United Arab Emirates

Introduction

United Arab Emirates, flag of the federation of seven emirates along the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula.

federation of seven emirates along the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula.

federation of seven emirates along the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula.

federation of seven emirates along the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula. The largest of these emirates, Abū Ẓaby (Abu Dhabi), which comprises more than three-fourths of the federation's total land area, is the centre of its oil industry and borders Saudi Arabia on the federation's southern and eastern borders. The port city of Dubai, located at the base of the mountainous Musandam Peninsula, is the capital of the emirate of Dubayy (Dubai) and is one of the region's most vital commercial and financial centres, housing hundreds of multinational corporations in a forest of skyscrapers. The smaller emirates of Al-Shāriqah (Shāriqah, Al-) (Sharjah), Ajmānʿ, Umm al-Qaywayn, and Raʾs al-Khaymah also occupy the peninsula, whose protrusion north toward Iran forms the Strait of Hormuz (Hormuz, Strait of) linking the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman (Oman, Gulf of). The federation's seventh member, Al-Fujayrah (Fujayrah, Al-), faces the Gulf of Oman and is the only member of the union with no frontage along the Persian Gulf.

The largest of these emirates, Abū Ẓaby (Abu Dhabi), which comprises more than three-fourths of the federation's total land area, is the centre of its oil industry and borders Saudi Arabia on the federation's southern and eastern borders. The port city of Dubai, located at the base of the mountainous Musandam Peninsula, is the capital of the emirate of Dubayy (Dubai) and is one of the region's most vital commercial and financial centres, housing hundreds of multinational corporations in a forest of skyscrapers. The smaller emirates of Al-Shāriqah (Shāriqah, Al-) (Sharjah), Ajmānʿ, Umm al-Qaywayn, and Raʾs al-Khaymah also occupy the peninsula, whose protrusion north toward Iran forms the Strait of Hormuz (Hormuz, Strait of) linking the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman (Oman, Gulf of). The federation's seventh member, Al-Fujayrah (Fujayrah, Al-), faces the Gulf of Oman and is the only member of the union with no frontage along the Persian Gulf. Historically the domain of individual Arab clans and families, the region now comprising the emirates also has been influenced by Persian culture owing to its close proximity to Iran, and its porous maritime borders have for centuries invited migrants and traders from elsewhere. In the 18th century, Portugal and The Netherlands extended their holdings in the region but retreated with the growth of British naval power there; following a series of truces with Britain in the 19th century, the emirates united to form the Trucial States (also called Trucial Oman or the Trucial Sheikhdoms). The states gained autonomy following World War II (1939–45), when the trucial states of Bahrain and Qatar declared independent statehood. The rest were formally united in 1971, with the city of Abu Dhabi serving as the capital. The stability of the federation has since been tested by rivalries between the families governing the larger states of Abū Ẓaby and Dubayy, though external events such as the Persian Gulf War (1990–91) and an ongoing territorial dispute with Iran have served to strengthen the emirates' political cohesion.

Historically the domain of individual Arab clans and families, the region now comprising the emirates also has been influenced by Persian culture owing to its close proximity to Iran, and its porous maritime borders have for centuries invited migrants and traders from elsewhere. In the 18th century, Portugal and The Netherlands extended their holdings in the region but retreated with the growth of British naval power there; following a series of truces with Britain in the 19th century, the emirates united to form the Trucial States (also called Trucial Oman or the Trucial Sheikhdoms). The states gained autonomy following World War II (1939–45), when the trucial states of Bahrain and Qatar declared independent statehood. The rest were formally united in 1971, with the city of Abu Dhabi serving as the capital. The stability of the federation has since been tested by rivalries between the families governing the larger states of Abū Ẓaby and Dubayy, though external events such as the Persian Gulf War (1990–91) and an ongoing territorial dispute with Iran have served to strengthen the emirates' political cohesion.The emirates comprise a mixed environment of rocky desert, coastal plains and wetlands, and waterless mountains. The seashore is a haven for migratory waterfowl and draws birdwatchers from all over the world; the country's unspoiled beaches and opulent resorts also have drawn international travelers. Standing at a historic and geographic crossroads and made up of diverse nationalities and ethnic groups, the United Arab Emirates present a striking blend of ancient customs and modern technology, of cosmopolitanism and insularity, and of wealth and want. The rapid pace of modernization of the emirates prompted travel writer Jonathan Raban to note of the capital: “The condition of Abu Dhabi was so evidently mint that it would not have been surprising to see adhering to the buildings bits of straw and polystyrene from the crates in which they had been packed.”

Land (United Arab Emirates)

The United Arab Emirates is bordered by Qatar to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west and south, and Oman to the east and northeast. It is slightly smaller in area than Portugal. Since the early 1990s the emirates have been in a dispute with Iran over the ownership of three islands: Abū Mūsā and Greater and Lesser Tunb (Ṭunb al-Kubrā and Ṭunb al-Ṣughrā). In addition, the border with Saudi Arabia has never been defined, which was not an issue until Saudi Arabia began production at the Shaybah oil field in the border region in 1998.

