football, gridiron

sport

Introduction

version of the sport of football so named for the vertical yard lines marking the rectangular field. Gridiron football evolved from English rugby and soccer (association football); it differs from soccer (football (soccer)) chiefly in allowing players to touch, throw, and carry the ball with their hands, and it differs from rugby in allowing each side to control the ball in alternating possessions. The sport, played with 11 on each side, originated in the United States, where it was largely developed and eventually became the country's leading spectator sport. It quickly spread to Canada (where it evolved into a 12-man game), though it never achieved the great popularity and status of ice hockey there. Gridiron football has not been taken up in the rest of the world to the same degree as other American sports such as basketball and baseball. Since the 1980s, however, primarily through the marketing efforts of the National Football League, teams and leagues have been established in Europe, and the game has achieved a degree of international popularity through television.

version of the sport of football so named for the vertical yard lines marking the rectangular field. Gridiron football evolved from English rugby and soccer (association football); it differs from soccer (football (soccer)) chiefly in allowing players to touch, throw, and carry the ball with their hands, and it differs from rugby in allowing each side to control the ball in alternating possessions. The sport, played with 11 on each side, originated in the United States, where it was largely developed and eventually became the country's leading spectator sport. It quickly spread to Canada (where it evolved into a 12-man game), though it never achieved the great popularity and status of ice hockey there. Gridiron football has not been taken up in the rest of the world to the same degree as other American sports such as basketball and baseball. Since the 1980s, however, primarily through the marketing efforts of the National Football League, teams and leagues have been established in Europe, and the game has achieved a degree of international popularity through television.Football in the United States

The game emerges

Roots in soccer (football (soccer)) and rugby

Gridiron football was the creation of elite American universities (university), a fact that has shaped its distinctive role in American culture and life. After several decades of informal, student-organized games that were tolerated by faculty as an alternative to more destructive rowdiness, the first intercollegiate football game was played on November 6, 1869, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, between in-state rivals Princeton (Princeton University) and Rutgers (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey) according to rules adapted from those of the London Football Association. This soccer-style game became the dominant form as Columbia, Cornell, Yale (Yale University), and a few other colleges in the Northeast took up the sport in the early 1870s, and in 1873 representatives from Princeton, Yale, and Rutgers met in New York City to found the Intercollegiate Football Association and to adopt a common code. Conspicuously missing was Harvard (Harvard University), the country's premier university, whose team insisted on playing the so-called “Boston Game,” a cross between soccer and rugby. In May 1874, in the second of two matches with McGill University of Montreal (the first was played by the rules of the Boston Game), Harvard's players were introduced to the rugby game and immediately preferred it to their own. The following year, for Harvard's first football contest with Yale, representatives of the two schools agreed on “concessionary rules” that were chiefly Harvard's. When spectators (including Princeton students) as well as Yale players saw the advantages of the rugby style, the stage was set for a meeting in 1876 of representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia to form a new Intercollegiate Football Association based on rugby rules.

Walter Camp (Camp, Walter) and the creation of American football

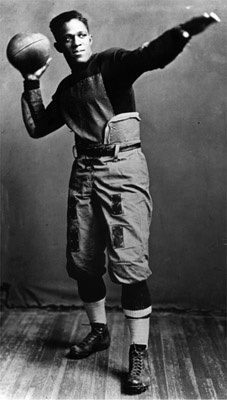

Harvard made the first breach in rugby rules. Rejecting the traditional manner of putting the ball in play—players from both teams massed about the ball in a “scrummage,” or “scrum,” trying to kick it forward through the mass of players—Harvard opted for “heeling it out,” or kicking the ball backward to a teammate. The further transformation of English rugby into American football came chiefly through the efforts of Walter Camp (Camp, Walter), who even during his lifetime was known as the “Father of American Football.” As an undergraduate and then a medical student at Yale, Camp played football from 1876 through 1881, but—more important—beginning in 1878, he dominated the rules committee for nearly three crucial decades. Two of Camp's revisions in particular effectively created the gridiron game. The first, in 1880, further refined Harvard's initial innovation, abolishing the scrummage altogether in favour of a scrimmage, which awarded possession of the ball to one of the two teams. It was then put in play by heeling it out. (Snapping the ball with the hand became legal in 1890, though snapping with the foot continued as an option until 1913.) The second crucial rule change was necessitated by the first. Camp's more orderly manner of initiating play did not require the team in possession of the ball to give it up. After Princeton simply held the ball for an entire half in its 1880 and 1881 contests with Yale, both games ending in scoreless ties that bored spectators as much as they frustrated Yale's players, Camp proposed a rule that a team must advance the ball 5 yards or lose 10 in three downs (plays), or it would be obliged to surrender the ball to the other side. Camp was also responsible for having 11 players on a side, for devising a new scoring system in 1883 with two points for a touchdown, four points for the goal after a touchdown, and five points for a field goal (a field goal became worth three points in 1909, a touchdown six points in 1912), for naming the positions (centre, guard, tackle, end, quarterback, halfback, fullback), for marking the field with stripes, and for proposing several other innovations; but it was those two simple rules adopted in 1880 and 1882 that most fundamentally created American football.

