Taft, William Howard

president and chief justice of United States

born September 15, 1857, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.

died March 8, 1930, Washington, D.C.

27th president of the United States (1909–13) and 10th chief justice of the United States (1921–30). As the choice of President Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Theodore) to succeed him and carry on the progressive Republican agenda, Taft as president alienated the progressives—and later Roosevelt—thereby contributing greatly to the split in Republican ranks in 1912, to the formation of the Bull Moose Party (also known as the Progressive Party), and to his humiliating defeat that year in his bid for a second term. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)

27th president of the United States (1909–13) and 10th chief justice of the United States (1921–30). As the choice of President Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Theodore) to succeed him and carry on the progressive Republican agenda, Taft as president alienated the progressives—and later Roosevelt—thereby contributing greatly to the split in Republican ranks in 1912, to the formation of the Bull Moose Party (also known as the Progressive Party), and to his humiliating defeat that year in his bid for a second term. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)The son of Alphonso Taft, secretary of war and attorney general (1876–77) under President Ulysses S. Grant (Grant, Ulysses S.), and Louisa Maria Torrey, Taft graduated second in his Yale class of 1878, studied law, and was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1880. Drawn to politics in the Republican Party, he served in several minor appointive offices until 1887, when he was named to fill the unfinished term of a judge of the superior court of Ohio. The following year he was elected to a five-year term of his own, the only time he ever attained office via popular vote other than his election to the presidency. From 1892 to 1900 he served as a judge of the United States Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, where he made several decisions hostile to organized labour. He upheld the use of an injunction to stop a strike by railroad workers, and he declared illegal the use of a secondary boycott. On the other hand, he upheld the rights of workers to organize, to join a union, and to strike, and he extended the power of the injunction to enforce antitrust laws.

Taft resigned his judgeship on March 15, 1900, to accept appointment by President William McKinley (McKinley, William) to serve as chairman of the Second Philippine Commission. Charged with organizing civil government in the islands following the Spanish-American War (1898), Taft displayed considerable talent as an executive and administrator. In 1901 he became the first civilian governor of the Philippines, concentrating in that post on the economic development of the islands. Fond of and very popular among the Philippine people, Taft twice refused to leave the islands when offered appointment to the Supreme Court by President Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Theodore). In 1904 he agreed to return to Washington to serve as Roosevelt's secretary of war, with the stipulation that he could continue to supervise Philippine affairs.

Taft resigned his judgeship on March 15, 1900, to accept appointment by President William McKinley (McKinley, William) to serve as chairman of the Second Philippine Commission. Charged with organizing civil government in the islands following the Spanish-American War (1898), Taft displayed considerable talent as an executive and administrator. In 1901 he became the first civilian governor of the Philippines, concentrating in that post on the economic development of the islands. Fond of and very popular among the Philippine people, Taft twice refused to leave the islands when offered appointment to the Supreme Court by President Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Theodore). In 1904 he agreed to return to Washington to serve as Roosevelt's secretary of war, with the stipulation that he could continue to supervise Philippine affairs.

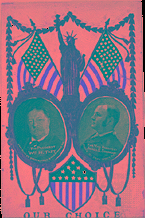

Cabinet of President William Howard TaftAlthough dissimilar in both physique and temperament, the rotund, easygoing Taft and the muscular, almost-manic Roosevelt nonetheless became close friends; the president regarded his secretary of war as a trusted adviser. When Roosevelt declined to run for reelection, he threw his support to Taft, who won the 1908 Republican nomination and defeated Democrat William Jennings Bryan (Bryan, William Jennings) in the electoral college by 321 votes to 162. Progressive Republicans, who had found their champion in Theodore Roosevelt, now expected Roosevelt's handpicked successor to carry forward their reform agenda. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address (William Howard Taft: Inaugural Address). See also Cabinet of President William Howard Taft.)

Cabinet of President William Howard TaftAlthough dissimilar in both physique and temperament, the rotund, easygoing Taft and the muscular, almost-manic Roosevelt nonetheless became close friends; the president regarded his secretary of war as a trusted adviser. When Roosevelt declined to run for reelection, he threw his support to Taft, who won the 1908 Republican nomination and defeated Democrat William Jennings Bryan (Bryan, William Jennings) in the electoral college by 321 votes to 162. Progressive Republicans, who had found their champion in Theodore Roosevelt, now expected Roosevelt's handpicked successor to carry forward their reform agenda. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address (William Howard Taft: Inaugural Address). See also Cabinet of President William Howard Taft.)However, progressives soon found abundant reason to be disappointed with Taft. Temperamentally, he lacked Roosevelt's compelling leadership qualities, which had inspired people to charge into battle against all that was wrong in American society. Politically, Taft offended progressives when he failed to appoint any from their ranks to his cabinet. He further angered progressives when he backed the Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909, a highly protectionist measure that ironically was the product of a special session of Congress called (by Taft) to revise tariff rates downward. Progressives, who favoured lower tariffs, expected a veto. When Taft not only signed the tariff but called it “the best bill that the party has ever passed,” the rupture in Republican ranks seemed unlikely to be mended. (See primary source document: Defense of a High Tariff. (William Howard Taft: Defense of a High Tariff))

Despite his close relationship with Roosevelt, Taft as president aligned himself with the more conservative members in the Republican Party. He did prove to be a vigorous trustbuster, however, launching twice as many antitrust prosecutions as had his progressive predecessor. He also backed conservation of natural resources, another key component of the progressive reform program. But when he fired Gifford Pinchot (Pinchot, Gifford)—head of the Bureau of Forestry, ardent conservationist, and close friend of Roosevelt—Taft severed whatever support he still had among Republican progressives.

