small body

astronomy

any natural solar system object other than the Sun and the major planets and dwarf planets and their satellites (moons). The small bodies populate the solar system in vast numbers and include the rocky asteroids (asteroid), or minor planets, the predominantly icy comets (comet), and the fragments of these bodies—commonly called meteoroids (meteor and meteoroid)—over a continuum of sizes down to microscopic grains known as interplanetary dust particles (interplanetary dust particle) or micrometeoroids. The term small body is sometimes restricted to objects that can be observed telescopically while still outside Earth's atmosphere. In practice, this results in a lower limit of a few metres on the diameter of a small body.

any natural solar system object other than the Sun and the major planets and dwarf planets and their satellites (moons). The small bodies populate the solar system in vast numbers and include the rocky asteroids (asteroid), or minor planets, the predominantly icy comets (comet), and the fragments of these bodies—commonly called meteoroids (meteor and meteoroid)—over a continuum of sizes down to microscopic grains known as interplanetary dust particles (interplanetary dust particle) or micrometeoroids. The term small body is sometimes restricted to objects that can be observed telescopically while still outside Earth's atmosphere. In practice, this results in a lower limit of a few metres on the diameter of a small body.The use of meteoroid has expanded to describe any small chunk of matter in interplanetary space, especially one less than a few tens of metres in size. The term formerly was limited to small bodies that were near enough to Earth to eventually enter its atmosphere. In this narrower meaning, meteoroid is usually linked with the terms meteor, meteorite, or both. As a meteoroid travels through the atmosphere, friction heats it up, creating a glowing trail of hot ionized gases (plasma) called a meteor (meteor and meteoroid). If the object survives its passage through the atmosphere and is recovered on the ground, it is called a meteorite. Over 99 percent of meteorites are fragments of asteroids. A small group is known to be of lunar origin, and a second group is generally acknowledged to have come from Mars (see Mars: Meteorites from Mars (Mars)). There is also reason to believe that some are fragments of the rocky remnants of comets, although this remains to be firmly established.

The largest known small bodies, in the conventional sense, are several icy Kuiper belt objects (see below) found orbiting the Sun beyond the orbit of Neptune. On the basis of their brightnesses, their sizes were estimated to approach or exceed that of the dwarf planet Pluto's largest moon, Charon, which is 1,250 km (780 miles) in diameter, or about one-third the diameter of Earth's Moon. The previous titleholder, Ceres—which is the largest main-belt asteroid and is now distinguished as a dwarf planet—is roughly 920 km (570 miles) in diameter. (The distant Kuiper belt object Eris, although estimated to be larger than Pluto, is also designated a dwarf planet rather than a small body.) In the 1990s, astronomers recognized that Pluto, which has a diameter of 2,300 km (1,400 miles) and which had been classified as a planet from its discovery in 1930 until 2006, is a giant icy leftover from the time when the planets formed. Primarily for historical reasons, the moons of the planets are not considered small bodies. Nevertheless, many moons are asteroid-size or smaller, and some are probably captured asteroids or comet nuclei.

Although small bodies are found throughout the solar system, most of those known are concentrated in several regions. Those regions in which they travel in fairly stable orbits include (1) the main asteroid belt, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, (2) the gravitationally stable points (Lagrangian points (Lagrangian point)) along the orbital paths of Jupiter and Mars—and perhaps of other planets as well—where objects called Trojan asteroids (asteroid) are clustered (see celestial mechanics: The restricted three-body problem (celestial mechanics)), (3) the Kuiper belt, a disk-shaped zone of icy bodies whose members are also called trans-Neptunian objects because they all have orbits beyond that of Neptune, and (4) the spherical Oort cloud of icy bodies inferred to be orbiting the Sun at distances typically more than 1,000 times that of Neptune or Pluto. In none of the above categories is Sedna, an object discovered in 2003 in the outer reaches of the solar system that is perhaps as large as two-thirds the size of Pluto. Sedna has a highly elliptical orbit in which its closest approach to the Sun is billions of kilometres beyond the recognized extent of the Kuiper belt; it may be a member of a population of objects lying between the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud.

Other small bodies travel in unstable orbits that cross the paths of one or more of the planets. These include (1) most observed comets, (2) near-Earth asteroids (asteroid), most with orbits that cross either Earth's orbit or Mars's orbit and some with orbits that lie mostly or entirely inside Earth's orbit and cross the orbits of Venus or of both Venus and Mercury while closely approaching Earth's, (3) Centaur objects (Centaur object), icy bodies that are thought to have been gravitationally perturbed out of the Kuiper belt and now travel mainly between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune, and (4) individual idiosyncratic planet-crossing objects such as the asteroid Hidalgo, which travels between the inner edge of the asteroid belt and a point just beyond the orbit of Saturn. All objects in planet-crossing orbits eventually collide with the Sun or a planet or are permanently ejected from the solar system, although some survive for long periods (up to hundreds of millions of years) because of stabilizing resonances.

