Burundi

Introduction

Burundi, flag of country in east-central Africa, south of the Equator. The landlocked country, a historic kingdom, is one of the few countries in Africa whose borders were not determined by colonial rulers.

country in east-central Africa, south of the Equator. The landlocked country, a historic kingdom, is one of the few countries in Africa whose borders were not determined by colonial rulers.

country in east-central Africa, south of the Equator. The landlocked country, a historic kingdom, is one of the few countries in Africa whose borders were not determined by colonial rulers.

country in east-central Africa, south of the Equator. The landlocked country, a historic kingdom, is one of the few countries in Africa whose borders were not determined by colonial rulers. The vast majority of Burundi's population is Hutu, traditionally a farming people. Power, however, has long rested with the Tutsi minority, which historically has controlled the army and most of the economy, particularly the lucrative international export of coffee. Few real cultural differences are distinguishable between the two peoples, and both speak Rundi (Kirundi). Such linguistic homogeneity is rare in sub-Saharan Africa and emphasizes the historically close cultural and ethnic ties among the peoples in Burundi. Even so, ethnic conflict between the Hutu and Tutsi has plagued the country since it gained independence from Belgium in 1962, at a great cost in human life and property. Few Burundians escaped the ensuing anarchy into which the country was plunged when this interethnic violence flared anew in the 1990s, a bloody conflagration that well illustrated the Rundi proverb “Do not call for lightning to strike down your enemies, for it also may strike down your friends.” Neither the presence of an international peacekeeping force beginning in the late 1990s nor the ratification of an agreement to share power between Hutu and Tutsi were immediately effective in curbing interethnic violence, which also spilled into the neighbouring countries of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo). Burundians are now faced with the task of quelling ethnic dissent, promoting unity, and rebuilding the country.

The vast majority of Burundi's population is Hutu, traditionally a farming people. Power, however, has long rested with the Tutsi minority, which historically has controlled the army and most of the economy, particularly the lucrative international export of coffee. Few real cultural differences are distinguishable between the two peoples, and both speak Rundi (Kirundi). Such linguistic homogeneity is rare in sub-Saharan Africa and emphasizes the historically close cultural and ethnic ties among the peoples in Burundi. Even so, ethnic conflict between the Hutu and Tutsi has plagued the country since it gained independence from Belgium in 1962, at a great cost in human life and property. Few Burundians escaped the ensuing anarchy into which the country was plunged when this interethnic violence flared anew in the 1990s, a bloody conflagration that well illustrated the Rundi proverb “Do not call for lightning to strike down your enemies, for it also may strike down your friends.” Neither the presence of an international peacekeeping force beginning in the late 1990s nor the ratification of an agreement to share power between Hutu and Tutsi were immediately effective in curbing interethnic violence, which also spilled into the neighbouring countries of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo). Burundians are now faced with the task of quelling ethnic dissent, promoting unity, and rebuilding the country.Burundi's capital, Bujumbura, lies at the northeastern end of Lake Tanganyika (Tanganyika, Lake). The old section of the city comprises buildings from the German and Belgian colonial periods, as well as a central market filled with hundreds of vendors' booths. The country's second city, Gitega, is also its cultural capital, containing the national museum and several schools. Gitega lies near the southernmost source of the Nile River and a spectacular waterfall, Chutes de la Kagera.

Land (Burundi)

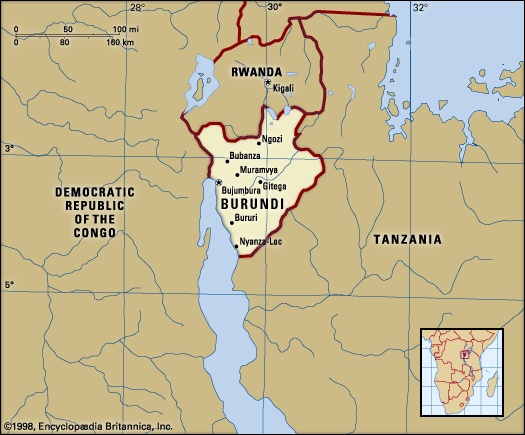

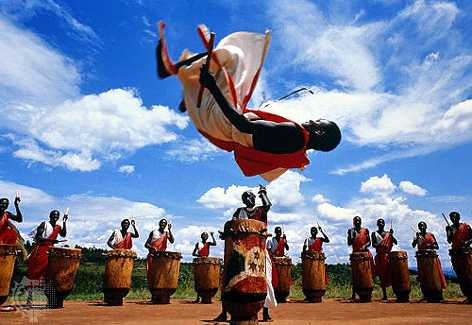

Burundi is bounded by Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east and south, Lake Tanganyika (Tanganyika, Lake) to the southwest, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo) to the west.

Burundi is bounded by Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east and south, Lake Tanganyika (Tanganyika, Lake) to the southwest, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo) to the west.Relief and drainage

Burundi's topography includes the eastern flank of the Western Rift Valley (Rift Valley). A chain of mountains and high plateaus formed from ancient Precambrian rock rises to 9,055 feet (2,760 metres) at Mount Heha, the country's highest point. In the northwest the narrow Imbo valley extends southward from Rwanda to Lake Tanganyika and includes the Rusizi River, which separates Burundi from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Farther south and west, along the shores of Lake Tanganyika, the land rises steeply to form part of the Congo-Nile divide, which reaches elevations of 8,500 feet (2,600 metres). East of the divide, plateaus slope gently to elevations of 5,000–6,000 feet (1,500–1,800 metres) to the southeast; the Ruvyironza River flows northeast, cutting through the plateaus. A few valleys and shallow lakes occupy the northern frontier near Rwanda.

