tropical cyclone

meteorology

Introduction

also called typhoon or hurricane

an intense circular storm that originates over warm tropical oceans and is characterized by low atmospheric pressure, high winds, and heavy rain. Drawing energy from the sea surface and maintaining its strength as long as it remains over warm water, a tropical cyclone generates winds that exceed 119 km (74 miles) per hour. In extreme cases winds may exceed 240 km (150 miles) per hour, and gusts may surpass 320 km (200 miles) per hour. Accompanying these strong winds are torrential rains and a devastating phenomenon known as the storm surge, an elevation of the sea surface that can reach 6 metres (20 feet) above normal levels. Such a combination of high winds and water makes cyclones a serious hazard for coastal areas in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Every year during the late summer months (July–September in the Northern Hemisphere and January–March in the Southern Hemisphere), cyclones strike regions as far apart as the Gulf Coast of North America, northwestern Australia, and eastern India and Bangladesh.

an intense circular storm that originates over warm tropical oceans and is characterized by low atmospheric pressure, high winds, and heavy rain. Drawing energy from the sea surface and maintaining its strength as long as it remains over warm water, a tropical cyclone generates winds that exceed 119 km (74 miles) per hour. In extreme cases winds may exceed 240 km (150 miles) per hour, and gusts may surpass 320 km (200 miles) per hour. Accompanying these strong winds are torrential rains and a devastating phenomenon known as the storm surge, an elevation of the sea surface that can reach 6 metres (20 feet) above normal levels. Such a combination of high winds and water makes cyclones a serious hazard for coastal areas in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Every year during the late summer months (July–September in the Northern Hemisphere and January–March in the Southern Hemisphere), cyclones strike regions as far apart as the Gulf Coast of North America, northwestern Australia, and eastern India and Bangladesh.Tropical cyclones are known by various names in different parts of the world. In the North Atlantic Ocean and the eastern North Pacific they are called hurricanes, and in the western North Pacific around the Philippines, Japan, and China the storms are referred to as typhoons. In the western South Pacific and Indian Ocean they are variously referred to as severe tropical cyclones, tropical cyclones, or simply cyclones. All these different names refer to the same type of storm.

Anatomy of a cyclone

Tropical cyclones are compact, circular storms, generally some 320 km (200 miles) in diameter, whose winds swirl around a central region of low atmospheric pressure. The winds are driven by this low-pressure core and by the rotation of the Earth, which deflects the path of the wind through a phenomenon known as the Coriolis force. As a result, tropical cyclones rotate in a counterclockwise (or cyclonic) direction in the Northern Hemisphere and in a clockwise (or anticyclonic) direction in the Southern Hemisphere.

Tropical cyclones are compact, circular storms, generally some 320 km (200 miles) in diameter, whose winds swirl around a central region of low atmospheric pressure. The winds are driven by this low-pressure core and by the rotation of the Earth, which deflects the path of the wind through a phenomenon known as the Coriolis force. As a result, tropical cyclones rotate in a counterclockwise (or cyclonic) direction in the Northern Hemisphere and in a clockwise (or anticyclonic) direction in the Southern Hemisphere. The wind field of a tropical cyclone may be divided into three regions, as shown in the diagram-->

The wind field of a tropical cyclone may be divided into three regions, as shown in the diagram--> . First is a ring-shaped outer region, typically having an outer radius of about 160 km (100 miles) and an inner radius of about 30 to 50 km (20 to 30 miles). In this region the winds increase uniformly in speed toward the centre. Wind speeds attain their maximum value at the second region, the eyewall, which is typically 15 to 30 km (10 to 20 miles) from the centre of the storm. The eyewall in turn surrounds the interior region, called the eye, where wind speeds decrease rapidly and the air is often calm. These main structural regions are described in greater detail below.

. First is a ring-shaped outer region, typically having an outer radius of about 160 km (100 miles) and an inner radius of about 30 to 50 km (20 to 30 miles). In this region the winds increase uniformly in speed toward the centre. Wind speeds attain their maximum value at the second region, the eyewall, which is typically 15 to 30 km (10 to 20 miles) from the centre of the storm. The eyewall in turn surrounds the interior region, called the eye, where wind speeds decrease rapidly and the air is often calm. These main structural regions are described in greater detail below.The eye

A characteristic feature of tropical cyclones is the eye, a central region of clear skies, warm temperatures, and low atmospheric pressure. Typically, atmospheric pressure at the surface of the Earth is about 1,000 millibars. At the centre of a tropical cyclone, however, it is typically around 960 millibars, and in a very intense “supertyphoon” of the western Pacific it may be as low as 880 millibars. In addition to low pressure at the centre, there is also a rapid variation of pressure across the storm, with most of the variation occurring near the centre. This rapid variation results in a large pressure gradient force, which is responsible for the strong winds present in the eyewall (described below).

Horizontal winds within the eye, on the other hand, are light. In addition, there is a weak sinking motion, or subsidence, as air is pulled into the eyewall at the surface (see the diagram-->

Horizontal winds within the eye, on the other hand, are light. In addition, there is a weak sinking motion, or subsidence, as air is pulled into the eyewall at the surface (see the diagram--> ). As the air subsides, it compresses slightly and warms, so that temperatures at the centre of a tropical cyclone are some 5.5 °C (10 °F) higher than in other regions of the storm. Because warmer air can hold more moisture before condensation occurs, the eye of the cyclone is generally free of clouds. Reports of the air inside the eye being “oppressive” or “sultry” are most likely a psychological response to the rapid change from high winds and rain in the eyewall to calm conditions in the eye.

). As the air subsides, it compresses slightly and warms, so that temperatures at the centre of a tropical cyclone are some 5.5 °C (10 °F) higher than in other regions of the storm. Because warmer air can hold more moisture before condensation occurs, the eye of the cyclone is generally free of clouds. Reports of the air inside the eye being “oppressive” or “sultry” are most likely a psychological response to the rapid change from high winds and rain in the eyewall to calm conditions in the eye.The eyewall

The most dangerous and destructive part of a tropical cyclone is the eyewall. Here winds are strongest, rainfall is heaviest, and deep convective clouds rise from close to the Earth's surface to a height of 15,000 metres (49,000 feet). As noted above, the high winds are driven by rapid changes in atmospheric pressure near the eye, which creates a large pressure gradient force. Winds actually reach their greatest speed at an altitude of about 300 metres (1,000 feet) above the surface. Closer to the surface they are slowed by friction, and higher than 300 metres they are weakened by a slackening of the horizontal pressure gradient force. This slackening is related to the temperature structure of the storm. Air is warmer in the core of a tropical cyclone, and this higher temperature causes atmospheric pressure in the centre to decrease at a slower rate with height than occurs in the surrounding atmosphere. The lessened contrast in atmospheric pressure with altitude causes the horizontal pressure gradient to weaken with height, which in turn results in a decrease in wind speed.