Roosevelt returned from an African safari in 1910, and progressives quickly urged him to come out publicly in opposition to his political protégé. At first Roosevelt declined to criticize Taft by name, but by 1912 a breach between the former friends was clearly evident. When Roosevelt decided to challenge Taft for the Republican presidential nomination, the two attacked each other mercilessly in the Republican primary elections. The primary results proved beyond doubt that Republican voters wanted Roosevelt to be the party's standard-bearer in 1912, but Taft's forces controlled the convention and secured the nomination for the incumbent. Believing that the convention had been rigged and that their man had been cheated out of the nomination he deserved, Republican progressives bolted their party to form the Bull Moose (or Progressive) Party and nominated Roosevelt as their presidential candidate.

The split in Republican ranks assured the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson (Wilson, Woodrow). Roosevelt came in a distant second, and Taft, capturing less than a quarter of the popular vote, won just two states—Utah and Vermont. In the electoral college, Taft set a record for the poorest performance by an incumbent president seeking reelection: He won a mere 8 electoral votes compared with 88 for Roosevelt and 435 for Wilson.

The split in Republican ranks assured the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson (Wilson, Woodrow). Roosevelt came in a distant second, and Taft, capturing less than a quarter of the popular vote, won just two states—Utah and Vermont. In the electoral college, Taft set a record for the poorest performance by an incumbent president seeking reelection: He won a mere 8 electoral votes compared with 88 for Roosevelt and 435 for Wilson.As president, Taft frequently claimed that “politics makes me sick.” Never eager for the office, he had been prodded to pursue it by his wife, Helen Herron Taft (Taft, Helen), whom he had married in 1886. As first lady she was a key political adviser to her husband.

On his departure from the White House Taft returned to Yale, where he became a professor of constitutional law. With the entry of the United States into World War I, he served on the National War Labor Board, and at the war's conclusion he strongly supported American participation in the League of Nations (Nations, League of). In 1921 President Warren G. Harding (Harding, Warren G.) appointed Taft chief justice of the United States, launching what was probably the happiest period in Taft's long career in public service. He promptly took steps to improve the efficiency of the Supreme Court (Supreme Court of the United States), which had fallen far behind in its work. His influence was decisive in securing passage of the Judge's Act of 1925, which gave the Supreme Court greater discretion in choosing its cases so that it could focus more attention on constitutional questions and other issues of national importance.

On his departure from the White House Taft returned to Yale, where he became a professor of constitutional law. With the entry of the United States into World War I, he served on the National War Labor Board, and at the war's conclusion he strongly supported American participation in the League of Nations (Nations, League of). In 1921 President Warren G. Harding (Harding, Warren G.) appointed Taft chief justice of the United States, launching what was probably the happiest period in Taft's long career in public service. He promptly took steps to improve the efficiency of the Supreme Court (Supreme Court of the United States), which had fallen far behind in its work. His influence was decisive in securing passage of the Judge's Act of 1925, which gave the Supreme Court greater discretion in choosing its cases so that it could focus more attention on constitutional questions and other issues of national importance.Although generally conservative in his judicial philosophy, Taft was no rigid ideologue. His approval of court injunctions, for example, was limited by his insistence that injunctions could not be employed to interfere with the rights of workers to organize and strike. His most important contribution to constitutional law was his opinion in United States (Myers v. United States) (1926) upholding the authority of the president to remove federal officials, a much-belated endorsement of the position taken by Andrew Johnson (Johnson, Andrew) with respect to the Tenure of Office Act in his impeachment trial in 1868.

Suffering from heart disease, Taft resigned as chief justice on February 3, 1930, and he died a little more than a month later.

For additional writings by Taft, see Limited Presidential Power (William Howard Taft: Limited Presidential Power) and The Cabinet and the Congress (William Howard Taft: The Cabinet and the Congress).

Additional Reading

Biographies include Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard Taft, 2 vol. (1939, reissued 1986); and Bill Severn, William Howard Taft: The President Who Became Chief Justice (1970). Allen E. Ragan, Chief Justice Taft (1938); and Alpheus Thomas Mason, William Howard Taft, Chief Justice (1965, reprinted 1983), focus specifically on his Supreme Court years. Judith Icke Anderson, William Howard Taft (1981), a psychobiography, covers his life up to the conclusion of his term as president. Taft's administration is appraised in Paolo E. Coletta, The Presidency of William Howard Taft (1973). Donald F. Anderson, William Howard Taft: A Conservative's Conception of the Presidency (1973), analyzes Taft's theory and application of presidential power. David H. Burton, The Learned Presidency: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson (1988), advances the concept that the philosophies of these three presidents helped transform the passive presidencies of the 19th century into the dynamic presidencies of the 20th century. William Manners, TR and Will: A Friendship that Split the Republican Party (1969), focuses on the personal relationship between Taft and Theodore Roosevelt and emphasizes their arguments over public policy. Paolo E. Coletta, William Howard Taft: A Bibliography (1989), is a useful resource.

- John Drew, Jr.

- John Drew, Sr.

- John Drinkwater

- John D. Rockefeller

- John D. Rockefeller, III

- John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

- John Dryden

- John Dunmore Lang

- John Dunning, 1st Baron Ashburton

- John Dunning Ashburton, 1st Baron

- John Duns Scotus

- John Dunstable

- John Durang

- John Dury

- John Dwight

- John Dyer

- John Eales

- John Earle

- John Eaton, Jr.

- John E. Bruce: African American Plea for Organized Resistance to White Men (1889)

- John Edgar Wideman

- John Edwards

- John Elder

- John Eliot

- John Elliot Burns