Sudan, The

Introduction

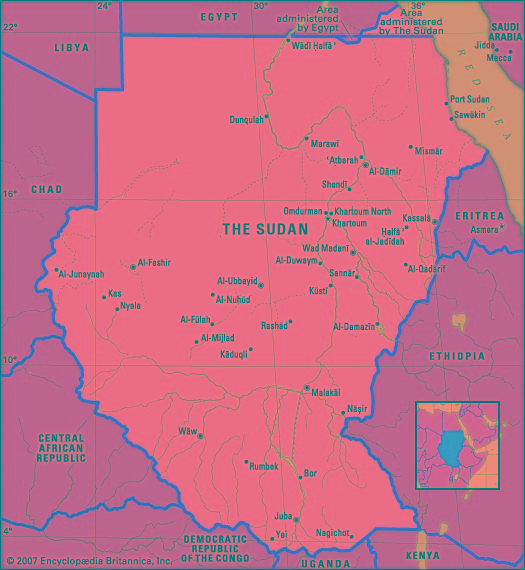

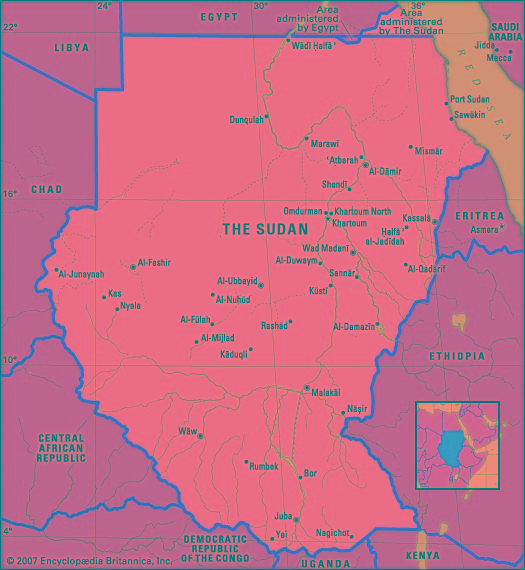

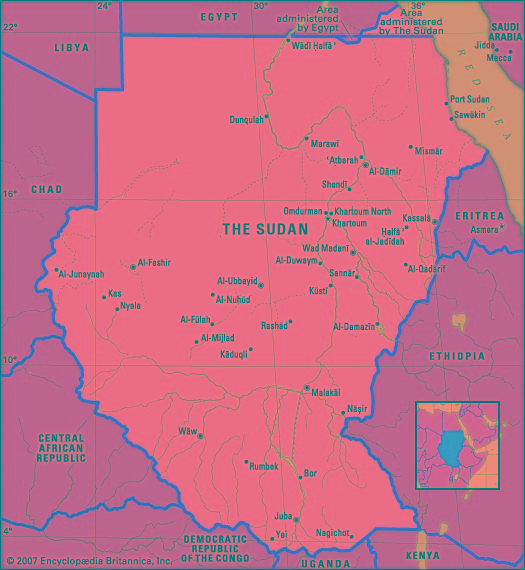

Sudan, flag of The country located in northeastern Africa. It is bounded on the north by Egypt; on the east by the Red Sea and Ethiopia; on the south by Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; on the west by the Central African Republic and Chad; and on the northwest by Libya. The largest African country, The Sudan has an area that represents more than 8 percent of the African continent and almost 2 percent of the world's total land area. Khartoum, the national capital, is located in the northern half of the country at the junction of the Blue (Blue Nile River) and White Nile rivers (White Nile River). The name Sudan derives from the Arabic expression bilād as-Sūdān (“land of the blacks”), by which medieval Arab geographers referred to the settled African countries that began at the southern edge of the Sahara.

country located in northeastern Africa. It is bounded on the north by Egypt; on the east by the Red Sea and Ethiopia; on the south by Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; on the west by the Central African Republic and Chad; and on the northwest by Libya. The largest African country, The Sudan has an area that represents more than 8 percent of the African continent and almost 2 percent of the world's total land area. Khartoum, the national capital, is located in the northern half of the country at the junction of the Blue (Blue Nile River) and White Nile rivers (White Nile River). The name Sudan derives from the Arabic expression bilād as-Sūdān (“land of the blacks”), by which medieval Arab geographers referred to the settled African countries that began at the southern edge of the Sahara.

country located in northeastern Africa. It is bounded on the north by Egypt; on the east by the Red Sea and Ethiopia; on the south by Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; on the west by the Central African Republic and Chad; and on the northwest by Libya. The largest African country, The Sudan has an area that represents more than 8 percent of the African continent and almost 2 percent of the world's total land area. Khartoum, the national capital, is located in the northern half of the country at the junction of the Blue (Blue Nile River) and White Nile rivers (White Nile River). The name Sudan derives from the Arabic expression bilād as-Sūdān (“land of the blacks”), by which medieval Arab geographers referred to the settled African countries that began at the southern edge of the Sahara.

country located in northeastern Africa. It is bounded on the north by Egypt; on the east by the Red Sea and Ethiopia; on the south by Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; on the west by the Central African Republic and Chad; and on the northwest by Libya. The largest African country, The Sudan has an area that represents more than 8 percent of the African continent and almost 2 percent of the world's total land area. Khartoum, the national capital, is located in the northern half of the country at the junction of the Blue (Blue Nile River) and White Nile rivers (White Nile River). The name Sudan derives from the Arabic expression bilād as-Sūdān (“land of the blacks”), by which medieval Arab geographers referred to the settled African countries that began at the southern edge of the Sahara.Since ancient times the Sudan has been an arena for interaction between the cultural traditions of Africa and those of the Mediterranean world. In recent centuries Islām and the Arabic language have achieved ascendancy in many northern parts of the country, while older African languages and cultures predominate in the south. Large parts of the country continue to rely on an agricultural and pastoral subsistence economy, but commercial agriculture—together with more limited mining and industrial development—plays a central role in the northern districts and in the national economy as a whole.

The country has had numerous changes in government since independence in 1956. Successive regimes found it difficult to win general acceptance from the country's diverse political constituencies, a situation symbolized by the lack of a formal constitution until 1973. An early conflict arose between those northern leaders who hoped to impose unity upon the nation through the vigorous extension of Islāmic law and culture to all parts of the country and those who opposed this policy; the latter included the majority of southerners and those northerners who favoured a secular government.

From independence until 1972 there prevailed a costly and divisive civil war, fought largely in the south but punctuated by violent incidents in the capital. The Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972 ended the conflict only temporarily, and in 1983 the civil war resumed. By this time the comparative lack of economic development in the south had become a new source of regional grievance, and northern leaders' continuing attempts to Islāmize the Sudanese legal system proved an even more potent source of discord. The failure in the 1970s of an array of costly development projects in commercial agriculture left the national economy stagnant and debt-ridden. As a result, many Sudanese began to experience a significant decline in living standards in the late 1970s that has continued to the present.

The land

Relief

The Sudan (Sudan, The) is mainly composed of vast plains and plateaus that are drained by the middle and upper Nile River and its tributaries. This river system runs from south to north across the entire length of the east-central part of the country. The immense plain of which The Sudan is composed is bounded on the west by the Nile-Congo watershed and the highlands of Darfur and on the east by the Ethiopian Plateau and the Red Sea Hills (ʿAtbāy (Itbāy)). This plain can be divided into a northern area of rock desert that is part of the Sahara; (Sahara) the western Qawz, an area of undulating sand dunes that merges northward into the rock desert; and a central and southern clay plain, the centre of which is occupied by an enormous swampy region known as As-Sudd (Sudd, Al-) (the Sudd).

