Belarus

Introduction

also spelled Byelarus, formerly Belorussia, or Byelorussia, officially Republic of Belarus, Belarusian Respublika Byelarusʾ, also called White Russia,

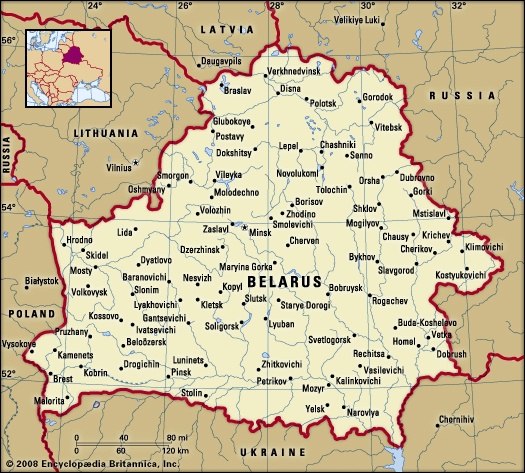

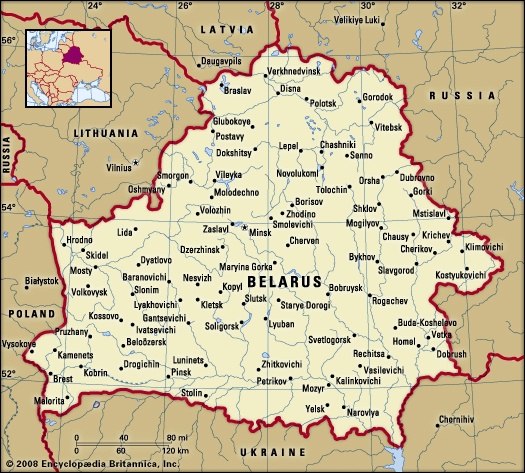

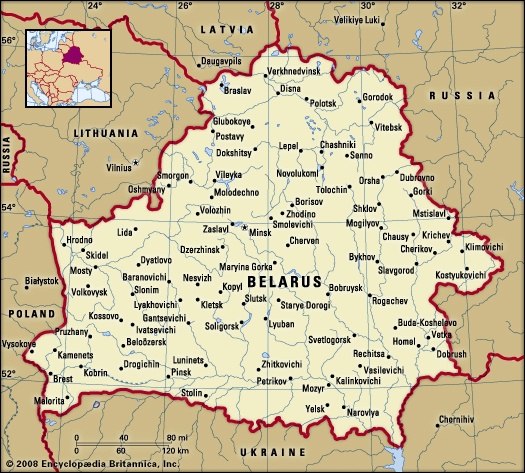

Belarus, flag of country of eastern Europe. Until it became independent in 1991, it was the smallest of the three Slavic republics that formed part of the Soviet Union. On the northwest Belarus adjoins Latvia and Lithuania, while Russia lies to the northeast and east, Ukraine to the south, and Poland to the west. The capital is Minsk.

country of eastern Europe. Until it became independent in 1991, it was the smallest of the three Slavic republics that formed part of the Soviet Union. On the northwest Belarus adjoins Latvia and Lithuania, while Russia lies to the northeast and east, Ukraine to the south, and Poland to the west. The capital is Minsk.

country of eastern Europe. Until it became independent in 1991, it was the smallest of the three Slavic republics that formed part of the Soviet Union. On the northwest Belarus adjoins Latvia and Lithuania, while Russia lies to the northeast and east, Ukraine to the south, and Poland to the west. The capital is Minsk.

country of eastern Europe. Until it became independent in 1991, it was the smallest of the three Slavic republics that formed part of the Soviet Union. On the northwest Belarus adjoins Latvia and Lithuania, while Russia lies to the northeast and east, Ukraine to the south, and Poland to the west. The capital is Minsk.While Belarusians share a distinct ethnic identity and language, they never previously enjoyed unity and political sovereignty. Belarusian history is thus less an isolable national narrative than a study of regional forces, their interplay, and their effects on the Belarusian people. The territory that is now Belarus underwent partition and changed hands repeatedly; as a result, much of the history of Belarus is inseparable from that of its neighbours.

The land (Belarus)

Relief

The topography of Belarus was largely shaped by glaciation during the Pleistocene Epoch (1,600,000 to 10,000 years ago). Much of the country consists of flat lowlands separated by low, level-topped hills and uplands. The highest point, Dzyarzhynsk Mountain, is only 1,135 feet (345 metres) above sea level, and more than half the surface area of Belarus lies below 660 feet. The higher areas are formed by ridges of glacial morainic material dating from the Valday glaciation, the last advance of Pleistocene ice in eastern Europe. The largest of the ridges, the Belarusian Ridge, extends northeastward from the Polish border on the southwest to north of Minsk, where it widens into the Minsk Upland before turning eastward to link up with the Smolensk-Moscow Upland. Running transverse to the main Belarusian Ridge, the Ashmyany Upland, consisting of terminal moraines from the same glacial period, lies between Minsk and Vilnius in neighbouring Lithuania. The surfaces of its ridges tend to be flat or gently rolling and covered by light, sandy podzolic soils; they are largely cleared of their original forest cover.

