utility and value

economics

Introduction

in economics, the determination of the prices of goods and services.

The modern industrial economy is characterized by a high degree of interdependence of its parts. The supplier of components or raw materials, for example, must deliver the desired quantities of his products at the right moment and in the desired specifications. In economies such as those of western Europe, North America, and Japan, the coordination of these activities is done through the price system. The relative prices of the various inputs (e.g., labour, materials, machinery) tend to determine the proportions in which they will be used. Prices also affect the relative outputs of the various final products, and they determine who will consume them. Value theory, therefore, studies the structure of these decisions, analyzes the influence of prices, and examines the efficiency of the resulting allocation of resources. Value theory is also applied by business firms and government agencies in their decisions that relate to pricing and the allocation of resources.

Theories of value

Cost-of-production analysis

Modern value theory began with Adam Smith (Smith, Adam) (1776), David Ricardo (Ricardo, David) (1817), and a number of other writers, who are generally lumped together as the classical school. These writers sought to explain pricing primarily on the basis of cost of production. That is, if commodity A costs twice as much to produce as commodity B, the price of A will be pushed toward a level twice as high as that of B. If this were not the case—if, for example, A sold for three times the price of B—then the greater profitability of investment in A would cause its production to increase and drive down its price, while the production of B would decline, thus raising its price. Prices would finally be driven to the 2:1 ratio of the costs of production.

The classical economists were well aware of the oversimplification in this explanation, but, as with most theoretical analysis, its strength lay in the amount it was able to explain with a very simple model. (It is highly misleading to interpret the classical analysis literally, as a picture of its authors' views of the complex world of reality.) It was soon recognized, however, that the cost-of-production analysis considered only part of the relevant problem. Since cost depends on the quantity produced (e.g., costs per unit may decline as production of an item increases), the analysis must take into account the demand for the product. The analysis of demand was made possible by the theory of utility, developed by H.H. Gossen in Germany (1854), Karl Menger (Menger, Carl) in Austria (1871), Léon Walras (Walras, Léon) in France (1874–77), and W.S. Jevons (Jevons, William Stanley) in England (1871).

The role of utility analysis in value theory will be discussed later. It need only be added at this point that modern value theory, following the lead of the English economist Alfred Marshall (Marshall, Alfred) (Principles of Economics, 8th ed., 1920), considers prices to be determined simultaneously by cost and demand considerations. The analysis also recognizes the complex interdependencies in the system, with demands and supplies (supply and demand) of various commodities affecting one another.

Resource limitations and allocation

The fact that goods have value can be ascribed ultimately to the limitations in the world's material endowment. Man does not have all the arable land, petroleum, or platinum that he would like; their use must be rationed. That is why goods have prices; if they were available in unlimited supply they would be free. Price usually serves as the rationing (conservation) device whereby their use is kept down to the available supply.

Resources can be said to be scarce in both an absolute and in a relative sense: the surface of the Earth is finite, imposing absolute scarcity; but the scarcity that concerns economists is the relative scarcity of resources (allocation of resources) in different uses. Materials used for one purpose cannot at the same time be used for other purposes; if the quantity of an input is limited, the increased use of it in one manufacturing process must cause it to become scarcer in other uses.

The cost of a product in terms of money may not measure its true cost to society. The true cost of, say, the construction of a supersonic jet is the value of the schools and refrigerators that will never be built as a result. Every act of production uses up some of society's available resources; it means the foregoing of an opportunity to produce something else. In deciding how to use resources most effectively to satisfy the wants of the community, this opportunity cost must ultimately be taken into account.

In a market economy the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied depends on the cost of making it, and that cost, ultimately, is the cost of not making other goods. The market mechanism enforces this relationship. In the first instance, the cost of, say, a pair of shoes is the price of the leather, the labour, the fuel, and other elements used up in producing them. But the price of these inputs, in turn, depends on what they can produce elsewhere—if the handbags that can be produced with the leather are valued very highly by consumers, the price of leather will be bid up correspondingly.

Theories of utility

There are two sides to the analysis of price and value: the supply side and the demand side. If cost can be said to underlie the supply relationship that determines price, the demand side must be taken to reflect consumer tastes and preferences. “Utility” is a concept that has been used to describe these tastes. As already indicated, the cost-of-production analysis of value given above is incomplete, because cost itself depends on the quantity produced. The cost analysis, moreover, applies only to commodities the production of which can be expanded and contracted. The price of a first-folio Shakespeare has no relation to cost of production; it must depend in some sense on its utility to purchasers as it affects their bids.