Friction at the surface, in addition to lowering wind speeds, causes the wind to turn inward toward the area of lowest pressure, as shown in the diagram-->

Friction at the surface, in addition to lowering wind speeds, causes the wind to turn inward toward the area of lowest pressure, as shown in the diagram--> . Air flowing into the low-pressure eye cools by expansion and in turn extracts heat and water vapour from the sea surface. Areas of maximum heating have the strongest updrafts, and the eyewall exhibits the greatest vertical wind speeds in the storm—up to 5 to 10 metres (16.5 to 33 feet) per second, or 18 to 36 km (11 to 22 miles) per hour. While such velocities are much less than those of the horizontal winds, updrafts are vital to the existence of the towering convective clouds embedded in the eyewall. Much of the heavy rainfall associated with tropical cyclones comes from these clouds.

. Air flowing into the low-pressure eye cools by expansion and in turn extracts heat and water vapour from the sea surface. Areas of maximum heating have the strongest updrafts, and the eyewall exhibits the greatest vertical wind speeds in the storm—up to 5 to 10 metres (16.5 to 33 feet) per second, or 18 to 36 km (11 to 22 miles) per hour. While such velocities are much less than those of the horizontal winds, updrafts are vital to the existence of the towering convective clouds embedded in the eyewall. Much of the heavy rainfall associated with tropical cyclones comes from these clouds.The upward movement of air in the eyewall also causes the eye to be wider aloft than at the surface. As the air spirals upward it conserves its angular momentum, which depends on the distance from the centre of the cyclone and on the wind speed around the centre. Since the wind speed decreases with height, the air must move farther from the centre of the storm as it rises.

When updrafts reach the stable tropopause (the upper boundary of the troposphere, some 16 km 【10 miles】 above the surface), the air flows outward. The Coriolis force deflects this outward flow, creating a broad anticyclonic circulation aloft. Therefore, horizontal circulation in the upper levels of a tropical cyclone is opposite to that near the surface.

Rainbands

In addition to deep convective cells (compact regions of vertical air movement) surrounding the eye, there are often secondary cells arranged in bands around the centre. These bands, commonly called rainbands, spiral into the centre of the storm. Both the primary cloud band associated with the eyewall and the outer rainbands can be seen in the diagram-->

In addition to deep convective cells (compact regions of vertical air movement) surrounding the eye, there are often secondary cells arranged in bands around the centre. These bands, commonly called rainbands, spiral into the centre of the storm. Both the primary cloud band associated with the eyewall and the outer rainbands can be seen in the diagram--> . In some cases the rainbands are stationary relative to the centre of the moving storm, and in other cases they seem to rotate around the centre. The rotating cloud bands often are associated with an apparent wobbling of the storm track. If this happens as the tropical cyclone approaches a coastline, there may be large differences between the forecast landfall positions and actual landfall.

. In some cases the rainbands are stationary relative to the centre of the moving storm, and in other cases they seem to rotate around the centre. The rotating cloud bands often are associated with an apparent wobbling of the storm track. If this happens as the tropical cyclone approaches a coastline, there may be large differences between the forecast landfall positions and actual landfall.As a tropical cyclone makes landfall, surface friction increases, which in turn increases the convergence of airflow into the eyewall and the vertical motion of air occurring there. The increased convergence and rising of moisture-laden air is responsible for the torrential rains associated with tropical cyclones, which may be in excess of 250 mm (10 inches) in a 24-hour period. At times a storm may stall, allowing heavy rains to persist over an area for several days. In extreme cases, rainfall totals of 760 mm (30 inches) in a five-day period have been reported.

