Rwanda

Introduction

also spelled Ruanda, officially Republic of Rwanda, French République Rwandaise, Rwanda Republika y'u Rwanda

landlocked republic lying south of the Equator in east-central Africa. It is bounded on the west by Congo (Kinshasa) and Lake Kivu, on the north by Uganda, on the east by Tanzania, and on the south by Burundi. The capital is Kigali. Like its neighbour to the south, Rwanda is a country of minute dimensions, grinding poverty, and high population density.

Rwanda also shares with Burundi a long history of monarchical rule. Unlike what happened in Burundi, however, the demise of the Rwandan kingship came about through a grass-roots, Hutu-led upheaval that reached its denouement before the country became independent. In Rwanda the state was forged from the ground up, in the crucible of a peasant revolution. For this reason, if Rwanda is described as an ethnocracy, the term nonetheless carries a distinctly democratic connotation inasmuch as the Hutu represent the overwhelming majority of the population.

The land

Relief

The landscape is reminiscent of a tropical Switzerland. Its dominant feature is a chain of mountains of rugged beauty that runs on a north-south axis and forms part of the Congo-Nile divide. From the volcanoes of the Virunga Mountains in the northwest—where the Karisimbi reaches 14,787 feet (4,507 metres)—the altitude drops to 4,000 feet (1,220 metres) in the swampy Kagera (Kagera River) (Akagera) River valley in the east. The interior highlands consist of rolling hills and valleys, yielding to a low-lying depression west of the Congo-Nile divide along the shores of Lake Kivu (Kivu, Lake).

Drainage

Except for the Ruzizi, through which the waters of Lake Kivu empty into Lake Tanganyika, most of the country's rivers are found on the eastern side of the Congo-Nile divide, with the Kagera, the major eastern river, forming much of the boundary between Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania.

Soils

The best soils, formed from volcanic lavas and alluvium, are found, respectively, in the northwest and along the lower portions of the larger river valleys. Elsewhere the largely metamorphic bedrock has produced soils of generally poor quality. The combination of heavy rainfall and deforestation has set in motion a process of extreme soil erosion that requires a burdensome investment of time and energy to curtail.

Climate

Elevation accounts for Rwanda's generally mild temperatures, which average 70° F (21° C) year-round at Kigali, for example, in the interior highlands. There are significant variations, however, between the region of the volcanoes in the northwest, where heavy rainfalls are accompanied by lower average temperatures, and the warmer and drier interior highlands. The average annual rainfall in the latter is about 45 inches (1,140 millimetres) and, except for a short summer dry season, is evenly distributed throughout the year.

Plant and animal life

Only 3 percent of the country consists of natural forest vegetation. Reforestation programs have added eucalyptus trees to previously denuded hillsides and roadsides, though not on a scale sufficient to effectively counteract erosion. A lush, Mediterranean-type vegetation covers the shores of Lake Kivu, which stands in stark contrast to the papyrus swamps of the east and the thick bamboo forests of the Virungas. There, among the volcanoes, lives Rwanda's main tourist attraction, the mountain gorilla. For sheer diversity of animal life, however, no other region can match the resources of the Akagera National Park. Buffalo and zebras, antelope and warthogs, chimpanzees and lions, as well as many rare species—such as the giant pangolin, or anteater—are part of a fauna that also includes elephants, rhinoceroses, and hippopotamuses.

Settlement patterns

Despite a high population density, the dominant pattern is one of extreme dispersal. More than 90 percent of the population is rural and lives in nuclear family compounds scattered on hillsides. Kigali, the capital, was only a hamlet at the time of independence but has grown to become the largest city.

Despite a high population density, the dominant pattern is one of extreme dispersal. More than 90 percent of the population is rural and lives in nuclear family compounds scattered on hillsides. Kigali, the capital, was only a hamlet at the time of independence but has grown to become the largest city.The people

Ethnic composition

As in Burundi, the major ethnic groups are Hutu and Tutsi, respectively accounting for almost 90 percent and about 10 percent of the total population. To these must be added the Twa hunter-gatherers, who constitute less than 1 percent of the population. Other minorities include a small group of Europeans, mostly missionaries and aid officials, a small number of Asian merchants, and a sprinkling of Swahili-speaking Africans from Tanzania and Congo (Kinshasa).