marginal utility

The classical economists suggested that this leads to a paradox. They argued that utility could not explain the relative price of fine jade and bread, because the latter was for many consumers essential to life, and hence its utility must surely be greater than that of jade. Yet the price of bread is far lower than that of jade. The theory of marginal utility that flowered toward the end of the 19th century supplied the key to the paradox and provided the basis for today's analysis of demand. Marginal utility was defined as the value to the consumer of an additional unit of some commodity. If, for example, the consumer is offered a choice between 22 and 23 slices of bread for his family, marginal utility measures how much more valuable 23 slices are than 22. It is clear that the magnitude of the marginal utility varies with the magnitude of, say, the smaller of the alternatives. That is, for a family of four, the difference between seven and eight slices of bread per day can be substantial, if the family will still be hungry in either case. But the difference in value between 31 and 32 slices may be negligible. If 31 slices offer enough for everyone to fill his stomach, a 32nd slice may be worth very little. Moreover, the difference in value between 122 and 123 slices may be negative—a 123rd slice may just add to the family's disposal problem. These observations lead directly to the plausible notion that marginal utility in some sense diminishes with the base from which one starts the calculation. With only seven or eight slices the marginal utility (incremental value) of an eighth slice is high. With 31 or 32 slices it is lower, and so on. The less scarce a commodity, the lower is its marginal utility, because its possessor in any case will have enough to satisfy his most pressing uses for it, and an increment in his holdings will only permit him to satisfy, in addition, desires of lower priority.

The consumer will be motivated to adjust his purchases so that the price of each and every good will be approximately equal to its marginal utility (that is, to the amount of money he is willing to pay for an additional unit). If the price of an item is P dollars, for example, and the consumer is considering buying, say, 10 units, at which point the marginal utility of the good to him is M (which is greater than P), the consumer will be better off if he purchases 11 rather than 10 units, since the additional unit costs him P dollars. He will keep revising his purchase plans upward until he reaches the point where the marginal utility of the item falls to P dollars. In sum, the consumer's self-interest will lead him (without conscious calculation) to purchase an amount such that the marginal utility is as close as possible to market price. So long as the consumer selects a bundle of purchases that gives him the most benefit (pleasure, utility) for his money, he must end up with quantities such that the marginal utility of each commodity in the bundle is approximately equal to its price.

It now becomes easy to explain the paradox underlying the relationship between the prices of jade and bread. Because a piece of fine jade is scarce, its marginal utility is high, and consumers are willing to pay comparatively high prices for it. The explanation is perfectly consistent with a utility analysis of demand, so long as one relates price to the marginal utility of the item rather than to its total utility. A family's bread may be very valuable to it, but, if it has enough, the marginal utility of the bread will be small, and this will be reflected in its low price.

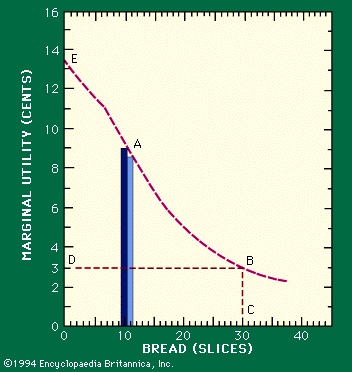

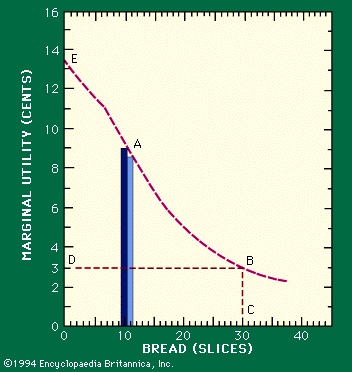

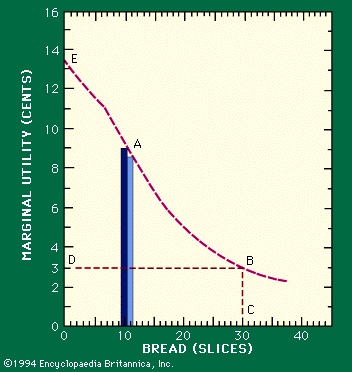

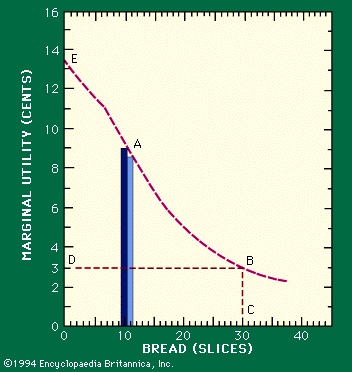

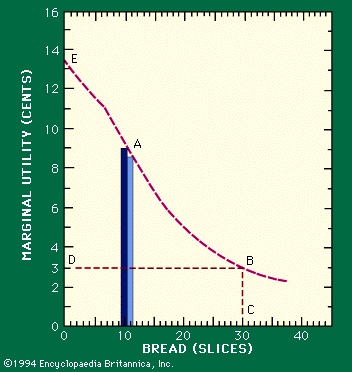

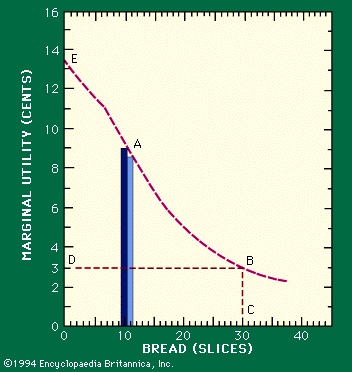

The relationship between price and marginal utility is important not because it explains issues like the jade–bread paradox but because it enables one to analyze the relationship between prices and quantities demanded. It also, as a practical matter, permits one to judge how well any portion of the price mechanism is working as a device to secure the efficient satisfaction of the wants of the public, within the limits set by available resources. The conclusion that at any price the consumer will purchase the quantity at which marginal utility is equal to price makes it possible to draw a demand curve showing—to a reasonable degree of approximation—how the amount demanded will vary with price. A curve based on the previous example of bread consumption is given in Figure 1-->

