Roosevelt, Theodore

president of United States

Introduction

bynames Teddy Roosevelt and TR

born October 27, 1858, New York, New York, U.S.

died January 6, 1919, Oyster Bay, New York

26th president of the United States (1901–09) and writer, naturalist, and soldier. He expanded the powers of the presidency and of the federal government in support of the public interest in conflicts between big business and labour and steered the nation toward an active role in world politics, particularly in Europe and Asia. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1906 for mediating an end to the Russo-Japanese War, and he secured the route and began construction of the Panama Canal (1904–14). (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.

26th president of the United States (1901–09) and writer, naturalist, and soldier. He expanded the powers of the presidency and of the federal government in support of the public interest in conflicts between big business and labour and steered the nation toward an active role in world politics, particularly in Europe and Asia. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1906 for mediating an end to the Russo-Japanese War, and he secured the route and began construction of the Panama Canal (1904–14). (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.The early years

Roosevelt was the second of four children born into a long-established, socially prominent family of Dutch and English ancestry; his mother, Martha Bulloch of Georgia, came from a wealthy, slave-owning plantation family. In frail health as a boy, Roosevelt was educated by private tutors. From boyhood, he displayed intense, wide-ranging intellectual curiosity. He graduated from Harvard College, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, in 1880. He then studied briefly at Columbia Law School but soon turned to writing and politics as a career. In 1880 he married Alice Hathaway Lee, by whom he had one daughter, Alice (Longworth, Alice Roosevelt). After his first wife's death, in 1886 he married Edith Kermit Carow (Edith Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Edith)), with whom he lived for the rest of his life at Sagamore Hill, an estate near Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York. They had five children: Theodore, Jr., Kermit, Ethel, Archibald, and Quentin.

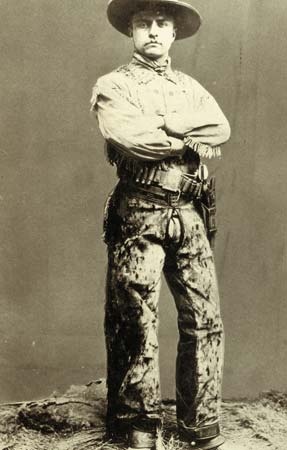

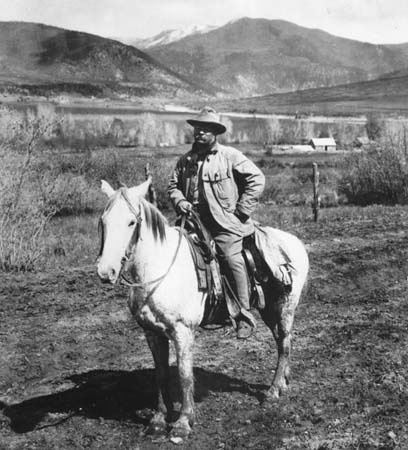

As a child, Roosevelt had suffered from severe asthma, and weak eyesight plagued him throughout his life. By dint of a program of physical exertion, he developed a strong physique and a lifelong love of vigorous activity. He adopted “the strenuous life,” as he entitled his 1901 book, as his ideal, both as an outdoorsman and as a politician.

As a child, Roosevelt had suffered from severe asthma, and weak eyesight plagued him throughout his life. By dint of a program of physical exertion, he developed a strong physique and a lifelong love of vigorous activity. He adopted “the strenuous life,” as he entitled his 1901 book, as his ideal, both as an outdoorsman and as a politician.

