Renaissance

European history

literally “rebirth,” the period in European civilization immediately following the Middle Ages, conventionally held to have been characterized by a surge of interest in classical learning and values. The Renaissance also witnessed the discovery and exploration of new continents, the substitution of the Copernican for the Ptolemaic system of astronomy, the decline of the feudal system and the growth of commerce, and the invention or application of such potentially powerful innovations as paper, printing, the mariner's compass, and gunpowder. To the scholars and thinkers of the day, however, it was primarily a time of the revival of classical learning and wisdom after a long period of cultural decline and stagnation.

A brief treatment of the Renaissance follows. For full treatment, see Europe, history of: The Renaissance (Europe, history of).

The term Middle Ages was coined by scholars in the 15th century to designate the interval between the downfall of the classical world of Greece and Rome and its rediscovery at the beginning of their own century, a revival in which they felt they were participating. Indeed, the notion of a long period of cultural darkness had been expressed by Petrarch even earlier. Events at the end of the Middle Ages, particularly beginning in the 12th century, set in motion a series of social, political, and intellectual transformations that culminated in the Renaissance. These included the increasing failure of the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire to provide a stable and unifying framework for the organization of spiritual and material life, the rise in importance of city-states and national monarchies, the development of national languages, and the breakup of the old feudal structures.

While the spirit of the Renaissance ultimately took many forms, it was expressed earliest by the intellectual movement called humanism. Humanism was initiated by secular men of letters rather than by the scholar-clerics who had dominated medieval intellectual life and had developed the Scholastic philosophy. Humanism began and achieved fruition first in Italy. Its predecessors were men like Dante and Petrarch, and its chief protagonists included Gianozzo Manetti, Leonardo Bruni, Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, Lorenzo Valla, and Coluccio Salutati. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 provided Humanism with a major boost, for many eastern scholars fled to Italy, bringing with them important books and manuscripts and a tradition of Greek scholarship.

Humanism had several significant features. First, it took human nature in all of its various manifestations and achievements as its subject. Second, it stressed the unity and compatibility of the truth found in all philosophical and theological schools and systems, a doctrine known as syncretism. Third, it emphasized the dignity of man. In place of the medieval ideal of a life of penance as the highest and noblest form of human activity, the Humanists looked to the struggle of creation and the attempt to exert mastery over nature. Finally, Humanism looked forward to a rebirth of a lost human spirit and wisdom. In the course of striving to recover it, however, the Humanists assisted in the consolidation of a new spiritual and intellectual outlook and in the development of a new body of knowledge. The effect of Humanism was to help men break free from the mental strictures imposed by religious orthodoxy, to inspire free inquiry and criticism, and to inspire a new confidence in the possibilities of human thought and creations.

From Italy the new Humanist spirit and the Renaissance it engendered spread north to all parts of Europe, aided by the invention of printing, which allowed literacy and the availability of classical texts to grow explosively. Foremost among northern Humanists was Desiderius Erasmus, whose Praise of Folly (1509) epitomized the moral essence of Humanism in its insistence on heartfelt goodness as opposed to formalistic piety. The intellectual stimulation provided by Humanists helped spark the Reformation, from which, however, many Humanists, including Erasmus, recoiled. By the end of the 16th century the battle of Reformation and Counter-Reformation had commanded much of Europe's energy and attention, while the intellectual life was poised on the brink of the Enlightenment.

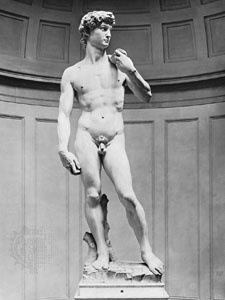

It was in art that the spirit of the Renaissance achieved its sharpest formulation. Art came to be seen as a branch of knowledge, valuable in its own right and capable of providing man with images of God and his creations as well as with insights into man's position in the universe. In the hands of men like Leonardo da Vinci it was even a science, a means for exploring nature and a record of discoveries. Art was to be based on the observation of the visible world and practiced according to mathematical principles of balance, harmony, and perspective, which were developed at this time. In the works of painters such as Masaccio, the brothers Lorenzetti, Fra Angelico, Botticelli, Perugino, Piero della Francesca, Raphael, and Titian; sculptors such as Pisano, Donatello, Verrocchio, Ghiberti, and Michelangelo; and architects such as Alberti, Brunelleschi, Palladio, Michelozzo, and Filarete, the dignity of man found expression in the arts.

