Southwest Indian

people

Introduction

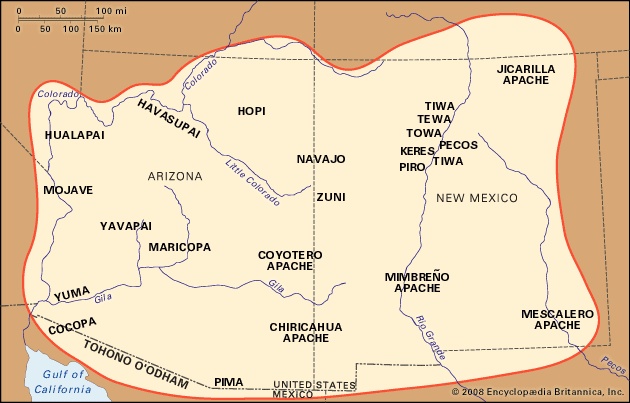

member of any of the Native American peoples inhabiting the southwestern United States; some scholars also include the peoples of northwestern Mexico in this culture area. More than 20 percent of Native Americans in the United States live in this region, principally in the present-day states of Arizona and New Mexico.

member of any of the Native American peoples inhabiting the southwestern United States; some scholars also include the peoples of northwestern Mexico in this culture area. More than 20 percent of Native Americans in the United States live in this region, principally in the present-day states of Arizona and New Mexico.The Southwest culture area is located between the Rocky Mountains and the Mexican Sierra Madre. The Continental Divide separates the landscape into the watersheds of two great river systems: the Colorado–Gila–San Juan, in the west, and the Rio Grande–Pecos, in the east. The environment is arid, with some areas averaging less than 4 inches (10 cm) of precipitation each year; droughts are common. Despite its low moisture content, coarse texture, and occasional salty patches, the soil of most of the Southwest is relatively fertile.

The distribution of resources in the region is determined more by elevation than by latitude. The predominant landscape feature in the north is the Colorado Plateau, a cool, arid plain into which the Colorado and Rio Grande systems have carved deep canyons. Precipitation tends to be greater at the plateau's higher elevations, which support scrub and piñon-juniper woodland, rattlesnakes, rabbits, coyotes, bobcats, and mule deer. At lower elevations the plateau also supports grasses and antelope. To the south the river systems descend from the plateau, and canyons, mesas, and steep escarpments give way to a basin and range system. River valleys here support clusters of cottonwood, willow, mesquite, and sycamore trees, and mule deer, fish, and waterfowl. The areas away from the rivers are characterized by desert flora and fauna, including mesquite, creosote bush, cactus, yucca, small mammals, and reptiles.

Traditional culture patterns

The people of the Cochise culture were among the earliest residents of the Southwest. A desert-adapted hunting and gathering culture whose diet emphasized plant foods and small game, this group lived in the region as early as c. 7000 BC.

Farming became important for subsequent residents including the Ancestral Pueblo (Ancestral Pueblo culture) (Anasazi; c. AD 100–1600), the Mogollon (Mogollon culture) (c. AD 200–1450), and the Hohokam (Hohokam culture) (c. AD 200–1400). These groups lived in permanent and semipermanent settlements that they sometimes built near (or even on) sheltering cliffs; developed various forms of irrigation; grew crops of corn (maize), beans, and squash; and had complex social and ritual habits. It is believed that the Ancestral Pueblo were the ancestors of the modern Pueblo Indians, that the Hohokam were the ancestors of the Pima and Tohono O'odham (Papago), and that the Mogollon dispersed or joined other communities. See also Native American: Prehistory (Native American).

Farming became important for subsequent residents including the Ancestral Pueblo (Ancestral Pueblo culture) (Anasazi; c. AD 100–1600), the Mogollon (Mogollon culture) (c. AD 200–1450), and the Hohokam (Hohokam culture) (c. AD 200–1400). These groups lived in permanent and semipermanent settlements that they sometimes built near (or even on) sheltering cliffs; developed various forms of irrigation; grew crops of corn (maize), beans, and squash; and had complex social and ritual habits. It is believed that the Ancestral Pueblo were the ancestors of the modern Pueblo Indians, that the Hohokam were the ancestors of the Pima and Tohono O'odham (Papago), and that the Mogollon dispersed or joined other communities. See also Native American: Prehistory (Native American).Language

The Southwest was home to representatives from several North American Indian language (North American Indian languages) families, including Hokan, Uto-Aztecan, Tanoan, Keresan, Kiowa-Tanoan, Penutian, and Athabaskan.

The Hokan (Hokan languages)-speaking Yuman peoples were the westernmost residents of the region; they lived in the river valleys and the higher elevations of the basin and range system there. The so-called River Yumans, including the Quechan (Yuma), Mojave, Cocopa, and Maricopa, resided on the Lower Colorado and the Gila River; their cultures combined some traditions of the Southwest culture area with others of the California Indians (California Indian). The Upland Yumans, including the Havasupai, Hualapai, and Yavapai, lived on secondary and ephemeral streams in the western basins and ranges.

Two groups that spoke Uto-Aztecan languages resided in the southwestern portion of the culture area, near the border between the present-day states of Arizona (U.S.) and Sonora (Mex.). The Tohono O'odham were located west of the Santa Cruz River. The closely related Pima lived along the middle Gila River.