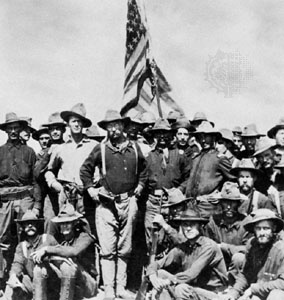

Elected as a Republican to the New York State Assembly at 23, Roosevelt quickly made a name for himself as a foe of corrupt machine politics. In 1884, overcome by grief by the deaths of both his mother and his wife on the same day, he left politics to spend two years on his cattle ranch in the badlands of the Dakota Territory, where he became increasingly concerned about environmental damage to the West and its wildlife. Nonetheless, he did participate as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1884. His attempt to reenter public life in 1886 was unsuccessful; he was defeated in a bid to become mayor of New York City. Roosevelt remained active in politics and again battled corruption as a member of the U.S. Civil Service Commission (1889–95) and as president of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners. Appointed assistant secretary of the navy by President William McKinley (McKinley, William), he vociferously championed a bigger navy and agitated for war with Spain. When war was declared in 1898, he organized the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, known as the Rough Riders (Rough Rider), who were sent to fight in Cuba. Roosevelt was a brave and well-publicized military leader. The charge of the Rough Riders (on foot) up Kettle Hill during the Battle of Santiago (Santiago, Battle of) made him the biggest national hero to come out of the Spanish-American War.

Elected as a Republican to the New York State Assembly at 23, Roosevelt quickly made a name for himself as a foe of corrupt machine politics. In 1884, overcome by grief by the deaths of both his mother and his wife on the same day, he left politics to spend two years on his cattle ranch in the badlands of the Dakota Territory, where he became increasingly concerned about environmental damage to the West and its wildlife. Nonetheless, he did participate as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1884. His attempt to reenter public life in 1886 was unsuccessful; he was defeated in a bid to become mayor of New York City. Roosevelt remained active in politics and again battled corruption as a member of the U.S. Civil Service Commission (1889–95) and as president of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners. Appointed assistant secretary of the navy by President William McKinley (McKinley, William), he vociferously championed a bigger navy and agitated for war with Spain. When war was declared in 1898, he organized the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, known as the Rough Riders (Rough Rider), who were sent to fight in Cuba. Roosevelt was a brave and well-publicized military leader. The charge of the Rough Riders (on foot) up Kettle Hill during the Battle of Santiago (Santiago, Battle of) made him the biggest national hero to come out of the Spanish-American War.On his return, the Republican (Republican Party) bosses in New York tapped Roosevelt to run for governor, despite their doubts about his political loyalty. Elected in 1898, he became an energetic reformer, removing corrupt officials and enacting legislation to regulate corporations and the civil service. His actions irked the party's bosses so much that they conspired to get rid of him by drafting him for the Republican vice presidential nomination in 1900, assuming that his would be a largely ceremonial role.

Elected with McKinley, Roosevelt chafed at his powerless office until September 14, 1901, when McKinley died after being shot by an assassin and he became president. Six weeks short of his 43rd birthday, Roosevelt was the youngest person ever to enter the presidency. Although he promised continuity with McKinley's policies, he transformed the public image of the office at once. He renamed the executive mansion the White House and threw open its doors to entertain cowboys, prizefighters, explorers, writers, and artists. His refusal to shoot a bear cub on a 1902 hunting trip inspired a toy maker to name a stuffed bear after him, and the teddy bear fad soon swept the nation. His young children romped on the White House lawn, and the marriage of his daughter Alice in 1905 to Representative Nicholas Longworth of Ohio became the biggest social event of the decade.