Most of the northern Sudan is a sand- or gravel-covered desert, diversified by flat-topped mesas of Nubian sandstone and islandlike steep-sided granite hills. In the central Sudan the clay plain is marked by inselbergs (inselberg) (isolated hills rising abruptly from the plains), the largest group of which forms the Nuba Mountains (Jibāl An-Nūbah). The western plain is composed primarily of Nubian sandstones, which form a dissected plateau region with flat-topped mesas and buttes. The volcanic highlands of the Marra Mountains (Marrah Mountains) rise out of the Darfur Plateau farther west to altitudes of between approximately 3,000 and 10,000 feet (900 and 3,000 metres) above sea level. These mountains form the Nile-Congo watershed and the western boundary of the central plain.

In the northeastern Sudan, the Red Sea Hills region is an uplifted escarpment. The scarp slope facing the Red Sea forms rugged hills that are deeply incised by streams. The escarpment overlooks a narrow coastal plain that is 10 to 25 miles (16 to 40 kilometres) wide and festooned with dunes and coral reefs. Farther south the eastern uplands constitute the foothills of the Ethiopian highland massif.

In the southern Sudan there are two contrasting upland areas. The Ironstone Plateau lies between the Nile-Congo watershed and the southern clay plain; its level country is marked with inselbergs. On the Uganda border there are massive ranges with peaks rising to more than 10,000 feet. The Imatong Mountains contain Mount Kinyeti (10,456 feet), the highest in The Sudan.

Drainage and soils

The Nile River system is the dominant physical feature, and all streams and rivers of The Sudan drain either into or toward the Nile. The White Nile (Baḥr Al-Abyaḍ) enters the country as the Mountain Nile ( Baḥr al-Jabal) from the south through rapids at Nimule on the Uganda border. After its confluence with the left- (west-) bank tributary known as the Baḥr Al-Ghazāl, the Mountain Nile becomes the White Nile. A little farther north along its course, the White Nile receives much of its water from the right-bank Sobat River, which flows from the Ethiopian Plateau to join the Nile near Malakāl. The White Nile then loses much of its water in the swampy As-Sudd region as it flows northward to Khartoum. The White Nile continues to maintain an extremely low gradient until it is joined by the Blue Nile (Baḥr Al-Azraq) at Khartoum. The Blue Nile, which, like the Sobat, rises in the Ethiopian Plateau, contributes much of the floodwaters of the White Nile. After the confluence of the White and Blue Niles at Khartoum, the river flows in a great, curving northward course and is known simply as the Nile (Nahr An-Nīl).

Throughout much of the country drainage does not reach the Nile rivers; the rivers of the southwest infrequently reach the Baḥr Al-Ghazāl system, and to the north most hill groups initiate seasonal watercourses that are lost in the surrounding plains.

The surface of the deserts in the north and northeast are either bare rock, a mantle of bare waste, or sandy expanses of mobile dunes known as ergs (erg). In the semiarid zone of the north-central Sudan, the layer of rock waste is slightly modified to form immature soils; in the Qawz region, soils are brownish red and of low fertility. Alluvial soils occur at the desert deltas of Al-Qāsh (the Gash) and Barakah rivers, along the White and Blue Niles, and in the alluvial plains of the many small rivers radiating from the Marra Mountains.

The alkaline soils of the central and southern plains are heavy cracking clays. The soil of the Gezira (Al-Jazīrah (Jazīrah, Al-)) plain south of Khartoum is deep-cracking, uniform clay that has been deposited during the annual inundations of the Blue Nile, while the clays of As-Sudd were deposited in the area of impeded drainage.

Climate

In the northernmost Sudan northerly winds prevail for most of the year, and rainfall is rare; to the south of this the seasons are characterized by the oscillation, north and south, of the boundary between moist southerly air and dry northerly air. The latter phenomenon, more specifically, involves the seasonal migration and pulsation of the northern tropical continental air mass and the southern maritime continental air mass, which are divided by the intertropical convergence zone. In winter the north winds of the tropical air mass blow across The Sudan toward the front, which may be as far south as the Tropic of Capricorn. These winds are relatively cool and dry and usually bring no rain. By April the front begins to move northward across the country, and moist southerly air of the maritime air mass is drawn in from the South Atlantic Ocean. Because of this, the central and southern Sudan have rainy seasons, the total lengths of which vary according to their latitude.

The Sudan is a hot country, for temperatures are little mitigated by altitude. The central region has the highest mean annual temperatures; at Khartoum temperatures of more than 100° F (38° C) can be recorded during any month of the year. The highest temperatures normally occur just before the rainy season.

Rainfall varies from almost nothing in the north to more than 47 inches (1,200 millimetres) annually in the extreme south. Along the Red Sea the climate is alleviated by sea breezes, and most of the rain falls during winter. In the central and southern Sudan, precipitation usually occurs during the summer months. Dust storms are common in the north, while the rainy season lasts for eight to nine months a year in the south.

Plant and animal life

The Sudan has five main vegetational belts in succession from north to south, more or less in coincidence with rainfall patterns. The desert region in the north forms about one-fourth of the total area. It is followed southeastward by semidesert, low-rainfall and high-rainfall savanna (grassland) with inland floodplains, and mountain vegetation regions.

The desert region, with less than 3 inches of rainfall, supports permanent vegetation only near watercourses. The semidesert, with 3–11 inches of rainfall, supports a mixture of grasses and acacia scrub. Farther south, low-rainfall savannas appear that consist of grasses, thorny trees, and baobab trees. Acacia trees dominate these savannas, with one species, A. senegal, yielding the gum arabic which was long one of The Sudan's principal exports. With an annual precipitation of more than 30 inches, the high-rainfall savannas of the south-central Sudan are more lush, with rich grasses along the Nile that support a large number of cattle. The intermittent woodlands dotting this belt gradually merge southward with the true rain forest that is now found in only remnants of the southernmost portions of the country.

Large areas of The Sudan's natural vegetation have disappeared because of the effects of centuries of cultivation and because of grass fires that annually may sweep across more than half the country. Further dangers to plant life are the effects of overstocking, soil erosion, the lowering of the water table, and the advance of the desert into the central region.

The country's wildlife includes the lion, leopard, and cheetah, as well as the elephant, giraffe, zebra, wild ass, rhinoceros, buffalo, hippopotamus, ibex, wild sheep, and numerous varieties of antelope. The chimpanzee, baboon, and colobus monkey are found in the forests. Resident birds include bustards, guinea fowl, several kinds of partridge, geese, cranes, Egyptian vultures, storks, pelicans, plover, weaverbirds, shrikes, and starlings. Reptiles include crocodiles and various lizards. Insect life is abundant; mosquitoes infest the riverbanks and swamps, and seroot flies (large bloodsucking houseflies) are a scourge during the wet months. The tsetse fly is found south of latitude 12° N whenever suitable conditions occur.

Settlement patterns

Rural settlements in The Sudan are usually clustered along watercourses because of problems of water supply, especially during the dry months. In the north, villages are often strung out along the rivers. The types of houses built vary from north to south. In the north houses are made of sun-dried bricks and have flat-topped roofs, while in the central and southern portions of the country the people build round huts with thatched conical roofs made out of grass, millet stalks, and wooden poles. In the central Sudan walls constructed of millet stalks often surround building compounds.

Though towns are few and widely scattered, about one-fifth of The Sudan's population can be considered urban. The southern Sudan was the least urbanized region in 1956 but has since experienced a high rate of urban growth. Urbanization has also been relatively rapid in the states of Kurdufān and Dārfūr, respectively in the west-central and western Sudan, where trade is more highly developed. The high urban proportion of the population of Aʿālī An-Nīl (Upper Nile) state is attributable to Aṭbarahʿ, the administrative centre that contains the main workshops of Sudan Railways. The high proportion of urban population in Ash-Sharqīyah (Eastern) state is due to Port Sudan, The Sudan's major outlet to the sea, and the numerous towns in the cotton-growing deltas of the Al-Qāsh and Barakah rivers. With few exceptions, all major towns in The Sudan lie along one of the Niles.

