Chad

Introduction

Chad, flag of

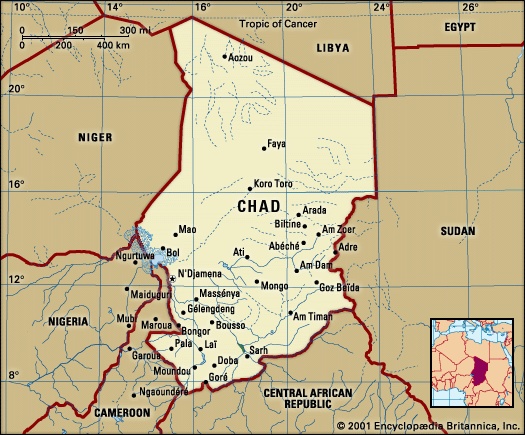

landlocked state in north-central Africa. The capital, N'Djamena (formerly Fort-Lamy), is almost 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometres) by road from the western African coastal ports.

landlocked state in north-central Africa. The capital, N'Djamena (formerly Fort-Lamy), is almost 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometres) by road from the western African coastal ports.

landlocked state in north-central Africa. The capital, N'Djamena (formerly Fort-Lamy), is almost 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometres) by road from the western African coastal ports.

landlocked state in north-central Africa. The capital, N'Djamena (formerly Fort-Lamy), is almost 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometres) by road from the western African coastal ports.Although it is the fifth largest country on the continent, Chad—much of the northern part of which lies in the Sahara—has a population density of only about 20 persons per square mile (8 persons per square kilometre). Most of the population lives by agriculture; cotton is grown in the south, and cattle are raised in the central region. Chad joined the ranks of oil-producing countries in 2003, raising hopes that the revenues generated would improve the country's economic situation.

The land

Chad is bounded on the north by Libya, on the east by The Sudan (Sudan, The), on the south by the Central African Republic, and on the west by Cameroon, Nigeria, and Niger. The frontiers of Chad, which constitute a heritage from the colonial era, do not coincide with either natural or ethnic boundaries.

Chad is bounded on the north by Libya, on the east by The Sudan (Sudan, The), on the south by the Central African Republic, and on the west by Cameroon, Nigeria, and Niger. The frontiers of Chad, which constitute a heritage from the colonial era, do not coincide with either natural or ethnic boundaries.Relief and drainage

In its physical structure Chad consists of a large basin bounded on the north, east, and south by mountains. Lake Chad (Chad, Lake), which represents all that remains of a much larger lake that covered much of the region in earlier geologic periods, is situated in the centre of the western frontier; it is 922 feet (281 metres) above sea level. The lowest altitude of the basin is the Djourab Depression, which is 573 feet above sea level.

In the early Holocene, possibly until as recently as 7,000 years ago, the lake stood at a level of about 1,100 feet above sea level, or some 180 feet higher than today, and was as much as 550 feet deep. At that stage Mega-Chad, as it has been called, occupied an area of some 130,000 square miles and overflowed southward via the present-day Kébi River and then over the Gauthiot Falls westward to the Benue River and the Atlantic Ocean. Older dune systems, flooded by Mega-Chad, form linear islands in the present lake and extend hundreds of miles to the east, the interdunal hollows being occupied by diatomites and other lake sediments.

The mountains that rim the basin include the volcanic Tibesti Massif to the north (of which the highest point is Mount Koussi (Koussi, Mount), with an altitude of 11,204 feet 【3,415 metres】), the sandstone peaks of the Ennedi Plateau to the northeast, the crystalline rock mountains of the Ouaddaï (Wadai) region to the east, and the Oubangui Plateau to the south. The semicircle is completed to the southwest by the mountains of Adamawa and Mandara, which lie mostly beyond the frontier in Cameroon and Nigeria.

Chad's river network is virtually limited to the Chari (Chari River) and Logone rivers (Logone River) and their tributaries, which flow from the southeast to feed Lake Chad. The remaining Chad waterways are either seasonal or are of insignificant size. The Chari, which arises from headstreams in the Central African Republic to the south, is later joined from the east by the Salamat Wadi and from the west by the Ouham River, its largest tributary. After entering an ill-defined area of swampland between Niellim and Dourbali, it flows through a large delta into Lake Chad. The Chari is about 750 miles in length and has a flow that normally varies between 600 and 12,000 cubic feet (17,000 to 340,000 litres) per second, according to the season. The Logone, which for some of its course runs along the Cameroon frontier, is formed by the junction of the Pendé and Mbéré rivers; its flow varies between 170 and 3,000 cubic feet per second, and its course is more than 600 miles long before it joins the Chari at N'Djamena. The level of Lake Chad fluctuates according to the flow of these rivers, as well as according to the degree of precipitation, evaporation, and seepage. The droughts of the 1970s and early '80s in the Sahel region of western Africa reduced the lake to record low levels. By 1985 it had been reduced to a pool, immediately to the north of the Chari–Logone mouth, occupying about 1,000 square miles.