The United Arab Emirates is bordered by Qatar to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west and south, and Oman to the east and northeast. It is slightly smaller in area than Portugal. Since the early 1990s the emirates have been in a dispute with Iran over the ownership of three islands: Abū Mūsā and Greater and Lesser Tunb (Ṭunb al-Kubrā and Ṭunb al-Ṣughrā). In addition, the border with Saudi Arabia has never been defined, which was not an issue until Saudi Arabia began production at the Shaybah oil field in the border region in 1998.Relief

Nearly the entire country is desert, containing broad areas of sand. Some of the world's largest sand dunes are located east of ʿArādah in the oases of Al-Liwāʾ. Important oases are at Al-ʿAyn (Ayn, Al-ʿ) about 100 miles (160 km) east of Abu Dhabi. Along the eastern portion of the Musandam Peninsula, the northern extension of the Ḥajar Mountains (Ḥajar, al-) (also shared by Oman) offers the only other major relief feature; elevations rise to about 6,500 feet (2,000 metres) at their highest point. The Persian Gulf coast is broken by shoals and dotted with islands that offer shelter to small vessels. There are, however, no natural deepwater harbours; both Dubayy's Port Rāshid and the gigantic Port Jabal ʿAlī, 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Dubai city, are man-made, as are major ports in Abū Ẓaby, Al-Shāriqah, and Raʾs al-Khaymah. The coast of the Gulf of Oman (Oman, Gulf of) is more regular and has three natural harbours— Dibā, Khawr Fakkān, and Kalbā.

Drainage

The United Arab Emirates has no perennial streams nor any regularly occurring bodies of surface water. Precipitation, what little falls, is drained from the mountains in the form of seasonal wadis that terminate in inland salt flats, or sabkhahs, whose drainage is frequently blocked by the country's constantly shifting dunes. In the far west the Maṭṭī Salt Flat extends southward into Saudi Arabia, and coastal sabkhahs, which are occasionally inundated by the waters of the Persian Gulf, lie in the areas around Abu Dhabi.

Climate

The climate is hot and humid along the coast and is hotter still, but dry, in the interior. Rainfall averages only 4 to 6 inches (100 to 150 mm) annually, though it fluctuates considerably from year to year. The average January temperature is 64 °F (18 °C), while in July the temperature averages 91 °F (33 °C). Summertime highs can reach 115 °F (46 °C) on the coast and 120 °F (49 °C) or more in the desert. In midwinter and early summer, winds known as the shamāl (shamal) (Arabic: “norther”) blow from the north and northwest, bearing dust and sand.

Plant and animal life

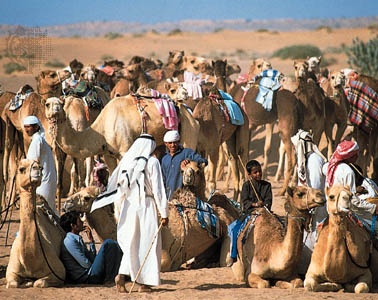

Because of the desert climate, vegetation is scanty and largely limited to the low shrubs that offer forage to nomadic herds; but millions of trees, notably mangroves (mangrove), have been planted in Abū Ẓaby and have provided habitats for various species. In the oases, date palms are raised together with alfalfa (lucerne). Fruits are grown, and the Al-ʿAyn oases east of Abu Dhabi are known for their mangoes. Animal life includes domesticated goats, sheep, and camels, together with cattle and poultry, which were introduced in more recent times. Wildlife consists of predators such as the caracal, sand cat (Felis margarita), and the Ruppell's (Vulpes ruppelli) and red foxes; larger animals such as the Arabian oryx and Arabian and Persian gazelles; smaller mammals such as the cape hare, lesser jerboa, and various types of gerbil; and a variety of snakes and lizards. The gulf waters harbour schools of mackerel, grouper, tuna, and porgies, as well as sharks and occasional whales. In the 1990s the government initiated a conservation and management program to preserve and protect desert animal and plant life.

Because of the desert climate, vegetation is scanty and largely limited to the low shrubs that offer forage to nomadic herds; but millions of trees, notably mangroves (mangrove), have been planted in Abū Ẓaby and have provided habitats for various species. In the oases, date palms are raised together with alfalfa (lucerne). Fruits are grown, and the Al-ʿAyn oases east of Abu Dhabi are known for their mangoes. Animal life includes domesticated goats, sheep, and camels, together with cattle and poultry, which were introduced in more recent times. Wildlife consists of predators such as the caracal, sand cat (Felis margarita), and the Ruppell's (Vulpes ruppelli) and red foxes; larger animals such as the Arabian oryx and Arabian and Persian gazelles; smaller mammals such as the cape hare, lesser jerboa, and various types of gerbil; and a variety of snakes and lizards. The gulf waters harbour schools of mackerel, grouper, tuna, and porgies, as well as sharks and occasional whales. In the 1990s the government initiated a conservation and management program to preserve and protect desert animal and plant life.People (United Arab Emirates)

Ethnic groups

Only about one-fifth of the emirates' residents are citizens. The remainder are mostly foreign workers and their dependents, with South Asians constituting the largest of these groups. Arabs from countries other than the United Arab Emirates and Iranians account for another significant portion. Southeast Asians, including many Filipinos, have immigrated in increasing numbers to work in various capacities.