The relationship between price and marginal utility is important not because it explains issues like the jade–bread paradox but because it enables one to analyze the relationship between prices and quantities demanded. It also, as a practical matter, permits one to judge how well any portion of the price mechanism is working as a device to secure the efficient satisfaction of the wants of the public, within the limits set by available resources. The conclusion that at any price the consumer will purchase the quantity at which marginal utility is equal to price makes it possible to draw a demand curve showing—to a reasonable degree of approximation—how the amount demanded will vary with price. A curve based on the previous example of bread consumption is given in Figure 1--> . This shows that if the family gets 10 slices per day the marginal utility of bread will be nine cents (point A). One may reverse the question and ask how much the family would purchase at any particular price, say three cents. The graph indicates that at this price the quantity would be 30 slices, because only at that quantity is marginal utility equal to the three-cent price (point B). Thus the curve in Figure 1-->

. This shows that if the family gets 10 slices per day the marginal utility of bread will be nine cents (point A). One may reverse the question and ask how much the family would purchase at any particular price, say three cents. The graph indicates that at this price the quantity would be 30 slices, because only at that quantity is marginal utility equal to the three-cent price (point B). Thus the curve in Figure 1--> , to a reasonable degree of approximation, may be able to do double duty: it may serve as a marginal-utility curve relating marginal utility to quantity and, at the same time, as a demand curve relating quantity demanded to price.

, to a reasonable degree of approximation, may be able to do double duty: it may serve as a marginal-utility curve relating marginal utility to quantity and, at the same time, as a demand curve relating quantity demanded to price.Consumers' surplus

Figure 1-->

Figure 1--> leads to an important conclusion about the consumer's gains from his purchases. The diagram shows that the difference between 10 and 11 slices of bread is worth nine cents to the consumer (marginal utility = nine cents). Similarly, a 12th slice of bread is worth eight cents (see the shaded bars). Thus, the two slices of bread together are worth 17 cents, the area of the two rectangles together. Suppose the price of bread is actually three cents, and the consumer, therefore, purchases 30 slices per day. The total value of his purchases to him is the sum of the areas of all such rectangles for each of the 30 slices; i.e., it is (approximately) equal to all of the area under the demand curve; that is, the area defined by the points 0CBE. The amount the consumer pays, however, is less than this area. His total expenditure is given by the area of rectangle 0CBD—90 cents. The difference between these two areas, the quasi-triangular area DBE, represents how much more the consumer would be willing to spend on the bread over and above the 90 cents he actually pays for it, if he were forced to do so. It represents the absolute maximum that could be extracted from the consumer for the bread by an unscrupulous merchant who had cornered the market. Since, normally, the consumer only pays quantity 0CBD, the area DBE is a net gain derived by the consumer from the transaction. It is called consumers' surplus (consumer surplus). Virtually every purchase yields such a surplus to the buyer.

leads to an important conclusion about the consumer's gains from his purchases. The diagram shows that the difference between 10 and 11 slices of bread is worth nine cents to the consumer (marginal utility = nine cents). Similarly, a 12th slice of bread is worth eight cents (see the shaded bars). Thus, the two slices of bread together are worth 17 cents, the area of the two rectangles together. Suppose the price of bread is actually three cents, and the consumer, therefore, purchases 30 slices per day. The total value of his purchases to him is the sum of the areas of all such rectangles for each of the 30 slices; i.e., it is (approximately) equal to all of the area under the demand curve; that is, the area defined by the points 0CBE. The amount the consumer pays, however, is less than this area. His total expenditure is given by the area of rectangle 0CBD—90 cents. The difference between these two areas, the quasi-triangular area DBE, represents how much more the consumer would be willing to spend on the bread over and above the 90 cents he actually pays for it, if he were forced to do so. It represents the absolute maximum that could be extracted from the consumer for the bread by an unscrupulous merchant who had cornered the market. Since, normally, the consumer only pays quantity 0CBD, the area DBE is a net gain derived by the consumer from the transaction. It is called consumers' surplus (consumer surplus). Virtually every purchase yields such a surplus to the buyer.The concept of consumers' surplus is important for public (public administration) policy, because it offers at least a crude measure of the public benefits of various types of economic activity. In deciding whether a government agency should build a dam, for example, one may estimate the consumers' surplus from the electricity the dam would generate and seek to compare it with the surplus that could be yielded by alternative uses of the resources needed to construct and operate the dam.

