cultural evolution

social science

Introduction

the development of one or more cultures from simpler to more complex forms. The subject may be viewed as a unilinear phenomenon that describes the evolution of human behaviour as a whole, or it may be viewed as a multilinear phenomenon, in which case it describes the evolution of individual cultures or societies (or of given parts of a culture or society).

Unilinear cultural evolution was an important concept in the emerging field of anthropology during the 18th and 19th centuries but fell out of favour in the early 20th century. Scholars began to propagate theories of multilinear cultural evolution in the 1930s, and these neoevolutionist (neoevolutionism) perspectives continue, in various forms, to frame much of the research undertaken in physical anthropology and archaeology, the branches of anthropology (anthropology) that focus on change over time.

Unilinear theory

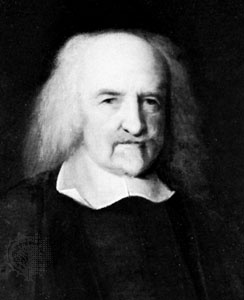

The Age of Discovery (European exploration) introduced 15th- and 16th-century Europeans to a wide variety of “primitive” cultures. Almost immediately, European intellectuals began efforts to explain how and why the human condition had come to be so diverse. Although the 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (Hobbes, Thomas) was very much mistaken when he described indigenous peoples as living in conditions in which there were “no arts, no letters, no society” and experiencing life as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” his description encapsulates the era's popular conception of the “savage.” Ignoring or unaware of a variety of facts—many indigenous peoples enjoyed a much better standard of living than European peasants (peasant), for instance—Hobbes and other scholars posited that everything that was good and civilized resulted from the slow development away from this “lowly” state and toward the “higher” state represented by the cultures of Europe. Even rationalistic philosophes such as Voltaire implicitly assumed that the “upward” progress of humankind was part of the natural order.

The Age of Discovery (European exploration) introduced 15th- and 16th-century Europeans to a wide variety of “primitive” cultures. Almost immediately, European intellectuals began efforts to explain how and why the human condition had come to be so diverse. Although the 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (Hobbes, Thomas) was very much mistaken when he described indigenous peoples as living in conditions in which there were “no arts, no letters, no society” and experiencing life as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” his description encapsulates the era's popular conception of the “savage.” Ignoring or unaware of a variety of facts—many indigenous peoples enjoyed a much better standard of living than European peasants (peasant), for instance—Hobbes and other scholars posited that everything that was good and civilized resulted from the slow development away from this “lowly” state and toward the “higher” state represented by the cultures of Europe. Even rationalistic philosophes such as Voltaire implicitly assumed that the “upward” progress of humankind was part of the natural order.This Enlightenment notion that there was, in fact, a “natural order” derived from the philosophers of ancient Greece, who had described the world as comprising a Great Chain of Being—a view in which the world is seen as complete, orderly, and susceptible to systematic analysis. As a result, scholarship during the Enlightenment emphasized categorization and soon produced various typologies (typology) that described a series of fixed stages of cultural evolution.

Most focused on three major stages, but some posited many more categories. For instance, in his Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'esprit humain (1795; Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind), the Marquis de Condorcet (Condorcet, Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, marquis de) listed 10 stages, or “epochs,” of cultural evolution. He posited that the final epoch had begun with the French Revolution and was destined to usher in universal human rights and the perfection of the human race. The Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgenson Thomsen (Thomsen, Christian Jürgensen) is widely acknowledged as the first scholar to have based such a typology on firm data rather than speculation. In Ledetraad til nordisk Oldkyndighed (1836; A Guide to Northern Antiquities), he categorized ancient European societies on the basis of their tools, calling the developmental stages the Stone, Bronze, and Iron ages.

Most focused on three major stages, but some posited many more categories. For instance, in his Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'esprit humain (1795; Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind), the Marquis de Condorcet (Condorcet, Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, marquis de) listed 10 stages, or “epochs,” of cultural evolution. He posited that the final epoch had begun with the French Revolution and was destined to usher in universal human rights and the perfection of the human race. The Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgenson Thomsen (Thomsen, Christian Jürgensen) is widely acknowledged as the first scholar to have based such a typology on firm data rather than speculation. In Ledetraad til nordisk Oldkyndighed (1836; A Guide to Northern Antiquities), he categorized ancient European societies on the basis of their tools, calling the developmental stages the Stone, Bronze, and Iron ages. In the later 19th century, theories of cultural evolution were enormously influenced by the wide acceptance of the theory of biological evolution put forward by Charles Darwin (Darwin, Charles) in The Origin of Species (1859). Social scientists found that the framework suggested by biological evolution offered an attractive solution to their questions regarding the origins and development of social behaviour. Indeed, the idea of a society as an evolving organism was a biological analogy that was taken up by many anthropologists and sociologists and that persisted in some quarters even into the 20th century.

In the later 19th century, theories of cultural evolution were enormously influenced by the wide acceptance of the theory of biological evolution put forward by Charles Darwin (Darwin, Charles) in The Origin of Species (1859). Social scientists found that the framework suggested by biological evolution offered an attractive solution to their questions regarding the origins and development of social behaviour. Indeed, the idea of a society as an evolving organism was a biological analogy that was taken up by many anthropologists and sociologists and that persisted in some quarters even into the 20th century.The English philosopher Herbert Spencer (Spencer, Herbert) was among the first to work out a general evolutionary scheme that included human societies from across the globe. He held that human cultures evolved from less-complex “species” to those that were more so: people at first lived in undifferentiated hordes; then developed social hierarchies with priests, kings, scholars, workers, and so forth; and later accumulated knowledge that was differentiated into the various sciences. In short, human societies evolved, by means of an increasing division of labour, into complex civilizations.