Khartoum, the smallest of the states, contains the Three Towns of Khartoum: Khartoum, Omdurman, and Khartoum North. By the early 1980s the population of the Khartoum metropolitan area had grown to about one-twelfth of the country's population. The easily defended site of Khartoum was adopted by the Egyptian-Ottoman government as the colonial capital of the Sudan in the 1830s. Today it is firmly established as the centre of both government and commerce in the country. Omdurman, formerly the capital of the Mahdist state in the Sudan, retains a more traditional atmosphere, while Khartoum North is a new, industrially oriented town.

The people (Sudan, The)

Ethnic structure

One of the most striking characteristics of The Sudan is the diversity of its people. The Sudanese are divided among 19 major ethnic groups and about 597 subgroups and speak more than 100 languages and dialects.

Muslim peoples

A major cleavage exists between the northern and the southern parts of the country. The north is dominated by Muslims, most of whom speak Arabic (Arab) and identify themselves as “Arabs,” while the people of the south are “Africans” (i.e., blacks) who for the most part follow traditional African religions, though there are also some Christians among them. Those who identify themselves as Arabs were estimated at 39 percent of the total population in 1956. The largest non-Arab ethnic group is that of the Dinka, who constituted 12 percent of the population, followed by the Beja at 7 percent. (These figures are estimates, since the only census that recorded ethnicity was taken in 1956.) Moreover, ethnic identity may not actually coincide with a particular racial character. Those Sudanese who consider themselves Arabs are, for the most part, ethnically mixed, and many of them are physically indistinguishable from dark-skinned southerners. Despite a common language and religion, the “Arabs” do not constitute a cohesive group: they are highly differentiated in their mode of livelihood and comprise city dwellers, village farmers, and pastoral nomads. The Arabs have historically been divided into tribes based on presumed descent from a common ancestor. The tribal system has largely disintegrated in urban areas and settled villages, however, and retains its strength only among the nomads of the plains who raise cattle, sheep, and camels. Each Arab tribe or cluster of tribes is in turn assigned to a larger tribal grouping, of which the two largest are the Jalayin and the Juhaynah. The Jalayin encompasses the sedentary agriculturalists along the middle Nile from Dunqulah south to Khartoum and includes such tribes as the Jalayin tribe proper, the Shāyqīyah, and the Rubtab. The Juhaynah, by contrast, traditionally consisted of nomadic tribes, although some of them have now become settled. Among the major tribes in the Juhaynah grouping are the Shukriyah, the Kababish (Kabābīsh), and the Baqqārah. All three of these tribes are camel- or cattle-herders of the semiarid plains of the western and northeastern Sudan.

Besides Arabs, there are several Muslim but non-Arab groups in the north. The most notable of these are the Nubians, who live along the Nile in the far north and in southern Egypt. Most Nubians speak Arabic as a second language. The same applies to the Beja, who inhabit the Red Sea Hills. Although they adopted Islam, these pastoral nomads have retained their Bedawi language, which belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Another non-Arabized Muslim people is the Fur; these sedentary agriculturalists live in or near the Marra Mountains in the far west. North of the Fur are the Zaghawa, who are scattered in the border region between The Sudan and Chad.

Non-Muslim peoples

The vast majority of non-Muslim peoples in The Sudan live south of latitude 12° N, in the three southern states of Baḥr Al-Ghazāl, Aʿālī An-Nīl (Upper Nile), and Al-Istiwāʾīyah (Equatoria). The most important linguistic grouping in the south is that of the Nilotes (Nilot), who speak various languages of the Eastern Sudanic (Sudanic languages) subbranch of the Nilo-Saharan language family. Chief among the Nilotic peoples are the Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk, who together make up almost one-fifth of The Sudan's total population. The Dinka are mostly cattle-herders on the plains east of the White Nile, while the Shilluk are more settled farmers on the west bank of that river. The Nuer live farther south, east of the Mountain Nile. The Bari, another Nilotic people, live even farther south, on the Mountain Nile's upper course not far from the border with Uganda. In the southwestern part of The Sudan live a number of smaller ethnic groups who speak various languages belonging to the Adamawa-Ubangi branch of the Niger-Congo family of languages. Among these peoples are the Zande, who are scattered between The Sudan and Congo (Kinshasa). One of the most important non-Muslim peoples in The Sudan is the Nuba, who live in the Nuba Mountains north of the Nilotes. The Nuba are hill cultivators who have tended to be isolated from adjacent peoples in the Nile valley. They speak various Eastern Sudanic languages, among them Midobi and Birked, that are collectively known as Hill Nubian.

Over the years, The Sudan had attracted a great variety of immigrants, but the most important recent group are West Africans (Hausa, Fulani, and Borno), who are known collectively as the Fellata. Many of the Fellata are employed as seasonal labourers on the country's cotton farms. According to the 1955–56 census, the West Africans constituted 5 percent of the population; in the mid-1970s they were estimated at about 10 percent.

Languages

There are more than 100 languages spoken as mother tongues in The Sudan. Arabic (Arabic language) is the primary language of one-half of the population, with Dinka that of about one-tenth. Arabic is the official national language and is the most common medium for the conduct of government, commerce, and urban life throughout the country. English has been acknowledged as the principal language in the south since 1972. The languages spoken in The Sudan belong to three families of African languages: Afro-Asiatic (Afro-Asiatic languages), Nilo-Saharan (Nilo-Saharan languages), and Niger-Congo (Niger-Congo languages). The most important Afro-Asiatic languages are Arabic and the Bedawi language of the Beja. The Nilo-Saharan languages, including Dinka, Nuba, Nuer, and Shilluk, account for the next largest number of speakers. The Niger-Congo family is represented by the Banda, Sere, Zande, and many other smaller ethnic groups. To surmount these language barriers, the vast majority of Sudanese have become multilingual, with Arabic and, to a lesser extent, English as second languages.

Religions

It is estimated that more than one-half of the population of The Sudan is Muslim (Islāmic world). Ninety percent of these people live in the northern two-thirds of the country.

The Muslims of The Sudan belong overwhelmingly to the Sunnite (Sunnī) sect. Sunnite Islam in The Sudan, as in much of the rest of Africa, has been characterized by the formation of tariqas, or Muslim religious brotherhoods. The oldest of these tariqas is the Qādirīyah, which was introduced to the Sudan from the Middle East in the 16th century. Another major tariqa is the Khatmīyah, or Mīrghanīyah, which was founded by Muḥammad ʿUthmān al-Mīrghanī in the early 19th century. Perhaps the most powerful and best organized tariqa is the Mahdīyah (Mahdist); its followers led a successful revolt against the Turco-Egyptian regime (1821–85) and established an independent state in the Sudan that lasted from 1884 to 1898. The Mahdīyah and Khatmīyah tariqas formed the basis for the political parties that emerged in the Sudan in the 1940s and have continued to play a dominant role in the nation's politics in the postindependence period.

At least one-third of The Sudan's population follow traditional animist (animism) religions, particularly in the south and in the Nuba Mountains. Although these animists share some common elements of religious belief, each ethnic group has its own indigenous religion. Virtually all The Sudan's traditional African religions share the conception of a high spirit or divinity, usually a creator god. There exist two conceptions of the universe: the earthly and the heavenly, or the visible and the invisible. The heavenly world is seen as being populated by spiritual beings whose function is to serve as intermediaries or messengers of God; in the case of the Nilotes, these spirits are identified with their ancestors. The supreme deity is the object of rituals using music and dance.