Languages and religion

The official language of the United Arab Emirates is Arabic (Arabic language). Modern Standard Arabic is taught in schools, and most native Emiratis speak a dialect of Gulf Arabic that is generally similar to that spoken in surrounding countries. A number of languages are spoken among the expatriate community, including various dialects of Pashto, Hindi, Balochi, and Persian. English is also widely spoken.

About three-fourths of the population is Muslim (Islāmic world), of which roughly four-fifths belong to the Sunni (Sunnite) branch of Islam; Shīʿite minorities exist in Dubayy and Al-Shāriqah. There are also small but growing numbers of Christians and Hindus in the country.

About three-fourths of the population is Muslim (Islāmic world), of which roughly four-fifths belong to the Sunni (Sunnite) branch of Islam; Shīʿite minorities exist in Dubayy and Al-Shāriqah. There are also small but growing numbers of Christians and Hindus in the country.Settlement patterns and demographic trends

The population of the United Arab Emirates is concentrated primarily in cities along both coasts, although the interior oasis settlement of Al-ʿAyn has grown into a major population centre as well. Several emirates have exclaves within other emirates.

The federation's birth rate is one of the lowest among the Persian Gulf states, and the infant mortality rate has decreased substantially. Owing to the large number of foreign workers, more than two-thirds of the population is male. The country's death rate is well below the world average, and the average life expectancy is about 75 years. The major causes of death are cardiovascular disease, accidents and poisonings, and cancer.

Economy

The federation's economy is dominated by the petroleum produced in the Abū Ẓaby and Dubayy emirates. The wealthiest of the emirates, Abū Ẓaby contains nearly one-tenth of the world's proven oil (petroleum) reserves and contributes more than half of the national budget.

Agriculture and fishing

Agricultural production—centred largely in the emirates of Raʾs al-Khaymah and Al-Fujayrah, in the two exclaves of ʿAjmān, and at Al-ʿAyn—has expanded considerably through the increased use of wells and pumps to provide water for irrigation. However, agriculture contributes only a small fraction of gross domestic product (GDP) and employs less than one-tenth of the workforce. Dates are a major crop, as are tomatoes, cucumbers, and eggplants, and the United Arab Emirates is nearly self-sufficient in fruit and vegetable production. The country also produces enough eggs, poultry, fish, and dairy products to meet its own needs but must import most other foodstuffs, notably grains. The Arid Lands Research Centre at Al-ʿAyn experiments with raising crops in a desert environment. Most commercial fishing is concentrated in Umm al-Qaywayn, and the emirates have one of the largest fishing sectors in the Arab world.

Resources and power

Oil was discovered in Abū Ẓaby in 1958, and the government of that emirate owns a controlling interest in all oil-producing companies in the federation through the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). Petroleum production contributes about one-third GDP but employs only a tiny fraction of the workforce. The largest petroleum concessions are held by an ADNOC subsidiary, Abu Dhabi Marine Operating Company (ADMA-OPCO), which is partially owned by British, French, and Japanese interests. One of the main offshore fields is located in Umm al-Shāʾif. Al-Bunduq offshore field is shared with neighbouring Qatar but is operated by ADMA-OPCO. A Japanese consortium operates an offshore rig at Al-Mubarraz, and other offshore concessions are held by American companies. Onshore oil concessions are held by another ADNOC company, the Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operations, which is likewise partially owned by American, French, Japanese, and British interests. Other concessions also are held by Japanese companies.

Petroleum production in Dubayy began in 1969. There are offshore oil fields at Ḥaql Fatḥ, Fallah, and Rāshid. Dubayy owns a controlling interest in all oil produced in the emirate. Al-Shāriqah began producing oil in 1974; another field, predominantly yielding natural gas, was discovered six years later. In 1984 oil production began off the shore of Raʾs al-Khaymah, in the Persian Gulf. Dubayy produces about one-third of the country's total output of petroleum.

The federation's natural gas reserves are among the world's largest, and most fields are found in Abū Ẓaby. In the late 1990s the United Arab Emirates began investing heavily to develop its natural gas sector, both for export and to fire domestic thermal power plants; at the beginning of the 21st century, however, crude petroleum exports continued to far outstrip exports of natural gas.

Manufacturing

The emirates have attempted to diversify their economy to avoid complete dependence on oil, and manufacturing has played a significant part in that effort. A petrochemical industrial complex has been established at Al-Ruways (Ruways, Al-), 140 miles (225 km) southwest of Abu Dhabi city, with a petroleum refinery, a gas fractionation plant, and an ammonia and urea plant. Dubayy's revenues have been invested in projects such as a dry dock and a trade centre; expansion of its airport began in 2002, and additional hotels have been built, including the striking Burj al-ʿArab (Tower of the Arabs), which opened in the late 1990s. Construction on the city's Burj Dubai (“Dubai Tower”) continued in 2007, when the project, then still in progress, became both the world's tallest building and the tallest freestanding structure. Al-Shāriqah has built a cement plant, a plastic-pipe factory, and paint factories. Manufacturing accounts for about one-seventh of GDP and employs a comparable proportion of the workforce.