Burundi's topography includes the eastern flank of the Western Rift Valley (Rift Valley). A chain of mountains and high plateaus formed from ancient Precambrian rock rises to 9,055 feet (2,760 metres) at Mount Heha, the country's highest point. In the northwest the narrow Imbo valley extends southward from Rwanda to Lake Tanganyika and includes the Rusizi River, which separates Burundi from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Farther south and west, along the shores of Lake Tanganyika, the land rises steeply to form part of the Congo-Nile divide, which reaches elevations of 8,500 feet (2,600 metres). East of the divide, plateaus slope gently to elevations of 5,000–6,000 feet (1,500–1,800 metres) to the southeast; the Ruvyironza River flows northeast, cutting through the plateaus. A few valleys and shallow lakes occupy the northern frontier near Rwanda.Soils

Light, forest-derived soils predominate, forming a thin layer of humus over lateritic (iron-rich) subsoils. The best soils are formed from alluvium, but they are confined primarily to the lower portions of larger river valleys. Soil erosion, caused by a combination of steep slopes and frequent rainfall, is a serious problem and creates a major constraint on agriculture; ironically, erosion is further exacerbated by the clearing of land for agricultural purposes.

Climate

Elevation is a major factor in Burundi's climate, greatly moderating its tropical character. The country's generally high elevation produces relatively cool temperatures, which average only about 70 °F (21 °C) throughout the year in the central plateau area and usually drop to below 60 °F (15 °C) at night. At lower elevations the annual average is only slightly higher—for example, at Bujumbura in the Imbo valley. Annual precipitation, which averages 60 to 70 inches (1,500 to 1,800 mm) in the highest-lying areas, is only about 40 inches (1,000 mm) on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. There is a short dry season from May to August..

Plant and animal life

The natural forest vegetation has almost entirely disappeared from the landscape and is limited now primarily to higher mountain slopes. On the plateau, wooded savanna is found at higher elevations, giving way to more-open savanna on the lower slopes. poaching has dealt a severe blow to the country's wildlife. The elephant population has virtually disappeared, leaving only warthogs, baboons, and antelope as the less endangered species.

People (Burundi)

Ethnic groups

As in Rwanda, Tutsi and Hutu are the principal ethnic communities, with the Hutu constituting the overwhelming majority and the Tutsi a significant minority. Other groups include the Twa Pygmies and a sprinkling of Swahili-speaking peoples from Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Common perceptions of Tutsi as uniformly tall and graceful and of Hutu as short and stocky do not fit the reality of physical variations because the two groups have frequently intermarried over the centuries.

Traditionally, the Hutu have been farmers, while the Tutsi have been pastoralists. Some regional status differences exist among the Tutsi, with the Tutsi-Banyaruguru clan found primarily in the north of the country and the Tutsi-Bahima primarily in the south. Historically, the Tutsi-Banyaruguru generally dominated precolonial Burundi, while the Tutsi-Bahima have generally dominated Burundi since independence. Society was originally organized around family and clan loyalties. Beginning in the 16th century, these ties were adapted to include a Tutsi monarchy. Intervening between the king (mwani) and the masses was a princely class (ganwa) that kept the ordinary Tutsi and Hutu on equal footing. The relationship between the two groups began to change during the colonial period, when the German and Belgian colonial administrators favoured the Tutsi over the Hutu.

Languages

Burundi's official languages are Rundi (Kirundi), a Bantu (Bantu languages) language that is the standard medium of communication throughout the country, and French. Swahili (Swahili language), the language of trade, is widely spoken in Bujumbura, as is French. It is notable that Rundi is spoken by both the Hutu and Tutsi, who together form the overwhelming majority of the country's population; such linguistic homogeneity is rare in sub-Saharan Africa.

Religion

The country has a relatively large Christian population, of which about three-fifths are Roman Catholic. A large minority and even some Roman Catholics also practice traditional religion. Muslims constitute about one-tenth of the population. Church-state relations have been a focal point of ethnic tension since the 1970s. The government of the Second Republic (1976–87) attempted to curtail the social and educational activities of the Roman Catholic Church because its policies were thought to favour the Hutu over the Tutsi. After a military coup in 1987, the issue was temporarily defused, yet the church continues to be seen by many Tutsi as a dangerously subversive institution.

Settlement patterns

The hilly geography of the country discourages village formation, and traditional family compounds tend to be dispersed rather than concentrated—a key settlement characteristic of the area. This pattern has encouraged isolation rather than community and has contributed to the ongoing ethnic conflict between the Hutu and the Tutsi. Nonetheless, Burundi is heavily populated, with one of the highest densities in Africa. Urban centres are rare, the exceptions including Gitega in the central part of the country, Muyinga and Ngozi in the north, and Bujumbura, the largest city, sprawled along the northern tip of Lake Tanganyika. Civil unrest that began in the early to mid-1990s forced thousands of Hutu to settle in refugee camps spread throughout the countryside and in neighbouring countries. Around the same time, Burundi received an influx of refugees from Rwanda, fleeing from the genocide and subsequent political strife in their country. Rwandans also sought refuge in Burundi in the early 21st century. A large portion of the refugee population consists of women and children.