Harvard made the first breach in rugby rules. Rejecting the traditional manner of putting the ball in play—players from both teams massed about the ball in a “scrummage,” or “scrum,” trying to kick it forward through the mass of players—Harvard opted for “heeling it out,” or kicking the ball backward to a teammate. The further transformation of English rugby into American football came chiefly through the efforts of Walter Camp (Camp, Walter), who even during his lifetime was known as the “Father of American Football.” As an undergraduate and then a medical student at Yale, Camp played football from 1876 through 1881, but—more important—beginning in 1878, he dominated the rules committee for nearly three crucial decades. Two of Camp's revisions in particular effectively created the gridiron game. The first, in 1880, further refined Harvard's initial innovation, abolishing the scrummage altogether in favour of a scrimmage, which awarded possession of the ball to one of the two teams. It was then put in play by heeling it out. (Snapping the ball with the hand became legal in 1890, though snapping with the foot continued as an option until 1913.) The second crucial rule change was necessitated by the first. Camp's more orderly manner of initiating play did not require the team in possession of the ball to give it up. After Princeton simply held the ball for an entire half in its 1880 and 1881 contests with Yale, both games ending in scoreless ties that bored spectators as much as they frustrated Yale's players, Camp proposed a rule that a team must advance the ball 5 yards or lose 10 in three downs (plays), or it would be obliged to surrender the ball to the other side. Camp was also responsible for having 11 players on a side, for devising a new scoring system in 1883 with two points for a touchdown, four points for the goal after a touchdown, and five points for a field goal (a field goal became worth three points in 1909, a touchdown six points in 1912), for naming the positions (centre, guard, tackle, end, quarterback, halfback, fullback), for marking the field with stripes, and for proposing several other innovations; but it was those two simple rules adopted in 1880 and 1882 that most fundamentally created American football.After the crucial rule changes, the play of the game was relatively open, featuring long runs and numerous lateral passes, as in rugby. In 1888 Camp proposed that tackling below the waist be legalized, in order to offset the advantage of speedy backs streaking around the ends. The new rule resulted in the rise of mass plays, an offensive strategy that massed players on a single point of the defense, most famously in Harvard's “flying wedge” in 1892. This style of play proved so brutal that the game was nearly abolished in the 1890s and early 1900s.

Managing the violence of the game

The spirit of early football can be glimpsed in the introduction of a rule in 1894 that banned projecting nails or iron plates in shoes and any metal substance on the player's person. Rules establishing boundaries between permissible and impermissible violence have been continually revised over the years, sometimes in response to periods of heightened concern over deaths and injuries (in the early 1930s as well as the 1890s, for example). To ensure greater safety, the number of officials grew from two in 1873 to seven by 1983. Over time, improvements in equipment also provided more safeguards against serious injuries. In the 1890s players' only protection against blows to the head came from their own long hair and leather nose guards. The first headgear, in 1896, consisted simply of three leather straps. It evolved into close-fitting leather caps with ear flaps. The suspension helmet, which used straps to create space between the helmet shell and the head of the wearer, was introduced in 1917. However, helmets were not required in college football until 1939 (1943 for the National Football League). Improved equipment sometimes increased rather than curtailed the game's dangers. The plastic helmet, introduced in 1939, became a potentially lethal weapon, eventually requiring rules against “spearing”—using the head to initiate contact.

Expansion and reform

In 1879 the University of Michigan (Michigan, University of) and Racine College of Wisconsin inaugurated football in the Midwest. Michigan under Fielding Yost (Yost, Fielding) in 1901–05 and the University of Chicago (Chicago, University of) under Amos Alonzo Stagg (Stagg, Amos Alonzo) in 1905–09 emerged as major powers. The game also spread throughout the rest of the country by the 1890s, though the Big Three—Harvard, Yale, and Princeton—continued to dominate the collegiate football world into the 1920s. Ever mindful of their superiority to the latecomers, the three (joined by the University of Pennsylvania to create briefly a Big Four) formed the Intercollegiate Rules Committee in 1894, separate from the Intercollegiate Football Association. In 1895 in the Midwest, colleges dissatisfied with this divided leadership asserted their independence by forming what became the Western (now the Big Ten (Big Ten Conference)) Conference. The game also spread to the South and West, though conferences were not formed until later in those regions.

In 1879 the University of Michigan (Michigan, University of) and Racine College of Wisconsin inaugurated football in the Midwest. Michigan under Fielding Yost (Yost, Fielding) in 1901–05 and the University of Chicago (Chicago, University of) under Amos Alonzo Stagg (Stagg, Amos Alonzo) in 1905–09 emerged as major powers. The game also spread throughout the rest of the country by the 1890s, though the Big Three—Harvard, Yale, and Princeton—continued to dominate the collegiate football world into the 1920s. Ever mindful of their superiority to the latecomers, the three (joined by the University of Pennsylvania to create briefly a Big Four) formed the Intercollegiate Rules Committee in 1894, separate from the Intercollegiate Football Association. In 1895 in the Midwest, colleges dissatisfied with this divided leadership asserted their independence by forming what became the Western (now the Big Ten (Big Ten Conference)) Conference. The game also spread to the South and West, though conferences were not formed until later in those regions.The brutality of mass play also spread through the nation; over the course of the 1905 season, 18 young men died from football injuries. Concerned that football might be abolished altogether, President Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Theodore) in October 1905 summoned representatives (including Camp) from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to the White House, where he urged them to reform the game. On December 28 of that year representatives from 62 colleges and universities (not including the Big Three, who would continue for decades to balk at submitting to the will of “inferior” institutions) met in New York to form the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, which became the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1910. To reduce mass play, the group at its initial meeting increased the yardage required for a first down from 5 yards to 10 and legalized the forward pass, the final element in the creation of the game of American football. The founding of the NCAA effectively ended the period when the Big Three (and Walter Camp personally) dictated rules of play to the rest of the football world. It also ended student involvement in controlling the game, though the question of who should rule college football—coaches, alumni and boosters, or college administrators—would continue to bedevil the NCAA throughout its history.

Brutality did not end with the revised rules of 1906. New crises prompted additional rule changes in 1910 (requiring seven men on the line of scrimmage) and 1912 (increasing the number of downs to gain 10 yards from three to four) to eliminate mass play. Nor did the forward pass immediately transform the game. The restrictive 1906 rules made passes riskier than fumbles, and it was only after several years of cautious experimentation that Notre Dame's upset of Army in 1913 highlighted the remarkable possibilities in the passing game. It would be another three decades, however—during which restrictive rules were gradually dropped and the circumference of the ball reduced to facilitate passing—before those possibilities could be fully realized.

