Togo

Introduction

officially Republic of Togo, French Togo, or République Togolaise

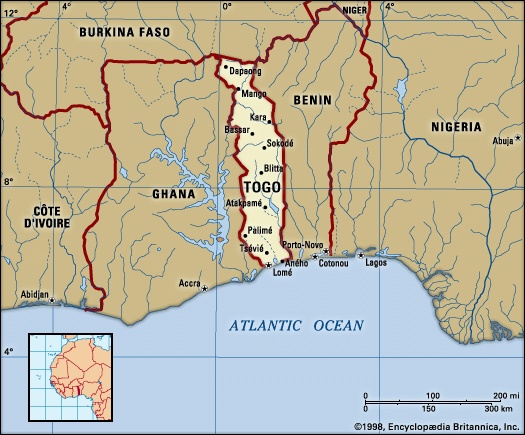

Togo, flag ofcountry of western Africa. From its 32-mile (51-kilometre) coastline on the Gulf of Guinea, Togo extends northward for about 320 miles between Ghana to the west and Benin to the east to its boundary with Burkina Faso in the north. Lomé, the capital, is the largest city and port.

The land

Relief, drainage, and soils

Togo consists of six geographic regions. The low-lying, sandy beaches of the narrow coastal region are backed by tidal flats and shallow lagoons, the largest of which is Lake Togo. Beyond the coast lies the Ouatchi Plateau, which stretches about 20 miles inland at an altitude of some 200 to 300 feet (60 to 90 metres). This is the region of the so-called terre de barre, a lateritic (reddish, leached, iron-bearing) soil.

Northeast of the plateau is a tableland, the highest altitudes reaching 1,300 to 1,500 feet. This region is drained by the Mono River and its tributaries, including the Ogou, and other smaller rivers. West and southwest of the tableland the terrain gradually rises toward the Togo Mountains, which run across central Togo from the south-southwest to the north-northeast. Part of a chain that begins in the Atakora Mountains of Benin, the range ends in the Akwapim Hills of Ghana. Mount Baumann (Baumann Peak) (Agou), which rises to about 3,235 feet (986 metres), is the highest mountain in Togo. Beyond the Togo Mountains to the north lies the Oti River sandstone plateau. This is a savanna region drained by the Oti River, one of the main tributaries of the Volta. To the far northwest is a higher region of granite and gneiss; the cliffs of Dapaong (Dapango) are located in this region.

Climate

Togo has a tropical climate. In the south the rainy seasons occur from mid-April through June and from mid-September through October. The narrow coastal zone, which receives about 35 inches (890 millimetres) of rain annually, is the driest region. The region of Kpalimé (Palimé), about 65 miles inland, receives the highest amount of rain—about 70 inches annually. The north has only one rainy season with an average rainfall of about 45 inches, mostly falling from June to the end of September; during the rest of the year the warm, dry harmattan (a dust-laden wind) predominates. Mean annual temperatures vary from 79° F (26° C) along the coast and in the mountains to 82° F (28° C) on the northern plateau. Daily minimum temperatures of about 68° F (20° C) are recorded in the mountains in August. Daily maxima of about 100° F (38° C) occur in the north during March and April at the end of the long dry season.

Plant and animal life

Savanna-type vegetation is predominant in Togo. On the southern plateaus large trees, including the baobab, are common, but they are rare in the north. The southwestern highland regions are covered with tropical forests, also found along the river valleys. The coastal zone is dotted with mangrove and reed swamps.

Wild animals are not found in great numbers, especially in the southern and central regions. A few lions, leopards, and elephants can be seen in the north. Monkeys, snakes, and lizards are numerous in many areas, and crocodiles and hippopotamuses abound in the rivers. In the Keran Forest Reserve near Sansanné-Mango in the north, there are wild herds of buffalo, asses, warthogs, antelope, and deer. Numerous species of birds and insects are found in the country. Fish caught off the coast include mackerel, bass, seabream, red snapper, triggerfish, dorado, ray, and sole, while crustaceans include shrimp and lobster.

Settlement patterns

The majority of Togo's population live in small villages scattered throughout the rural areas. A common sight along the coast is the rectangular houses built either of clay and timber or of coconut or palm branches and topped by double-eaved thatched roofs. Scattered throughout the coconut plantations, they are not far from the beaches. Inland in the south, thatched rectangular huts made of adobe are clustered around big trees and surrounded by earthen walls or fences made of palm branches. In the north, the traditional adobe or stone huts are circular and are topped by conical roofs or thatched turrets. They are usually gathered in units corresponding to family groups; often enclosed by earthen walls, they are sometimes interlinked. Distinctive of the northern Kara region is the high density of villages that stretch along the highway or climb up the slopes of the many hills.