The anthropologists E.B. Tylor (Tylor, Sir Edward Burnett) in England and Lewis H. Morgan (Morgan, Lewis Henry) in the United States were the chief exponents of cultural stages in the evolution of humankind. They emphasized the analysis of culture in general, not that of individual cultures, except as the latter might illustrate their theories of the overall evolution of humanity and civilization. Morgan summed up the precepts of the unilineal approach quite well:Since mankind were one in origin, their career has been essentially one, running in different but uniform channels upon all continents, and very similarly in all the tribes and nations of mankind down to the same status of advancement. It follows that the history and experience of the American Indian tribes represent, more or less nearly, the history and experience of our own remote ancestors when in corresponding conditions.

The anthropologists E.B. Tylor (Tylor, Sir Edward Burnett) in England and Lewis H. Morgan (Morgan, Lewis Henry) in the United States were the chief exponents of cultural stages in the evolution of humankind. They emphasized the analysis of culture in general, not that of individual cultures, except as the latter might illustrate their theories of the overall evolution of humanity and civilization. Morgan summed up the precepts of the unilineal approach quite well:Since mankind were one in origin, their career has been essentially one, running in different but uniform channels upon all continents, and very similarly in all the tribes and nations of mankind down to the same status of advancement. It follows that the history and experience of the American Indian tribes represent, more or less nearly, the history and experience of our own remote ancestors when in corresponding conditions.This passage is from Morgan's masterwork Ancient Society (1877), in which he also described seven stages of cultural evolution: lower, middle, and upper savagery; lower, middle, and upper barbarism; and civilization. He supported his ideas by citing contemporary societies characteristic of each stage except lower savagery, of which there were no extant examples.

Morgan's work was very widely read and became the basis for further developments in anthropology, perhaps most notably its emphasis on cross-cultural comparison and its preoccupation with the mechanisms of change. His work underlay debates on matters, such as the relative importance of technological innovation (versus diffusion), that were of serious concern for the remainder of the 19th century and persisted well into the 20th. However, although it is considered important in the history of anthropology, Morgan's work, and indeed unilineal cultural evolution as a whole, no longer hold credence in the field.

Multilinear theory

A widespread reaction against sweeping generalizations about culture began in the late 19th century in the United States and somewhat later in Europe. Theories and descriptions of hypothetical stages of evolution generally, and of unilinear evolution specifically, were heavily criticized as racist; instead of presuming that some peoples were more evolved than others, the new trend was to regard all cultures as unique in time and place. In the United States this movement, known as cultural particularism, was led by the German-born anthropologist Franz Boas (Boas, Franz).

A widespread reaction against sweeping generalizations about culture began in the late 19th century in the United States and somewhat later in Europe. Theories and descriptions of hypothetical stages of evolution generally, and of unilinear evolution specifically, were heavily criticized as racist; instead of presuming that some peoples were more evolved than others, the new trend was to regard all cultures as unique in time and place. In the United States this movement, known as cultural particularism, was led by the German-born anthropologist Franz Boas (Boas, Franz).Boas and several generations of his students—including A.L. Kroeber (Kroeber, A.L.), Ruth Benedict (Benedict, Ruth), and Margaret Mead (Mead, Margaret)—turned completely away from broad generalizations about culture and concentrated on fieldwork among traditional peoples, harvesting a great variety of facts and artifacts as empirical evidence of cultural processes within existing societies. The creation of encyclopaedic lists of cultural traits and changes therein led to the development of “culture histories” and dominated American anthropology for the first half of the 20th century. The culture history movement so influenced anthropology that grand theories of “Man” became far less common than in the past.

By mid-century, however, a number of American anthropologists, including Leslie A. White (White, Leslie A.), Julian H. Steward (Steward, Julian), Marshall D. Sahlins, and Elman R. Service (Service, Elman Rogers), had revived theoretical discussions regarding cultural change over time. They rejected universal stages outright, instead conceptualizing cultural evolution as “multilinear”—that is, as a process consisting of a number of forward paths of different styles and lengths. They posited that while no specific evolutionary changes are experienced by all cultures universally, human societies do generally evolve or progress. They further suggested that the primary mechanism for such progress involved technological breakthroughs that make societies more adaptable to and dominant over the environment; technology, in this case, was quite broadly conceived, and included such developments as improvements in tool forms or materials (as with the transition through the Stone, Bronze, and Iron ages and later the Industrial Revolution), transportation (as from pedestrian to equestrian to motorized forms), and food production (as from hunting and gathering to agriculture). Proponents of multilinear evolution hold that only in this sense can the whole of world culture be viewed as the product of a unitary process.

- John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

- John de Vere Oxford, 13th Earl of

- John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey

- John de Warenne Surrey, 7th Earl of

- John Dewey

- John Dexter

- John Dickinson

- John Dickson Carr

- John Digby, 1st earl of Bristol

- John Digby Bristol, 1st earl of

- John Dillinger

- John Dillon

- John D. MacDonald

- John Dollond

- John Donne

- John Dos Passos

- John Dowland

- John Drew, Jr.

- John Drew, Sr.

- John Drinkwater

- John D. Rockefeller

- John D. Rockefeller, III

- John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

- John Dryden

- John Dunmore Lang