Utility measurement and ordinal utility

As originally conceived, utility was taken to be a subjective measure of strength of feeling. An item that might be described as worth “40 utils” was to be interpreted to yield “twice as much pleasure” as one valued at 20 utils. It was not long before the usefulness of this concept was questioned. It was criticized for its subjectivity and the difficulty (if not impossibility) of quantifying it. An alternative line of analysis developed that was able to accomplish most of the same purposes but without as many assumptions. First introduced by the economists F.Y. Edgeworth in England (1881) and Vilfredo Pareto in Italy (1896–97), it was brought to fruition by Eugen Slutsky in Russia (1915) and J.R. Hicks and R.D.G. Allen in Great Britain (1934). The idea was that to analyze consumer choice between, say, two bundles of commodities, A and B, given their costs, one need know only that one is preferred to another. This may at first seem a trivial observation, but it is not as simple as it sounds.

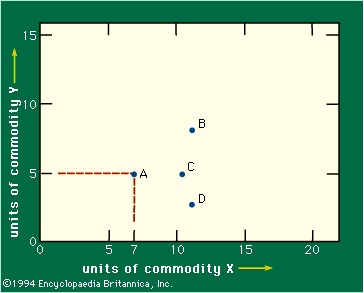

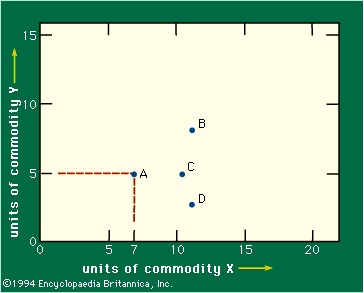

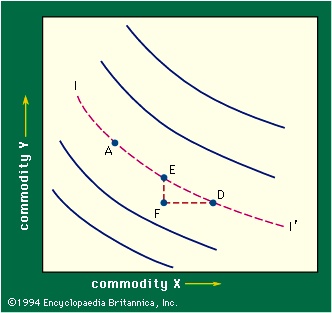

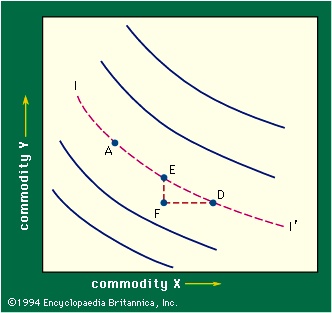

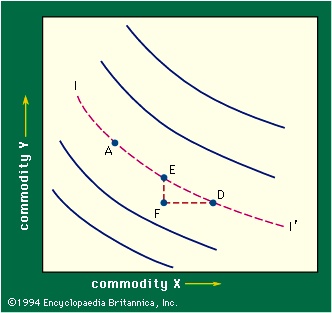

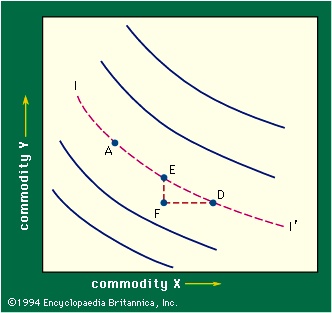

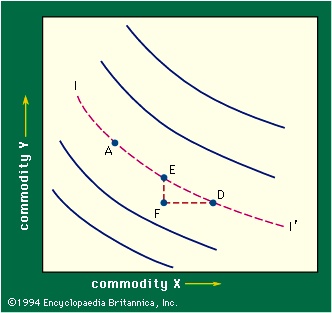

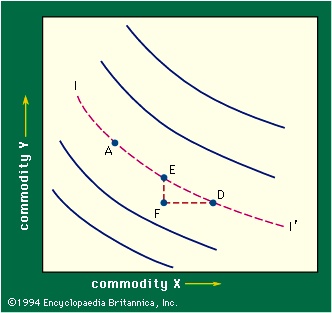

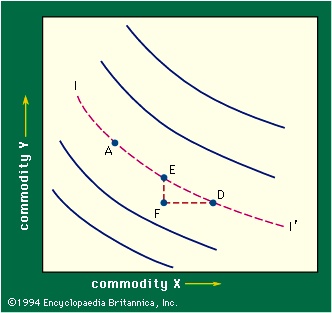

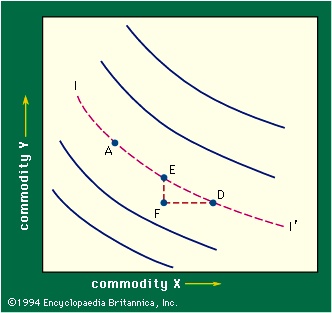

In the following discussion, it is assumed for simplicity that there are only two commodities in the world. Figure 2-->

In the following discussion, it is assumed for simplicity that there are only two commodities in the world. Figure 2--> is a graph in which the axes measure the quantities of two commodities, X and Y. Thus, point A represents a bundle composed of seven units of commodity X and five units of commodity Y. The assumption is made that the consumer prefers to own more of either or both commodities. That means he must prefer bundle C to bundle A, because C lies directly to the right of A and hence contains more of X and no less of Y. Similarly, B must be preferred to A. But one cannot say, in general, whether A is preferred to D or vice versa, since one offers more of X and the other more of Y.

is a graph in which the axes measure the quantities of two commodities, X and Y. Thus, point A represents a bundle composed of seven units of commodity X and five units of commodity Y. The assumption is made that the consumer prefers to own more of either or both commodities. That means he must prefer bundle C to bundle A, because C lies directly to the right of A and hence contains more of X and no less of Y. Similarly, B must be preferred to A. But one cannot say, in general, whether A is preferred to D or vice versa, since one offers more of X and the other more of Y.