Finance

The Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates was established in 1980, with Dubayy and Abū Ẓaby each depositing half of their revenues in the institution. The bank also issues the UAE dirham, the emirates' national currency. There are commercial, investment, development, foreign, and domestic banks as well as a bankers' association. In 1991 the worldwide operations of Abū Ẓaby's Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), partly owned by the ruling family, were closed down after corrupt practices were uncovered, and the emirate subsequently created the Abu Dhabi Free Zone Authority to develop a new financial centre. The emirates' first official stock exchange, the Dubai Financial Market (Sūq Dubayy al-Mālī), was opened in 2000, followed by the Dubai International Financial Exchange in 2005.

The Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates was established in 1980, with Dubayy and Abū Ẓaby each depositing half of their revenues in the institution. The bank also issues the UAE dirham, the emirates' national currency. There are commercial, investment, development, foreign, and domestic banks as well as a bankers' association. In 1991 the worldwide operations of Abū Ẓaby's Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), partly owned by the ruling family, were closed down after corrupt practices were uncovered, and the emirate subsequently created the Abu Dhabi Free Zone Authority to develop a new financial centre. The emirates' first official stock exchange, the Dubai Financial Market (Sūq Dubayy al-Mālī), was opened in 2000, followed by the Dubai International Financial Exchange in 2005.Finance is an important component of the emirates' economy, and the country's liberal banking regulations have made it a popular destination for foreign funds, both open and clandestine. Dubai in particular has become a major world banking centre and a hub for unofficial financial institutions known as ḥawālahs (or hundīs), which specialize in transferring money internationally beyond state regulation. While such institutions are used primarily to transfer remittances, they also have been a way for terrorist (terrorism) organizations and criminal groups to move and launder illicit funds.

Trade

Trade has long been important to Dubayy and Al-Shāriqah. Even before the discovery of oil, Dubayy's prosperity was assured by its role as the Persian Gulf's leading entrepôt. (It was known especially as a route for smuggling gold into India.) In 1995 the United Arab Emirates joined the World Trade Organization and since then has developed a number of free-trade zones, technology parks, and modern ports in order to attract trade. The large free-trade zone of Port Jabal ʿAlī was developed during the 1980s and has done much to attract foreign manufacturing industries interested in producing goods for export.

Exports are dominated by petroleum and natural gas. Imports consist primarily of machinery and transport equipment, gold, precious stones and foods. Major trading partners include Japan, western European countries, South Korea, and China. A large amount of trade is in reexports to neighbouring gulf countries.

Services

The service sector, including public administration, defense, tourism, and construction, employs roughly two-fifths of the workforce and accounts for some one-fifth of GDP. Tourism has played an increasing role in the economy since the late 1990s. In order to develop its tourism sector, the government has encouraged hotel, resort, and restaurant construction and airport expansion.

The service sector, including public administration, defense, tourism, and construction, employs roughly two-fifths of the workforce and accounts for some one-fifth of GDP. Tourism has played an increasing role in the economy since the late 1990s. In order to develop its tourism sector, the government has encouraged hotel, resort, and restaurant construction and airport expansion.Labour and taxation

Expatriate workers constitute about nine-tenths of the labour force, and more in some private sector areas. Conditions for these workers often can be harsh, and at the beginning of the 21st century, the state did not allow workers to organize. Like other gulf states that depend heavily on foreign workers, the emirates have attempted to reduce the number of foreign employees—in a program known as Emiratization—by providing incentives for businesses to hire Emirati nationals. There are no personal taxes in the United Arab Emirates, and corporate taxes are only levied on oil companies and foreign banks. The bulk of government revenue is generated from nontax incomes, largely from the sale of petroleum products. In the early 21st century the expatriate labour issue persisted despite landmark developments. New laws were instituted that ban work during the heat of the midday hours in summer and that prohibit the use of children (largely expatriate) as jockeys in camel races. In addition, a number of strikes and protests in 2005 by unpaid expatriate labourers against a major construction and development company were resolved in favour of the workers. Early in 2006, the government announced the drafting of a new law permitting the formation of unions and wage bargaining; later that year, however, it instead passed a law permitting the deportation of striking workers, and worker organization remained illegal.

Expatriate workers constitute about nine-tenths of the labour force, and more in some private sector areas. Conditions for these workers often can be harsh, and at the beginning of the 21st century, the state did not allow workers to organize. Like other gulf states that depend heavily on foreign workers, the emirates have attempted to reduce the number of foreign employees—in a program known as Emiratization—by providing incentives for businesses to hire Emirati nationals. There are no personal taxes in the United Arab Emirates, and corporate taxes are only levied on oil companies and foreign banks. The bulk of government revenue is generated from nontax incomes, largely from the sale of petroleum products. In the early 21st century the expatriate labour issue persisted despite landmark developments. New laws were instituted that ban work during the heat of the midday hours in summer and that prohibit the use of children (largely expatriate) as jockeys in camel races. In addition, a number of strikes and protests in 2005 by unpaid expatriate labourers against a major construction and development company were resolved in favour of the workers. Early in 2006, the government announced the drafting of a new law permitting the formation of unions and wage bargaining; later that year, however, it instead passed a law permitting the deportation of striking workers, and worker organization remained illegal.Transportation and telecommunications

An excellent road system, developed in the late 1960s and '70s, carries motor vehicles throughout the country and links it to its neighbours. The addition of a tunnel to the bridges connecting Dubai city and the nearby commercial centre of Dayrah facilitates the movement of traffic across the small saltwater inlet that separates them. The cities of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Raʾs al-Khaymah, and Al-Fujayrah are served by international airports; a sixth airport at Al-ʿAyn was completed in the mid-1990s. The airport at Dubai is one of the busiest in the Middle East.

