Eisenhower, Dwight D.

president of United States

Introduction

in full Dwight David Eisenhower

born October 14, 1890, Denison, Texas, U.S.

died March 28, 1969, Washington, D.C.

34th president of the United States (1953–61), who had been supreme commander of the Allied forces in western Europe during World War II. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)

34th president of the United States (1953–61), who had been supreme commander of the Allied forces in western Europe during World War II. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)Early career

Eisenhower was the third of seven sons of David Jacob and Ida Elizabeth (Stover) Eisenhower. In the spring of 1891 the Eisenhowers left Denison, Texas, and returned to Abilene, Kansas, where their forebears had settled as part of a Mennonite colony. David worked in a creamery; the family was poor; and Dwight and his brothers were introduced to hard work and a strong religious tradition at an early age.

Eisenhower was the third of seven sons of David Jacob and Ida Elizabeth (Stover) Eisenhower. In the spring of 1891 the Eisenhowers left Denison, Texas, and returned to Abilene, Kansas, where their forebears had settled as part of a Mennonite colony. David worked in a creamery; the family was poor; and Dwight and his brothers were introduced to hard work and a strong religious tradition at an early age.

“Ike,” as Dwight was called, was a fun-loving youth who enjoyed sports but took only a moderate interest in his studies. The latter was perhaps a sign of one of his later characteristics: a dislike for the company of scholars. Dwight graduated from Abilene High School in 1909, worked for more than a year to support a brother's college education, and then entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, a decision that left his mother, a pacifist, in tears. He excelled in gridiron football but injured a knee in his second year at the academy and was forced to stop playing. In the remarkable class of 1915—which was to produce 59 generals—he ranked 61st academically and 125th in discipline out of the total of 164 graduates.

“Ike,” as Dwight was called, was a fun-loving youth who enjoyed sports but took only a moderate interest in his studies. The latter was perhaps a sign of one of his later characteristics: a dislike for the company of scholars. Dwight graduated from Abilene High School in 1909, worked for more than a year to support a brother's college education, and then entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, a decision that left his mother, a pacifist, in tears. He excelled in gridiron football but injured a knee in his second year at the academy and was forced to stop playing. In the remarkable class of 1915—which was to produce 59 generals—he ranked 61st academically and 125th in discipline out of the total of 164 graduates. Commissioned a second lieutenant, he was sent to San Antonio, Texas, where he met Mamie Geneva Doud (Mamie Eisenhower (Eisenhower, Mamie)), daughter of a successful Denver, Colorado, meat packer. They were married in 1916 and had two sons: Doud Dwight, born in 1917, who died of scarlet fever in 1921, and John Sheldon Doud, born in 1922.

Commissioned a second lieutenant, he was sent to San Antonio, Texas, where he met Mamie Geneva Doud (Mamie Eisenhower (Eisenhower, Mamie)), daughter of a successful Denver, Colorado, meat packer. They were married in 1916 and had two sons: Doud Dwight, born in 1917, who died of scarlet fever in 1921, and John Sheldon Doud, born in 1922. During World War I, Eisenhower commanded a tank training centre, was promoted to captain, and received the Distinguished Service Medal. The war ended just before he was to be sent overseas. From 1922 to 1924 he was assigned to the Panama Canal Zone, and there he came under the inspiring influence of his commander, Brigadier General Fox Conner. With Conner's assistance, Eisenhower was selected to attend the army's Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Then a major, he graduated first in a class of 275 in 1926 and two years later graduated from the Army War College. He then served in France (where he wrote a guidebook of World War I battlefields) and in Washington, D.C., before becoming an aide to Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur (MacArthur, Douglas) in 1933. Two years later he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines to assist in the reorganization of the commonwealth's army, and while there he was awarded the Distinguished Service Star of the Philippines and promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He returned to the United States shortly after Germany's invasion of Poland initiated the European phase of World War II, and in March 1941 he became a full colonel. Three months later he was made chief of staff of the Third Army, and he soon won the attention of Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall (Marshall, George Catlett) for his role in planning war games involving almost 500,000 troops.