Soils

Several types of soil formation occur in Chad, apart from the sand of the desert zone and the sheer rock of the mountainous areas. On the south side of Lake Chad the soils are derived from clayey deposits that accumulated on the floor of Mega-Chad. Along the seasonally flooded banks of the Chari and Logone rivers and the Salamat Wadi, hydromorphic (waterlogged) soils occur. Tropical iron-bearing soils, red in colour, are found on the exposed folds and mounds of the Ouaddaï region's upland slopes. In the Kanem region (area north of Lake Chad) subarid soils are characteristic, except in the depressions that occur between the dunes on the shores of Lake Chad, where hydromorphic soils liable to salinization are found.

Climate

Chad's wide range in latitudes (that extend southward from the tropic of Cancer for more than 15°) is matched by a climatic range that varies from wet and dry tropical to hot arid. At the towns of Moundou and Sarh, in the wet and dry tropical zone, between 32 and 48 inches (800 and 1,200 millimetres) of rain falls annually between May and October. In the central semiarid tropical (Sahel) zone, where N'Djamena is situated, between 12 and 32 inches of rain falls between June and September. In the north rains are infrequent, with an annual average of less than one inch being recorded at Largeau.

Chad thus has one relatively short rainy season. The dry season, which lasts from December to February everywhere in the country, is relatively cool, with daytime temperatures of about 85° to 95° F (29° to 35° C) and nighttime temperatures that drop to about 55° F (13° C). From March onward it becomes very hot until the first heavy rains fall. At N'Djamena, for example, daytime temperatures average more than 100° F (38° C) between March and June. Heavy rains begin at N'Djamena in July, and average daytime temperatures drop to the low 90s F (mid-30s C), but nighttime temperatures remain in the 70s F (20s C) until the onset of N'Djamena's dry, cool season in November.

Plant and animal life

Three vegetation zones, correlated with the rainfall, may be distinguished. These are a wet and dry tropical zone in the south, characterized by shrubs, tall grasses, and scattered broad-leaved deciduous trees; a semiarid tropical (Sahel) zone, in which savanna vegetation gradually merges into a region of thorn bushes and open steppe country; and a hot arid zone, composed of dunes and plateaus in which vegetation is scarce and occasional palm oases are to be found.

The tall grasses and the extensive marshes of the savanna zone have an abundant wildlife. There large mammals—such as the elephant, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, warthog, giraffe, antelope, lion, leopard, and cheetah—coexist with a wide assortment of birds and reptiles. The rivers and the lake are among the richest in fish of all African waters. The humid regions also contain swarms of insects, some of which are dangerous.

Settlement patterns

Conditioned by soil and climate, land is put to different uses in the three vegetation zones. In the wet and dry tropical zone, farmers cultivate rice and sorghum in the clay soils and peanuts (groundnuts) and millet in the sandier areas. Manioc, recently introduced, is also cultivated. Between the latitudes of 11° and 15° N, the retreat of the rivers in the dry season leaves behind flooded depressions called yaere, allowing a second crop of “dry season” sorghum, or berbere, to be cultivated. Since 1928 the cultivation of cotton in the area between the Logone and Chari rivers has been encouraged, first by the colonial administration and since 1960 by the national government. Cotton cultivation, while tending to upset the ecological balance by exhausting the soil, has nevertheless resulted in the introduction of a cash economy in place of a barter economy. The cultivation of rice, begun in 1958 in irrigated plots in the Bongor region, south of N'Djamena, has proved successful. A joint venture with France introduced sugarcane cultivation in the 1970s. Improved strains of both cotton and rice have produced higher yields.

The intermediate semiarid tropical zone is inhabited by both sedentary cultivators and nomadic pastoralists. The northern limit of the bloodsucking tsetse fly, deadly to cattle and the carrier of sleeping sickness to humans, is latitude 10° N; beyond this limit, extensive stock raising begins, occasionally in association with agriculture, as for example in the Kanem region. The inhabitants raise millet and grow peanuts wherever the mean annual rainfall exceeds 15 inches. Cotton is grown where and when rainfall exceeds 30 inches. Large herds of cattle migrate over the semiarid tropical zone in search of pasture and water. In very limited areas bordering Lake Chad, the presence of water allows three harvests of wheat and corn (maize) to be grown in some years on irrigated plots called polders. Elsewhere the seminomadic inhabitants are almost completely dependent upon rainfall. Drought has had serious repercussions, affecting both the livestock and the pastoralists, whose livelihood depends on milk products.

