Afghanistan

Introduction

Afghanistan, flag of

landlocked, multiethnic country located in the heart of south-central Asia. Lying along important trade routes connecting southern and eastern Asia to Europe and the Middle East, Afghanistan has long been a prize sought by empire builders, and for millennia great armies have attempted to subdue it, leaving traces of their efforts in great monuments now fallen to ruin. The country's forbidding landscape of deserts and mountains has laid many imperial ambitions to rest, as has the tireless resistance of its fiercely independent peoples—so independent that the country has failed to coalesce into a nation but has instead long endured as a patchwork of contending ethnic factions and ever-shifting alliances.

landlocked, multiethnic country located in the heart of south-central Asia. Lying along important trade routes connecting southern and eastern Asia to Europe and the Middle East, Afghanistan has long been a prize sought by empire builders, and for millennia great armies have attempted to subdue it, leaving traces of their efforts in great monuments now fallen to ruin. The country's forbidding landscape of deserts and mountains has laid many imperial ambitions to rest, as has the tireless resistance of its fiercely independent peoples—so independent that the country has failed to coalesce into a nation but has instead long endured as a patchwork of contending ethnic factions and ever-shifting alliances.

landlocked, multiethnic country located in the heart of south-central Asia. Lying along important trade routes connecting southern and eastern Asia to Europe and the Middle East, Afghanistan has long been a prize sought by empire builders, and for millennia great armies have attempted to subdue it, leaving traces of their efforts in great monuments now fallen to ruin. The country's forbidding landscape of deserts and mountains has laid many imperial ambitions to rest, as has the tireless resistance of its fiercely independent peoples—so independent that the country has failed to coalesce into a nation but has instead long endured as a patchwork of contending ethnic factions and ever-shifting alliances.

landlocked, multiethnic country located in the heart of south-central Asia. Lying along important trade routes connecting southern and eastern Asia to Europe and the Middle East, Afghanistan has long been a prize sought by empire builders, and for millennia great armies have attempted to subdue it, leaving traces of their efforts in great monuments now fallen to ruin. The country's forbidding landscape of deserts and mountains has laid many imperial ambitions to rest, as has the tireless resistance of its fiercely independent peoples—so independent that the country has failed to coalesce into a nation but has instead long endured as a patchwork of contending ethnic factions and ever-shifting alliances.The modern boundaries of Afghanistan were established in the late 19th century in the context of a rivalry between imperial Britain and tsarist Russia that Rudyard Kipling termed the “Great Game.” Modern Afghanistan became a pawn in struggles over political ideology and commercial influence. In the last quarter of the 20th century, Afghanistan suffered the ruinous effects of civil war greatly exacerbated by a military invasion and occupation by the Soviet Union (1979–89). In subsequent armed struggles, a surviving Afghan communist (communism) regime held out against Islamic insurgents (1989–92), and, following a brief rule by mujahideen groups, an austere movement of religious students—the Taliban—rose up against the country's governing parties and warlords and established a theocratic regime (1996–2001) that soon fell under the influence of a group of well-funded Islamists led by an exiled Saudi Arabian, Osama bin Laden (bin Laden, Osama). The Taliban regime collapsed in December 2001 in the wake of a sustained U.S.-dominated military campaign aimed at the Taliban and fighters of bin Laden's al-Qaeda (Qaeda, al-) organization. Soon thereafter, anti-Taliban forces agreed to a period of transitional leadership and an administration that would lead to a new constitution and the establishment of a democratically elected government.

The capital of Afghanistan is its largest city, Kabul. A serene city of mosques and gardens during the storied reign of the emperor Bābur (1526–30), founder of the Mughal Dynasty, and for centuries an important entrepôt on the Silk Road, Kabul lay in ruins following the long and violent Afghan War. So, too, fared much of the country, its economy in shambles and its people scattered and despondent. By the early 21st century an entire generation of Afghans had come to adulthood knowing nothing but war.

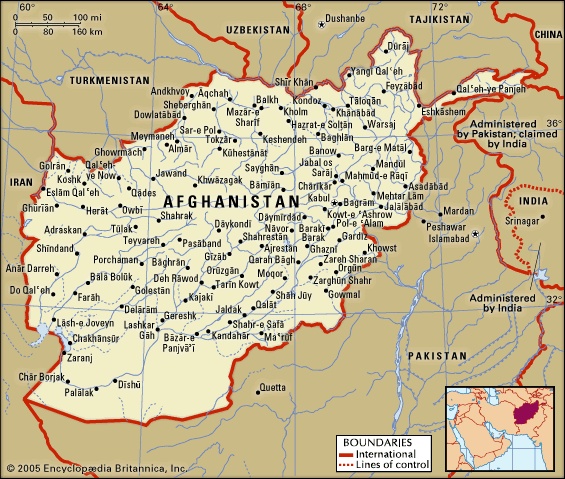

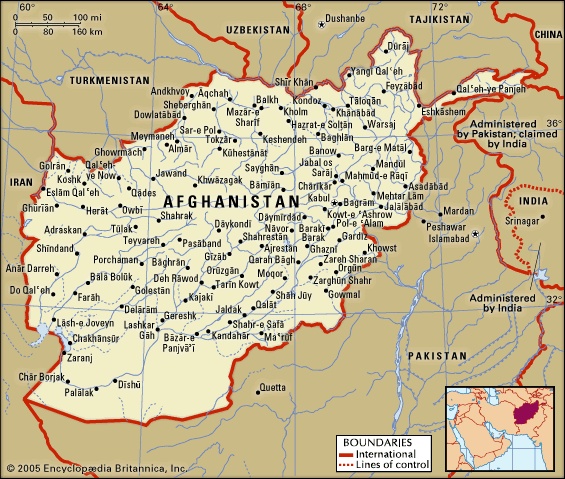

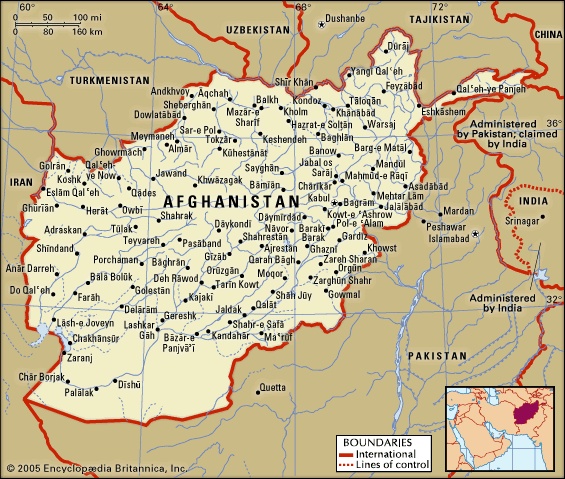

Land

Afghanistan is completely landlocked—the nearest coast lies along the Arabian Sea, about 300 miles (480 km) to the south—and, because of both its isolation and its volatile political history, it remains one of the most poorly surveyed areas of the world. It is bounded to the east and south by Pakistan (including those areas of Kashmir administered by Pakistan but claimed by India), to the west by Iran, and to the north by the Central Asian states of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. It also has a short border with Xinjiang, China, at the end of the long, narrow Vākhān (Wakhan Corridor), in the extreme northeast. Its overall area is roughly twice that of Norway.

Relief

The Hindu Kush

Afghanistan's (Afghanistan) shape has been compared to a leaf, of which the Vākhān strip, nestled high in the Pamirs, forms the stem. The outstanding geographic feature of Afghanistan is its mountain range, the Hindu Kush. This formidable range creates the major pitch of Afghanistan from northeast to southwest and, along with its subsidiary ranges, divides Afghanistan into three distinct geographic regions, which roughly can be designated as the central highlands, the northern plains, and the southwestern plateau. When the Hindu Kush itself reaches a point some 100 miles (160 km) north of Kabul, it spreads out and continues westward as a series of ranges under the names of Bābā, Bāyan, Sefīd Kūh (Paropamisus), and others, and each section in turn sends spurs in different directions. One of these spurs is the Torkestān Mountains, which extend northwestward. Other important ranges include the Sīāh Kūh, south of the Harīrūd, and the Ḥeṣār Mountains, which stretch northward. A number of other ranges, including the Mālmand and Khākbād, extend to the southwest. On the eastern frontier with Pakistan, several mountain ranges effectively isolate the interior of the country from the moisture-laden winds that blow from the Indian Ocean. This accounts for the dryness of the climate.