Life of a cyclone

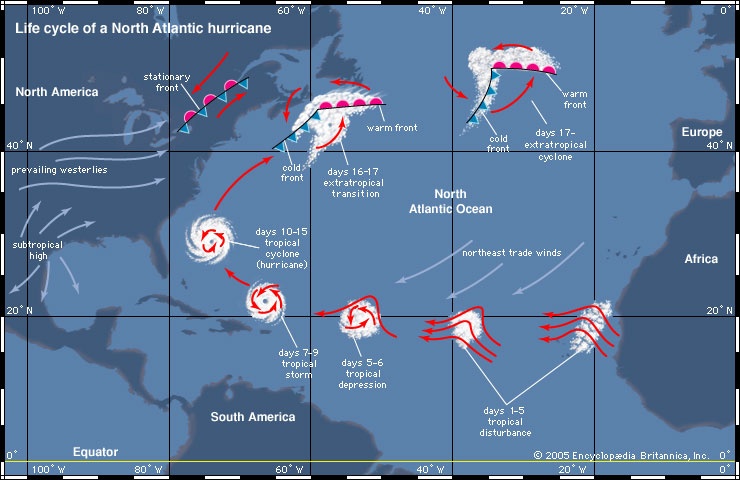

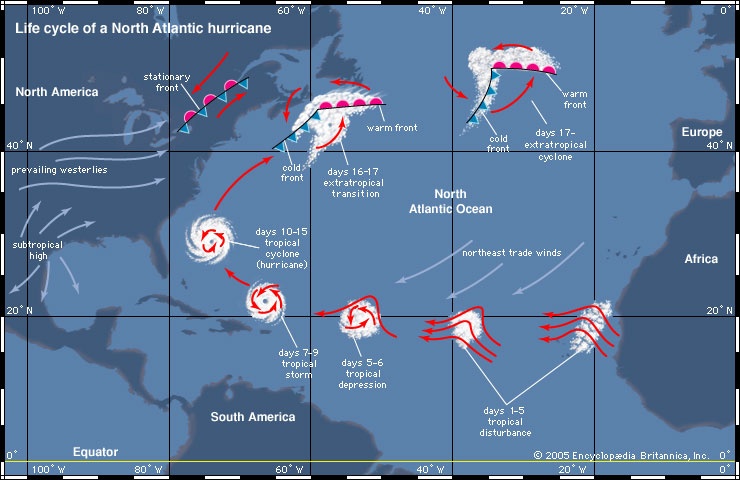

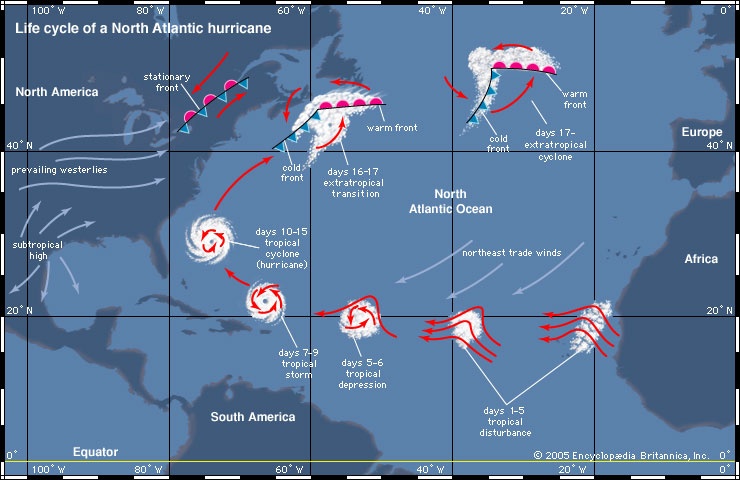

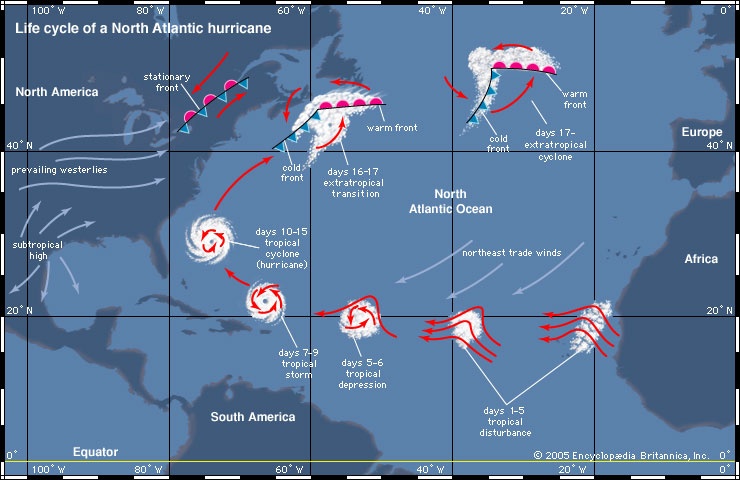

A circulation system goes through a sequence of stages as it intensifies into a mature tropical cyclone, as is shown in the map-->

A circulation system goes through a sequence of stages as it intensifies into a mature tropical cyclone, as is shown in the map--> . The storm begins as a tropical disturbance, which typically occurs when loosely organized cumulonimbus clouds in an easterly wave begin to show signs of a weak circulation. Once the wind speed increases to 36 km (23 miles) per hour, the storm is classified as a tropical depression. If the circulation continues to intensify and the wind speeds exceed 63 km (39 miles) per hour, then the system is called a tropical storm. Once the maximum wind speed exceeds 119 km (74 miles) per hour, the storm is classified as a tropical cyclone.

. The storm begins as a tropical disturbance, which typically occurs when loosely organized cumulonimbus clouds in an easterly wave begin to show signs of a weak circulation. Once the wind speed increases to 36 km (23 miles) per hour, the storm is classified as a tropical depression. If the circulation continues to intensify and the wind speeds exceed 63 km (39 miles) per hour, then the system is called a tropical storm. Once the maximum wind speed exceeds 119 km (74 miles) per hour, the storm is classified as a tropical cyclone.There are six conditions favourable for this process to take place. The conditions are listed first below, and then their dynamics are described in greater detail:

● The temperature of the surface layer of ocean water must be 26.5 °C (80 °F) or warmer, and this warm layer must be at least 50 metres (150 feet) deep.

● A preexisting atmospheric circulation must be located near the surface warm layer.

● The atmosphere must cool quickly enough with height to support the formation of deep convective clouds.

● The middle atmosphere must be relatively humid at a height of about 5,000 metres (16,000 feet) above the surface.

● The developing system must be at least 500 km (300 miles) away from the Equator.

● The wind speed must change slowly with height through the troposphere—no more than 10 metres (33 feet) per second between the surface and an altitude of about 10,000 metres (33,000 feet).

Formation

The fuel for a tropical cyclone is provided by a transfer of water vapour and heat from the warm ocean to the overlying air, primarily by evaporation from the sea surface. As the warm, moist air rises, it expands and cools, quickly becoming saturated and releasing latent heat through the condensation of water vapour. The column of air in the core of the developing disturbance is warmed and moistened by this process. The temperature difference between the warm, rising air and the cooler environment causes the rising air to become buoyant, further enhancing its upward movement.

If the sea surface is too cool, there will not be enough heat available, and the evaporation rates will be too low to provide the tropical cyclone enough fuel. Energy supplies will also be cut off if the warm surface water layer is not deep enough, because the developing tropical system will modify the underlying ocean. Rain falling from the deep convective clouds will cool the sea surface, and the strong winds in the centre of the storm will create turbulence. If the resulting mixing brings cool water from below the surface layer to the surface, the fuel supply for the tropical system will be removed.

The vertical motion of warm air is by itself inadequate to initiate the formation of a tropical system. However, if the warm, moist air flows into a preexisting atmospheric disturbance, further development will occur. As the rising air warms the core of the disturbance by both release of latent heat and direct heat transfer from the sea surface, the atmospheric pressure in the centre of the disturbance becomes lower. The decreasing pressure causes the surface winds to increase, which in turn increases the vapour and heat transfer and contributes to further rising of air. The warming of the core and the increased surface winds thus reinforce each other in a positive feedback mechanism.

Intensification

The dynamics of a tropical cyclone rely on the exterior of a storm being cooler than its core, so it is necessary that the temperature of the atmosphere drop sufficiently rapidly with height. The warm, saturated air rising in the centre of the circulation tends to keep rising as long as the surrounding air is cooler and heavier. This vertical movement allows deep convective clouds to develop. The rising air in the core also draws in some air from the surrounding atmosphere at altitudes of around 5,000 metres (16,000 feet). If this external air is relatively humid, the circulation will continue to intensify. If it is sufficiently dry, then it may evaporate some of the water drops in the rising column, causing the air to become cooler than the surrounding air. This cooling will result in the formation of strong downdrafts that will disrupt the rising motion and inhibit development.

For the development of the rapid rotation characteristic of tropical cyclones, the low-pressure centre must be located at least 500 km (300 miles) away from the Equator. If the initial disturbance is too close to the Equator, then the effect of the Coriolis force will be too small to provide the necessary spin. The Coriolis force deflects the air that is being drawn into the surface low-pressure centre, setting up a cyclonic rotation. In the Northern Hemisphere the direction of the resulting circulation around the low is counterclockwise, and in the Southern Hemisphere it is clockwise.

A final requirement for the intensification of tropical cyclones is that there must be little change in the wind speed with height above the surface. If the winds increase too much with altitude, the core of the system will no longer be vertically aligned over the warm surface that provides its energy. The area being warmed and the surface low-pressure centre will move apart, and the positive feedback mechanism described above will be suppressed. Conditions in the tropics that encourage the development of tropical cyclones include a typically minor north-to-south variation in temperature. This relative lack of a temperature gradient causes wind speed to remain relatively constant with height.

