Côte d'Ivoire

Introduction

Cote d'Ivoire, flag of

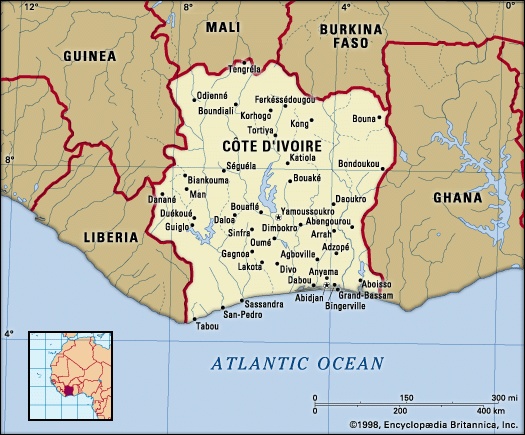

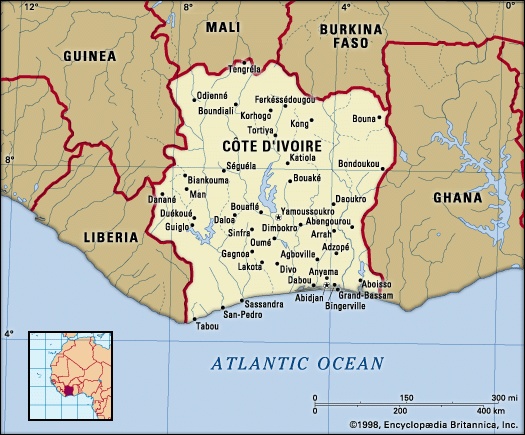

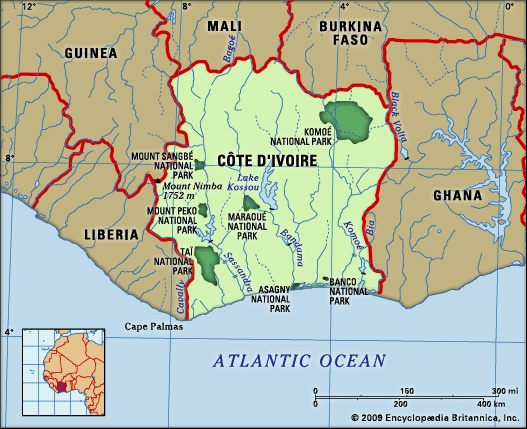

country located on the coast of western Africa. The de facto capital is Abidjan; the administrative capital designate (since 1983) is Yamoussoukro.

country located on the coast of western Africa. The de facto capital is Abidjan; the administrative capital designate (since 1983) is Yamoussoukro.

country located on the coast of western Africa. The de facto capital is Abidjan; the administrative capital designate (since 1983) is Yamoussoukro.

country located on the coast of western Africa. The de facto capital is Abidjan; the administrative capital designate (since 1983) is Yamoussoukro.Land (Côte d'Ivoire)

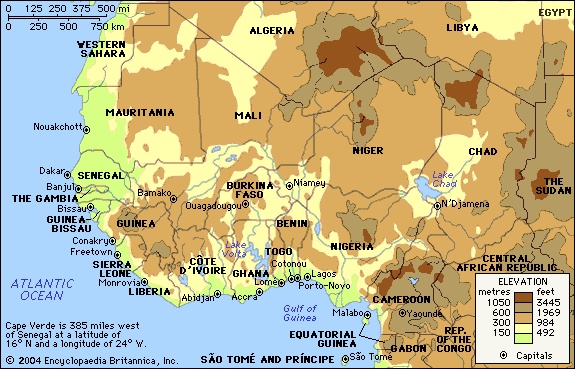

Côte d'Ivoire is bounded to the north by Mali and Burkina Faso, to the east by Ghana, to the south by the Gulf of Guinea (Guinea, Gulf of), to the southwest by Liberia, and to the northwest by Guinea.

Côte d'Ivoire is bounded to the north by Mali and Burkina Faso, to the east by Ghana, to the south by the Gulf of Guinea (Guinea, Gulf of), to the southwest by Liberia, and to the northwest by Guinea.Relief

The ground rises constantly as it recedes from the coast, and the northern half of the country consists of high savanna lying mostly 1,000 feet (300 metres) above sea level. Most of the western border with Liberia and Guinea is shaped by mountain ranges, whose highest point, Mount Nimba (5,740 feet 【1,752 metres】; see also Nimba Range), is situated in the the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve (designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981), where the borders of the three countries meet.

The ground rises constantly as it recedes from the coast, and the northern half of the country consists of high savanna lying mostly 1,000 feet (300 metres) above sea level. Most of the western border with Liberia and Guinea is shaped by mountain ranges, whose highest point, Mount Nimba (5,740 feet 【1,752 metres】; see also Nimba Range), is situated in the the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve (designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981), where the borders of the three countries meet.The country is made up of four natural regions. The coastal fringe consists of a strip of land, no more than 40 miles (64 metres) wide, studded with lagoons on its eastern half. Access from the sea is made difficult by the surf and by a long submarine sandbar. Behind the coastal fringe lies the equatorial forest zone that until a century ago formed a continuous area more than 125 miles (200 metres) wide. It has now been reduced to an area roughly triangular in shape, with the apex lying a little to the north of Abidjan and with the base lying along the Liberian border. The cultivated forest zone, which lies to the east of this triangle, consists of forest land that has been partially cleared for plantations, especially along the Ghana border and in the area around Bouaké. The fourth region, the northern savanna, consists of a sparsely populated plateau, offering open ground favourable for stock breeding. About 4,500 square miles (11,650 square km) in this region have been set aside to form Komoé National Park, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1983.