Sport and spectacle

This early period in American football was formative in another way as well. Beginning in 1876, the original Intercollegiate Football Association staged a championship game at the end of each season, on Thanksgiving Day, matching the two best teams from the previous year. Initially the game was played in Hoboken, New Jersey, but in 1880 it was shifted to New York City to make it easier for students from all the universities in the association to attend the game. The attendance for that first contest in New York was 5,000. By 1884 it had climbed to 15,000; it rose to 25,000 by 1890 and 40,000 by 1893, the last Thanksgiving Day game to be played in the city. By this time, accounts of the game in New York's major newspapers were taking up as much as three pages in an eight-page paper, and wire services carried reports to every corner of the country. By the 1890s an extracurricular activity at a handful of elite northeastern universities was becoming a spectator sport with a nationwide audience. College football became known for its bands and cheerleaders, pep rallies and bonfires, and homecoming dances and alumni reunions as much as for its athletic thrills. Pursuing the institution's educational mission while serving the public's desire for entertainment posed a dilemma with which college administrators struggled for more than a century. For some of the public, college football's association with institutions of higher education and immersion in college spirit imbued the game with a kind of amateur purity. For others, the colleges' profession of commitment to academic goals while commercializing their sports teams only smacked of hypocrisy.

College football's golden age

After World War I had put the game temporarily on hold, college football fully came of age in the 1920s, when it became widely recognized as America's greatest sporting spectacle (as opposed to baseball, which was the national pastime). The first football stadiums (stadium) at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton were modeled on the ancient Greek stadium and the Roman Colosseum, their architecture revealing much about football's cultural status. With a stadium-building boom in the 1920s, attendance more than doubled, exceeding 10 million by the end of the decade, and newspaper coverage of the sport expanded at a similar rate. The daily newspaper had played a crucial role in the 1880s and '90s, introducing football to a popular audience with no connection to universities and their teams. Commercial radio appeared in 1920 and began regularly broadcasting football games a year later. By the end of the decade three networks were broadcasting a slate of games each Saturday, and local stations were covering all the home teams' games. By 1929 five newsreel companies were devoting roughly one-fifth to one-fourth of their footage to football in the fall. General-interest magazines such as Collier's and the Saturday Evening Post regularly published articles by or about famous coaches or players, along with short stories about the star who wins both the girl and the big game. Movie theaters each fall screened a handful of college football musicals and melodramas with kidnapped heroes who escaped just in the nick of time to score the winning touchdown.

Red Grange (Grange, Red) and professionalism

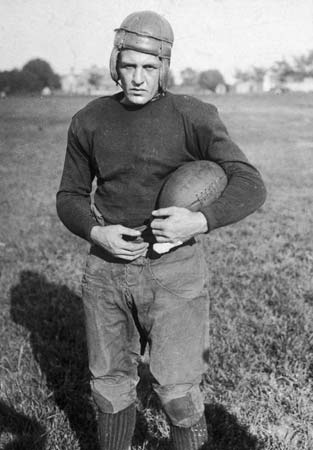

The 1920s saw the emergence of Red Grange (Grange, Red) as football's first true celebrity. Grange received national acclaim for his brilliant performances in games against Michigan and Pennsylvania, but he also created the sport's greatest controversy since the 1906 rule changes when he left the University of Illinois (without graduating) to join the Chicago Bears of the professional National Football League. “Professionalism” in any form—the paying of coaches, the recruiting and subsidizing of athletes, the commercializing of the supposedly amateur game—violated the sport's purported principles, yet it was also at the heart of the popular spectacle staged in the enormous stadiums before as many as 120,000 spectators. College football was regularly attacked in intellectual journals, but the routine celebration of the game in the daily and weekly coverage of the popular media drowned out any criticism. A report by the Carnegie Foundation in 1929 documenting professionalism at 84 of 112 institutions troubled many college administrators but was generally shrugged off by the public and the sportswriters who fed its passion for the game.

The 1920s saw the emergence of Red Grange (Grange, Red) as football's first true celebrity. Grange received national acclaim for his brilliant performances in games against Michigan and Pennsylvania, but he also created the sport's greatest controversy since the 1906 rule changes when he left the University of Illinois (without graduating) to join the Chicago Bears of the professional National Football League. “Professionalism” in any form—the paying of coaches, the recruiting and subsidizing of athletes, the commercializing of the supposedly amateur game—violated the sport's purported principles, yet it was also at the heart of the popular spectacle staged in the enormous stadiums before as many as 120,000 spectators. College football was regularly attacked in intellectual journals, but the routine celebration of the game in the daily and weekly coverage of the popular media drowned out any criticism. A report by the Carnegie Foundation in 1929 documenting professionalism at 84 of 112 institutions troubled many college administrators but was generally shrugged off by the public and the sportswriters who fed its passion for the game.Bowl games

In the 1920s and '30s colleges and universities throughout the Midwest, South, and West, in alliance with local civic and business elites, launched campaigns to gain national recognition and economic growth through their football teams. They organized regional conferences—the Big Ten and the Big 6 (now the Big 12) in the Midwest; the Southern, Southeastern, and Southwest conferences in the South; and the Pacific Coast Conference in the West—and scheduled “intersectional” games with regional prestige at stake. The Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California, on New Year's Day, first contested in 1902 between Stanford (Stanford University) and Michigan, then annually beginning in 1916, determined an unofficial national champion and was also a highly profitable commercial enterprise. Promoters in other Sun Belt cities developed rival bowl games—the Orange Bowl in Miami (1933), the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans (1935), and the Cotton Bowl in Dallas (1937)—eventually to be joined by so many others that the NCAA in the 1950s began to regulate them.

Knute Rockne (Rockne, Knute) and the influence of coaches

A distinguishing mark of American football is the renown and status granted to the most successful and innovative coaches. The first innovators were men such as Walter Camp (not literally a coach but an adviser), Amos Alonzo Stagg (Stagg, Amos Alonzo) at the University of Chicago, George Woodruff at Pennsylvania, and Lorin Deland at Harvard, the coaches who developed the V trick, ends back, tackles back, guards back, flying wedge, and other mass formations that revolutionized, and nearly destroyed, the game in the 1890s. The most influential of the early coaches was Pop Warner (Warner, Pop), whose wingback formations (the single wing and the double wing), developed at Carlisle, Pittsburgh, and Stanford, became the dominant offensive systems through the 1930s.