The hilly geography of the country discourages village formation, and traditional family compounds tend to be dispersed rather than concentrated—a key settlement characteristic of the area. This pattern has encouraged isolation rather than community and has contributed to the ongoing ethnic conflict between the Hutu and the Tutsi. Nonetheless, Burundi is heavily populated, with one of the highest densities in Africa. Urban centres are rare, the exceptions including Gitega in the central part of the country, Muyinga and Ngozi in the north, and Bujumbura, the largest city, sprawled along the northern tip of Lake Tanganyika. Civil unrest that began in the early to mid-1990s forced thousands of Hutu to settle in refugee camps spread throughout the countryside and in neighbouring countries. Around the same time, Burundi received an influx of refugees from Rwanda, fleeing from the genocide and subsequent political strife in their country. Rwandans also sought refuge in Burundi in the early 21st century. A large portion of the refugee population consists of women and children.Demographic trends

Although infant and child mortality rates are high, Burundi's birth rate is above average for central Africa, yet its population is not growing at the same high rate as other countries in Africa, in part because of the mass killings associated with the civil conflict there. About half of the population is under age 15, which assures a continued high growth rate. Only a small proportion of the population is considered urban, the majority of which live in Bujumbura. Life expectancy in Burundi, although low by world standards, is about the average for Africa.

Economy

Agriculture is the economic mainstay of the country, with industrial activities accounting for less than one-fourth of the gross domestic product. Coffee, chiefly arabica, is the principal export crop and source of foreign exchange. Cash crops of lesser importance include cotton and tea. By the late 1990s, more than three-fifths of the country's population were living in poverty—a result of civil strife and the ravages of war, the predominance of traditional subsistence agriculture, the persistence of low income levels, chronic deficits in the balance of trade, and heavy dependence on foreign aid. Western countries and surrounding African countries imposed economic sanctions against Burundi following a Tutsi-led military coup in 1996, which affected all of Burundi's exports and its oil imports. Sanctions were eased beginning in 1997, a regional embargo was lifted in 1999, and much of the country's foreign debt was forgiven in 2005, but the process of economic recovery has been slow.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Approximately half of Burundi's land area is considered cultivable, and about one-third is suitable for pasture. Staple food crops include beans, corn (maize), cassava (manioc), and sorghum. Arabica coffee traditionally has been a major commodity for Burundi. The production of coffee dropped by about half in the 1990s because of civil strife but has since rebounded. Tea and sugar are also major export crops. Large areas of cotton are cultivated, mainly in the Imbo valley; however, cotton output has decreased to less than half the production levels of the early 1990s. Although the density of livestock results in overgrazing, the commercial value of livestock production is virtually nil. By the early 21st century, Burundi's forested area had shrunk to less than 3 percent of the total land area in spite of reforestation efforts. Lake Tanganyika and the smaller lakes and rivers of the interior are rich sources of tilapia and other fish.

Approximately half of Burundi's land area is considered cultivable, and about one-third is suitable for pasture. Staple food crops include beans, corn (maize), cassava (manioc), and sorghum. Arabica coffee traditionally has been a major commodity for Burundi. The production of coffee dropped by about half in the 1990s because of civil strife but has since rebounded. Tea and sugar are also major export crops. Large areas of cotton are cultivated, mainly in the Imbo valley; however, cotton output has decreased to less than half the production levels of the early 1990s. Although the density of livestock results in overgrazing, the commercial value of livestock production is virtually nil. By the early 21st century, Burundi's forested area had shrunk to less than 3 percent of the total land area in spite of reforestation efforts. Lake Tanganyika and the smaller lakes and rivers of the interior are rich sources of tilapia and other fish.Resources and power

Unexploited mineral resources include considerable nickel deposits in the eastern part of the country, as well as significant reserves of vanadium, uranium, and phosphates. Geologic assessments also indicate possible major petroleum reserves beneath Lake Tanganyika and in the Rusizi valley. Mineral production, however, is generally limited and includes niobium, tantalum, gold, tin, and wolframite (a source of tungsten). Peat and firewood are the two major local sources of fuel. Electrical production is mostly hydro-generated, a portion of which is imported.

Manufacturing

Industrial activity is limited to small-scale processing and manufacturing plants, concentrated mostly in Bujumbura. Among the largest industrial enterprises are a brewery and a textile company. Agricultural products such as cotton, coffee, tea, and sugar are also processed in the country. Despite an environment long characterized by civil unrest, the government has remained committed to protecting the industrial sector.

Finance, trade, and services

Banque de la République du Burundi is the country's central bank; it issues the Burundi franc, the national currency, and regulates the operation of national and foreign banks.

Beginning in the 1980s, Burundi experienced a growing trade deficit and increasingly heavy dependence on foreign aid that continued into the 21st century. In 2005, however, Burundi benefited from international debt forgiveness.

On average, export earnings are small (less than half the cost of imports), which reflects a steady growth of consumption and investment coupled with a sharp decline in the international price of coffee (coffee production) and rising import prices. About three-fifths of Burundi's export earnings come from coffee, with tea accounting for much of the remaining value. Chief trading partners include Switzerland, Belgium-Luxembourg, and Kenya and other nearby African countries.

Tourism in Burundi has great potential, but the country's conflicts have severely limited visitors to the region.

Labour and taxation

About nine-tenths of the labour force of Burundi is engaged in agricultural activity. The workers' right to form unions is protected by the Labor Code of Burundi, but there has long been a fragile relationship between unions and the government; union leaders have sometimes been detained, and their records have been confiscated by the police. Since the promulgation of the 2005 constitution, which mandated an increased role for women in government, more Burundian women have entered the workforce, rapidly increasing women's presence not only in government but in development programs and civil service as well.

Revenue sources include taxes on domestic goods and services, international trade, import duties, and social security contributions.