In Italy the Renaissance proper was preceded by an important “proto-renaissance” in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, which drew inspiration from Franciscan radicalism. St. Francis had rejected the formal Scholasticism of the prevailing Christian theology and gone out among the poor praising the beauties and spiritual value of nature. His example inspired Italian artists and poets to take pleasure in the world around them. The work of the most famous artist of the proto-renaissance period, Giotto (Giotto di Bondone) (1266/67 or 1276–1337), reveals a new pictorial style that depends on clear, simple structure and great psychological penetration rather than on the flat, linear decorativeness and hierarchical compositions of his predecessors and contemporaries, such as the Florentine painter Cimabue and the Siennese painters Duccio and Simone Martini. The great poet Dante lived at about the same time as Giotto, and his poetry shows a similar concern with inward experience and the subtle shades and variations of human nature. Although his Divine Comedy belongs to the Middle Ages in its plan and ideas, its subjective spirit and power of expression look forward to the Renaissance. Petrarch and Boccaccio also belong to this proto-renaissance period, both through their extensive studies of Latin literature and through their writings in the vernacular. Unfortunately, the terrible plague of 1348 and subsequent civil wars submerged both the revival of humanistic studies and the growing interest in individualism and naturalism revealed in the works of Giotto and Dante. The spirit of the Renaissance did not surface again until the 15th century.

In 1401 a competition was held at Florence to award the commission for bronze doors to be placed on the baptistery of San Giovanni. Defeated by the goldsmith and painter Lorenzo Ghiberti, Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello left for Rome, where they immersed themselves in the study of ancient architecture and sculpture. When they returned to Florence and began to put their knowledge into practice, the rationalized art of the ancient world was reborn. The founder of Renaissance painting was Masaccio (1401–28). The intellectuality of his conceptions, the monumentality of his compositions, and the high degree of naturalism in his works mark Masaccio as a pivotal figure in Renaissance painting. The succeeding generation of artists—Piero della Francesca, Pollaiuolo, and Verrochio—pressed forward with researches into linear and aerial perspective and anatomy, developing a style of scientific naturalism.

In 1401 a competition was held at Florence to award the commission for bronze doors to be placed on the baptistery of San Giovanni. Defeated by the goldsmith and painter Lorenzo Ghiberti, Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello left for Rome, where they immersed themselves in the study of ancient architecture and sculpture. When they returned to Florence and began to put their knowledge into practice, the rationalized art of the ancient world was reborn. The founder of Renaissance painting was Masaccio (1401–28). The intellectuality of his conceptions, the monumentality of his compositions, and the high degree of naturalism in his works mark Masaccio as a pivotal figure in Renaissance painting. The succeeding generation of artists—Piero della Francesca, Pollaiuolo, and Verrochio—pressed forward with researches into linear and aerial perspective and anatomy, developing a style of scientific naturalism. The situation in Florence was uniquely favourable to the arts. The civic pride of Florentines found expression in statues of the patron saints commissioned from Ghiberti and Donatello for niches in the grain-market guildhall known as Or San Michele, and in the largest dome built since antiquity, placed by Brunelleschi on the Florence cathedral. The cost of construction and decoration of palaces, churches, and monasteries was underwritten by wealthy merchant families, chief among whom were the Medici Family.

The situation in Florence was uniquely favourable to the arts. The civic pride of Florentines found expression in statues of the patron saints commissioned from Ghiberti and Donatello for niches in the grain-market guildhall known as Or San Michele, and in the largest dome built since antiquity, placed by Brunelleschi on the Florence cathedral. The cost of construction and decoration of palaces, churches, and monasteries was underwritten by wealthy merchant families, chief among whom were the Medici Family. The Medici traded in all of the major cities in Europe, and one of the most famous masterpieces of Northern Renaissance art, The Portinari Altarpiece, by Hugo van der Goes (c. 1476; Uffizi, Florence), was commissioned by their agent, Tommaso Portinari. Instead of being painted with the customary tempera of the period, the work is painted with translucent oil glazes that produce brilliant jewel-like colour and a glossy surface. Early Northern Renaissance painters were more concerned with the detailed reproduction of objects and their symbolic meaning than with the study of scientific perspective and anatomy even after these achievements became widely known. On the other hand, central Italian painters began to adopt the oil medium soon after The Portinari Altarpiece was brought to Florence in 1476.