Drainage

Apart from the Cavally River (Cavalla River), which forms most of the border with Liberia, major rivers from west to east are the Sassandra (Sassandra River), the Bandama (Bandama River), and the Komoé (Komoé River), all of which drain southward into the Gulf of Guinea (Guinea, Gulf of). Because all are broken by numerous falls and rapids, their value for transportation is minimal. Their hydroelectric potential is being tapped, however.

Soils

The forest soils of the south tend to lose their fertility because of excessive leaching and turn into laterites, which contain iron oxide. The poorly drained, yellow, swampy soils, also found largely in the south, more readily maintain their fertility because of their silica and clay minerals content. Crustlike “shields,” formed as a result of rapid evaporation, alternate with rich black silico-clayey soils in the savanna areas.

Climate

Equatorial and southern savanna types of climate prevail. North of approximately 8° N latitude, the southern savanna type of climate occurs, characterized by the parching wind known as the harmattan, which blows from the northeast beginning in December and ending in February. The dry season lasts from about November to March. A single rainy season from April to October produces annual precipitation totals ranging from around 45 inches (1,100 mm) in the northeast and centre to approximately 60 inches (1,500 mm) in the northwest. The northern region is drier than the rest of the country and, because of the elevation, somewhat cooler. South of 8° N latitude, two rainy seasons occur, and three climatic subdivisions may be discerned. Rain falls largely from May through July and to a lesser extent in October and November on the coastal fringe. Abidjan receives approximately 75 inches (1,900 mm) of precipitation annually, although considerable variations are experienced at different places along the coast. Average monthly temperature variation is small, and diurnal temperatures range from around the low 70s F (low 20s C) to the low 90s F (mid-30s C). In the forest zones and in the southern part of the savanna region, the rainy seasons are less pronounced. Diurnal temperatures vary between around the low 60s and low 100s F (mid-10s and upper 30s C), and the relative humidity is often high. On the mountains farther west there is no dry season, and precipitation amounts to about 80 inches (2,000 mm).

Equatorial and southern savanna types of climate prevail. North of approximately 8° N latitude, the southern savanna type of climate occurs, characterized by the parching wind known as the harmattan, which blows from the northeast beginning in December and ending in February. The dry season lasts from about November to March. A single rainy season from April to October produces annual precipitation totals ranging from around 45 inches (1,100 mm) in the northeast and centre to approximately 60 inches (1,500 mm) in the northwest. The northern region is drier than the rest of the country and, because of the elevation, somewhat cooler. South of 8° N latitude, two rainy seasons occur, and three climatic subdivisions may be discerned. Rain falls largely from May through July and to a lesser extent in October and November on the coastal fringe. Abidjan receives approximately 75 inches (1,900 mm) of precipitation annually, although considerable variations are experienced at different places along the coast. Average monthly temperature variation is small, and diurnal temperatures range from around the low 70s F (low 20s C) to the low 90s F (mid-30s C). In the forest zones and in the southern part of the savanna region, the rainy seasons are less pronounced. Diurnal temperatures vary between around the low 60s and low 100s F (mid-10s and upper 30s C), and the relative humidity is often high. On the mountains farther west there is no dry season, and precipitation amounts to about 80 inches (2,000 mm).Plant and animal life

The tropical rainforest in the south contains valuable timber species, including African mahogany and iroko (or African teak). An important afforestation centre is Banco National Park, (Banco National Park) on the northwestern edge of Abidjan. Trees more than 150 feet (45 metres) high can be found at Taï National Park (Taï, Parc National de), which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982.

The animal life of the forest zone differs little from that of adjoining Ghana, although the larger ungulates (hoofed mammals) are lacking, with the exception of the bongo (a reddish brown antelope) and the forest buffalo. There are also several varieties of dwarf antelope, ranging from the royal antelope to the yellow-backed duiker. The giant forest hog is widespread, and the red river hog is locally plentiful. To the north the savanna woodlands have some 10 species of antelope, as well as lions and occasional herds of elephants. Komoé National Park in the northeast is well stocked with wildlife. There are lions, elephants, leopards, green monkeys, and more than 20 species of pigs. In addition, more than 400 species of birds have been identified there so far. Taï National Park, near the Liberian frontier, is notable for its pygmy hippopotamuses, and the chimpanzee population there has been the subject of a long-term study by Hedwige Boesch-Achermann and Christophe Boesch.

People (Côte d'Ivoire)

Ethnic groups

There are more than 60 ethnic groups in Côte d'Ivoire. Traditionally, the groups were independent from each other, but, over time, internal migration and extensive intermarriage greatly reduced group identity with a particular cultural tradition in any given locality. Each of these groups has ethnic affiliations with larger groups living outside the borders of the country. Thus, the Baule, as well as other peoples living east of the Bandama River, are affiliated with the Akan in Ghana, as are the lagoon fishermen farther south. The forest people west of the Bandama are connected to the Kru peoples of Liberia. In the interior the Kru group is subdivided into small groupings scattered over large areas of the forest.

The savanna peoples may be divided into two main groups. The Mande group, which is particularly strong in Mali, is represented by the Malinke farmers and by the Dyula traders. The Gur group, represented by the Senufo, Lobi, and Bobo, are widely scattered over the northeastern region and also live in neighbouring states.