Transportation and telecommunications

In the absence of railroads, only three major routes are available across the country: the northern route by road from Bujumbura to Mombasa (Kenya) via Rwanda; the central route by barge down the Rusizi River to Lake Tanganyika, then to Kigoma (Tanzania); and the southern route across Lake Tanganyika to Kalemie (Democratic Republic of the Congo). A secondary road network connects Bujumbura to various provincial capitals. In 1992 the Bridge of Concord, the country's longest bridge, was opened; it traverses the Rusizi River. An international airport is located in Bujumbura.

By the early 21st century, telephone services had increased, as had the number of mobile cellular phones in use. Internet access is also expanding in Burundi.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

Under the 2005 constitution, power is to be shared by the Hutus and Tutsis. Executive power is vested in the president, who is ordinarily elected directly to a five-year term, renewable once. The president appoints the Council of Ministers. There is a bicameral legislature, with power exercised by the National Assembly, which is mandated to comprise 60 percent Hutu and 40 percent Tutsi, and by the Senate, which includes one Hutu and one Tutsi representative from each province, with three seats reserved for former presidents. In addition, three seats in each house are reserved for the Twa, and at least 30 percent of the seats in both houses are to be held by women. Members of both houses, most of whom are elected by universal suffrage, serve five-year terms.

Under the 2005 constitution, power is to be shared by the Hutus and Tutsis. Executive power is vested in the president, who is ordinarily elected directly to a five-year term, renewable once. The president appoints the Council of Ministers. There is a bicameral legislature, with power exercised by the National Assembly, which is mandated to comprise 60 percent Hutu and 40 percent Tutsi, and by the Senate, which includes one Hutu and one Tutsi representative from each province, with three seats reserved for former presidents. In addition, three seats in each house are reserved for the Twa, and at least 30 percent of the seats in both houses are to be held by women. Members of both houses, most of whom are elected by universal suffrage, serve five-year terms.Local government

Burundi is divided into 17 provinces, which are further divided into communes. Power at the local level rests in the hands of centrally appointed authorities.

Justice

Burundi's legal system is based on German and Belgian civil codes and customary law. The country's highest court is the Supreme Court. Courts of appeal, administrative courts, a constitutional court, and tribunals of first instance, trade, and labour also exist in Burundi.

In 2005 the United Nations Security Council (United Nations) adopted a resolution to create a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as well as a special court to prosecute war crimes and human rights violations.

Political process

Political parties are legally recognized only if they show a national rather than a regional or ethnic membership. Unity for National Progress (Unité pour le Progrès National; UPRONA) was founded in 1958 and dissolved in 1976 after a coup, later reemerging as the country's only recognized political party for a period of time. Many parties have since been created, including Front for Democracy in Burundi (Front pour la Démocratie au Burundi; FRODEBU), which only emerged in 1992 after the constitution promulgated that year provided for multiparty politics; the National Council for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil National pour la Défense de la Democratie; CNDD), established in 1994; and the offshoot National Council for the Defense of Democracy–Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil National pour la Défense de la Democratie–Forces pour la Défense de la Democratie; CNDD-FDD), which formally registered as a party in 2005, although it existed prior to that year.

Women have had the right to vote since 1961, but few have held political positions of power; a notable exception was Sylvie Kinigi (Kinigi, Sylvie), Burundi's first female prime minister, who held the office for almost seven months beginning in July 1993. Female representation in Burundi government increased following the 2005 constitutional mandate that at least 30 percent of the seats in both houses be held by women. Indeed, in the post-transition government installed in 2005, women constituted about one-third of both the National Assembly and the Senate. Burundi's constitution has become a model for other countries in Africa.

Security

Burundi's military consists primarily of an army, with a small air force contingent. Historically, the bulk of the armed forces were Tutsi-Banyaruguru. A new armed forces, mandated to comprise equal numbers of Hutu and Tutsi, was created in December 2004 and absorbed more than 20,000 former rebels. Burundi troops have participated in international peacekeeping missions in Africa.

Health and welfare

The most common health problems stem from communicable diseases and nutritional deficiencies, which account for most infant and child mortality. Those suffering from malnutrition receive some relief from feeding centres set up by international aid workers. Malaria, cholera, measles, influenza, and diarrhea are the major causes of death. Sleeping sickness is widespread in the lakeshore areas, and pulmonary diseases (tuberculosis) are common in the central highlands. HIV/ AIDS is also a serious health concern. At the beginning of the 21st century, the number of reported cases appeared to stabilize in urban locales but had escalated at an alarming rate in rural areas. Burundi has limited hospital facilities and an insufficient number of medical personnel; these resources have been further strained by civil strife.

Housing

The traditional settlement pattern is one of family compounds (rugo), with circular one-room houses—often hidden by banana trees—rising above the hedges of individual enclosures. Urban areas contain colonial-style buildings as well as more-modern housing. Homes that utilized local resources were being built at the beginning of the 21st century. The new dwellings were intended to help relieve a chronic housing shortage, caused in part by the high population density in urban areas and exacerbated by the return of refugees who fled the country during the late 20th-century civil strife.