In the hot arid zone, nomads live among their herds of camels, frequenting palm groves in such oases as that at Largeau. Farther north, in the Tibesti Mountains, tiny plots of millet, tomatoes, peppers, and other minor crops are grown for local consumption, often in the shade of date palms. These garden crops depend on irrigation from springs breaking out from the sandstones and volcanic rocks at widely separated points and shallow wells in the sandy sediments flooring steep-sided valleys.

Urban life in Chad is virtually restricted to the capital, N'Djamena. Founded in the early years of the 20th century, the city has undergone a dramatic growth in population due not to a high degree of industrialization but to the other attractions of urban life. The majority of the population is engaged in commerce. Other major towns, such as Sarh (formerly Fort-Archambault), Moundou, and Abéché, are less urbanized than is the capital.

The people

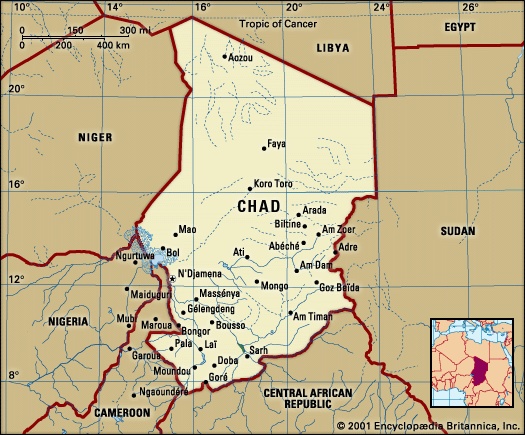

The population of Chad presents a tapestry composed of different languages, peoples, and religions that is remarkable even amid the variety of Africa. The degree of variety encountered in Chad underscores the significance of the region as a crossroads of linguistic, social, and cultural interchange.

The population of Chad presents a tapestry composed of different languages, peoples, and religions that is remarkable even amid the variety of Africa. The degree of variety encountered in Chad underscores the significance of the region as a crossroads of linguistic, social, and cultural interchange.Linguistic groups

More than 100 different languages and dialects are spoken in the country. Although many of these languages are imperfectly recorded, they may be divided into the following 12 groupings: (1) the Sara-Bongo-Bagirmi group, representing languages spoken by about one million people in southern and central Chad, (2) the Mundang-Tuburi-Mbum languages, which are spoken by several hundred thousand people in southwestern Chad, (3) the Chado-Hamitic (Chadic languages) group, which is related to the Hausa spoken in Nigeria, (4) the Kanembu-Zaghawa languages, spoken in the north, mostly by nomads, (5) the Maba (Maban languages) group, spoken in the vicinity of Abéché and throughout the Ouaddaï region of eastern Chad, (6) the Tama languages, spoken in the Abéché, Adré, Goz Béïda, and Am Dam regions, (7) Daju (Daju languages), spoken in the area of Goz Béïda and Am Dam, (8) some languages of the Central African groups, particularly Sango (also the lingua franca of the Central African Republic), which are spoken in the south, (9) the Bua group, spoken in southern and central Chad, (10) the Somrai group, spoken in western and central Chad, and (11) Mimi and (12) Fur (Fur languages), both spoken in the extreme east.

In addition to this rich assortment, Arabic (Arabic language) is also spoken in various forms and is one of the two official languages of the country. The dialects spoken by the nomadic Arabs differ from the tongue spoken by settled Arabs. A simplified Arabic is spoken in towns and markets; its diffusion is linked to that of Islām.

French (French language) is the other official language, and it is used in communications and in instruction as well, although the national radio network also broadcasts in Arabic, Sara Madjingay, Tuburi, and Mundang. While a regional form of French, showing local linguistic and environmental peculiarities, is spoken widely in the towns, its penetration into the countryside is uneven. Its use is closely linked to the development of education.

Ethnic groups

As might be expected, the linguistic variety reflects an ethnic composition of great complexity. A general classification may nevertheless be made, again in terms of the three regions of Chad.

In the wet and dry tropical zone, the Sara group forms a significant element of the population in the central parts of the Chari and Logone river basins. The Laka and Mbum peoples live to the west of the Sara groups and, like the Gula and Tumak of the Goundi area, are culturally distinct from their Sara neighbours. Along the banks of the Chari and Logone rivers, and in the region between the two rivers, are found the Tangale peoples.