The topography of Belarus was largely shaped by glaciation during the Pleistocene Epoch (1,600,000 to 10,000 years ago). Much of the country consists of flat lowlands separated by low, level-topped hills and uplands. The highest point, Dzyarzhynsk Mountain, is only 1,135 feet (345 metres) above sea level, and more than half the surface area of Belarus lies below 660 feet. The higher areas are formed by ridges of glacial morainic material dating from the Valday glaciation, the last advance of Pleistocene ice in eastern Europe. The largest of the ridges, the Belarusian Ridge, extends northeastward from the Polish border on the southwest to north of Minsk, where it widens into the Minsk Upland before turning eastward to link up with the Smolensk-Moscow Upland. Running transverse to the main Belarusian Ridge, the Ashmyany Upland, consisting of terminal moraines from the same glacial period, lies between Minsk and Vilnius in neighbouring Lithuania. The surfaces of its ridges tend to be flat or gently rolling and covered by light, sandy podzolic soils; they are largely cleared of their original forest cover.Separated by the morainic ridges lie wide lowlands, which are mostly poorly drained and marshy and contain many small lakes. To the north of the main line of morainic hills are two broad plains; the north of the republic comprises the Polatsk Lowland, and the northwestern corner, near Hrodna, the Nyoman Lowland. South of the Belarusian Ridge the wide and very flat Central Byarezina Plain gently slopes southward to merge imperceptibly with the even more extensive Pripet Marshes (Belarusian: Palyessye, “Woodlands”). A waterlogged area in the basin of the Pripet (Prypyats') River, a main tributary of the Dnieper (Dnyapro), the Pripet Marshes extend southward into Ukraine and occupy a structural trough. The trough is filled with outwash sands and gravels deposited by the meltwaters of the last Pleistocene glaciation. The minimal variation in relief makes the Pripet Marshes the largest area of swamp in Europe.

Drainage and soils

Belarus has about 20,800 streams, with a total length of about 56,300 miles (90,600 kilometres), and some 10,800 lakes. The greater part of the republic lies in the basin of the Dnieper (Dnieper River), which flows across Belarus from north to south on its way to the Black Sea, and of its major tributaries, the Byarezina and Pripet on the right bank and the Sozh on the left. In the north the Polatsk Lowland is drained by the Western Dvina (Dzvina) River to the Baltic Sea, to which also flows the Neman (Nyoman) in the west. The extreme southwest corner of Belarus is drained by the Mukhavyets, a tributary of the Bug (Buh) River, which forms part of the border with Poland and flows to the Baltic Sea. The Mukhavyets and Pripet are linked by a ship canal, thereby connecting the Baltic and Black seas. The rivers are generally frozen from December to late March, after which occur about two months of maximum flow. The largest lakes are Narach, Asvyeyskaye, and Drysvyaty.

About three-fifths of Belarus is covered by podzolic soils. On the uplands these soils are mainly clay loams developed on loess subsoils, which can be productive with the use of fertilizers. The plains and lowlands have mostly sandy podzols of low fertility interspersed with swampy clays, which have a high humus content and can be very fertile when drained.

Climate

Belarus has a cool continental climate moderated by maritime influences from the Atlantic Ocean. Average January temperatures range from 25° F (−4° C) in the southwest to 18° F (−8° C) in the northeast, but thaw days are frequent; correspondingly, the frost-free period decreases from more than 170 days in the southwest to 130 in the northeast. Maximum temperatures in July are about 63° to 66° F (17° to 19° C). Rainfall is moderate, though higher than over most of the East European Plain, and ranges from 21 inches (533 millimetres) on the lowlands to 28 inches on the higher morainic ridges. Maximum rainfall occurs from June to August.

Plant and animal life

The natural vegetation of the country is mixed deciduous and coniferous forest. In the north, conifers, notably pine and spruce, tend to predominate; southward the proportion of deciduous trees, such as oak and hornbeam, increases. Silver birch is common everywhere, especially as the first colonist on burned or disturbed areas. Over the centuries, the clearing of forest land for agricultural use has removed the greater part of the primeval forest, especially the deciduous trees, which prefer richer soils. In particular, the forest of the uplands had largely been removed by the late 16th century.

The Belovezhskaya (Polish: Białowieża) Forest (Belovezhskaya Forest), on the western border with Poland (into which it extends), is the largest surviving area of primeval mixed forest in Europe, encompassing more than 460 square miles (1,200 square kilometres). Preserved for centuries as the private hunting forest of first the Polish kings and later the Russian tsars, it was made a nature reserve (and later a national park) on both sides of the frontier. The rich forest vegetation that once covered much of Europe survives here, dominated by trees that have grown to exceptional heights. The forest is the major home of the European bison, or wisent, which had become extinct in the wild following World War I but was reintroduced using zoo animals. Elk, deer, and boar also are found there and in other forests of Belarus, together with small game, hare, squirrels, foxes, badgers, marten, and, along the rivers, beaver. Birds include grouse, partridge, woodcock, snipe, and duck, and many of the rivers are well stocked with fish.

Environment

The accident at the Chernobyl (Chernobyl accident) nuclear power plant in Ukraine in April 1986 resulted in a number of immediate and long-term consequences for the environment of Belarus, which bore the brunt of the radioactive fallout that resulted. About one-fourth of its surface area was affected. In addition to the radiation-tainted land, water, plants, and livestock, the human medical and psychological costs of the accident included an increase in birth defects and cancer (particularly of the thyroid) and a declining birth rate, at least partly in response to fears of those defects.