The consumer may in fact not care whether he receives A or D—that is, he may be indifferent (indifference) (see Figure 3-->

The consumer may in fact not care whether he receives A or D—that is, he may be indifferent (indifference) (see Figure 3--> ). Assuming that there is some continuity in his preferences, there will be a locus connecting A and D, any point on which (E or A or D) represents bundles of commodities of equal interest to this consumer. This locus (I–I′ in Figure 3-->

). Assuming that there is some continuity in his preferences, there will be a locus connecting A and D, any point on which (E or A or D) represents bundles of commodities of equal interest to this consumer. This locus (I–I′ in Figure 3--> ) is called an indifference curve. It represents the consumer's subjective trade off between the two commodities—how much more of one he will have to get to make up for the loss of a given amount of another. That is, one may treat the choice between bundle D and bundle E as involving the comparison of the gain of quantity FD of X with the loss of FE of Y. If the consumer is indifferent between D and E, the gain and loss just offset one another; hence, they indicate the proportion in which he is willing to exchange the two commodities. In mathematical terms, FE divided by FD represents the average slope of the indifference curve over arc ED; it is called the marginal rate of substitution between X and Y.

) is called an indifference curve. It represents the consumer's subjective trade off between the two commodities—how much more of one he will have to get to make up for the loss of a given amount of another. That is, one may treat the choice between bundle D and bundle E as involving the comparison of the gain of quantity FD of X with the loss of FE of Y. If the consumer is indifferent between D and E, the gain and loss just offset one another; hence, they indicate the proportion in which he is willing to exchange the two commodities. In mathematical terms, FE divided by FD represents the average slope of the indifference curve over arc ED; it is called the marginal rate of substitution between X and Y.

Figure 3-->

Figure 3--> also contains other indifference curves, some representing combinations preferred to A (curves lying above and to the right of A) and some representing combinations to which A is preferred. These are like contour lines on a map, each such line being a locus of combinations that the consumer considers equally desirable. Conceptually, through every point in the diagram there is an indifference curve. Figure 3-->

also contains other indifference curves, some representing combinations preferred to A (curves lying above and to the right of A) and some representing combinations to which A is preferred. These are like contour lines on a map, each such line being a locus of combinations that the consumer considers equally desirable. Conceptually, through every point in the diagram there is an indifference curve. Figure 3--> , with its family of indifference curves, is called an indifference map. This map obviously does no more than rank the available possibilities; it indicates whether one point is preferred to another but not by how much it is preferred.

, with its family of indifference curves, is called an indifference map. This map obviously does no more than rank the available possibilities; it indicates whether one point is preferred to another but not by how much it is preferred.It is easy to show that at any point such as E the slope of the indifference curve, roughly FE divided by ED, equals the ratio of the marginal utility of X to the marginal utility of Y for the corresponding quantities. For in moving from E to D the consumer gives up FE of Y, a loss valued, by definition, at approximately FE multiplied by the marginal utility of Y, and he gains FD of X, a gain worth FD multiplied by the marginal utility of X. Relative marginal utilities can be measured in this way because their ratio does not measure subjective quantities—rather, it represents a rate of exchange of two commodities. The marginal utility of X measured in money terms tells one how much of the commodity used as money the consumer is willing to give for more of the commodity X but not what psychic pleasure the consumer gains.

Prices and incomes

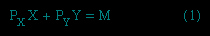

One other type of information is needed to complete the analysis of consumer choice: the prices of X and Y and the amount the consumer has available to spend. In what follows, it will be assumed that the consumer spends all his money on the available commodities (savings bonds being among the commodities). If PX and PY are the prices of commodities X and Y, respectively, and M represents the amount of money available for spending, the condition that all of the money is spent yields the equation

or, solving for Y in terms of X,

(2)This is obviously the equation of a straight line with slope

and with y-intercept

.

The line, called the budget line, or price line, represents all the combinations of X and Y that the consumer can afford to buy with income M at the given prices.

Equilibrium of the consumer

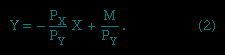

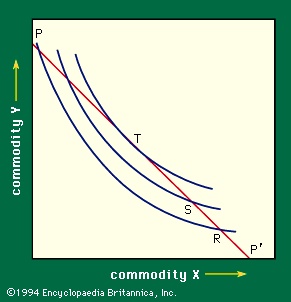

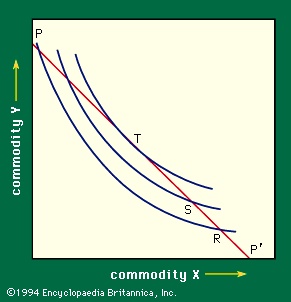

Figure 4-->

Figure 4--> combines this price line and the indifference curves, permitting direct analysis of the consumer purchase decision. Line PP′ is the price line corresponding to equation (2) above. Any point R on that line represents a combination of X and Y that a given consumer can afford to purchase; however, R is not an optimal choice. This can be seen by comparing R with S on the same price line. Since S lies on a higher indifference curve than R, the former is the preferred position, and, since S costs no more than R (they are on the same price line, so each costs M dollars), S gives the consumer more for his money. It is at T, however, the point of tangency between the price line and an indifference curve, that the consumer reaches his highest indifference curve; this is, therefore, the optimal point for him, given his pattern of tastes as shown by the shapes of his indifference curves. This is the solution of the choice problem—it explains, in principle, the consumer's purchase decision on the basis of his given preferences, with no assumptions as to degrees of measurable utility.