The traditional settlement pattern is one of family compounds (rugo), with circular one-room houses—often hidden by banana trees—rising above the hedges of individual enclosures. Urban areas contain colonial-style buildings as well as more-modern housing. Homes that utilized local resources were being built at the beginning of the 21st century. The new dwellings were intended to help relieve a chronic housing shortage, caused in part by the high population density in urban areas and exacerbated by the return of refugees who fled the country during the late 20th-century civil strife.Education

About one-half of the country is literate, a rate that is lower than neighbouring countries and well below the world average. Primary education begins at age seven and is compulsory for six years; secondary education, divided into programs of four and then three years, is not mandatory. Education is free, and instruction is in Rundi at the primary level and in French at the secondary level. The distribution of the school-age population shows a striking disproportion in enrollment figures between primary and secondary schools, the former accounting for more than four-fifths of total enrollments. Only a small fraction of primary-school students are admitted to the secondary level, and fewer still are able to gain admission to the University of Burundi at Bujumbura or one of the few colleges in the country.

Ethnic discrimination in schools remains a politically sensitive issue. The overrepresentation of Tutsi at the secondary and university levels translates into the absence of significant avenues of upward mobility for the Hutu majority and the Twa, which means that Tutsi enjoy a virtual monopoly on civil-service positions. Despite outbreaks of ethnic strife, most schools have continued to function amid the unrest.

Cultural life

Daily life, social customs, and the arts

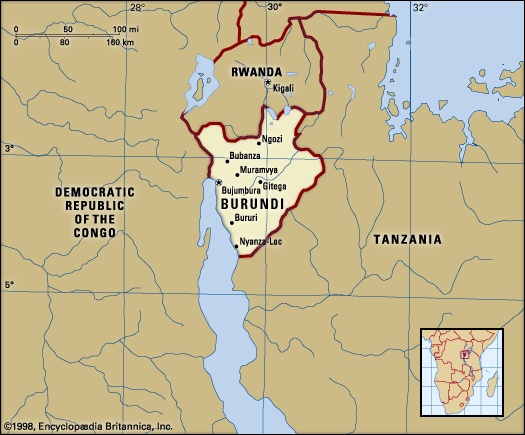

Much of Burundi's rich cultural heritage, most notably folk songs and dances, was intended to extol the virtues of kingship; however, since the fall of the monarchy in 1966 (and particularly after a massacre of Hutu in 1972), such cultural expression has waned. Burundian daily life has since been conditioned by the exigencies of survival in a time of civil strife and ethnic hatred, and many important social institutions, such as the family and the village council, have lost their force, weakened by political chaos and the wholesale displacement of populations. Once widely celebrated events include the annual sorghum festival (umuganuro), the occasion for a magnificent display of traditional dances by court dancers (intore). Also participating in the festival are drummers beating the Karyenda (“sacred drum”), an emblem of the monarchy—their performance is intended to give both musical and symbolic resonance to this festival and to other ceremonial occasions. Government efforts to promote interethnic harmony through displays of a shared cultural heritage have been sporadic and only modestly successful. Burundian museums that celebrate the country's heritage include the National Museum in Gitega and the Living Museum in Bujumbura, which also includes botanical gardens and animal exhibits.

Much of Burundi's rich cultural heritage, most notably folk songs and dances, was intended to extol the virtues of kingship; however, since the fall of the monarchy in 1966 (and particularly after a massacre of Hutu in 1972), such cultural expression has waned. Burundian daily life has since been conditioned by the exigencies of survival in a time of civil strife and ethnic hatred, and many important social institutions, such as the family and the village council, have lost their force, weakened by political chaos and the wholesale displacement of populations. Once widely celebrated events include the annual sorghum festival (umuganuro), the occasion for a magnificent display of traditional dances by court dancers (intore). Also participating in the festival are drummers beating the Karyenda (“sacred drum”), an emblem of the monarchy—their performance is intended to give both musical and symbolic resonance to this festival and to other ceremonial occasions. Government efforts to promote interethnic harmony through displays of a shared cultural heritage have been sporadic and only modestly successful. Burundian museums that celebrate the country's heritage include the National Museum in Gitega and the Living Museum in Bujumbura, which also includes botanical gardens and animal exhibits.Throughout history, Burundians have enjoyed a tradition of expression in the visual arts. Decorated papyrus panels, which feature geometric patterns and often depict themes from Burundian legend, are prized by collectors of ethnic arts, as are Burundian-made swords and drums. Ceramic manufacture, introduced by Italian missionaries in the 1960s, has also been an important form of artistic expression, and Burundian potters have added indigenous elements to this imported medium. Other arts and crafts include basketry and beadwork. The dye usually used to colour Burundian handicrafts is derived from natural plant extracts.

Burundian conversations and social gatherings often feature recitations, singing, and the exchange of jokes, proverbs, and tall tales. Only a few books have been written to date in Rundi, most of them collections of contemporary poetry and folklore. The few writers to have emerged since independence—notably the novelists Séraphin Sésé, Louis Katamari, and Richard Ndayizigamiye, along with the memoirist Michel Kakoya—are little known outside the country. Founded in 1989, the National Library in Bujumbura is a repository for Burundian literature.

Traditional activities such as drumming and dancing contain aspects of both culture and competition: the Intore Dancers, a group that celebrates national folklore, has won numerous international folk dance competitions, and drummers compete with the traditional Karyenda drums. Burundi's best-known cultural export is a troupe of traveling musicians called Les Maîtres-Tambours du Burundi (Drummers of Burundi). This group, made up of as many as 30 percussionists and dancers, produces an energetic, polyrhythmic sound organized around the inkiranya drum. The addition of the amashako drum, which provides a continuous beat, and the complimentary rhythm of the ibishikiso drum complete the impressive sound. The group has been widely influential and has made many recordings. Burundian singer Khadja Nin has also released several recordings, with lyrics in Swahili, Rundi, and French.