Settlement patterns

The population density of Belarus is relatively low. Much of the country, particularly the Pripet Marshes, is sparsely populated, the greatest concentrations being in the central uplands and the southwest. During the period of Soviet rule, the process of industrial growth steadily increased the urban proportion of the population, from only one-fifth at the end of World War II to more than two-thirds by the 1990s. Correspondingly, the number of urban places (including settlements of town type) more than doubled. Chief among the more than a dozen cities with populations greater than 100,000 is the rapidly growing capital, Minsk. Most of the increase in urban population has resulted from migration from rural areas, leaving many declining or moribund villages.

The people

Ethnic Belarusians (Belarus) make up more than three-fourths of the country's population. Russians, many of whom migrated to the Belorussian S.S.R. in the 1960s, '70s, and '80s, form the second largest ethnic group. Most of the remainder of the population are Poles and Ukrainians, with a small number of Latvians, Lithuanians, and Tatars. Before World War II, however, Jews constituted the second largest group in the republic (and more than half the urban population); the genocide of European Jewry and postwar emigration nearly eliminated Jews from the republic. Both Belarusian (Belarusian language) and Russian are official languages. Belarusian, which is central to the concept of national identity, is an East Slavic language that is related to both Russian and Ukrainian, with dialects that are transitional to both. It is written in a Cyrillic alphabet and has loanwords from both Polish and Russian, which is reflective of the region's history. An older form of Belarusian was the official language of the grand duchy of Lithuania, of which present-day Belarus was an important component. Most Belarusians who profess a religion adhere to Eastern Orthodoxy. There is, however, a sizable minority of Roman Catholics, and the Eastern-rite (Uniate) church is experiencing something of a revival after centuries of persecution under tsarist Russia and the Soviet government.

After World War II Belarus exhibited a fairly high birth rate, largely as the result of a postwar baby boom. A steep decline followed in the 1960s, and thereafter a more gradual decline ensued. At the same time, life expectancy slowly decreased. As a result, the natural growth of the population slowed and then declined by the mid-1990s, as did the overall increase in population (notwithstanding a net in-migration balance). Moreover, fertility rates also fell.

The economy

Devastation during World War II nearly wiped out agriculture and industry in the Belorussian S.S.R., and the intensive postwar drive to restore the economy resulted in a large industrial sector that depended on the other Soviet republics, particularly Russia (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), for energy and raw materials. The dissolution of the Soviet Union not only dramatically increased the cost of those raw materials but also reduced the traditional market for Belarusian manufactured goods. As a result, production decreased in Belarus during the early 1990s. Moreover, the movement toward a market economy in Belarus was slower than that of other former Soviet republics, with only a small percentage of state-run industry and agriculture privatized in the years following independence. Largely in response to this economic upheaval, Belarus sought closer economic ties with Russia.

Resources

The republic is generally poorly endowed with mineral resources. The government is attempting to accelerate the development of its raw-material base, but Belarus remains dependent on Russia for most of its energy and fossil-fuel requirements. In the 1960s, petroleum was discovered in the southeastern part of the republic, near Rechytsa. Production, which peaked in 1975, had fallen to one-fourth of that total by the 1990s, when it stabilized.

Belarus does possess, however, one of the world's largest reserves of potash (potassium salts)—discovered in 1949 south of Minsk and exploited from the 1960s around the new mining town and fertilizer-manufacturing centre of Salihorsk. Although exports of potash to other former Soviet republics declined significantly in the 1990s, exports to other countries remained at a high level. The country also is a world leader in the production of peat, which is especially abundant in the Pripet Marshes. In briquette form it is used as fuel. Among the other minerals recovered are salt, an important deposit of which, near Mazyr, was opened in the 1980s; building materials, chiefly limestone and, near Hrodna, quartz sands for glassmaking, both used locally; and small deposits of gold and diamonds.

Industry

Military production was of high industrial priority during the Soviet era, and the transition to primarily civilian production was difficult. Nevertheless, mining and manufacturing remain the major component of the Belarusian economy and account for roughly half the gross domestic product (GDP), with the processing of minerals and hydrocarbons playing an important role. A large facility for producing potash fertilizers is located at Salihorsk. There are oil refineries in the Polatsk area and at Mazyr in the south. Both are served by branches of a major pipeline originating in western Siberia, but the facilities at Mazyr also process local oil from Rechytsa. There also is a large petrochemical plant at Polatsk that produces polyolefins. At Hrodna nitrogenous fertilizers are made using natural gas piped from Dashava in Ukraine.

Heavy industry is less developed in Belarus. There is some engineering, concentrated chiefly in Minsk, where heavy-duty trucks and tractors are manufactured, and in its satellite town, Zhodzina, which produces large-capacity dump trucks. Dump trucks are also made in Mahilyow. Other engineering products include machine tools, such as metal-cutting equipment. Precision manufacturing was developed during the 1970s and '80s, notably of such consumer goods as radios and television sets, watches, bicycles, and computers. Other industries are small-scale, and products are mostly for local consumption. They include timber processing, furniture making, match and paper making, textile and clothing manufacture, and food processing.

