smallpox

disease

Introduction

also called variola major

acute infectious disease that begins with a high fever, headache, and back pain and then proceeds to an eruption on the skin that leaves the face and limbs covered with cratered pockmarks, or pox. For centuries smallpox was one of the world's most dreaded plagues (epidemic), killing as many as 30 percent of its victims, most of them children. Those who survived were permanently immune to a second infection, but they faced a lifetime of disfigurement and in some cases blindness. But smallpox was also one of the first diseases to be controlled by a vaccine, particularly following the great experiments of the English physician Edward Jenner (Jenner, Edward) in 1796. In 1967 the World Health Organization (WHO) began a global vaccination program against smallpox, and in 1980 the disease was officially declared eradicated.

History

Smallpox is caused by infection with variola major, a virus of the family Poxviridae. (A less-virulent form of smallpox, called alastrim, is caused by a closely related virus known as variola minor.) There are no natural animal carriers or natural propagation of variola outside the human body. The disease is thought by some scholars to have arisen among settled agricultural populations in Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia, history of) as early as the 5th millennium BC and in the Nile River valley in the 3rd millennium BC. The mummified body of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses V (died c. 1156 BC) bears evidence of pustules characteristic of smallpox. It is possible that smallpox was behind the great plague of Athens in 430 BC, recorded by the Greek historian Thucydides, and a devastating plague carried to Italy by a Roman army returning from Mesopotamia around AD 165. Smallpox is assumed to have been endemic in (that is, originating within) the Ganges River basin in India by the 1st millennium BC; the earliest likely references to the disease occur in the Caraka-saṃhitā and Suśruta-saṃhitā, medical works compiled by the first centuries of the Common Era. By the 2nd century AD, smallpox was endemic in the Huang Ho (Huang He) and Yangtze River valleys of China, the disease being distinctly described by the alchemist Ko Hung around 340. Smallpox appeared in North Africa and southern Europe following the Moorish conquests of the 8th century, and after the Crusade (Crusades)s it appeared sporadically throughout Europe. Possibly as early as the 12th century, Arab and Indian traders took the disease to the coast of East Africa, and Muslim caravaners and pilgrims crossing the Sahara Desert took it to West Africa as well.

It is difficult to discern from early writings whether people were able to distinguish smallpox from other diseases. The most reliable early account comes from the Persian physician ar-Rāzī (Rāzī, ar-), c. AD 900. Ar-Rāzī, known as Rhazes to his European translators, clearly described the symptoms of smallpox and distinguished it from measles. Around 570, Bishop Marius of Avicentum (near Lausanne, Switzerland) had introduced the Latin term variola (meaning “pox” or “pustule”) to describe diseases that may have included smallpox. The English term pox was used to describe various eruptive diseases, including smallpox, but it was not until the 16th century that variola became popularly known as the “small pox,” to distinguish it from syphilis (the “Great Pox”). By that time smallpox seems to have succeeded plague as the most feared pestilence in Europe. A huge pandemic reached from Europe to the Middle East in 1614, and epidemics arose regularly in Europe throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. There were frequent outbreaks in the American colonies and in British India as well. Introduced to the Americas by European conquerors and settlers, smallpox decimated native populations from the Plains Indians (Plains Indian) of Canada and the United States to the Aztecs (Aztec) of Mexico and the Araucanians of Chile. The Australian Aboriginals (Australian Aborigine) also suffered large losses from the disease in the 19th century.

Though medical science had not yet grasped the concept of infectious organisms such as viruses, it was understood that smallpox was somehow a contagious disease and that its victims had to be separated from the general populace. Little could be done for the victims. The first edition of Encyclopædia Britannica (1768) repeats the general approach of the great 17th-century English physician Thomas Sydenham (Sydenham, Thomas), which included procedures such as bloodletting, induction of vomiting, and administration of enemas in order to “keep the inflammation of the blood within due bounds.” In all parts of the world, smallpox outbreaks brought on desperate pleas by believers for divine assistance in lifting the scourge. Beyond that, the only hope lay in preventing outbreaks from occurring.