combines this price line and the indifference curves, permitting direct analysis of the consumer purchase decision. Line PP′ is the price line corresponding to equation (2) above. Any point R on that line represents a combination of X and Y that a given consumer can afford to purchase; however, R is not an optimal choice. This can be seen by comparing R with S on the same price line. Since S lies on a higher indifference curve than R, the former is the preferred position, and, since S costs no more than R (they are on the same price line, so each costs M dollars), S gives the consumer more for his money. It is at T, however, the point of tangency between the price line and an indifference curve, that the consumer reaches his highest indifference curve; this is, therefore, the optimal point for him, given his pattern of tastes as shown by the shapes of his indifference curves. This is the solution of the choice problem—it explains, in principle, the consumer's purchase decision on the basis of his given preferences, with no assumptions as to degrees of measurable utility. The tangency at the solution point has a significant interpretation. It was noted above that the slope of the indifference curve is the ratio of the marginal utilities of the two commodities. It follows that, at the optimal point T, a dollar of expenditure must offer the same utility whether spent on X or on Y. If this is not so—as at point R in Figure 4-->

The tangency at the solution point has a significant interpretation. It was noted above that the slope of the indifference curve is the ratio of the marginal utilities of the two commodities. It follows that, at the optimal point T, a dollar of expenditure must offer the same utility whether spent on X or on Y. If this is not so—as at point R in Figure 4--> , where the consumer gets more for his money by spending a dollar on Y rather than on X—it will pay him to reallocate his expenditures between the two commodities accordingly, moving toward S from R.

, where the consumer gets more for his money by spending a dollar on Y rather than on X—it will pay him to reallocate his expenditures between the two commodities accordingly, moving toward S from R.Changes in prices and incomes