Agriculture

The agricultural sector in Belarus (which employs about one-fifth of the labour force but constitutes a diminishing proportion of the GDP) is dominated by large state and collective farms. Private holdings were permitted for household use during the Soviet era, but while their number increased dramatically following independence they remained small in size. Most of Belarus has soils of only moderate fertility, but the better-drained uplands can be productive with fertilizer application. Most of the country has mixed crop and livestock farming, with a strong emphasis on flax growing. (During the late Soviet era the Belorussian S.S.R. produced about one-fourth of the U.S.S.R. total.) Grain, chiefly barley, rye, and oats, and potatoes are the other main field crops, of which a large percentage is used for animal feed. Cattle and pig raising are also important. Considerable areas of the swampy lowlands have been drained since the late 19th century, with much of the reclaimed land being used for fodder crops. Dairying and truck farming are locally important in the vicinity of Minsk. Nearly one-third of Belarus is covered by forests, which are exploited for the production of wood and paper products.

The agricultural sector in Belarus (which employs about one-fifth of the labour force but constitutes a diminishing proportion of the GDP) is dominated by large state and collective farms. Private holdings were permitted for household use during the Soviet era, but while their number increased dramatically following independence they remained small in size. Most of Belarus has soils of only moderate fertility, but the better-drained uplands can be productive with fertilizer application. Most of the country has mixed crop and livestock farming, with a strong emphasis on flax growing. (During the late Soviet era the Belorussian S.S.R. produced about one-fourth of the U.S.S.R. total.) Grain, chiefly barley, rye, and oats, and potatoes are the other main field crops, of which a large percentage is used for animal feed. Cattle and pig raising are also important. Considerable areas of the swampy lowlands have been drained since the late 19th century, with much of the reclaimed land being used for fodder crops. Dairying and truck farming are locally important in the vicinity of Minsk. Nearly one-third of Belarus is covered by forests, which are exploited for the production of wood and paper products.Finance

Independent Belarus restructured its Soviet-style banking system into a two-tier system consisting of the National Bank of Belarus and a growing number of commercial banks, most of which are either joint-stock or limited-liability companies. The republic introduced its own currency, the Belarusian rubel, in 1992. A securities market and stock exchange were also established that year.

Trade

During much of the Soviet period, the republic was a net exporter, with the bulk of its trade conducted with other Soviet republics, principally Russia and Ukraine. Independent Belarus became a net importer, however, when the price of previously inexpensive raw materials and energy from Soviet sources rose to meet world market levels. Nonetheless, Russia, Poland, and Ukraine remain the republic's main trading partners, with trade increasing with Germany. Chief exports include trucks, tractors, refrigerators, television sets, energy products, fertilizer, and meat and dairy products. Major imports include petroleum, natural gas, rolled metal, rubber, paint, and consumer goods.

Energy

Nearly all electricity is generated at thermal power stations using piped oil and natural gas; however, there is some local use of peat, and there are a number of low-capacity hydroelectric power plants.

Transportation

Belarus has a good railway network, headed by major interregional railways that crisscross the country: east-west between Berlin, Warsaw, and Moscow; north-south between St. Petersburg and Kiev (Ukraine); and northwest-southeast between the Baltic countries and Ukraine. There is an east-west trunk road through Minsk, but other roads are poor. Rivers and the Dnieper-Bug Canal also serve as transportation routes. Minsk has good air connections, including international flights.

Administration and social conditions

Government

A new constitution entered into force in Belarus in March 1994. Characterizing the republic as a “democratic, social state,” that document guaranteed a broad range of rights and freedoms and pledged the state to create the conditions for full employment. It was based on the separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers. Under the 1994 constitution, deputies were elected by universal adult suffrage to five-year terms to the government's highest legislative body, the Supreme Soviet, which confirmed the budget, called for national elections and referenda, and was responsible for domestic, foreign, and military policy. Following the passage of a referendum (of questionable legitimacy) in November 1996, however, the constitution was revised to greatly expand the powers of the president, Alyaksandr Lukashenka (Lukashenka, Alyaksandr Hrygorevich) (Lukashenko), while greatly diminishing those of a reconstituted parliament.

There are three tiers of local government: the largest consists of six voblastsi (provinces) and one municipality (horad); they in turn are divided into rayony (sectors) and cities, with some larger cities further divided into rayony. Towns, villages, and settlements constitute the final tier.

The judicial system comprises the Supreme Court and its lower courts, the Supreme Economic Court and its lower courts, and the Constitutional Court, whose 11 judges (elected by the Supreme Soviet) have the final ruling on the republic's basic law.

Political parties

Long a monolithic ruling party, the Communist Party was banned in 1991 following the demise of the Soviet Union. It regrouped as the Party of Communists before reemerging under the name Communist Party of Belarus after the lifting of the ban in 1993. The Agrarian Party represents the interests of collective and state farms, while a variety of parties represent social democratic, liberal, market-oriented, and ecologically concerned constituencies. The Belarusian Popular Front has been at the forefront of the nationalist movement since its founding in 1989 but has had little electoral success.