Traditional activities such as drumming and dancing contain aspects of both culture and competition: the Intore Dancers, a group that celebrates national folklore, has won numerous international folk dance competitions, and drummers compete with the traditional Karyenda drums. Burundi's best-known cultural export is a troupe of traveling musicians called Les Maîtres-Tambours du Burundi (Drummers of Burundi). This group, made up of as many as 30 percussionists and dancers, produces an energetic, polyrhythmic sound organized around the inkiranya drum. The addition of the amashako drum, which provides a continuous beat, and the complimentary rhythm of the ibishikiso drum complete the impressive sound. The group has been widely influential and has made many recordings. Burundian singer Khadja Nin has also released several recordings, with lyrics in Swahili, Rundi, and French.Sports and recreation

Since the 1990s Burundi has tried to use sports to bring together the country's warring factions. Football (soccer) is popular, and Burundi has competed in several African Cup of Nations championships. Burundians have also excelled in athletics (track and field), none more than Vénuste Niyongabo, who won a gold medal (Burundi's first medal) in the 5,000-metre race at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Media and publishing

Access to radio and television is limited. Although the 2005 constitution provides for freedom of the press, the government still imposes restrictions. In addition, journalists have engaged in self- censorship. Le Renouveau du Burundi, a daily newspaper published in French, is owned by the government. Other periodicals are published on a weekly basis or less frequently.

History

This discussion focuses on Burundi from the 16th century. For a treatment of earlier periods and of the country in its regional context, see Central Africa, history of (Central Africa).

Precolonial Burundi

Unlike most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the boundaries of Burundi were not drawn by European powers. Rather, they reflect a state that was developed by the Burundian monarchy. The country was originally populated by the Twa, a Pygmy hunter-gatherer population. Beginning around AD 1000, Hutu farmers, who now constitute the largest proportion of the population, arrived in the region. Sometime later the Tutsi entered the country, and a Tutsi monarchy developed in the 16th century, founded by Ntare Rushatsi (Ntare I). According to one tradition, Ntare I came from Rwanda; according to other sources, he came from Buha in the southeast, from which he laid the foundation of the original kingdom in the neighbouring Nkoma region. The relationship between the different groups in the state was complex. The king (mwami) was Tutsi, but a princely class (ganwa), which consisted of the potential heirs to the throne, interceded between the king and the Tutsi and Hutu masses.

Identification as either a Tutsi or Hutu was fluid. While physical appearance did correspond somewhat to one's identification (the Tutsi were generally presumed to be light-skinned and tall; the Hutu, dark-skinned and short), the difference between the two groups was not always immediately apparent, owing to intermarriage and the use of a common language (Rundi) by both groups. Tutsis were traditionally cattle owners (cattle were a symbol of wealth in precolonial Burundi), while the Hutu were agriculturalists. However, by societal standards a rich Hutu could be identified as a Tutsi, and a poor Tutsi could be identified as a Hutu.

Burundi under colonial rule

Europeans did not enter Burundi until the second half of the 19th century. The terrain that had made it difficult for slave traders to exploit the country also created problems for European colonizers. English explorers Richard Burton (Burton, Richard) and John Hanning Speke (Speke, John Hanning), generally credited as the first Europeans to visit Burundi, entered the country in 1858. They explored Lake Tanganyika (Tanganyika, Lake) as they searched for the source of the Nile (Nile River). In 1871 two more Britons, Henry Morton Stanley (Stanley, Sir Henry Morton) and David Livingstone (Livingstone, David), also explored the lake.

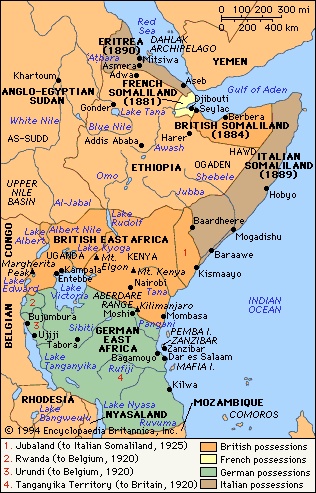

Europeans did not enter Burundi until the second half of the 19th century. The terrain that had made it difficult for slave traders to exploit the country also created problems for European colonizers. English explorers Richard Burton (Burton, Richard) and John Hanning Speke (Speke, John Hanning), generally credited as the first Europeans to visit Burundi, entered the country in 1858. They explored Lake Tanganyika (Tanganyika, Lake) as they searched for the source of the Nile (Nile River). In 1871 two more Britons, Henry Morton Stanley (Stanley, Sir Henry Morton) and David Livingstone (Livingstone, David), also explored the lake. Burundi, along with Rwanda and Tanganyika, became part of the German Protectorate of East Africa in 1890 (see German East Africa). Burundi and Rwanda (as the mandate of Ruanda-Urundi) were awarded to Belgium after World War I, when Germany lost its colonies. Under the Belgian colonial administrators, Burundi was reorganized in the late 1920s, with the result that most chiefs and subchiefs were eliminated.

Burundi, along with Rwanda and Tanganyika, became part of the German Protectorate of East Africa in 1890 (see German East Africa). Burundi and Rwanda (as the mandate of Ruanda-Urundi) were awarded to Belgium after World War I, when Germany lost its colonies. Under the Belgian colonial administrators, Burundi was reorganized in the late 1920s, with the result that most chiefs and subchiefs were eliminated.It would be overly simplistic to blame all of Burundi's postcolonial ethnic troubles on European ignorance of African culture, but such ignorance did contribute significantly to these problems. Assuming that ethnicity could be clearly distinguished by physical characteristics and then using the ethnic differences found in their own countries as models, Germany and especially Belgium created a system whereby the categories of Hutu and Tutsi were no longer fluid. The Tutsi—because of their generally lighter skin and greater height and as a result of European bias toward those physical characteristics—were considered superior to Hutu and given preference in local administration. Thus, power continued to be concentrated in the Tutsi minority.