Christians account for between 4 and 10 percent of the population. Christianity first came to the Sudan about the 6th century AD, and for centuries thereafter Christian churches flourished in the ancient kingdom of Nubia. But, after the establishment of Muslim rule in Egypt and later Arab migrations into the Sudan, Christianity declined in Nubia and was gradually replaced by Islam; the process was complete by the end of the 15th century. Christianity in the present-day Sudan is a product of European missionary efforts that began in the second half of the 19th century. Most of these efforts were concentrated in the south and in the Nuba Mountains, rather than among the Muslims of the north.

Demographic trends

In 1955–56, when the first census was taken, The Sudan's population was 10.3 million. The 1973 census gave a total population of almost 15 million, which rose to 20 million in the census of 1983. Despite the ravages of civil war and natural disasters, the country's population growth rate has averaged about 3 percent a year, bringing the total to an estimated 34.5 million in 1999. This figure leaves The Sudan with a rather low population density as a whole, but, owing to the lack of adequate water supplies in many parts of the country, half of the population lives on just over 15 percent of the land. The greatest population densities are found along the Nile rivers and their tributaries, where water is available for irrigated farming. By contrast, one-quarter of The Sudan is virtually uninhabited, including the deserts of the north and northwest.

There has been considerable rural-to-urban migration in The Sudan in the decades since independence; the urban population increased from 8.3 to 18 percent of the total between 1956 and 1972, and the fraction of the population that is urban is probably more than one-third today. It is estimated that almost five million people, more than 15 percent of the population, may now live in the capital city—i.e., the Three Towns of Khartoum, Omdurman, and Khartoum North. Recurrent famine and a continuing civil war have brought more than three million southern and western Sudanese to the capital since 1983; many of these people live in shantytowns on the outskirts of the Three Towns.

Owing to the prevalence of pastoral livelihoods, the Sudanese population is highly mobile, and about 10 percent of the population still follows a totally nomadic life-style. In addition, before the civil war, almost one million herdsmen practiced transhumance, following the northward movement of the summer rains in search of new pastures for their livestock. There are also about 500,000 seasonal labourers who move among the country's major irrigated agricultural projects.

The economy

The Sudan is one of the poorest and least developed countries in the world, with most of its inhabitants dependent on farming and animal husbandry for their livelihoods. Though its role in the economy has declined in the decades since independence, agriculture still accounts for one-third of The Sudan's gross domestic product (GDP) and more than nine-tenths of its exports, while providing the livelihood of two-thirds of the population. The economy has steadily declined since the late 1970s, when the failure of an ambitious development program left the country with both stagnating agricultural production and a large foreign debt.

Agriculture

The Sudan's main crops are cotton, peanuts (groundnuts), sesame, gum arabic, durra (a type of sorghum), sugarcane, coffee, and dates. The main subsistence crops are durra and millet, with smaller amounts of wheat, corn, and barley. There are four distinct subsectors in Sudanese agriculture: modern irrigated farming, most of which is carried out with mechanized equipment on a large scale with the help of government investment; mechanized rain-fed crop production; traditional rain-fed farming; and livestock raising.

Mechanized agriculture

Irrigated areas along the White and Blue Niles produce the bulk of the country's commercial crops. These areas are centred on the Gezira Scheme (Al-Jazīrah)—with its Mangil extension—between the Blue and White Niles south of Khartoum. Other major farming areas are watered by the Khashm Al-Qirbah Dam on the ʿAṭbarah River and by the Ar-Ruṣayriṣ Dam, which provides irrigation water for the Rahad Scheme.

The Sudan's irrigated agriculture is thus dependent on abundant supplies of water from the two main branches of the Nile. The future growth of Sudanese agriculture, however, continues to depend on mechanized rain-fed farming in a broad belt running from Ash-Sharqīyah state in the east to southern Kurdufān state in the west. One of the major disadvantages of this type of agriculture, however, is that rich farmers practice a sophisticated version of traditional shifting cultivation—they farm an area intensively with government-financed equipment for a few years but then move on to more attractive virgin land when yields decline. This practice has led to soil erosion and even to desertification in some areas.

Because of the relative anarchy of the mechanized rain-fed sector in agriculture, planners in The Sudan have tended to concentrate their efforts on irrigation schemes, under which cotton is the dominant crop. The bulk of the cotton crop is grown on the Gezira Scheme, situated on a fertile, wedge-shaped clay plain lying between the White and Blue Niles south of Khartoum. The scheme, which was begun by the British in 1925 to provide cotton for the textile mills of Lancashire, Eng., is one of the largest irrigation projects for agriculture in the world. It covers an area of 2.5 million acres (1 million hectares) and provides water for more than 100,000 tenant farmers. The tenants farm the land in cooperation with the government and The Sudan Gezira Board, which oversees administration, credit, and marketing. Although The Sudan's total output accounts for only a tiny percentage of world production, its importance in the cotton market results from supplying a large part of the extra-long-staple cotton grown in the world. In the mid-1970s there was a short-lived experiment to turn the Gezira's production away from cotton into wheat, peanuts, and other cash crops that could be used to satisfy The Sudan's domestic demand for food. This led to a dramatic fall in cotton production and export revenues, however, and in 1978 it was decided to halt this venture and return to concentration on cotton production.

The Sudan has great agricultural potential, with an estimated 210 million acres of arable land, of which less than 15 percent is under cultivation. The remainder is unused owing to inadequate water sources and transport difficulties. The Sudanese government tried to tap this potential in the 1970s, when vast projects financed by oil-rich Arab countries were undertaken in an effort to transform The Sudan into a major food producer for the Middle East. The resulting capital-intensive projects, including the building of new sugar refineries and a trunk road system, foundered owing to poor planning and government inefficiency and corruption. By the early 1980s The Sudan found itself saddled with a large foreign debt, declining agricultural production, and little capital left to invest in the country's traditional irrigated infrastructure and its network of railways, which transported its cotton and other exports. The government has since continued to try to diversify its export-based agriculture with some success, however, encouraging the production of gum arabic and sesame in an effort to reduce reliance on cotton alone.

Mechanized rain-fed farming was begun in the fertile clay plains of the eastern Sudan in the mid-1940s and has since greatly expanded. Despite the problems of irresponsible use and soil depletion mentioned previously, the broad belt of mechanized farms stretching from the ʿAṭbarah River in Ash-Sharqīyah state west to the Blue Nile is now the granary of the country, with sorghum, sesame, and cereal grains its main crops.

Subsistence farming and livestock raising

There is little development of commercial agriculture in the southern Sudan, where subsistence farming still predominates. Indeed, about two-thirds of the country's population is still engaged in subsistence farming. Besides the south, many such farmers live in the low-rainfall savannas of the central and western Sudan, growing crops of sorghum and millet.

One of The Sudan's most underestimated resources is its livestock, the commercial exploitation of which only truly began in the 1970s. The Nilotic peoples keep millions of head of cattle, while the Baqqārah and other Arabs raise similar numbers of sheep, goats, cattle, and camels. Inadequate transport facilities hinder the export of much of this livestock for sale abroad, however, and the Nilotes tend to accumulate cattle rather than sell them, viewing their herds as sources of social prestige and status rather than as disposable economic assets.

Other cash crops

Projects for the cultivation of such tropical crops as coffee, tea, and tobacco have begun in the south. Fruits grown include dates, mangoes, guavas, oranges, and bananas, while onions are the most widespread vegetable.