The Pueblo Indians were linguistically diverse. Those living along the Rio Grande and its tributaries are generally referred to as the eastern Pueblos, while those on the Colorado Plateau are assigned to the western division. The eastern group included the Keresan-speaking Zia, Santa Ana, San Felipe, Santo Domingo, and Cochiti, and representatives of three members of the Kiowa-Tanoan language family: the Tewa-speaking San Ildefonso, San Juan, Santa Clara, Tesuque, and Nambe; the Tiwa-speaking Isleta, Sandia, Taos, and Picuris; and the Towa-speaking Jemez. The western Pueblo tribes included the Hopi (Uto-Aztecan; see also Hopi language), Hano (Tanoan), Zuni (Penutian), and Acoma and Laguna (Keresan).

The Navajo and the closely related Apache spoke Athabaskan languages (Athabaskan language family). The Navajo lived on the Colorado Plateau near the Hopi villages. The Apache traditionally resided in the range and basin systems south of the plateau. The major Apache tribes included the Western Apache, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla (Jicarilla Apache), Lipan, and Kiowa Apache. The Athabaskan-speaking groups migrated from northwestern North America to the Southwest and probably did not reach the area until sometime between AD 1100 and 1500.

Subsistence, settlement patterns, and social organization

Most peoples of the Southwest engaged in both farming and hunting and gathering; the degree to which a given culture relied upon domesticated or wild foods was primarily a matter of the group's proximity to water. A number of domesticated resources were more or less ubiquitous throughout the culture area, including corn (maize), beans, squash, cotton, turkeys, and dogs. During the period of Spanish colonization, horses, burros, and sheep were added to the agricultural repertoire, as were new varieties of beans, plus wheat, melons, apricots, peaches, and other cultigens.

Most groups coped with the desert environment by occupying sites on waterways; these ranged in quality and reliability from large permanent rivers such as the Colorado, through secondary streams, to washes or gullies that channeled seasonal rainfall but were dry most of the year. Precipitation was unpredictable and fell in just a few major rains each year, compelling many groups to engage in irrigation. While settlements along major waterways could rely almost entirely on agriculture for food, groups whose access was limited to ephemeral waterways typically used farming to supplement hunting and gathering, relying on wild foods during much of the year.

The Yumans, (Yuman) Pima, and Tohono O'odham

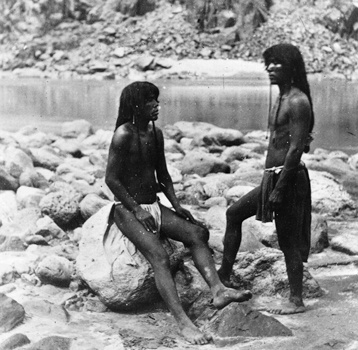

The western and southern reaches of the culture area were home to the Hokan-speaking Yuman groups and the Uto-Aztecan-speaking Pima and Tohono O'odham. These peoples shared a number of cultural features, principally in terms of kinship and social organization, although their specific subsistence strategies represented a continuum from full-time agriculture to full-time foraging.

kinship was usually reckoned bilaterally, through both the male and female lines. For those groups that raised crops, the male line was somewhat privileged as fields were commonly passed from father to son. Most couples chose to reside near the husband's family (patrilocality), and clan membership was patrilineal. In general women were responsible for most domestic tasks, such as food preparation and child-rearing, while male tasks included the clearing of fields and hunting.

The most important social unit was the extended family, a group of related individuals who lived and worked together; groups of families living in a given locale formed bands (band). Typically the male head of each family participated in an informal band council that settled disputes (often over land ownership, among the farming groups) and made decisions regarding community problems. Band leadership accrued to those with proven skills in activities such as farming, hunting, and consensus-building. A number of bands constituted the tribe. Tribes were usually organized quite loosely—the Pima were the only group with a formally elected tribal chief—but were politically important as the unit that determined whether relations with neighbouring groups were harmonious or agitated. Among the Yumans, the tribe provided the people with a strong ethnic identity, although in other cases most individuals identified more strongly with the family or band.

The most desirable bottomlands along the Colorado and Gila rivers were densely settled by the so-called River Yumans, including the Mojave, Quechan, Cocopa, and Maricopa. They lived in riverside hamlets and their dwellings included houses made of log frameworks covered with sand, brush, or wattle-and-daub (wattle and daub). The rivers provided plentiful water despite a minimum of rainfall and the hot desert climate. Overflowing their banks each spring, they provided fresh silt and moisture to small, irregular fields where people cultivated several varieties of corn as well as beans, pumpkins, melons, and grasses. Abundant harvests were supplemented with wild fruits and seeds, fish, and small game.

The most desirable bottomlands along the Colorado and Gila rivers were densely settled by the so-called River Yumans, including the Mojave, Quechan, Cocopa, and Maricopa. They lived in riverside hamlets and their dwellings included houses made of log frameworks covered with sand, brush, or wattle-and-daub (wattle and daub). The rivers provided plentiful water despite a minimum of rainfall and the hot desert climate. Overflowing their banks each spring, they provided fresh silt and moisture to small, irregular fields where people cultivated several varieties of corn as well as beans, pumpkins, melons, and grasses. Abundant harvests were supplemented with wild fruits and seeds, fish, and small game.The Upland Yumans (including the Hualapai, Havasupai, and Yavapai), the Pima, and the Tohono O'odham lived on the Gila and Salt rivers, along smaller streams, and along seasonal waterways. The degree to which they relied upon agriculture depended upon their distance from permanently flowing water. Those who lived near such waterways built stone canals with which they irrigated fields of corn, beans, and squash. Those with no permanently flowing water planted crops in the alluvial fans at the mouths of washes and built low walls or check dams to slow the torrents caused by brief but intense summer rains. These latter groups relied more extensively on wild foods than on agriculture; some engaged in no agriculture whatsoever, instead living in a fashion similar to the Great Basin Indians (Great Basin Indian).