Elected with McKinley, Roosevelt chafed at his powerless office until September 14, 1901, when McKinley died after being shot by an assassin and he became president. Six weeks short of his 43rd birthday, Roosevelt was the youngest person ever to enter the presidency. Although he promised continuity with McKinley's policies, he transformed the public image of the office at once. He renamed the executive mansion the White House and threw open its doors to entertain cowboys, prizefighters, explorers, writers, and artists. His refusal to shoot a bear cub on a 1902 hunting trip inspired a toy maker to name a stuffed bear after him, and the teddy bear fad soon swept the nation. His young children romped on the White House lawn, and the marriage of his daughter Alice in 1905 to Representative Nicholas Longworth of Ohio became the biggest social event of the decade.From what he called the presidency's “bully pulpit,” Roosevelt gave speeches aimed at raising public consciousness about the nation's role in world politics, the need to control the trusts that dominated the economy, the regulation of railroads, and the impact of political corruption. He appointed young, college-educated men to administrative positions. But active as he was, he was cautious in his approach to domestic affairs. Roosevelt recognized that he had become president by accident, and he wanted above all to be elected in 1904. Likewise, as sensitive as he was to popular discontent about big business and political machines, he knew that conservative Republicans who were bitterly opposed to all reforms controlled both houses of Congress. Roosevelt focused his activities on foreign affairs and used his executive power to address problems of business and labour and the conservation of natural resources.

Above all, Roosevelt relished the power of the office and viewed the presidency as an outlet for his unbounded energy. He was a proud and fervent nationalist who willingly bucked the passive Jeffersonian tradition of fearing the rise of a strong chief executive and a powerful central government. “I believe in a strong executive; I believe in power,” he wrote to British historian Sir George Otto Trevelyan. “While President, I have been President, emphatically; I have used every ounce of power there was in the office. … I do not believe that any President ever had as thoroughly good a time as I have had, or has ever enjoyed himself as much.”

The Square Deal

Despite his caution, Roosevelt managed to do enough in his first three years in office to build a platform for election in his own right. In 1902 he cajoled Republican conservatives into creating the Bureau of Corporations with the power to investigate businesses engaged in interstate commerce but without regulatory powers. He also resurrected the nearly defunct Sherman Antitrust Act by bringing a successful suit (antitrust law) to break up a huge railroad conglomerate, the Northern Securities Company. Roosevelt pursued this policy of “trust-busting” by initiating suits against 43 other major corporations during the next seven years. (See primary source document: Controlling the Trusts (Theodore Roosevelt: Controlling the Trusts).)

Despite his caution, Roosevelt managed to do enough in his first three years in office to build a platform for election in his own right. In 1902 he cajoled Republican conservatives into creating the Bureau of Corporations with the power to investigate businesses engaged in interstate commerce but without regulatory powers. He also resurrected the nearly defunct Sherman Antitrust Act by bringing a successful suit (antitrust law) to break up a huge railroad conglomerate, the Northern Securities Company. Roosevelt pursued this policy of “trust-busting” by initiating suits against 43 other major corporations during the next seven years. (See primary source document: Controlling the Trusts (Theodore Roosevelt: Controlling the Trusts).)Also in 1902 Roosevelt intervened in the anthracite coal strike when it threatened to cut off heating fuel for homes, schools, and hospitals. The president publicly asked representatives of capital and labour to meet in the White House and accept his mediation. He also talked about calling in the army to run the mines, and he got Wall Street investment houses to threaten to withhold credit to the coal companies and dump their stocks. The combination of tactics worked to end the strike and gain a modest pay hike for the miners. This was the first time that a president had publicly intervened in a labour dispute at least implicitly on the side of workers. Roosevelt characterized his actions as striving toward a “Square Deal” between capital and labour, and those words became his campaign slogan in the 1904 election.

Once he won that election—overwhelmingly defeating the Democratic contender Alton B. Parker (Parker, Alton B) by 336 to 140 electoral votes—Roosevelt put teeth into his Square Deal programs. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address (Theodore Roosevelt: Inaugural Address).) He pushed Congress to grant powers to the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate interstate railroad rates. The Hepburn Act of 1906 conveyed those powers and created the federal government's first true regulatory agency. Also in 1906, Roosevelt pressed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug and Meat Inspection acts, which created agencies to assure protection to consumers (consumer advocacy). The “muckrakers (muckraker),” investigative journalists of the era, had exposed the squalid conditions of food-processing industries.