Among the inhabitants of the semiarid tropical zone are the Barma of Bagirmi, the founders of the kingdom of the same name; they are surrounded by groups of Kanuri, Fulani, Hausa, and Arabs (Arab), many of whom have come from outside Chad itself. Along the lower courses of the Logone and Chari rivers are the Kotoko, who are supposedly descended from the ancient Sao population that formerly lived in the region. The Yedina (Buduma) and Kuri inhabit the Lake Chad region and, in the Kanem area, are associated with the Kanembu and Tunjur, who are of Arabic origin. All of these groups are sedentary and coexist with Daza, Kreda, and Arab nomads. The Hadjeray (of the Guera Massif) and Abou Telfân are composed of refugee populations who, living on their mountainous terrain, have resisted various invasions. On the plains surrounding the Hadjeray are the Bulala, Kuka, and the Midogo, who are sedentary peoples. In the eastern region of Ouaddaï live the Maba, among whom the Kado once formed an aristocracy. They constitute a nucleus surrounded by a host of other groups who, while possessing their own languages, nevertheless constitute a distinct cultural unit. The Tama to the north and the Daju to the south have formed their own separate sultanates. Throughout the Ouaddaï region are found groups of nomadic Arabs, who are also found in other parts of south central Chad. Despite their widespread diffusion, these Arabs represent a single ethnic group composed of a multitude of tribes. In Kanem other Arabs, mostly of Libyan origin, are also found.

In the northern Chad regions of Tibesti, Borkou, and Ennedi the population is composed of black nomads. Their dialects are related to those of the Kanembu and Kanuri.

Religious groups

The great majority of Muslims are found in the north and east of Chad. Islāmization in Kanem came very early and was followed by the conversion to Islām of the major political entities of the region, such as the sultanates of Wadai, Bagirmi, and Fitri, and—more recently—the Saharan region. Islām is well established in most major towns and wherever Arab populations are found. It has attracted a wide variety of ethnic groups and has forged a certain unity which, however, has not resulted in the complete elimination of various local practices and customs.

animism flourishes in the southern part of the country and in the mountainous regions of Guera. The various traditional religions provide a strong basis for cohesion in the villages where they are practiced. Despite a diversity of beliefs, a widespread common feature is the socioreligious initiation of young people into adult society.

In Chad, as elsewhere, Christian missionary work has not affected the Muslim population; it has been directed toward the animist populations in the cities in the western regions south of the Chari River and in parts of the central uplands area. There are three Roman Catholic dioceses, with an archbishop at N'Djamena. There are some Protestant mission groups, and an effort has been made to form a Chad Evangelical church.

Demographic trends

More than two-fifths of the population of Chad are under the age of 15. Nearly one-fourth of the people are considered to be urban dwellers, the majority living in N'Djamena. The population is increasing at a comparatively low rate for an African country. Emigration—especially to The Sudan, Nigeria, and northern Cameroon—resulting from drought, conflict, and famine, may help to account for this.

The economy

Resources

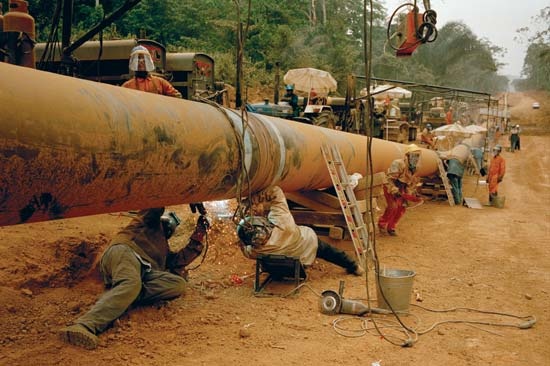

Historically, Chad's principal mineral resource was natron (a complex sodium carbonate), which is dug up in the Lake Chad and Borkou areas and is used as salt and in the preparation of soap and medicines. Annual production is a few thousand tons. The discovery of oil (petroleum) north of Lake Chad led to further exploration and development, and in 2003 Chad began producing oil, which quickly became the country's most important resource and export. There are indications of deposits of gold in the Ouaddaï area, uranium in the Ennedi Plateau area, uranium and wolframite in the Aozou Strip in the far north, and bauxite near Laï.

Historically, Chad's principal mineral resource was natron (a complex sodium carbonate), which is dug up in the Lake Chad and Borkou areas and is used as salt and in the preparation of soap and medicines. Annual production is a few thousand tons. The discovery of oil (petroleum) north of Lake Chad led to further exploration and development, and in 2003 Chad began producing oil, which quickly became the country's most important resource and export. There are indications of deposits of gold in the Ouaddaï area, uranium in the Ennedi Plateau area, uranium and wolframite in the Aozou Strip in the far north, and bauxite near Laï.Agriculture and fishing

Cotton is Chad's primary agricultural product. Although it is basically an export crop, the processing of raw cotton provides employment for a majority of those in industry and accounts for some of Chad's export earnings. Most of the cotton fibre ginned in Chad's processing plants is exported to Europe and the United States.

