shark

fish

Introduction

any of numerous species of cartilaginous fishes of predatory habit that constitute the order Selachii (class Chondrichthyes).

any of numerous species of cartilaginous fishes of predatory habit that constitute the order Selachii (class Chondrichthyes).Sharks, together with rays and skates, make up the subclass Elasmobranchii of the Chondrichthyes. Sharks differ from other elasmobranchs, however, and resemble ordinary fishes, in the fusiform shape of their body and in the location of their gill clefts on each side of the head. Though there are exceptions, sharks typically have a tough skin that is dull gray in colour and is roughened by toothlike scales. They also usually have a muscular, asymmetrical, upturned tail; pointed fins; and a pointed snout extending forward and over a crescentic mouth set with sharp triangular teeth. Sharks have no swim bladder and must swim perpetually to keep from sinking to the bottom.

There are more than 400 living species of sharks, taxonomically grouped into 13 to 22 families according to different authorities. Several larger kinds can be dangerous to humans; smaller ones, called topes, hounds, and dogfishes, are fished commercially.

There are more than 400 living species of sharks, taxonomically grouped into 13 to 22 families according to different authorities. Several larger kinds can be dangerous to humans; smaller ones, called topes, hounds, and dogfishes, are fished commercially.Description and habits

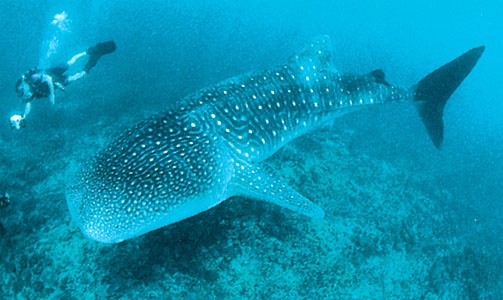

Shark species are nondescript in colour, varying from gray to cream, brown, yellow, slate, or blue (blue shark), and often patterned with spots, bands, marblings, or protuberances. Their vernacular names indicate colours in living species, such as the blue (Prionace), the white (white shark) (Carcharodon), and the lemon (lemon shark) (Negaprion) shark.

Shark species are nondescript in colour, varying from gray to cream, brown, yellow, slate, or blue (blue shark), and often patterned with spots, bands, marblings, or protuberances. Their vernacular names indicate colours in living species, such as the blue (Prionace), the white (white shark) (Carcharodon), and the lemon (lemon shark) (Negaprion) shark. The whale shark (Rhincodon) and basking shark (Cetorhinus), which may reach 15 metres (50 feet) in length and weigh several tons, are harmless giants that subsist on plankton strained from the sea through modified gill rakers. All other sharks prey on small sharks, fish, squid, octopuses, shellfish, and, in some species, trash. The largest among them is the voracious 6-metre (20-foot) great white shark, or man-eater, which attacks seals, dolphins, sea turtles, large fish, and occasionally people. The more sluggish Greenland shark (Somniosus) of cold, deep waters, while half the size of the white shark, feeds on seals, large fish, and even swimming reindeer and scavenges whale carcasses. Normally, sharks feed on fish, often attacking in schools; open-ocean species such as the mackerel (mackerel shark), mako (mako shark), and thresher (thresher shark) sharks frequently feed near the surface and are much sought-after by rod-and-reel sportsmen. Beautifully streamlined and powerful swimmers, these open-ocean sharks are adept at feeding on fast tuna, marlin, and the like. Bottom-feeding species of sharks are stout, blunt-headed forms that tend to have more sluggish habits; the shellfish eaters among them have coarse, pavementlike, crushing teeth. The oddest-looking sharks are the hammerhead (hammerhead shark)s (Sphyrna), whose heads resemble double-headed hammers and have an eye on each stalk.

The whale shark (Rhincodon) and basking shark (Cetorhinus), which may reach 15 metres (50 feet) in length and weigh several tons, are harmless giants that subsist on plankton strained from the sea through modified gill rakers. All other sharks prey on small sharks, fish, squid, octopuses, shellfish, and, in some species, trash. The largest among them is the voracious 6-metre (20-foot) great white shark, or man-eater, which attacks seals, dolphins, sea turtles, large fish, and occasionally people. The more sluggish Greenland shark (Somniosus) of cold, deep waters, while half the size of the white shark, feeds on seals, large fish, and even swimming reindeer and scavenges whale carcasses. Normally, sharks feed on fish, often attacking in schools; open-ocean species such as the mackerel (mackerel shark), mako (mako shark), and thresher (thresher shark) sharks frequently feed near the surface and are much sought-after by rod-and-reel sportsmen. Beautifully streamlined and powerful swimmers, these open-ocean sharks are adept at feeding on fast tuna, marlin, and the like. Bottom-feeding species of sharks are stout, blunt-headed forms that tend to have more sluggish habits; the shellfish eaters among them have coarse, pavementlike, crushing teeth. The oddest-looking sharks are the hammerhead (hammerhead shark)s (Sphyrna), whose heads resemble double-headed hammers and have an eye on each stalk.Fertilization in sharks is internal, the male introducing sperm into the female by means of special copulatory organs (claspers) derived from the pelvic fins. The young in most species hatch from eggs within the female and are born alive.