Education

Under the former Soviet government the republic achieved universal literacy. Education is compulsory from ages 7 to 16. Institutions of higher learning include the Belarusian State University, the Homyel State University, the Hrodna State University, the Belarusian Agricultural Academy in Horki, and medical, pedagogical, technological, and agricultural institutes. The Belarusian Academy of Sciences maintains a nuclear reactor.

Health and welfare

Health care improved in the republic after World War II, and the capacity of medical facilities increased. Nevertheless, inadequate training and technology contributed to a system that has failed to meet many basic medical needs in independent Belarus.

Cultural life

Little survives in Belarus of the earliest period of settlement by eastern Slavs; a distinctively Belarusian culture began to emerge clearly only in the 16th century. In the later tsarist period, considerable efforts were made to suppress the Belarusian language and culture. Long periods of foreign control, first by the grand duchy of Lithuania and the kingdom of Poland, then by tsarist Russia and later by the Soviet Union, brought a series of outside influences, from the European Baroque and classical architectural styles to the cultural constraints of Socialist Realism.

Architecture

One of the oldest surviving monuments of architecture in the country is the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Polatsk, dating from the 11th century and built in the Eastern Orthodox style. The church of Barys and Hlyeb in Hrodna dates from the 12th century. Most of the other early buildings that remain, mostly as ruins, are the princely stone fortresses of the 12th to 16th century. One of the best-known of these is the 13th-century White Tower in Kamyanyets.

The 17th century marked the appearance of the Baroque style, which was largely linked to the eastward movement of Roman Catholicism; it is exemplified by the design of the Jesuit, Bernardine, and Bridgettine churches in Hrodna. Belarusian craftsmen played a role in extending Baroque influence farther eastward into Russia, where it was adapted as the “Moscow Baroque” style. By the 18th century, classical styles predominated in Belarus, as seen in the Governor's Palace in Hrodna. The ravages of World War II destroyed a large segment of the country's architectural heritage, especially in Minsk. Because much of Minsk was reconstructed after the war, most of the architecture of the city centre reflects the grandiose Stalinist style with its classical borrowings.

Literature

Literary activity in Belarus dates to the 11th century. In the 12th century St. Cyril of Turaw, venerated among Orthodox Slavs as “the second St. Chrysostom,” wrote sermons and hymns. In the 16th century Frantsysk Skaryna of Polatsk translated the Bible into Belarusian and wrote extensive explanatory introductions to each book. His editions, produced in Prague (1517–19) and Vilnius (1522–25), were the first printed books not only in Belarus but in the whole of eastern Europe. In the 17th century the Belarusian poet Symon Polatski (Symeon of Polatsk) was the first to bring Baroque literary style to Moscow.

Modern Belarusian literature began in the first half of the 19th century with the work of Yan Chachot and Vincent Dunin-Martsinkyevich, who translated part of the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz's epic Master Thaddeus into Belarusian. Literary classics of the early 20th century include works by the poets Maksim Bahdanovich, Ales Harun, Vladimir Zylka, Kazimir Svayak, Yanka Kupala, and Yakub Kolas and the prose writers Zmitrok Byadulya and Maksim Haretski. Many of these writers had been contributors to the influential Belarusian newspaper Nasha Niva (“Our Cornfield”), published in Vilnius during the period 1906–16. Of crucial importance for an understanding of the Belarusian cultural predicament in the face of war and revolution are Kupala's play The Locals (1922) and Haretski's short novel Two Souls (1919).

Many outstanding poets and prose writers made their mark in the 1920s, including the poets Vladimir Dubovka and Yazep Pushcha, the novelist Kuzma Chorny, and the satirist and playwright Kandrat Krapiva. Pushcha's literary polemics with the second-rate poet Andrey Aleksandrovich at the end of the 1920s marked the beginning of political control over Belarusian cultural matters. Literature in the part of Belarus that was under Polish control until 1939 developed somewhat more freely. Two writers of note emerged from that area, Maksim Tank, author of the long poems Narach (1937) and Kalinowski (1938), and Natalla Arseneva, whose greatest poems are to be found in the collections Beneath the Blue Sky (1927), Golden Autumn (1937), and Today (1944). Other writers who stayed during the occupation and then went into exile are the poets Chvedar Illasyevich, Matvey Syadnov, and Larysa Genius.

Most noteworthy of the writers to preserve and develop the Belarusian literary tradition in the 1940s and '50s are the poets Pimen Panchanka and Arkadi Kulyashov and the prose writers Yanka Bryl, Ivan Shamyakin, and Ivan Melezh. The 1960s marked the tentative beginnings of yet another national revival with the novels of Vasil Bykov and Uladzimir Karatkievich. Among younger writers, the poets Yawhyeniya Yanishchyts and Ales Razanov and the short-story writer Anatol Sys should be noted.

Music

Belarus has long had its own folk music, which was encouraged during the Soviet period and performed by a number of companies. There was also a considerable tradition of church music from the 16th century on. The development of classical music largely has been a feature of the period since World War II. Among the most notable composers has been Kulikovich Shchahlow, who like some of the writers went into exile after the war. Others include Yawhen Hlyebaw, composer of the opera Your Spring (1963) and the ballet Alpine Ballad (1967), and Yawhen Tsikotski, whose works include the operas Mikhas Padhorny (1939–57) and Alesya (1944). There is a conservatory of music in Minsk and a national philharmonic society.

