Evans, Walker

American photographer

Introduction

born November 3, 1903, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.

died April 10, 1975, New Haven, Connecticut

American photographer whose influence on the evolution of ambitious photography (photography, history of) during the second half of the 20th century was perhaps greater than that of any other figure. He rejected the prevailing, highly aestheticized view of artistic photography, of which Alfred Stieglitz (Stieglitz, Alfred) was the most visible proponent, and constructed instead an artistic strategy based on the poetic resonance of common but exemplary facts, clearly described. His most characteristic pictures show quotidian American life during the second quarter of the century, especially through the description of its vernacular architecture, its outdoor advertising, the beginnings of its automobile culture, and its domestic interiors.

Early life and work

Evans spent much of his childhood in the Chicago suburb of Kenilworth, before moving several times and attending a series of secondary schools that culminated at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachussetts. His academic record was spotty at best, and it did not improve at Williams College, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, which he left after only one year.

After leaving college, Evans spent three years in New York City working at dead-end jobs. In 1926 his father, an advertising executive, offered to finance the continuation of his education in Paris, and so Evans spent a year in France, where he audited classes at the Sorbonne and tried to write (with very limited success). On his return to New York in the spring of 1927, Evans lived the life of a writer in Greenwich Village—albeit a writer with writer's block and no significant publication record. Although he had made some casual snapshots in France, his serious interest in photography seems to have developed, at first tentatively, during this period.

In 1928 and 1929 Evans made a substantial number of photographs that unmistakably indicate artistic ambition. Most of these depict semiabstract patterns derived from skyscrapers or other machine-age products. However, in the fall of 1929 he became interested in the work of the French photographer Eugène Atget (Atget, Eugène), who eschewed deliberately artistic effects in his simple, economic photographs of Paris and its environs at the turn of the 20th century. The photographer Berenice Abbott (Abbott, Berenice), the most dedicated supporter of Atget's work, had acquired his residual estate of prints and plates and brought the collection to New York. Evans's friend James Stern remembered—almost half a century later—that he and Evans had gone to Abbott's apartment to see Atget's work, perhaps for the first time in America. Stern said that in Evans he had caught the glimpse of an obsession, causing him to ask, “Surely it is not invidious to ask what kind of Evans we would have, which way his art would have developed, had there never been an Atget?”

Near the end of his life, Evans would say that seeing Atget confirmed a new direction that was in fact already taking place in his work, and there is no reason to challenge this formulation. Nevertheless, it would seem that during the early 1930s Evans virtually worked his way through the Atget catalog, applying its lessons to the very different raw material offered by his own country. Evans's unswerving commitment to a direct and unsentimental style, free of dramatic vantage points and romantic glints and shadows, was a commitment to an art that concealed its art. On the level of style, his work might have been mistaken for that of a skilled if literal-minded commercial photographer. Evans's idea of artistic style was expressed by Gustave Flaubert (Flaubert, Gustave)'s maxim that an artist should be “like God in Creation…he should be everywhere felt, but nowhere seen.”

The Farm Security Administration

During the early 1930s Evans had worked only occasionally (and skeptically) as a professional photographer, preferring to live precariously from occasional assignments, often from friends. The idea that he should be asked to make a photograph conceived by someone else was offensive to his ego; in addition, there were many sorts of photographs that he had never learned to make. However, from mid-1935 to early 1937 Evans worked for a regular salary as a member of the so-called “historical unit” of the Farm Security Administration (FSA; earlier, the Resettlement Administration), an agency of the Department of Agriculture. Its assignment was to provide a photographic survey of rural America, primarily in the South. To the degree that the function of the unit was ever defined, its goal was less history than a form of political persuasion. In any case it afforded Evans the means of traveling, generally alone and without immediate financial concerns, in search of the material for his art.

