advanced structural ceramics

Introduction

ceramic materials that demonstrate enhanced mechanical properties under demanding conditions. Because they serve as structural members, often being subjected to mechanical loading, they are given the name structural ceramics. Ordinarily, for structural applications ceramics tend to be expensive replacements for other materials, such as metals, polymers, and composites. For especially erosive, corrosive, or high-temperature environments, however, they may be the material of choice. This is because the strong chemical bonding in ceramics—described in the article ceramic composition and properties: Chemical bonds (ceramic composition and properties)—makes them exceptionally robust in demanding situations. For example, some advanced ceramics display superior wear resistance, making them ideal for tribological (wear) applications such as mineral processing equipment. Others are chemically inert and therefore are used as bone replacements in the highly corrosive environment of the human body. High bond strengths also make ceramics thermochemically inert; this property shows promising areas of application in engines for automobiles, aerospace vehicles, and power generators.

A number of technological barriers have to be surmounted in order to make advanced structural ceramics an everyday reality. The most significant challenges are the inherent flaw sensitivity, or brittleness, of ceramics and the variability of their mechanical properties. In this article toughening methods are described and prospects for toughened ceramics assessed. The survey ends with links to articles on various established and prospective applications for advanced structural ceramics.

Toughening methods

Reinforced ceramics

Among the strategies for achieving ceramics with improved mechanical properties, especially toughness, some involve the engineering of microstructures that either resist the propagation of cracks or absorb energy during the crack propagation process. Both goals can be achieved simultaneously in microstructures with fibrous or interlocked grains. In ceramics produced with such microstructures, cracks are deflected from a straight path, leading to a dramatic increase in crack length; at the same time particles behind the advancing crack tip bridge the crack, tending to hold it closed. Crack deflection and crack bridging also occur in whisker-reinforced and fibre-reinforced ceramic composites. The result is increased fracture surface area and much greater energy absorption.

Microcracking

Another mechanism that can lead to increased fracture toughness in ceramics is microcracking, which occurs in single-phase polycrystalline ceramics whose grains are anisotropic (that is, whose mechanical properties vary with direction) or in intentionally biphasic polycrystalline microstructures. In these materials tiny microcracks open up to either side of the main crack path ahead of the advancing crack tip. This phenomenon has two effects. First, the energy that goes into the opening of the subsidiary cracks increases the energy needed for propagation of the main crack. Second, as the main crack propagates, microcracks opening up in the wake or process zone adjacent to the main crack but behind the crack front result in an increase in volume, which tends to close the main crack. The resistance to propagation thus increases the farther the crack propagates.

Transformation toughening

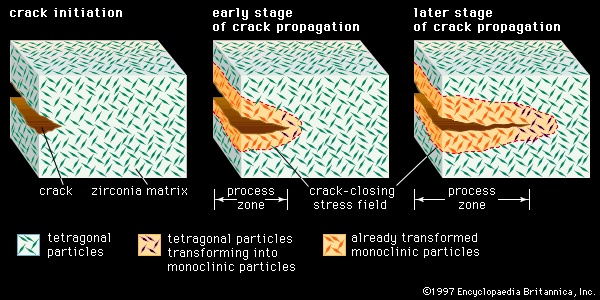

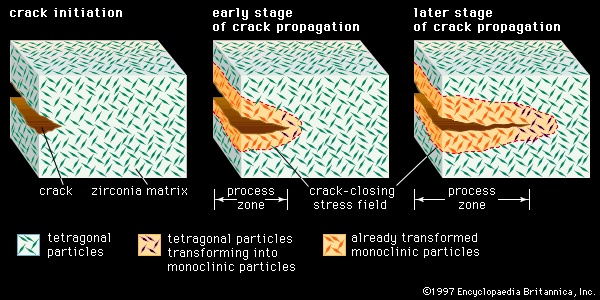

The most promising toughening mechanism for ceramic materials involves a phase transformation; the method is referred to as transformation toughening and is illustrated in Figure 1-->

The most promising toughening mechanism for ceramic materials involves a phase transformation; the method is referred to as transformation toughening and is illustrated in Figure 1--> . Although other materials such as alumina can be transformation-toughened, zirconia (zirconium dioxide, ZrO2) is the prototype material for this process. Pure zirconia, upon cooling below 1,150° C (2,100° F), undergoes a dramatic 3 percent volume expansion as it transforms from a tetragonal form to a monoclinic form. This expansion can be used to advantage by dispersing extremely fine tetragonal particles in a matrix of cubic zirconia or alumina. The small size of the particles (less than 1 micrometre) and their intimate contact with the matrix induce the tetragonal structure to remain stable at room temperature. Ahead of an advancing crack, however, a stress field triggers the transformation of the embedded tetragonal particles to the monoclinic form. Behind the advancing crack, a process zone forms in which all the tetragonal particles have transformed to the monoclinic form. The cumulative increase in volume exerts a closing force on the advancing crack, as well as a corresponding resistance to crack propagation that increases with crack length. Ceramics such as transformation-toughened zirconia (TTZ) are often referred to as ceramic steel because the strain, or change in dimension, in response to stress behaviour resembles that of steel instead of a brittle ceramic. Also, the underlying phase transformation is called martensitic, after a similar transformation in rapidly quenched steel to a phase known as martensite.