Languages

All African languages represented in Côte d'Ivoire belong to one of three subgroups of the Niger-Congo family: Kwa (Kwa languages) in the south, Mande (Mande languages) in the northwest, and Gur (Gur languages) in the northeast. A trade language, known as Dyula-Taboussi and akin to the Mande Bambara, is spoken throughout the country by Muslim traders, and français de Moussa is a pidgin French widely spoken in Abidjan. The official language is French.

Religion

Traditional religions, followed by almost two-fifths of the population, continue to predominate among rural communities. Islam is followed by about one-quarter of the population, found primarily in the northwest and in Abidjan. Almost one-third of the population is Christian, mostly Roman Catholic or Methodist. Also present in the country are followers of the Harrist (Harris movement) faith, a syncretic religion (religious syncretism) indigenous to Côte d'Ivoire. Founded by William Wade Harris during World War I, it claims an estimated 100,000 adherents in the country.

Settlement patterns

Rural environment

In the southeastern quarter of the country, most people live in compact villages and towns. The entire area is divided into small states with kings and an elaborate hierarchy of ministers and palace officials, but these traditional rulers have no official standing in the modern state. Open-air markets are held in some town centres every four days. Women sell produce, as they do in many parts of western Africa. Fishermen maintain their own separate markets.

In the southeastern quarter of the country, most people live in compact villages and towns. The entire area is divided into small states with kings and an elaborate hierarchy of ministers and palace officials, but these traditional rulers have no official standing in the modern state. Open-air markets are held in some town centres every four days. Women sell produce, as they do in many parts of western Africa. Fishermen maintain their own separate markets.Among the Kru and other peoples of the southwestern forest zone, dwellings are clustered around a central open area. Women do most of the daily work, both at home and in the fields, where they grow such crops as yams—the most basic national staple—and corn (maize), cassava (manioc), and peanuts (groundnuts). The men are responsible for hunting, gathering kola nuts and oil palm nuts, and—on the coast—fishing.

The Malinke people of the northwestern part of the country are descendents of the Mali empire (Mali). Much earlier a regional revolution was created when the use of millet, still their staple food, was discovered. Other cereals such as sorghum and corn were later introduced, and cotton has been cultivated for centuries. Cattle are kept by everyone, but for purposes of prestige and for use on ceremonial occasions rather than for economic reasons. The men who raise livestock and cultivate crops may also travel extensively for trade. The village chief has authority over the population as does the traditional nobility, which comprises the chief representatives of the linear descendants of the first settlers. Some professions, such as blacksmith and griot (a historian-minstrel), are hereditary and reserved only for certain families.

The rest of the savanna is part of the domain of the Gur-speaking peoples, many of whom live in neighbouring Burkina Faso. Among them, the Senufo live immediately east of the Malinke and have adopted many Malinke customs. They live in comparatively large villages overseen by local chiefs. All other savanna communities are split into dispersed homesteads. Millet and sorghum are the staple foods, and the men do most of the agricultural field work. All the people keep cattle. The people are great traders; local market trading is conducted by women, and outside trading is conducted by the Dyula, a subgroup of the Malinke. Each community is run by the head of the main lineage group, who seeks above all to mediate in disputes so the earth may never be defiled by blood spilling.

Urban environment

Abidjan, one of the many trading ports built by Europeans along the African coast, is located on a lagoon rather than on the sea. The city is divided by a branch of the lagoon into Plateau, the first European settlement, to the north, and Treichville, the first large African settlement, to the south. Bridges connect the two areas.

Plateau was recommended for settlement as early as 1898, and Europeans began living there in 1903. Treichville, located behind the fishing village of Anoumabo, owes its importance to the boom in colonial trade that followed World War I. It remained a very small town until 1934, when the seat of colonial government was moved to Abidjan from Bingerville. Urban growth was rapid after the 1.7-mile (2.7-km) Vridi Canal opened in 1950 and provided access to the sea. Under a new era of economic expansion, Treichville gained 150,000 inhabitants and reached its population saturation point within a decade. Comprehensive planning for urban growth after 1960 was rendered impossible because of the many confining branches of the lagoon waters.

The first planned urban extension consisted of building a colonial army camp north of Plateau. Adjamé and Attiécoubé, two places with African inhabitants, offered an abundance of moderate-rent dwellings, but they rapidly deteriorated and were inconsistent in design with African traditions of family life. Across the small bay east of Abidjan, Cocody grew up in isolation as an area of expensive housing (including the presidential tower mansion) with two hotel complexes and a tourist centre.

Petit-Bassam Island, where Treichville lies, also contains the settlements of Marcory and Koumassi. Beyond them Port-Bouët grew up on the seashore, 8 miles (13 km) southeast of Plateau. Squatters helped develop Yopougon-Attié and Abobo across the bay to the west. Greater Abidjan was finally organized into 10 municipalities (each one with an elected council and a mayor) in 1986.

Demographic trends

During the latter half of the 20th century, Côte d'Ivoire had one of the highest population growth rates in sub-Saharan Africa and in the world. Its high rate of natural increase together with the huge influx of immigrants from the impoverished countries to the north, which its comparatively strong economy attracted, were the main reasons for its rapid growth. This growth rate is declining, however, in part because of the increasing number of HIV-positive people in the population.

Birth and death rates in Côte d'Ivoire are higher than those of the rest of the world. Although life expectancy in the country is average for the region, it is lower than that of the world. Côte d'Ivoire's population is relatively young, with about two-fifths under age 15.

Immigrants constitute approximately one-fourth of the total population. Nearly one-half of the population lives in urban areas, and among the urbanites there is a large French community as well as a number of Lebanese and Syrians. In the wake of the civil war that began in 2002, thousands of people fled the country and hundreds of thousands more were internally displaced.