An excellent road system, developed in the late 1960s and '70s, carries motor vehicles throughout the country and links it to its neighbours. The addition of a tunnel to the bridges connecting Dubai city and the nearby commercial centre of Dayrah facilitates the movement of traffic across the small saltwater inlet that separates them. The cities of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Raʾs al-Khaymah, and Al-Fujayrah are served by international airports; a sixth airport at Al-ʿAyn was completed in the mid-1990s. The airport at Dubai is one of the busiest in the Middle East.The federation has a number of large and modern ports, including the facilities at Dubayy's Port Rāshid, which is serviced by a vast shipyard, and Port Jabal ʿAlī, situated in one of the largest man-made harbours in the world and one of the busiest ports in the gulf. Of the smaller harbours on the Gulf of Oman, Al-Shāriqah has a modest port north of the city. At the beginning of the 21st century, the country had no rail system; however, a contract was established with a Japanese corporation in 2005 for the construction of light-rail service in the city of Dubai, and a number of additional projects, including monorail service in Abu Dhabi and linkages to the Saudi rail networks, were proposed in the following years.

The state-controlled Emirates Telecommunications Corporation, known as Etisalat (Ittiṣālāt), is a major telecommunications provider in the country. Radio, television, telephone, and cellular telephone service is prevalent and widely used. In 2000 Etisalat began providing Internet service, and the emirates soon had one of the largest subscriber bases per capita in the Middle East. In 2005 a second licensed operator, Emirates Integrated Telecommunications Company (du), began providing telephone and high-speed Internet service, and in 2006 they reached an agreement with Etisalat to link their networks.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

The highest governmental authority is the Supreme Council of Rulers, which is composed of the quasi-hereditary rulers of the seven emirates. The president and vice president of the federation are elected for five-year terms by the Supreme Council from among its members. The president appoints a prime minister and a cabinet. The unicameral legislature, the Federal National Council, is an advisory body made up of 40 members appointed by the individual emirates for two-year terms. A provisional constitution was ratified in 1971 and was made permanent in 1996 by the Supreme Council.

Local government

The United Arab Emirates has a federal system of government, and any powers not assigned to the federal government by the constitution devolve to the constituent emirates. Generally, the distribution of power within the federal system is similar to those in other such systems—for example, the federation government administers foreign policy, determines broad economic policy, and runs the social welfare system—and a significant amount of power is exercised at the individual emirate level, notably in Abū Ẓaby and Dubayy.

Justice

The constitution calls for a legal code based on Sharīʿah (Islamic law). In practice, the judiciary blends Western and Islamic legal principles. At the federal level the judicial branch consists of the Union Supreme Court and several courts of first instance: the former deals with emirate-federal or inter-emirate disputes and crimes against the state, and the latter cover administrative, commercial, and civil disputes between individuals and the federal government. Other legal matters are left to local judicial bodies.

Political process

Until the beginning of the 21st century, there were no political parties in the emirates, and no elections were held. In late 2006 a limited number of participants were permitted to vote in the first-ever elections. An electoral college of about 7,000 (less than 1 percent of the population) was eligible to participate in the selection of half of the membership of the advisory Federal National Council; the other half was to remain designated by appointment. On the whole, leadership in each emirate falls to that emirate's most politically prominent tribe (an agnatic lineage group composed of a number of related families), and the paramount leader, the emir, is selected by the notables of the ruling tribe from among their number—this is usually, but not always, a son of the previous emir. Each tribe, however, has its own leader, or sheikh, and a certain degree of political pluralism is necessary to maintain the ruling family's position. This is largely facilitated by the institution called the majlis, the council meeting. During the majlis the leader hears grievances, mediates disputes, and disperses largesse, and, in theory, anyone under the leader's rule must be granted access to the majlis.

Security

The emirates' defense forces were merged in 1976, but the forces in Dubayy and Abū Ẓaby have retained some independence. The Supreme Council has made the right to raise armed forces a power of the national government. In 2006 the Supreme National Security Council, which included the president, prime minister, and chief of staff of the armed forces, among others, was formed to deal with the emirates' security needs. The number of uniformed military personnel is high for a country the size of the emirates, as is total military spending per capita. Most personnel are in the army, but the emirates maintain a small navy and air force, and a large number of expatriates serve in the military.

Health and welfare

Hospital services are free to nationals, and medical services are concentrated in Dubayy and Abū Ẓaby, which have numerous hospitals, child-welfare clinics, and other health facilities. In the late 1990s the emirates began privatizing health care, which led to a significant rise in the number of hospitals and physicians. Government spending on health care has also increased.

Housing

A considerable proportion of government spending, at both the federal and local levels, is devoted to constructing and financing housing and to developing civil infrastructure such as power, water, and waste removal. The federation government makes housing available to citizens through direct low-interest loans, subsidies on rental units, and grants of housing at no charge, and thousands of Emiratis have taken advantage of these programs.