Lomé, the largest urban centre, is spread along the coast. At its centre, there is a mixture of old and new commercial and administrative buildings. The traditional housing unit is the big, walled compound composed of a group of isolated rooms, each opening onto a courtyard.

Aného (Anécho), another coastal town, was once the country's leading European trade centre but is now declining. Other main towns include Tsévié and Tabligbo in the lowland plateau; Kpalimé, Atakpamé, Sokodé, Bassar (Bassari), and Kara (Lama-Kara) at the base of the Togo Mountains; and Sansanné-Mango (Mango) and Dapaong in the far north.

The people

The population of Togo comprises about 30 ethnic groups, many of whom are immigrants from other parts of western Africa. The groups indigenous to Togo live in the north and southwest. The northern groups include the following Gur (Gur languages)-speaking Voltaic peoples: the Gurma; the Natimba, Dye, and Konkomba; the Tamberma; the Basari; the Moba; the Losso (Naudem); the Kabre and Logba; and the Lamba (Namba); a small number of Atlantic (Atlantic languages)-speaking Fulani; and the Kebu (Akebu). In the southwest the indigenous Kwa peoples also belonging to the central Togo group are the Kposo (Akposso), the Adele, and the Ahlo.

The immigrants came from east, west, and north. The Ewe, who emigrated from Nigeria between the 14th and 16th century, form the major ethnic group. There are also some scattered Yoruba, mainly Ana. Groups who emigrated from present-day Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire since the 17th century include the Mina (Ga and Ané), the Ga-Dangme, the Kpelle and the Anyama, the Chakosi, and the Dagomba. The northern groups—the Kotokoli (or Temba), Gurma, and Mossi—entered mainly from Burkina Faso.

Most of the nation's non-Africans live in Lomé. They are mainly French. Brazilians, or Portuguese of Brazilian birth, constituted the original trading settlement in Togo, and today African-Brazilians are closely associated with economic and political development.

Although Christianity has profoundly marked the country, about half the population still adhere to traditional animistic beliefs and in the south participate in voudou (voodoo) cults. The main Protestant (Calvinistic) church has been governed for a long time by Togolese moderators. Since independence, the Roman Catholic church in Togo has been headed by a Togolese archbishop. There is also a growing Islamic population.

The economy

To encourage private investment, the Investment Code of 1965 guaranteed foreign investors the right of freely transferring abroad all investment capital and income. The code also provided for tax benefits for priority enterprises. The trend in the 1970s of direct state involvement in the economy changed in the early 1980s to a pattern of offering incentives for foreign investment and privatization of state enterprises.

Indirect taxes, almost entirely on imports and exports, account for most of the government's ordinary budget revenues. Direct taxes consist of an income tax, a progressive tax on all profits, taxes on wages paid by employers, a tax on rental values and land, and head taxes.

Unlike other former French territories, Togo has not extended preferential trade treatment to France and subsequently to the European Economic Community. This open-door, nondiscriminatory trade policy—together with the expanded production of phosphate and tropical produce—has contributed to the development of the economy.

Resources

Phosphate is the major mineral resource and by far the country's leading export item. The deposits at Hahoetoé and Kpogamé, directly northeast of Lomé, are mined by the government's Togolese Office of Phosphates. Togo is one of the world's largest phosphate producers. Marble is quarried by Sotoma (Société Togolaise de Marbres et de Matériaux), a mixed-economy company with shares held by the Togolese government and an Italian firm. Togo's considerable limestone reserves, also mined near Lomé, are utilized primarily for cement production.

Other mineral resources with commercial potential include iron ore, bauxite, uranium, chromite (an oxide of iron and chromium), gold, diamonds, rutile (titanium dioxide), manganese oxide, and kaolin (china clay). While the iron ore reserves are large, the metal content is only slightly more than 50 percent. The bauxite has a low mineral content.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

The variety of soils and climates enables Togo to grow a wide range of products. Export crops include cocoa beans, coffee, shea nuts, cotton, and palm kernels; staple crops are corn (maize), cassava, rice, yams, sorghum, millet, and peanuts (groundnuts).

Cattle, sheep, and pigs are raised in the plateau region and the north. Fishing is carried out on the coast and in the well-stocked inland rivers and ponds. Most of the catch is consumed locally. Forests, which cover about one-fourth of Togo's total area, are a source of tropical hardwoods and other products.