Chad's livestock constitutes another important economic resource and is primarily distributed across central Chad. Much of this wealth is not reflected in the national cash economy, however, and livestock products form less than one-tenth of exports. There is a refrigerated meat-processing plant at Sarh, which exports meat to the Congo and Gabon. The government has tried to improve livestock by introducing stronger breeds and production by building new slaughterhouses.

Rice is produced in the Chari valley and in southwestern Chad, and wheat is grown along the shores of Lake Chad; little of either crop is processed commercially.

About half the fish caught is salted and dried for export. Most fish are caught in the Lake Chad, Chari, and Logone basins.

About half the fish caught is salted and dried for export. Most fish are caught in the Lake Chad, Chari, and Logone basins.Industry

In the early 21st century, much industrial development centred around the exploitation and production of oil. Many established industries, such as cotton ginning, slaughtering, and the milling of wheat and rice, are associated with agriculture. Secondary industries are few and rely on imported materials.

In the early 21st century, much industrial development centred around the exploitation and production of oil. Many established industries, such as cotton ginning, slaughtering, and the milling of wheat and rice, are associated with agriculture. Secondary industries are few and rely on imported materials.Finance and trade

The country relies heavily on foreign financial assistance. The sums received exceed export earnings and in many years constitute as much as a quarter of the gross national product. The main imports are machinery and equipment, food products, and textiles, most of which come from the European Union, Cameroon, and the United States. Petroleum is by far the main export; raw cotton, live cattle, meat, and fish are exported. Primary export partners are the United States and China.

Transportation

Chad's economic development is primarily contingent upon the establishment of an effective transportation network. There are three access routes to the sea—by road, river, or rail, through neighbouring countries. Most of the country's roads and trails are impractical for travel during part of the rainy season. Year-round traffic is possible on gravel-surfaced roads and on a paved section between N'Djamena and Guélendeng. Three major road axes, forming a triangle joining N'Djamena, Sarh, and Abéché, were completed but have fallen into disrepair. In 1985 a bridge across the Chari River to Kousseri, Cameroon, ended N'Djamena's dependence on an unreliable ferry for its road connection through Cameroon to the railhead at Ngaoundéré and the sea.

Rivers are of secondary importance due to great seasonal fluctuations in water levels, with only about half of the total river length navigable year-round. The Chari is navigable between Sarh and N'Djamena between August and December, and the Logone is navigable between Mondou and N'Djamena in September and October. Two railways have their terminals near the Chad border. Across the Nigerian frontier to the west there is a railhead at Maiduguri, which links up with the Nigerian ports of Lagos and Port Harcourt. Across the Sudanese frontier to the east is the railhead at Nyala, which leads eventually to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Air traffic plays an important role in the Chad economy, in view of the paucity of alternative means. N'Djamena's airport can accommodate large jets, and there are more than 40 secondary airports.

Administration and social conditions

Government

Under the constitution of 1996, Chad is a republic. The executive branch of the government is represented by the president, who serves as the chief of state, and a prime minister, who serves as the head of government. The president is elected by universal suffrage to a five-year term and is responsible for appointing the prime minister and the Council of Ministers. The legislative branch is served by the National Assembly, comprising members who are directly elected to four-year terms. For administrative purposes, Chad is divided into regions.

Chad's judicial system comprises the Supreme Court, a Constitutional Council, and criminal and magistrate courts. A High Court of Justice, made up of National Assembly members elected by their peers, tries any cases of treason involving members of the government.

Education

The size of the country, the dispersion of populations, and the occasional reluctance to send children to school all constitute educational problems that the government is endeavouring to overcome. Less than one-half of the school-age population is enrolled. Missions and public education services are responsible for primary education. Secondary and technical education is also available. The University of Chad, founded in 1971, offers higher education, and some Chad students study abroad.

Health and welfare

There are major hospitals at N'Djamena, Sarh, Moundou, Bongor, and Abéché. Other health facilities include dispensaries and infirmaries dispersed throughout the country. The government, in cooperation with the World Health Organization, has developed a health education and training program. Campaigns have been conducted against malaria, sleeping sickness, leprosy, and other diseases.

Cultural life

With its rich variety of peoples and languages, Chad possesses a valuable cultural heritage. The government has in the past encouraged cultural activities and institutions. There is a national museum of prehistoric and traditional artifacts. The Chad Cultural Centre seeks to awaken a conscious interest in national traditions. The lives of the people have been so dislocated by war and famine since the 1960s, however, that Chad is more impoverished than ever, and the main efforts of the government and people are now directed toward survival.