A distinguishing mark of American football is the renown and status granted to the most successful and innovative coaches. The first innovators were men such as Walter Camp (not literally a coach but an adviser), Amos Alonzo Stagg (Stagg, Amos Alonzo) at the University of Chicago, George Woodruff at Pennsylvania, and Lorin Deland at Harvard, the coaches who developed the V trick, ends back, tackles back, guards back, flying wedge, and other mass formations that revolutionized, and nearly destroyed, the game in the 1890s. The most influential of the early coaches was Pop Warner (Warner, Pop), whose wingback formations (the single wing and the double wing), developed at Carlisle, Pittsburgh, and Stanford, became the dominant offensive systems through the 1930s.The only rival to Pop Warner's wing formations in the 1920s and '30s was Knute Rockne (Rockne, Knute)'s Notre Dame box, his refinement of the shift from the T to a box-shaped formation that was first developed by Stagg. A series of rule changes eventually rendered the box shift ineffective, but Rockne, football's first celebrity coach, was less an innovator than a master teacher and motivator. Under his guidance, Notre Dame (Notre Dame, University of) developed the dominant football program in the country. Theirs was the only team of the era with a nationwide following and the benchmark against which others were measured, yet Rockne accomplished this under most unpromising circumstances. The 1920s were marked by anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant prejudice in much of the country, and Notre Dame's teams were decidedly Roman Catholic and ethnic. College football was transformed in the 1920s and '30s by the sons of Italian, Polish, Jewish, and other southern and eastern European immigrants, most conspicuously in the lineups of Catholic universities (Fordham, St. Mary's, and more than a dozen others in addition to Notre Dame) and the state universities in Pennsylvania and the upper Midwest. Known as the Ramblers or the Nomads (the “Fighting Irish” nickname was adopted in the late 1920s), the Notre Dame team developed a national schedule out of necessity rather than design. Refused games by nearby Big Ten rivals, Rockne scheduled contests with Army, Georgia Tech, Southern California, Southern Methodist, Nebraska—an entire intersectional schedule rather than a key game or two. The university's administrators soon recognized the advantages to be had, as Notre Dame became the representative school for Catholics and new immigrants throughout the country. In an era of university-building through big-time football, Notre Dame became the model that many others sought to emulate.

Initially the paying of coaches was controversial, as yet another mark of professionalism in the amateur sport, and there was always resistance to coaches' increasing control over the game. Rules to prevent “sideline coaching”—sending in plays from the sidelines—were first established in 1892 and not abandoned altogether until 1967. After free substitution was permitted during World War II because of the wartime manpower shortage, a postwar controversy over one-platoon or two-platoon football (11 men playing both ways, or separate squads for offense and defense) arose in part out of concern that coaches not gain more control over the game. The colleges returned to one-platoon football in 1953, but in 1965 open substitution and two platoons returned to stay, and coaches soon took over all of the play calling. Successful coaches were well compensated, often earning more than full professors by the 1920s (a time when such disparities were controversial) and eventually more than college presidents; this trend culminated in the million-dollar—and even two-million-dollar—salaries of the 21st century.

Birth and early growth of professional football

As college football thrived, professional football struggled for respectability. The group of teams that became the National Football League (NFL) was organized in 1920 as the American Professional Football Association (changing its name in 1922), with Jim Thorpe (Thorpe, Jim) as its nominal president. Former (and sometimes current) college stars had played for money since 1892, initially for athletic clubs in western Pennsylvania, then for the openly professional teams that were formed in mostly small towns in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois. In its first season, in 1920, the APFA had 14 teams, including George Halas (Halas, George)'s Decatur (Illinois) Staleys, who in 1922 became the Chicago Bears, the NFL's dominant team for much of its formative period. Joe Carr, an experienced promoter, succeeded Thorpe as president in 1921 and remained in that position until his death in 1939. Over the 1920s and early 1930s, league membership fluctuated between 8 and 22 teams, the majority not in large cities but in towns such as Akron, Canton, Dayton, and Massillon, all in Ohio; Racine, Wisconsin; and Rockford, Illinois. With professionalism widely regarded as the greatest danger to college football, professional football was little more respectable than professional wrestling. Red Granges' turning professional in 1925 provided a temporary boost to the professional game, but interest in professional football could be sustained only in those communities with franchises.

As college football thrived, professional football struggled for respectability. The group of teams that became the National Football League (NFL) was organized in 1920 as the American Professional Football Association (changing its name in 1922), with Jim Thorpe (Thorpe, Jim) as its nominal president. Former (and sometimes current) college stars had played for money since 1892, initially for athletic clubs in western Pennsylvania, then for the openly professional teams that were formed in mostly small towns in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois. In its first season, in 1920, the APFA had 14 teams, including George Halas (Halas, George)'s Decatur (Illinois) Staleys, who in 1922 became the Chicago Bears, the NFL's dominant team for much of its formative period. Joe Carr, an experienced promoter, succeeded Thorpe as president in 1921 and remained in that position until his death in 1939. Over the 1920s and early 1930s, league membership fluctuated between 8 and 22 teams, the majority not in large cities but in towns such as Akron, Canton, Dayton, and Massillon, all in Ohio; Racine, Wisconsin; and Rockford, Illinois. With professionalism widely regarded as the greatest danger to college football, professional football was little more respectable than professional wrestling. Red Granges' turning professional in 1925 provided a temporary boost to the professional game, but interest in professional football could be sustained only in those communities with franchises. The NFL took its modern shape in 1933 under Carr's guidance, when it was reorganized in two five-team divisions of big-city clubs (with Green Bay the lone exception) whose leaders would meet at the end of the season for the NFL title. In the 1930s professional football was predominantly a working-class spectator sport. The preseason College All-Star Game, created by Chicago Tribune sports columnist Arch Ward in 1934 to pit the reigning NFL champion against a team of just-graduated collegians, helped break down the barrier between college and professional football. Over the 1930s and '40s the professional sport's popularity grew in NFL cities, particularly those such as New York without a major state university with which to compete for the community's loyalty. Minor professional leagues such as the American Association, Dixie League, and Pacific Coast Professional Football League had relatively modest local followings. The NFL was also successful enough to attract competitors. The American Football League was formed in 1926 by Grange and his agent, but it lasted just one year. A second (1936–37) and third (1940–41) AFL were also formed. Finally, the All-America Football Conference (1946–1949) seriously challenged the existing league and contributed the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and a first version of the Baltimore Colts (Indianapolis Colts) to an expanded NFL in 1950. Yet professional football could offer the public nothing comparable to the compelling rivalries, youthful enthusiasm, and colourful pageantry of college football. It was only in the 1950s with the arrival of television that professional football could reach beyond the franchise cities to become a national sport.