Though the Tutsi are generally taller and of lighter complexion than the Hutu, the physical stereotypes attributed to each group are greatly mitigated by intermarriage. Social differences between them, however, traditionally were profound, as shown by the system of patron-client ties (buhake, or “cattle contract”) through which the Tutsi gained social, economic, and political ascendancy over the Hutu agriculturalists. During the revolution some 300,000 Tutsi were forced out of the country, thus reducing the former ruling aristocracy to an even smaller minority.

Linguistic composition

French and Rwanda (more properly, Kinyarwanda), a Bantu language closely related to Rundi, are the official languages of the country, but only a small fraction of the population speaks French. Swahili (Swahili language) is widely spoken in the towns and is still the principal means of communication with Africans from neighbouring territories.

Religion

Nowhere in Africa has Christianity had a more decisive impact than in Rwanda. The Hutu revolution derived much of its egalitarian inspiration from the teachings of the European clergy, and Catholic seminaries served as recruiting grounds for Hutu leaders. Roman Catholicism claims the allegiance of about two-thirds of the population.

Demographic trends

Rwanda's rate of population increase is one of the highest in central Africa and is far above the productive capacity of the environment. Family-planning programs are virtually nonexistent. Approximately half of the population is under age 16; infant and child mortality rates are among the highest in Africa. Adding to the growing population pressure on the land, some 60,000 Hutu refugees from Burundi live in Rwanda, most of them having fled their homeland during the 1972 holocaust, when an estimated 100,000–150,000 Hutu perished in interethnic violence.

The economy

The country's economy is overwhelmingly agricultural, with coffee exports accounting for more than 70 percent of its foreign exchange and tea for more than 10 percent. An inadequate subsistence agriculture, however, is the dominant feature of the economy, with heavy infusions of foreign aid required to meet chronic food shortages. Rwanda is the largest per capita recipient of foreign aid in Africa. Mineral resources make up from 10 to 15 percent of total exports.

Resources

Mineral resources include, in addition to tin and tungsten (wolfram), tantalite, columbite, and beryl. Methane gas from Lake Kivu is used as a nitrogen fertilizer and is also converted into compressed fuel for trucks. What little gold Rwanda produces is smuggled out of the country. The Mukungwa hydroelectric power installation, the country's major source of electricity, meets only a portion of the country's energy needs, and much of the remainder must be imported from Congo (Kinshasa).

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Intensive cultivation is practiced throughout the country, resulting in a large diversification of food crops. To the main indigenous crops—sorghum and eleusine—must be added corn (maize), potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava (manioc), dry beans, and plantains. While eleusine is harvested in May and sorghum in July, bananas and plantains can be grown throughout the year. Arabica coffee (first introduced by European missionaries), tea, tobacco, and pyrethrum are the principal cash crops, with coffee constituting the prime export. Most of what is left of the small amount of natural forest is found on the slopes of the Virunga Mountains in the northwest. Fishing is widespread in Lake Kivu as well as in the smaller lakes of the interior, most notably Lake Muhazi and Lake Mugesera.

Industry

Aside from small-scale mining operations and limited consumer manufactures (such as textiles, cement, paint, some pharmaceuticals, soap, matches, and furniture), for the most part industrial activities involve the processing of coffee, tea, and other agricultural commodities. Most of the country's industries are located in Kigali.

Finance and trade

Fluctuations in the prices of primary commodities, especially coffee and tea, have had a catastrophic effect on Rwanda's balance of trade, and the country runs large annual trade deficits. In addition, Rwanda must import large quantities of food. Investment programs are almost entirely covered by external sources of financing. Some efforts have been made at promoting closer economic links between Rwanda and its neighbours through such organizations as the Economic Community of Great Lakes Countries and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa.