The Sudan is the world's largest producer of gum arabic, a water-soluble gum obtained from acacia trees and used in the production of adhesives, candy, and pharmaceuticals. The southern forests yield hardwood timber such as mahogany and sant (a type of acacia) and softwoods. The northern woodlands have been deforested by the extraction of wood for fuel and charcoal.

The Nile rivers are the main source of fish, especially Nile perch. Most of the catch is consumed locally, although attempts have been made to export fish to Europe and the Middle East. Significant quantities of fish and shellfish are produced from the Red Sea.

Industry

The Sudan's manufacturing sector remains relatively small; manufacturing and mining combined contribute less than one-tenth of the GDP and employ only 4 percent of the country's labour force. The Sudan faces severe shortages of trained manpower and raw materials, as well as of the foreign exchange that is vitally needed to import intermediate goods for its industrial sector to process. The country's industrial base is dominated by the processing of food, beverage, and tobacco products. Sugar refining is a major activity, as are the production of vegetable oil and of soap. The ginning of cotton and the production of cotton textiles also remain a major sector, though textile production has plummeted since the country's debt crisis began in the late 1970s. Other industries include the production of shoes, chemical fertilizers, and cement. Falling production elsewhere, particularly in the food-processing and textile industries, have encouraged a breaking off of state-owned factories to private interests. Such measures have had little positive effect, however, and many factories in the country operate at a mere fraction of their capacity. There are other serious problems, one of which has been a loss of trained manpower through emigration to the oil-rich countries of Arabia and the Persian Gulf. Remittances by Sudanese émigrés form an important source of income for some parts of the country, but the loss of skills has produced chronic personnel crises in a number of programs and projects.

One area of continuing optimism for the economy as a whole is that of oil (petroleum). Oil was first discovered in the southwestern Sudan in 1977, and a commercially viable find was made in 1980. The Sudan's recoverable oil reserves totaled 500 million barrels in the early 1990s, though the actual total may be substantially higher. The continuing civil war in the south has prevented any exploitation of the oil deposits, however.

About one-half of The Sudan's electricity is produced by hydroelectric plants and one-half by thermal power plants. The Sennar Dam (Sannār Dam) on the Blue Nile supplies electricity to the Gezira and to Khartoum, and hydroelectric dams have also been built at Khashm Al-Qirbah on the ʿAṭbarah River and Ar-Ruṣayriṣ on the Blue Nile.

Finance and trade

All banks operating in The Sudan were nationalized in 1970, but foreign banks were again allowed to operate after 1975. The Bank of Sudan issues all currency and acts as banker to the government. The banking system is geared primarily to the finance of foreign trade and especially the cotton trade. Most banks are concentrated in Khartoum and the surrounding area. Under the current government, banks using Islāmic banking principles have rapidly achieved a dominant position within the finance sector and a large degree of control over the country's trade. In 1990 the Bank of Sudan announced its intention to Islāmize the country's entire banking system.

The foundering of the large-scale development projects undertaken in the 1970s left The Sudan unable to pay off its loans to its Arab and other foreign creditors. The national debt more than quadrupled in the 1980s to reach about $13 billion by 1990. Merely servicing this debt takes most of the foreign exchange earned by exports, thus depriving The Sudan of much-needed capital with which to maintain its infrastructure and industries.

The Sudan suffers from an unfavourable balance of trade. Its chief exports are cotton, gum arabic, millet, sorghum, and sesame, while its chief imports consist of oil and petroleum products, motor vehicles and machinery, and wheat. Saudi Arabia has become the leading market for Sudanese exports, consuming livestock, cereal grains, and other foodstuffs. Japan, Thailand, and Italy are among the major purchasers of Sudanese cotton. The Sudan in turn receives the bulk of its petroleum from Saudi Arabia, while importing much of its machinery from members of the European Community as well as from the United States.

Administration of the economy

Government control of the economy has been gradually relaxed since the mid-1970s. This has resulted in the liberalization of exchange controls, encouragement of private and foreign investment, payment of market prices to farmers, and a number of other measures designed to cause the economy to be regulated more by the market rather than by the government.

Since 1978 The Sudan has been operating under an austerity program designed to improve the balance of payments and cut back development spending. Negotiations have periodically been undertaken to reschedule debts to external creditors, but by the early 1990s The Sudan was unable to meet even the interest payments on its burdensome foreign debt.

Little government revenue is raised by direct taxation, while indirect taxes, such as those on imports and excise and consumption duties, provide more than half the revenue. Other revenue has traditionally been derived from government monopoly profits on sugar, tea, coffee, and salt and proprietary receipts from agricultural and other schemes.

The smallness of the industrial sector and the predominance of rural life have tended to constrain the development of workers' and employers' associations. In 1989 all trade unions (organized labour) were dissolved by the new government headed by the Revolutionary Command Council.

Transportation

The transport system is underdeveloped and is a serious constraint on economic growth. The country's vast area and the availability of only one major outlet to the sea place a heavy burden on the limited facilities, especially on the government-owned Sudan Railways and on the country's growing road network. The railways had traditionally hauled most of The Sudan's freight, but heavy investments in roads (and accompanying neglect of the rail infrastructure) in the 1970s and '80s encouraged a growing reliance on trucks and other motor vehicles to haul the nation's raw materials. The road system now handles more than 60 percent of the nation's freight traffic.

There were fewer than 240 miles of paved roads in The Sudan in 1969, but by the mid-1980s this total had increased to more than 1,240 miles. By far the most important road is the all-weather highway running for 744 miles from Port Sudan to Khartoum, which was completed in 1980.

The main railway line runs north from Al-Ubayyiḍ (El-Obeid) via Khartoum to Lake Nasser and the submerged terminal of Wadi Ḥalfāʾ, with branch lines from Sannār and ʿAṭbarah to Port Sudan and from Sannār to Ar-Ruṣayriṣ. There is also a westward extension from Al-Ubayyiḍ to Nyala, with a branch line south to Wāw.

For centuries the Nile was the riverine highway of the Sudan, and the White Nile is still an important link with the southern region. The White Nile and the Baḥr Al-Ghazāl are navigable throughout the year, but the Blue Nile is not navigable, and the Nile below Khartoum is navigable only in short stretches. The government operates steamer services on the White and the main Nile. Port Sudan, 850 miles south of Suez, Egypt, is the country's main port on the Red Sea.

The government-owned Sudan Airways operates domestic and international services from the main airport at Khartoum. There are several subsidiary airports, the most important of which are those at Al-Ubayyiḍ and Port Sudan.

Administration and social conditions

Government

Since independence in 1956, The Sudan has witnessed several constitutions and regime changes, including military coups in 1985 and 1989. On seizing power in 1989, the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) for National Salvation abolished the transitional constitution of 1985, the National Assembly, and all political parties and trade unions and ruled by decree.

The RCC disbanded in 1993, after appointing ʿUmar Ḥasan Aḥmad al-Bashīr (Bashir, Omar Hassan Ahmad al-) to the position of president in the new “civilian” administration; he later retained that position by winning elections in 1996 and 2000. A new constitution, promulgated in 1998, called for Islamic law ( Sharīʿah) to be the basis for the country's laws and regulations. Under the constitution, the president is popularly elected to serve a five-year term and appoints the members of the Council of Ministers. Legislative power is unicameral, vested in the National Assembly. Members serve four-year terms; the majority are directly elected, and the remaining members are elected by specific interest groups. For administrative purposes, The Sudan is divided into 26 states, each administered by a governor.

Civil justice is administered through the Supreme Court, appeals courts, and courts of first instance. There is also a Constitutional Court. Muslims remain subject to Islamic law, as do constituents in northern states of the country regardless of their religious belief. Southern states—with a primarily animist-Christian population—are exempt from much, but not all, of Islamic law.