A government agency, the Office of Agricultural Products of Togo, has a monopoly on the foreign sale of Togolese products. Export sales are made by local firms in Paris and London, acting as agents of the Office.

Industry

Mining and quarrying dominate industry in Togo. Manufacturing in the past centred on the processing of agricultural commodities and the import substitution of consumer goods (textiles, footwear, beverages, and tires). In the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, major investments in heavy industrial schemes included a cement plant, a petroleum refinery, a steelworks, and a phosphoric acid plant, but some of these have since closed down.

Trade

Imports include machinery, transport equipment, food, construction materials, pharmaceuticals, and paper products. Low customs duties have encouraged significant smuggling of imported consumer goods to neighbouring countries with higher tariffs, especially Ghana. Besides phosphate and agricultural products, some refined petroleum and cement are exported. Togo's main trading partners are France, The Netherlands, and Germany.

Transportation

The three main road systems are the scenic coastal road between Ghana and Benin; the road from Lomé north to Burkina Faso; and roads serving the cocoa- and coffee-producing area of Kpalimé, Badou, and Atakpamé.

The government-owned national railway consists of four lines, all of which emanate from Lomé. One line connects Kpalimé with the capital; other lines run to Aného, Tabligbo, and Blitta.

Lomé is Togo's principal port. Its artificial harbour was inaugurated in 1968. A second port at Kpémé, about 22 miles northeast of Lomé, is used exclusively to handle phosphate shipments.

The international airport at Lomé links Togo with European and other African countries. A second international airport at Niamtougou in the north opened in the early 1980s. There are local airports in Atakpamé, Sokodé, Sansanné-Mango, and Dapaong.

Administration and social conditions

Government

The military coup d'état of 1967 abolished the constitution of 1963 and dissolved the National Assembly. Togo had been ruled since 1969 by the Rally of the Togolese People, the sole political party until 1991 when parties were legalized. A new constitution in 1992 established the president as head of state and an elected multiparty National Assembly. The president appoints the prime minister from the parliament majority.

The country is divided into five régions—Maritime, Plateaux, Centrale, Kara, and Savanes—for the purposes of economic planning. The five régions are subdivided into 21 préfectures, each of which is headed by a district chief assisted by a district council. Seven communes have been established—for the cities of Aného, Atakpamé, Bassar, Lomé, Kpalimé, Sokodé, and Tsévié, respectively.

The administrative apparatus is complemented by traditional authorities, which include tribal kings or chiefs, village chiefs, and heads of family groups. These traditional authorities play a role in the judicial system, dealing with certain questions of customary law. The judicial system, headed by a Supreme Court, consists of a number of law courts in which civil, commercial, administrative, and criminal cases are heard.

Education

Education is modeled after the French system. Togolese teachers, who have replaced French personnel to a large extent, are expected to adapt the system to the Togolese context. Primary and secondary education is provided by public or parochial schools.

The University of Benin at Lomé (founded in 1970) has schools of humanities and science and a university institute of technology. A school of architecture and town planning, also at Lomé, was founded in 1975 by the African and Mauritian Common Organization (OCAM).

Cultural life

Like other African peoples, the Togolese have a strong oral tradition. Little has been done, however, to promote vernacular literature. Before independence there were a few Togolese writers using French. Since independence, regional (especially Ewe) literature emerged with the works of several novelists and playwrights. Founded in 1967, the African Ballet of Togo has aimed at popularizing the finest traditional dances.

History

Until 1884 Togoland was an indeterminate buffer zone between the warring states of Asante and Dahomey. The only port was Petit Popo (Anécho, or Aného). Throughout the 18th century the Togo portion of the Slave Coast was held by the Danes.

German occupation

German missionaries arrived in Ewe territory in 1847, and German traders were soon established at Anécho. In 1884 Gustav Nachtigal (Nachtigal, Gustav), sent by the German government, induced a number of coastal chiefs to accept German protection. The protectorate was recognized in 1885, and its coastal frontiers with Dahomey and the Gold Coast were defined by treaties with France and Great Britain. German military expeditions (1888–97) met with little resistance, securing a hinterland the boundaries of which also were determined by treaties with France (1897) and Great Britain (1899).

Lomé, at the western end of the coast, was selected as the colonial capital in 1897, a modern town was laid out, and in 1904 a jetty was built. Three railways were constructed to open up the interior. Exploitation was confined to the coastal and central areas and was exclusively agricultural. Plantations were established both by the government and by private German corporations, but crop development was left mainly to the Togolese, assisted by agriculturists trained at a college in Nuatja (Notsé). Upwardly mobile Ewe were recruited into what was supposed to be Germany's Musterkolonie (model colony). Trade was chiefly in palm products, rubber, cotton, and cocoa. German administration was efficient but marred by its harsh treatment of Africans and use of forced labour.