Transportation

Rwanda claims one of the densest road networks on the continent, though less than 10 percent of it is paved. From Kigali to Ruhengeri and thence to Gisenyi, roads that were once impassable in the rainy season can now be used throughout the year.

Administration and social conditions

Government

The constitution promulgated in 1978 established a presidential form of government. The president at the time, Juvénal Habyarimana, combined the roles of head of state and head of government with that of president of what was then the single ruling party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development. He was returned to office by referenda in 1983 and 1988. A revised constitution was enacted in 1991 that allowed for multiparty participation in government. In 1994, however, after Habyarimana's death, the country slipped into chaos before elections could be held. The legislative body under the 1978 constitution, the unicameral National Development Council, was replaced by the Transitional National Assembly in 1994, which enacted another constitution in 1995.

Education

About three-fifths of the population is literate. In the early 1990s more than two-thirds of the primary-school-age population was enrolled, but the civil strife that began in 1994 severely disrupted the school system. Even prior to 1994, few Rwandans attended secondary schools, as those had space for only 10 percent of the primary school graduates. The National University of Rwanda (1963) has campuses in Butare and Ruhengeri.

Health and welfare

Health conditions in Rwanda are poor. The country has one of the highest percentages of AIDS carriers in Africa. Nutritional deficiencies present an even greater threat to the population, however, along with malaria and tuberculosis. Health facilities are still grossly inadequate, consisting for the most part of poorly equipped health centres and dispensaries. Welfare activities are primarily organized under the auspices of missionary societies.

Cultural life

The arts

Much of Rwanda's traditional cultural heritage revolved around dances, praise songs, and dynastic poems designed to enhance the legitimacy of the Tutsi kingship. Since independence in 1962 another set of traditions has emerged, emphasizing a different cultural stream, identified with a Hutu heritage. Regional dances, including the celebrated hoe dance of the north, are given pride of place in the country's cultural repertoire. Traditional crafts such as basketry, ceramics, and ironworks provide another element of continuity with the past.

Cultural institutions

Rwanda's National Ballet and the Impala Orchestra add considerable lustre to the country's cultural life, the former through a choreography leaning heavily on traditional folk dances and the latter through a distinctly modern musical repertoire. The Association des Écrivains du Rwanda (AER) keeps alive the best of Rwanda's literary traditions, while the bimonthly review Dialogue provides a forum for a vigorous intellectual exchange on a wide range of social and cultural issues.

Press and broadcasting

The absence of stringent government censorship makes for a lively press. In addition to the weekly Imvaho (published in Kinyarwanda) and the monthly La Relève (published in French), the biweekly economic paper Kinyamateka (also in French) deserves mention. Radiodiffusion de la République Rwandaise is the state-run radio broadcaster.

History

This discussion focuses on Rwanda from the 16th century. For a treatment of earlier periods and of the country in its regional context, see Central Africa, history of (Central Africa).

Pre-colonial Rwanda

The area that is now Rwanda is believed to have been initially settled by the Twa, who were closely followed by the Hutu, probably sometime between the 5th and 11th centuries, and then by the Tutsi beginning in the 14th century. Tutsi traditions trace the birth of the Rwanda kingdom to the miraculous feats of its founding hero, Gihanga, whose coming to Rwanda is said to coincide with the advent of civilization. A more historical appraisal, however, would emphasize a long process of Tutsi migrations from the north, culminating in the 16th century with the emergence of a small nuclear kingdom in the central region, ruled by the Tutsi minority, that persisted until the arrival of Europeans in the 19th century. Because of this, Rwanda differs from most countries in sub-Saharan Africa in that its general boundaries were not drawn by European powers but reflect the fully established nation-state that existed until the introduction of German rule.