Education

Education in the emirates is free and mandatory at the primary level for all children from ages 6 to 12. Secondary education is not compulsory. There are a number of fine institutions of higher education in the emirates, and both boys and girls attend public school. Female students far outnumber males at the United Arab Emirates University, which opened at Al-ʿAyn in 1977, and Zayed University (1998) provides women with technical education. At the beginning of the 21st century, more than three-fourths of the population was literate, and the female literacy rate exceeded that for men.

Cultural life

The cultural traditions of the United Arab Emirates are rooted in Islam and resonate with the wider Arab world, especially with the neighbouring states of the Persian Gulf. The federation has experienced the impact of Islamic resurgence, though Islam in the emirates is generally less austere than in Saudi Arabia. Tribal identities in the United Arab Emirates remain fairly strong, despite urbanization and the presence of a large expatriate community, and the family is still considered the strongest and most cohesive social unit.

Daily life and social customs

In several ways, change is apparent in the federation's cultural life. Changes in attitudes toward marriage and the employment of women are discernible. Some women are now given more choice in a marriage partner, and they have gained greater access to education and some types of professional work. New forms of entertainment, ranging from football (soccer) matches to DVD players, have affected taste and behaviour.

Although few Emiratis retain the lifeways of their forebears—practicing a nomadic lifestyle or plying the Persian Gulf in search of fish and pearls—many traditional modes of living continue. The major Islamic holidays, including the two ʿīds (festivals), Īd al-Fiṭrʿ and Īd al-Aḍḥāʿ, are observed among the Muslim majority, and traditional dress is still the norm. For women, traditional attire consists of a light chemise known as a dirʿ, which is often worn beneath a more ornate dress (thawb). Beneath the dress a sirwāl, a type of loose trouser, is worn. Outside the home or in the presence of strangers, women still cover themselves with a dark cloak known as an ʿabāyah and cover their heads with a scarf called a shāl, which may also serve as a veil (ḥijāb or burquʿ). Fabrics are often delicate, colourful, and highly embroidered, and Emirati women wear a variety of fine gold and silver jewelry.

The traditional garb for men consists of a long, simple, ankle-length garment known as a dishdashah (or thawb). Usually made of white cotton, the dishdashah may also be of a heavier material and may be made in a variety of colours. The standard head covering is the ghuṭrah, a light scarf (usually white or white and red checkered, also known as a kaffiyeh) held in place by a black cord of camel hair known as an ʿiqāl. Colour, style, and material of head-wear may vary among groups.

Emirati cuisine reflects the variety of cultural influences that the country has experienced over the centuries. Hummus, fūl (spiced bean paste), falafel, and shāwurmah (shwarma; broiled meat served on flat bread) are dishes standard to the Arab world, whereas the influence of Iranian cuisine can be seen in the Emirati preference for rice as a staple and ingredients such as saffron, cardamom, and rose water as flavouring in desserts. As in all countries of the region, lamb and chicken are the preferred meats, and fresh fruits—including dates, figs, lemons, and limes—vegetables, and unleavened bread (khubz) are daily fare. The preferred drink is coffee, served in the popular fashion—hot, strong, and sweet.

The arts

As is true of other countries of the Arabian Peninsula, traditional arts such as pottery, weaving, and metalworking occupy a prominent place in cultural life. The manufacture of handicrafts is an economic mainstay for smaller villages, providing goods to sell in the souks (open-air markets) that lie at the heart of small towns and large cities alike. Traditional storytelling remains a much-admired art form, and Emirati culture, like Arab culture on the whole, esteems poetry, whether it is classical, contemporary, or the Bedouin vernacular form called nabaṭī. Traditional music, such as the ḥudāʾ—sung originally by caravanners while on the trail—is enjoyed alongside popular music from abroad, and traditional dances such as the ʿayyālah (often called ʿarḍah), a type of sword dance, are performed on special occasions.

The Ministry of Information and Culture sponsors a number of events annually, including plays and music festivals, and helps support the numerous folklore associations in the emirates. The Sharjah Theatre Festival brings together talent from all seven emirates. Annual international book fairs in Sharjah and Abu Dhabi cities are highly regarded, and film festivals in the emirates are gaining in popularity and reputation. The Dubai Air Show has become a major regional event.

Cultural institutions

Dubai Museum is located in al-Fahīdī Fort and features displays on Bedouin life, local history, dances, and musical instruments. The fort is also home to a military museum. Al-ʿAyn is the site of a museum devoted to Bedouin culture and the emirates' pre-oil history. Sharjah city features a noted natural history museum. Dubai city is growing as a centre for regional film, television, and music production.

Sports and recreation

Sports are popular in the United Arab Emirates and are strongly supported by the government. The Ministry of Youth and Sports oversees and encourages the many groups, clubs, and associations that provide sports-related activities. Football (soccer) is the most-watched spectator sport, and horse racing also enjoys widespread popularity. The federation is also a major centre for camel racing, a traditional sport that became increasingly popular late in the 20th century, and for falconry, once an important means of hunting. Dubayy hosts many international sporting events, most notably for golf, tennis, rugby, and boat racing. The country made its Olympic debut at the 1984 Summer Games.