Economy

Côte d'Ivoire had a good financial reputation for many years, but this began to change in the late 1980s, and the country experienced seven straight years of recession from 1987 to 1993. During that time the country was unable to meet its foreign debt obligations, but new financial arrangements by creditor banks and a 50 percent devaluation of the CFA franc helped the country toward economic recovery by the mid-1990s. The CFA devaluation, mandated by France, made Ivoirian exports of timber, fish, and rubber more attractive. A significant fall in cocoa and coffee prices at the end of the 20th century, however, interrupted the recovery. Political instability since the late 1990s also hindered the process.

Ivoirian financial policy is fundamentally liberal, and investments are welcomed through tax exemptions and legal protection against nationalization. Increased privatization became government policy in the mid-1980s, partly in response to the government's previous participation in too many specialized undertakings in its attempt to diversify the economy. The Ivoirian government successfully met international lender conditions for debt repayment, but it is still struggling to enact reforms in the management of its public finances and to reduce serious inequalities in the distribution of income.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Agriculture provides a livelihood for more than half the labour force, and locally grown subsistence crops meet most rural domestic needs. Urbanization and the growing use of hired labour throughout the country created a demand for foodstuffs other than yams, cassava, plantains, and corn. An acquired taste for bread and beer led to significant imports of wheat.

Agriculture provides a livelihood for more than half the labour force, and locally grown subsistence crops meet most rural domestic needs. Urbanization and the growing use of hired labour throughout the country created a demand for foodstuffs other than yams, cassava, plantains, and corn. An acquired taste for bread and beer led to significant imports of wheat.Cocoa beans became the main export crop, cultivated by more than one-quarter of the population, and by the late 1980s, after overtaking Ghana in cocoa bean exports, Côte d'Ivoire became the world's leading cocoa bean producer. Coffee, though it has fallen in export value, remains a favourite crop and business venture for many families in the southeast. Though the local coffee is of low quality, it constitutes a safe investment, and it enjoys a privileged position on the French market because of low production costs and much publicity. Thousands of acres close to the sea have been planted with coconut trees to increase the production of copra, the dried kernel from which coconut oil is extracted. The same area is also suitable for pineapples, a valuable export crop.

The southwest provides good soils and climate for oil palm and rubber trees. A South American species of hevea rubber tree was introduced in the early 1960s, and the cultivation of palm trees for oil was promoted at about the same time. In the north, cotton planting was fostered by using higher-yielding varieties; the practice of cotton-rice and cotton-yam crop rotation also increased yields.

The forest floor, after clearing, provides a rich soil for the cultivation of edible roots and bananas, as well as of such commercial tree crops as coffee, cacao (grown for its seeds, cocoa beans), and rubber. The savanna soils are good for rice and other cereals. Cotton and sugarcane grow in both areas.

Côte d'Ivoire was once primarily noted for its forest resources. About 30 species of trees are of high commercial value, the most important types being sipo (utile) and sambu (obeche). Forests underwent rapid depletion after many decades of exporting timber, exacerbated by overexploitation in the 1960s and '70s, and although reforestation was begun at numerous locations, illegal logging activity prevalent after the start of the civil war in 2002 and continuing in the following years contributed to the country's having one of the highest deforestation rates in the world.

Livestock raising prospers in the northeast, but national needs are also met by imports from Mali and Burkina Faso. Fishing, an important economic activity, is a traditional occupation in the lagoons and is also practiced on a commercial basis. Overfishing was a concern in the early 21st century.

Resources and power

Offshore reserves of petroleum and natural gas have been exploited since 1995 and are a significant source of export revenue for the country. Mineral resources exploited in Côte d'Ivoire include diamonds and gold. Deposits of iron ore, bauxite, and manganese also exist but have not been extensively developed, although iron ore is mined near Mount Nimba.

Almost three-quarters of the country's power is supplied by thermal stations, with hydroelectric sources supplying the remainder. Expansion of thermal capacity utilizing natural gas has been the focus of energy projects since the mid-1990s. Crude petroleum is refined in Abidjan to meet local needs, and refined products are exported to Mali, Burkina Faso, and other countries.

Manufacturing

The Ivoirian industrial sector retains much of the legacy of a colonial policy founded on export rather than the more desirable expansion of the local market. Many French and Lebanese companies shifted their headquarters to Abidjan after Dakar lost its status as the federal capital of the French West African federation when the regions in it became independent countries. More than 700 industrial companies were registered in the mid-1980s, but most of them were kept at low levels of activity, because of reluctance to invest capital locally and competition for skilled labourers. Nevertheless, the country became one of the best-equipped in western Africa. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the government has made a serious attempt to privatize many state-owned companies, including electricity and water utilities, as well as palm-oil and sugar companies.

Although the importance of petroleum-related industries increased in the early 21st century, Ivoirian industry rests largely on the agricultural sector—based on the development of timber, cotton, cacao, and coffee for export—that evolved during the period between the two World Wars. More crops were later added to these—among which pineapple became an outstanding success—as local canning and preserving facilities developed. Palm oil, also benefiting from equipment development, was used to produce fine soap and edible oils. Timber was used for furniture, cotton fabrics for garments, and sisal for string. Imported raw materials were shipped to local bakeries and breweries.

Finance

Côte d'Ivoire's monetary unit is the CFA (Communauté Financière Africaine) franc. From independence the CFA was pegged to the French franc; beginning in 2002, it was tied to the euro. The Central Bank of the States of West Africa (Banque Centrale des États de l'Afrique de l'Ouest) is the bank of issue for member states including Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo as well as Côte d'Ivoire. Many foreign and domestic banks, credit institutions, insurance companies, and real estate agencies exist in the country, most of which have headquarters in Abidjan. The city is also home to a regional stock exchange, Bourse Régionale des Valeurs Mobilières, that serves the French-speaking countries of western Africa.