Afghanistan's (Afghanistan) shape has been compared to a leaf, of which the Vākhān strip, nestled high in the Pamirs, forms the stem. The outstanding geographic feature of Afghanistan is its mountain range, the Hindu Kush. This formidable range creates the major pitch of Afghanistan from northeast to southwest and, along with its subsidiary ranges, divides Afghanistan into three distinct geographic regions, which roughly can be designated as the central highlands, the northern plains, and the southwestern plateau. When the Hindu Kush itself reaches a point some 100 miles (160 km) north of Kabul, it spreads out and continues westward as a series of ranges under the names of Bābā, Bāyan, Sefīd Kūh (Paropamisus), and others, and each section in turn sends spurs in different directions. One of these spurs is the Torkestān Mountains, which extend northwestward. Other important ranges include the Sīāh Kūh, south of the Harīrūd, and the Ḥeṣār Mountains, which stretch northward. A number of other ranges, including the Mālmand and Khākbād, extend to the southwest. On the eastern frontier with Pakistan, several mountain ranges effectively isolate the interior of the country from the moisture-laden winds that blow from the Indian Ocean. This accounts for the dryness of the climate.Physiographic regions

The central highlands—actually a part of the Himalayan (Himalayas) chain—include the main Hindu Kush range. Its area of about 160,000 square miles (414,000 square km) is a region of deep, narrow valleys and lofty mountains, some peaks of which rise above 21,000 feet (6,400 metres). High mountain passes, generally situated between 12,000 and 15,000 feet (3,600 to 4,600 metres) above sea level, are of great strategic importance and include the Shebar Pass, located northwest of Kabul where the Bābā Mountains branch out from the Hindu Kush, and the storied Khyber Pass, which leads to the Indian subcontinent, on the Pakistan border southeast of Kabul. The Badakhshān area in the northeastern part of the central highlands is the location of the epicentres for many of the 50 or so earthquakes that occur in the country each year.

The northern plains region, north of the central highlands, extends eastward from the Iranian border to the foothills of the Pamirs, near the border with Tajikistan. It comprises some 40,000 square miles (103,000 square km) of plains and fertile foothills sloping gently toward the Amu Darya (the ancient Oxus River). This area is a part of the much larger Central Asian Steppe (Steppe, the), from which it is separated by the Amu Darya. The average elevation is about 2,000 feet (600 metres). The northern plains region is intensively cultivated and densely populated. In addition to fertile soils, the region possesses rich mineral resources, particularly deposits of natural gas.

The southwestern plateau, south of the central highlands, is a region of high plateaus, sandy deserts, and semideserts. The average elevation is about 3,000 feet (900 metres). The southwestern plateau covers about 50,000 square miles (130,000 square km), one-fourth of which forms the sandy Rīgestān region. The smaller Mārgow Desert of salt flats and desolate steppe lies west of Rīgestān. Several large rivers cross the southwestern plateau; among them are the Helmand River and its major tributary, the Arghandāb.

Most of Afghanistan lies between 2,000 and 10,000 feet (600 and 3,000 metres) in elevation. Along the Amu Darya in the north and the delta of the Helmand River in the southwest, the elevation is about 2,000 feet (600 metres). The Sīstān depression of the southwestern plateau is roughly 1,500 to 1,700 feet (450 to 500 metres) in elevation.

Drainage

Practically the entire drainage system of Afghanistan is enclosed within the country. Only the rivers in the east, which drain an area of 32,000 square miles (83,000 square km), reach the sea. The Kābul River, the major eastern stream, flows into the Indus River in Pakistan, which empties into the Arabian Sea of the Indian Ocean. Almost all the other important rivers of the country originate in the central highlands region and empty into inland lakes or dry up in sandy deserts. The major drainage systems are those of the Amu Darya, Helmand, Kābul, and Harīrūd.

The Amu Darya, 1,578 miles (2,540 km) long, originates in the glaciers of the Pamirs and drains an area of approximately 93,000 square miles (241,000 square km) in the northeastern and northern parts of the country. It forms the frontier between Afghanistan and the republics of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan for about 600 miles (1,000 km) of its upper course. Two of its major Afghan tributaries, the Kowkcheh and the Qondūz, rise in the mountains of Badakhshān and Kondoz provinces. The Amu Darya becomes navigable from its confluence with the Kowkcheh, 60 miles (100 km) west of the city of Feyẕābād.

The northwestern drainage system is dominated by the Harīrūd River, originating on the western slopes of the Bābā Mountains, at an elevation of 9,000 feet (2,750 metres). The river flows westward, just south of Herāt and across the broad Herāt Valley. After irrigating the fertile lands of the valley, the Harīrūd turns north about 80 miles (130 km) west of Herāt and forms the border between Afghanistan and Iran for a distance of 65 miles (105 km). It then crosses into Turkmenistan and disappears in the Karakum Desert.

The principal river in the southwest is the Helmand (Helmand River), which rises in the Bābā Mountains about 50 miles (80 km) west of Kabul and has a course of some 715 miles (1,150 km). With its many tributaries, mainly the Arghandāb, it drains more than 100,000 square miles (259,000 square km). In its course through southern Afghanistan, the Helmand flows north of Rīgestān, crosses the Mārgow Desert, and empties into highly saline seasonal lakes in the Sīstān depression along the Afghan-Iranian border.

The largest drainage system in the southeastern region is that of the Kābul River, which flows eastward from the slopes of the Paghmān range to join the Indus River in Pakistan. Its major tributary in the south is the Lowgar.

Afghanistan has few lakes of any considerable size. The two most important are the Ṣāberī (a salt flat that occasionally is inundated) in the southwest and the saline Lake Īstādeh-ye Moqor, situated 60 miles (100 km) south of Ghaznī in the southeast. There are five small lakes in the Bābā Mountains known as the Amīr lakes; they are noted for their unusual shades of colour, from milky white to dark green, a condition caused by the underlying bedrock.

Soils

The country possesses extremes in the quality of its soils. The central highlands have desert-steppe or meadow-steppe types of soil. The northern plains have extremely rich, fertile, loesslike soils, while the southwestern plateau has infertile desert soils except along the rivers, where alluvial deposits can be found. Erosion is much in evidence in the central highlands, especially in the regions affected by seasonal monsoons and heavy precipitation.

Climate

In general, Afghanistan has extremely cold winters and hot summers, typical of a semiarid steppe climate. There are many regional variations, however. While the mountain regions of the northeast have a subarctic climate with dry, cold winters, the mountainous areas on the border of Pakistan are influenced by the Indian monsoons, usually coming between July and September and bringing maritime tropical air masses with humidity and rains. In addition, strong winds blow almost daily in the southwest during the summer. Local variation is also produced by differences in elevation. The weather in winter and early spring is strongly influenced by cold air masses from the north and the Atlantic low from the northwest; these two air masses bring snowfall and severe cold in the highlands and rain in the lower elevations.

Temperatures vary widely in Afghanistan. Daytime highs over 95 °F (35 °C) occur in the drought-ridden southwestern plateau region. In Jalālābād, one of the hottest localities in the country, the highest temperature, 120 °F (49 °C), has been recorded in July. In the high mountain areas, January temperatures may drop to 5 °F (−15 °C) and below, while at the city of Kabul, located at an elevation of 5,900 feet (1,800 metres), a low of −24 °F (−31 °C) has been recorded.

In the mountains the annual mean precipitation increases from west to east; there, as in the southeastern monsoon region, it averages about 16 inches (400 mm). National precipitation extremes have been recorded in the Sālang Pass of the Hindu Kush, with a highest annual precipitation of 53 inches (1,350 mm), and in the arid region of Farāh in the west, with only 3 inches (75 mm) per year. Most of the country's precipitation occurs from December to April; in the highlands snow falls from December to March, while in the lowlands it rains intermittently from December to April or May. The summer months are hot, dry, and cloudless everywhere but in the monsoon region.

Plant and animal life

Vegetation is sparse in the southern part of the country, particularly toward the west, where dry regions and sandy deserts predominate. Trees are rare, and only in the rainy season of early spring is the soil covered with flowering grasses and herbs. The plant cover becomes denser toward the north, where precipitation is more abundant, and at higher elevations the vegetation is almost luxuriant, particularly in the mountainous region north of Jalālābād, where the climate is influenced by the monsoons. The high mountains abound with large forest trees, among which conifers, such as pine and fir, predominate. Some of these trees are 180 feet (55 metres) high. The average elevation for the fir line is over 10,000 feet (3,000 metres). At lower elevations, somewhere between 5,500 and 7,200 feet (1,700 and 2,200 metres), cedar is abundant; below the fir and cedar lines, oak, walnut, alder, ash, and juniper trees can be found. There are also shrubs, several varieties of roses, honeysuckle, hawthorn, and currant and gooseberry bushes.