The NFL took its modern shape in 1933 under Carr's guidance, when it was reorganized in two five-team divisions of big-city clubs (with Green Bay the lone exception) whose leaders would meet at the end of the season for the NFL title. In the 1930s professional football was predominantly a working-class spectator sport. The preseason College All-Star Game, created by Chicago Tribune sports columnist Arch Ward in 1934 to pit the reigning NFL champion against a team of just-graduated collegians, helped break down the barrier between college and professional football. Over the 1930s and '40s the professional sport's popularity grew in NFL cities, particularly those such as New York without a major state university with which to compete for the community's loyalty. Minor professional leagues such as the American Association, Dixie League, and Pacific Coast Professional Football League had relatively modest local followings. The NFL was also successful enough to attract competitors. The American Football League was formed in 1926 by Grange and his agent, but it lasted just one year. A second (1936–37) and third (1940–41) AFL were also formed. Finally, the All-America Football Conference (1946–1949) seriously challenged the existing league and contributed the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and a first version of the Baltimore Colts (Indianapolis Colts) to an expanded NFL in 1950. Yet professional football could offer the public nothing comparable to the compelling rivalries, youthful enthusiasm, and colourful pageantry of college football. It was only in the 1950s with the arrival of television that professional football could reach beyond the franchise cities to become a national sport.Football for American youth

A fundamental aspect of football before the age of television was its local-rootedness. In the smallest towns, with no local college or professional team, community identity and pride were often invested in the high school team. In 1920, the year the predecessor of the NFL was organized, the forerunner of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFSHSA, later NFHS) was also formed, as the high school game was spreading throughout the country. Beginning in the 1930s, six-man and then eight-man versions made it possible for even the smallest rural schools to field teams.

Local passions for high school football varied widely, as certain communities became famous for investing in the schoolboy sport all of the intensity usually reserved for the big-time college game. The December playoff between the Catholic and public school champions in Chicago drew crowds as large as 120,000 in the 1930s, and states such as Ohio and Texas became renowned for their high school football passions. Youth leagues were also formed in most communities, some through elementary schools, others through local clubs, some of which were affiliated with national organizations such as the Catholic Youth Organization or Pop Warner Football. Concern about injuries was always an issue in youth football, but the game was widely assumed to be character-building. By the end of the 1930s, football had been established not just as an intercollegiate, interscholastic, and professional sport but also as a part of the very fabric of American life.

The racial transformation of American football

Through the end of World War II, very few African American athletes had an opportunity to play mainstream football at any level. A separate and decidedly unequal black football world first emerged in the 1890s as part of the larger expansion of college football. The first documented game between all-black colleges was played in 1892 in North Carolina between Biddle University and Livingston College. The first black college conferences, the Colored Intercollegiate Athletic Association and the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, were formed in 1912, followed by the Southwestern Athletic Conference in 1920 and the Midwestern Athletic Association in 1926. Black college football was woefully underfunded, but it had its own All-Americans (stars such as “Jazz” Byrd, Ben Stevenson, “Tarzan” Kendall, and “Big Train” Moody), its great rivalries (Howard-Lincoln, Tuskegee-Atlanta, Morgan-Hampton, Wiley-Prairie View), its own pageantry, and even its own scandals. All of this took place outside the consciousness of the mainstream football public but was thoroughly covered by a thriving black press.

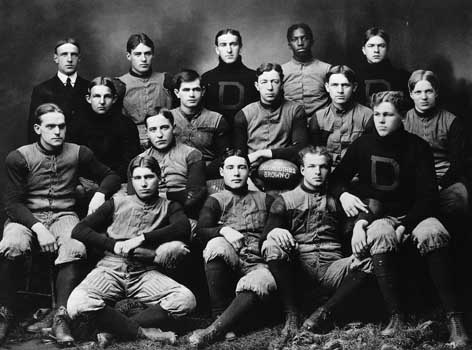

Mainstream football, however, was not altogether segregated (segregation, racial). William Henry Lewis and William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson were black teammates for Amherst College in 1889, and Lewis made Walter Camp's All-America team in 1892 after he had moved to Harvard to play football while attending law school (he later became an assistant U.S. attorney general). A handful of black players were always part of big-time college football, and some—including Lewis, Fritz Pollard (Pollard, Fritz) at Brown, Paul Robeson (Robeson, Paul) at Rutgers, and Duke Slater at Iowa—were among the early game's greatest stars. Yet, until 1939, when UCLA fielded a team that included Jackie Robinson (Robinson, Jackie), Kenny Washington (Washington, Kenny), and two other black teammates, no college had more than one or two black players, and most continued to have none.

Mainstream football, however, was not altogether segregated (segregation, racial). William Henry Lewis and William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson were black teammates for Amherst College in 1889, and Lewis made Walter Camp's All-America team in 1892 after he had moved to Harvard to play football while attending law school (he later became an assistant U.S. attorney general). A handful of black players were always part of big-time college football, and some—including Lewis, Fritz Pollard (Pollard, Fritz) at Brown, Paul Robeson (Robeson, Paul) at Rutgers, and Duke Slater at Iowa—were among the early game's greatest stars. Yet, until 1939, when UCLA fielded a team that included Jackie Robinson (Robinson, Jackie), Kenny Washington (Washington, Kenny), and two other black teammates, no college had more than one or two black players, and most continued to have none.The routine indignities facing the black pioneers on predominantly white teams and campuses became compounded when intersectional games were scheduled between segregated Southern (South, the) schools and marginally integrated Northern ones. Typically, the Northern school agreed to “bench” its one or two black players so as not to offend Southern sensibilities. Such incidents occasionally aroused local protest from progressive student groups and were thoroughly covered in the black press, but they went largely unreported in the mainstream media. By the late 1930s the typical arrangement was to hold out the black players for games played in the segregated South but to allow them to play at home, an accommodation that continued into the 1950s. The first integrated college football game in the South took place in 1947 between Virginia and Harvard, whose Chester Pierce was permitted to play. Many Northern schools solved the problem simply by not scheduling teams from the South, and bowl games likewise avoided racial incidents by matching up only Southern teams. The Cotton Bowl was integrated, without incident, in 1948, the Orange Bowl in 1955. The Sugar Bowl was integrated by the University of Pittsburgh's Bobby Grier in 1956, only after Georgia's segregationist governor, Marvin Griffin, backed down from threats to keep Georgia Tech from playing. The integration of Southern college teams progressed gradually over the postwar years. The Big 6 conference was integrated in 1947 and the Missouri Valley Conference in 1950; but the Atlantic Coast Conference did not begin integrating until 1963, the Southwest Conference until 1966, and the Southeastern Conference until 1967.