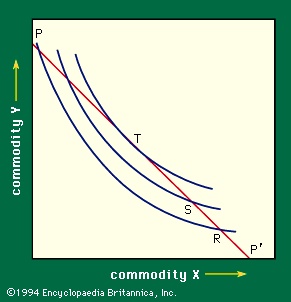

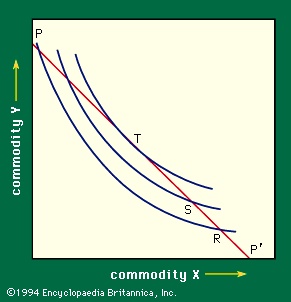

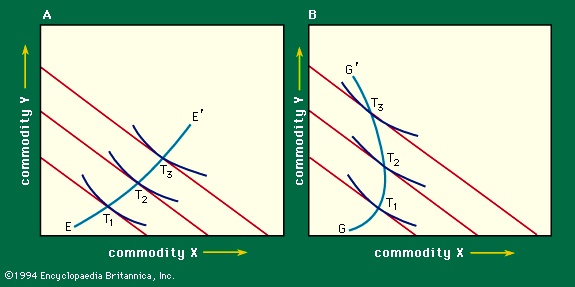

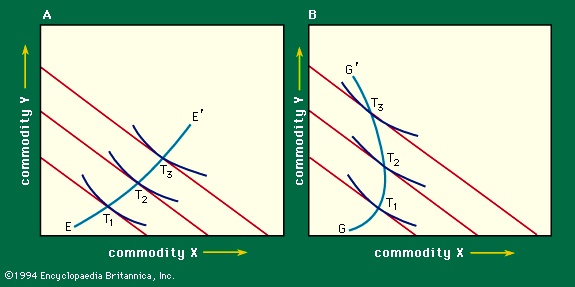

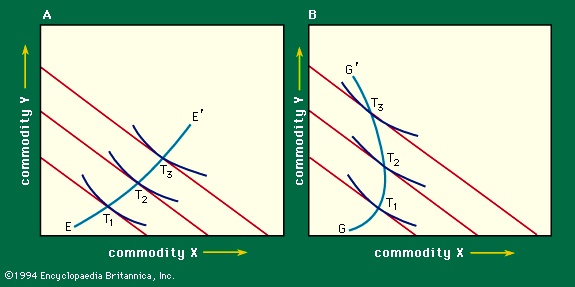

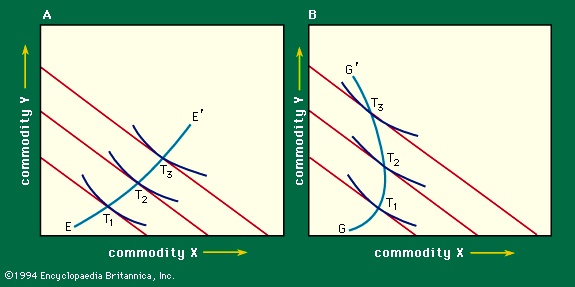

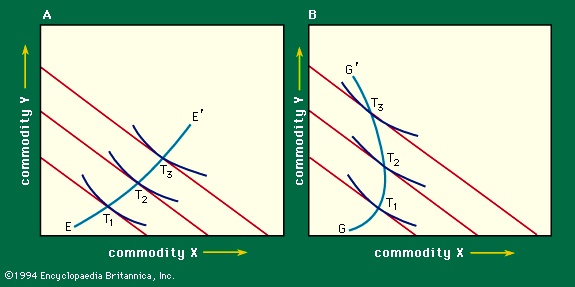

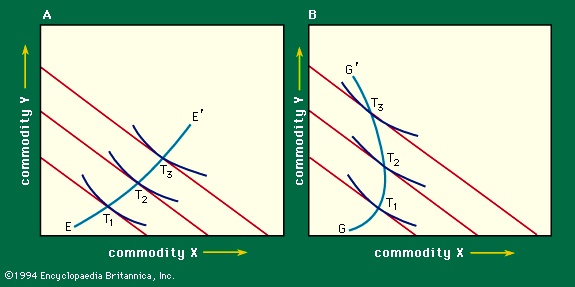

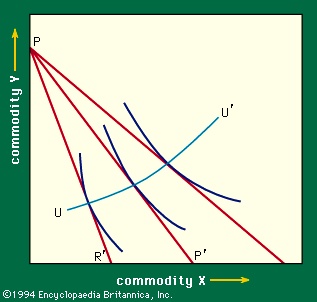

The diagram becomes more illuminating when one investigates how the consumer's decision is affected by a change in his income or in the price of a commodity. Equation (2) indicates that a change in income, M, does not affect the slope of the price line, only its intercept. Thus, as the person's income increases, the price line undergoes a sequence of parallel shifts (Figure 5-->

The diagram becomes more illuminating when one investigates how the consumer's decision is affected by a change in his income or in the price of a commodity. Equation (2) indicates that a change in income, M, does not affect the slope of the price line, only its intercept. Thus, as the person's income increases, the price line undergoes a sequence of parallel shifts (Figure 5--> ). For each such line there will be a point of tangency, T, with an indifference curve, showing the consumer's optimal bundle of purchases with the corresponding income. The locus of these points (T1, T2, T3 . . .) may be called the income–consumption curve; it shows how the consumer's purchases vary with his income. Normally the curve will have a positive slope, as EE′ does in Figure 5A-->

). For each such line there will be a point of tangency, T, with an indifference curve, showing the consumer's optimal bundle of purchases with the corresponding income. The locus of these points (T1, T2, T3 . . .) may be called the income–consumption curve; it shows how the consumer's purchases vary with his income. Normally the curve will have a positive slope, as EE′ does in Figure 5A--> , meaning that as a person grows wealthier he will buy more of each commodity. But the slope can be negative for some stretches (GG′ in Figure 5B-->

, meaning that as a person grows wealthier he will buy more of each commodity. But the slope can be negative for some stretches (GG′ in Figure 5B--> ). In that case, X is said to be an inferior good of which the consumer buys less as his income rises.

). In that case, X is said to be an inferior good of which the consumer buys less as his income rises. The diagram can also be used to show what happens as the price of X varies. From equation (2) it can be seen that the Y-intercept is not affected by an increase in the price of X but that the slope of the price line grows. Thus, as PX rises, the price line shifts from PP′ to PR′ in Figure 6-->

The diagram can also be used to show what happens as the price of X varies. From equation (2) it can be seen that the Y-intercept is not affected by an increase in the price of X but that the slope of the price line grows. Thus, as PX rises, the price line shifts from PP′ to PR′ in Figure 6--> . This means that, as PX rises, M dollars will buy as much of good Y as before (the position of point P at which all M dollars are spent on commodity Y does not change), but that M dollars will now buy less of good X, so that the position of point P′ must move toward the left. Once again, by following the points of tangency between indifference curves and the price lines for various values of PX, one contains a locus UU′, τηε price–consumption curve, showing how the consumer's purchases vary with PX.

. This means that, as PX rises, M dollars will buy as much of good Y as before (the position of point P at which all M dollars are spent on commodity Y does not change), but that M dollars will now buy less of good X, so that the position of point P′ must move toward the left. Once again, by following the points of tangency between indifference curves and the price lines for various values of PX, one contains a locus UU′, τηε price–consumption curve, showing how the consumer's purchases vary with PX.Income and substitution effects

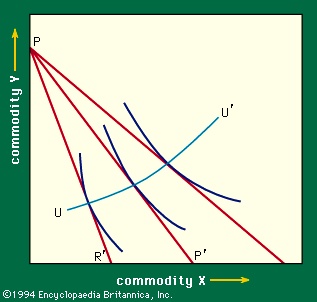

It is useful to divide the effects of the price change conceptually into two parts. An increase in the price of X obviously affects the relative cost of X and Y. But it also decreases the consumer's overall purchasing power. The effect on purchases of this reduction of purchasing power is called the income effect of the price change. Its effect via the relative price change is called the substitution effect. The division can be carried out graphically as follows: let the price of X increase so that the price line in Figure 7-->