With its rich variety of peoples and languages, Chad possesses a valuable cultural heritage. The government has in the past encouraged cultural activities and institutions. There is a national museum of prehistoric and traditional artifacts. The Chad Cultural Centre seeks to awaken a conscious interest in national traditions. The lives of the people have been so dislocated by war and famine since the 1960s, however, that Chad is more impoverished than ever, and the main efforts of the government and people are now directed toward survival.History

The region of the eastern Sahara and Sudan from Fezzan, Bilma, and Chad in the west to the Nile valley in the east was well peopled in Neolithic times, as discovered sites attest. Probably typical of the earliest populations were the dark-skinned cave dwellers described by Herodotus as inhabiting the country south of Fezzan. The ethnographic history of the region is that of gradual modification of this basic stock by the continual infiltration of nomadic and increasingly Arabicized white African elements, entering from the north via Fezzan and Tibesti and, especially after the 14th century, from the Nile valley via Darfur. According to legend, the country around Lake Chad was originally occupied by the Sao. This vanished people is probably represented today by the Kotoko, in whose country, along the banks of the Logone and Chari, was unearthed in the 1950s a medieval culture notable for work in terra-cotta and bronze.

The relatively large and politically sophisticated kingdoms of the central Sudan were the creation of Saharan Imazighen (Berbers (Berber)), drawn southward by their continuous search for pasturage and easily able to impose their hegemony on the fragmentary indigenous societies of agriculturalists. This process was intensified by the expansion of Islam. There are indications of a large immigration of pagan Imazighen into the central Sudan early in the 8th century.

From the 16th to the 19th century

The most important of these states, Kanem-Bornu, which was at the height of its power in the later 16th century, owed its preeminence to its command of the southern terminus of the trans-Saharan trade route to Tripoli.

Products of the Islamized Sudanic culture diffused from Kanem were the kingdoms of Bagirmi (Bagirmi, Kingdom of) and Ouaddaï (Wadai), which emerged in the early years of the 17th century out of the process of conversion to Islam. In the 18th century the Arab dynasty of Ouaddaï was able to throw off the suzerainty of Darfur and extend its territories by the conquest of eastern Kanem. Slave raiding at the expense of animist populations to the south constituted an important element in the prosperity of all these Muslim states. In the 19th century, however, they were in full decline, torn by wars and internecine feuds. In the years 1883–93 they all fell to the Sudanese adventurer Rābiḥ az-Zubayr.

French administration

By this time the partition of Africa among the European powers was entering its final phase. Rābiḥ was overthrown in 1900, and the traditional Kanembu dynasty was reestablished under French protection. Chad became part of the federation of French Equatorial Africa in 1910. The pacification of the whole area of the present republic was barely completed by 1914, and between the wars French rule was unprogressive. A pact between Italy and France that would have ceded the Aozou Strip to Italian-ruled Libya was never ratified by the French National Assembly, but it provided a pretext for Libya to seize the territory in 1973. During World War II Chad gave unhesitating support to the Free French cause. After 1945 the territory shared in the constitutional advance of French Equatorial Africa. In 1946 it became an overseas territory of the French Republic.

Independence

A large measure of autonomy was conceded under the constitutional law of 1957, when the first territorial government was formed by Gabriel Lisette, a West Indian who had become the leader of the Chad Progressive Party (PPT). An autonomous republic within the French Community was proclaimed in November 1958, and complete independence in the restructured community was attained on August 11, 1960. The country's stability was endangered by tensions between the black and often Christian populations of the more economically progressive southwest and the conservative, Muslim, nonblack leadership of the old feudal states of the north, and its problems were further complicated by Libyan involvement.

Lisette was removed by an associate more acceptable to some of the opposition, N'Garta (François) Tombalbaye, a southern trade union leader, who became the first president of the republic. In March 1961 Tombalbaye achieved a fusion of the PPT with the principal opposition party, the National African Party (PNA), to form a new Union for the Progress of Chad. An alleged conspiracy by Muslim elements, however, led in 1963 to the dissolution of the National Assembly, a brief state of emergency, and the arrest of the leading ministers formerly associated with the PNA. Only government candidates ran in the new elections in December 1963, ushering in the one-party state.

Civil war

In the mid-1960s two guerrilla movements emerged. The Front for the National Liberation of Chad (Frolinat) was established in 1966 and operated primarily in the north from its headquarters at the southern Libyan oasis of Al-Kufrah, while the smaller Chad National Front (FNT) operated in the east-central region. Both groups aimed at the overthrow of the existing government, the reduction of French influence in Chad, and closer association with the Arab states of North Africa. Heavy fighting occurred in 1969 and 1970, and French military forces were brought in to suppress the revolts.