The Medici traded in all of the major cities in Europe, and one of the most famous masterpieces of Northern Renaissance art, The Portinari Altarpiece, by Hugo van der Goes (c. 1476; Uffizi, Florence), was commissioned by their agent, Tommaso Portinari. Instead of being painted with the customary tempera of the period, the work is painted with translucent oil glazes that produce brilliant jewel-like colour and a glossy surface. Early Northern Renaissance painters were more concerned with the detailed reproduction of objects and their symbolic meaning than with the study of scientific perspective and anatomy even after these achievements became widely known. On the other hand, central Italian painters began to adopt the oil medium soon after The Portinari Altarpiece was brought to Florence in 1476.High Renaissance art, which flourished for about 35 years, from the early 1490s to 1527, when Rome was sacked by imperial troops, revolved around three towering figures: Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Michelangelo (1475–1564), and Raphael (1483–1520). Each of the three embodied an important aspect of the period: Leonardo was the ultimate Renaissance man, a solitary genius to whom no branch of study was foreign; Michelangelo emanated creative power, conceiving vast projects that drew for inspiration on the human body as the ultimate vehicle for emotional expression; Raphael created works that perfectly expressed the classical spirit—harmonious, beautiful, and serene.

Although Leonardo was recognized in his own time as a great artist, his restless researches into anatomy, the nature of flight, and the structure of plant and animal life left him little time to paint. His fame rests on a few completed works; among them are the “Mona Lisa” (1503–05, Louvre), “The Virgin of the Rocks” (c. 1485, Louvre), and the sadly deteriorated fresco “The Last Supper” (1495–98, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan).

Although Leonardo was recognized in his own time as a great artist, his restless researches into anatomy, the nature of flight, and the structure of plant and animal life left him little time to paint. His fame rests on a few completed works; among them are the “Mona Lisa” (1503–05, Louvre), “The Virgin of the Rocks” (c. 1485, Louvre), and the sadly deteriorated fresco “The Last Supper” (1495–98, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan). Michelangelo's early sculpture, such as the “Pietà” (1499, St. Peter's, Rome) and the “David” (1501–04, Accademia, Florence), reveals a breathtaking technical ability in concert with a disposition to bend rules of anatomy and proportion in the service of greater expressive power. Although Michelangelo thought of himself first as a sculptor, his best known work is the giant ceiling fresco of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, Rome. It was completed in four years, from 1508 to 1512, and presents an incredibly complex but philosophically unified composition that fuses traditional Christian theology with Neoplatonic thought.

Michelangelo's early sculpture, such as the “Pietà” (1499, St. Peter's, Rome) and the “David” (1501–04, Accademia, Florence), reveals a breathtaking technical ability in concert with a disposition to bend rules of anatomy and proportion in the service of greater expressive power. Although Michelangelo thought of himself first as a sculptor, his best known work is the giant ceiling fresco of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, Rome. It was completed in four years, from 1508 to 1512, and presents an incredibly complex but philosophically unified composition that fuses traditional Christian theology with Neoplatonic thought. Raphael's greatest work, “The School of Athens” (1508–11), was painted in the Vatican at the same time that Michelangelo was working on the Sistine Chapel. In this large fresco Raphael brought together representatives of the Aristotelian and Platonic schools of thought. Instead of the densely packed, turbulent surface of Michelangelo's masterpiece, Raphael placed his groups of calmly conversing philosophers and artists in a vast court with vaults receding into the distance. Raphael was initially influenced by Leonardo, and he incorporated the pyramidal composition and beautifully modelled faces of “The Virgin of the Rocks” into many of his own paintings of the Madonna. He differed from Leonardo, however, in his prodigious output, his even temperament, and his preference for classical harmony and clarity.