Upland settlement patterns also reflected differential access to water. Hamlets near permanent streams were occupied all year and included dome-shaped houses with walls and roofs of wattle-and-daub or thatch. The groups that relied on ephemeral streams divided their time between summer settlements near their crops and dry-season camps at higher elevations where fresh water and game were more readily available. Summer residences were usually dome-shaped and built of thatch, while lean-tos and windbreaks served as shelter during the rest of the year.

The Pueblos (Pueblo Indians)

Traditional social and religious practices are fairly well understood for the western Pueblo peoples because distance and the rugged landscape of the Colorado Plateau afforded them some protection from the depredations of Spanish, and later American, colonizers. Less is known of the pre-conquest practices of the eastern Pueblos. Their location on the banks of the Rio Grande made them easily accessible to colonizers, whose approaches to assimilation were often brutal. Many Pueblos, both eastern and western, took their traditional practices underground during the colonial period in order to avoid persecution; to a great extent they continue to protect their traditional cultures with silence. Their secret societies, each of which had a specific theme such as religion, war, policing, hunting, or healing, have proven quite difficult to investigate. Undoubtedly, however, they were and are important venues for social interaction and cultural transmission.

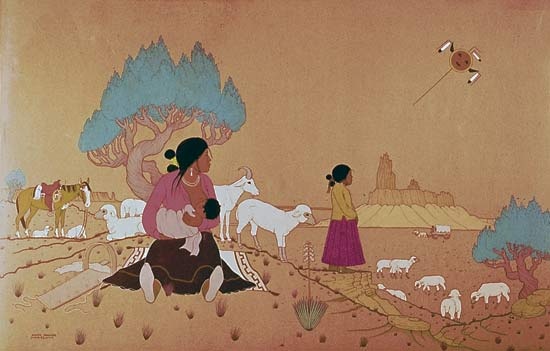

Traditional social and religious practices are fairly well understood for the western Pueblo peoples because distance and the rugged landscape of the Colorado Plateau afforded them some protection from the depredations of Spanish, and later American, colonizers. Less is known of the pre-conquest practices of the eastern Pueblos. Their location on the banks of the Rio Grande made them easily accessible to colonizers, whose approaches to assimilation were often brutal. Many Pueblos, both eastern and western, took their traditional practices underground during the colonial period in order to avoid persecution; to a great extent they continue to protect their traditional cultures with silence. Their secret societies, each of which had a specific theme such as religion, war, policing, hunting, or healing, have proven quite difficult to investigate. Undoubtedly, however, they were and are important venues for social interaction and cultural transmission. The Pueblo peoples lived in compact, permanent villages and resided in multifamily buildings (see pueblo architecture). The women of a household cared for young children; cultivated spring-irrigated gardens; produced fine baskets and pottery (Pueblo pottery); had charge of the preservation, storage, and cooking of food; and cared for certain clan fetishes (sacred objects carved of stone). The men of a household wove cloth, herded sheep, and raised field and dune crops of corn (maize), squash, beans, and cotton. A wide trade network brought materials such as turquoise, shell, copper, and macaw feathers to the Pueblo tribes; many of these exotic materials appear to have come from Mexico.

The Pueblo peoples lived in compact, permanent villages and resided in multifamily buildings (see pueblo architecture). The women of a household cared for young children; cultivated spring-irrigated gardens; produced fine baskets and pottery (Pueblo pottery); had charge of the preservation, storage, and cooking of food; and cared for certain clan fetishes (sacred objects carved of stone). The men of a household wove cloth, herded sheep, and raised field and dune crops of corn (maize), squash, beans, and cotton. A wide trade network brought materials such as turquoise, shell, copper, and macaw feathers to the Pueblo tribes; many of these exotic materials appear to have come from Mexico.The family was a key social grouping; extended family households of three generations were typical. The western Pueblos and the eastern Keresan-speaking groups reckoned kinship through the female line (matrilineally), while the remaining eastern Pueblos reckoned kinship patrilineally or bilaterally, through both parents. Residence usually coincided with kinship; among the matrilineal Zuni, for instance, a husband joined his wife's natal residence (matrilocality). A Zuni household would typically include a senior woman, her husband, and their unmarried children, plus the couple's married daughters, sons-in-law, and their children.

Related families formed a lineage, a kin group that could trace its ancestry directly to a known figure in the historical or legendary past. Lineages were often conceived of as timeless, extending backwards into the remote past and forward through generations yet unborn. Among the western Pueblo and the eastern Keresan-speakers, several related lineages were combined to form a clan; many villages had dozens of clans, which were often named for animals, plants, or other natural phenomena.

Instead of using clans, some Pueblos grouped lineages directly into two units called moieties. This was particularly prevalent among the eastern Pueblos, many of whom organized themselves into paired groups such as the “Squash People” and “Turquoise People” or the “Summer People” and “Winter People.”

Clans and moieties acted as corporate groups; they were responsible for sponsoring certain rituals and for organizing many aspects of community life. Among the matrilineal Hopi, for instance, each clan owned specific fields and ritual paraphernalia and the oldest active woman functioned as the clan's administrative leader. Her brother assumed the responsibilities of ceremonial leader, supervising annual reenactments of events that were part of clan history or tradition. At San Juan pueblo in the east, the kinship system was bilateral, and the fluidity inherent in a bilateral system was reflected in the moiety system as well: one was born into membership in one's father's moiety, but upon marriage a young woman became a member of her husband's division. At San Juan the leaders of the Summer and the Winter moieties were each responsible for village administration during their respective season (spring and summer were grouped together, as were autumn and winter). Many activities were limited to just one of the seasons; trading and hunting, for instance, could only take place under the authority of the Winter moiety, while the gathering of wild plants was limited to the period of the Summer People's administration.