Multiparty politics, banned after the 1989 coup, were reintroduced in 1999. The National Congress party (formerly the Islamic National Front; NIF), long the only legal party, continued to dominate the political scene in the years immediately following. Other political associations active in The Sudan include the Ummah Party (UP), the Alliance of the People's Working Forces (APWF), the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM), and the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), an association of several opposition movements.

The Sudan's armed forces have been greatly expanded since 1969, mainly to cope with the continuing rebellion in the south. By the early 1980s the forces consisted of an army, a navy, and an air force. In 1990–91 the government began to establish a militia and also instituted a military draft to furnish recruits to conduct the war.

Education

A modern educational system was established in The Sudan in the 1970s when the government reorganized a haphazard system of schools inherited from the British colonial government. In the Muslim areas of the north, boys were long instructed in religious subjects according to traditional methods. Primary education was begun by the British in the northern Sudan after 1898, and secondary education began in 1913. The University of Khartoum was formally established in 1956 from the University College of Khartoum, which itself dated from the merger in 1951 of two smaller colleges founded by the British.

Christian missionaries assumed responsibility for formal education in the south prior to independence. Southern education suffered during the subsequent civil war; the national authorities curtailed missionary activities, attempted to Arabize the southern schools, and, failing that, closed them in 1962. The southern partisans operated schools in the areas they controlled, but their resources were extremely limited.

After being extensively reorganized in 1969 and in the 1970s, the Sudanese educational system was reorganized yet again in 1992. Under the new system, eight years of primary education (later made compulsory in 1998) begin at age six. Three years of secondary education—either academic or vocational in nature—then follow. The primary language of instruction in the nation's primary schools is Arabic.

In addition to the University of Khartoum, higher education is provided by several universities, including Omdurman Islamic University, which trains Muslim clerics and scholars, and Ahfad University for Women, also in Omdurman. National universities that emphasize scientific and technical training were opened in the 1970s at Wad Madanī and at Juba. Between 1990 and 1995, the number of universities in The Sudan more than doubled—the result of government efforts to expand opportunities for higher education. English was formerly the medium of instruction in the nation's universities and secondary schools but has now been largely replaced by Arabic. The south, ravaged by decades of civil war, remains the most educationally deprived region of the country. Literacy rates in The Sudan, although showing improvement since independence, are still relatively low when compared with the rest of the world: about three-fifths of adults are able to read.

Health

Varying ecological conditions in The Sudan, poor hygiene, and widespread malnutrition result in a high incidence of fatal infectious diseases. The most common illnesses are malaria, measles, and tuberculosis. Cerebrospinal meningitis, whooping cough, and infectious hepatitis are not uncommon. Schistosomiasis (bilharzia), leishmaniasis, dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease), and African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) are endemic in the southern part of the country.

Many Sudanese in rural areas suffer from temporary undernourishment on a seasonal basis. Malnutrition is prevalent year-round in Darfur and in the south, especially among children, because of the disruptive effects of the civil war. Life expectancy for both men and women in The Sudan is below the average for North Africa, and the infant mortality rate is significantly higher.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the Ministry of Health initiated a national program intended to provide primary health care throughout the country, with an emphasis on preventive medicine. A lack of funds severely affected the plan's implementation, as it would the government's establishment in the early 1990s of three tiers of health care at the federal, state, and local levels.

At the beginning of the 21st century, roughly half of all Sudanese had access to health services, but accessibility greatly depended upon geographic location. Most of the country's small number of physicians are concentrated in the urban areas of the north, as are the major hospitals. Medical assistants, who can diagnose common endemic diseases and provide simple treatment and vaccination, are in short supply and tend to work in the north, as do most trained nurses and midwives. International relief agencies have made efforts to expand health care access in the non-government-controlled areas in the south.

Traditional cultures

Because of The Sudan's great cultural diversity, it is difficult to classify the traditional cultures of the various peoples. These traditional societies have diverse linguistic, ethnic, social, cultural, and religious characteristics. And, although improved communications, increased social and economic mobility, and the spread of a money economy have led to a general loosening of the social ties, customs, relationships, and modes of organization in traditional cultures, much from the past still remains intact. The selection of four cultures that follows merely suggests some rather prominent cultural patterns that are illustrative of the wide range present. These four cultures are those of the Azande (Zande), African animists of the southwestern Sudan; the Fur, Muslim Africans in the far western part of the country; the Humr tribe of the Baqqārah Arabs, of the west-central Sudan; and the Otoro tribe of the Nuba, in the east-central Sudan.

Social organization

Political and territorial organization

Broadly speaking, the traditional societies of The Sudan exhibited two types of political organization: the hierarchical systems of the Azande and Fur and the segmentary systems of the Humr Baqqārah and Otoro. Zandeland, for example, was divided into a number of autonomous chiefdoms (chief). The structure of authority within each chiefdom was pyramidal, with chiefs (previously kings) at the apex of the hierarchy, followed by subchiefs, deputies, and finally homestead heads. The homestead was the basic political, social, and economic unit. Absolute authority lay with the aristocratic Avongara clan, and commoners could reach only the positions of deputy or homestead head. Local groupings, in which descent was reckoned in the male line, were not associated with clans or sections of clans; they were political and administrative units. Clans had little corporate life, and genealogical links between clansmen were seldom known.

A centralized political and administrative structure also existed among the Fur. There was a sultan at the head of the state, which was divided into four regions in turn divided into districts, subdistricts, and villages. Each village had a council of elders who decided minor cultivation disputes and enforced their decisions by advice and warning. The rights of the village were vested in its inhabitants jointly. Ultimate authority lay with the sultan, who could depose officials beneath him when their power became a threat to his dominance.

In contrast, the Humr Baqqārah had a political system based on a segmentary lineage organization. The tribe was divided into two sections, each of which was divided into a further five sections, each comprising major lineages, camps, and extended families. All these groups had potential leaders. The significant residential and herding unit was the camp, the composition of which changed with the seasons. Within each tribe and at every level, there was a process of splitting, migration, and resettling that resulted in a continuous change of alliance among groups and individuals. Blood feuds occurred between segments and were settled by payment of blood money. Power among the Humr Baqqārah stemmed from wealth and strength of personality.

The Otoro political system consisted of a number of territorial segments that did not coincide with kinship groupings. Clan members were scattered in different localities; the basic political unit was the hill community, whose members shared a tract of land and a common code of morality. Feuding between hill communities was constant, but members of the same hill community could not kill one another. The Otoro recognized tribal boundaries defined by periodically renewed intertribal treaties. Because of the continual raids and wars between segments, a chieftainship, with the power to use force to maintain peace, was established.

Family and kinship patterns

In all the societies descent was reckoned in the male line, but the significance of such agnatic ties among kin groups differed from one society to another. Among the Azande there were exogamous clans that functioned primarily as political and administrative units. Clan members were expected to join together to celebrate births, marriages (marriage), and funerals. The Azande recognized obligations to the kin of both parents, but greater importance attached to the paternal connection. Until an Azande male married, he had not achieved a man's full status. Marriage was a series of events, each of which was marked by the transfer of goods from one group of kin to the other. Wives of a dead man were inherited by his sons or brothers. polygyny was also practiced and was regarded as a means of extending affinal (in-law) relationships and acquiring support. Although divorce is now common, a broken marriage was considered a shameful thing because it destroyed the network of relationships.

The Fur also reckoned descent patrilineally, but residence was customarily with or near the wife's parents. However, if a husband disagreed with his in-laws, he could take his wife to live with his own group. Cousin marriage, sororate (customary marriage with a deceased wife's sister), levirate (customary marriage to an elder brother's widow), and polygyny were practiced.

