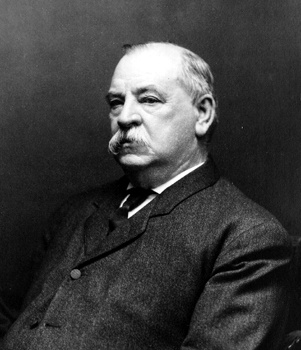

Cleveland, Grover

president of United States

in full Stephen Grover Cleveland

born March 18, 1837, Caldwell, New Jersey, U.S.

died June 24, 1908, Princeton, New Jersey

22nd and 24th president of the United States (1885–89 and 1893–97) and the only president ever to serve two discontinuous terms. Cleveland distinguished himself as one of the few truly honest and principled politicians of the Gilded Age. His view of the president's function as primarily that of blocking legislative excesses made him quite popular during his first term, but that view cost him public support during his second term when he steadfastly denied a positive role for government in dealing with the worst economic collapse the nation had yet faced. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)

22nd and 24th president of the United States (1885–89 and 1893–97) and the only president ever to serve two discontinuous terms. Cleveland distinguished himself as one of the few truly honest and principled politicians of the Gilded Age. His view of the president's function as primarily that of blocking legislative excesses made him quite popular during his first term, but that view cost him public support during his second term when he steadfastly denied a positive role for government in dealing with the worst economic collapse the nation had yet faced. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)Cleveland was the son of Richard Falley Cleveland, an itinerant Presbyterian minister, and Ann Neal. The death of Grover Cleveland's father in 1853 forced him to abandon school in order to support his mother and sisters. After clerking in a law firm in Buffalo, New York, he was admitted to the bar in 1859 and soon entered politics as a member of the Democratic Party. During the Civil War (American Civil War) he was drafted but hired a substitute so that he could care for his mother—an altogether legal procedure but one that would make him vulnerable to political attack in the future. In 1863 he became assistant district attorney of Erie county, New York, and in 1870–73 he served as county sheriff. With this slight political background and only modest success as a lawyer, the apparently unambitious Buffalo attorney launched perhaps the most meteoric rise in American politics.

In 1881, eight years after stepping down as sheriff, Cleveland was nominated for mayor by Buffalo Democrats who remembered his honest and efficient service in that office. He won the election easily. As Buffalo's chief executive he became known as the “veto mayor” for his rejection of spending measures he considered to be wasteful and corrupt. In 1882, without the support of the Tammany Hall Democratic machine in New York City, Cleveland received his party's nomination for governor, and he went on to crush his Republican opponent by more than 200,000 votes.

As governor of New York, Cleveland again used the veto frequently, even to turn down measures that enjoyed wide public support. His devotion to principle and his unstinting opposition to Tammany Hall soon earned him a national reputation—particularly among Americans disgusted with the frequent scandals of Gilded Age politics.

As governor of New York, Cleveland again used the veto frequently, even to turn down measures that enjoyed wide public support. His devotion to principle and his unstinting opposition to Tammany Hall soon earned him a national reputation—particularly among Americans disgusted with the frequent scandals of Gilded Age politics.In 1884 the Democrats sought a presidential candidate who would contrast sharply with Republican nominee James G. Blaine (Blaine, James G.), a longtime Washington insider whose reputation for dishonesty and financial impropriety prompted the Republican Mugwump faction to bolt their party. Cleveland's image was the opposite of Blaine's, and he seemed likely to draw Mugwump votes to the Democratic ticket. As a result, Cleveland won the Democratic nomination with ease.

Cabinet of President Grover ClevelandDuring the campaign, Cleveland's image as the clean alternative to the supposedly sullied Blaine suffered serious damage when Republicans charged that the Democratic candidate had fathered a child out of wedlock some 10 years earlier. As Republicans joyously chortled, “Ma, ma, where's my pa?,” Cleveland remained undaunted, and he instructed Democratic leaders to “Tell the truth.” The truth, as Cleveland admitted, was that he had had an affair with the child's mother, Maria Halpin, and had agreed to provide financial support when she named him as the father, though he was uncertain whether the child was really his. Meanwhile, Democrats, trying to contrast Cleveland's reputation with Blaine's, chanted “Blaine Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine!” Late in the campaign, Blaine experienced an embarrassment of his own, when a supporter at a rally in New York City described the Democrats as the party of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion”—a swipe at the city's Irish Catholics, many of whom Blaine hoped to lure into his camp. Although Blaine was present when the fateful words were spoken, he did nothing to dissociate himself from the remark. The general election was determined by electoral votes from New York state, which Blaine lost to Cleveland by fewer than 1,200 votes. (See primary source document: First Inaugural Address (Grover Cleveland: First Inaugural Address). See also Cabinet of President Grover Cleveland.)