Clan and moiety systems were important tools for managing the delegation of ritual and mundane tasks, but were also important in achieving harmony in other ways. Membership in these groups was symbolically extended to specific animals, plants, and other classes of natural and supernatural phenomena, metaphysically linking all aspects of the social, natural, and spiritual worlds together for a given tribe. In a concrete political sense, as well, the common (though not universal) custom of clan or moiety exogamy, or out-marriage, smoothed social relations by ensuring that households included members of different corporate groups.

The Navajo and Apache

While the peoples mentioned thus far all have very ancient roots in the Southwest, the Navajo and Apache are relative newcomers. Linguistic, archaeological, and historical evidence indicate that the ancestors of these groups were members of hunting-and-gathering cultures (hunting and gathering culture) that migrated to the region from present-day Canada, arriving by approximately AD 1500, although no earlier than AD 1100. The Navajo occupied a portion of the Colorado Plateau adjacent to Hopi lands. The Apache claimed the basin and range country east and south of the Plateau and surrounding the Rio Grande pueblos. Together, the Navajo and Apache are referred to as Apacheans.

By the early 17th century the Navajo and the Jicarilla (Jicarilla Apache), Lipan, and Western Apache had begun to engage in a relatively settled way of life, farming indigenous crops; after the advent of Spanish colonization, they incorporated new products such as sheep and cattle into their economies. The Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache continued to rely on hunting and gathering as the mainstay of their economies. All the groups raided the Pueblo tribes and later the Spanish and American colonizers. Raids were often (although not always) undertaken in stealth; the goal was generally to seize livestock and food stores rather than to engage in battle.

In general, Apachean women were responsible for raising their children; gathering and processing edible seeds and other wild plants, such as mescal, a cactus that provided food, juice, and fibres; collecting firewood and water; producing buckskin clothing, baskets, and pottery; and building the home. The Navajo were an exception to the last rule, as they viewed home construction as men's work. Apachean men hunted, fought, and raided. Among the more sedentary groups, women tended gardens, men tended fields, and both engaged in shepherding and weaving.

As their territories were generally unfavourable to the support of concentrated populations, the Apacheans tended to reside in dispersed groups. Although the Navajo and Western Apache had exogamous matrilineal clans, kinship was generally reckoned bilaterally and clans played little role among the other Apachean groups. The basic socioeconomic unit was the matrilocal extended family, a group of one or more related women, their husbands and unmarried sons, and their daughters, sons-in-law, and grandchildren. Within this group each nuclear family—or each wife and her children, if two or more women shared a husband—occupied a separate dwelling. Among the Navajo the preferred house form was the hogan, a circular lodge made of logs or stone and covered with a roof of earth; some hogans also had earth-berm walls. Among the Apache, the wickiup and tepee were used. The ramada, a freestanding rectangular arbour, was used by both groups for shade.

Among the Apache, a kin-based group of perhaps 20–30 individuals who lived and worked together constituted a band, the most important social group in daily life. Among the Navajo, similarly-sized “outfits,” or neighbouring extended families, cooperated in resolving issues such as range management and water use. Bands and outfits were organized under the direction of a leader chosen for his wisdom and previous success. They functioned on the basis of consensus, and individuals could, and often did, move to another group if they were uncomfortable with their current situation. A tribe comprised a group of bands that shared bonds of tradition, language, and culture; they were usually not formal political entities. The small bands that functioned as basic social units should not be confused with larger groups, such as the Mescalero, that are sometimes referred to as bands but are in fact tribes (see Sidebar: The Difference Between a Tribe and a Band).

Socialization and education

All of the Southwestern tribes viewed the raising of children as a serious adult responsibility. Most felt that each child had to be “made into” a member of the tribe and that adults had to engage in frequent self-reflection and redirection to remain a tribal member; in other words, ethnic identity was something that had to be achieved rather than taken for granted.

Children (infancy) were generally treated with warmth and permissiveness until they were weaned, a period that might last from one to three or four years. Care was taken not to agitate a child unduly: young children nursed on demand, and weaning and toilet training were gradual. Children were protected from harm through careful tending and by means of magical prophylactics. Cradles and cradleboards were used, especially during the first year of life; the Hopi viewed swaddling as the first of many periods of conditioning that helped the individual to gain self-control. From birth, children were treated as an integral part of the family; among the Navajo, for instance, the cradleboard was hung on a wall or pillar so that the child would be at eye level with others seated in the family circle.

Children (infancy) were generally treated with warmth and permissiveness until they were weaned, a period that might last from one to three or four years. Care was taken not to agitate a child unduly: young children nursed on demand, and weaning and toilet training were gradual. Children were protected from harm through careful tending and by means of magical prophylactics. Cradles and cradleboards were used, especially during the first year of life; the Hopi viewed swaddling as the first of many periods of conditioning that helped the individual to gain self-control. From birth, children were treated as an integral part of the family; among the Navajo, for instance, the cradleboard was hung on a wall or pillar so that the child would be at eye level with others seated in the family circle.From the beginning of childhood there was training in customary gender roles; little girls began to learn food processing and childcare, and little boys were given chores such as collecting firewood or tending animals. However, the most important work of childhood was the internalization of the abiding precept that individuals were expected to pull their own weight, at every age grade, according to their gender, strength, and talent.