The NFL had been integrated at the beginning, with Fritz Pollard among the league's first stars and some 13 African American players hired between 1920 and 1933. Between 1934 and 1945, however, a “gentleman's agreement,” apparently at the instigation of George Preston Marshall, owner of the Boston (later Washington) Redskins (Washington Redskins), kept the NFL all-white. The reintegration of professional football began in 1946—in the NFL, where the Rams risked losing their lease on the Los Angeles Coliseum if they did not sign Kenny Washington (the Rams signed Woody Strode as well, to give Washington a black roommate); and in the rival All-America Football Conference, where coach Paul Brown (Brown, Paul) immediately signed Bill Willis and Marion Motley (Motley, Marion) for his Cleveland Browns—and it was completed in 1962, when Marshall signed Bobby Mitchell to play for the Redskins. The first generation of black NFL stars came almost exclusively from the mainstream football world, but in the 1960s NFL scouts discovered the black colleges, Eddie Robinson (Robinson, Eddie)'s Grambling Tigers in particular. This golden era for black college football was short-lived, however, as integration ended the black colleges' monopoly on local African American athletic talent.

The NFL had been integrated at the beginning, with Fritz Pollard among the league's first stars and some 13 African American players hired between 1920 and 1933. Between 1934 and 1945, however, a “gentleman's agreement,” apparently at the instigation of George Preston Marshall, owner of the Boston (later Washington) Redskins (Washington Redskins), kept the NFL all-white. The reintegration of professional football began in 1946—in the NFL, where the Rams risked losing their lease on the Los Angeles Coliseum if they did not sign Kenny Washington (the Rams signed Woody Strode as well, to give Washington a black roommate); and in the rival All-America Football Conference, where coach Paul Brown (Brown, Paul) immediately signed Bill Willis and Marion Motley (Motley, Marion) for his Cleveland Browns—and it was completed in 1962, when Marshall signed Bobby Mitchell to play for the Redskins. The first generation of black NFL stars came almost exclusively from the mainstream football world, but in the 1960s NFL scouts discovered the black colleges, Eddie Robinson (Robinson, Eddie)'s Grambling Tigers in particular. This golden era for black college football was short-lived, however, as integration ended the black colleges' monopoly on local African American athletic talent.The era of television

Together with the racial integration of the game at all levels, the coming of television in the 1950s marked a new era in the development of American football. The 1950s were a boom time for professional football but a bad time for the colleges, yet intercollegiate football, too, emerged from the decade not only intact but on the verge of unprecedented prosperity.

Immediately following World War II, college football experienced a surge in popularity, but attendance declined by the end of the decade and recovered very slowly over the 1950s. Many colleges dropped the game as too expensive, including one-time powers such as Fordham and St. Mary's. The informally organized Ivy League became a formal organization in 1954, choosing to play a “deemphasized” brand of football. The National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball, created in 1940 by small colleges concerned about the state of amateurism in that sport, became the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) in 1952 and first sponsored a national championship in football in 1956.

The colleges and universities that clung to the big-time game faced a double crisis: the impact of television on gate receipts and the final throes of the ongoing controversy over professionalism. The NCAA named its first executive director, Walter Byers, in 1951 (he continued in that role until 1987) and took on regulatory and enforcement powers for the first time. Regarding television not as the tremendous source of revenue it eventually became but as the most serious threat to gate receipts, the NCAA in 1951 assumed control of broadcasting rights and established severe restrictions on the number of times any team could appear on TV. Under NCAA control, while attendance grew from 20 million in 1961 to 35.8 million in 1981, TV revenues increased from $3 million to $31 million, then doubled in 1982 when the NCAA signed its final contract with the networks.

Divvying up these huge revenues nearly tore the NCAA apart—small schools sought a portion for themselves, while the major football powers resented sharing the income that they generated. The big schools also chafed as NCAA decision making was dominated by the more numerous smaller schools. University and college divisions were created within the NCAA in 1968, with 223 schools in the former and 386 in the latter; then, at a special meeting in 1973, institutions were assigned to Divisions I, II, or III, based essentially on the size and ambitions of the football program. Subsequent conventions fought over the allocation of TV revenues among the divisions, and in 1977 the major football conferences (excluding only the Pacific-8 and the Big Ten), along with the major independents such as Notre Dame, formed the College Football Association (CFA) to challenge the NCAA's power. Faced with the threat of the CFA, the NCAA at its 1978 convention split Division I into Division I-A (the big-time football schools) and I-AA.

Still unsatisfied by the division of TV revenues under the new arrangement, the CFA attempted to negotiate its own TV contract in 1981. When the NCAA threatened sanctions, the Universities of Georgia and Oklahoma sued the organization for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act; the University of Texas sued separately. By 1984 the plaintiffs had prevailed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the NCAA no longer controlled TV contracts. The CFA itself was undermined in 1990 when Notre Dame broke ranks to sign its own contract with NBC, after which individual conferences began negotiating separate arrangements with the networks.

As a consequence of these varied actions, by the 1990s television revenues were going almost entirely to the big football schools, and major conference realignments—Penn State joining the Big Ten in 1990, the Southeastern Conference expanding to 12 teams in 1992, the Big 8 becoming the Big 12 in 1996 by absorbing four Texas schools from the disbanded Southwest Conference—resulted in large part from consideration of TV markets.