Among the Humr Baqqārah, members of the smallest lineage (surra), together with their dependents, formed a single camp. The organization of a surra depended on the number of cattle and the distribution of their ownership among its members. Each surra had a leader who was wealthy but who had no administrative functions unless he was already a member of the local government. Whereas members of a camp formed the basic unit of cooperation over herding, the household was the main unit of cooperation in agriculture, although some activities connected with agriculture involved a wider group. Preferred marriage within the surra was with a parallel cousin. Many first marriages, contracted to conform to the expectation of elders, ended in divorce, but in subsequent marriages partners could be freely chosen.

Among the Otoro there were patrilineal clans of various size. With the exception of the Chungur clan, which was the traditional holder of the hereditary chieftainship, all clans were socially of equal order. Clan members intermarried with each other, although clan exogamy was formerly the rule. In the economic and religious spheres the clan did not exercise influence, but it did impose upon its members the collective duty of blood feud in the case of homicide between clans. Patrilineal descent was important in determining the social identity of a person, inheritance, and rights and duties concerning marriage and bridewealth (gifts from the groom and his kinsmen to the father of the bride and his kinsmen). Although the Otoro were patrilineal, matrilineal ties were also important. Polygyny and leviratic marriages were practiced, and bridewealth payments established wider contact between social groups. Divorce was negotiated and settled by the families concerned. The marriage was usually dissolved by the total refund of the bridewealth to the former husband.

Social stratification

All the groups had some form of class distinction. The Azande's Avongara clan recognized rigid distinctions between chiefs and commoners, and, generally, among the Azande there were distinctions between conquering and conquered groups and slaves. Political, economic, and social status depended exclusively on birth, but the politically superior group, the Avongara, had to maintain their position by organized political and military means.

The highest political office among the Fur was that of the sultan, who was surrounded by a body of councillors dependent on royal patronage. Locally, there was a descending hierarchy of hereditary fief stewards, village heads, and, lastly, heads of households. Ironworkers were a despised class not allowed to intermarry with ordinary Fur.

Among the Humr Baqqārah, the main distinction was between persons of Arab descent (who held the positions of power) and non-Arabs. In other respects, a person's wealth and personality determined his successful bid for leadership.

Traditionally, among the Otoro there were no political offices, only a special hereditary ritual office—that of “chief of the Path,” who acted as intermediary in peace negotiations between conflicting parties. Today, however, there are chiefs selected by the local government from among persons of local wealth and importance. In addition there were age-grades (age set); membership in each of the five grades lasted three years, after which all the members were promoted together to the next higher grade. Promotion was marked with festivities, and members of each age-grade lived separately. This system marked the development of a person from an ordinary youth to that of a “big man.” Girls also formed age-grade groups.

Socialization and education

In all societies under comparison, there were ritual and ceremonial practices marking the stages in the life cycle of the individual—birth, circumcision, puberty, marriage, and death. Circumcision distinguished boyhood from manhood. It was a recent introduction among the Azande, having spread from the south despite being opposed by the Avongara. Among the Otoro, an individual achieved higher status as he was promoted from one age-grade to another. There was also an association of cicatrization (scarring) with a test of manhood: killing an enemy entitled a person to have a small pattern of scars on his back. Similar patterns were also made on the upper arms of successful hunters. Men took part in wrestling and fighting as part of their training for manhood.

There was little formal education among the Azande, Otoro, Humr Baqqārah, and Fur. Among the Azande and Nuba, there were very few schools at the elementary level established by missions. Education made little headway among the Humr Baqqārah because it came into conflict with their way of life—people were reluctant to send their children to schools because livestock and cattle herding would suffer. There were a few Qurʾānic schools among the Fur, in which elementary Arabic, arithmetic, and the Qurʾān were taught.

Economic organization

Settlement patterns

The societies exhibited three different patterns of settlement. The Otoro and Azande lived in scattered groups. Otoro homesteads were scattered irregularly over hilltops and valleys, a number of homesteads constituting a village, villages combining to form hill communities, a number of which made up the tribe. Similarly, the Azande lived in family groups in scattered homesteads separated by strips of bush. Among the Otoro and the Azande, the homesteads were the basic social and economic unit. In contrast, the Fur had more compact settlements. The Fur lived in homesteads, a number of which constituted a village. The third type of settlement pattern was that of the Humr Baqqārah, who lived in tent camps. Their nomadic existence did not permit the formation of permanent settlements.

Production and technology

The economy of most of the peoples of The Sudan was and still is dependent on cultivation, with animal husbandry, and sometimes hunting and fishing, providing an important supplement to agriculture. A wide variety of crops are grown, including grain, sesame, vegetables, sorghum, corn (maize), peanuts (groundnuts), and cotton, the latter two sometimes as cash crops. Among the Humr Baqqārah cultivation is a subsidiary occupation. They move in a regular seasonal cycle according to the availability of water and grass. In winter, or at the end of the rains, they move south, and in spring, or during the rains, they move north. Some cultivation of millet and of cotton as a cash crop is undertaken. Throughout their territory the Humr Baqqārah have communal grazing rights, whereas cultivable plots of land are owned individually and handed down from father to son.

The technology of these societies was formerly simple. Among the Otoro the making of bedsteads, mat weaving, and pottery were undertaken. The Azande, on the other hand, were prominent as craftsmen and artists. Their superior material culture, particularly their knives, spears, and shields, was one of the factors by which they dominated their neighbours and brought about the spread of their culture. Basketry, net weaving, pottery, smelting, metalworking, and ivory and wood carving also were undertaken. There were ironworkers in every Fur village; other Fur crafts included tanning and weaving of cloth and basketry. The Humr Baqqārah produced leather goods and basketry to meet their own needs.

Property and exchange systems

Land among the Otoro, Azande, and Fur was the principal economic asset. Among the Otoro, land could be acquired through inheritance, purchase, and lease and by clearing and cultivating new areas. The Otoro and the rest of the Nuba tribes converted nearly their whole agricultural surplus into livestock. Although livestock were used for clan sacrifices, they were not sold for money, and neither were they slaughtered for meat. Among the Nuba tribes, however, people used livestock for certain standardized payments such as bridewealth or gifts to kin relations. Iron, because of its rarity and its use in weapons and tools, became the standard medium of exchange. Handicraft products were purchased with such goods as grain, sesame, hoes, spears, goats, and axheads, and, nowadays, with money.

Whereas livestock is a secondary source of wealth to the Otoro, cattle are the primary source of wealth, prestige, and political position for the Humr Baqqārah. Cattle were once the medium of exchange, but during the 20th century cash became significant.

Before the introduction of cotton and money, wealth among the Azande was primarily in the form of perishable agricultural produce, and it was customary to destroy the property of a man after his death. Only chiefs were able to accumulate wealth, since they received tribute and prisoners of war as perquisites. There was little exchange between households, although iron tools and spears were used in bridewealth payments.

Among the Fur, property consists of houses, domestic articles, rolls of cloth, and cattle kept mainly for resale. Rights over land are held jointly by descent groups and are vested in a titleholder. There are organized marketplaces in which the medium of exchange has been, and still is, money. Previously, cloth may have served as a medium of exchange. Agricultural products are exchanged for tools and utensils, cloth, and other commodities. Labour is exchanged for beer.

Religious practices

The Humr Baqqārah and Fur peoples adhere to Islamic beliefs and practices, which came to them through Arab influence, and traditional local practices coexist with Islamic beliefs. Among the Fur, for example, the splashing of sanctuaries with a flour-and-water paste is carried out to ensure fertility. There are also rain (rainmaking) cults thought to have been introduced from farther west. Sacrifices are made at shrines and at ancestral tombs when the rains are likely to fall. The office of rainmaker is hereditary.