Once he won that election—overwhelmingly defeating the Democratic contender Alton B. Parker (Parker, Alton B) by 336 to 140 electoral votes—Roosevelt put teeth into his Square Deal programs. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address (Theodore Roosevelt: Inaugural Address).) He pushed Congress to grant powers to the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate interstate railroad rates. The Hepburn Act of 1906 conveyed those powers and created the federal government's first true regulatory agency. Also in 1906, Roosevelt pressed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug and Meat Inspection acts, which created agencies to assure protection to consumers (consumer advocacy). The “muckrakers (muckraker),” investigative journalists of the era, had exposed the squalid conditions of food-processing industries. Roosevelt's boldest actions came in the area of natural resources. At his urging, Congress created the Forest Service (1905) to manage government-owned forest reserves, and he appointed a fellow conservationist, Gifford Pinchot (Pinchot, Gifford), to head the agency. Simultaneously, Roosevelt exercised existing presidential authority to designate public lands as national forests in order to make them off-limits to commercial exploitation of lumber, minerals, and waterpower. Roosevelt set aside almost five times as much land as all of his predecessors combined, 194 million acres (78.5 million hectares). (See primary source document: The Conservation of Public Lands. (Theodore Roosevelt: The Conservation of Public Lands)) In commemoration of Roosevelt's dedication to conservation, Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota and Theodore Roosevelt Island in Washington, D.C., a 91-acre (37-hectare) wooded island in the Potomac River, were named in his honour.

Roosevelt's boldest actions came in the area of natural resources. At his urging, Congress created the Forest Service (1905) to manage government-owned forest reserves, and he appointed a fellow conservationist, Gifford Pinchot (Pinchot, Gifford), to head the agency. Simultaneously, Roosevelt exercised existing presidential authority to designate public lands as national forests in order to make them off-limits to commercial exploitation of lumber, minerals, and waterpower. Roosevelt set aside almost five times as much land as all of his predecessors combined, 194 million acres (78.5 million hectares). (See primary source document: The Conservation of Public Lands. (Theodore Roosevelt: The Conservation of Public Lands)) In commemoration of Roosevelt's dedication to conservation, Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota and Theodore Roosevelt Island in Washington, D.C., a 91-acre (37-hectare) wooded island in the Potomac River, were named in his honour.Foreign policy

Roosevelt believed that nations, like individuals, should pursue the strenuous life and do their part to maintain peace and order, and he believed that “civilized” nations had a responsibility for stewardship of “barbarous” ones. He knew that taking on the Philippine Islands (Philippines) as an American colony after the Spanish-American War had ended America's isolation from international power politics—a development that he welcomed. Every year he asked for bigger appropriations for the army and navy. Congress cut back on his requests, but by the end of his presidency he had built the U.S. Navy (United States Navy, The) into a major force at sea and reorganized the army along efficient, modern lines.

Several times during Roosevelt's first years in office, European powers threatened to intervene in Latin America (Latin America, history of), ostensibly to collect debts owed them by weak governments there. To meet such threats, he framed a policy statement in 1904 that became known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (see primary source document: Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (Theodore Roosevelt: Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine)). It stated that the United States would not only bar outside intervention in Latin American affairs but would also police the area and guarantee that countries there met their international obligations. In 1905, without congressional approval, Roosevelt forced the Dominican Republic to install an American “economic advisor,” who was in reality the country's financial director.

Quoting an African proverb, Roosevelt claimed that the right way to conduct foreign policy was to “speak softly and carry a big stick (Big Stick Policy).” Roosevelt resorted to big-stick diplomacy most conspicuously in 1903, when he helped Panama to secede from Colombia and gave the United States a Canal Zone. Construction began at once on the Panama Canal, which Roosevelt visited in 1906, the first president to leave the country while in office. He considered the construction of the canal, a symbol of the triumph of American determination and technological know-how, his greatest accomplishment as president. As he later boasted in his autobiography, “I took the Isthmus, started the canal and then left Congress not to debate the canal, but to debate me.” Other examples of wielding the big stick came in 1906 when Roosevelt occupied and set up a military protectorate in Cuba and when he put pressure on Canada in a boundary dispute in Alaska.