Dissipation

Tropical cyclones dissipate when they can no longer extract sufficient energy from warm ocean water. As mentioned above, a tropical cyclone can contribute to its own demise by stirring up deeper, cooler ocean waters. In addition, a storm that moves over land will abruptly lose its fuel source and quickly lose intensity.

A tropical cyclone that remains over the ocean and moves into higher latitudes will change its structure and become extratropical (extratropical cyclone) as it encounters cooler water, as is shown in the map-->

A tropical cyclone that remains over the ocean and moves into higher latitudes will change its structure and become extratropical (extratropical cyclone) as it encounters cooler water, as is shown in the map--> . The transformation from a tropical to an extratropical cyclone is marked by an increase in the storm's diameter and by a change in shape from circular to comma- or v-shaped as its rainbands reorganize. An extratropical cyclone typically has a higher central pressure and consequently has lower wind speeds. Extratropical cyclones, which are fueled by a north-to-south variation of temperature, weaken and dissipate in a few days.

. The transformation from a tropical to an extratropical cyclone is marked by an increase in the storm's diameter and by a change in shape from circular to comma- or v-shaped as its rainbands reorganize. An extratropical cyclone typically has a higher central pressure and consequently has lower wind speeds. Extratropical cyclones, which are fueled by a north-to-south variation of temperature, weaken and dissipate in a few days.Tropical cyclone damage

Horizontal wind

High winds cause some of the most dramatic and damaging effects associated with tropical cyclones. In the most intense tropical cyclones, sustained winds may be as high as 240 km (150 miles) per hour, and gusts can exceed 320 km (200 miles) per hour. The length of time that a given location is exposed to extreme winds depends on the size of the storm and the speed at which it is moving. During a direct hit from a tropical cyclone, an area may endure high winds for several hours. In that time even the most solidly constructed buildings may begin to suffer damage. The force of the wind increases rapidly with its speed. Sustained winds of 100 km (62 miles) per hour exert a pressure of 718 pascals (15 pounds per square foot), while an approximate doubling of wind speed to 200 km (124 miles) per hour increases the pressure almost fivefold to 3,734 pascals. A building with a large surface area facing the wind may be subjected to immense forces. Some of the local variability in damage that is often observed during tropical cyclones is due to the direction that buildings face relative to the prevailing wind.

Horizontal winds associated with a tropical cyclone vary in strength depending on the area of the storm in which they occur. The strongest winds are located in the right-forward quadrant of the storm, as measured along the line that the storm is moving. The intensification of winds in this quadrant is due to the additive effect of winds from the atmospheric flow in which the storm is embedded. For example, in a hurricane approaching the East Coast of the United States, the highest and most damaging winds are located to the northeast of the storm centre.

Tornadoes (tornado)

The intense sustained winds present near the centre of tropical cyclones are responsible for inflicting heavy damage, but there is another wind hazard associated with these storms— tornadoes. Most tropical disturbances that reach storm intensity have tornadoes associated with them when they make landfall, though the tornadoes tend to be weaker than those observed in the Midwestern United States. The number of tornadoes varies, but about 75 percent of tropical cyclones generate fewer than 10. The largest number of tornadoes associated with a tropical cyclone was 141, reported in 1967 as Hurricane Beulah struck the Texas Gulf Coast in the United States.

Tornadoes can occur in any location near the centre of the storm. At distances greater than 50 km (30 miles) from the centre, they are confined to the northeast quadrant of Northern Hemisphere storms and to the southwest quadrant of Southern Hemisphere storms. How the tornadoes are generated is not clear, but surface friction probably plays a role by causing the wind to slow as the tropical cyclone makes landfall. Wind speeds near the surface decrease while those at higher levels are less affected, setting up a low-level horizontal rotation that becomes tilted into the vertical by updrafts, thus providing the concentrated spin required for a tornado.

Gusts, downbursts, and swirls

In addition to tornadoes, tropical cyclones generate other localized damaging winds. When a tropical cyclone makes landfall, surface friction decreases wind speed but increases turbulence; this allows fast-moving air aloft to be transported down to the surface, thereby increasing the strength of wind gusts. There is also evidence of tropical cyclone downbursts, driven by evaporative cooling of air. These downbursts are similar to microbursts that may occur during severe thunderstorms. The winds associated with them typically flow in a different direction than those of the cyclone, allowing them to be identified. Other small-scale wind features associated with tropical cyclones are swirls. These are very small, intense, and short-lived vortices that occur under convective towers embedded in the eyewall. They are not classified as tornadoes because their peak winds last only a few seconds. Swirls may rotate in either a counterclockwise or a clockwise direction, and their peak winds are estimated to approach 320 km (200 miles) per hour.

The storm surge

In coastal regions an elevation of sea level—the storm surge—is often the deadliest phenomenon associated with tropical cyclones. A storm surge accompanying an intense tropical cyclone can be as high as 6 metres (20 feet). Most of the surge is caused by friction between the strong winds in the storm's eyewall and the ocean surface, which piles water up in the direction that the wind is blowing. For tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere this effect is largest in the right-forward quadrant of the storm because the winds are strongest there. In the Southern Hemisphere the left-forward quadrant has the largest storm surge.

A small part of the total storm surge is due to the change in atmospheric pressure across the tropical cyclone. The higher atmospheric pressure at the edges of the storm causes the ocean surface to bulge under the eye, where the pressure is lowest. However, the magnitude of this pressure-induced surge is minimal because the density of water is large compared with that of air. A pressure drop of 100 millibars across the diameter of the storm causes the sea surface under the eye to rise about 1 metre (3 feet).

Flooding (flood) caused by the storm surge is responsible for most of the deaths associated with tropical cyclone landfalls. Extreme examples of storm surge fatalities include 6,000 deaths in Galveston, Texas, in 1900 and the loss of more than 300,000 lives in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1970 from a storm surge that was estimated to be 9 metres (30 feet) high. Improvements in forecasting the expected height of storm surges and the issuing of warnings are necessary as the population of coastal areas continues to increase.

Rainfall (precipitation)

Tropical cyclones typically bring large amounts of water into the areas they affect. Much of the water is due to rainfall associated with the deep convective clouds of the eyewall and with the rainbands of the outer edges of the storm. Rainfall rates are typically on the order of several centimetres per hour with shorter bursts of much higher rates. It is not uncommon for totals of 500 to 1,000 mm (20 to 40 inches) of rain to be reported over some regions. Rainfall rates such as these may overwhelm the capacity of storm drains, resulting in local flooding. Flooding may be particularly severe in low-lying regions such as in Bangladesh and the Gulf Coast of the United States. It is also a problem in areas where mountains and canyons concentrate the rainfall, as occurred in 1998 when floods caused by rains from Hurricane Mitch washed away entire towns in Honduras.