Trade

Exports are reasonably diversified—though mostly agricultural and petroleum-related—with the United States and the countries of the European Union among the major destinations. Côte d'Ivoire primarily depends on France and Nigeria for imports, which include machinery and transport equipment, fuel, and food products.

Services

Until the 1970s, business travelers accounted for most of the visitors to the country. Since then tourism has expanded, although governmental upheavals have caused fluctuations.

Transportation and telecommunications

A single-track railway line connects Abidjan with Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso. The country's road network is one of the densest in sub-Saharan Africa. Paved roads have been extended to replace beaten-earth roads, and tolls were introduced on some roads in the mid-1990s. A secondary system of dry-season roads feeds the main roads. Daily local trade is still conducted along the innumerable tracks that crisscrossed the country long before the advent of Europeans.

As western Africa's largest container port, Abidjan has separate docking accommodations for passengers, for goods requiring special care such as bananas, minerals, and petroleum, for fishermen, and for boatmen who transport goods by canoe. Other ports are Sassandra, Tabou, and San-Pédro; the latter port largely handles timber and cocoa exports.

Abidjan has a fully equipped international airport, located at Port-Bouët. Other international airports exist at Bouaké and Yamoussoukro, and regional airports serve smaller areas. The national airline, Air Ivoire, serves the country's airports and landing fields in the interior, as well as some international destinations.

By regional standards, Côte d'Ivoire's telecommunications sector is fairly well-developed. In addition to telephone landline infrastructure, several mobile phone companies provide cellular service, which is growing in popularity. Internet service is available, although access is somewhat limited beyond urban areas.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

Côte d'Ivoire was proclaimed an independent republic on August 7, 1960. The 1960 constitution was suspended following the December 1999 military coup; under the new constitution approved in 2000, executive power is vested in the president, who serves a five-year term and can only be reelected once. The president appoints the prime minister and, with the prime minister's recommendations, the Council of Ministers. In addition, there are two other advisory bodies: the Economic and Social Council and the Constitutional Council. There is a single-house legislature, the National Assembly, with 225 members elected for five-year terms. Yamoussoukro was officially named the new national capital in 1983, but austerity measures and other factors have slowed the transfer of government functions, and Abidjan remains the de facto capital.

Local government

For administrative purposes, Côte d'Ivoire is divided into 19 régions, which are further divided into départements and communes, each with an elected council. Towns have elected municipal councils. In general, traditional authorities do not fit within such a regime, which is of French inspiration. Nevertheless, some chiefs, especially among the Akan group, have won elective positions.

Justice

Côte d'Ivoire has an independent judiciary. There are trial courts located in Abidjan, Bouaké, and Daloa, and their judges may be assigned to 25 other towns or be called upon to constitute special labour and juvenile courts. The same three towns are visited by an assize court dealing with serious criminal offenses. Abidjan also has a court of appeals and a supreme court.

Political process

The political system was controlled for 30 years by the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI), the only authorized party. It originated as a league of African farmers founded at the end of World War II by Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Houphouët-Boigny, Félix), who in 1960 would become the country's first president, a position he held until his death in 1993. In 1990 he was forced to accept the legalization of opposition parties and to allow contested presidential and legislative elections. Since then more than 100 political parties have been established.

Security

Côte d'Ivoire's military comprises an army, a navy, an air force, and a presidential guard. The army is by far the largest branch of the armed forces. Paramilitary forces include a presidential guard and gendarmerie.

Health and welfare

Health services in Côte d'Ivoire were comparatively good before the late 1980s, when the economic crisis made it hard to meet the needs of an exceptionally rapidly growing population. In 2002 the civil war severely disrupted health care services in the northern part of the country and caused many medical personnel to flee from the region; many have since returned and resumed practice. Western-style hospitals are located in Abidjan, Bouaké, Daloa, and Korhogo, and clinics can be found in other areas. There are many practitioners of indigenous forms of medicine, found throughout the country but especially in the rural areas. Since the late 1990s, AIDS has been an increasing problem; other significant health issues include tuberculosis and malaria.

Housing

Rural housing in Côte d'Ivoire varies among people and locations. Many houses in the southeastern quarter of the country are rectangular in shape and made of reeds, poles, or dried clay. Traditionally, roofs were thatched; corrugated iron sheets are now more frequently used. Houses among the Kru and other peoples of the southwestern forest zone may be either rectangular or round, varying according to place. Dwellings are clustered around a central open area, which often serves as an evening meeting place and is where councils of elders dispense justice. The Malinke of the northwestern part of the country build round houses of mud and sun-dried brick covered by a conical thatched roof. Fences surround the dwellings, which are clustered in compounds. In the northeastern corner of the country and as far away as northern Benin, distinctive rectangular houses that somewhat resemble castles are built out of mud or brick and are crowned with crenellated parapets built around a flat roof.