. Although other materials such as alumina can be transformation-toughened, zirconia (zirconium dioxide, ZrO2) is the prototype material for this process. Pure zirconia, upon cooling below 1,150° C (2,100° F), undergoes a dramatic 3 percent volume expansion as it transforms from a tetragonal form to a monoclinic form. This expansion can be used to advantage by dispersing extremely fine tetragonal particles in a matrix of cubic zirconia or alumina. The small size of the particles (less than 1 micrometre) and their intimate contact with the matrix induce the tetragonal structure to remain stable at room temperature. Ahead of an advancing crack, however, a stress field triggers the transformation of the embedded tetragonal particles to the monoclinic form. Behind the advancing crack, a process zone forms in which all the tetragonal particles have transformed to the monoclinic form. The cumulative increase in volume exerts a closing force on the advancing crack, as well as a corresponding resistance to crack propagation that increases with crack length. Ceramics such as transformation-toughened zirconia (TTZ) are often referred to as ceramic steel because the strain, or change in dimension, in response to stress behaviour resembles that of steel instead of a brittle ceramic. Also, the underlying phase transformation is called martensitic, after a similar transformation in rapidly quenched steel to a phase known as martensite.Prospects of toughened ceramics

Comparative toughness

Although toughened ceramics are far less tough than metals, they represent a vast improvement over conventional ceramics and glass. Fracture toughness is defined as the stress-intensity factor at a critical point where crack propagation becomes rapid. It is given the symbol KIc and is measured in units of megapascals times the square root of the distance measured in metres (MPa√m). With glass, an extremely brittle material, having a KIc value of 1, all other materials can be assigned values relative to that of glass. Metals thus have relative KIc's in the 30–45 range (aluminum alloys) or the 40–65 range (steels). In comparison, conventional ceramics have relative fracture toughnesses in the 3–4 range and are therefore brittle like glass. Ceramics with fibrous or interlocked microstructures and particle-reinforced composites fall in the 4–6 range. Whisker-reinforced and fibre-reinforced composites have toughnesses in the 8–10 and 10–25 range, respectively. Transformation-toughened ceramics fall in the 6–15 range. At such toughness large TTZ ball bearings can be repeatedly bounced on concrete floors without noticeable surface damage.

Limitations

Despite their superior properties, toughened ceramics have not achieved widespread use. One reason for this is that they are costly to produce. Therefore, they will not displace their metallic counterparts unless they display such cost-saving performance features as increased operating temperature or dramatically increased lifetime. Toughened ceramics also can lose their properties at elevated temperatures. As temperature rises, the driving force for the phase transformation in TTZ decreases and then disappears altogether. As a result, the material loses its toughness. Whiskers and fibres in ceramic-matrix composites are often susceptible to high-temperature oxidation. This virtually eliminates them as toughening agents, so that the ceramic matrix reverts to brittle behaviour. One of the challenges facing ceramic engineers is the engineering of tough ceramic microstructures that are stable at elevated temperatures.

Applications of advanced structural ceramics

Advanced ceramics are employed in a number of structural applications. These are described in the articles nuclear ceramics, bioceramics, tribological ceramics, and automotive ceramics. In addition, advanced ceramics provide enhanced performance in traditional ceramic applications; these are described in the articles refractory and abrasive.

Additional Reading

The section titled “Structural Applications for Technical, Engineering, and Advanced Ceramics,” in Theodore J. Reinhart (ed.), Engineered Materials Handbook, vol. 4, Ceramics and Glasses, ed. by Samuel J. Schneider (1991), pp. 959–1014, presents an overview of advanced structural ceramics. A good introduction to ceramics in general is provided by David W. Richerson, Modern Ceramic Engineering: Properties, Processing, and Use in Design, 2nd ed., rev. and expanded (1992). The processing of advanced ceramics is described in James S. Reed, Introduction to the Principles of Ceramic Processing (1988); I.J. McColm and N.J. Clark, Forming, Shaping, and Working of High Performance Ceramics (1988); George Y. Onoda, Jr., and Larry L. Hench, Ceramic Processing Before Firing (1978); and four sections of the Reinhart work cited above: “Ceramic Powders and Processing,” pp. 41–122; “Forming and Predensification, and Nontraditional Densification Processes,” pp. 123–241; “Firing/Sintering: Densification,” pp. 242–312; and “Final Shaping and Surface Finishing,” pp. 313–376.

- Cammaerts, Émile

- Camorra

- camouflage

- camp

- Campagna di Roma

- Campagnola, Domenico

- Campagnola, Giulio

- campaign furniture

- Campaign of Ilerda

- Campaldino, Battle of

- Campana, Dino

- Campanella, Roy

- Campanella, Tommaso

- Campania

- Campanian Stage

- Campani, Giuseppe

- campanile

- Campan, Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Genest

- Campanulaceae

- Campaspe River

- Campbell, Alexander

- Campbell-Bannerman, Sir Henry

- Campbell, Bebe Moore

- Campbell, David

- Campbell, Donald Malcolm