Tropical cyclones typically bring large amounts of water into the areas they affect. Much of the water is due to rainfall associated with the deep convective clouds of the eyewall and with the rainbands of the outer edges of the storm. Rainfall rates are typically on the order of several centimetres per hour with shorter bursts of much higher rates. It is not uncommon for totals of 500 to 1,000 mm (20 to 40 inches) of rain to be reported over some regions. Rainfall rates such as these may overwhelm the capacity of storm drains, resulting in local flooding. Flooding may be particularly severe in low-lying regions such as in Bangladesh and the Gulf Coast of the United States. It is also a problem in areas where mountains and canyons concentrate the rainfall, as occurred in 1998 when floods caused by rains from Hurricane Mitch washed away entire towns in Honduras.Another source of high precipitation may be provided by the migration of moist air from the clouds of the mature tropical cyclone. When this moisture moves into areas of low pressure at higher latitudes, significant precipitation may result. An example of this occurred in 1983, when the remnants of the eastern Pacific Hurricane Octave moved into a Pacific cold front that had stalled over the southwestern United States, drenching the Arizona desert with 200 mm (8 inches) of rain in a three-day period. On average, that region receives 280 mm (11 inches) of rain in an entire year.

Ranking and naming a cyclone

Intensity scales

atmosphere saffir-simpson Australian scale of cyclone intensityA wide range of wind speeds is possible between tropical cyclones of minimal strength and the most intense ones on record, and tropical cyclones can cause damage ranging from the breaking of tree limbs to the destruction of mobile homes and small buildings. To aid in issuing warnings to areas that may be affected by a storm, and to indicate the severity of the potential threat, numerical rating systems have been developed based on a storm's maximum wind speed and potential storm surge. For tropical systems in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale is used (see the table (atmosphere saffir-simpson)). This scale ranks storms that already have reached hurricane strength. A similar scale used to categorize storms near Australia includes both tropical storms and tropical cyclones (see the table (Australian scale of cyclone intensity)). Though these two scales have different starting points, the most intense rating in each—category 5—is similar. Numerical ranking scales are not utilized in any of the other ocean basins.

Naming systems

It is not uncommon for more than one tropical cyclonic system to be present in a given ocean basin at any given time. To aid forecasters in identifying the systems and issuing warnings, tropical disturbances are given numbers. When a system intensifies to tropical storm strength, it is given a name.

Hurricane names for the North Atlantic Ocean Hurricane names for the eastern North Pacific OceanIn the United States, names given to hurricanes during World War II corresponded to radio code names for the letters of the alphabet (such as Able, Baker, and Charlie). In 1953 the U.S. National Weather Service began to identify hurricanes by female names, and in 1978 a series of alternating male and female names came into use. The lists of names are recycled every six years—that is, the 2003 list is used again in 2009, the 2004 list in 2010, and so on—as is shown in the table (Hurricane names for the North Atlantic Ocean) of tropical cyclone names for the North Atlantic and the table (Hurricane names for the eastern North Pacific Ocean) of names for the eastern North Pacific. Names of very intense, damaging, or otherwise newsworthy storms are retired. Names that will not be used again include Gilbert, a 1988 category 5 hurricane that had the lowest central atmospheric pressure (888 millibars) ever recorded in the Atlantic. Also retired is Mitch (Mitch, Hurricane), the name of a category 5 hurricane that stalled off the coast of Honduras for two days in 1998 before slowly moving inland, inundating Central America with heavy rain and causing mudslides and floods that took nearly 10,000 lives. Another notable storm whose name has been retired was Hurricane Ivan, which reached category 5 on three separate occasions during its long life cycle in September 2004. Ivan almost completely destroyed all agricultural infrastructure in Grenada, wrecked much of that year's crops in Jamaica, leveled 1.1 million hectares (2.7 million acres) of timber in Alabama, and caused almost 100 deaths along its path.

atmosphere w n pacificPacific and Indian basin storms are named according to systems established by regional committees under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization. Each region maintains its own list of names, and changes to the list (such as retiring a name) are ratified at formal meetings. Two or more lists of names are alternated each year for several regions, including the central North Pacific (i.e., the Hawaii region), the western North Pacific and South China Sea (see the table (atmosphere w n pacific)), the southern Indian Ocean west of 90° E, the western South Pacific Ocean, and Australia's eastern, central, and northern ocean regions. In some areas, such as the northern Indian Ocean, tropical cyclones are given numbers instead of names.