During World War I, Eisenhower commanded a tank training centre, was promoted to captain, and received the Distinguished Service Medal. The war ended just before he was to be sent overseas. From 1922 to 1924 he was assigned to the Panama Canal Zone, and there he came under the inspiring influence of his commander, Brigadier General Fox Conner. With Conner's assistance, Eisenhower was selected to attend the army's Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Then a major, he graduated first in a class of 275 in 1926 and two years later graduated from the Army War College. He then served in France (where he wrote a guidebook of World War I battlefields) and in Washington, D.C., before becoming an aide to Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur (MacArthur, Douglas) in 1933. Two years later he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines to assist in the reorganization of the commonwealth's army, and while there he was awarded the Distinguished Service Star of the Philippines and promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He returned to the United States shortly after Germany's invasion of Poland initiated the European phase of World War II, and in March 1941 he became a full colonel. Three months later he was made chief of staff of the Third Army, and he soon won the attention of Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall (Marshall, George Catlett) for his role in planning war games involving almost 500,000 troops.Supreme commander

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Marshall appointed Eisenhower to the army's war plans division in Washington, D.C., where he prepared strategy for an Allied invasion of Europe. Eisenhower had been made a brigadier general in September 1941 and was promoted to major general in March 1942; he was also named head of the operations division of the War Department. In June Marshall selected him over 366 senior officers to be commander of U.S. troops in Europe. Eisenhower's rapid advancement, after a long army career spent in relative obscurity, was due not only to his knowledge of military strategy and talent for organization but also to his ability to persuade, mediate, and get along with others. Men from a wide variety of backgrounds, impressed by his friendliness, humility, and persistent optimism, liked and trusted him. A phrase that later became one of the most famous campaign slogans in American history seemed to reflect the impression of everyone who met him: “I like Ike!”

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Marshall appointed Eisenhower to the army's war plans division in Washington, D.C., where he prepared strategy for an Allied invasion of Europe. Eisenhower had been made a brigadier general in September 1941 and was promoted to major general in March 1942; he was also named head of the operations division of the War Department. In June Marshall selected him over 366 senior officers to be commander of U.S. troops in Europe. Eisenhower's rapid advancement, after a long army career spent in relative obscurity, was due not only to his knowledge of military strategy and talent for organization but also to his ability to persuade, mediate, and get along with others. Men from a wide variety of backgrounds, impressed by his friendliness, humility, and persistent optimism, liked and trusted him. A phrase that later became one of the most famous campaign slogans in American history seemed to reflect the impression of everyone who met him: “I like Ike!”Eisenhower was promoted to lieutenant general in July 1942 and named to head Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa. This first major Allied offensive of the war was launched on November 8, 1942, and successfully completed in May 1943. Eisenhower's decision to work during the campaign with the French admiral François Darlan (Darlan, François), who had collaborated with the Germans, aroused a storm of protest from the Allies, but his action was defended by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Franklin D.). A full general since that February, Eisenhower then directed the amphibious assault of Sicily and the Italian mainland, which resulted in the fall of Rome on June 4, 1944.

During the fighting in Italy, Eisenhower participated in plans to cross the English Channel for an invasion of France. On December 24, 1943, he was appointed supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, and the next month he was in London making preparations for the massive thrust into Europe. On June 6, 1944, he gambled on a break in bad weather and gave the order to launch the Normandy Invasion, the largest amphibious attack in history. On D-Day more than 156,000 troops landed in Normandy. Invading Allied forces eventually numbered 1,000,000 and began to fight their way into the heart of France. On August 25 Paris was liberated. After winning the Battle of the Bulge (Bulge, Battle of the)—a fierce German counterattack in the Ardennes in December—the Allies crossed the Rhine on March 7, 1945. Germany surrendered on May 7, ending the war in Europe. Although Eisenhower was criticized, then and later, for allowing the Russians to capture the enemy capital of Berlin, he and others defended his actions on several grounds (the Russians were closer, had more troops, and had been promised Berlin at the Yalta Conference of February 1945). In the meantime, in December 1944, Eisenhower had been made a five-star general.