Roosevelt showed the soft-spoken, sophisticated side of his diplomacy in dealing with major powers outside the Western Hemisphere. In Asia he was alarmed by Russian expansionism and by rising Japanese power. In 1904–05 he worked to end the Russo-Japanese War by bringing both nations to the Portsmouth Peace Conference (Portsmouth, Treaty of) and mediating between them. More than just to bring peace, Roosevelt wanted to construct a balance of power in Asia that might uphold U.S. interests. In 1907 he defused a diplomatic quarrel caused by anti-Japanese sentiment in California by arranging the so-called Gentlemen's Agreement, which restricted Japanese immigration. In another informal executive agreement, he traded Japan's acceptance of the American position in the Philippines for recognition by the United States of the Japanese conquest of Korea and expansionism in China. Contrary to his bellicose image, Roosevelt privately came to favour withdrawal from the Philippines, judging it to be militarily indefensible, and he renounced any hopes of exerting major power in Asia.

Roosevelt showed the soft-spoken, sophisticated side of his diplomacy in dealing with major powers outside the Western Hemisphere. In Asia he was alarmed by Russian expansionism and by rising Japanese power. In 1904–05 he worked to end the Russo-Japanese War by bringing both nations to the Portsmouth Peace Conference (Portsmouth, Treaty of) and mediating between them. More than just to bring peace, Roosevelt wanted to construct a balance of power in Asia that might uphold U.S. interests. In 1907 he defused a diplomatic quarrel caused by anti-Japanese sentiment in California by arranging the so-called Gentlemen's Agreement, which restricted Japanese immigration. In another informal executive agreement, he traded Japan's acceptance of the American position in the Philippines for recognition by the United States of the Japanese conquest of Korea and expansionism in China. Contrary to his bellicose image, Roosevelt privately came to favour withdrawal from the Philippines, judging it to be militarily indefensible, and he renounced any hopes of exerting major power in Asia.During his second term Roosevelt increasingly feared a general European war. He saw British and U.S. interests as nearly identical, and he was strongly inclined to support Britain behind the scenes in diplomatic controversies. In secret instructions to the U.S. envoys to the Algeciras Conference in 1906, Roosevelt told them to maintain formal American noninvolvement in European affairs but to do nothing that would imperil existing Franco-British understandings, the maintenance of which was “to the best interests of the United States.” Despite his bow toward noninvolvement, Roosevelt had broken with the traditional position of isolation from affairs outside the Western Hemisphere. At Algeciras, U.S. representatives had attended a strictly European diplomatic conference, and their actions favoured Britain and France over Germany.

Last years as president

The end of Roosevelt's presidency was tempestuous. From his bully pulpit, he crusaded against “race suicide,” prompted by his alarm at falling birth rates among white Americans, and he tried to get the country to adopt a simplified system of spelling. Especially after a financial panic in 1907, his already strained relations with Republican conservatives in Congress degenerated into a spiteful stalemate that blocked any further domestic reforms. Roosevelt also moved precipitously and high-handedly to punish a regiment of some 160 African American soldiers, some of whom had allegedly engaged in a riot in Brownsville (Brownsville Affair), Texas, in which a man was shot and killed. Although no one was ever indicted and a trial was never held, Roosevelt assumed all were guilty and issued a dishonourable discharge to every member of the group, depriving them of all benefits; many of the soldiers were close to retirement and several held the Medal of Honor. When Congress decried the president's actions Roosevelt replied, “The only reason I didn't have them hung was because I could not find out which ones … did the shooting.” This incident, along with his establishment of independent agencies within the executive branch and his bypassing of Congress and expanded use of executive orders to set aside public lands beyond the reach of the public, is why some historians see in Roosevelt's presidency the seeds of abuse that flowered in the administrations of later 20th-century presidents. Roosevelt's term ended in March 1909, just four months after his 50th birthday.