Cabinet of President Grover ClevelandDuring the campaign, Cleveland's image as the clean alternative to the supposedly sullied Blaine suffered serious damage when Republicans charged that the Democratic candidate had fathered a child out of wedlock some 10 years earlier. As Republicans joyously chortled, “Ma, ma, where's my pa?,” Cleveland remained undaunted, and he instructed Democratic leaders to “Tell the truth.” The truth, as Cleveland admitted, was that he had had an affair with the child's mother, Maria Halpin, and had agreed to provide financial support when she named him as the father, though he was uncertain whether the child was really his. Meanwhile, Democrats, trying to contrast Cleveland's reputation with Blaine's, chanted “Blaine Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine!” Late in the campaign, Blaine experienced an embarrassment of his own, when a supporter at a rally in New York City described the Democrats as the party of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion”—a swipe at the city's Irish Catholics, many of whom Blaine hoped to lure into his camp. Although Blaine was present when the fateful words were spoken, he did nothing to dissociate himself from the remark. The general election was determined by electoral votes from New York state, which Blaine lost to Cleveland by fewer than 1,200 votes. (See primary source document: First Inaugural Address (Grover Cleveland: First Inaugural Address). See also Cabinet of President Grover Cleveland.) As president, Cleveland continued to act in the same negative capacity that had marked his tenures as mayor and governor. He nullified fraudulent grants to some 80,000,000 acres (30,000,000 hectares) of Western public lands and vetoed hundreds of pension bills that would have sent federal funds to undeserving Civil War veterans. Once again, Cleveland's rejection of wasteful and corrupt measures endeared the president to citizens who admired his honesty and courage. He also received credit for two of the more significant measures enacted by the federal government in the 1880s: the Interstate Commerce Act (1887), which established the Interstate Commerce Commission, the first regulatory agency in the United States, and the Dawes General Allotment Act (1887), which redistributed Indian reservation land to individual tribe members.

As president, Cleveland continued to act in the same negative capacity that had marked his tenures as mayor and governor. He nullified fraudulent grants to some 80,000,000 acres (30,000,000 hectares) of Western public lands and vetoed hundreds of pension bills that would have sent federal funds to undeserving Civil War veterans. Once again, Cleveland's rejection of wasteful and corrupt measures endeared the president to citizens who admired his honesty and courage. He also received credit for two of the more significant measures enacted by the federal government in the 1880s: the Interstate Commerce Act (1887), which established the Interstate Commerce Commission, the first regulatory agency in the United States, and the Dawes General Allotment Act (1887), which redistributed Indian reservation land to individual tribe members.In 1886 Cleveland, a lifelong bachelor, married Frances Folsom, the daughter of his former law partner. Frances Cleveland (Cleveland, Frances), 27 years younger than her husband, proved to be a very popular first lady. To all appearances the marriage was a happy one, though during the 1888 presidential campaign she was forced to publicly refute Republican-spread rumours that Cleveland had beaten her during drunken rages.

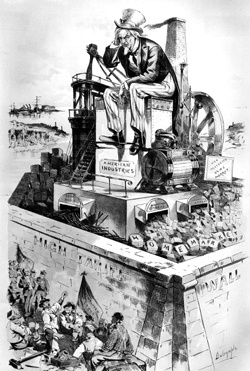

The major issue of the 1888 presidential campaign was the protective tariff. Cleveland, running for reelection, opposed the high tariff, calling it unnecessary taxation imposed upon American consumers, while Republican candidate Benjamin Harrison (Harrison, Benjamin) defended protectionism. On election day, Cleveland won about 100,000 more popular votes than Harrison, evidence of the esteem in which the president was held and to the widespread desire for a lower tariff. Yet Harrison won the election by capturing a majority of votes in the electoral college (233 to 168), largely as a result of lavish campaign contributions from pro-tariff business interests in the crucial states of New York and Indiana.

The major issue of the 1888 presidential campaign was the protective tariff. Cleveland, running for reelection, opposed the high tariff, calling it unnecessary taxation imposed upon American consumers, while Republican candidate Benjamin Harrison (Harrison, Benjamin) defended protectionism. On election day, Cleveland won about 100,000 more popular votes than Harrison, evidence of the esteem in which the president was held and to the widespread desire for a lower tariff. Yet Harrison won the election by capturing a majority of votes in the electoral college (233 to 168), largely as a result of lavish campaign contributions from pro-tariff business interests in the crucial states of New York and Indiana. Cleveland spent the four years of the Harrison presidency in New York City, working for a prominent law firm. When the Republican-dominated Congress and the Harrison administration enacted the very high McKinley Tariff in 1890 and made the surplus in the treasury vanish in a massive spending spree, the path to a Democratic victory in 1892 seemed clear. Cleveland won his party's nomination for the third consecutive time and then soundly defeated Harrison and Populist Party candidate James B. Weaver (Weaver, James B) by 257 electoral votes to Harrison's 145, making Cleveland the only president ever elected to discontinuous terms. (See primary source document: Second Inaugural Address (Grover Cleveland: Second Inaugural Address).)