By the end of the 1970s, civil war had become not so much a conflict between Chad's Muslim northern region and the black southern region as a struggle between northern political factions. Libyan troops were brought in at President Goukouni Oueddei's request in December 1980 and were withdrawn, again at his request, in November 1981. In a reverse movement the Armed Forces of the North (FAN) of Hissène Habré, which had retreated into The Sudan in December 1980, reoccupied all the important towns in eastern Chad in November 1981. Peacekeeping forces of the Organization of African Unity withdrew in 1982, and Habré formed a new government in October of the same year. Simultaneously, an opposition government under the leadership of Goukouni was established, with Libyan military support, at Bardaï in the north. After heavy fighting in 1983–84 Habré's FAN prevailed, aided by French troops. France withdrew its troops in 1984 but Libya refused to do so. Libya launched incursions deeper into Chad in 1986, and they were turned back by government forces with help from France and the United States.

In early 1987 Habré's forces recovered the territory in northern Chad that had been under Libyan control and for a few weeks reoccupied Aozou. When this oasis was retaken by Muammar al-Qaddafi's Libyan forces, Habré retaliated by raiding Maaten es Sarra, which is well inside Libya. A truce was called in September 1987.

Continuing conflict

Habré continued to face threats to his regime. In April 1989 an unsuccessful coup attempt was led by the interior minister, Brahim Mahamot Itno, and two key military advisers, Hassan Djamouss and Idriss Déby. Itno was arrested and Djamouss was killed, but Déby escaped and began new attacks a year later. By late 1990 his Movement for Chadian National Salvation forces had captured Abéché, and Habré fled the country. Déby suspended the constitution and formed a new government with himself as president. Although it was reported that he had received arms from Libya, he denied Libyan involvement and promised to establish a multiparty democracy in Chad.

Déby's takeover of the government was not without resistance. In 1991 and 1992, there were several attacks and coup attempts by opposition forces, many of whom were still aligned with Habré, but Déby maintained his grip on the government and the country. A national conference was held in 1993 to establish a transitional government, and Déby was officially designated interim president. In 1996 a new constitution was approved and Déby was elected president in the first multiparty presidential elections held in Chad's history. Peace was still fragile, however, and periodic skirmishes with opposition groups developed into a full rebellion in late 1998 when the Mouvement pour la Démocratie et la Justice au Tchad (MDJT) began an offensive in the northern part of the country. Other opposition groups later joined forces with the MDJT, and the rebellion continued into the 21st century.

In 2001 Déby was reelected amid allegations of fraud by his opponents; however, international observers found the electoral proceedings largely to be valid. Meanwhile, Déby's government was still coping with major rebel offensives, until peace accords in 2002 and 2003 essentially ended most of the fighting for a few years. Also in 2003, years of planning and construction came to fruition when Chad became an oil (petroleum)-producing country; the revenues generated from this undertaking had the potential to transform the country's economic situation.

Despite the progress Déby's government made with promoting peace and creating an opportunity for economic prosperity, there were additional coup attempts, including those in 2004 and 2006. Rebel offensives also resumed, most notably in 2006, prior to Déby's reelection to a third term as president, and in 2008, when rebels reached N'Djamena before retreating; many Chadians were displaced by the fighting. Several rebel leaders involved in the 2008 offensive were tried in absentia in August of that year, as was former president Habré, who was suspected of directing rebel activity in Chad while living in exile in Senegal. Habré and the rebel leaders were found guilty of attempting to overthrow Déby's government and were sentenced to death. Habré also faced charges in Senegal regarding politically motivated killings and acts of torture allegedly committed during his rule in Chad; Senegal pursued these charges at the request of the African Union.

Despite the progress Déby's government made with promoting peace and creating an opportunity for economic prosperity, there were additional coup attempts, including those in 2004 and 2006. Rebel offensives also resumed, most notably in 2006, prior to Déby's reelection to a third term as president, and in 2008, when rebels reached N'Djamena before retreating; many Chadians were displaced by the fighting. Several rebel leaders involved in the 2008 offensive were tried in absentia in August of that year, as was former president Habré, who was suspected of directing rebel activity in Chad while living in exile in Senegal. Habré and the rebel leaders were found guilty of attempting to overthrow Déby's government and were sentenced to death. Habré also faced charges in Senegal regarding politically motivated killings and acts of torture allegedly committed during his rule in Chad; Senegal pursued these charges at the request of the African Union.