Location and patterns of tropical cyclones

ocean basins and peak seasons

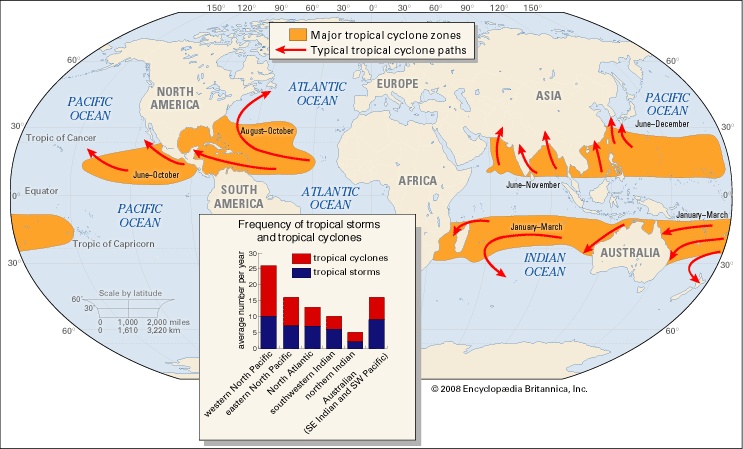

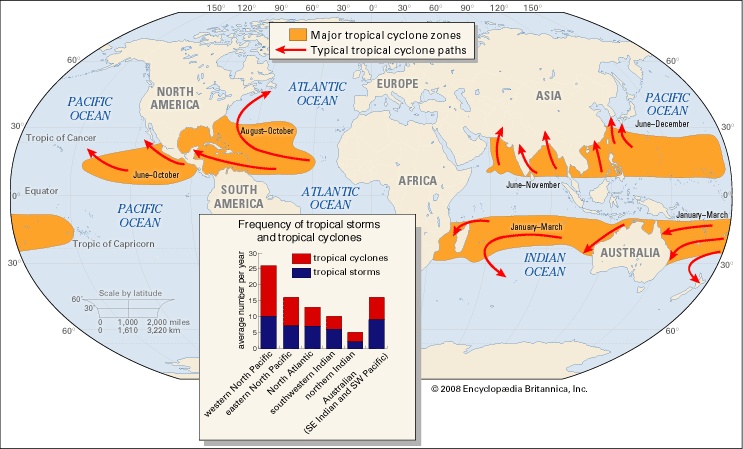

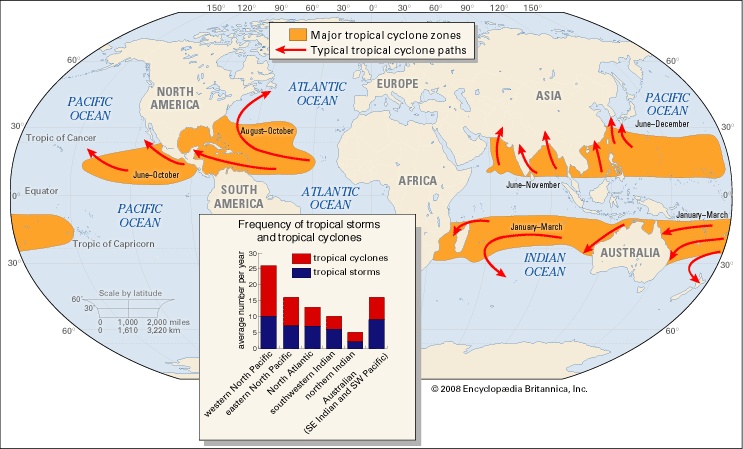

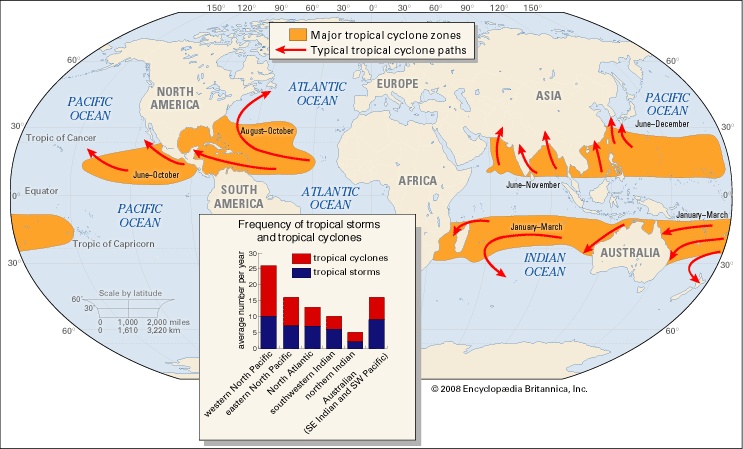

Tropical oceans spawn approximately 80 tropical storms annually, and about two-thirds are severe (category 1 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson scale of intensity). Almost 90 percent of these storms form within 20° north or south of the Equator. Poleward of those latitudes, sea surface temperatures are too cool to allow tropical cyclones to form, and mature storms moving that far north or south will begin to dissipate. Only two tropical ocean basins do not support tropical cyclones, because they lack waters that are sufficiently warm. The Peru Current in the eastern South Pacific and the Benguela Current in the South Atlantic carry cool water Equatorward from higher latitudes and so deter tropical cyclone development. The Pacific Ocean generates the greatest number of tropical storms and cyclones, as can be seen in the map-->

Tropical oceans spawn approximately 80 tropical storms annually, and about two-thirds are severe (category 1 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson scale of intensity). Almost 90 percent of these storms form within 20° north or south of the Equator. Poleward of those latitudes, sea surface temperatures are too cool to allow tropical cyclones to form, and mature storms moving that far north or south will begin to dissipate. Only two tropical ocean basins do not support tropical cyclones, because they lack waters that are sufficiently warm. The Peru Current in the eastern South Pacific and the Benguela Current in the South Atlantic carry cool water Equatorward from higher latitudes and so deter tropical cyclone development. The Pacific Ocean generates the greatest number of tropical storms and cyclones, as can be seen in the map--> . The most powerful storms, sometimes called supertyphoons, occur in the western Pacific. The Indian Ocean is second in the total number of storms, and the Atlantic Ocean ranks third.

. The most powerful storms, sometimes called supertyphoons, occur in the western Pacific. The Indian Ocean is second in the total number of storms, and the Atlantic Ocean ranks third.Tropical cyclones are warm season phenomena. The peak frequency of these storms occurs after the maximum in solar radiation is received for the year, which occurs on June 22 in the Northern Hemisphere and December 22 in the Southern Hemisphere. The ocean surface reaches its maximum temperature several weeks after the solar radiation maximum, so most tropical cyclones occur during the late summer to early fall—that is, from July to September in the Northern Hemisphere and from January to March in the Southern Hemisphere.

Favourable wind systems

The lower latitudes are favourable for the generation of tropical cyclones not only because of their warm ocean waters but also because of the general atmospheric circulation of the region. Tropical cyclones originate from loosely organized, large-scale circulation systems such as those associated with the strong, low-level easterly jet over Africa. This jet generates easterly waves—regions of low atmospheric pressure that have a maximum intensity at an altitude of about 3,600 metres (12,000 feet) and a horizontal extent of about 2,400 km (1,500 miles). Most of the tropical cyclones in the Atlantic and eastern North Pacific begin as easterly waves. Given favourable conditions, an easterly wave may intensify and contract horizontally, ultimately resulting in the characteristic circulation of a tropical cyclone. In the western Pacific, large areas of upper-level low pressure help pull air from the centre of the developing disturbances and thus contribute to a drop in surface atmospheric pressure. It is these features, known as tropical upper tropospheric troughs, or TUTTs, that are responsible for the large number of tropical cyclones in the western Pacific.

In some cases, external geographic factors aid in development of tropical cyclones. The mountains of Mexico and Central America modify easterly waves that move through the Caribbean and into the eastern Pacific. This often results in closed circulations at low levels over the eastern Pacific Ocean, many of which develop into tropical cyclones.

Tropical cyclone tracks

Tropical cyclones in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres tend to move westward and drift slowly poleward, as shown in the map-->

Tropical cyclones in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres tend to move westward and drift slowly poleward, as shown in the map--> . Their motion is due in large part to the general circulation of the Earth's atmosphere. Surface winds in the tropics, known as the trade winds, blow from east to west, and they are responsible for the general westward motion of tropical cyclones. For the poleward movement, two other factors are responsible. One is the presence of large-scale regions of subsiding air, known as subtropical highs, over the oceans poleward of the trade winds. These regions of high atmospheric pressure have anticyclonic circulations (that is, clockwise circulation in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern), so that winds on the western edges of these large-scale circulations move toward the poles. The second factor is the Coriolis force, which becomes progressively stronger at higher latitudes. The diameter of a tropical cyclone is large enough for the Coriolis force to influence its poleward side more strongly, and hence the tropical cyclone is deflected toward the pole. Once a tropical cyclone moves poleward of the subtropical high, it begins to move eastward under the influence of the middle-latitude westerlies (which blow toward the east). When the motion of a tropical cyclone changes from westward to eastward, the tropical cyclone is said to recurve.