After World War II, Burundians began to press for independence. Although the traditional leaders of Burundi and Rwanda were denied legal status for a political party they formed in 1955, three years later Unity for National Progress (Unité pour le Progrès National; UPRONA) was established in Burundi. In 1959 the mwami was made a constitutional monarch in Burundi.

Legislative elections were held in 1961 and resulted in victory for UPRONA. Of the 64 legislative seats, the ethnically mixed party won 58, of which 22 were held by Hutu members of UPRONA. The party leader was Prince Rwagasore, a Tutsi and the eldest son of Mwami Mwambutsa. Rwagasore represented populist aspirations and was the strongest supporter of the monarchy. He became prime minister and formed a new government. His assassination on Oct. 13, 1961, ushered in a crisis from which the country has struggled to recover ever since. Despite this crisis, Burundi became independent on July 1, 1962.

The First and Second republics

Discord and violence have marked Burundi since independence. Although bloodshed has not occurred on the scale seen in Rwanda, ethnic conflict has resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths and hundreds of thousands of people being displaced from their homes. The first incident did not occur until January 1965, when Pierre Ngendandumwe, a Hutu, took office as prime minister for the second time, at the request of the constitutional monarch, Mwami Mwambutsa. Ngendandumwe was assassinated by a Tutsi gunman on January 15, before he had a chance to establish a government. Joseph Bamina, another Hutu, then served as prime minister until elections could be held later that year. Although elections gave the Hutu a clear majority of seats in the National Assembly, Mwambutsa ignored the results and appointed a Tutsi—Léopold Biha, his private secretary—prime minister. Mwambutsa insisted that power would continue to rest with the crown, even when he chose to leave the country after an unsuccessful coup led by a group of Hutu officers in October; he decreed that his son, Prince Charles Ndizeyeto, was to rule in his absence.

Control of Burundi fell completely into the hands of the Tutsi before the end of the next year. After the abortive coup, some 34 Hutu officers were executed, and Tutsi control was further strengthened when Michel Micombero was appointed prime minister in July 1966. A Tutsi-Bahima from Bururi province, Micombero had played a key role in thwarting the 1965 coup and in organizing anti-Hutu riots in the countryside. Also in July 1966, Mwambutsa was deposed by his son, who began what was to be an extremely short reign, as he himself was deposed by Tutsi politicians in November. With the formal overthrow of the monarchy and the formal proclamation of the First Republic (with Micombero as president), the last obstacle in the path of Tutsi domination was removed.

No other event cast greater discredit on the First Republic than the genocidal killings (genocide) perpetrated against the Hutu community in April and May 1972. Although Hutu initially killed some 2,000 Tutsi, ultimately an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 Hutu were killed, as well as another 10,000 Tutsi. The carnage took the lives of approximately 5 percent of the population and virtually eliminated all educated Hutu, as well as causing more than 100,000 Hutu to flee the country. Besides creating deep and lasting hatred on both sides of the ethnic divide, the events of 1972 became the source of considerable tension within the Tutsi minority, thus paving the way for the overthrow of Micombero in 1976 and the advent of the Second Republic under the presidency of Jean-Baptiste Bagaza. Though himself a Tutsi-Bahima from Bururi (like Micombero), Bagaza set out to reinvigorate the UPRONA on an unprecedented scale. At the same time, every effort was made to bring the Roman Catholic Church firmly under the control of the state, as the Tutsi-controlled government thought the church's policies favoured the Hutu. As a result of the government's efforts, the activities of the church were repressed.

The Third Republic

The crisis in church-state relations was the critical factor behind Maj. Pierre Buyoya's decision to overthrow the Second Republic in September 1987 and proclaim a Third Republic. Buyoya, also a Tutsi-Bahima from Bururi, took the title of president and presided over a country that was ruled by a 30-member military junta, the Military Committee for National Salvation.

The 1987 coup signaled an important shift of policy on the issue of church-state relations, and, by implication, on the Hutu-Tutsi problem. Buyoya repealed many of the restrictions placed upon the church and released political prisoners he felt had been improperly detained by the previous administration. Ironically, Buyoya's call for liberalization, while significantly raising the expectations of the Hutu masses, did little to alter the rigidly discriminatory practices of Tutsi civil servants in the provinces. The gap between Hutu expectations and the realities of Tutsi control lay at the root of the killings that erupted again in August 1988.

More than 20,000 people were killed in the northern parts of Burundi, the overwhelming majority of Hutu origin. As in 1972, the initial outburst of violence—in the wake of countless provocations by local Tutsi officials—came from Hutu elements. Unlike his predecessor in 1972, however, President Buyoya's response to the crisis was surprisingly conciliatory. For one thing, the existence of a Hutu-Tutsi problem was explicitly recognized by the government, along with the need for appropriate solutions. Moreover, a conscious effort was made to achieve parity of ethnic representation within the government, as evidenced by the cabinet Buyoya formed in October 1988, which contained a Hutu majority. Finally, and most importantly, a national commission was established to make specific recommendations to the government to “protect and strengthen the unity of the people of Burundi.”