During the fighting in Italy, Eisenhower participated in plans to cross the English Channel for an invasion of France. On December 24, 1943, he was appointed supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, and the next month he was in London making preparations for the massive thrust into Europe. On June 6, 1944, he gambled on a break in bad weather and gave the order to launch the Normandy Invasion, the largest amphibious attack in history. On D-Day more than 156,000 troops landed in Normandy. Invading Allied forces eventually numbered 1,000,000 and began to fight their way into the heart of France. On August 25 Paris was liberated. After winning the Battle of the Bulge (Bulge, Battle of the)—a fierce German counterattack in the Ardennes in December—the Allies crossed the Rhine on March 7, 1945. Germany surrendered on May 7, ending the war in Europe. Although Eisenhower was criticized, then and later, for allowing the Russians to capture the enemy capital of Berlin, he and others defended his actions on several grounds (the Russians were closer, had more troops, and had been promised Berlin at the Yalta Conference of February 1945). In the meantime, in December 1944, Eisenhower had been made a five-star general. Eisenhower was given a hero's welcome upon returning to the United States for a visit in June 1945, but in November his intended retirement was delayed when President Harry S. Truman (Truman, Harry S.) named him to replace Marshall as chief of staff. For more than two years Eisenhower directed demobilization of the wartime army and worked to unify the armed services under a centralized command. In May 1948 he left active duty the most popular and respected soldier in the United States and became president of Columbia University in New York City. His book Crusade in Europe, published that fall, made him a wealthy man.

Eisenhower was given a hero's welcome upon returning to the United States for a visit in June 1945, but in November his intended retirement was delayed when President Harry S. Truman (Truman, Harry S.) named him to replace Marshall as chief of staff. For more than two years Eisenhower directed demobilization of the wartime army and worked to unify the armed services under a centralized command. In May 1948 he left active duty the most popular and respected soldier in the United States and became president of Columbia University in New York City. His book Crusade in Europe, published that fall, made him a wealthy man. Eisenhower's brief career as an academic administrator was not especially successful. His technical education and military experience prepared him poorly for the post. In the fall of 1950 President Truman asked him to become supreme commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and in early 1951 he flew to Paris to assume his new position. For the next 15 months he devoted himself to the task of creating a united military organization in western Europe to be a defense against the possibility of communist aggression.

Eisenhower's brief career as an academic administrator was not especially successful. His technical education and military experience prepared him poorly for the post. In the fall of 1950 President Truman asked him to become supreme commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and in early 1951 he flew to Paris to assume his new position. For the next 15 months he devoted himself to the task of creating a united military organization in western Europe to be a defense against the possibility of communist aggression.First term as president

As early as 1943 Eisenhower was mentioned as a possible presidential candidate. His personal qualities and military reputation prompted both parties to woo him. As the campaign of 1952 neared, Eisenhower let it be known that he was a Republican, and the eastern wing of the party, headed by Governor Thomas E. Dewey (Dewey, Thomas E.) of New York, made an intensive effort to persuade him to seek the Republican presidential nomination. His name was entered in several state primaries against the more conservative Senator Robert A. Taft (Taft, Robert A.) of Ohio. Although the results were mixed, Eisenhower decided to run. In June 1952 he retired from the army after 37 years of service, returned to the United States, and began to campaign actively. At the party convention in July, after a bitter fight with Taft supporters, Eisenhower won the nomination on the first ballot. His running mate was Senator Richard M. Nixon (Nixon, Richard M.) of California. The Democrats nominated Governor Adlai E. Stevenson (Stevenson, Adlai E) of Illinois for president and Senator John Sparkman of Alabama for vice president.

As early as 1943 Eisenhower was mentioned as a possible presidential candidate. His personal qualities and military reputation prompted both parties to woo him. As the campaign of 1952 neared, Eisenhower let it be known that he was a Republican, and the eastern wing of the party, headed by Governor Thomas E. Dewey (Dewey, Thomas E.) of New York, made an intensive effort to persuade him to seek the Republican presidential nomination. His name was entered in several state primaries against the more conservative Senator Robert A. Taft (Taft, Robert A.) of Ohio. Although the results were mixed, Eisenhower decided to run. In June 1952 he retired from the army after 37 years of service, returned to the United States, and began to campaign actively. At the party convention in July, after a bitter fight with Taft supporters, Eisenhower won the nomination on the first ballot. His running mate was Senator Richard M. Nixon (Nixon, Richard M.) of California. The Democrats nominated Governor Adlai E. Stevenson (Stevenson, Adlai E) of Illinois for president and Senator John Sparkman of Alabama for vice president. Despite his age (61), Eisenhower campaigned tirelessly, impressing millions with his warmth and sincerity. His wide, friendly grin, wartime heroics, and middle-class pastimes—he was an avid golfer and bridge player and a fan not of highbrow literature but of the American western—endeared him to the public and garnered him vast support. Like her husband, Mamie Eisenhower projected a down-to-earth image. She remained an ardent supporter of him, though their marriage had been strained by rumours of an affair during World War II between Eisenhower and his driver-secretary Kay Summersby.