. Their motion is due in large part to the general circulation of the Earth's atmosphere. Surface winds in the tropics, known as the trade winds, blow from east to west, and they are responsible for the general westward motion of tropical cyclones. For the poleward movement, two other factors are responsible. One is the presence of large-scale regions of subsiding air, known as subtropical highs, over the oceans poleward of the trade winds. These regions of high atmospheric pressure have anticyclonic circulations (that is, clockwise circulation in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern), so that winds on the western edges of these large-scale circulations move toward the poles. The second factor is the Coriolis force, which becomes progressively stronger at higher latitudes. The diameter of a tropical cyclone is large enough for the Coriolis force to influence its poleward side more strongly, and hence the tropical cyclone is deflected toward the pole. Once a tropical cyclone moves poleward of the subtropical high, it begins to move eastward under the influence of the middle-latitude westerlies (which blow toward the east). When the motion of a tropical cyclone changes from westward to eastward, the tropical cyclone is said to recurve.Tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere can travel to higher latitudes than in the Southern Hemisphere because of the presence of warm clockwise oceanic currents such as the Kuroshio and the Gulf Stream. In the North Atlantic the warm waters of the Gulf Stream supply energy to hurricanes as they move along the east coast of the United States, allowing them to survive for a longer time. It is not uncommon for very intense tropical systems to make landfall as far north as Boston (42° Ν). On the other hand, hurricanes do not make landfall on the west coast of the United States even though prevailing winds over the North Pacific Ocean move eastward toward land. Instead, they tend to weaken rapidly as they recurve because they are moving over cooler ocean waters.

Tracking and forecasting (weather forecasting)

In the first half of the 20th century the identification of tropical cyclones was based on changes in weather conditions, the state of the sea surface, and reports from areas that had already been affected by the storm. This method left little time for advance warning and contributed to high death tolls. Observation networks and techniques improved with time; with the advent of weather satellites (weather satellite) in the 1960s, the early detection and tracking of tropical cyclones was greatly improved.

Use of satellites and aircraft

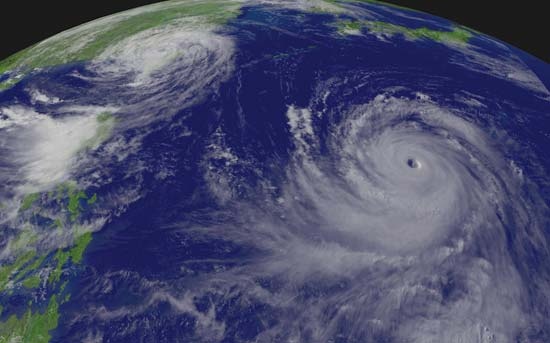

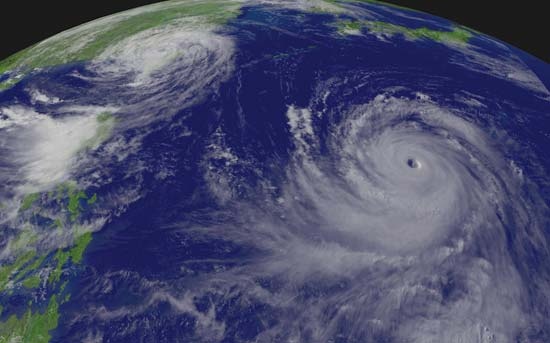

An array of geostationary satellites (those that remain over a fixed position on the Earth) is operated by a number of countries. Each of these satellites provides continuous displays of the Earth's surface in visible light (see the photograph-->

An array of geostationary satellites (those that remain over a fixed position on the Earth) is operated by a number of countries. Each of these satellites provides continuous displays of the Earth's surface in visible light (see the photograph--> ) and in infrared wavelengths. It is the latter that are most important in tracking the stages of tropical cyclone development. Infrared images show the temperatures of cloud tops, thus allowing the loosely organized convection associated with easterly waves to be detected by the presence of cold, high clouds. They also show the deep, organized convection characteristic of a tropical cyclone. Satellite images not only show a storm's location but also can be used to estimate its intensity because certain cloud patterns are characteristic of particular wind speeds.

) and in infrared wavelengths. It is the latter that are most important in tracking the stages of tropical cyclone development. Infrared images show the temperatures of cloud tops, thus allowing the loosely organized convection associated with easterly waves to be detected by the presence of cold, high clouds. They also show the deep, organized convection characteristic of a tropical cyclone. Satellite images not only show a storm's location but also can be used to estimate its intensity because certain cloud patterns are characteristic of particular wind speeds.Although satellite images provide general information on the location and intensity of tropical cyclones, detailed information on a storm's strength and structure must be obtained directly, using aircraft. This information is essential in providing the most accurate warnings possible. Operational reconnaissance is done only by the United States for storms that may affect its continental landmass. No other country does this type of reconnaissance. Tropical cyclones in other ocean basins occur over a larger region, and most countries do not have the financial resources to maintain research aircraft. When evidence of a developing circulation is detected in the Atlantic or Caribbean, a U.S. Air Force C-130 aircraft is dispatched to determine if a closed circulation is present. The centre of circulation is noted, and an instrument called a dropsonde is released through the bottom of the aircraft to measure the temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, and wind speed. In many cases, the naming of a tropical storm, or its upgrade from tropical storm to tropical cyclone, is based on aircraft observations.

Landfall forecasts

Tropical storms developing in the world's ocean basins are tracked by various national weather services that have been designated Regional Specialized Meteorological Centres (RSMCs) by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The RSMCs are located at Miami, Florida, and Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.; Tokyo, Japan; Nadi, Fiji; Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia; New Delhi, India; and Saint-Denis, Réunion. Warnings are also issued for more limited regions by Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres in a number of locations, including Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; Wellington, New Zealand; and Perth, Western Australia, and Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. In addition, the Joint Typhoon Warning Centers in Hawaii are responsible for U.S. military forecasts in the western Pacific and Indian Oceans, which overlap a number of WMO regions of responsibility.