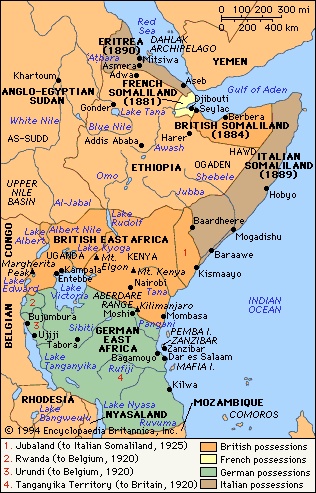

Rwanda under German and Belgian control

From 1894 to 1918, Rwanda, along with Burundi, was part of German East Africa. After Belgium became the administering authority under the mandates system of the League of Nations (Nations, League of), Rwanda and Burundi formed a single administrative entity; they continued to be jointly administered as the Territory of Ruanda-Urundi until the end of the Belgian trusteeship in 1962. By then, however, the two states had evolved radically different political systems. Rwanda had declared itself a republic in January 1961 and forced its monarch (mwami), Kigeri, into exile. Burundi, on the other hand, retained the formal trappings of a constitutional monarchy until 1966.

From 1894 to 1918, Rwanda, along with Burundi, was part of German East Africa. After Belgium became the administering authority under the mandates system of the League of Nations (Nations, League of), Rwanda and Burundi formed a single administrative entity; they continued to be jointly administered as the Territory of Ruanda-Urundi until the end of the Belgian trusteeship in 1962. By then, however, the two states had evolved radically different political systems. Rwanda had declared itself a republic in January 1961 and forced its monarch (mwami), Kigeri, into exile. Burundi, on the other hand, retained the formal trappings of a constitutional monarchy until 1966.The Rwanda revolution was rooted partly in a traditional system of stratification based on an all-embracing “premise of inequality” and partly in a colonial heritage that greatly increased the oppressiveness of the few over the many. Tutsi hegemony was unquestionably more burdensome under Belgian rule than at any time prior to European colonization. By the end of World War II, a growing number of colonial civil servants and missionaries had come to recognize the legitimacy of Hutu claims against the ruling Tutsi minority. The proclamation of the republic a year and a half before the country acceded to independence testifies to the substantial support extended by the trusteeship authorities to the revolution.

Independence and the 1960s

What began as a peasant revolt in November 1959 eventually transformed itself into an organized political movement aimed at the overthrow of the monarchy and the vesting of full political power in Hutu hands. Under the leadership of Grégoire Kayibanda, Rwanda's first president, the Party for Hutu Emancipation (Parti du Mouvement de l'Emancipation du Peuple Hutu) emerged as the spearhead of the revolution. Communal elections were held in 1960, resulting in a massive transfer of power to Hutu elements at the local level. And in the wake of the coup (January 1961) in Gitarama in central Rwanda, which was carried off with the tacit approval of the Belgian authorities, an all-Hutu provisional government came into being. Therefore, by the time that independence was proclaimed in July 1962, the revolution had already run its course. Thousands of Tutsi began fleeing Rwanda, and by early 1964—following a failed Tutsi raid from Burundi—at least 150,000 were in neighbouring countries.

The Habyarimana era

With the elimination of Tutsi elements from the political arena, north-south regional competition among Hutu politicians arose, reflecting the comparatively privileged position of those from the central and southern regions within the party, the government, and the administration. Regional tensions came to a head in July 1973, when a group of army officers from the north overthrew the Kayibanda regime in a bloodless coup and installed a northerner, Maj. Gen. Juvénal Habyarimana. Habyarimana gave a distinctly regional coloration to the institutions of the state during his 21 years in power.

North-south polarities eventually gave way to subregional factions within the northern establishment. By 1980 the principal factions were the Bashiru and Bagoyi elements, respectively identified with the Bushiru and Bugoyi subregions. Habyarimana sided with the Bashiru faction and was the target of an abortive, Bagoyi-inspired coup in April 1980. Thereafter Habyarimana remained in power by holding referenda in 1983 and 1988, thus circumventing the stipulation in the 1978 constitution that the president serve only a single five-year term.