Most of the wild animals of the subtropical temperate zone inhabit Afghanistan. Large mammals, formerly abundant, are now greatly reduced in numbers, and the tiger has disappeared. There is still a great variety of wild animals roaming the mountains and foothills, including wolves, foxes, striped hyenas, and jackals. Gazelles, wild dogs, and wild cats, such as snow leopards, are widespread. Wild goats, including the markhor (Cabra falconeri; prized for its long, twisted horns) and the ibex (with long, backward-curving horns), can be found in the Pamirs, and wild sheep, including the urial and argali (or Marco Polo sheep), inhabit the Pamirs and the Hindu Kush. Brown bears are found in the mountains and forests. Smaller animals, such as mongooses, moles, shrews, hedgehogs, bats, and several species of kangaroo rats (jerboas), may be found in the many isolated, sparsely populated areas.

Birds of prey include vultures, which occur in great numbers, and eagles. Migratory birds abound during the spring and fall seasons. There are also many pheasant, quail, cranes, pelicans, snipe, partridge, and crows.

There are many varieties of freshwater fish in the rivers, streams, and lakes, but their numbers are not great except on the northern slopes of the Hindu Kush, where the rivers are well stocked with brown trout.

People

Ethnic groups

No national census has been conducted in Afghanistan since a partial count in 1979, and years of war and population dislocation have made an accurate ethnic count impossible. Current population estimates are therefore rough approximations, which show that Pashtuns (Pashtun) comprise somewhat less than two-fifths of the population. The two largest Pashtun tribal (tribe) groups are the Durrānī and Ghilzay. Tajiks (Tajik) are likely to account for some one-fourth of Afghans and Ḥazāra nearly one-fifth. Uzbeks (Uzbek) and Chahar Aimaks each account for slightly more than 5 percent of the population and Turkmen an even smaller portion.

The Hindu Kush divides the country into northern and southern regions, which can be further subdivided on the basis of topography, national and ethnolinguistic settlement patterns, or historical tradition. Northern Afghanistan, for example, may be subdivided into the Badakhshān-Vākhān region in the east and the Balkh-Meymaneh region in the west. The east, which is mainly a conglomeration of mountains and high plateaus, is inhabited chiefly by Tajiks. Although there are also pockets of Tajiks in other areas of the country, in the east they are sedentary in the plains—where they are mostly farmers and artisans—and semisedentary in the higher valleys. The Tajiks are not divided into clear-cut tribal groups. There are also small numbers of Kyrgyz in the Vākhān in the extreme northeast, where they practice herding.

The west, which is mostly plains of comparatively low elevation, contains a mixture of peoples in which Uzbeks (Uzbek) and Turkmen, both of Turkic origin, predominate. The Uzbeks are usually farmers, while the Turkmen have traditionally been seminomadic herders. The Uzbeks are the largest Turkic-speaking group in Afghanistan. There are also other smaller Turco-Mongolian groups.

Southern Afghanistan can be subdivided into four regions—those of Kabul, Kandahār, Herāt, and Ḥazārajāt. The Kabul region combines the area drained by the Kābul River and the high plateau of eastern Afghanistan, bounded in the south by the Gowmal (Gumal) River. This region is the main corridor connecting the other regions and their peoples. The traditional homeland of the Pashtun lies in an area east, south, and southwest of Kabul, but this group is also well represented in the west and north. The Pashtun are divided into a number of tribes, some sedentary and others nomadic, and many live in contiguous territory in Pakistan. This region is also inhabited by Tajiks, and the Nuristani (Nūristāni) inhabit an area of some 5,000 square miles (13,000 square km) north and east of Kabul.

The Kandahār region is a sparsely populated part of southern Afghanistan. The Durrānī Pashtun, who have formed the traditional nucleus of Afghanistan's social and political elite, live in the area around the city of Kandahār itself, which is located in a fertile oasis near the Arghandāb River, and the Ghilzay inhabit the region between Kabul and Kandahār. In addition, there are a small number of Balochi (Baloch) (Baluchi) and Brahui people in the region.

The region of Herāt, or western Afghanistan, is inhabited by a mixture of Tajiks, Pashtun, and Chahar Aimak. The life of the region revolves around the city of Herāt. The Chahar Aimak are probably of Turkic or Turco-Mongolian origin, judging by their physical appearance and their housing (Mongolian-style yurts). They are located mostly in the western part of the central mountain region.

The mountainous region of Ḥazārajāt occupies the central part of the country and is inhabited principally by the Ḥazāra. Because of the scarcity of land, however, many have migrated to other parts of the country. Although Ḥazārajāt is located in the heart of the country, its high mountains and poor communication facilities make it the most isolated part of Afghanistan.

Languages

The people of Afghanistan form a complex mosaic of ethnic and linguistic groups. Pashto (Pashto language) and Persian (Dari (Dari language)), both Indo-European languages, are the official languages of the country. More than two-fifths of the population speak Pashto, the language of the Pashtuns, while about half speak some dialect of Persian. While the Afghan dialect of Persian is generally termed “Dari,” a number of dialects are spoken among the Tajik, Ḥazāra, Chahar Aimak, and Kizilbash peoples, including dialects that are more closely akin to the Persian spoken in Iran (Farsi) or the Persian spoken in Tajikistan (Tajik). The Dari and Tajik dialects contain a number of Turkish and Mongolian words, and the transition from one dialect into another across the country is often imperceptible. Bilingualism is fairly common, and the correlation of language to ethnic group is not always exact. Some non-Pashtuns, for instance, speak Pashto, while a larger number of Pashtuns, particularly in urban areas, have adopted the use of one of the dialects of Persian.

Other Indo-European languages, spoken by smaller groups, include Western Dardic (Dardic languages) (Nuristani or Kafiri), Balochi (Balochi language), and a number of Indic and Pamiri languages spoken principally in isolated valleys in the northeast. Turkic languages, a subfamily of the Altaic languages, are spoken by the Uzbek and Turkmen peoples, the most recent settlers, who are related to peoples from the steppes of Central Asia. The Turkic languages are closely related; within Afghanistan they include Uzbek, Turkmen, and Kyrgyz, the last spoken by a small group in the extreme northeast. Afghanistan has very small ethnic groups of Dravidian speakers. Dravidian languages are spoken by the Brahuis (Brahui), residing in the extreme south.

The present population of Afghanistan contains a number of elements, which, in the course of history and as a result of large-scale migration and conquests, have been superimposed on one another. Dravidians, Indo-Aryans, Greeks, Scythians, Arabs, Turks, and Mongols have at different times inhabited the country and influenced its culture and ethnography. Intermixture of the two principal linguistic groups is evident in such peoples as the Ḥazāra and Chahar Aimak, who speak Indo-European languages but have physical and cultural traits usually associated with the Turkic and Mongol peoples of Central Asia.

Religion

Virtually all the people of Afghanistan are Muslims (Islāmic world), of whom some three-fourths are Sunnites of the Ḥanafī branch. The others, particularly the Ḥazāra and Kizilbash, follow either Ithnā ʿAsharī (Ithnā ʿAsharīyah) or Ismāʿīlī (Ismāʿīlīte) Shīʿite Islam. Sufism (Ṣūfism) is practiced widely. The Nuristani are descendants of a large ethnic group, the Kafir, who were forcibly converted to Islam in 1895; the name of their region was then changed from Kāfiristān (“Land of the Infidels”) to Nūrestān (“Land of Light”). There are also a few thousand Hindus and Sikhs.

Virtually all the people of Afghanistan are Muslims (Islāmic world), of whom some three-fourths are Sunnites of the Ḥanafī branch. The others, particularly the Ḥazāra and Kizilbash, follow either Ithnā ʿAsharī (Ithnā ʿAsharīyah) or Ismāʿīlī (Ismāʿīlīte) Shīʿite Islam. Sufism (Ṣūfism) is practiced widely. The Nuristani are descendants of a large ethnic group, the Kafir, who were forcibly converted to Islam in 1895; the name of their region was then changed from Kāfiristān (“Land of the Infidels”) to Nūrestān (“Land of Light”). There are also a few thousand Hindus and Sikhs.Settlement patterns

Urban settlement

Most urban settlements have grown along the road that runs from Kabul southwestward to Kandahār, then northwest to Herāt, northeast to Mazār-e Sharīf, and southeast back to Kabul. The rural population of farmers and nomads is distributed unevenly over the rest of the country, mainly concentrated along the rivers. The most heavily populated part of the country is between the cities of Kabul and Chārīkār. Other concentrations of people can be found east of the city of Kabul near Jalālābād, in the Herāt oasis and the valley of the Harīrūd in the northwest, and in the valley of the Qondūz River in the northeast. The high mountains of the central part of the country and the deserts in the south and southwest are sparsely populated or uninhabited.