The Otoro and Azande have their own local beliefs and practices, which are significant as a means of social control, and Islam and Christianity have very little influence. Among the Otoro there is a widespread belief in oracles (oracle) and witchcraft as a means of punishing offenders and establishing justice. Charms bought from Arab or West African charm sellers, diviners, grain priests, and rainmakers are used to find and punish evildoers. leprosy, imagined to be caused by supernatural powers, is believed to be connected with offenses such as sexual intercourse in forbidden kinship degrees and homicide. Witchcraft, a magic at the disposal of any individual, is effective only if directed against a person guilty of a crime.

Among the Azande the power of witchcraft is inherited. Diviners, oracles, vengeance magic, and the use of leeches are means of counteracting it. The Avongara clan may not be accused of witchcraft because the chief and his oracle are considered infallible.

Cultural life

The key to an understanding of contemporary Sudanese culture is diversity. Each major ethnic group and historical region has its own special forms of cultural expression, and the linguistic diversity of the country provides the basis for a richly varied written and oral literature.

One of the most important forms of cultural expression among nonliterate groups is oral tradition. The major language with a written literature in traditional Sudanese society is Arabic. The most widely known Sudanese literary works in this language are associated with Islām and its scholarship and include a large body of literature describing the lives and virtue of holy men. These works are best known through recitations on special anniversaries associated with pious persons. In the 20th century, the combination of oral and written literature remains of major importance to both traditional and Westernized segments of Sudanese society. Perhaps the best-known Sudanese novelist is aṭ-Ṭayyib Ṣāliḥ (Ṣāliḥ, al-Ṭayyib), whose books Season of Migration to the North and The Wedding of Zein have been translated into foreign languages.

Poetry is another important form of literary expression. Modern Sudanese poetry reflects the mixed African and Arab cultural heritage of the country, as expressed in the works of Muḥammad al-Mahdī al-Majdhūb and many others.

In such arts as painting, weaving, and pottery making, each locality has developed unique forms and styles. However, in the 20th century, more unified national styles have emerged under the influence of artists in the cities. The College of Fine and Applied Arts within the Khartoum Polytechnic has served as the home of graphic arts in The Sudan, and a number of Sudanese printmakers, calligraphers, and photographers have achieved international recognition. Ibrāhīm aṣ-Ṣalaḥi, who is proficient in all three mediums, is perhaps the most widely known such artist.

Song plays an important role in all the cultural traditions of The Sudan and ranges from the unique cosmopolitan traditions of Qurʾānic recitation in a melodramatic manner to tribal songs. A characteristically national style of music is emerging out of this diversity, as reflected in the music heard in Khartoum.

The Sudan is one of the richest African countries in terms of archaeological sites. The Sudan Antiquities Service manages the National Museum, a magnificent Khartoum landmark, and smaller archaeological exhibits in Marawī and Al-Ubbayiḍ. The Ethnographical Museum and the Sudan Natural History Museum are affiliated with the University of Khartoum. Drama flourishes at the National Theatre and elsewhere in Khartoum.

In view of its religious diversity, The Sudan observes both Muslim and Christian holidays. One of the most popular religious festivals is that of the Prophet Muḥammad's birthday.

Perhaps the most popular form of sports is football (soccer), and a number of clubs exist all over the country.

There are two broadcasting stations: the oldest is in Omdurman, and the other was established in Juba, the capital of the southern region, after the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement. Between 1986 and 1989 The Sudan had one of the freest presses in Africa, with more than 40 independent newspapers, but, after the June 1989 military takeover, civilian newspapers were banned, and today there are only a few state-controlled papers.

Additional Reading

General works

Harold D. Nelson (ed.), Sudan, a Country Study, 3rd ed. (1983); and John Obert Voll and Sarah Potts Voll, The Sudan: Unity and Diversity in a Multicultural State (1985), provide basic information on the land, people, economy, and history. John Mack and Peter Robertshaw, Culture History in the Southern Sudan (1982), is a collection of articles on history, archaeology, language, and culture. Further sources on all aspects of the country may be found in M.W. Daly (comp.), Sudan (1983), an annotated bibliography.

Physical and human geography

A standard text on the physical and human geography of The Sudan is K.M. Barbour, The Republic of the Sudan: A Regional Geography (1961). A.J. Whiteman, The Geology of the Sudan Republic (1971), is a comprehensive and systematic account of The Sudan's geology. Studies of the people of Sudan include Abd-al (abdel) Ghaffar Muhammad Ahmad, Shaykhs and Followers: Political Struggle in the Rufaʿa al-Hoi Nazirate in the Sudan (1974), an excellent analysis of the political and social structure of this nomadic community in the southern Funj region; Francis Mading Deng, Africans of Two Worlds: The Dinka in Afro-Arab Sudan (1978), a historical and social study of the Dinka people in the southern Sudan; Mark R. Duffield, Maiurno: Capitalism & Rural Life in Sudan (1981), a pioneering study of a West African migrant community on the Blue Nile; Wendy James, ʿKwanim Pa: The Making of the Uduk People (1979), an anthropological study of the Uduk people in the upper Blue Nile; B.A. Lewis, The Murle: Red Chiefs and Black Commoners (1972), an anthropological investigation of these southern Sudan people; and Fatima (Fatma) Babiker Mahmoud, The Sudanese Bourgeoisie: Vanguard of Development? (1984), a study that traces the roots and the development of the modern Sudanese bourgeoisie.Essays on the economy are collected in Ali Mohamed El-Hassan (ed.), An Introduction to the Sudan Economy (1976); and in Norman O'neill and Jay O'brien (eds.), Economy and Class in Sudan (1988), on political economy, emphasizing the process of class formation. On agriculture, see Tony Barnett, The Gezira Scheme: An Illusion of Development (1977), a critical socioeconomic analysis of the Gezira cotton scheme; A.B. Zahlan (ed.), The Agricultural Sector of Sudan: Policy & Systems Studies (1986); and G.M. Craig (ed.), The Agriculture of the Sudan (1991), a regional survey that also includes much information on the country's physical geography, people, economy, administrative and social conditions, and cultural life. Robert O. Collins, The Waters of the Nile: Hydropolitics and the Jonglei Canal, 1900–1988 (1990), describes the critical and sensitive relations of the riverine states over the vital Nile water. Tim Niblock, Class and Power in Sudan: The Dynamics of Sudanese Politics, 1898–1985 (1987); and Peter Woodward, Sudan, 1898–1989: The Unstable State (1990), analyze the country's government. Cultural life is explored in Muḥammad ʿAbdul-Ḥai (Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Ḥayy), Conflict and Identity: The Cultural Poetics of Contemporary Sudanese Poetry (1976), which traces the development and analyzes the different schools of modern Sudanese poetry; and Sayyid (Sayed) ĕāmid ĕurreiz and Herman Bell (eds.), Directions in Sudanese Linguistics and Folklore (1975), an introductory work on language and folklore in The Sudan, part of a conference proceedings.

- Sanatruces

- San Bernardino

- San Bernardino Mountains

- San Bernardino Pass

- San Blas

- Sanborn, Franklin Benjamin

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Carlos

- San Carlos de Bariloche

- Sancerre

- Sanches, Francisco

- Sanchez, Salvador

- Sanchez, Sonia

- Sancho I

- Sancho I Garcés

- Sancho II

- Sancho II Garcés

- Sancho III

- Sancho III Garcés

- Sancho IV

- Sancho Panza

- Sancho Ramírez

- Sancho VI

- Sancho VII

- San-ch'ung