When they were between five and seven years old, boys began to associate almost exclusively with the men of their households, who from then on directed their education into masculine tasks and lore. At about the same age, girls began to take on increasing responsibility for the exacting tasks of the household. Among the more nomadic groups, particularly the Apacheans, the physical strength, stoicism, and skill needed for battle were stressed, and training in the arts of war intensified as a youth grew to young manhood. Even among the more pacifist Pueblos, however, boys learned agility, endurance, and speed in running. Racing was important to the Pueblos because it was considered to possess magical efficacy in helping plants, animals, and human beings to grow.

Despite these similarities, tribes did show some marked differences in their child-rearing practices. The children of the Tohono O'odham and Pima were probably allowed the greatest freedom of action. This does not imply that Tohono O'odham and Pima children went untrained: they were expected to recognize seniority and show respect for age, regardless of sex; to promote group solidarity; and to respect the role, function, and opinion of every member of the band. Children were considered accomplished provided they made age-appropriate progress in these areas and in contributing to the group's subsistence.

In contrast, Pueblo children were subjected to extremes of control. These tribes stressed life-crisis ceremonies that offered symbolic resolution to the major problems faced by the community. Children who failed to reach certain (usually behavioural) benchmarks in a timely manner were pushed in prescribed ways to meet the standard. For example, all Hopi children participated in the kachina (katsina) ceremony at about seven years of age; its purpose was to initiate them into the tribe and to facilitate their introduction to the supernatural. During the ceremony, it is reported that all the children were ritually whipped to exorcise evil influences, but those children who frequently misbehaved or showed a lack of self-control were whipped more severely than the others.

Belief and aesthetic systems

Like most Native American religions, those of the Southwest Indians were generally characterized by animism and shamanism. Animists perceive the world as filled with living entities: spirit-beings that animate the sun, moon, rain, thunder, animals, plants, topographic features, and many other natural phenomena. Shamans are men and women who have achieved a level of knowledge or power regarding physiological and spiritual health, especially its maintenance, recovery, or destruction. Always in a somewhat liminal state, shamans had to be acutely aware of the community's goings-on or risk the consequences: a number of 19th-century accounts report the execution of Pima shamans who were believed to have caused people to sicken and die.

The spectacular, communally-centred Pueblo ceremonies (rite of passage) for rain and growth reflected a conception of the universe in which every person, animal, plant, and supernatural being was considered significant. Without the active participation of every individual in the group, it was believed that the life-giving sun would not return from his “winter house” after the solstice, the rain would not fall, and the crops would not grow. In fact, Pueblo groups generally believed that the cosmic order was in perpetual danger of breaking down and that an annual cycle of ceremonies was a crucial factor in the continued existence of the world.

In the Pueblo view, humans affected the world through their actions, emotions, and attitudes, among other things, and communities that fostered metaphysical harmony were visited by spirit-beings called kachinas (kachina) (katsinas) each year. The number and form of the spirit-beings varied from one community to the next and reflected the concerns and consequences of life in a desert environment. Many of the more than 500 kachinas known to scholars were spirits of corn, squash, and rain; there were also kachinas of trickster clowns, ogres, hunters, and many animals. Each individual kachina had a distinctive appearance, and during annual rituals they were thought to possess or share the bodies of dancers whose regalia matched that appearance. Small representations of kachinas were made for children; they were beautiful objects as well as useful items for teaching cultural traditions. The kachina religion was most active among the western Pueblos and was less important as one traveled east.

In the Pueblo view, humans affected the world through their actions, emotions, and attitudes, among other things, and communities that fostered metaphysical harmony were visited by spirit-beings called kachinas (kachina) (katsinas) each year. The number and form of the spirit-beings varied from one community to the next and reflected the concerns and consequences of life in a desert environment. Many of the more than 500 kachinas known to scholars were spirits of corn, squash, and rain; there were also kachinas of trickster clowns, ogres, hunters, and many animals. Each individual kachina had a distinctive appearance, and during annual rituals they were thought to possess or share the bodies of dancers whose regalia matched that appearance. Small representations of kachinas were made for children; they were beautiful objects as well as useful items for teaching cultural traditions. The kachina religion was most active among the western Pueblos and was less important as one traveled east. The Apache conceived of the universe as inhabited by a great variety of powerful entities, including animals, plants, witches (evil shamans), superhuman beings, rocks, and mountains. Each could exert force in the world for good or ill and required individual propitiation. Each was personalized, talked to, sung to, scolded, or praised. Apache ceremonies were concerned mainly with the magical coercion of these powerful entities for the curing of disease and the acquisition of personal success in hunting and warfare.

The Apache conceived of the universe as inhabited by a great variety of powerful entities, including animals, plants, witches (evil shamans), superhuman beings, rocks, and mountains. Each could exert force in the world for good or ill and required individual propitiation. Each was personalized, talked to, sung to, scolded, or praised. Apache ceremonies were concerned mainly with the magical coercion of these powerful entities for the curing of disease and the acquisition of personal success in hunting and warfare. Navajo ceremonies were based on an elaboration of a similarly animistic view of the universe, with the power sources both diffuse and specific. Power was localized in a great many autonomous beings who were dangerous and unpredictable. These were of two classes: Earth Surface People (human beings, ghosts, and witches) and Holy People (supernaturals who could aid or harm Earth Surface People by sending sickness). As they turned away from hunting and raiding in favour of agriculture and herding, the Navajo focused their attention on elaborate rituals or “sings” that aimed to cure sickness and bring an individual into harmony with his family group, nature, and the supernatural (see Blessingway).