In southwestern Asia it had been known for centuries that a healthy person could be made immune to smallpox by being injected with pus taken from the sores of an infected person. Another technique, practiced in China, was to grind the scabs of a smallpox victim and blow the powder through a tube into the nose of a healthy person. People inoculated in this way would suffer a brief illness themselves and would be contagious for a period, and a few would contract a serious infection and die; but the risk of dying was far less than in a smallpox epidemic (roughly 2 percent, compared with 20 to 30 percent), and the benefit of immunity was clear. In the early 18th century several European doctors and, most prominently, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley), the wife of Britain's ambassador to Turkey, began to publicize the value of inoculation (or variolation, as it came to be known), and the practice was soon adopted by royalty and people of means in Europe and America. However, the procedure was expensive and difficult, and it had little influence beyond the well-to-do classes and certain military forces.

A much safer procedure was developed by Edward Jenner (Jenner, Edward), a physician in Gloucestershire, England. In 1796 Jenner deliberately infected a small boy with variolae vaccinae, or cowpox, a bovine version of smallpox. The boy suffered only a mild noncontagious reaction and then showed no reaction to a subsequent inoculation with variola major. The superiority of vaccination (vaccine), as this technique came to be known, was immediately recognized. During the 19th century, vaccination programs, many of them compulsory, were instituted in many countries. At first vaccine was obtained directly from vaccinated persons, but soon it was being commercially harvested from pustules grown on the skin of inoculated calves. Later in the century it became apparent that the cowpox virus had been supplanted in vaccines by a different strain. It is still not certain whether the new virus, called vaccinia, was a mutation of cowpox virus or a completely separate strain, but it remains the virus used for vaccine production to this day.

A much safer procedure was developed by Edward Jenner (Jenner, Edward), a physician in Gloucestershire, England. In 1796 Jenner deliberately infected a small boy with variolae vaccinae, or cowpox, a bovine version of smallpox. The boy suffered only a mild noncontagious reaction and then showed no reaction to a subsequent inoculation with variola major. The superiority of vaccination (vaccine), as this technique came to be known, was immediately recognized. During the 19th century, vaccination programs, many of them compulsory, were instituted in many countries. At first vaccine was obtained directly from vaccinated persons, but soon it was being commercially harvested from pustules grown on the skin of inoculated calves. Later in the century it became apparent that the cowpox virus had been supplanted in vaccines by a different strain. It is still not certain whether the new virus, called vaccinia, was a mutation of cowpox virus or a completely separate strain, but it remains the virus used for vaccine production to this day.

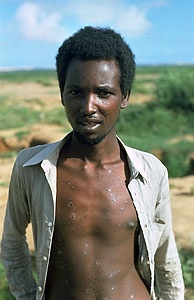

By the beginning of the 20th century, smallpox was no longer endemic in several countries of continental Europe. Endemic smallpox was eradicated from the United Kingdom in 1934, the U.S.S.R. in 1936, Canada in 1946, the United States in 1949, Japan in 1951, and China in 1961. Still, in an age of global travel only an international effort could completely eradicate the disease. In 1967 WHO began to vaccinate entire populations around every reported outbreak of smallpox. The disease was no longer endemic in India by 1975 and in Ethiopia by 1976. The last endemic case of smallpox (actually an infection of variola minor) was recorded in Somalia in 1977. No cases were reported from 1977 to 1980, with the exception of two cases in England in 1978 whose source was in a laboratory, and in 1980 the disease was declared exterminated.

By the beginning of the 20th century, smallpox was no longer endemic in several countries of continental Europe. Endemic smallpox was eradicated from the United Kingdom in 1934, the U.S.S.R. in 1936, Canada in 1946, the United States in 1949, Japan in 1951, and China in 1961. Still, in an age of global travel only an international effort could completely eradicate the disease. In 1967 WHO began to vaccinate entire populations around every reported outbreak of smallpox. The disease was no longer endemic in India by 1975 and in Ethiopia by 1976. The last endemic case of smallpox (actually an infection of variola minor) was recorded in Somalia in 1977. No cases were reported from 1977 to 1980, with the exception of two cases in England in 1978 whose source was in a laboratory, and in 1980 the disease was declared exterminated.With the disappearance of the global threat, there was less incentive for prevention. In the United States, routine vaccination already had been discontinued in 1971, and production of vaccine was suspended in 1982. Stocks of variola major were kept in only two countries, the United States and Russia, which had cultivated the virus as part of their biological weapons (biological weapon) programs during the Cold War. At the beginning of the 21st century, the increasing sophistication and viciousness of international terrorist groups raised concerns that entire populations were now vulnerable to deliberate infestation. In response, many countries began to produce and store fresh stocks of vaccine for use in emergencies.