Cleveland spent the four years of the Harrison presidency in New York City, working for a prominent law firm. When the Republican-dominated Congress and the Harrison administration enacted the very high McKinley Tariff in 1890 and made the surplus in the treasury vanish in a massive spending spree, the path to a Democratic victory in 1892 seemed clear. Cleveland won his party's nomination for the third consecutive time and then soundly defeated Harrison and Populist Party candidate James B. Weaver (Weaver, James B) by 257 electoral votes to Harrison's 145, making Cleveland the only president ever elected to discontinuous terms. (See primary source document: Second Inaugural Address (Grover Cleveland: Second Inaugural Address).)Early in Cleveland's second term the United States sank into the most severe economic depression the country had yet experienced. Cleveland believed that the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890—which required the secretary of the treasury to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver each month—had eroded confidence in the stability of the currency and was thus at the root of the nation's economic troubles. He called Congress into special session and, over considerable opposition from Southern and Western members of his own party, forced the repeal of the act (see primary source document: Against a Free Silver Policy (Grover Cleveland: Against a Free Silver Policy)). Yet the depression only worsened, and Cleveland's negative view of government began to diminish his popularity. Apart from assuring a sound—i.e., gold-backed—currency, he insisted the government could do nothing to alleviate the suffering of the many thousands of people who had lost jobs, homes, and farms. His popularity sank even lower when—distraught over the diminishing quantity of gold in the treasury—he negotiated with a syndicate of bankers headed by John Pierpont Morgan (Morgan, John Pierpont) to sell government bonds abroad for gold. The deal succeeded in replenishing the government's gold supply, but the alliance between the president and one of the era's leading “robber barons” intensified the feeling that Cleveland had lost touch with ordinary Americans.

That the president cared more about the interests of big business than those of ordinary Americans seemed manifest in Cleveland's handling of the Pullman Strike in 1894. Cleveland sent federal troops to Chicago to quell violence at Pullman's railroad car facility, despite the objections of Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld (Altgeld, John Peter). The strike was broken within a week, and the president received the plaudits of the business community. However, he had severed whatever support he still had in the ranks of labour.

In foreign policy Cleveland displayed the same courageous righteousness that characterized much of his domestic policy. He withdrew from the Senate a treaty for the annexation of Hawaii when he learned how the Hawaiian leader, Queen Liliuokalani, had been overthrown in an American-led coup. He also refused to be swept along with popular sentiment for intervention on behalf of Cuban insurgents fighting for independence from Spain (see primary source document: American Interest in the Cuban Revolution (Grover Cleveland: American Interest in the Cuban Revolution)). Yet he was not totally immune to the new spirit of American assertiveness on the international stage. By invoking the Monroe Doctrine, for example, he forced Britain to accept arbitration of a boundary dispute between its colony of British Guiana (now Guyana) and neighbouring Venezuela.

At the tumultuous Democratic convention in 1896, the party was divided between supporters of Cleveland and the gold standard and those who wanted a bimetallic standard of gold and silver designed to expand the nation's money supply. When William Jennings Bryan (Bryan, William Jennings) delivered his impassioned Cross of Gold speech, the delegates not only nominated the little-known Bryan for president but also repudiated Cleveland—the first and only president ever to be so repudiated by his own party.

Cleveland retired to Princeton, New Jersey, where he became active in the affairs of Princeton University as a lecturer in public affairs and as a trustee (1901–08). As the rancour over the gold standard subsided with the return of prosperity, Cleveland regained much of the public admiration he had earlier enjoyed. Never again, however, would the Democratic Party adhere to the pro-business, limited-government views that so dominated his presidency, and Cleveland remains the most conservative Democrat to have occupied the White House since the Civil War.

Additional Reading

A collection of Cleveland's documents and speeches can be found in George F. Parker (compiler and ed.), The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland (1892, reprinted 1970). Most of his important surviving letters are available in Allan Nevins (compiler and ed.), Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908 (1933, reprinted 1970).Biographies include Allan Nevins, Grover Cleveland (1932); Horace Samuel Merrill, Bourbon Leader: Grover Cleveland and the Democratic Party, ed. by Oscar Handlin (1957); and Rexford G. Tugwell, Grover Cleveland (1968). Cleveland's place in the Democratic Party is explored in J. Rogers Hollingsworth, The Whirligig of Politics: The Democracy of Cleveland and Bryan (1963), focusing on the beginning of Cleveland's second term through the 1904 presidential elections. Richard E. Welch, Jr., The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (1988), analyzes his two terms in office. John F. Marszalek, Grover Cleveland: A Bibliography (1988), is a useful resource comprising over 1,800 annotated entries.

- Allgood, Sara

- Alliaceae

- Alliance

- alliance

- Alliance for Progress

- Alliance Israélite Universelle

- Alliance Party of Northern Ireland

- Allied air strength, September 1939

- Allied Powers

- AlliedSignal

- Allier River

- alligator

- alligator apple

- alligator lizard

- Alligator Rivers

- Alliluyeva, Svetlana

- All-India Trade Union Congress

- Allingham, Margery

- All in the Family

- Allison, William B.

- alliteration

- alliterative prose

- alliterative verse

- allium

- Allman Brothers Band, the