Scholarships and the student athlete

College football's other post-World War II crisis, regarding professionalism, reached a flash point in the late 1940s and early 1950s over athletic scholarships. Subsidizing athletes had been common since the 1920s but was not officially sanctioned and was entirely unregulated, controlled more often by alumni than by athletic departments. When the NCAA took on the issue after World War II, the Big Ten and the Pacific Coast Conference lobbied for need-based scholarships which awarded on-campus jobs. The Southeastern and Southwest conferences led the campaign for open athletic scholarships, declaring the job plan merely hypocritical (entailing phony jobs that required no work). The job plan bloc prevailed at the NCAA convention in January 1948, passing what became known as the Sanity Code, but battles at subsequent meetings led to its being rescinded at the 1951 convention, and the now-familiar athletic grant-in-aid was finally adopted in 1957. Also in 1951, most of Army (United States Military Academy)'s football team was dismissed for cheating on exams; and it had been revealed earlier in the year that basketball players at several major universities had accepted money from gamblers to shave points. Out of this morass of scandal, the NCAA emerged stronger than ever, solidifying its standing as the regulatory, investigative, and punitive organization that ruled collegiate sports.

Once the issue of financial support was resolved and the sport fully integrated, the players' status as student-athletes received sharper scrutiny. The NCAA first tied eligibility for athletic scholarships to academic success in high school in 1965 with its “1.6 rule,” then replaced it with a 2.0 grade-point-average standard in 1973. When the group passed Proposition 48 in 1983, followed by Proposition 16 in 1992, which together set minimal grade-point averages in a high school core curriculum and scores on the Scholastic Aptitude Test for scholarships and freshman eligibility, it addressed one continuing controversy while provoking another—its disproportionate impact on African Americans.

The problems and convulsions of the larger society inevitably spilled over into college football. The racial turmoil of the late 1960s led to bitter confrontations between black players and white coaches at several universities, and drug problems arose periodically, ranging from the abuse of amphetamines in the 1970s to the more dangerous abuse of anabolic steroids in the 1980s. The passage of Title IX forced athletic departments to divert financial resources into sports for women as well as men and made the football team, with its huge number of scholarships but also its unique capacity to generate income, a focal point for debates over gender equity. The commercialization set in motion by television led to institutional partnerships with soft drink and shoe companies, corporate sponsorship of bowl games, and million-dollar contracts for football coaches who were expected to contend for national championships. The competing demands of the sport, as an extracurricular activity for student-athletes and as mass entertainment, remained at the heart of American college football at the turn of the 21st century.

Bowl games and the national championship

Even as bowl games proliferated in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, controversies shadowed them—for their commercialization of the amateur sport and prolonging of the season at the expense of academics—but resistance disappeared when the financial windfall from the televised contests became a major source of revenue for the top teams and conferences. A new controversy emerged in the 1970s, however, regarding the bowls' inability to produce an unambiguous national champion. A perennial call for a national championship playoff, resisted by defenders of the traditional bowl games, eventually prompted the creation in 1992 of the Bowl Coalition—involving four major bowl games (Cotton, Fiesta (Fiesta Bowl), Orange, and Sugar), five major conferences (excluding the Big Ten and Pac-10), and independent Notre Dame—with the goal of matching the two top-rated teams in a championship game that would rotate among the four bowls. In 1995 the Bowl Coalition was replaced by the Bowl Alliance (involving six conferences, Notre Dame, and only three bowls), but the nonparticipation of the Rose Bowl, Big Ten, and Pac-10 continued to leave the scheme badly flawed. In 1998 the Rose Bowl and its two participating conferences joined the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) (BCS), which included all the major teams and conferences, with a supposed national championship game now rotating among the Rose, Orange, Sugar, and Fiesta bowls. The matching of the University of Nebraska with Miami in the 2002 Rose Bowl, however, after Nebraska had failed to win its own conference championship, made it clear that the BCS had not yet resolved the issue and guaranteed that a debate over a playoff along the lines of the NCAA basketball tournament would continue.

Even as bowl games proliferated in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, controversies shadowed them—for their commercialization of the amateur sport and prolonging of the season at the expense of academics—but resistance disappeared when the financial windfall from the televised contests became a major source of revenue for the top teams and conferences. A new controversy emerged in the 1970s, however, regarding the bowls' inability to produce an unambiguous national champion. A perennial call for a national championship playoff, resisted by defenders of the traditional bowl games, eventually prompted the creation in 1992 of the Bowl Coalition—involving four major bowl games (Cotton, Fiesta (Fiesta Bowl), Orange, and Sugar), five major conferences (excluding the Big Ten and Pac-10), and independent Notre Dame—with the goal of matching the two top-rated teams in a championship game that would rotate among the four bowls. In 1995 the Bowl Coalition was replaced by the Bowl Alliance (involving six conferences, Notre Dame, and only three bowls), but the nonparticipation of the Rose Bowl, Big Ten, and Pac-10 continued to leave the scheme badly flawed. In 1998 the Rose Bowl and its two participating conferences joined the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) (BCS), which included all the major teams and conferences, with a supposed national championship game now rotating among the Rose, Orange, Sugar, and Fiesta bowls. The matching of the University of Nebraska with Miami in the 2002 Rose Bowl, however, after Nebraska had failed to win its own conference championship, made it clear that the BCS had not yet resolved the issue and guaranteed that a debate over a playoff along the lines of the NCAA basketball tournament would continue.Ascendance of the NFL

Connected to a national audience through television—and under no obligation to build character or maintain educational standards—professional football became the most spectacular success story in the world of American sport over the second half of the 20th century. To an even greater degree than for college football, television became the professional sport's lifeblood, with increasingly lucrative television contracts guaranteeing large profits for every club no matter how well it fared on the field. In the 1950s, while college authorities fretted over television, NFL commissioner Bert Bell embraced it immediately and won congressional approval to black out television coverage in the cities where home teams were playing. In a stroke, Bell's efforts assured maximum attendance for the league's 12 clubs with little impact on the size of the league's rapidly growing TV audience.