History

The Belarusian region has a long history of human settlement. Archaeology has provided evidence of Upper Paleolithic cultures, and Neolithic (New Stone Age) remains are widespread. The area was one of the earliest to be inhabited by Slavs, who settled there between the 6th and the 8th centuries AD. The early Slavic tribes—the Dregovichi, Radimichi, Krivichi, and Drevlyane—had formed local principalities, such as those of Pinsk, Turaw (Russian: Turov), Polatsk (Polotsk), Slutsk, and Minsk, by the 8th to 9th century. These all came under the general suzerainty of Kievan Rus, the first East Slavic state, beginning in the mid-9th century. The regional economy was based on primitive, shifting agriculture on burned-over forestland, as well as on honey collecting and fur hunting. Trade developed along the rivers, particularly on the Dnieper, which from about 930 was part of the “water road” from Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire, via Kiev and Novgorod, to the Baltic Sea. Trading settlements multiplied, and many of the towns of present-day Belarus were founded by the end of the 12th century. Two of the earliest-mentioned towns of Slavic foundation, Polatsk and Turaw, first appear in historical documents in the years 862 and 980, respectively. Brest (formerly Brest-Litovsk) is first recorded in 1017 and Minsk in 1067.

Lithuanian and Polish rule

The overthrow of Kiev by the Mongol invasion of 1240 brought about the dissolution of Kievan Rus. Many Belarusian towns were laid waste and became dependencies of the empire of the Golden Horde. Over the next 150 years the grand duchy of Lithuania (Lithuania, grand duchy of) expanded, absorbing much of the Belarusian population. Under Lithuanian rule, however, the conquered regions retained a large degree of autonomy. Throughout the 13th and 14th centuries the Lithuanian state grew, encompassing the city of Smolensk and the lands eastward to the neighbourhood of Moscow and southward to Kiev and the shores of the Black Sea. During this epoch of Lithuanian domination, the Belarusian language and nationality began to take shape.

A personal union between the Lithuanian and Polish ruling houses commenced under the Jagiellon dynasty in 1386, when the Lithuanian grand duke Jogaila (Polish: Władisław II Jagiełło) married Queen Jadwiga of Poland. Roman Catholicism became the official religion of the grand duchy of Lithuania, but the peasantry remained overwhelmingly Orthodox. Between the Polish-Lithuanian realm and the rising power of Muscovy there developed an incessant and bitter struggle for land and influence. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Smolensk and Lithuania's easternmost lands were lost to Russia, although the Belarusian population remained largely under Lithuanian control. Three sets of laws, known as the Lithuanian Statutes, codified civil and property rights in Lithuanian-controlled lands in the 16th century. In 1557 a far-reaching agrarian reform plan was instituted, introducing the three-field crop rotation system of agriculture and changing the obligations of peasants to landowners. The system, initially imposed on crown estates, was rapidly adopted on the properties of the nobility; it remained in operation with little modification until the 20th century. The combined effects of the changes reduced the peasants, who previously had retained at least some freedom to migrate, to full serfdom.

The Union of Lublin (Lublin, Union of) (1569) made Poland and Lithuania a single, federated state. Although Lithuania retained the title of grand duchy and its code of laws, its western province Podlasia, which had been heavily settled by Polish colonists, was ceded to Poland, as were the steppe lands and Kiev. Among the Belarusian population a mainly Polish-speaking Roman Catholic aristocracy developed, but the peasantry on the whole remained Orthodox. In 1596 the Union of Brest-Litovsk (Brest-Litovsk, Union of) signaled an attempt to unify the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches in the Polish-Lithuanian state, combining acknowledgment of papal supremacy with the Orthodox rites and traditions. The new Eastern-rite church made some limited headway, particularly among Belarusians and Ukrainians, but it constantly came under pressure from tsarist and later Soviet authorities, resulting in the conversion of some of its membership to Orthodoxy. The rule of the Polish landowners was often heavy and unpopular, and many Belarusians (especially those opposed to joining the Eastern-rite church) fled to the steppe lands that were home to the Cossacks. Large-scale Cossack-led revolts occurred in 1648–54, but the Belarusian lands remained under Poland until the reign of Catherine II (the Great) of Russia (1762–96). Economic development was slow, especially in the extensive Pripet Marshes. The Belarusian population was almost entirely engaged in agriculture, while trade lay in the hands of Poles and Jews.

Russian rule

By way of the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Catherine the Great acquired the eastern portion of present-day Belarus, including the towns of Vitsyebsk (Russian: Vitebsk), Mahilyow (Mogilyov), and Homyel (Gomel). The Second Partition (1793) gave Russia Minsk and the central region, and in 1795 the Third Partition incorporated the remainder into the Russian Empire.

Under Russian rule the area was divided administratively into the governorships (provinces) of Grodno (Belarusian: Hrodna), Minsk, Mogilyov, Vilnia (now Vilnius, Lithuania), and Vitebsk, and, until the formation of the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1919, Belarusian history was largely tied to the course of events in the Russian Empire and revolutionary Russia. Napoleon crossed the region in his advance on Moscow in 1812 and again during his retreat. One of the heaviest battles of Napoleon's Russian campaign took place as French troops retreated across the Byarezina (Berezina) River.