Later years

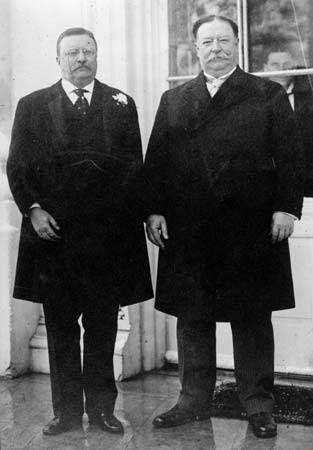

Immediately upon leaving office, Roosevelt embarked on a 10-month hunting safari in Africa and made a triumphal tour of Europe. On his return he became ineluctably drawn into politics. For a while, he tried not to take sides between progressive Republicans who supported his policies and those backing President William Howard Taft (Taft, William Howard). Although Taft was Roosevelt's friend and hand-picked successor, he sided with the party's conservatives and worsened the split in the party. Both policy differences and personal animosity eventually impelled Roosevelt to run against Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912. When that quest failed, he bolted to form the Progressive Party, nicknamed the Bull Moose Party—in a letter to political kingmaker Mark Hanna, Roosevelt had once said “I am as strong as a bull moose and you can use me to the limit.”

Immediately upon leaving office, Roosevelt embarked on a 10-month hunting safari in Africa and made a triumphal tour of Europe. On his return he became ineluctably drawn into politics. For a while, he tried not to take sides between progressive Republicans who supported his policies and those backing President William Howard Taft (Taft, William Howard). Although Taft was Roosevelt's friend and hand-picked successor, he sided with the party's conservatives and worsened the split in the party. Both policy differences and personal animosity eventually impelled Roosevelt to run against Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912. When that quest failed, he bolted to form the Progressive Party, nicknamed the Bull Moose Party—in a letter to political kingmaker Mark Hanna, Roosevelt had once said “I am as strong as a bull moose and you can use me to the limit.”

In the presidential campaign as the Progressive candidate, Roosevelt espoused a “ New Nationalism” that would inspire greater government regulation of the economy and promotion of social welfare. Roosevelt spoke both from conviction and in hopes of attracting votes from reform-minded Democrats. This effort failed, because the Democrats had an attractive, progressive nominee in Woodrow Wilson (Wilson, Woodrow), who won the election with an impressive 435 electoral votes to Roosevelt's 88. Roosevelt had been shot in the chest by a fanatic while campaigning in Wisconsin, but he quickly recovered.

In the presidential campaign as the Progressive candidate, Roosevelt espoused a “ New Nationalism” that would inspire greater government regulation of the economy and promotion of social welfare. Roosevelt spoke both from conviction and in hopes of attracting votes from reform-minded Democrats. This effort failed, because the Democrats had an attractive, progressive nominee in Woodrow Wilson (Wilson, Woodrow), who won the election with an impressive 435 electoral votes to Roosevelt's 88. Roosevelt had been shot in the chest by a fanatic while campaigning in Wisconsin, but he quickly recovered.Since the Progressive Party had managed to elect few candidates to office, Roosevelt knew that it was doomed, and he kept it alive only to bargain for his return to the Republicans. In the meantime, he wrote his autobiography and went on an expedition into the Brazilian jungle, where he contracted a near-fatal illness. When World War I broke out in 1914, he became a fierce partisan of the Allied cause. Although he had some slight hope for the 1916 Republican nomination, he was ready to support almost any candidate who opposed Wilson; he abandoned the Progressives to support the Republican candidate, Charles Evans Hughes (Hughes, Charles Evans), who lost by a narrow margin. After the United States entered the war his anger at Wilson boiled over when his offer to lead a division to France was rejected. His four sons served in combat; two were wounded, and the youngest, Quentin, was killed when his airplane was shot down. By 1918 Roosevelt's support of the war and his harsh attacks on Wilson reconciled Republican conservatives to him, and he was the odds-on favourite for the 1920 nomination. But he died in early January 1919, less than three months after his 60th birthday.