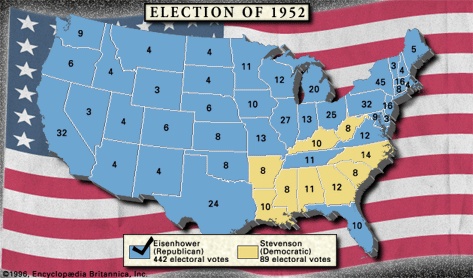

Despite his age (61), Eisenhower campaigned tirelessly, impressing millions with his warmth and sincerity. His wide, friendly grin, wartime heroics, and middle-class pastimes—he was an avid golfer and bridge player and a fan not of highbrow literature but of the American western—endeared him to the public and garnered him vast support. Like her husband, Mamie Eisenhower projected a down-to-earth image. She remained an ardent supporter of him, though their marriage had been strained by rumours of an affair during World War II between Eisenhower and his driver-secretary Kay Summersby. Eisenhower urged economy and honesty in government and promised to visit Korea to explore the possibilities for ending the Korean War, which had broken out in 1950 between communist North Korea and pro-Western South Korea and soon involved United Nations (mainly U.S.) troops and communist Chinese forces. Many Republicans, including Nixon, spoke of pro-communist disloyalty within the Truman administration and called for stringent antisubversive measures. The Eisenhower-Nixon ticket won handily, carrying 39 states, winning the electoral vote 442 to 89, and collecting more than 33 million popular votes. (See primary source document: First Inaugural Address (Dwight D. Eisenhower: First Inaugural Address).) The Republican Party won control of Congress by a slim margin but lost both houses two years later.

Eisenhower urged economy and honesty in government and promised to visit Korea to explore the possibilities for ending the Korean War, which had broken out in 1950 between communist North Korea and pro-Western South Korea and soon involved United Nations (mainly U.S.) troops and communist Chinese forces. Many Republicans, including Nixon, spoke of pro-communist disloyalty within the Truman administration and called for stringent antisubversive measures. The Eisenhower-Nixon ticket won handily, carrying 39 states, winning the electoral vote 442 to 89, and collecting more than 33 million popular votes. (See primary source document: First Inaugural Address (Dwight D. Eisenhower: First Inaugural Address).) The Republican Party won control of Congress by a slim margin but lost both houses two years later.Eisenhower's basically conservative views on domestic affairs were shared by his secretary of the treasury, George M. Humphrey. The administration's domestic program, which came to be labeled “modern Republicanism,” called for reduced taxes, balanced budgets, a decrease in government control over the economy, and the return of certain federal responsibilities to the states. Controls over rents, wages, and prices were allowed to expire, and in 1954 there was a slight tax revision. At Eisenhower's insistence Congress transferred the title to valuable tideland oil reserves to the states. But there was no sharp break with policies inherited from previous Democratic administrations. The needs of an expanding population (which grew from 155 million to 179 million during the Eisenhower era) and the country's overseas commitments caused budget deficits during five out of eight years. The minimum wage was increased to $1 per hour; the Social Security System was broadened; and in the spring of 1953 the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare was created.