Forecasting hurricane landfall and providing warnings for storms that will effect the United States is done by the National Hurricane Center in Miami. Forecasters use a variety of observational information from satellites and aircraft to determine the current location and intensity of the storm. This information is used along with computer forecast models to predict the future path and intensity of the storm. There are three basic types of computer models. The simplest ones use statistical relations based on the typical paths of hurricanes in a region, along with the assumption that the current observed motion of the storm will persist. A second type of model, called a statistical-dynamical model, forecasts the large-scale circulation by solving equations that describe changes in atmospheric pressure, wind, and moisture. Statistical relations that predict the track of the storm based on the large-scale conditions are then used to forecast the storm's future position. A third type of model is a purely dynamic forecast model. In this model, equations are solved that describe changes in both the large-scale circulation and the tropical cyclone itself. Dynamic forecast models show the interaction of the tropical cyclone with its environment, but they require the use of large and powerful computers as well as very complete descriptions of the structure of the tropical cyclone and that of the surrounding environment. Computer models currently do well in forecasting the path of tropical cyclones, but they are not as reliable in forecasting changes in intensity more than 24 hours in advance.

Once forecasters have determined that a tropical cyclone is likely to make landfall, warnings are issued for the areas that may be affected. The forecasters provide a “best-track” forecast, which is an estimate of the track and maximum wind speed over a period of 72 hours based on all available observations and computer model results. Strike probability forecasts are issued that indicate probabilities (in percentages) that the tropical cyclone will affect a given area over a given time interval. These forecasts allow local authorities to begin warning and evacuation plans. As the storm approaches, a tropical cyclone watch is issued for areas that may be threatened. In especially vulnerable areas, evacuation may be initiated based on the watch. If tropical cyclone conditions are expected in an area within 24 hours, a tropical cyclone warning is issued. Once a warning is issued, evacuation is recommended for areas prone to storm surges and areas that may be isolated by high water.

Long-term forecasts

Forecasts of expected numbers of Atlantic tropical cyclones are now being made well in advance of the start of each year's tropical cyclone season. The forecast model takes into account seasonal trends in factors related to tropical cyclone formation such as the presence of El Niño or La Niña oceanic conditions (see the section below), amount of rainfall over Africa, winds in the lower stratosphere, and atmospheric pressure and wind tendencies over the Caribbean. Based on these factors, forecasts are issued concerning the expected numbers of tropical storms, tropical cyclones, and intense tropical cyclones for the Atlantic. These forecasts are issued in December, and they are revised in June and again in August of each year for the current Atlantic tropical cyclone season. The forecast model has displayed reasonable skill in predicting the total number of storms each season.

Climatic variations and tropical cyclone frequency

The number of tropical cyclones generated during a given a year has been observed to vary with certain climatic conditions that modify the general circulation of the atmosphere. One of these conditions is the intermittent occurrence of El Niño, an oceanic phenomenon characterized by the presence every few years of unusually warm water over the equatorial eastern Pacific. The presence of unusually cool surface waters in the region is known as La Niña. While the factors connecting El Niño and La Niña to tropical cyclones are complicated, there are a few general relationships. During years when El Niño conditions are present, upper-level winds over the Atlantic tend to be stronger than normal, which increases the vertical shear and decreases tropical cyclone activity. La Niña conditions result in weaker shear and enhanced tropical cyclone activity. The variation of sea surface temperature associated with El Niño and La Niña also changes the strength and location of the jet stream, which in turn alters the tracks of tropical cyclones. There are indications that El Niño and La Niña modulate tropical cyclone activity in other parts of the world as well. More tropical cyclones seem to occur in the eastern portion of the South Pacific during El Niño years, and fewer occur during La Niña years.

The possibility is being examined that changes in the Earth's climate might alter the numbers, intensity, or paths of tropical cyclones worldwide. Increasing the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere through the burning of fossil fuels and other human activities may increase the global average temperature—and the temperature of the sea surface. These potential changes would influence the maximum intensity reached by a tropical cyclone, which depends on both the sea surface temperature and the temperature of the upper troposphere. An increase in global temperature, however, could actually decrease the number of tropical cyclones because any change in temperature would be accompanied by changes in the Earth's general circulation. If tropical atmospheric circulation were to change in such a way as to increase the winds at upper levels, then there could be a decrease in tropical cyclone activity. An assessment by the World Meteorological Organization of the effect of climate change on tropical cyclones concluded that there is no evidence to suggest that an enhanced greenhouse effect will cause any major changes in the global location of tropical cyclone genesis or the total area of the Earth's surface over which tropical cyclones form. Furthermore, while the maximum potential intensity of tropical cyclones may increase by 10 to 20 percent with a doubling of the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, factors such as increased cooling due to ocean spray and changes in the vertical temperature variation may offset these effects.

Additional Reading

A general overview of the physical mechanisms of tropical cyclone formation and behaviour, with particular emphasis on Hurricane Andrew of 1992, is presented by Roger A. Pielke, Sr., and Roger A. Pielke, Jr., Hurricanes: Their Nature and Impacts on Society (1997). For a comprehensive survey of tropical cyclones, including threat assessment and prediction, see Robert H. Simpson and Herbert Riehl, The Hurricane and Its Impact (1981). John M. Williams and Iver W. Duedall, Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms (1997), discusses tropical storms and cyclones affecting Florida since 1871. A classic work on the structure and mechanics of tropical cyclones is Gordon E. Dunn and Banner I. Miller, Atlantic Hurricanes, rev. ed. (1964). C. Donald Ahrens, Meteorology Today, 6th ed. (1999), is an introductory textbook containing a chapter on tropical cyclones.The formation and tracking of Hurricane Gilbert is recorded in Hurricane! (1989), a video documentary produced for the American Public Broadcasting Service's NOVA series. Hurricanes (1998), produced for the History Channel's Wrath of God series, provides footage of three great cyclones that struck the United States in the 20th century.A technically advanced discussion of all aspects of tropical cyclones is given by Gary R. Foley, Hugh E. Willoughby, John L. McBride, Russell L. Elsberry, Isaac Ginis, and L. Chien, Global Perspectives on Tropical Cyclones, published by World Meteorological Organization (1995). Also at an advanced level, the factors controlling variability of Atlantic hurricanes, seasonal and long-term forecasts, and the impact of hurricanes on the insurance industry is presented by James B. Elsner and A. Birol Kara, Hurricanes of the North Atlantic: Climate and Society (1999).

- Michael Ovitz

- Michael Pacher

- Michael Phelps

- Michael Powell

- Michael Praetorius

- Michael Psellus

- Michael Ramsey, Baron Ramsey Of Canterbury

- Michael Riffaterre

- Michael Riley Galitzen

- Michael R. Milken

- Michael Rumaker

- Michael S. Brown

- Michael Scot

- Michael S. Dukakis

- Michael Servetus

- Michael S. Harper

- Michaels, Leonard

- Michael Smith

- Michael Somes

- Michael Spinks

- Michael Thomas Sadler

- Michael Thonet

- Michael Todd

- Michael V Calaphates

- Michael Ventris