The major cities of Afghanistan are Kabul, Kandahār, Herāt, Baghlān, Jalālābād, Kondoz, Chārīkār, and Mazār-e Sharīf. Kabul is the administrative capital of the country, located south of the Hindu Kush at the crossroads of the trade routes between the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia and between the Middle East and East Asia. It is built on both sides of the Kābul River and is the main centre of economic and cultural activity. Kandahār, second to Kabul in population, is located on the Asian Highway in the south-central part of the country, between Kabul and Herāt. Kandahār became the first capital of modern Afghanistan in 1747 under Aḥmad Shah Durrānī (Aḥmad Shāh Durrānī).

Rural settlement

Sedentary farmers usually live in small villages, most of them scattered near irrigated land in the valleys of major rivers. These villages, as a rule, are built in the form of small forts. Each fort-village contains several mud houses inhabited by closely connected families who form a defensive community.

The semisedentary farmers, who breed livestock and raise a few crops, live in the high alpine valleys. Since cultivable land there is scarce, they live in scattered isolated hamlets. Each household owns a few head of livestock, which are moved in summer to the highland pastures. The people usually divide themselves into two groups in summer: one group remains in the hamlet to tend the crops, while the other accompanies the livestock to the highlands.

The nomads (nomadism) are mainly Pashtun herders; there are also several thousand Balochi and Kyrgyz nomads. They move in groups (tribes or clans) from summer to winter pasturages, living in tents and, while on the move, packing their belongings on the backs of camels, donkeys, and cattle. Between one-sixth and one-fifth of the total population have in the past been classified as nomadic. Since 1977, however, some nomads have been settled in the plains north of the Hindu Kush or in the area of the Helmand Valley (irrigation) Project. More significant, the long period of civil conflict has disrupted the migratory pattern of nomads, and, as a result, their numbers have declined sharply.

Demographic trends

The establishment of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in 1978, the Soviet (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) invasion of the country the following year, and the continuing conflict following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 severely disrupted the country's population patterns. Civil war and the destruction of towns and villages caused mass movements of people in two major directions—emigration, mainly to Pakistan and Iran, or internal resettlement to the relative safety of Kabul. The population of Kabul is estimated to have doubled in size. Kabul has grown to encompass almost half the urban population of the country. Afghanistan's population is mainly rural; more than two-fifths of the population is under 15 years of age. Life expectancy is about 47 years for men and 46 years for women.

During the late 1980s some 6 million people—probably one-third of the Afghan population at the time—were refugees (refugee). Some 3.5 million were living in Pakistan, and perhaps another 2 million were in Iran. Although many were repatriated during the 1990s, the numbers of those internally and externally displaced rose again after 2000 as a result of continued civil strife, economic hardship, and an extended and severe drought.

The economy

Overview

When Afghanistan began to plan the development of its economy with Soviet (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) assistance in the mid 1950s, it lacked not only the necessary social organization and institutions for modern economic activities but also the managerial and technical skills. The country was at a much lower stage of economic development than most of its neighbours. Between 1956 and 1979, however, the country's economic growth was guided by several five-year and seven-year plans and was aided by extensive foreign assistance. This aid, primarily from the Soviet Union and the United States, accounted for more than four-fifths of government investment and development expenditures during that period. Roads, dams, power plants, and factories were constructed, irrigation projects carried out, and education broadened. When foreign assistance declined in the 1970s, the sale of natural gas to the Soviet Union, albeit at a bargain price, more than compensated in financing budget expenditures.

The Soviet legacy

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the subsequent civil war severely disrupted the country's economic development. Agricultural production declined, food shortages were reported, and industrial output stagnated—with the exception of natural gas production and some other industries considered essential by the Soviet Union. The private sector during the Soviet period encompassed primarily agriculture and livestock breeding. There formerly had been a mixed pattern of small, medium, and large landholdings, but this system underwent drastic change, particularly after 1978. The bulk of the trade and transport as well as most manufacturing was in the hands of private entrepreneurs until the late 1970s, when these sectors of the economy were nationalized. Public enterprise was confined to foreign trade, mining, and some industries.

A balanced budget was achieved with revenue derived principally from the sale of natural gas and from foreign loans and grants. Expenditures were mainly for government ministries, the developmental budget, and interest on foreign debt. The socialist government was committed to developing a mixed, guided economy. In practice, however, the effectiveness of this policy was limited by a paucity of government resources, a cumbersome bureaucracy, and a shortage in technical personnel.

Economic collapse

However low the Afghan economy had sunk during the period of communist (communism) rule, it was to decline even more under subsequent mujahideen and Taliban governments. After more than two decades of war, and in the face of the Taliban's harsh social policies, few educated Afghans with even rudimentary technical skills remained in the country. In effect, any remains of a modern economy—at least a formal, legal one—largely collapsed during the 1990s. Public and private investment in productive enterprises was rare. Foreign aid agencies and groups, governmental and nongovernmental, provided what few services were available, but these met only basic humanitarian needs.

During the 1990s economic activity flourished mostly in illicit enterprises, such as growing opium poppies for heroin production and smuggling goods. The taxing of Afghan-Pakistani trade contributed much revenue to the Taliban's war chest. As the Taliban's prime source of income, it overshadowed the taxing of opium trafficking. But that part of trade—encompassing a massive smuggling of duty-free goods—had crippled local industry and revenue collections and created temporary food shortages, inflation, and increased corruption in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries. Poppy cultivation was the major source of income for farmers, but they shared little in its full profits. However, the drug (drug abuse) economy did provide essential revenues that enabled the Taliban to pursue its war effort. By the late 1990s Afghanistan had become the world's largest producer of opium and was thought to be the main source of heroin exported to Europe, North America, and elsewhere. Although the Taliban successfully banned the growing of opium poppies in 2000, drug trafficking continued due to large reserves of opium warehoused in the country, and it was not until that regime's collapse that an interim government attempted systematically to eradicate the narcotics trade.

Most of the population continues to be engaged in agriculture, though the destruction caused by war has been a force for urbanization by driving many from the countryside. Many Afghans brought up in refugee camps lack the farming skills they need to survive, and the country's agricultural sector is in great need of restoration, particularly its destroyed and degraded irrigation system. The road system is similarly damaged, and domestic energy sources need to be developed for both export income and domestic use.

Agriculture and forestry

Agriculture and animal husbandry, mainly consisting of subsistence farming and pastoral nomadism, are, in more normal times, the most important elements of the gross domestic product (GDP), accounting for nearly half of its total value. Afghanistan is essentially a pastoral country. Only about one-eighth of the total land area is arable, and only about half of the arable acreage is cultivated annually. Much of the arable area consists of fallow cultivated land or steppes and mountains that serve as pastureland. Since much of the land is arid or semiarid, about half of the cultivated land is irrigated. Traditionally, as much as 85 percent of the population drew its livelihood from a rural economy, mostly as farmers.

The greater profits found in the illegal market for drugs and the smuggling trade have cut heavily into traditional agriculture and food production. Afghanistan now has to import much of its foodstuffs from Pakistan. Prior to the period when poppy growing became widespread, most cultivated land was planted with cereals, with wheat as the chief crop. Other food grains customarily planted were corn (maize), rice, and barley. Cotton was also important, both for a domestic textile industry—when such an industry existed—and for export. Fruits and nuts have also been important export items.

Animal husbandry produces meat and dairy products for local consumption; skins, especially those of the famous karakul, and wool (both for export and for domestic carpet weaving) are also important products. Livestock includes sheep, cattle, goats, donkeys, horses, camels, buffalo, and mules. About two-thirds of the annual milk production is from cows, the rest from sheep and goats. In addition to the country's many other difficulties, a drought in 2000 killed off some four-fifths of the livestock in southern Afghanistan and crippled the remaining food production.

Forests cover about 3 percent of the total land area and are found mainly in the eastern part of the country and on the southern slopes of the Hindu Kush. Woodlands in the east consist mainly of conifers, providing timber for the building industry as well as some wild nuts for export. Other trees, especially oaks, are used as fuel. North of the Hindu Kush are pistachio trees, the nuts of which are a traditional export. Deforestation has become a major problem, as much of the country's timber has been harvested for fuel—because of shortages brought on by 20 years of warfare—and for illegal export.