Tension between the Hutu and Tutsi flared in 1990, when the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (Front Patriotique Rwandais; FPR) rebels invaded from Uganda. A cease-fire was negotiated in early 1991, and negotiations between the FPR and the government began in 1992. In the meantime, revisions were made to the 1978 constitution, and the new document, allowing multiparty participation in the government, was promulgated in June 1991. An agreement between the government and the FPR was signed in August 1993 at Arusha, Tanz., that called for the creation of a broad-based transition government that would include the FPR; Hutu extremists were strongly opposed to this plan.

genocide and aftermath

On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying Habyarimana and Burundi Pres. Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down over Kigali; the ensuing crash killed everyone on board. Although the identity of the person or group who fired upon the plane has never been conclusively determined, Hutu extremists were originally thought to have been responsible; later there were allegations that FPR leaders were responsible. The next day Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, a moderate Hutu, was assassinated. Her murder was part of a campaign to eliminate moderate Hutu or Tutsi politicians, with the goal of creating a political vacuum and thus allowing for the formation of the interim government of Hutu extremists that was inaugurated on April 9. Over the next several months the wave of anarchy and mass killings continued, in which the army and Hutu militia groups known as the Interahamwe (“Those Who Attack Together”) and Impuzamugambi (“Those Who Have the Same Goal”) played a central role. The Tutsi-led FPR responded by resuming their fight and were successful in securing most of the country by early July. Later that month a transitional government was established, with Pasteur Bizimungu, a Hutu, as president and Paul Kagame (Kagame, Paul), a Tutsi, as vice president.

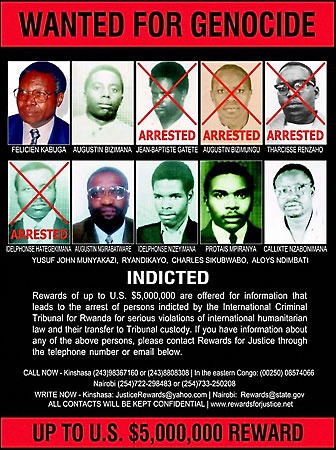

During the genocide more than 800,000 civilians, primarily Tutsi, were killed. As many as 2,000,000 Rwandans, both Hutu and Tutsi, fled, most of them into eastern Zaire (after 1997 called the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo)); the great majority returned to Rwanda in late 1996 and early 1997. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), established by the United Nations Security Council (United Nations) to try the tens of thousands (mostly Hutu) who had committed acts of genocide in 1994, began trying its first cases in 1995. The tremendous number of people to be tried resulted in an inability to proceed in a timely manner, and in 2000 tens of thousands of prisoners continued to await trial. In 2001 the government proposed trying the majority of cases through the traditional gacaca legal system; the gacaca courts were inaugurated in 2002 and began operating in phases over the next several years. The government also periodically granted mass amnesty to prisoners accused of lesser crimes.

During the genocide more than 800,000 civilians, primarily Tutsi, were killed. As many as 2,000,000 Rwandans, both Hutu and Tutsi, fled, most of them into eastern Zaire (after 1997 called the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo)); the great majority returned to Rwanda in late 1996 and early 1997. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), established by the United Nations Security Council (United Nations) to try the tens of thousands (mostly Hutu) who had committed acts of genocide in 1994, began trying its first cases in 1995. The tremendous number of people to be tried resulted in an inability to proceed in a timely manner, and in 2000 tens of thousands of prisoners continued to await trial. In 2001 the government proposed trying the majority of cases through the traditional gacaca legal system; the gacaca courts were inaugurated in 2002 and began operating in phases over the next several years. The government also periodically granted mass amnesty to prisoners accused of lesser crimes.Regional conflict

Meanwhile, in late 1996 Rwanda's military forces entered neighbouring Zaire to expel Hutu extremists, who had fled there after the genocide and were using that country as a base for launching attacks on Rwanda. Frustrated by the lack of support from Zairean president Mobutu Sese Seko regarding these efforts, Rwanda's troops also intervened in the rebellion taking place in that country: along with Ugandan troops, they lent crucial support to rebel Laurent Kabila (Kabila, Laurent), to whom Mobutu eventually relinquished power in 1997. Little more than a year after Kabila became president of what was by then known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda again cited frustration with that country's government over the issue of Hutu extremists and lent support to rebel factions attempting to overthrow Kabila. Because of the number of African countries that intervened in Congo's civil war to support either Kabila or the rebels, the conflict was referred to as Africa's “first world war.” Rwanda faced much international criticism over its involvement in the war, including a suspension of foreign aid. After many attempts at resolution, a peace agreement was reached in 2002 that provided for the withdrawal of Rwandan troops from Congo in exchange for the disarmament and repatriation of Hutu extremist rebels in Congo.