On August 7, 1914, at the outset of World War I, British and (British Empire) French colonial troops from the Gold Coast and Dahomey invaded Togoland and on August 26 secured the unconditional surrender of the Germans. Thereafter the western part of the colony was administered by Britain, the eastern part by France. By an Anglo-French agreement of July 10, 1919, France secured the railway system and the whole coastline. After Germany renounced its sovereignty in the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations in 1922 issued mandates to Britain and France for the administration of their spheres.

League of Nations (Nations, League of) mandate

The northern part of the British-mandated territory was administered with the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, the southern part with the Gold Coast Colony. Although the British administration built roads connecting its sphere with the road system of the Gold Coast, the bulk of the territory's external trade passed over the railways of French Togo.

French Togo was administered by a commissioner assisted by a consultative executive council. When British Togo was attached to the Gold Coast, French Togo was formed into a distinct unit until 1934, when a kind of economic union was established with Dahomey; this was replaced in 1936 by a qualified integration with French West Africa that lasted 10 years. Agricultural development was pursued, and a planned settlement of the interior by the Kabre and other peoples was carried out. Peanut growing was introduced in the northern areas, and energetic action was taken against sleeping sickness.

After World War II French Togo sent a deputy to the French National Assembly, a counselor to the Assembly of the French Union, and two senators to the Council of the Republic. A representative assembly was concerned with internal affairs.

United Nations trusteeship

In 1946 the British and French governments placed their spheres of Togoland under UN trusteeship. After 1947 the Ewe people in southern Togoland represented to the Trusteeship Council that either their territories or the whole of Togoland should be brought under a common administration. These proposals were difficult to implement because Ewe also inhabited the southeastern part of the Gold Coast Colony and because not all the people of southern Togoland were Ewe. The British colony was also rapidly advancing toward self-government, and the incorporation of the northern part of the British sphere with the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast had reunited the Dagomba and Mamprusi kingdoms, both of which had been cut in two by the pre-1914 boundary. Following a plebiscite held under UN auspices on May 9, 1956, the British trust territory of Togoland was on December 13 incorporated into the Gold Coast (although in the southern districts of Ho and Kpandu the Ewe vote showed a two-to-one majority in favour of continued British trusteeship). The Gold Coast and Togoland together were renamed Ghana and achieved independence in 1957.

Independence

French Togoland became an autonomous republic within the French Union on August 30, 1956. This status was confirmed (despite Ewe opposition) by a plebiscite held in October under French auspices. Nicolas Grunitzky was appointed premier. Following UN representations, elections in April 1958 favoured complete independence and rejected Grunitzky's Togolese Progress Party in favour of Sylvanus Olympio (Olympio, Sylvanus)'s Togolese National Unity Party. Togo became independent on April 27, 1960.

After the 1961 elections, which established a presidential form of government, Olympio became the first president. He maintained economic cooperation with France. Togo became a member of the Organization of African Unity (OAU, now the African Union) in 1963 and in 1965 subscribed to the renewed Joint African and Malagasy Organization, which provided for economic, political, and social cooperation among French-speaking African states.

Ghanaian pressure for the integration of Togo with Ghana was resisted by the Togolese and led to strained relations between the two republics, including a trade embargo imposed by Ghana. Olympio's increasingly harsh rule and policy of fiscal austerity came to an end on January 13, 1963. Having rejected petitions to integrate into the national army Togolese noncommissioned officers recently demobilized from France's colonial armies, Olympio was shot at the gates of the U.S. Embassy (while seeking sanctuary) by Sergeant Étienne Gnassingbé Eyadéma (Eyadéma, Gnassingbé) (later called Gnassingbé Eyadéma). Grunitzky was invited to return from exile and assume the presidency, and he was confirmed in office in subsequent elections that also created a new constitution and legislature. Most of the noncommissioned officers were integrated into an expanded army—many as commissioned officers.