The right wing of the Republican Party clashed with the president more often than the Democrats did during his first term. For example, Eisenhower expended a great deal of time and energy defeating the Bricker Amendment of 1954, the bill sponsored by Republican Senator John Bricker of Ohio that would have limited the president's liberty to negotiate international treaties that violated the rights of U.S. states. The bill fell only one vote short; it was a victory for the president's extensive lobbying campaign. But by far the largest challenge came from Senator Joseph R. McCarthy (McCarthy, Joseph R.) of Wisconsin. In part to preserve party unity, Eisenhower had refused to publicly condemn Senator McCarthy's charges of communist (communism) influence within the government. Although privately Eisenhower expressed his distaste for the senator, at times he seemed to encourage the attacks of McCarthyites. Hundreds of federal employees were fired under his expanded loyalty-security program. With his approval Congress passed a law designed to outlaw the American Communist Party. Following the sensational hearings on McCarthy's charges against army and civilian officials, televised nationally for five weeks in the spring of 1954, McCarthy's popularity waned, as did the anticommunist hysteria.

Foreign affairs drew much of Eisenhower's attention. He and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles (Dulles, John Foster), worked hard at achieving peace by constructing collective defense agreements and by threatening the Soviet Union with “massive retaliatory power”; both strategies were designed to check the spread of communism. Another strategy was unknown to the public at the time but was heavily criticized in later years: the use of the Central Intelligence Agency in covert operations to overthrow governments in Iran (1953) and Guatemala (1954).

Eisenhower kept his campaign promise and visited Korea shortly after his inauguration. Partly, perhaps, because of Joseph Stalin's death in March 1953 and partly because Eisenhower hinted at his willingness to use nuclear weapons, the president was able to negotiate a truce for the Korean War in July 1953. In December of that year he proposed to the United Nations that the countries of the world pool atomic information and materials under the auspices of an international agency. This Atoms for Peace speech (see original text (Dwight D. Eisenhower: Atoms for Peace)) bore fruit in 1957, when 62 countries formed the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Eisenhower kept his campaign promise and visited Korea shortly after his inauguration. Partly, perhaps, because of Joseph Stalin's death in March 1953 and partly because Eisenhower hinted at his willingness to use nuclear weapons, the president was able to negotiate a truce for the Korean War in July 1953. In December of that year he proposed to the United Nations that the countries of the world pool atomic information and materials under the auspices of an international agency. This Atoms for Peace speech (see original text (Dwight D. Eisenhower: Atoms for Peace)) bore fruit in 1957, when 62 countries formed the International Atomic Energy Agency.In July 1955 the president met with leaders of Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union at a summit conference in Geneva. His “open skies” proposal, by which the United States and the Soviet Union would permit continuous air inspection of each other's military installations, was welcomed by world opinion but was rejected by the U.S.S.R. In September 1954 Eisenhower and Dulles succeeded in creating the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) to prevent further communist expansion. It was composed of the United States, France, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan. NATO was strengthened in 1955 by the inclusion of West Germany.

Critics contended that there were frequent disparities between the administration's words and its deeds in the field of foreign relations. While threatening to “unleash” Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, the United States signed a defense treaty with Nationalist China in December 1954 that inhibited Chiang's ability to attack the communist Chinese. Moreover, Dulles spoke of “liberating” captive peoples in communist countries, but the administration stopped short of this and limited itself to protests when uprisings occurred in East Germany (1953) and Hungary (1956). While the secretary of state promised “massive retaliation” against communist aggression, the president made the decision to limit the American role in the Indochina crisis between France and the guerrillas led by Ho Chi Minh to pushing for a partition of Vietnam into a communist North and a noncommunist South and to providing financial and military aid to the latter.

Second term

A heart attack in September 1955 and an operation for ileitis in June 1956 raised considerable doubt about Eisenhower's ability to serve a second term. But he recovered quickly, and the Republican convention unanimously endorsed the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket on the first ballot. The Democrats again selected Adlai E. Stevenson and named Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee as his running mate, but Eisenhower's great personal popularity turned the election into a landslide victory, the most one-sided race since 1936, as the Republican ticket garnered more than 57 percent of the popular vote and won the electoral vote 457 to 73. (See primary source document: Second Inaugural Address (Dwight D. Eisenhower: Second Inaugural Address).) Nevertheless, the Democrats once more captured both houses of Congress, a feat they were to duplicate in 1958. Eisenhower was the first president to serve with three Congresses controlled by the opposition party.