Moving forward

Although Hutu insurgencies continued to occupy Rwanda's government, a new constitution aimed at preventing further ethnic strife in the country was promulgated in 2003. Later that year the first multiparty democratic elections in Rwanda since independence were held; Kagame, who had ascended to the presidency after Bizimungu resigned in 2000, was victorious in securing another term. In 2006 the Rwandan government implemented a significant administrative reorganization, replacing the previous 12 prefectures with 5 larger multiethnic provinces intended to promote power sharing and reduce ethnic conflict. The country's economy, adversely affected by the conflict of the early 1990s, continued to recover gradually. Recovery efforts were aided in 2006, when significant debt relief was granted by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and in 2007, when Rwanda joined the East African Community, a regional trade and development bloc.

In the early 21st century the events of 1994 still weighed heavily in Rwanda. In 2004 Kagame came under fire after a newspaper leaked the findings of a report commissioned by French judge Jean-Louis Bruguière, including allegations that Kagame and other FPR leaders ordered the rocket attack that caused the 1994 plane crash that killed Habyarimana and triggered the genocide (echoing the claims of some Rwandan dissidents); Kagame vehemently denied the allegations. Rwanda severed relations with France in 2006 when Bruguière—claiming jurisdiction because the flight crew members that perished in the crash were French—signed international arrest warrants for several of Kagame's close associates for their alleged roles in the plane crash and requested that Kagame stand trial at the ICTR. As before, Kagame denied having anything to do with the crash and countered by alleging that the French government armed and advised the rebels responsible for the genocide. Later that year Rwanda established a commission to investigate France's role in the genocide. In October 2007 the Rwandan government launched a formal investigation into the 1994 plane crash.

Additional Reading

J.F. Gotanegre, Christian Prioul, and Pierre Sirven, Géographie du Rwanda (1974); and Christian Prioul and Pierre Sirven (eds.), Atlas du Rwanda (1981), provide introductions. The standard work on history is Jan Vansina, L'Évolution du royaume du Rwanda des origines à 1900 (1962). For insights into the rituals and traditions of the monarchy, see Marcel D'Hertefelt and André Coupez (eds.), La Royauté sacrée de l'ancien Rwanda (1964). For a detailed analysis of the dynamics of ethnicity in prerevolutionary Rwanda, Catharine Newbury, The Cohesion of Oppression (1988), remains unsurpassed. The role of the church prior to and during the revolution is analyzed in Ian Linden and Jane Linden, Church and Revolution in Rwanda (1977). Jean-Paul Harroy, Rwanda (1984), is a general survey of the transition to independence, by a former high-ranking colonial civil servant. The country's recent political history is discussed at length in René Lemarchand, Rwanda and Burundi (1970); and Filip Reyntjens, Pouvoir et droit au Rwanda (1985).

- Azteco-Tanoan languages

- Aztec Ruins National Monument

- Azua

- Azuchi-Momoyama period

- Azuela, Mariano

- Azuero Peninsula

- azulejo

- azurite

- Az- Zaqāzīq

- Azzone Dei Porci

- Azīz, al-ʿ

- Aëtius

- Aïn Beïda

- Aïn Sefra

- Aïn Temouchent

- Aïr massif

- Ağrı

- Aśvaghoṣa

- aśvamedha

- Aşık Paşa

- Aşıkpaşazâde

- Aʿshā, al-

- Aḍud ad-Dawlahʿ

- Aḥad Haʿam

- Aḥa Of Shabḥa