- Sublime Porte

- submachine gun

- submarine

- submarine canyon