The origin of sharks is obscure, but their geologic record goes back at least to the Devonian Period (416 to 360 million years ago). Fossil shark-fish appeared in the Middle Devonian Epoch, becoming the dominant vertebrates of the Carboniferous Period (360 to 300 million years ago). Modern sharks appeared in the Early Jurassic Period (200 to 176 million years ago) and by the Cretaceous Period (146 to 66 million years ago) had expanded into present-day families. Overall, evolution has modified shark morphology very little except to improve their feeding and swimming mechanisms. Shark teeth are highly diagnostic of species, both fossil and modern.

Sharks' geographic ranges are not well known; their extensive movements are related to reproductive or feeding activities or to seasonal environmental changes. Tagging returns from large sharks on the East Coast of the United States indicate regular movements between New Jersey and Florida. A tagged spiny dogfish (Squalus) was recovered after traveling about 1,600 km (1,000 miles) in 129 days; a leopard shark (Triakis) after 47 days moved only about 3 km (2 miles). Some members of the Carcharhinus genus enter freshwaters. Riverine sharks, while small to medium-sized, are exceptionally voracious and bold.

Shark behaviour

Information in the second half of the 20th century on shark ecology and individual and group actions provided a better insight into their behaviour. Because large sharks feed on lesser ones, the habit of segregation by size appears vital to their survival; in a uniform grouping, dominance between various species is apparent in feeding competition, suggesting a definite nipping order. All sharks keep clear of hammerheads, whose maneuverability, enhanced by the rudder effect of the head, gives them swimming advantage over other sharks. Sharks circle their prey, disconcertingly appearing out of nowhere and frequently approaching from below. Feeding behaviour is stimulated by numbers and rapid swimming when three or more sharks appear in the presence of food; activity progresses from tight circling to rapid crisscross passes. Under strong feeding stimuli, excitement can intensify into a sensory overload that may result in cannibalistic feeding, or “shark frenzy,” in which injured sharks, regardless of size, are devoured. Sharks may abstain from food for long periods and in captivity may refuse to feed. Feeding is inhibited in large males during courtship and in gravid females while on the nursery grounds. Areas selected for giving birth are usually free of large sharks. In locating food, the shark uses primarily the chemical senses, particularly the olfactory. Visual acuity is adapted to close and long-range location and to distinguishing moving objects more by reflection than by colour, in either dim or bright light. Pit organs over the body serve as distance touch receptors, responding to displacement produced by sound waves. Irregularly pulsed signals below 800 hertz will bring sharks rapidly to a given point, suggesting acoustic orientation from considerable distances.

Feeding habits vary with foraging methods and dentition. Sharks with teeth adapted to shearing and sawing are aided in biting by body motions including a rotation of the body, twisting movement of the head and body, or rapid vibration of the head. In coming to position, the shark protrudes its jaws, erecting and locking the teeth in position.

Hazards to humans

In Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and elsewhere along coasts exposed to the shark nuisance, public beaches often have lookout towers, bells and sirens, or nets. Since 1937, meshing has been employed off Australian beaches to catch sharks, using gill nets suspended between buoys and anchors, parallel to the beach and beyond the breaker line. The nets enmesh sharks from any direction; and, even while touching neither the surface nor the bottom and spaced well apart, the nets give simple, effective control.

The most feared species is the great white shark, whose erratic presence in American coastal waters has given rise to infrequent attacks along the California coast. Other sharks involved in attacks on humans are the tiger (tiger shark), bull (bull shark), oceanic white tip, blue, and hammerhead. Of course, the larger the shark, the more formidable the attack, but several small specimens can be equally hazardous, a fact well attested to by seasonal attacks off the southeastern coast of the United States.

The most feared species is the great white shark, whose erratic presence in American coastal waters has given rise to infrequent attacks along the California coast. Other sharks involved in attacks on humans are the tiger (tiger shark), bull (bull shark), oceanic white tip, blue, and hammerhead. Of course, the larger the shark, the more formidable the attack, but several small specimens can be equally hazardous, a fact well attested to by seasonal attacks off the southeastern coast of the United States.Attacks on humans occur when sharks are hungry, harrassed, or, in some cases, defending territory. Provocation is heightened by the kicking or thrashing vibrations people make in the water (which to sharks resemble the irregular movements of a wounded fish), the presence of speared fish or bait in the water, or the presence of blood from wounds or menstruation. Most injuries occur on the lower limbs and buttocks. It has been estimated that there are about 100 shark attacks worldwide per year. Less than 25 percent of these are fatal, largely owing to hemorrhage and shock. It should be noted, however, that shark attacks are much less frequent than other aquatic mishaps.

- São Vicente Island

- Sänger, Eugen

- Sète

- Sèvres

- deep-scattering layer

- deep-sea fish

- deep-sea trench

- deer

- Deere & Company

- Deere, John

- Deerfield Beach

- Deering, William

- Dee, River

- deer mouse

- Deer, The Book of

- Dee, Ruby

- defamation

- defecation

- Defence of India Act

- defender of the faith

- Defenestration of Prague

- Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

- defense economics

- defense mechanism

- Defense of Rights, Associations for the