Media and publishing

The news media are concentrated in Abū Ẓaby, Dubayy, and Al-Shāriqah. A number of daily newspapers are published, in both Arabic and English. Radio and television programs are broadcast daily from Abū Ẓaby, Dubayy, Al-Shāriqah, and Raʾs al-Khaymah, in those same languages.

History

This discussion focuses on the United Arab Emirates since the 19th century. For a treatment of earlier periods and of the country in its regional context, see Arabia, history of.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the dominant tribal faction was the Āl Qawāsim (singular: Qāsimī), whose ships controlled the maritime commerce (notably fishing and pearling) concentrated in the lower Persian Gulf and in much of the Indian Ocean. Attacks on British (British Empire) and Indian ships led to a British naval attack in 1819 that defeated the Qāsimī forces, and the British became dominant in the region.

The Āl Qawāsim thus lost power and influence in the region, and the Banū Yās tribal confederation of Abū Ẓaby (Abu Dhabi) became dominant. The Banū Yās were centred on the Al-ʿAyn and Al-Liwāʾ oases of Abū Ẓaby, and their strength was land-based. Under the leadership of the Āl Nahyān (members of the Āl Bū Falāḥ tribe), the Banū Yās have been the most powerful element in the region since the mid-19th century. The principal sheikhs along the coast signed a series of agreements during that century—a general treaty of peace in 1820, the perpetual maritime truce in 1853 (which gave the Trucial Coast its name), and exclusive agreements in 1892 restricting their foreign relations to British discretion—and the sheikhdoms became known as the Trucial States.

A council of the Trucial States began to meet semiannually in 1952 to discuss administrative issues. In January 1968, following the announcement by the British government that its forces would be withdrawn from the Persian Gulf by late 1971, Trucial Oman and the sheikhdoms of Qatar and Bahrain initiated plans to form a confederation. After three years of negotiations, however, Qatar and Bahrain decided to become independent sovereign states, and the former Trucial States, excluding Raʾs al-Khaymah, announced the formation of the United Arab Emirates in December 1971. Raʾs al-Khaymah joined the federation in February 1972.

The struggle for centralization

Abū Ẓaby initiated a movement toward centralization in December 1973, when several of its former cabinet members took positions with the federal government. In May 1976 the seven emirates agreed to merge their armed forces, and in November of that year a provision was added to the constitution that gave the federal government the right to form an army and purchase weapons. Conflicts regarding centralization within the government in 1978 prompted Dubayy and Raʾs al-Khaymah to refuse to submit their forces to federal command, and Dubayy began purchasing weapons independently. A proposal to form a federal budget, merge revenues, and eliminate internal boundaries was rejected by Dubayy and Raʾs al-Khaymah, in spite of strong domestic support. Dubayy ended its opposition, however, when its ruler, Sheikh Rāshid ibn Saʿīd al-Maktūm (Maktūm, Rāshid ibn Saʿīd, Sheikh Āl), was offered the premiership of the federal government; he took office in July 1979. Sheikh Zāyid ibn Sulṭān al-Nahyān (Nahyān, Sheikh Zāyid ibn Sulṭān Āl) of Abū Ẓaby served as president of the United Arab Emirates from 1971 to his death in 2004, when he was succeeded by his son Sheikh Khalifa ibn Zāyid al-Nahyān as ruler of Abū Ẓaby and president of the emirates. Sheikh Rāshid (Maktūm, Rāshid ibn Saʿīd, Sheikh Āl) of Dubayy died in 1990, and his positions as ruler of Dubayy and vice president and prime minister of the United Arab Emirates were assumed, successively, by his sons Sheikh Maktūm ibn Rāshid al-Maktūm (1990–2006) and, since 2006, Sheikh Muhammad ibn Rāshid al-Maktūm.

Abū Ẓaby initiated a movement toward centralization in December 1973, when several of its former cabinet members took positions with the federal government. In May 1976 the seven emirates agreed to merge their armed forces, and in November of that year a provision was added to the constitution that gave the federal government the right to form an army and purchase weapons. Conflicts regarding centralization within the government in 1978 prompted Dubayy and Raʾs al-Khaymah to refuse to submit their forces to federal command, and Dubayy began purchasing weapons independently. A proposal to form a federal budget, merge revenues, and eliminate internal boundaries was rejected by Dubayy and Raʾs al-Khaymah, in spite of strong domestic support. Dubayy ended its opposition, however, when its ruler, Sheikh Rāshid ibn Saʿīd al-Maktūm (Maktūm, Rāshid ibn Saʿīd, Sheikh Āl), was offered the premiership of the federal government; he took office in July 1979. Sheikh Zāyid ibn Sulṭān al-Nahyān (Nahyān, Sheikh Zāyid ibn Sulṭān Āl) of Abū Ẓaby served as president of the United Arab Emirates from 1971 to his death in 2004, when he was succeeded by his son Sheikh Khalifa ibn Zāyid al-Nahyān as ruler of Abū Ẓaby and president of the emirates. Sheikh Rāshid (Maktūm, Rāshid ibn Saʿīd, Sheikh Āl) of Dubayy died in 1990, and his positions as ruler of Dubayy and vice president and prime minister of the United Arab Emirates were assumed, successively, by his sons Sheikh Maktūm ibn Rāshid al-Maktūm (1990–2006) and, since 2006, Sheikh Muhammad ibn Rāshid al-Maktūm.In 2006 the United Arab Emirates held its first elections. A very limited electoral college was permitted to vote for the selection of half of the membership of the advisory Federal National Council, the other half of which would remain designated by appointment.