A heart attack in September 1955 and an operation for ileitis in June 1956 raised considerable doubt about Eisenhower's ability to serve a second term. But he recovered quickly, and the Republican convention unanimously endorsed the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket on the first ballot. The Democrats again selected Adlai E. Stevenson and named Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee as his running mate, but Eisenhower's great personal popularity turned the election into a landslide victory, the most one-sided race since 1936, as the Republican ticket garnered more than 57 percent of the popular vote and won the electoral vote 457 to 73. (See primary source document: Second Inaugural Address (Dwight D. Eisenhower: Second Inaugural Address).) Nevertheless, the Democrats once more captured both houses of Congress, a feat they were to duplicate in 1958. Eisenhower was the first president to serve with three Congresses controlled by the opposition party. The election campaign of 1956, however, had been complicated by a crisis in the Middle East over Egypt's seizure of the Suez Canal (Suez Crisis). The subsequent attack on Egypt by Great Britain, France, and Israel and the Soviet Union's support of Egypt prompted the president to go before Congress in January 1957 to urge adoption of what came to be called the Eisenhower Doctrine, a pledge to send U.S. armed forces to any Middle Eastern country requesting assistance against communist aggression.

The election campaign of 1956, however, had been complicated by a crisis in the Middle East over Egypt's seizure of the Suez Canal (Suez Crisis). The subsequent attack on Egypt by Great Britain, France, and Israel and the Soviet Union's support of Egypt prompted the president to go before Congress in January 1957 to urge adoption of what came to be called the Eisenhower Doctrine, a pledge to send U.S. armed forces to any Middle Eastern country requesting assistance against communist aggression.When the U.S. Supreme Court, on May 17, 1954, declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional (Board of Education of Topeka (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka)), controversy and violence broke out, especially in the South. In September 1957 Eisenhower dispatched 1,000 federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to halt an attempt by Governor Orval E. Faubus to obstruct a federal court order integrating a high school. This action was the most serious challenge of his presidency. On several occasions Eisenhower had expressed distaste for racial segregation, though he doubtless believed that the process of integration would take time. Significantly, the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first such law passed since 1875.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the first man-made satellite to orbit the Earth. Americans were stunned by the achievement, and many blamed Eisenhower for the administration's insistence on low military budgets and its failure to develop a space program. Steps were taken to boost space research and to provide funds to increase the study of science, and these culminated in the creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in July 1958. The administration again came under fire in the fall of 1957 for an economic recession that lasted through the following summer. For fear of fueling inflation, Eisenhower refused to lower taxes or increase federal spending to ease the slump.

Following the death of Dulles in the spring of 1959, Eisenhower assumed a more vigorous and personal role in the direction of American foreign policy. He traveled over 300,000 miles (480,000 km) to some 27 countries in his last two years of office, a period historians have termed the era of “the new Eisenhower.” His masterly use of the new medium of television—holding regularly televised news conferences and participating in high-profile motorcades in foreign capitals around the world—and his exploitation of the advent of jet travel captivated the public and led some scholars to term Eisenhower the first of the imperial presidents. To improve relations with the Soviet Union, he invited Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev (Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeyevich) to visit the United States. Khrushchev toured parts of the country in September 1959 and held private talks with Eisenhower. Another summit meeting was planned, and a new era of personal diplomacy seemed at hand. But when a U-2 (U-2 Affair) reconnaissance plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers (Powers, Francis Gary) of the United States was shot down over the U.S.S.R. in May 1960, Khrushchev scuttled the talks and angrily withdrew his invitation to Eisenhower to visit the Soviet Union. Eisenhower admitted that the flights had gone on for four years and shouldered much of the blame for the ill-timed affair. In January 1961, during the last weeks of the Eisenhower administration, the United States broke diplomatic relations with Cuba, which for two years had been under the control of Fidel Castro (Castro, Fidel).

Although his administrations had a great many critics, Eisenhower remained extraordinarily popular. In his Farewell Address (see original text (Dwight D. Eisenhower: Farewell Address)) he warned against the rise and power of “the military-industrial complex,” but his successors ignored him amid the perceived demands of the Cold War. When he left office, Congress restored his rank as general of the army. He retired to his farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and devoted much of his time to his memoirs. In 1963 he published Mandate for Change, which was followed in 1965 by Waging Peace. A lighter work, At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends, appeared in 1967.