In the 19th century small-scale industries largely based on local supplies began to grow in Belarusian towns. Among them were timber working, glassmaking, and, along the rivers, boatbuilding. Following the emancipation of the serfs in the 1860s, the tempo of industrialization increased somewhat, particularly with the coming of the railways beginning in the 1880s. Nevertheless, the generally poor economic conditions resulted in considerable emigration, especially from rural areas. In the 50 years before the Russian Revolution of 1917, nearly 1.5 million people left the provinces within which present-day Belarus is located. Most of the emigrants went to the United States or Siberia, with more than 600,000 emigrating to the latter between 1896 and 1915.

The first attempt to establish a Marxist party in Russia took place in Minsk in 1898 when a small congress laid the foundation for the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. During World War I, heavy fighting between German troops and those of the Russian Empire took place in the province with considerable destruction. Following the Russian Revolution, in which a provisional government replaced the collapsed Russian monarchy only to be itself overthrown by Bolshevik revolutionaries, the new Soviet government of Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (Brest-Litovsk, treaties of) with Germany and its allies on March 3, 1918. Under the terms of this short-lived treaty, Russia gave up part of present-day Belarus, along with Ukrainian and Baltic lands, to Germany. With Germany's subsequent defeat by Russia's Western allies, the terms of Brest-Litovsk were abrogated.

The emergence of the Belorussian S.S.R.

Belarusian nationalist and revolutionary stirrings had been evident at least since the Russian Revolution of 1905, when peasants joined the uprising against the monarchy. The creation of a Belarusian state began in 1918 and proceeded with fits and starts amid the turmoil of World War I, the Russian Revolution of l917, and the ensuing civil war (1918–20). In 1918, while most of the region was occupied by the German army, an independent Belarusian Democratic Republic was declared. With the withdrawal of German troops after the war, however, the Bolsheviks announced the formation of the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic on January 1, 1919. The republic's territorial integrity was quickly breached; beginning in April of that year, troops of newly reconstituted Poland advanced eastward to the Byarezina River only to be thrown back again in 1920. Hostilities between Russia and Poland ended with the Treaty of Riga (signed March 18, 1921), which divided the area of Belarus between Poland and Soviet Russia along the lines of the First Partition of Poland. The Belorussian S.S.R. did grow to the east in 1924 when Russia transferred to the Belorussian S.S.R. the regions of Polotsk, Vitebsk, Orsha, and Mogilyov, which had large Belarusian populations. Gomel and Rechitsa (Belarusian: Rechytsa) followed in 1926. The Belorussian S.S.R. was one of four founding republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R., or Soviet Union), established on December 30, 1922. Beginning under the regime of Joseph Stalin, nationalism was discouraged in the Soviet Union, and the Belorussian S.S.R., like the other constituent republics, was closely controlled. With the commencement of the first five-year plan in 1928, new industries were established in Minsk and other leading towns. In the 1930s purges took the lives of many dissidents, intellectuals, and others in the Belorussian S.S.R.

World War II

Following the German attack on Poland in 1939 and the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact between Stalin's Soviet Union and Hitler's Germany, which divided eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence, the U.S.S.R. attacked Poland from the east. Soviet troops occupied the area up to the Bug River and including the Białystok region. Western Belarusian territory that had been surrendered to Poland in the Treaty of Riga was reinstated as part of the Belorussian S.S.R.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 overran the Belorussian S.S.R., although the garrison of the Brest fortress made a prolonged and courageous stand. During the German retreat in 1944, there was heavy fighting in many areas of the republic, with major battles near Vitebsk, Borisov (Barysaw), and Minsk. German occupation and retreat produced widespread devastation and loss of life. At the end of the war a treaty between the U.S.S.R. and Poland returned western Belarus to Soviet hands. The Polish population was forcibly deported en masse to Poland. With the establishment of the United Nations in 1945, the Belorussian S.S.R. was given a seat in the General Assembly in its own right despite its status as a constituent republic of the U.S.S.R.

The first postwar five-year plan was devoted to the reconstruction of war damage, an aim that it largely achieved. Thereafter, further industrialization took place, with an increasingly rapid growth of the major towns. The population of Minsk reached a million by the early 1970s. Many small towns and the population of a number of rural areas correspondingly declined.

The explosion of the Chernobyl (Chernobyl accident) nuclear power station in Ukraine in 1986 contaminated the greater part of the country with radioactive material and necessitated the creation of an immediate and permanent evacuation zone that included part of Belarus. The accident's legacy of tainted land and human birth defects, as well as the expenditure of government funds required to respond to those problems, continued into the 21st century. (For more information about the Soviet period 【1922–91】, see Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.)