Cabinet infighting, aggravated in the south by Ewe feelings that with Olympio's assassination they had lost power to Grunitzky's largely pro-northern administration, led to chronic instability. On January 13, 1967, Eyadéma, then a lieutenant colonel and chief of staff, once again seized power and dissolved all political parties. Though relying primarily on the support of his kinsmen in the north and the largely northern-staffed army, Eyadéma's rule was stabilized by a number of other factors. phosphate exports dramatically improved the economic picture, allowing the regime to satisfy regional and ethnic interests and to begin the first serious effort at transforming the countryside. Meticulous ethnic balancing of the cabinet and an open-door economic policy further attracted support from prospering traders (and smugglers into Ghana), and by 1972 Eyadéma felt secure enough to seek popular legitimation via a presidential plebiscite. In 1974 the phosphate industry was nationalized, generating increased state revenues. On December 30, 1979, the first legislative elections since 1967 were held under a new constitution that formally placed Togo under civilian, one-party rule headed by President Eyadéma and the Rally of the Togolese People. Legislative elections were held again in 1985, and Eyadéma was elected to a second seven-year term the following year. A commission was established in 1990 to draft a new constitution, which prompted the legalization of political parties in 1991 and the adoption of a democratic constitution in 1992. However, in the first multiparty elections in August 1993, Eyadéma was reelected president amid allegations of electoral fraud, and the same charges were leveled in 1998. Protests over the 1998 elections continued into 1999, affecting the legislative elections held that year, and instigated an independent inquiry by the UN and the OAU. Their joint report, issued in 2001, found that the government had systematically violated human rights during the 1998 presidential election. Eyadéma's reelection in 2003 was again clouded by accusations of fraud; however, these claims were refuted by international observers.

Despite his long tenure, Eyadéma's regime was not without its opponents. Most of these were Ewe from the south (including the self-exiled sons of Olympio) rebelling against the northerner Eyadéma and the cult of personality that progressively surrounded him. The opposition sponsored conspiracies to topple Eyadéma and was held responsible for a number of bombings in Lomé. Civil unrest, in the form of strikes and sometimes-violent demonstrations, plagued Eyadéma as well. The regime's patronage base—and, by extension, its stability—was also undermined in the 1980s and '90s by an economic downturn. Falling global prices for phosphates led to sharply lower state revenues, while growing corruption and massive expenditures on the bloated civil service and inefficient public enterprises strained the fiscal resources of the state. Togo's costly government-owned industries were dismantled or privatized, and the country's heavy national debt was often rescheduled. In 2004 the European Union agreed to resume the flow of monetary aid to Togo, which had been halted in 1993 as a protest against the poor governance and lack of democracy in the country, if Togo met specified criteria addressing such issues as election reform and the repeal of controversial press laws.

After Eyadéma's unexpected death in February 2005, his son, Faure Gnassingbé, was hastily installed as president by the military—an action critics characterized as a coup. After weeks of international condemnation, Gnassingbé stepped down and a presidential election was held in April. He was declared the winner of that election, which was initially certified by some international observers as free and fair but later marred as reports of considerable fraud emerged. The opposition refused to immediately concede defeat, and hundreds of people were killed and thousands fled from the country in the violent post-election aftermath.

Additional Reading

Robert Cornevin, Histoire du Togo, 3rd ed. rev. and expanded (1969), covers geography, prehistory, ethnology, and history. Samuel Decalo, Historical Dictionary of Togo, 2nd ed. (1987), is a useful reference with an extensive bibliography. Ethnographic studies include Jean-Claude Froelich, Pierre Alexandre, and Robert Cornevin, Les Populations du Nord-Togo (1963); Raymond Verdier, Le Pays kabiyé (1982); and François de Medeiros (ed.), Peuples du Golfe du Bénin (1984). The political evolution of the country since independence is presented in Samuel Decalo, “The Benevolent General: Military Rule in Togo,” in his Coups and Army Rule in Africa (1976), pp. 87–121; and in the issue titled “Togo Authentique,” Politique Africaine, 27 (September–October 1987). Arthur J. Knoll, Togo Under Imperial Germany, 1884–1914 (1978), is a study of the German colonial era. Comi M. Toulabor, Le Togo sous Eyadéma (1986); and Andoch Nutépé Bonin, Le Togo du sergent en général (1983), discuss the period of military rule.

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, 1900-2005 3

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, 1900-2005 4

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, 1900-2005 5

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, AD 1900-2000

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, AD 1900-2000 1

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, AD 1900-2000 2

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, AD 1900-2000 3

- Religious Adherents in the United States of America, AD 1900-2000 4

- Religious Adherentsnin the United States of America, AD 1900-2000

- religious dress

- religious experience

- Religious Science

- religious symbolism and iconography

- religious syncretism

- relish

- Relizane

- Relizian Stage

- R.E.M.

- rem

- remainder

- Remak, Robert

- remanent magnetism

- Remarque, Erich Maria

- Rembang

- Rembert Dodoens