Resources and power

Extensive surveys have revealed the existence of a number of minerals of economic importance. The most significant discovery has been natural gas deposits, with large reserves near Sheberghān near the Turkmenistan border, about 75 miles (120 km) west of Mazār-e Sharīf. The Khvājeh Gūgerdak and Yatīm Tāq fields were major producers, with storage and refining facilities. Until the 1990s, pipelines delivered natural gas to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and to a thermal power plant and chemical fertilizer plant in Mazār-e Sharīf.

Petroleum resources have proved to be insignificant. Many coal deposits have been found in the northern slopes of the Hindu Kush. Major coal fields are at Maʿdan-e Karkar and Eshposhteh, between Kabul and Mazār-e Sharīf, and Qalʿeh-ye Sarkārī, southwest of Mazār-e Sharīf. In general, however, Afghanistan's energy resources, including its large reserves of natural gas, remain untapped, and fuel shortages are chronic.

High-grade iron ore has been discovered at Ḥājjī Gak, northwest of Kabul. Copper has been mined at ʿAynak, near Kabul, and uranium in the mountains near Khvājah Rawāsh, east of Kabul. There are deposits of copper, lead, and zinc near Kondoz; beryllium in Khāṣ Konaṛ; chrome ore in the Lowgar River valley near Herāt; and the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli in Badakhshān. Afghanistan also has deposits of rock salt, beryl, barite, fluorspar, bauxite, lithium, tantalum, gold, silver, asbestos, mica, and sulfur. Taxation of mined and traded lapis lazuli and emeralds helped finance anti-Taliban forces during the civil war.

The development of Central Asian natural gas and oil resources has sparked international interest in Afghanistan as a route for pipelines (pipeline) to markets in South Asia and beyond. If built, a pipeline could carry gas and, later, oil from Turkmenistan over some 1,100 miles (1,750 km), mostly through Afghanistan, to Multan in Pakistan for transshipment. Such a pipeline could become a major source of income for Afghanistan and also offer a source of training and employment to Afghans.

Afghanistan is potentially rich in hydroelectric resources. However, the seasonal flow of the country's many streams and waterfalls—torrential in spring, when the snow melts in the mountains, but negligible in summer—necessitates the costly construction of dams and reservoirs in remote areas. The country's negligible demand for electricity renders such projects unprofitable except near large cities or industrial centres. The potential of hydroelectricity has been tapped substantially only in the Kabul-Jalālābād region.

Manufacturing

In peaceful times, manufacturing is based mainly on agricultural and pastoral raw materials. Most important is the cotton textile industry. The country also produces rayon and acetate fibres. Other manufactured products are cement, sugar, vegetable oil, furniture, soap, shoes, and woolen textiles. A nitrogenous fertilizer plant, based on natural gas, has been constructed in Mazār-e Sharīf, and phosphate fertilizers are also produced. A cement factory continues to operate in Pol-e Khomrī. In addition, a number of traditional handicrafts are practiced in Afghanistan, including carpet weaving, which in times past accounted for a fair proportion of the country's export earnings.

Finance

The largest bank in the country, the Bank of Afghanistan, became the centre of the formal banking system. It formerly played an important role in determining and implementing the country's financial policies. Traditionally, private money traders provide nearly all the services of a commercial bank. The currency, the afghani, underwent rampant inflation beginning in the 1990s, and as a result precious metals and gems became a common form of currency for large transactions. A sanction imposed in 1999 by the United Nations (UN) against the Taliban government froze government accounts abroad and closed the few branches of Afghan banks outside the country. Despite these measures, the Taliban and their al-Qāʿidah (Qaeda, al-) supporters (al-Qāʿidah is an Islamic extremist group that found refuge under the Taliban) removed large quantities of bullion and currency from Afghanistan during the U.S. military campaign of 2001, virtually bankrupting the country. Thus, it became imperative that the post-Taliban regime establish a functioning banking and monetary system with a sound new currency as a major component of national reconstruction.

Trade

Total annual imports have customarily exceeded exports. Prior to the fall of Afghanistan's communist regime, roughly two-thirds of exports went to the former Soviet republics to the north, and much of the rest went to the United Kingdom and Germany. The Soviet state was also the leading source of imports, followed by Japan, Singapore, China, and India. The principal export, natural gas, flowed mostly to the Soviet Union until pipelines were closed. Traditional exports are dried fruits, nuts, carpets, wool, and karakul pelts, and imports include vehicles, petroleum products, sugar, textiles, processed animal and vegetable oils, and tea. Since the mid 1990s Pakistan and Iran have served as the major suppliers of consumer goods.

Services

Until the collapse of the communist regime in 1992, the service sector—including public administration, military spending, and retail sales—accounted for less than one-fourth of GDP. Although there have been no official statistics since then, government spending fell sharply over the decade, and, like other segments of the economy, retail sales suffered from the country's general economic malaise. Purchasing power in the post-Taliban period began to recover with the revival of government programs that were funded mainly by international donors.

Labour and taxation

The bulk of the population in the rural areas consists of small farmers exploiting their tiny plots of land. The majority of the city and town dwellers are artisans, small traders, or government employees. The industrial labour force, always small, is now hardly visible, and labour unions have failed to develop. Traditional loyalties to families and tribes (tribe) are stronger than those to workers' organizations.

The Afghan government has traditionally received much of its revenue from foreign aid—particularly during the Soviet era—and as a consequence the Afghan people have generally been lightly taxed. Taxation during the mujahideen and Taliban period often took the form of levies placed on the illicit cross-border trade between Pakistan and other countries, on cultivating opium poppies and manufacturing heroin, and on extracting and exporting semiprecious stones. Following the defeat of the Taliban in 2001, the interim government relied largely on foreign aid and subsidies from donor nations.

Transportation and telecommunications

Being a landlocked country, Afghanistan depends primarily on transit facilities from its neighbours for its international trade. It lacks railways, has few navigable rivers, and relies on roads as the mainstay of its transport system. These factors drive up transportation costs and also add to the difficulty of integrating the transport system of the country with those of its neighbours. Nevertheless, in the 1960s major efforts were directed toward upgrading the highway system and connecting the main trading centres of the country with one another, as well as with the railheads or road networks of neighbouring countries.

The road network of Afghanistan connects railheads in Gushgy, Turkmenistan, and Termiz, Uzbekistan, with those at Chaman and Peshawar, Pakistan, respectively, and provides for direct overland transit between the countries to the north and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. The most important Afghan highways are those connecting Kabul with Shīr Khān, on the northern border, and with Peshawar. Other paved roads link Kandahār, Herāt, and Mazār-e Sharīf with Kabul and with frontier towns of Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. During the civil war, however, the road system was severely damaged from the fighting and from disrepair. Its rehabilitation has become a high priority in any program of national reconstruction.

Despite the rapid development of motor transport, camels and donkeys are still commonly used as draft animals. In the countryside many people have not abandoned their cherished horses, which are an important source of prestige.

Almost all provincial centres have at least a seasonally operable airport. There are international airports at Kabul and Kandahār. Afghanistan, however, has limited air service and only one airline, the national carrier, Ariana Afghan Airlines. UN restrictions imposed in 1999 and again in 2001, aimed at punishing the Taliban government for its alleged support of international terrorism, limited international routes for Ariana and prohibited other airlines from scheduling flights into the country.

Afghanistan's communications infrastructure is one of the least developed in the world. Telephone service is sparse, with only one main telephone line per thousand persons. As of 2002 there was no cellular telephone or Internet service in any part of the country. Radio receivers are fairly pervasive, with roughly one radio receiver per 10 people. Afghans who have access to shortwave radio listen to international broadcasts—including the Voice of America's Dari and Pashto programs and the BBC Pashto Service—which are primary sources of information. The number of televisions per capita is only one per hundred residents. Wealthy Afghans have satellite dishes and are able to receive foreign broadcasts; domestic television reception is limited to Kabul.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

Until the mid 20th century, Afghanistan was ruled by the absolute power of the king. Two constitutions were promulgated, in 1923 and 1931, both affirming the power of the monarchy. The constitution of 1964, however, provided for a constitutional monarchy based on the separation of executive, legislative, and judicial authorities. A military coup in 1973 overthrew the monarchy, abolished the constitution of 1964, and established the Republic of Afghanistan. The Grand Assembly (Loya Jirga) adopted a new constitution in February 1977, but it was abrogated in 1978 when another coup established the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, governed by the Afghan Revolutionary Council. Political turmoil continued, marked by a third coup in September 1979, a massive invasion of troops from the Soviet Union, and the installation of a socialist government in December 1979. Another new constitution—promulgated in 1987 and revised in 1990—changed the name of the country back to the Republic of Afghanistan, reaffirmed its nonaligned status, strengthened the post of president, and permitted other parties to participate in government. The communist (communism) regime, which had managed to hold power after the Soviet forces departed early in 1989, fell in 1992, and a coalition of victorious mujahideen parties formed a government (recognized by the UN) and named the country the Islamic State of Afghanistan. The new government was driven from the capital in 1996 by a movement based in Kandahār and calling itself the Taliban. The Taliban leaders promptly changed the name of the country to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. In December 2001 the Taliban was toppled by a coalition of Afghan parties supported by the United States. Neither of these postcommunist governments, both espousing the supremacy of Islamic law, had promulgated a new constitution for the country.