It is useful to divide the effects of the price change conceptually into two parts. An increase in the price of X obviously affects the relative cost of X and Y. But it also decreases the consumer's overall purchasing power. The effect on purchases of this reduction of purchasing power is called the income effect of the price change. Its effect via the relative price change is called the substitution effect. The division can be carried out graphically as follows: let the price of X increase so that the price line in Figure 7--> moves from PP′ to PR′, and assume an imaginary intermediate price line, LL′, with the slope of PR′ but tangent to the indifference curve that was attained with the old price line PP′. The imaginary price line has the following properties: (1) it involves the same real income as PP′ (tangency points T and S are the same indifference curve), and (2) it involves the same relative prices as the new price line since their slopes are the same. The rise in price has, in the figure, caused the demand for X to fall from C to A (the quantities of X corresponding to tangency points T and U). It has been possible to divide the total effect, CA, into two parts, the income effect, BA, and the substitution effect, CB. This breakdown is important, because a number of interesting and important theorems can be proved about the substitution effect. Two of these theorems will illustrate the point.

moves from PP′ to PR′, and assume an imaginary intermediate price line, LL′, with the slope of PR′ but tangent to the indifference curve that was attained with the old price line PP′. The imaginary price line has the following properties: (1) it involves the same real income as PP′ (tangency points T and S are the same indifference curve), and (2) it involves the same relative prices as the new price line since their slopes are the same. The rise in price has, in the figure, caused the demand for X to fall from C to A (the quantities of X corresponding to tangency points T and U). It has been possible to divide the total effect, CA, into two parts, the income effect, BA, and the substitution effect, CB. This breakdown is important, because a number of interesting and important theorems can be proved about the substitution effect. Two of these theorems will illustrate the point.Under the normal assumptions of demand theory it can be proved that a rise in the price of X must, via the substitution effect, work to reduce the demand for X; the second theorem states the surprising result that, considering only substitution effects, a dollar rise in the price of X must change the demand for Y by precisely the same amount as a dollar rise in the price of Y changes the demand for X. Similar relationships have been shown to hold when there are more than two commodities involved.

Additional Reading

Two good introductory discussions of the nature of value theory and its application to the economy as a whole are Robert Dorfman, The Price System (1964), and Prices and Markets, 3rd ed. (1978). The classic work on the history of economic theory, particularly of value theory, is Joseph Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, ed. by Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter (1954, reissued 1986). An excellent brief discussion can be found in George J. Stigler, Essays in the History of Economics (1965, reprinted 1987), especially essays 5, 6, and 12. Three rather advanced works on modern value theory are J.R. Hicks, Value and Capital, 2nd ed. (1950, reissued 1974); Paul A. Samuelson, Foundations of Economic Analysis, enlarged ed. (1983); and J. Hüsler and R.-D. Reiss (eds.), Extreme Value Theory (1989), containing conference proceedings. Marc R. Tool, Essays in Social Value Theory: A Neo-Institutionalist Contribution (1986), provides very insightful views.Seminal works in the history of value theory include David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817, reissued 1981); F.Y. Edgeworth, Mathematical Psychics (1881, reprinted 1967); Vilfredo Pareto, Cours d'économie politique, 2 vol. (1896–97); J.R. Hicks and R.D.G. Allen, “A Reconsideration of the Theory of Value,” Economica, New Series, 2 parts, 1:52–76,196–219 (1934); R.G.D. Allen, “Professor Slutsky's Theory of Consumers' Choice,” The Review of Economic Studies, 3:120–129 (1936); Carl Menger, Principles of Economics (1950, reissued 1981; originally published in German, 1871); Léon Walras, Elements of Pure Economics; or, The Theory of Social Wealth (1954, reprinted 1984; originally published in French, 1874); W. Stanley Jevons, The Theory of Political Economy, 5th ed. (1957); Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics, 9th ed., 2 vol. (1961), also discussing price; John Weeks, Capital and Exploitation (1981), a study of Marx's labour theory of value; Hermann Heinrich Gossen, The Laws of Human Relations and the Rules of Human Action Derived Therefrom (1983; originally published in German, 1854); and K.K. Valtukh, Marx's Theory of Commodity and Surplus-Value: Formalised Exposition, trans. from Russian (1987). Two good discussions of the more recently popular theories of utility are David M. Kreps, Notes on the Theory of Choice (1988); and Bill Gerrard (ed.), The Economics of Rationality (1993).Among the best modern textbooks in microeconomics are David D. Friedman, Price Theory, 2nd ed. (1990), an introductory text which includes nonconventional applications of price theory; David M. Kreps, A Course in Microeconomic Theory (1990), for intermediate and advanced readership; and Hal R. Varian, Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd ed. (1992), and Intermediate Microeconomics, 3rd ed. (1993), both at an advanced level. Ed.