Although his administrations had a great many critics, Eisenhower remained extraordinarily popular. In his Farewell Address (see original text (Dwight D. Eisenhower: Farewell Address)) he warned against the rise and power of “the military-industrial complex,” but his successors ignored him amid the perceived demands of the Cold War. When he left office, Congress restored his rank as general of the army. He retired to his farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and devoted much of his time to his memoirs. In 1963 he published Mandate for Change, which was followed in 1965 by Waging Peace. A lighter work, At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends, appeared in 1967.Cabinet of President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Cabinet of President Dwight D. Eisenhower Cabinet of President Dwight D. EisenhowerThe table provides a list of cabinet members in the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Additional Reading

Dwight D. Eisenhower's papers are collected in Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., and Louis Galambos (eds.), The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower (1970– ).Eisenhower's entire career is presented in Marquis William Childs, Eisenhower: Captive Hero (1958), a convincing interpretation; Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower, 2 vol. (1983–84); Robert F. Burk, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Hero and Politician (1986); and Michael R. Beschloss and Vincent Virga, Eisenhower: A Centennial Life (1990), which is extensively illustrated. Treatments of Eisenhower during World War II include Stephen E. Ambrose, The Supreme Commander (1970); David Eisenhower, Eisenhower at War, 1943–1945 (1986– ), by his grandson; and Norman Gelb, Ike and Monty: Generals at War (1994), which deals with Eisenhower as the supreme Allied commander and Bernard Law Montgomery, the British commander.Eisenhower's presidency is examined in Emmet John Hughes, The Ordeal of Power (1963, reissued 1975), a brilliant critique of the first term; Dean Albertson (ed.), Eisenhower as President (1963), containing first-rate assessments; Herbert S. Parmet, Eisenhower and the American Crusades (1972); Charles C. Alexander, Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952–1961 (1975); William Bragg Ewald, Jr., Eisenhower the President: Crucial Days, 1951–1960 (1981), written by a White House staff member during Eisenhower's presidency; Fred I. Greenstein, The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader (1982, reissued 1994), which argues that Eisenhower was a politically strong leader, not weak as thought by many; and Chester J. Pach, Jr., and Elmo Richardson, The Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (rev. ed., 1991).Works dealing with foreign relations during Eisenhower's presidency include John P. Burke, et al. , How Presidents Test Reality: Decisions on Vietnam, 1954 and 1965 (1989), which analyzes Eisenhower's nonintervention at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 in comparison with Lyndon B. Johnson's 1965 intervention; David W. Lesch, Syria and the United States: Eisenhower's Cold War in the Middle East (1992); and Isaac Alteras, Eisenhower and Israel: U.S.-Israeli Relations, 1953–1960 (1993). Jeff Broadwater, Eisenhower & the Anti-Communist Crusade (1992), examines Eisenhower's handling of the U.S. communist issue, from the beginning of the Cold War through his presidency. Eisenhower's reaction to the 1957 Soviet launch of the first artificial Earth satellite is assessed in Robert A. Divine, The Sputnik Challenge (1993). Craig Allen, Eisenhower and the Mass Media: Peace, Prosperity & Prime-Time TV (1993), discusses Eisenhower's use of television to shape public opinion throughout his presidency. Günter Bischof and Stephen E. Ambrose (eds.), Eisenhower: A Centenary Assessment (1995), collects essays by revisionist and postrevisionist scholars.Biographical studies of Eisenhower's wife, Mamie Doud Eisenhower, include Dorothy Brandon, Mamie Doud Eisenhower: A Portrait of a First Lady (1954); Alden Hatch, Red Carpet for Mamie (1954); and Lester David and Irene David, Ike and Mamie: The Story of the General and His Lady (1981). Ed.

- Fidel Ramos

- Fidenza

- Fides

- Fidesz

- fiduciary

- Fiedler, Arthur

- Fiedler, Leslie A.

- fief

- field archery

- field artillery

- Field axioms

- Field, Cyrus W

- Field, David Dudley

- field emission

- Fielden, John

- Field, Eugene

- field hockey

- Fielding, Henry

- Fielding, Sarah

- Fielding, Sir John

- Fielding, William Stevens

- Fielding Yost

- Field, John

- Field, Marshall

- Field Museum of Natural History