During the early 1930s Evans had worked only occasionally (and skeptically) as a professional photographer, preferring to live precariously from occasional assignments, often from friends. The idea that he should be asked to make a photograph conceived by someone else was offensive to his ego; in addition, there were many sorts of photographs that he had never learned to make. However, from mid-1935 to early 1937 Evans worked for a regular salary as a member of the so-called “historical unit” of the Farm Security Administration (FSA; earlier, the Resettlement Administration), an agency of the Department of Agriculture. Its assignment was to provide a photographic survey of rural America, primarily in the South. To the degree that the function of the unit was ever defined, its goal was less history than a form of political persuasion. In any case it afforded Evans the means of traveling, generally alone and without immediate financial concerns, in search of the material for his art. In a working life of almost half a century, one might guess that half of Evans's best work was done during that year and a half, when he constructed with photographs an analogue of rural life in America. What made Evans's work new was the kind of facts that he selected for scrutiny, and the subtlety of his appreciation of those facts and their resonant allusions. Most of Evans's best work dealt not with people but with the things they made: he was concerned most of all with the character of American culture as it was expressed in its vernacular architecture and in its unofficial decorative arts, such as billboards and shop windows. His subjects were on the surface resolutely prosaic and artless, yet it can be argued that what he demanded of them was quality—he demanded that they be exemplary of the brave, groping, sometimes comic effort to create a built culture that would be consonant with an unprecedented nation.

In a working life of almost half a century, one might guess that half of Evans's best work was done during that year and a half, when he constructed with photographs an analogue of rural life in America. What made Evans's work new was the kind of facts that he selected for scrutiny, and the subtlety of his appreciation of those facts and their resonant allusions. Most of Evans's best work dealt not with people but with the things they made: he was concerned most of all with the character of American culture as it was expressed in its vernacular architecture and in its unofficial decorative arts, such as billboards and shop windows. His subjects were on the surface resolutely prosaic and artless, yet it can be argued that what he demanded of them was quality—he demanded that they be exemplary of the brave, groping, sometimes comic effort to create a built culture that would be consonant with an unprecedented nation.In 1938 the Museum of Modern Art (Modern Art, Museum of) in New York City published American Photographs to accompany a retrospective exhibition of Evans's work to that time. The book's 87 pictures were made between 1929 and 1936 and selected by Evans. It is remarkable that more than a third of the pictures were made during the brief but astonishingly productive 18 months when Evans was employed by the FSA. American Photographs, with a critical essay by Lincoln Kirstein (Kirstein, Lincoln), remains perhaps the most influential photography book of the modern era.

During the late summer of 1936 Evans was on leave from the FSA to work for Fortune magazine with writer James Agee (Agee, James) on a study of three sharecropping families from Hale county, Alabama. The project never appeared in Fortune, but it was finally published in 1941 as the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, surely one of the oddest and most challenging books that have attempted to make sense of the combination of words and photographs. The solution of Evans and Agee—good friends and mutual admirers of each other's work—was to not collaborate at all, except in an additive sense. Agee wrote his text, full of High Church extravagance, which was prefaced by a portfolio of 31 unlabeled photographs—bound together at the front of the book—by Evans. These photographs are as reticent and Puritan in style as could be imagined, capturing every aspect of the three families—their houses, their rooms, their furniture, their land. In 1960, after Agee's death, Evans prepared a new edition with twice as many photographs, a change that did not essentially alter the nature of the book.

During the late summer of 1936 Evans was on leave from the FSA to work for Fortune magazine with writer James Agee (Agee, James) on a study of three sharecropping families from Hale county, Alabama. The project never appeared in Fortune, but it was finally published in 1941 as the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, surely one of the oddest and most challenging books that have attempted to make sense of the combination of words and photographs. The solution of Evans and Agee—good friends and mutual admirers of each other's work—was to not collaborate at all, except in an additive sense. Agee wrote his text, full of High Church extravagance, which was prefaced by a portfolio of 31 unlabeled photographs—bound together at the front of the book—by Evans. These photographs are as reticent and Puritan in style as could be imagined, capturing every aspect of the three families—their houses, their rooms, their furniture, their land. In 1960, after Agee's death, Evans prepared a new edition with twice as many photographs, a change that did not essentially alter the nature of the book.In contrast to the aggressive intrusiveness that even in the 1930s characterized much photographic reportage, Evans's pictures from this project exhibit an almost courtly reticence to intrude into the most private aspects of his subjects' lives. And yet, in spite of the absence of vulgar prying, the viewer thinks he knows the so-called Ricketts, Woods, and Gudgers better than any star in the tabloids, perhaps partly because they seem collaborators in the design of their portraits. Perhaps Evans understood that the meagre thinness of the sharecroppers' lives was rendered most clearly when they had dressed themselves up in their Sunday best.