Education

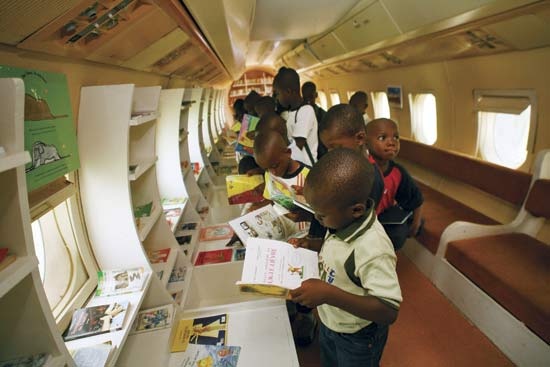

Educational services expanded considerably after independence, and primary education is both free of charge and officially compulsory for six years. Secondary schooling is provided in two cycles of three years and two years, respectively. The civil war that began in 2002 severely disrupted education in the country, particularly in the north, where the impact of both the war and subsequent administration by rebel forces lingered in the following years.

Educational services expanded considerably after independence, and primary education is both free of charge and officially compulsory for six years. Secondary schooling is provided in two cycles of three years and two years, respectively. The civil war that began in 2002 severely disrupted education in the country, particularly in the north, where the impact of both the war and subsequent administration by rebel forces lingered in the following years.Universities in Côte d'Ivoire include the University of Abobo-Adjamé and the University of Cocody, both in Abidjan, and the University of Bouaké; there are also several colleges in the country, primarily centred around Abidjan and Yamoussoukro.

The literacy rate of Côte d'Ivoire is slightly lower than the regional average and is significantly lower than the world average.

Cultural life

Cultural milieu

The cultural milieu has remained split, rather more completely than in other African countries, between a maze of ethnic-based cultures and a foreign intrusion that is almost exclusively French. Traditional arts flourish. The Senufo carve masks, decorate doors with esoteric symbols, and dance to the slow, majestic rhythms of drums supported by xylophones. The mountaineers of the Man forest wear masks showing horrifying faces, and they dance to a pace governed by the sound of drums and led by stilt-walkers. Versatile Baule artists make fine gold jewelry and wooden sculptures.

The cultural milieu has remained split, rather more completely than in other African countries, between a maze of ethnic-based cultures and a foreign intrusion that is almost exclusively French. Traditional arts flourish. The Senufo carve masks, decorate doors with esoteric symbols, and dance to the slow, majestic rhythms of drums supported by xylophones. The mountaineers of the Man forest wear masks showing horrifying faces, and they dance to a pace governed by the sound of drums and led by stilt-walkers. Versatile Baule artists make fine gold jewelry and wooden sculptures.The arts

Ivoirian literature in French was born in colonial times at the Ponty High School in Dakar, Senegal. One of its graduates, Bernard B. Dadié (Dadié, Bernard Binlin), became world-famous for autobiographical reminiscences in novel form. His schoolmates Coffi Gadeau and Amon d'Aby won a large local audience and many followers through their plays for the national theatre. A younger playwright, Zadi Zaourou, launched a chair in African literature at an Ivoirian university, and Ahmadou Kourouma (Kourouma, Ahmadou), a Muslim, inaugurated a new era of the Ivoirian novel with Les Soleils des indépendances (1968; “The Suns of Independence”), first published in Canada. Ake Loba is another well-known writer from the country.

Music is a vital part of Ivoirian culture. There is a strong tradition of griots who use music to help tell historical stories. The Senufo use marimbas and tuned iron gongs, among other instruments, to make their music. Music that combines both African and European traditions also exists. Alpha Blondy, who is strongly influenced by reggae, is Côte d'Ivoire's most internationally known musician.

Cultural institutions

The national library is located in Abidjan, as is a museum that houses a variety of artistic, ethnographic, and scientific collections. As the country's largest city, Abidjan also has an active nightlife and is known as the Paris of Africa. The Hotel Ivoire, which contains an ice-skating rink, a swimming pool, a bowling alley, a movie theatre, and other attractions, is located there. Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro Basilica (Yamoussoukro Basilica), which resembles St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, was built by former president Felix Houphouët-Boigny in Yamoussoukro, his hometown; upon completion in 1989, it was the largest Christian church in the world.

Sports and recreation

As in many other African countries, football (soccer) is a major sport in Côte d'Ivoire. A football field exists in just about every town and village, and there is at least one football club in every city. Côte d'Ivoire also has a baseball federation, and many Ivoirians play basketball and rugby. Tennis attracts a number of athletes, and the country has competed in the international Davis Cup tournament. The country made its Olympic (Olympic Games) debut at the 1964 Games in Tokyo, and it first entered the African Nations Cup (African Cup of Nations) in 1965. Gabriel Tiacoh was the first Ivoirian to win an Olympic medal when he won a silver medal in the men's 400-metre race at the 1984 Games held in Los Angeles.

Media and publishing

Although freedom of the press is guaranteed under the constitution, in reality it is restricted. Still, the press consists of many daily papers, weeklies, and periodicals, and this sector has become more lively since the 1990s. Almost all publications are published in French in Abidjan. Radio is the most prevalent media form throughout the country. Several radio stations exist, and they broadcast programs in French as well as in African languages. There is also a state-run television station; international television programming is available via satellite.

History

This article focuses on the history of Côte d'Ivoire from prehistoric and ancient times to the present. For more-detailed treatment of this country in its regional context, see Western Africa (western Africa, history of), history of.

Early history

Abundant archaeological evidence confirms the presence of early humans in what is now Côte d'Ivoire. Groups in the north were drawn into the trans-Saharan trade networks of the Ghana and Mali empires. Islam arrived with Malinke merchants as trade expanded. Mali's collapse in the 16th century resulted in a great upheaval that sent waves of migrants southward, where they founded new kingdoms in the hinterlands of the forest zone. The original inhabitants were either displaced or assimilated by these new groups.