In 2007 the Food and Drug Administration in the United States approved a new smallpox vaccine, the only new vaccine for smallpox to be approved since 1931. The new vaccine, called ACAM2000, is produced using basic cell-culture techniques that allow it to be made quickly and in sufficient quantity in the event of a national smallpox emergency.

The course of the disease

Each case of smallpox arose from close contact with another case of the disease, usually by inhalation of virus that had been expelled in the breath or saliva droplets of an infected person. Despite the hardiness of the variola virus, smallpox was not a highly infectious disease; infected persons usually did not infect more than two to five of their closest contacts. The great danger from the disease was that it could cause only a very mild attack in vaccinated persons, yet these persons could unwittingly spread the fatal form of the disease. It was therefore essential in dealing with an outbreak to make thorough enquiry into all possible contacts of patients and to follow these contacts and either ascertain that they had escaped infection or else isolate them at once if they showed any sign of infection.

Once variola major entered the body through the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract, there was a one- to two-week incubation period during which the person showed no signs of infection. The virus multiplied in the lymph nodes, spleen, and bone marrow, then migrated in white blood cells to small blood vessels near the surface of the skin. Illness first became apparent with a sudden high fever of 38.5 to 40.5 °C (101 to 105 °F), severe headache and back pain, and sometimes abdominal pain and vomiting. Two to five days later these flulike symptoms abated. However, they were followed by the appearance of lesions in the mouth and by a rash on the skin that was heaviest on the face and lower part of the limbs, displaying what was called a centrifugal, or centre-fleeing, distribution. The rash might be so profuse as to be confluent, especially on the face, or so scanty that the lesions were missed altogether. The first manifestation of the rash was a flat spot, or macule, which over the next few days changed into a raised papule, then into a clear blister, or vesicle, and finally into an infected pustule. By this time the fever usually returned. In fatal cases, death frequently came after a week or two of illness, brought on by the toxic effects of huge quantities of virus in the blood and the inflammatory response of the body's immune system. In nonfatal cases, the pustules dried up and formed scabs that, upon separation, left multiple pockmarked scars.

In some cases there was a toxic eruption during the initial fever, before the appearance of the true smallpox rash. These toxic rashes might be diffuse blushes on trunk or limbs, somewhat suggestive of scarlet fever or measles; they might, on the other hand, be deeper red, with small hemorrhages like fleabites or larger blotches in the skin. The first type of rash was clinically unimportant, but the deep red, hemorrhagic rash occurred in the most severe, usually fatal cases of the disease. Frequently such patients died before the true smallpox rash had time to develop, and the disease was not diagnosed. These cases were not usually sources of infection, however, because smallpox was not infectious until the characteristic focal eruption had come out in the throat and on the skin.

If smallpox vaccine was given within a few days of exposure to the virus, it would act to prevent illness or lessen the degree of symptoms. However, once symptoms appeared, treatment was limited. The patient was kept as clean and comfortable as possible, the fever was treated with analgesics, and pustules were treated with antiseptics to prevent secondary infection.

- Médoc

- Médéa

- Méhul, Étienne-Nicolas

- Mékambo

- Méline, Félix-Jules

- Méliès, Georges

- mélodie

- Ménage, Gilles

- Ménard, Louis-Nicolas

- Méndez, Aparicio

- Ménière disease

- Mérida

- Mérida, Carlos

- Mérimée, Prosper

- Méryon, Charles

- métayage

- Métis

- Métraux, Alfred

- México

- Mézières, Philippe de

- mêlée

- Míkonos

- Móricz, Zsigmond

- Mór Jókai

- Môle Saint-Nicolas