Later life and work

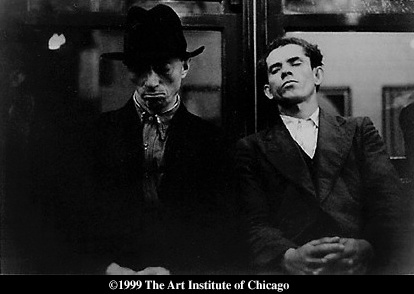

In 1943 Evans was hired by Time, Inc., and he spent the next 22 years with that publishing empire, most of them with the business magazine Fortune, with whom he developed a relationship as a photographer and writer that involved a comfortable salary, substantial independence, and little heavy lifting. He continued to photograph architecture, especially rural churches, and he also began a series of revealing, spontaneous photographs of people taken in the New York City subways; the series was eventually published in book form as Many Are Called in 1966. In 1965 he began teaching in the School of Art and Architecture of Yale University, and in the following year he retired from Time, Inc.

In 1943 Evans was hired by Time, Inc., and he spent the next 22 years with that publishing empire, most of them with the business magazine Fortune, with whom he developed a relationship as a photographer and writer that involved a comfortable salary, substantial independence, and little heavy lifting. He continued to photograph architecture, especially rural churches, and he also began a series of revealing, spontaneous photographs of people taken in the New York City subways; the series was eventually published in book form as Many Are Called in 1966. In 1965 he began teaching in the School of Art and Architecture of Yale University, and in the following year he retired from Time, Inc.During the 1940 and '50s—the heyday of photojournalism in the magazines—Evans, with his prickly, superior intelligence and jealously guarded independence, was not a useful role model for most working photographers. Yet, as the promise of the magazines began to lose its lustre, Evans increasingly became a hero to younger photographers who were not comfortable as part of an editorial team. Robert Frank (Frank, Robert), Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus (Arbus, Diane), and Lee Friedlander are among the most significant later photographers who have acknowledged their debt to Evans. His influence on artists in fields other than photography has also been great.

Additional Reading

The critical literature on Evans is unusually rich, although the biographical sources on the artist are less satisfactory. In addition to those mentioned in the text, works of note include John Szarkowski, Walker Evans (1971), published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; Jerry L. Thompson (ed.), Walker Evans at Work (1982, reissued 1994), a very useful examination of the way a photographer thinks; Jeff L. Rosenheim and Douglas Eklund, Unclassified: A Walker Evans Anthology: Selections from the Walker Evans Archive, Department of Photographs, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2000), with an introduction by Maria Morris Hambourg; Peter Galassi, Walker Evans and Company (2000), a study of Evans's artistic ideas and how they influenced later artists; and Leo Rubinfien, “The Poetry of Plain Seeing,” in Art in America, 88(12):74–85, 132–135 (December 2000).

- François-Louis de Bourbon, prince de Conti

- François-Louis Rousselet Château-Renault, marquis de

- François-Louis Rousselet, marquis de Château-Renault

- François Magendie

- François Mansart

- François-Marie, 1st Duke de Broglie

- François-Marie Broglie, 1st Duke de

- François-Marie Raoult

- François Marius Granet

- François, marquis de Barbé-Marbois

- François Mauriac

- François Maynard

- François-Michel Le Tellier Louvois, marquis de

- François-Michel Le Tellier, marquis de Louvois

- François Mignet

- François Mitterrand

- François Montmorency, Duke de

- François-Noël Babeuf

- François Pienaar

- François Quesnay

- François Rabelais

- François-René-Auguste Mallarmé

- François Rude

- François, Seigneur De La Bigotiere Viète

- François Stephanus Malan