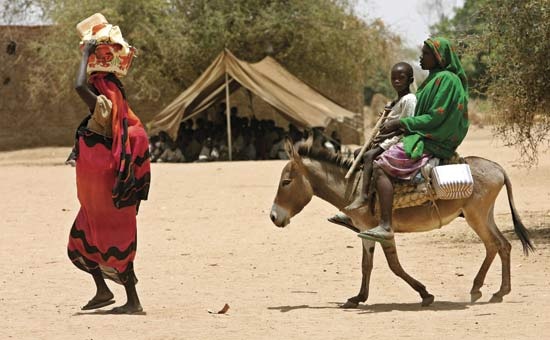

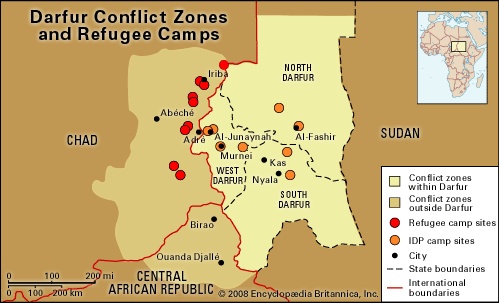

In addition to internal conflicts, at the beginning of the 21st century Chad had problems along its border with neighbouring countries Niger, Central African Republic, and most notably The Sudan (Sudan, history of the). In early 2003, fighting in the Darfur region of western Sudan sent thousands of Sudanese fleeing to Chad; by early 2005 it was estimated that there were some 200,000 refugees in Chad. Chadian troops were drawn into the conflict periodically, as Sudanese militias crossed over the border into Chad while chasing Sudanese rebels or attacking refugee camps; Chadian rebels were also suspected of operating from bases in The Sudan. Both Chad and The Sudan accused each other of supporting rebel activity in the other's country.

In addition to internal conflicts, at the beginning of the 21st century Chad had problems along its border with neighbouring countries Niger, Central African Republic, and most notably The Sudan (Sudan, history of the). In early 2003, fighting in the Darfur region of western Sudan sent thousands of Sudanese fleeing to Chad; by early 2005 it was estimated that there were some 200,000 refugees in Chad. Chadian troops were drawn into the conflict periodically, as Sudanese militias crossed over the border into Chad while chasing Sudanese rebels or attacking refugee camps; Chadian rebels were also suspected of operating from bases in The Sudan. Both Chad and The Sudan accused each other of supporting rebel activity in the other's country.Additional Reading

Harold D. Nelson et al., Area Handbook for Chad (1972), is still a useful introduction. See also Pierre Hugot, Le Tchad (1965); Mario Azevedo (ed.), Cameroon and Chad in Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (1989); and Jean Cabot and Christian Bouquet, Atlas pratique du Tchad (1972). Ethnographic studies include Jean Chapelle, Nomades noirs du Sahara (1958, reissued 1982), the authoritative study on the Teda; Albert Le Rouvreur, Sahéliens et sahariens du Tchad (1962), information about the northern and eastern populations; and Jean Chapelle, Le Peuple tchadien (1980). Politics and government are treated in Georges Diguimbaye and Robert Langue, L'Essor du Tchad (1969); and Michael P. Kelley, A State in Disarray: Conditions of Chad's Survival (1986), discussing dependency. Samuel Decalo, Historical Dictionary of Chad, 2nd ed. (1987), has an extensive bibliography. Early history is discussed in Jean Paul Lebeuf, Archéologie tchadienne: les Sao du Cameroun et du Tchad (1962); and Jean Paul Lebeuf and A. Masson Detourbet, La Civilisation du Tchad (1950). Jacques Le Cornec, Histoire politique du Tchad, de 1900 à 1962 (1963), provides information on the colonial era and the first years of independence. Robert Buijtenhuijs, Le Frolinat et les révoltes populaires du Tchad, 1965–76 (1978), and Le Frolinat et les guerres civiles du Tchad (1977–1984) (1987), are the best sources of information on Chad's civil wars. The boundary disputes are discussed in Bernard Lanne, Tchad-Libye, 2nd ed. (1986).

- Retief, Piet

- retina

- retinitis pigmentosa

- retinopathy of prematurity

- retinospora

- Retiro Park

- retort

- retraining program

- retriever

- retroflex

- retrograde motion

- retrovirus

- retting

- Retton, Mary Lou

- Rett syndrome

- Retzius, Anders Adolf

- Retzius, Magnus Gustaf

- Retz, Jean-François-Paul de Gondi, Cardinal de

- Reuben

- Reubeni, David

- Reuben Leon Kahn

- Reuchlin, Johannes

- Reumert, Poul

- Reus

- Reuss