For additional writings by Roosevelt, see The Monroe Doctrine and National Honor (Theodore Roosevelt: The Monroe Doctrine and the National Honor) and False Sentimentality About the Indians (Theodore Roosevelt: False Sentimentality About the Indians).

Cabinet of President Theodore Roosevelt

Cabinet of President Theodore RooseveltThe table provides a list of cabinet members in the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt. Cabinet of President Theodore Roosevelt

Additional Reading

Roosevelt's 2,000 published works include several books and hundreds of articles on history, politics, travel, and natural history; many of them are collected in The Works of Theodore Roosevelt, memorial ed. 24 vol., (1923–26), which also includes the most comprehensive collection of his more than 150,000 personal letters. Among his books, reflecting his wide range of interests, are The Naval War of 1812 (1882), Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1885), Thomas Hart Benton (1886), Essays on Practical Politics (1888), the four-volume The Winning of the West (1889–96), The Strenuous Life (1901), Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography (1913), History as Literature and Other Essays (1913), and A Book Lover's Holidays in the Open (1916). A superb collection of his more important letters appears in Elting E. Morison (compiler and ed.), The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, 8 vol. (1951–54). A Bully Father: Theodore Roosevelt's Letters to His Children (1995), shows his affection for his offspring.Biographies include Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (1979); William H. Harbaugh, The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt, new rev. ed. (1975); and John Milton Cooper, The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt (1983). Henry F. Pringle, Theodore Roosevelt, rev. ed. (1956), although brilliantly written, is perhaps prejudiced against its subject. Comprehensive works on his early life include Carleton Putnam, Theodore Roosevelt (1958), covering the years 1858 to 1886; and David McCullough, Mornings on Horseback (1981).Particularly brilliant short interpretations are G. Wallace Chessman, Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of Power (1969); and John Morton Blum, The Republican Roosevelt, 2nd ed. (1977). David H. Burton, The Learned Presidency: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson (1988), advances the concept that the philosophies of these three presidents helped transform the passive presidencies of the 19th century into the dynamic presidencies of the 20th century. Other special studies of value are George E. Mowry, Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement (1946); Howard K. Beale, Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power (1956); G. Wallace Chessman, Governor Theodore Roosevelt (1965); Frederick W. Marks III, Velvet on Iron: The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt (1979); Lewis L. Gould, The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (1991); and H. Paul Jeffers, Commissioner Roosevelt: The Story of Theodore Roosevelt and the New York City Police, 1895–1897 (1994), and Colonel Roosevelt: Theodore Roosevelt Goes to War, 1897–1898 (1996), covering Roosevelt's participation in the Spanish-American War.General histories of Roosevelt's times are George E. Mowry, The Era of Theodore Roosevelt, 1900–1912 (1958); and Richard H. Collin, Theodore Roosevelt: Culture, Diplomacy, and Expansion: A New View of American Imperialism (1985).

- Giovanni Giolitti

- Giovanni Giorgi

- Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo

- Giovanni Gronchi

- Giovanni Lanfranco

- Giovanni Lanza

- Giovanni Legrenzi

- Giovanni Mardersteig

- Giovanni Maria Falconetto

- Giovanni Maria Lancisi

- Giovanni Maria Nanino

- Giovanni Matteo Mario

- Giovanni Morelli

- Giovanni Morone

- Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni

- Giovanni, Nikki

- Giovanni Paisiello

- Giovanni Paolo Pannini

- Giovanni Papini

- Giovanni Pascoli

- Giovanni Pastrone

- Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Conte Di Concordia

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

- Giovanni Pisano

- Giovanni Pontano