Navajo ceremonies were based on an elaboration of a similarly animistic view of the universe, with the power sources both diffuse and specific. Power was localized in a great many autonomous beings who were dangerous and unpredictable. These were of two classes: Earth Surface People (human beings, ghosts, and witches) and Holy People (supernaturals who could aid or harm Earth Surface People by sending sickness). As they turned away from hunting and raiding in favour of agriculture and herding, the Navajo focused their attention on elaborate rituals or “sings” that aimed to cure sickness and bring an individual into harmony with his family group, nature, and the supernatural (see Blessingway).In contrast to the animistic religions of other Southwest tribes, the River Yumans believed that a single animating principle or deity was the source of all supernatural power. There was only one medium, dreaming, for acquiring the supernatural protection, guidance, and power that were considered necessary for success in life. Sequences of traditional myths acquired through dreaming were converted into songs and acted out in ceremonies. The pursuit of such power sometimes caused an individual religious or war leader to abandon all other activities—farming, food collecting, and even hunting. It seems to have been no coincidence that this form of spiritual quest occurred only where one could count on regular and plentiful crops.

The religion of the Tohono O'odham seems to reflect their position between the River Yumans and the Pueblos. Not only did they “sing for power” and go on individual vision quests like the former, but they also held regular communal ceremonies to keep the world in order.

Cultural continuity and change

Traditionally, each community in the Southwest culture area tried to maintain a delicate balance between population and natural resources. If the population outgrew the capacities of the resource base, a segment might split off and form a colony in a favourable habitat resembling that of its parent group. Under normal conditions the new colony was so constituted to reproduce as far as possible the parent culture even in its most esoteric aspects. If prolonged drought occurred, an entire community might migrate. Alternatively human pressures from without, such as raids by marauding bands or aggressive missionization, could cause a tribe to consolidate and move to more easily defended sites. In the 1700s, for instance, Tohono O'odham settlements consolidated into large compact villages for defense against the Apache.

Colonization and resistance

Spain hoped to gain gold, slaves, and converts to Roman Catholicism from its New World colonies; soldiers and missionaries who undertook the work of conquest were promised a portion of those riches. Not surprisingly, rumours of golden cities soon abounded, though of course none were actually discovered. In 1536 the Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar) recounted stories of golden cities rumoured to be somewhere in the North American interior. His report spurred the government to sponsor an exploratory trip by the friar Marcos de Niza (Niza, Marcos de) (1539), who reported seeing from afar cities of vast riches. These were probably the Zuni pueblos and the friar's mistake is understandable given that the Zuni towns were larger than many of the Spanish outposts in Mexico.

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (Coronado, Francisco Vázquez de) subsequently led an expedition (1540–42) that included some 300 soldiers, several missionaries, approximately 1,000 indigenous labourers, and some 1,000 pack animals. Overwintering on the Rio Grande, Coronado demanded provisions from nearby pueblos; his men also molested several Pueblo women. Indigenous resistance was met with force: the Spanish executed some 200 Pueblo individuals, many through burning at the stake; Spain was in the throes of the inquisition during this period, the methods of which had been quickly transferred to the Americas. The surviving Pueblos in the area were horrified and they fled.

Permanent colonial occupation of the Southwest was initiated in 1598 under the leadership of Juan de Oñate (Oñate, Juan de), who had been commissioned to found a series of Spanish towns in the region. When Oñate's troops met with resistance at Acoma pueblo in 1599, they killed perhaps 800 of the town's 6,000 residents. The 80 surviving men of Acoma were punished by the amputation of a foot, the women and adolescents were sentenced to 20 years of slavery, and children under age 12 were given to the missions.

Permanent colonial occupation of the Southwest was initiated in 1598 under the leadership of Juan de Oñate (Oñate, Juan de), who had been commissioned to found a series of Spanish towns in the region. When Oñate's troops met with resistance at Acoma pueblo in 1599, they killed perhaps 800 of the town's 6,000 residents. The 80 surviving men of Acoma were punished by the amputation of a foot, the women and adolescents were sentenced to 20 years of slavery, and children under age 12 were given to the missions.The next eight decades saw the spread of Catholicism and the establishment of the encomienda, a system of tribute paid through indigenous labour and foodstuffs. Although these changes were burdensome, the penalties the Pueblos felt for engaging in traditional religious activities such as kachina dances were far worse. These rituals were seen by the Catholic priests as abominations, and, in order to stamp out traditional religion, the missionaries destroyed regalia and punished religious leaders severely; reports of tortures such as flaying and dismemberment are common during this period.

By about 1770 it had become increasingly clear to the Pueblos that the world was sliding into chaos. In addition to deaths from torture and execution, many Pueblos died during recurrent epidemics of smallpox and other Old World diseases to which they had little resistance. Further, the Apachean tribes had begun to raid freely; raids combined with a series of devastating droughts and the encomienda to cause mass starvation in the pueblos. Given their worldview, the Pueblo peoples thought it imperative to reestablish their religious observances. In 1680 they effected an organized revolt against the Spanish, killing nearly all the Catholic priests and driving the conquerors out of the region (see Pueblo Rebellion).

Accommodation and cultural preservation

Between 1680 and 1692 the Pueblos were free from foreign rule. When soldiers and missionaries returned they employed a divide and conquer process, overcoming each pueblo individually; by 1696 Spanish rule again prevailed in the Southwest. Having had a period in which to reorganize and reevaluate their position vis-à-vis the colonizers, the Pueblos appeared to accede to missionization. They did not, however, abandon their traditional religious and cultural practices; instead, they took such practices underground and thus preserved many aspects of their pre-Columbian cultural traditions.