Many Afghans continue to believe that “the highest manifestation of the will of the people of Afghanistan” is vested in the institution of the Loya Jirga. As a specially convened national assembly, it has traditionally held the power to amend and interpret the constitution, declare war, and adopt decisions on the most critical national issues. Because the Loya Jirga is closely associated with the rule of monarchy, it is revered most by those Afghans, especially in the dominant Pashtun community, who seek a more ethnically representative government than was initially installed following the Taliban's overthrow.

Political process

Those government institutions established during the reign of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (1880–1901) laid the groundwork for the modern Afghan state. They gave primacy to a strong military, centralized government control from Kabul, and signaled the primacy of the Pashtun as the country's ruling group.

Local government

In practice, however, Afghan governments have never succeeded in extending their rule very deeply at the local level. This reality has meant that local influentials and power brokers would not challenge the state, and the state, in turn, would refrain from trying to interfere with them. Whatever the regime in power, a high degree of autonomy has allowed local areas to pursue economic activities and to follow tribal (tribe) and localized law and customs. To administer the government's few extractive and allocative powers, the country was divided administratively into provinces, each headed by a centrally appointed governor. The provinces were further subdivided into districts and subdistricts headed by appointed officials.

Informal institutions and justice

Governments have also worked through largely informal consultative bodies at the local level, such as community councils (shūrās) and tribal assemblies (jirgas), many of which have continued to function regardless of changes in national politics. In the absence of an effective central government, Afghan communities have their own social norms, but none so elaborate as Pashtun tribal law, known as Pashtunwali. With the advent of the Taliban, Islamic courts and an Islamic administration of justice through interpretation of the law by clergy (ʿulamāʾ) assumed greater prominence. These changes have widely replaced the authority once exercised by traditional local leaders, or khans.

Weak central government

Afghanistan has relied far more on foreign subsidies and export taxes than on internal taxes to finance its limited scope of activities. As in other rentier states, the authorities were better able to distribute resources than to collect them. It was unnecessary for national government institutions to be very effective, since there was little policy to implement. If called upon to enforce a more active government, the existing institutions were bound to invite challenge and be prone to collapse. The most far-reaching and ultimately disastrous attempt to expand the penetration of the Kabul government occurred during the early years of communist rule that began in 1978 and eventually led to civil war and chaos.

Security

Following the collapse of the communist regime in 1992, government security apparatuses quickly dissolved. Individual mujahideen factions—formerly funded by foreign interests wishing to overthrow the regime—maintained their own militias and skirmished over control of the capital city and the countryside. Central government control extended little farther than Kabul itself, and law and order broke down almost entirely. The Taliban's emergence can be traced largely to the absence of security and to the exhaustion of the population from years of civil war. Under Taliban rule—which after 1998 covered all but a small area of the northeast—the roads were secure and personal safety improved for most Afghans. However, armed Taliban devotees also kept close watch for any signs of irreligion and executed harsh punishments on perceived offenders. In fighting that continued in the northeast—between the Taliban and a coalition of mujahideen factions known as the Northern Alliance—ethnic cleansing and war atrocities were perpetrated by both sides.

The security environment in the post-Taliban period has been threatened by many factors. Thousands of land mines (land mine) and large quantities of unexploded ordnance continue to litter the countryside. The return of many warlords expelled by the Taliban and the emergence of new power brokers spawned by the civil war has fragmented authority across the country. Regional commanders have sizable militias that they can use to compete over territory and resources, and small groups of Taliban and al-Qāʿidah (Qaeda, al-) fighters have remained capable of mounting guerrilla raids. The presence of international peacekeeping forces and other military units, although limited in their number and scope of operation, has precluded the most serious armed conflict and enhanced the authority of the central government.

Health and welfare

Based on the levels of infant mortality and life expectancy, Afghanistan has one of the least-developed health care systems in the world. The absence of potable water in most parts of the country is responsible for the widespread incidence of waterborne diseases. No more than one-eighth of the population, mostly in urban areas, had access to safe water during the 1990s. Only a small number have access to health care. Medical training is nonexistent, and the medical aid that is available is provided principally by international and nongovernmental organizations. Services offered by the government are minimal. The major proportion of medical services is concentrated in Kabul, and many rural areas do not have hospitals or doctors. Moreover, upon their arrival to power, the Taliban prohibited women—who at that time constituted a significant portion of trained medical workers—from working in that field, further debilitating an already weakened health care sector. There is no welfare system provided by the state, and the care and tending of the wounded from a generation of warfare—particularly the many thousands maimed by the vast number of land mines still found in the country—is a major social problem.

Based on the levels of infant mortality and life expectancy, Afghanistan has one of the least-developed health care systems in the world. The absence of potable water in most parts of the country is responsible for the widespread incidence of waterborne diseases. No more than one-eighth of the population, mostly in urban areas, had access to safe water during the 1990s. Only a small number have access to health care. Medical training is nonexistent, and the medical aid that is available is provided principally by international and nongovernmental organizations. Services offered by the government are minimal. The major proportion of medical services is concentrated in Kabul, and many rural areas do not have hospitals or doctors. Moreover, upon their arrival to power, the Taliban prohibited women—who at that time constituted a significant portion of trained medical workers—from working in that field, further debilitating an already weakened health care sector. There is no welfare system provided by the state, and the care and tending of the wounded from a generation of warfare—particularly the many thousands maimed by the vast number of land mines still found in the country—is a major social problem.Housing

Afghanistan's climatic and ethnic diversity has contributed to a wide variety of traditional habitations, particularly among the country's large rural population. Nomadic (nomadism) and transhumant groups have traditionally relied on yurts in the north—these are generally found among the Turkic and Mongol peoples—and tents in the south. The latter are favoured among the Pashtun groups. In the northern and western parts of the country, traditional sedentary settlements often have consisted of fortified villages of stone and mud-brick known as qalʿahs (“fortresses”), whereas in the northern and eastern mountain regions wooden, multistoried dwellings were customary among the Nuristani.

Until the modern period, urban dwellings were located within modest-sized walled cities, unchanged for centuries in their basic layout. It was only in the 20th century that urban centres began to spill outside the city walls and to take on characteristics associated with Western models, including high-rises, paved roads, and city services. Urban life deteriorated rapidly after the collapse of the communist regime, and a number of cities suffered severe damage to their infrastructures during the 1990s and early 21st century. By that time, few city services—electricity, water, sewage disposal—remained intact. Regardless, a large number of people fled the countryside, seeking shelter from the civil war. These people remained poorly housed and, lacking a central government, were forced to rely on private means for shelter. Rebuilding the country's housing stock has been one of the major tasks in national reconstruction.

Education

Education is free at all levels, and elementary education is officially compulsory wherever it is provided by the state. Nonetheless, even in the best of years, less than one-fourth of all Afghan children have attended school. Although there are primary schools throughout the country, there are secondary schools in only the provincial and some district centres. Under the Taliban, opportunities for schooling declined, and instruction was devoted mostly to Qurʾānic studies. Public education for girls virtually disappeared. In the late 1990s less than half of the male population was estimated to be literate, and probably no more than one in seven women.

Higher education has been limited to two institutions: Kabul University, founded in 1946 by the incorporation of a number of faculties, the oldest of which is the faculty of medicine, established in 1932, and the University of Nangarhār, established in Jalālābād in 1963. The civil war interfered with their operation, especially during the 1990s and again during the U.S. military campaign in 2001.

Cultural life

Afghanistan has a rich cultural heritage covering more than 5,000 years and absorbing elements from many cultures, especially those of Iran (Persia) and India. Even elements of Greek culture can be traced to the Hellenistic Age. This blend of cultures flourished at many points in Afghan history, notably under the reign of the Mughal emperors, when Kabul and Herāt emerged as important centres of art and learning. Largely because of its almost complete isolation from the outside world, however, little in art, literature, or architecture was produced between the 16th and early 20th centuries. Because most Afghans live outside the cities, their mode of living can be described as peasant tribal. kinship is the basis of social life and determines the patriarchal character of the community.