Raphael's greatest work, “The School of Athens” (1508–11), was painted in the Vatican at the same time that Michelangelo was working on the Sistine Chapel. In this large fresco Raphael brought together representatives of the Aristotelian and Platonic schools of thought. Instead of the densely packed, turbulent surface of Michelangelo's masterpiece, Raphael placed his groups of calmly conversing philosophers and artists in a vast court with vaults receding into the distance. Raphael was initially influenced by Leonardo, and he incorporated the pyramidal composition and beautifully modelled faces of “The Virgin of the Rocks” into many of his own paintings of the Madonna. He differed from Leonardo, however, in his prodigious output, his even temperament, and his preference for classical harmony and clarity.The creator of High Renaissance architecture was Donato Bramante (Bramante, Donato) (1444–1514), who came to Rome in 1499, when he was 55. His first Roman masterpiece, the Tempietto (1502) at S. Pietro in Montorio, is a centralized dome structure that recalls classical temple architecture. Pope Julius II (reigned 1503–13) chose Bramante to be papal architect, and together they devised a plan to replace the 4th-century Old St. Peter's with a new church of gigantic dimensions. The project was not completed, however, until long after Bramante's death.

Humanistic studies continued under the powerful popes of the High Renaissance, Julius II and Leo X, as did the development of polyphonic music. The Sistine Choir, which performed at services when the pope officiated, drew musicians and singers from all of Italy and northern Europe. Among the most famous composers who became members were Josquin des Prez (1445–1521) and Palestrina (1525–84).

The Renaissance as a unified historical period ended with the fall of Rome in 1527. The strains between Christian faith and classical humanism led to Mannerism in the latter part of the 16th century. Great works of art animated by the Renaissance spirit, however, continued to be made in northern Italy and in northern Europe.

Seemingly unaffected by the Mannerist crisis, northern Italian painters such as Correggio (1494–1534) and Titian (1488/90–1576) continued to celebrate both Venus and the Virgin Mary without apparent conflict. The oil medium, introduced to northern Italy by Antonello da Messina and quickly adopted by Venetian painters who could not use fresco because of the damp climate, seemed particularly adapted to the sanguine, pleasure-loving culture of Venice. A succession of brilliant painters—Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese—developed the lyrical Venetian painting style that combined pagan subject matter, sensuous handling of colour and paint surface, and a love of extravagant settings. Closer in spirit to the more intellectual Florentines of the Quattrocento was the German painter Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who experimented with optics, studied nature assiduously, and disseminated his powerful synthesis of Renaissance and Northern Gothic styles through the Western world by means of his engravings and woodcuts.

Seemingly unaffected by the Mannerist crisis, northern Italian painters such as Correggio (1494–1534) and Titian (1488/90–1576) continued to celebrate both Venus and the Virgin Mary without apparent conflict. The oil medium, introduced to northern Italy by Antonello da Messina and quickly adopted by Venetian painters who could not use fresco because of the damp climate, seemed particularly adapted to the sanguine, pleasure-loving culture of Venice. A succession of brilliant painters—Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese—developed the lyrical Venetian painting style that combined pagan subject matter, sensuous handling of colour and paint surface, and a love of extravagant settings. Closer in spirit to the more intellectual Florentines of the Quattrocento was the German painter Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who experimented with optics, studied nature assiduously, and disseminated his powerful synthesis of Renaissance and Northern Gothic styles through the Western world by means of his engravings and woodcuts.- Andreas Vesalius

- Andreas Vokos Miaoulis

- Andre, Carl

- Andre Dubus

- Andrei Liapchev

- Andreina Pagnani

- Andreini, Francesco

- Andreini, Giovambattista

- Andreini, Isabella

- Andrei Okounkov

- Andrei Romanovich Chikatilo

- Andreis, Felix de

- Andrej Hlinka

- Andre Norton

- Andreotti, Giulio

- and Reproduction Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender

- Andres Bonifacio

- Andres Serrano

- Andretti, Mario

- Andrew, Baron Lloyd-Webber of Sydmonton Lloyd Webber

- Andrew Baxter

- Andrew Bell

- Andrew Boorde

- Andrew Browne Cunningham

- Andrew Carnegie