Precolonial kingdoms

Important kingdoms flourished in the precolonial period. In the savanna country, towns developed around communities of Dyula traders. Kong existed for several centuries before Sekou Ouattara and his sons established a new dynasty there in the early 18th century. Kong lasted until 1897, when it was destroyed by Samory Touré (Samory), who was in the process of creating a new Muslim empire that included what is now northern Côte d'Ivoire. The Bouna kingdom was created in the late 17th century by Bounkani, an immigrant from Dagomba (now Ghana). It, along with Kong, became a major centre of Islamic learning.

The wars associated with the rise of the Asante empire in the late 17th century led to the migration of numerous Akan peoples into the forest region of Côte d'Ivoire. The most powerful of the states established was the Abron kingdom of Gyaman founded by Tan Daté. It was conquered by the Asante in the 1730s, and, despite numerous revolts, remained subject to it until 1875. In much the same circumstances the Anyi kingdoms of Indénié (Ndenye) and Sanwi were founded. Following the death in 1750 of the ruler of the Asante, Asantehene Opoku Ware, a succession struggle in Kumasi (the capital of the Asante empire) forced one contender, Queen Abla Poku (Awura Poku), and her supporters to enter the north-central part of Côte d'Ivoire. They founded the Baule kingdom, remarkable for its blending of Akan and local traditions.

Arrival of Europeans

Until the 19th century, European contact was confined to the coast, where French and Portuguese traders sought slaves and ivory. Louis-Édouard Bouet-Willaumez began signing treaties with coastal chiefs in the 1830s that allowed France to build forts and trading posts. France withdrew in 1870, but private merchants remained. Arthur Verdier sent explorers north and imported the first coffee plants. By the 1890s, inland penetration by traders such as Marcel Triech-Laplène and military missions such as those of Capt. Louis-Gustave Binger in 1887–89 resulted in more treaties and French “protectorate” relationships with many groups.

As the European rush to divide Africa accelerated, France claimed Côte d'Ivoire as a colony in 1893. Borders were determined in 1898, following the capture of Samory Touré. Gov. Gabriel Angoulvant began the military occupation in 1908. Imposition of forced labour and head taxes led to fierce resistance, especially among the Baule, Anyi, and Abe (Abbey). New revolts broke out when France conscripted thousands of Ivoirians to serve with other western African soldiers in World War I. France's superior weaponry eventually triumphed, although the colony was not considered under control until 1918.

March toward independence

Following World War I, concerted efforts toward economic development were taken. The railway was extended to Bobo Dioulasso, which, along with most of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), was attached to Côte d'Ivoire in 1933. Schools and Western-style health facilities were introduced, exploitation of the forests was intensified, and Africans were encouraged to plant cash crops for export. By 1939, Africans grew 90 percent of the cocoa and 80 percent of the coffee produced in the colony.

Forty thousand Ivoirians fought for the French army during World War II. Between 1940 and 1942 the colony, along with the rest of French West Africa, chose to remain under the Vichy government. Racist legislation, economic discrimination against African planters, increased forced labour, and a depression caused by Britain's naval blockade created enormous discontent. Educated Africans thus welcomed the subsequent Free French regime. In 1944 Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Houphouët-Boigny, Félix) and Auguste Denise formed the African Farmers Union (SAA), which, with the support of the colony's governor, André Latrille, secured equal treatment for African planters. Houphouët-Boigny's all-African slate swept local elections in 1945. The following year, with Côte d'Ivoire part of the French Union, he was elected to the French Assembly, where he spearheaded the law to abolish forced labour throughout the empire. The present borders were set in 1947, when the north reverted to the country of Upper Volta.

Côte d'Ivoire since independence

Houphouët-Boigny's rule

In 1946 Houphouët-Boigny helped found the African Democratic Rally (RDA), a western Africa–based umbrella organization that sought equality for Africans; the Ivoirian branch was the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI). Though at first harshly repressed, the RDA achieved many of its goals. In 1960 Houphouët-Boigny, who had been a cabinet minister in two French governments, was elected president of the newly independent Côte d'Ivoire. He ruled until his death, in 1993 during his seventh term in office. Despite reported coup attempts in 1963 and 1973, Houphouët-Boigny had a remarkable ability to reconcile opponents, which sustained the country's peaceful and prosperous relations with France and with its neighbours throughout most of his rule. However, political unrest and strained foreign relations were increasingly evident from the late 1980s. Côte d'Ivoire's first multiparty elections were held in 1990, and Houphouët-Boigny managed to defeat challenger Laurent Gbagbo (Gbagbo, Laurent) of the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) in a presidential election that was unsuccessfully appealed to the Supreme Court. Upon his death in 1993, Houphouët-Boigny was succeeded by the president of the National Assembly, Henri Konan Bédié, who was, like his predecessor, a member of the Baule ethnic group and the PDCI.

Political unrest

The PDCI and Bédié were victorious again in the1995 elections that were boycotted by most of the opposition. Long-standing ethnic and religious tensions continued to exist, exemplified by the government's attempt to rewrite the constitution to prevent certain challengers from running for president. With tensions escalating, soldiers mutinied on Dec. 23, 1999, and Brig. Gen. Robert Gueï, a former member of Houphouët-Boigny's government, took control of the country the next day. Although he pledged that he would allow legislative and presidential elections by October 2000 and that he would not be a candidate, he changed his mind and ran for president. After a controversial election in which Gueï tried to manipulate the outcome, Gbagbo of the FPI was eventually installed as president.

Civil war and its aftermath

Gbagbo's rule was not without discord, culminating in a failed coup on Sept. 19, 2002. Gueï, who the government claimed was behind the coup, was killed during the fighting. The failed coup fueled unrest and ignited civil war, leaving the country divided into the rebel-held north and the government-controlled south. Peacekeeping troops from France, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and later the United Nations (United Nations Peacekeeping Forces) (UN) created a buffer zone between the rebels and the Ivoirian government troops.