Afghans are also identified by their qawm, a term that can refer to affinity with almost any kind of social group. It essentially divides “us” from “them” and helps to distinguish members of one large ethnic or tribal group, or one clan or village, from another. Particular responsibilities and advantages go with membership, and the stability of social and political institutions may vary with their qawm composition.

Daily life and social customs

Religion has long played a paramount role in the daily life and social customs of Afghanistan. Even under the mujahideen leaders, Afghanistan appeared to be on a course of Islamization: the sale of alcohol was banned, and women were pressured to cover their heads in public and adopt traditional Muslim dress. But far more stringent practices were imposed as the Taliban enforced its Islamic code in areas under its control. These measures included banning television sets and most other forms of entertainment. Men who failed to grow beards and leave them untrimmed were fined and jailed—full beardedness being perceived by extremists as the mark of a Muslim—and little mercy was shown to convicted criminals. These and other policies were not widely popular, and the Taliban was subject to reproach at home and abroad for its inability to build a national administrative structure. But, in the absence of viable alternatives, most Afghans appeared to accept Taliban dictates for the more orderly society it brought.

Daily life for Afghan women has changed radically in recent years. In the 1960s the wearing of a veil became voluntary, and women found employment in offices and shops; some women also received a university education. The situation changed, however, after 1992 and particularly following the Taliban's capture of Kabul in 1996. Authorities closed down girls' schools and forced women to give up employment in nearly all occupations. Strong penalties were applied against women who were not fully covered in the streets or who were found in the company of males unrelated to them.

Today, in the post-Taliban era, daily life for most Afghans revolves around the exigencies of rebuilding a war-ravaged state. With increasing stability has come a greater and steadier food supply, but, in general, poor nutrition among Afghans has remained a serious cause of concern, especially in light of the neglect and destruction wrought upon the agricultural system during the war and the extended drought since the late 1990s. The staple of the Afghan diet is bread (nān), most commonly flat and oblong in shape and typically eaten when freshly removed from an earthen oven. Traditional cuisine consists of a variety of roast meats or meat pies (sanbūseh), stewed vegetables, rice pilaf, and a thick noodle soup (āsh) accompanied by fresh fruit and an assortment of yogurt-based sauces. The wide absence of clean drinking water and of adequate sanitation has ensured continuation of a high mortality rate, especially among young children. Outside the large cities, electricity is reserved for the privileged few.

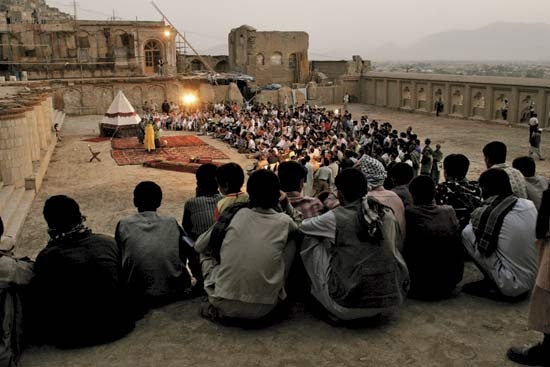

On the brighter side of daily life, the ban enforced by the Taliban on most forms of entertainment has been lifted, and the social atmosphere has become more relaxed. Afghans are again enjoying activities from kite flying to football, and photography is no longer prohibited. Though facilities are minimal, schools have been reopened—including those for girls—and women are once again entering the workforce. However, urban women have continued to wear the chador (or chadri, in Afghanistan), the full body covering mandated by the Taliban. This has been true even of those women of the middle class (most in Kabul) who had shed that garment during the communist era. Some men have shaved or trimmed their beards, but, aside from disregarding the style of turban associated with the Taliban, most have continued to dress traditionally—generally in the loose, baggy trousers typical of many parts of South and Central Asia, over which are worn a long overshirt and a heavy vest.

On the brighter side of daily life, the ban enforced by the Taliban on most forms of entertainment has been lifted, and the social atmosphere has become more relaxed. Afghans are again enjoying activities from kite flying to football, and photography is no longer prohibited. Though facilities are minimal, schools have been reopened—including those for girls—and women are once again entering the workforce. However, urban women have continued to wear the chador (or chadri, in Afghanistan), the full body covering mandated by the Taliban. This has been true even of those women of the middle class (most in Kabul) who had shed that garment during the communist era. Some men have shaved or trimmed their beards, but, aside from disregarding the style of turban associated with the Taliban, most have continued to dress traditionally—generally in the loose, baggy trousers typical of many parts of South and Central Asia, over which are worn a long overshirt and a heavy vest.The arts and cultural institutions

In music and dance, a revival of traditional folksinging has gone hand in hand with the imitation of modern Western and Indian music. Afghan music is different from Western music in many ways, particularly in its scales, note intervals, pitch, and rhythm, but it is closer to Western than to Asian music. Afghans celebrate their religious or national feast days, and particularly weddings, by public dancing. The performance of the attan dance in the open air has long been a feature of Afghan life. It became the national dance of the Pashtun and then of the entire country. Under the Taliban regime, however, all performances of music and dance—and even listening to or watching the same—were forbidden as un-Islamic.

Afghanistan's literary heritage is among the richest in Central Asia and is heir to a number of ethnic and linguistic traditions. Herāt, in particular, was a noted centre of Persian literary and scholarly pursuit; the Arabic-language author al-Hamadhānī (Hamadhānī, al-) settled there in the 10th century, as did the famous Persian-language poet Jāmī 500 years later. The theologian Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (Fakhr ad-Dīn ar-Rāzī) settled in Herāt in the 12th century, and in the following century the city of Balkh, once a great centre of learning, was the birthplace of the renowned poet Jalāl al-Dīn al-Rūmī (Rūmī) (although the latter left the region at a young age). The great Afghan chieftain and poet Khushḥāl Khan Khaṭak founded Pashto literature in the 17th century.

Archaeological research carried out since 1922 has uncovered many fine works of art of the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods. A revival of the traditional arts and an interest in new forms of expression have given a new dynamism to artistic creation. Of the new painters, some draw direct inspiration from the Herāt school of the 15th-century Timurid period; others are influenced by Western styles. Between the early 1950s and mid 1970s the government encouraged the restoration and redecoration of some of the old monuments of architectural value. However, the world-renowned ancient statues of Buddha in the caves of Bamiyan in central Afghanistan were destroyed in 2001 after the Taliban condemned them as idolatrous. The destruction was denounced worldwide.

Archaeological research carried out since 1922 has uncovered many fine works of art of the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods. A revival of the traditional arts and an interest in new forms of expression have given a new dynamism to artistic creation. Of the new painters, some draw direct inspiration from the Herāt school of the 15th-century Timurid period; others are influenced by Western styles. Between the early 1950s and mid 1970s the government encouraged the restoration and redecoration of some of the old monuments of architectural value. However, the world-renowned ancient statues of Buddha in the caves of Bamiyan in central Afghanistan were destroyed in 2001 after the Taliban condemned them as idolatrous. The destruction was denounced worldwide.The School of Fine Arts was established in Kabul in the 1930s. In architecture, the traditional Timurid techniques are preserved, particularly in the design of the exterior walls of mosques or tombs. Handicrafts include the world-renowned Afghan carpets and copper utensils.

Afghanistan's cultural institutions suffered greatly during the period of civil war, particularly under the successive mujahideen and Taliban regimes; most are now either defunct or in abeyance. In February 2002, however, the National Gallery of Art reopened its doors after having managed to hide many of the treasures under its care during the Taliban rule.

Sports and recreation

Afghanistan's traditional sports are individualistic and generally martial—even the childhood pastime of kite flying takes on a competitive edge, as youths often engage in contests to sever the kite strings of competitors. Wrestling, for individual and group honour, is universal, and shooting, both for game and for sport, is widespread. The sturdy and agile Afghan hound, popular in the West for its beauty, originally was bred for speed, agility, and hunting ability. The foremost sport in terms of popularity is indisputably the game of buzkashī. Often termed the Afghan national pastime, this rugged contest pits horsemen—sometimes in teams but often as individuals—against one another in a challenge to secure the headless carcass of a goat or calf (weighing about 50–100 pounds 【20–40 kg】) and carry it to a goal while simultaneously fending off competitors.

Western-style team sports never gained widespread popularity in Afghanistan, but the country made its first Olympic appearance in the 1936 Summer Games. It has since fielded teams only intermittently, and its last appearance was in the Summer Games of 1988. Afghanistan has never sent athletes to the Winter Games.