Buyoya's apparent progressive leadership led to the adoption of a new constitution in March 1992, which prohibited political organizations that adhered to “tribalism, divisionalism, or violence” and stipulated that all political parties must include both Hutu and Tutsi representatives. There followed the country's first free, democratic election in June 1993, in which Melchior Ndadaye, a Hutu who ran against Buyoya, was elected president. Ndadaye announced amnesty for many political prisoners and created a carefully balanced government of Hutu and Tutsi, including Sylvie Kinigi (Kinigi, Sylvie), a Tutsi woman, as prime minister.

Civil war

Ndadaye was assassinated during an attempted military coup on Oct. 21, 1993, and the wave of violence that followed sparked the country's descent into civil war. As many as 150,000 Tutsi were killed in retribution, and perhaps 50,000 additional people were killed in smaller outbreaks. Amid the violence, leaders of the attempted coup and members of Ndadaye's government vied for power. The main political parties finally chose Cyprien Ntaryamira, a Hutu, as president. Ntaryamira took office in February 1994, but two months later he and Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana were killed when the plane they were on crashed near the airport in Kigali, Rwanda. Fighting intensified, hundreds more were killed, and calls from the United Nations to halt the violence initiated nighttime curfews. In September 1994 a commission agreed to a power-sharing coalition government headed by Sylvestre Ntibantunganya, a Hutu. Fighting continued throughout the country during the nearly two years of coalition government.

The Tutsi-led army staged yet another coup against the government in July 1996 and reinstalled Buyoya as president. He faced considerable internal and international protest, including economic sanctions against the country, and many countries throughout the world had not recognized Buyoya's government by the end of the decade. Economic sanctions were eased in 1997, and an embargo was lifted in 1999.

The path toward peace

Peace talks that began in 1995 among the rival factions were initiated and moderated by Julius Nyerere (Nyerere, Julius), former president of Tanzania. The talks were successfully concluded in 2001 under the leadership of former president of South Africa Nelson Mandela (Mandela, Nelson), who had assumed the role of mediator after Nyerere's death in 1999. Under the terms of the Arusha Agreement, a multinational, interim security contingent would enforce the peace in Burundi. A new government was installed on Nov. 1, 2001. The country was to be led by a Tutsi president (Buyoya) for 18 months and a Hutu president (Domitien Ndayizeye) for the next 18 months. Sporadic fighting continued between Hutu rebel groups and the government, however.

In April 2003 Ndayizeye succeeded Buyoya as president under the terms of the 2001 agreement, and later that year Ndayizeye and rebel leaders signed peace accords that largely ended the civil war. A new power-sharing constitution was promulgated in 2005, and Pierre Nkurunziza, a Hutu, was elected president. Under the terms of the constitution, as the first post-transition president, he was elected by a two-thirds majority of the legislature, rather than by universal suffrage. The following year, the last remaining Hutu rebel group signed a peace agreement with the Burundi government, and there was hope that Burundians would be able to focus on promoting unity and rebuilding the country.

Additional Reading

An introduction to the country's geography can be found in Françoise Cazenave-Piarrot, Alain Cazenave-Piarrot, and Albert Lopez, Géographie du Burundi: le pays et les hommes (1979); and Atlas du Burundi (1979). Useful sources on language, literature, and arts include Ethel M. Albert, “‘Rhetoric,' ‘Logic,' and ‘Poetics' in Burundi: Culture Patterning of Speech Behavior,” American Anthropologist, special issue, pp. 35–54 (winter 1964–65); Alexandre Kimenyi, Kinyarwanda and Kirundi Names: A Semiolinguistic Analysis of Bantu Onomastics (1989); F.M. Rodegem, Précis de grammaire rundi (1967) and Sagesse kirundi (1961); R.P. Bagein, Grammaire kirundi à l'usage des commençants (1951); and the classic Jan Vansina, De la tradition orale: essai de méthode historique (1961).The classic source for precolonial ethnography and history is Hans Mayer, Die Barundi (1916), also available in a French edition excellently annotated by Jean-Pierre Chrétien, Les Barundi (1984). Also useful for this period of history is Emile Mworoha (ed.), Histoire du Burundi: des origines à la fin du XIXe siècle (1987). For colonial history, some useful sources are Michel Lechat, Le Burundi politique; and Joseph Gahama, Le Burundi sous administration Belge (1983), which also includes an English-language summary. Postindependence developments and politics are dealt with at length in René Lemarchand, Rwanda and Burundi (1970); René Lemarchand and David Martin, Selective Genocide in Burundi (1974); René Lemarchand, Burundi: Ethnocide as Discourse and Practice (1994, also published as Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide, 1996); and Marc Manirakiza, La Fin de la monarchie burundaise (1990); and a shorter pamphlet and article are provided by Reginald Kay, Burundi Since the Genocide (1987); and Allison Boyer, “Unity at Last?,” Africa Report, 37:37–40 (March/April 1992). Ellen K. Eggers, Historical Dictionary of Burundi, 2nd ed. (1997), includes an extensive bibliography and a chronology of Burundi's history.

- goldfish

- Goldhaber, Maurice

- Goldie, Sir George

- Goldin, Daniel Saul

- Golding, Louis

- Golding, Sir William

- Goldin, Nan

- gold leaf

- Goldman, Emma

- Goldman, Eric Frederick

- Goldmann, Nahum

- Goldmark, Josephine Clara

- Goldmark, Karl

- Goldmark, Peter Carl

- Goldoni, Carlo

- gold processing

- gold reserve

- gold rush

- Goldsboro

- Goldschmidt, Hans

- Goldschmidt, Meïr Aron

- Goldschmidt, Richard B

- Goldschmidt, Victor Mordechai

- Goldschmidt, Victor Moritz

- Goldsmid, Benjamin and Abraham