Essentially all the small bodies are thought to be remnant material from the planet-building process that took place during the formation of the solar system from the solar nebula. (See solar system: Formation of the solar nebula (solar system).) Near the hot nascent Sun, closer than Jupiter's present orbit, only the less-volatile high-freezing-point substances such as metals and silicates could condense from the nebula. Beginning as tiny grains, this material gradually accreted under mutual gravitational influence to become large rocky bodies up to hundreds of kilometres in diameter. Most of these large objects, called planetesimals (planetesimal), ultimately combined to form the dense, rocky planets of the inner solar system (Mercury through Mars). In the outer solar system, near Jupiter's present orbit and beyond, temperatures were cool enough to allow abundant volatile substances such as water and carbon dioxide to condense to their ices. Although rocky planetesimals likewise accreted there, the significant additional mass contributed by the ices allowed the growth of the low-density, gas-rich outer planets (Jupiter through Neptune).

Nevertheless, in the inner and the outer solar system, there remained rocky bodies and predominantly icy bodies, respectively, that were never incorporated into planets or captured as planetary moons. Today, in the inner solar system, these are represented chiefly by the asteroids and their fragments; in the outer solar system, by the objects in and derived from the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud. Comets (comet) originate, and most are still located, in the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud. Except for the very largest Kuiper belt objects (diameters greater than about 100 km 【60 miles】), comets in the Kuiper belt and beyond are unobservable because of their great distances from Earth. It is not until they enter the realm of the planets that they develop comas and tails.

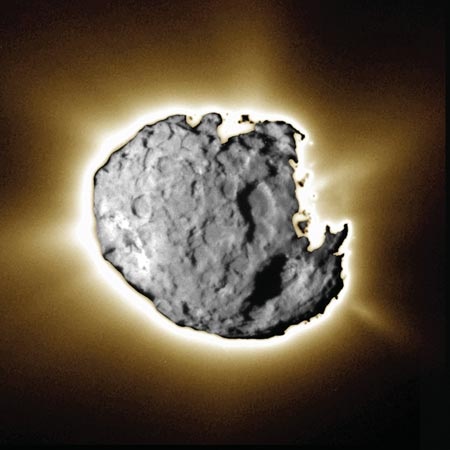

There are several characteristics based on physical differences, location, and orbital properties that traditionally have distinguished comets from asteroids. An object is classified as a comet when it displays “cometary activity”—i.e., a coma or tail (or any evidence of gas or dust coming from it). Objects in the Oort cloud, although they may not all have formed in their present location, are considered to be comet nuclei. Because of their great distance from the Sun, they do not display cometary activity. Nevertheless, they are believed to be made of the same volatile material as the observed comets and so have the potential to become active. Finally, any object on a nonreturning (parabolic or hyperbolic) orbit is generally considered to be a comet.

There are several characteristics based on physical differences, location, and orbital properties that traditionally have distinguished comets from asteroids. An object is classified as a comet when it displays “cometary activity”—i.e., a coma or tail (or any evidence of gas or dust coming from it). Objects in the Oort cloud, although they may not all have formed in their present location, are considered to be comet nuclei. Because of their great distance from the Sun, they do not display cometary activity. Nevertheless, they are believed to be made of the same volatile material as the observed comets and so have the potential to become active. Finally, any object on a nonreturning (parabolic or hyperbolic) orbit is generally considered to be a comet.Although these distinctions apply most of the time, they are not always sufficient to classify an individual object as an asteroid or a comet. For example, an object found to be receding from the Sun on a nonreturning orbit and displaying no cometary activity could be a comet, or it could be a planet-crossing asteroid being ejected from the solar system after a close encounter with a planet, most likely Jupiter. Again, objects on some planet-crossing orbits may have originated in either the Kuiper belt or the asteroid belt. Unless such an object reveals itself by displaying cometary activity, there is usually no way to determine its origin and thus to classify it unequivocally. The object may have formed as an icy body but lost its volatile materials during a series of passes into the inner solar system. Its burned-out remnant of rocky material would presently have more physical characteristics in common with asteroids than with other comets.

- gastroenterology

- gastroesophageal reflux disease

- gastrointestinal system drugs

- gastrointestinal tract

- gastropod

- gastrotrich

- gastrula

- gas-turbine engine

- Gatchina

- gate

- gateleg table

- Gates, Bill

- Gates, Frederick T.

- Gateshead

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr.

- Gates, Horatio

- Gates, John Warne

- Gates, Melinda

- Gates of Paradise

- Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve

- Gates, Robert M.

- Gate Theatre

- Gath

- Gatineau

- Gatineau River