The emergence of independent Belarus

Following Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (Gorbachev, Mikhail)'s initiation of more moderate policies in the mid-1980s, the Belorussian S.S.R. acted somewhat less vigorously than other Soviet republics to break away from the Soviet Union, although there was a steady growth in national separatist feeling. Amid the crisis of central authority in the U.S.S.R. in the early 1990s, the Belorussian S.S.R. declared sovereignty (July 27, 1990) and independence (August 25, 1991). With the collapse of Communist Party rule and the dissolution of the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) in the wake of the failed coup against Gorbachev, the Belorussian S.S.R. changed its name to the Republic of Belarus and joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Legislative elections in Belarus in 1990 had resulted in a Communist-dominated Supreme Soviet that delayed the implementation of a market economy and vacillated for some three years before adopting a new constitution (March 1994). That document created the office of president, to which the pro-Russian Alyaksandr Lukashenka (Lukashenka, Alyaksandr Hrygorevich) was elected in July 1994. Legislative elections followed in 1995; but, owing to the strictures of the Belarusian electoral system (to be seated, candidates had to capture 50 percent of the vote of a turnout of 50 percent of eligible voters), four rounds of voting were required before a quorum was reached in December 1995 (even then, more than 60 seats remained vacant). Many members of the legislature were independents; indeed the largest voting block was not a political party per se but a group that supported Lukashenka, who increasingly sought to dominate the Supreme Soviet. In a referendum in November 1996—the legitimacy of which was widely disputed—Lukashenka won approval for a constitutional change that granted him near-absolute power and extended his five-year term. The parliamentary opposition sought to impeach Lukashenka and to eliminate the office of president, but their efforts were countered by Lukashenka's signing of the revised constitution, which closed parliament and created a new legislative body (from which the opposition was excluded) with greatly reduced powers.

In contrast with much of central and eastern Europe at the time, Lukashenka set Belarus on a course of isolation from the West, maintaining the economics of market socialism. Support for the government's efforts to establish close ties with Russia was widespread but not without opposition. In 1997–99 Belarus entered a political union with Russia that was initially negotiated with Boris Yeltsin (Yeltsin, Boris) but recast by his successor, Vladimir Putin (Putin, Vladimir), who lessened the burden his country had initially agreed to bear in the partnership. Although disputes arose between the two countries over the union's impact on issues such as defense and natural resources, the goal of a common currency, first broached in the early 1990s, was within reach midway through the following decade. With Belarus firmly hitched to Russia's fortunes, its economy responded accordingly—for example, stumbling in 1998 as a result of Russia's financial collapse. Though Russia had long been Belarus's main trading partner, the volume of their trade expanded in the early 21st century as Belarus experienced modest industrial growth.

Many international observers were critical of the Belarusian government and of the essentially authoritarian role Lukashenka adopted from 1996 to 1997. Relations with the European Union were particularly strained. Widely considered the most repressive regime in Europe, Belarus staged undemocratic elections, suppressed political opposition, and silenced the press. Leaders of the political opposition often agitated from exile, while antigovernment figures who arose within Belarus were occasionally beaten, jailed, or "disappeared." Moreover, quality-of-life indicators were on the wane at the turn of the 21st century, with nearly half of the country living in poverty.

Ed.

Additional Reading

A brief survey of important geologic features is offered in R.G. Garetsky et al., Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic: A Guidebook, trans. from Russian (1984). Soviet-oriented presentations of many features of physical and human geography concentrating on the mid-20th century are found in these illustrated booklets, all translated from Russian: V.P. Borodina et al., Soviet Byelorussia (1972); Anatoly Stuk and Yuri Sapozhkov, Byelorussia (1982); V. Borushko, Byelorussia: People, Events, Facts (1983); Mikhail Shimansky, Byelorussia (1986); V. Gulevich and Yu. Gurtovenko, Byelorussia: Years of Achievement (1987); and V. Gulevich, Byelorussia: Questions and Answers (1988). Western publications about Belarus include Nicholas P. Vakar, Belorussia: The Making of a Nation (1956), which includes a survey of traditions and their origins; Ivan S. Lubachko, Belorussia Under Soviet Rule, 1917–1957 (1972), a history of the first half of the Soviet period; Vladimir Seduro, The Byelorussian Theater and Drama (1955), a historical study; and John Sallnow, “Belorussia: The Demographic Transition and the Settlement Network in the 1980s,” Soviet Geography, 28(1):25–33 (January 1987). For historical background of the later Soviet period, see Michael S. Pap (ed.), Russian Empire: Some Aspects of Tsarist and Soviet Colonial Practices (1985), especially the article by Vitaut Kipel, “Byelorussia Under Russian Occupation: Past, Present, Future,” pp. 55–78; appropriate chapters in George W. Simmonds (ed.), Nationalism in the USSR & Eastern Europe in the Era of Brezhnev & Kosygin (1977); John Sallnow, Reform in the Soviet Union: Glasnost and the Future (1989); Bohdan Nahaylo and Victor Swoboda, Soviet Disunion: A History of the Nationalities Problem in the USSR (1990); and Vitaut Kipel and Zora Kipel (eds.), Byelorussian Statehood: Reader and Bibliography (1988). The period of independence is examined in Jan Zaprudnik, Belarus: At a Crossroads in History (1993).

- Folke, Greve (count) Bernadotte (af Wisborg)

- Folkers, Karl August

- Folkestone

- folk high school

- folk literature

- folklore

- folk music

- folk rock

- folk society

- folkway

- Follen, Adolf Ludwig

- Follen, Karl

- Follett, Mary Parker

- follicle-stimulating hormone

- folly

- Folquet De Marseille

- Folsom complex

- Foltz, Clara Shortridge

- Fomalhaut

- Fon

- Fonda, Henry

- Fonda, Jane

- fondant

- Fond du Lac

- Fondi