With differing levels of exposure to colonial conquest, it is to be expected that the traditions of the eastern and western Pueblos were differentially preserved. Unless totally destroyed, the western Pueblos did not surrender structurally to foreign control. Social organization among these groups was characterized by robust and cross-cutting levels of clan and secret society memberships; these were rather easily disguised and the people were thus able to resist (or only superficially absorb) externally imposed social change.

In contrast, the eastern Pueblos had more centralized forms of social organization based on moieties; the moieties, in turn, were the foundation of both civil and spiritual life. When combined with the greater levels of subjugation to which these groups were exposed, the moiety systems proved vulnerable to attack at both the sociopolitical and the ceremonial levels. Most of the eastern Pueblos incorporated at least some aspects of the Spanish system into their own structures, creating a syncretic blend of the two. The Tohono O'odham produced their own Christian sect, a blend of native and mission practices known as Sonoran Catholicism.

During the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the Apachean tribes fought the foreign control of the Spanish and attempted to gain and hold territory surrounding the Pueblo communities. They also took note of the material conditions of these groups—indigenous and Spanish— and selectively incorporated such things as horses, sheep, cattle, woven goods, and dry land agricultural techniques. While fiercely preserving their unique tribal identities, the Apacheans also engaged in a long period of cultural acquisition and remodeling.

In the 19th century, a period of relative peace for the Pueblo groups, the Apachean peoples encountered considerable difficulty. During this period the Southwest was ceded by Spain to Mexico (1821) and later became part of the United States (1848). Although the American Civil War slowed U.S. colonization of the region, Apachean actions against settlers were reported in newspapers and caused great public outcry. In 1863, Kit Carson (Carson, Kit) was ordered to pacify the Navajo and led U.S. Army forces in the systematic destruction of the tribe's fields and livestock. Carson's forces captured some 8,000 Navajo who subsequently endured the “Long Walk” from their homeland near Canyon de Chelly (Canyon de Chelly National Monument) in northeastern Arizona to Fort Sumner, N.M., some 300 miles away; they were interred at the nearby Bosque Redondo camp from 1864 to 1868. After their release, the Navajo returned to their communities and began the rebuilding process.

The Apache were more difficult to conquer, particularly as several incidents of treachery, rape, and murder by members of the U.S. military instigated extreme wariness on the part of these tribes. Military pressure did cause some of the more sedentary Apache bands to move to reservations (reservation) following the Civil War, but many did not trust promises of peace and chose to flee to the canyon country of the Colorado Plateau or southward, to Mexico. Although most were captured and removed to reservations by 1875, others, led by luminaries including Geronimo, continued to engage in spirited resistance until their final capture in 1886. Those who had continued armed resistance were transported to Florida, and later to Alabama, only returning to the Southwest in 1894. Geronimo, however, was seen as a figurehead of resistance and so was not allowed to return; he died in custody in 1909.

The 20th and 21st centuries

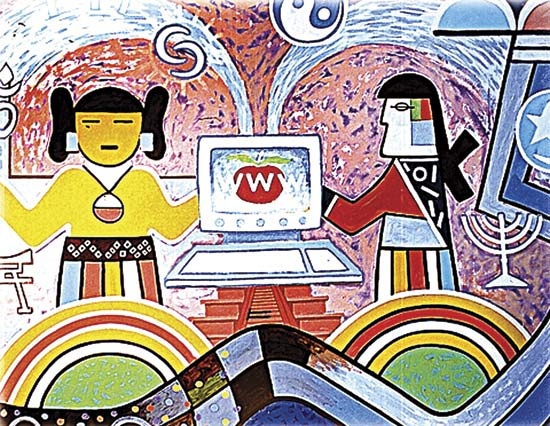

The processes of change accelerated at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. The isolation of the region had combined with its arid climate and the fierce resistance of the Apacheans to slow Euro-American settlement and urbanization. At the same time military defeat, the loss of traditional lands, and missionary efforts to change their religious beliefs and practices had fostered among many tribes a sense of rejection and bitterness against colonizers.

U.S. (United States) policies towards indigenous peoples in most of the 20th century were disparate and often unevenly applied, but shared the common goal of assimilation. In the first half of the century tribal governments were developed and empowered with legal authority. A variety of rural development projects also took place, including rural electrification and the building of schools, hospitals, irrigation systems, highways, and telephone lines. The 1950s, '60s, and '70s saw the advancement of a policy called termination, in which many tribes lost their status as sovereign entities; by the late 20th century some “terminated” Southwestern groups had filed petitions to regain federal status.

Despite rural development and other projects, reservation life remained generally difficult when compared to that of the rest of the American population, especially among the Tohono O'odham, Hopi, Fort Apache, and some of the highland Yuman tribes. Farming and sheep operations remained economic mainstays in much of the region. The reassignment of a substantial portion of Hopi common lands to the Navajo, an action that the Hopi claim abrogated federal treaties, contributed to Hopi impoverishment; although the federal judiciary ruled the taking was legal and the United States Congress in 1996 passed legislation it hoped would resolve the dispute, the reassignment remained a point of contention into the 21st century.