Foreign relations

The regime of Ruhollah Khomeini (Khomeini, Ruhollah) in Iran and the subsequent Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) created problems for the United Arab Emirates. The resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism posed a double threat to the federation's stability by generating unrest among the Iranian Shīʿites living in the emirates and providing inspiration to the growing numbers of young activist Sunnis, who found the existing political order unsupportive and uncommitted to upholding Islamic values.

Fighting during the Iran-Iraq War broke out within a few miles of the emirates' coast when Iran and Iraq began to attack tankers in the Persian Gulf. The intensity of such threats moved the emirates to join with Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Kuwait to form the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 1981. The council was designed to strengthen the security of its members and to promote economic cooperation. The United Arab Emirates joined Saudi Arabia and the other GCC states in condemning Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990. It provided facilities for Western military forces and contributed troops for the liberation of Kuwait in early 1991. The emirates also became a member of both the United Nations and the Arab League in 1991.

The emirates, backed by fellow GCC members, objected vigorously when in 1992 Iran strengthened its control over the disputed islands of Abū Mūsa and the Tunbs (Ṭunb al-Kubrā and Ṭunb al-Ṣughrā), both seized by Iran in 1971. Iran continued to engage in development activities on the islands throughout the decade, including the establishment of an airport on Abū Mūsa and a power station on Ṭunb al-Kubrā in 1996, further straining relations between the two countries; by 2006 no conclusive resolution to these disputes had been reached. The emirates responded by moving closer to the Western powers while maintaining a confrontational stance toward Iran.

In the late 1990s the federation was one of only three countries—along with Pakistan and Saudi Arabia—to recognize the Taliban regime of Afghanistan. The emirates broke relations with that group in 2001, however, when the Taliban refused to extradite Islamic militant Osama bin Laden (bin Laden, Osama), accused of organizing the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and on the Pentagon outside of Washington, D.C., on September 11.

In early 2006 a fierce debate emerged over the move by state-owned Dubai Ports World (DP World) to take over management of a number of U.S. ports through its acquisition of the British firm that had previously run the ports. Citing security fears, the U.S. Congress threatened to block the deal, which was supported by Pres. George W. Bush. Though political confrontation was averted when DP World committed to divesting of the ports shortly thereafter, the incident provoked strong international debate. In 2007 state-backed Dubai Aerospace Enterprises was also forced to back out of its proposal to purchase a majority stake in the Auckland International Airport in New Zealand; the deal, supported by airport board officials, was faced with overwhelming local council and public opposition.

Additional Reading

Comparative coverage of the states in the Persian Gulf region is provided by Michael Herb, All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies (1999); F. Gregory Gause, III, Oil Monarchies: Domestic and Security Challenges in the Arab Gulf States (1994); John Bulloch, The Persian Gulf Unveiled (also published as The Gulf, 1984); and Alvin J. Cottrell (ed.), The Persian Gulf States: A General Survey (1980). Discussions of early history include Juan R.I. Cole, “Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shiʿism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 19:177–203 (May 1987); Ahmad Mustafa Abu-Hakima, History of Eastern Arabia, 1750–1800: The Rise and Development of Bahrain and Kuwait (1965); and J.B. Kelly, Britain and the Persian Gulf, 1795–1880 (1968). Works on the United Arab Emirates include Frank A. Clements (compiler), United Arab Emirates, rev. ed. (1998); Werner Forman and Michael Asher, Phoenix Rising: The United Arab Emirates, Past, Present & Future (1996); Malcolm C. Peck, The United Arab Emirates: A Venture in Unity (1986); and Ali Mohammed Khalifa, The United Arab Emirates: Unity in Fragmentation (1979). Linda Usra Soffan, The Women of the United Arab Emirates (1980), discusses changes in the status of women. See also Ragaei El Mallakh, The Economic Development of the United Arab Emirates (1981).Historical works include Abdullah Omran Taryam, The Establishment of the United Arab Emirates, 1950–85 (1987); Sulṭān Muḥammad Al-Qāsimī, The Myth of Arab Piracy in the Gulf, 2nd ed. (1988); Frauke Heard-Bey, From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates: A Society in Transition, new ed. (1996); Muhammad Morsy Abdullah, The United Arab Emirates: A Modern History (1978); Rosemarie Said Zahlan, The Origins of the United Arab Emirates (1978); and Clarence C. Mann, Abu Dhabi: Birth of an Oil Shaikhdom, 2nd ed. (1969).

- Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

- Gonzalo Pizarro

- González de Clavijo, Ruy

- González de Mendoza, Pedro, Cardinal

- William B. Allison

- William Barker Cushing

- William Barnes

- William Bateson

- William Baylebridge

- William Baziotes

- William Beaumont

- William Beckford

- William Becknell

- William Beebe

- William Benton

- William Bernard Ullathorne

- William Bernbach

- William Billings

- William Blackwood

- William Blake

- William Bligh

- William Blount

- William Bolcom

- William Booth

- William Bowie