Although the government and rebel forces reached a peace agreement in January 2003, months of stalemate followed, and the cultural and nationalistic issues that had ignited the civil war—including land ownership, the basis for nationality, and qualifications for holding office—were never completely settled. Despite an initiative by UN and African leaders to restart the implementation of the peace agreement, simmering tensions exploded in November 2004 when the government violated the cease-fire agreement by bombing rebel-held areas in the north. The already volatile situation worsened when French peacekeeping troops were accidentally killed in one of the Ivoirian bombing raids, prompting retaliatory bombing by France that in turn resulted in anti-French demonstrations and the looting and burning of French businesses, schools, and residences. In response to the escalating situation, the UN Security Council (United Nations) imposed a 13-month arms embargo on Côte d'Ivoire in an attempt to stem the influx of weapons into the region. In April 2005, peace talks held in South Africa led to a new cease-fire agreement between the Ivoirian government and the rebels, with all parties declaring an end to the war. However, the terms of the agreement were not immediately implemented, and fighting resumed. In 2007, talks in Burkina Faso resulted in a power-sharing agreement signed by both sides, and a new transitional government was inaugurated that year.

Although the government and rebel forces reached a peace agreement in January 2003, months of stalemate followed, and the cultural and nationalistic issues that had ignited the civil war—including land ownership, the basis for nationality, and qualifications for holding office—were never completely settled. Despite an initiative by UN and African leaders to restart the implementation of the peace agreement, simmering tensions exploded in November 2004 when the government violated the cease-fire agreement by bombing rebel-held areas in the north. The already volatile situation worsened when French peacekeeping troops were accidentally killed in one of the Ivoirian bombing raids, prompting retaliatory bombing by France that in turn resulted in anti-French demonstrations and the looting and burning of French businesses, schools, and residences. In response to the escalating situation, the UN Security Council (United Nations) imposed a 13-month arms embargo on Côte d'Ivoire in an attempt to stem the influx of weapons into the region. In April 2005, peace talks held in South Africa led to a new cease-fire agreement between the Ivoirian government and the rebels, with all parties declaring an end to the war. However, the terms of the agreement were not immediately implemented, and fighting resumed. In 2007, talks in Burkina Faso resulted in a power-sharing agreement signed by both sides, and a new transitional government was inaugurated that year. Ed.

Additional Reading

International Business Publications USA, Côte d'Ivoire Country Study Guide (2007); Robert E. Handloff (ed.), Côte d'Ivoire: A Country Study (1991); Raymond Borremans, Le Grand Dictionnaire encyclopédique de la Côte d'Ivoire (1986–88); and Pierre Vennetier (ed.), Atlas de la Côte d'Ivoire, 2nd ed. rev. and updated by Pierre Vennetier and Geneviève Daverat (1983), provide a general overview of the country. Ethnographic studies include Enid Schildkrout (ed.), The Golden Stool: Studies of the Asante Center and Periphery (1987); and Ivor Wilks, Wa and the Wala (1989). An excellent memoir of life in a Senufo village is provided in Carol Spindel's In the Shadow of the Sacred Grove (1989).Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Profile: Côte d'Ivoire (annual), provides up-to-date information on the country's economy, resources, and industry. Laurent Gbagbo, La Côte-d'Ivoire (1982), is a critical history of economic and social developments in the 20 years before independence. Thomas J. Bassett, The Peasant Cotton Revolution in West Africa: Côte d'Ivoire, 1880–1995 (2001), discusses the growth of the cotton economy. Further discussions of economic history and policies are presented in Bastiaan A. Den Tuinder, Ivory Coast (1978); I. William Zartman and Christopher Delgado, The Political Economy of Ivory Coast (1984); Hartmut Schneider, Adjustment and Equity in Côte d'Ivoire; and John Rapley, Ivoirien Capitalism: African Entrepreneurs in Côte d'Ivoire (1993).Aristide R. Zolberg, One-Party Government in the Ivory Coast, rev. ed. (1969), is a landmark study of Ivoirian political history. A more contemporary view of politics is provided in Tessy D. Bakary Akin, La Démocratie par le haut en Côte-d'Ivoire (1992); and Francis Akindès, The Roots of the Military-Political Crises in Côte d'Ivoire (2004). Robert J. Mundt, Historical Dictionary of the Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire), 2nd ed. (1995), a valuable reference work, has an extensive bibliography. Jean-Noël Loucou, Histoire de la Côte d'Ivoire, vol. 1, La Formation des peuples (1984), presents the origin and development of the country's major ethnic groups. Timothy C. Weiskel, French Colonial Rule and the Baule Peoples: Resistance and Collaboration, 1889–1911 (1980), provides insight into the mindsets of those who imposed colonialism. F.J. Amon d'Aby, La Côte d'Ivoire dans la cité africaine (1951), is a pioneering and still valuable survey.

- Ingraham, Hubert

- Ingraj Bazar

- Ingram, John Kells

- Ingres, J.-A.-D

- ingress

- Ingrid Bergman

- Ingrid Betancourt

- Inguri Dam

- Ingushetia

- Inhambane

- inheritance

- inheritance tax

- inhibition

- Inigo Jones

- Inisa

- Initial Teaching Alphabet

- initiator

- injunction

- ink

- Inkatha Freedom Party

- inkblot test

- Ink Spots, the

- inkstand

- inky cap

- Inland Sea