Media and publishing

Traditionally, the regimes that have ruled Afghanistan have had little tolerance for a free press. This was especially true under the Taliban. Since the Taliban's demise, the local press has exploded with new publications. Dozens of new papers and magazines have appeared, about one-third government-controlled and most weeklies. High production costs and a shortage of printing facilities has left the country with only one regularly appearing daily newspaper, a state-owned publication, Arman. The country's low rate of literacy has limited the number of readers, but the long-standing practice of reading newspapers aloud in public places has greatly expanded the number of Afghans who have access to the printed word. Censorship has not been widely practiced by the interim government.

History

Variations on the word Afghan may be as old as a 3rd-century-AD Sāsānian reference to “Abgan.” The earliest Muslim reference to the Afghans probably dates to 982, but tribes related to the modern Afghans have lived in the region for many generations. For millennia the land now called Afghanistan has been the meeting place of four cultural and ecological areas: the Middle East, Central Asia (Central Asia, history of), South Asia, and East Asia.

Prehistory

Paleolithic (Paleolithic Period) (Old Stone Age) peoples probably roamed Afghanistan as early as 100,000 years ago. The earliest definite evidence of human occupation was found in the cave of Darra-i-Kur in Badakhshān, where a transitional Neanderthal skull fragment in association with Mousterian-type tools was discovered; the remains are of the Middle Paleolithic Period, dating to about 30,000 years ago. Caves near Āq Kupruk yielded evidence of an early Neolithic (Neolithic Period) culture (c. 9000–6000 BC) based on domesticated animals. Archaeological research since World War II has revealed Bronze Age sites, dating both before and after the Indus civilization of the 3rd to the 2nd millennium BC. There was trade with Bronze Age Mesopotamia and Egypt, and the main export from the Afghan area was lapis lazuli from the mines of Badakhshān. In addition, a site with definite links to the Indus civilization has been excavated at Shortughai near the Amu Darya, northeast of Kondoz.

Historical beginnings (to the 7th century AD)

The Achaemenids (Achaemenian Dynasty) and the Greeks

In the 6th century BC the Achaemenian ruler Cyrus II (the Great) established his authority over the area. Darius I (the Great) consolidated Achaemenian rule of the region through the provinces, or satrapies, of Aria (in the region of modern Herāt), Bactria (Balkh), Sattagydia (modern Ghaznī to the Indus River), Arachosia (Kandahār), and Drangiana (Sīstān).

Alexander the Great overthrew the Achaemenids and conquered most of the Afghan satrapies before he left for India in 327 BC. Ruins of an outpost Greek (Hellenistic Age) city founded about 325 BC were discovered at Ay Khānom, at the confluence of the Amu Darya and Kowkcheh River. Excavations there produced inscriptions and transcriptions of Delphic precepts written in a script influenced by cursive Greek. Greek decorative elements dominate the architecture, including an immense administrative centre, a theatre, and a gymnasium. A nomadic raid about 130 BC ended the Greek era at Ay Khānom.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the eastern satrapies passed to the Seleucid (Seleucid kingdom) dynasty, which ruled from Babylon. About 304 BC the territory south of the Hindu Kush was ceded to the Maurya (Mauryan empire) dynasty of northern India. Bilingual rock inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic (the official language of the Achaemenids) found at Kandahār and Laghmān (in eastern Afghanistan) date from the reign of Ashoka (Aśoka (Ashoka); c. 265–238 BC, or c. 273–232 BC), the Maurya dynasty's most renowned emperor. Diodotus (Diodotus II), a local Greco-Bactrian (Bactria) governor, declared the Afghan plain of the Amu Darya independent about 250 BC; Greco-Bactrian conquerors moved south about 180 BC and established their rule at Kabul and in the Punjab. The Parthians (Parthia) of eastern Iran also broke away from the Seleucids, establishing control over Sīstān and Kandahār in the south.

The Kushāns (Kushan dynasty)

About 135 BC a loose confederation of five Central Asian nomadic tribes known as the Yuezhi wrested Bactria from the Bactrian Greeks. These tribes united under the banner of the Kushān (Kushan dynasty) (Kuṣāṇa), one of the five tribes, and conquered the Afghan area. The zenith of Kushān power was reached in the 2nd century AD under King Kaniṣka (Kaniska) (c. AD 78–144), whose empire stretched from Mathura in north-central India beyond Bactria as far as the frontiers of China in Central Asia.

The Kushāns were patrons of the arts and of religion. A major branch of the Silk Road—which carried luxury goods and facilitated the exchange of ideas between Rome, India, and China—passed through Afghanistan, where a transshipment centre existed at Balkh. Indian pilgrims traveling the Silk Road introduced Buddhism to China during the early centuries AD, and Buddhist Gandhāra art flourished during this period. The world's largest Buddha figures (175 feet 【53 metres】 and 120 feet 【about 40 metres】 tall) were carved into a cliff at Bamiyan in the central mountains of Afghanistan during the 4th and 5th centuries AD; the statues were destroyed in 2001 by the country's ruling Taliban. Further evidence of the trade and cultural achievement of the period has been recovered at the Kushān summer capital of Bagrām, north of Kabul; it includes painted glass from Alexandria; plaster matrices, bronzes, porphyries, and alabasters from Rome; carved ivories from India; and lacquers from China. A massive Kushān city at Delbarjin, north of Balkh, and a major gold hoard of superb artistry near Sheberghān, west of Balkh, also have been excavated.

The Kushāns were patrons of the arts and of religion. A major branch of the Silk Road—which carried luxury goods and facilitated the exchange of ideas between Rome, India, and China—passed through Afghanistan, where a transshipment centre existed at Balkh. Indian pilgrims traveling the Silk Road introduced Buddhism to China during the early centuries AD, and Buddhist Gandhāra art flourished during this period. The world's largest Buddha figures (175 feet 【53 metres】 and 120 feet 【about 40 metres】 tall) were carved into a cliff at Bamiyan in the central mountains of Afghanistan during the 4th and 5th centuries AD; the statues were destroyed in 2001 by the country's ruling Taliban. Further evidence of the trade and cultural achievement of the period has been recovered at the Kushān summer capital of Bagrām, north of Kabul; it includes painted glass from Alexandria; plaster matrices, bronzes, porphyries, and alabasters from Rome; carved ivories from India; and lacquers from China. A massive Kushān city at Delbarjin, north of Balkh, and a major gold hoard of superb artistry near Sheberghān, west of Balkh, also have been excavated.The Sāsānids and Hephthalites

The Kushān empire did not long survive Kaniṣka, though for centuries Kushān princes continued to rule in various provinces. Persian Sāsānids (Sāsānian dynasty) established control over parts of Afghanistan, including Bagrām, in AD 241. In 400 a new wave of Central Asian nomads under the Hephthalites (Hephthalite) took control, only to be defeated in 565 by a coalition of Sāsānids and Western Turks. From the 5th through the 7th century many Chinese Buddhist pilgrims continued to travel through Afghanistan. The pilgrim Xüanzang (Xuanzang) wrote an important account of his travels, and several of the religious centres he visited, including Hadda, Ghazna (Ghaznī), Kondoz, Bamiyan, Shotorak, and Bagrām, have been excavated.

The 7th–18th centuries

Under the Hephthalites and Sāsānids, many of the Afghan princedoms were influenced by Hinduism. The Hindu kings of the Shāhī family (Shāhi Family) were concentrated in the Kabul and Ghaznī areas. Excavated sites of the period include a major Hindu Shāhī temple north of Kabul and a chapel in Ghaznī that contains both Buddhist and Hindu statuary, indicating that there was a mingling of these two religions.

The first Muslim dynasties

Islamic (Islāmic world) armies defeated the Sāsānids in 642 at the Battle of Nahāvand (Nahāvand, Battle of) (near modern Hamadān, Iran) and advanced into the Afghan area, but they were unable to hold the territory; cities submitted, only to rise in revolt, and the hastily converted returned to their old beliefs once the armies had passed. The 9th and 10th centuries witnessed the rise of numerous local Islamic dynasties. One of the earliest was the Ṭāhirids (Ṭāhirid Dynasty) of Khorāsān, whose kingdom included Balkh and Herāt; they established virtual independence from the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in 820. The Ṭāhirids were succeeded in 867–869 by a native dynasty from Sīstān, the Ṣaffārids (Ṣaffārid Dynasty). Local princes in the north soon became feudatories of the powerful Sāmānids, who ruled from Bukhara. From 872 to 999 Bukhara, Samarkand, and Balkh enjoyed a golden age under Sāmānid rule.