Despite rural development and other projects, reservation life remained generally difficult when compared to that of the rest of the American population, especially among the Tohono O'odham, Hopi, Fort Apache, and some of the highland Yuman tribes. Farming and sheep operations remained economic mainstays in much of the region. The reassignment of a substantial portion of Hopi common lands to the Navajo, an action that the Hopi claim abrogated federal treaties, contributed to Hopi impoverishment; although the federal judiciary ruled the taking was legal and the United States Congress in 1996 passed legislation it hoped would resolve the dispute, the reassignment remained a point of contention into the 21st century. By the early 21st century the tribes of the Southwest had formed a variety of business development units, tribally-owned enterprises, and other economic ventures. Many had developed tourism programs; these in turn provided jobs and a venue for the sale of indigenous arts such as jewelry, pottery, and textiles. Some tribes chose to allow the development of their rich mineral resources, principally coal and uranium, under closely monitored conditions. However, the ecological and spiritual costs of large mining operations made many skeptical of this form of development. See also Native American: History (Native American); Native American: Developments in the late 20th and early 21st centuries (Native American).

By the early 21st century the tribes of the Southwest had formed a variety of business development units, tribally-owned enterprises, and other economic ventures. Many had developed tourism programs; these in turn provided jobs and a venue for the sale of indigenous arts such as jewelry, pottery, and textiles. Some tribes chose to allow the development of their rich mineral resources, principally coal and uranium, under closely monitored conditions. However, the ecological and spiritual costs of large mining operations made many skeptical of this form of development. See also Native American: History (Native American); Native American: Developments in the late 20th and early 21st centuries (Native American).Additional Reading

Regional syntheses of the traditional cultures of the Southwest include William C. Sturtevant (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 9 and 10, Southwest, ed. by Alfonso Ortiz (1979–83); Linda S. Cordell, Prehistory of the Southwest (1984); and Trudy Griffin-Pierce, Native Peoples of the Southwest (2000), and The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southwest (2007).Syntheses of particular aspects of Southwest Indian culture and history include 19th-century U.S. Army surgeon Washington Matthews, Navaho Myths Prayers and Songs, ed. by P.E. Goddard (1907, reprinted 1964); Edward H. Spicer, Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on the Indians of the Southwest, 1533–1960 (1962); John Collier and Ira Muskowitz, Patterns and Ceremonials of the Indians of the Southwest (1949, reissued as American Indian Ceremonial Dances, 1972); Ruth M. Underhill, Ceremonial Patterns in the Greater Southwest (1948, reissued 1966); Steven A. LeBlanc, Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest (1999); James F. Brooks, Captives & Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (2002); and R. Warren Metcalf, Termination's Legacy: The Discarded Indians of Utah (2002).Classic studies of tribes in the western and southern areas within the region include C. Daryll Forde, Ethnography of the Yuma Indians (1931, reissued 1965); Leslie Spier, Yuman Tribes of the Gila River (1933, reprinted 1978); Ruth M. Underhill, Singing for Power: The Song Magic of the Papago Indians of Southern Arizona (1938, reissued 1993); Alice Joseph, Rosamond B. Spicer, and Jane Chesky, The Desert People (1949, reprinted 1974), also on the Tohono O'odham (Pima-Papago); and William H. Kelly, The Papago Indians of Arizona (1963, reissued 1974).Studies of Pueblo tribes include Elsie Clews Parsons, Pueblo Indian Religion, 2 vol. (1939, reprinted 1974); Fred Eggan, Social Organization of the Western Pueblos (1950, reissued 1973); Charles H. Lange, Cochití: A New Mexico Pueblo, Past and Present (1960, reissued 1990); Alfonso Ortiz, The Tewa World (1969); Edward P. Dozier, The Pueblo Indians of North America (1970, reissued 1983); Joe S. Sando, Pueblo Nations: Eight Centuries of Pueblo Indian History (1992); Bill Wright, The Tiguas: Pueblo Indians of Texas (1993); Dorothea C. Leighton and John Adair, People of the Middle Place: A Study of the Zuni Indians (1966); C. Gregory Crampton, The Zunis of Cibola (1977); T.J. Ferguson et al., A Zuni Atlas (1985); Laura Thompson and Alice Joseph, The Hopi Way (1944, reissued 1965); and John D. Loftin, Religion and Hopi Life in the Twentieth Century (1991).Studies of the Apachean tribes include Clyde Kluckhohn and Dorothea Leighton, The Navaho, rev. ed., ed. by Lucy H. Wales and Richard Kluckhohn (1962, reissued 1974); Peter Iverson, The Navajo Nation (1981); James M. Goodman and Mary E. Goodman, The Navajo Atlas: Environments, Resources, People, and History of the Diné Bikeyah (1982); Garrick Bailey and Roberta Glenn Bailey, A History of the Navajos: The Reservation Years (1986), an economic and cultural history; Raymond Friday Locke, The Book of the Navajo, 5th ed. (1992), a nontraditional, sociocultural history; Morris Edward Opler, An Apache Life-Way: The Economic, Social, and Religious Institutions of the Chiricahua Indians (1941, reissued 1965); Donald E. Worcester, The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest (1979); James L. Haley, Apaches: A History and Culture Portrait (1981); Richard J. Perry, Western Apache Heritage: People of the Mountain Corridor (1991); and Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the WesternApache (1996). Ed.

- William H Crawford

- William Heath Robinson

- William Hedley

- William Heinemann

- William Heinesen

- William Henry

- William Henry and Katharine O'Shea

- William Henry Ashley

- William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge

- William Henry Beveridge Beveridge, 1st Baron

- William Henry Davies

- William Henry Dines

- William Henry Drummond

- William Henry Eccles

- William Henry Fox Talbot

- William Henry Harrison

- William Henry Harrison: Inaugural Address

- William Henry Holmes

- William Henry Ireland

- William Henry Jackson

- William Henry Pickering

- William Henry Twenhofel

- William Henry Vanderbilt

- William Henry Waddington

- William Henry Webb