The televised championship game between the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants in 1958, decided in sudden death overtime, is widely recognized as the turning point in professional football's embrace by a national audience. When Bell died in 1959, he was succeeded by the general manager of the Los Angeles Rams, Pete Rozelle (Rozelle, Pete), who became the most powerful and most effective commissioner in American professional sports. In addition to creating NFL Properties, which became a multibillion-dollar enterprise, Rozelle negotiated a series of contracts with the TV networks that grew from $4.65 million for the 1962 season to nearly $500 million per year when he retired in 1989, guaranteeing more than $17 million per club before a single fan bought a ticket. Most crucially, Rozelle persuaded Congress to continue granting the NFL exemptions from the Sherman Antitrust Act, allowing franchises to operate not as individual businesses but as a single entity, each club sharing equally in league-generated revenues. Under Rozelle, the value of franchises increased from about $1 million in 1960 to more than $100 million in 1989, and under the structure he put in place franchise values exceeded $500 million by the end of the 20th century.

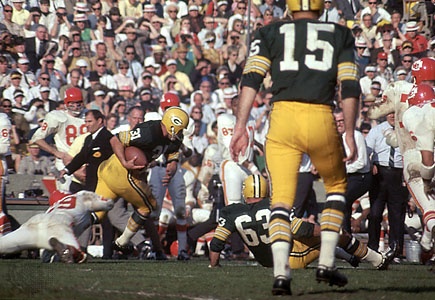

The NFL faced competition from a new rival in 1960, when the American Football League (AFL), backed by Texas billionaire Lamar Hunt, fielded teams in eight cities, three of them in direct competition with NFL franchises. A television contract with NBC gave the AFL a financial security none of its predecessors had had, and the NFL and AFL agreed to a merger in 1966, completed in 1970 with 26 clubs in two conferences. The pass-oriented AFL brought more excitement to professional football, as well as the game's most glamorous player, the New York Jets' quarterback Joe Namath (Namath, Joe). Out of the merger also came the Super Bowl, which soon became the single most popular and lucrative of all sporting events in the United States. Super Bowl I (not yet with that name) was played between the Green Bay Packers and the Kansas City Chiefs after the 1966 season, with more than 40 percent of the country's television sets tuned in to the two networks that broadcast the game. That percentage never dropped lower than 36, and it nearly hit 50 in 1982, as the game was eventually watched by as many as 130 million Americans in addition to a worldwide audience. The Super Bowl became a major civic ritual, as famous for its surrounding hoopla and million-dollar commercials as for the football games.

The NFL faced competition from a new rival in 1960, when the American Football League (AFL), backed by Texas billionaire Lamar Hunt, fielded teams in eight cities, three of them in direct competition with NFL franchises. A television contract with NBC gave the AFL a financial security none of its predecessors had had, and the NFL and AFL agreed to a merger in 1966, completed in 1970 with 26 clubs in two conferences. The pass-oriented AFL brought more excitement to professional football, as well as the game's most glamorous player, the New York Jets' quarterback Joe Namath (Namath, Joe). Out of the merger also came the Super Bowl, which soon became the single most popular and lucrative of all sporting events in the United States. Super Bowl I (not yet with that name) was played between the Green Bay Packers and the Kansas City Chiefs after the 1966 season, with more than 40 percent of the country's television sets tuned in to the two networks that broadcast the game. That percentage never dropped lower than 36, and it nearly hit 50 in 1982, as the game was eventually watched by as many as 130 million Americans in addition to a worldwide audience. The Super Bowl became a major civic ritual, as famous for its surrounding hoopla and million-dollar commercials as for the football games.Showmanship on the field

Constant innovation held fan interest and kept it steadily increasing. Polls beginning in the early 1970s repeatedly identified professional football as Americans' favourite sport. Over the 1970s and '80s the NFL withstood the challenge of new rival leagues—the World Football League (1974–75) and the United States Football League (1983–85)—and invested in Arena Football (an indoor version of the sport, played in the NFL's off-season beginning in 1987) and expanded into Europe in 1991 with the World League of American Football (later NFL Europe). The African American athletes who increasingly dominated football also brought a new style to the game. The beginnings of end zone dances in the 1970s escalated into highly choreographed routines, followed by other attention-grabbing gestures by defensive as well as offensive players. These displays eventually led to rules against “excessive celebration” (in the NCAA as well as the NFL) and countercharges by African American spokesmen that the banned actions and gestures were not failures of sportsmanship but African American self-expression. Fans were divided between enjoyment of the antics and criticism for the loss of old-fashioned values, but the new flamboyance played well on television, and it made football more than ever an arena in which Americans dealt with shifting attitudes about race.

Franchise shifts and free agency

The two events most responsible for shaping the NFL for the 21st century took place off the field: a series of legal decisions established free agency for players and gave owners greater freedom to move their franchises. The growth of television revenues inevitably led the players to demand a fair share of the profits. In 1970 a brief training-camp strike by the NFL Players Association (formed in 1956 but relatively inactive until the 1970s) caused no disruption of the football season but foreshadowed more serious labor-management disputes to come. In 1974 a 41-day strike during training camp affected only preseason games, as the Players Association capitulated. More serious and prolonged strikes in 1982 (when the players were locked out for 57 days and the season was reduced to nine games) and 1987 (when a strike lasted 24 days, leading owners to cancel one game and hire “replacement” players for three more) were equally unsuccessful from the players' perspective but far more damaging to the image of the league.

A full quarter of the league's veteran players crossed picket lines in 1974, and in 1982 and 1987 those who refused to strike or who criticized the union included some of the game's top players. What the players lost on the picket line they won in court, however, as a series of lawsuits finally forced the owners in 1993 to agree to free agency, with a salary cap (a limit on each club's expenditures on salaries). With players now able to change teams, salaries increased dramatically (from an average of $490,000 in 1992 to $663,000 in 1993, then reaching $1,120,000 by 2002), yet the clubs' financial stability and the competitive balance among teams were preserved by the salary cap and the college draft, which the Players Association made no attempt to challenge.

The NFL's other defeat in court benefited individual owners. In 1980 Al Davis, the managing general partner of the Oakland Raiders, successfully sued the NFL for not allowing him to move the Raiders to Los Angeles, where he expected to make considerably more money (after leaving in 1982, Davis returned the Raiders to Oakland in 1995). The freedom to move franchises without league approval gave owners a powerful position in negotiating with city governments that viewed an NFL franchise as an essential foundation of community pride and the local economy. Numerous franchise shifts in the 1980s and '90s provoked local outrage but did not damage the league. At the turn of the 21st century, professional football was without question the most popular and the most profitable of American sports.

Tactical developments

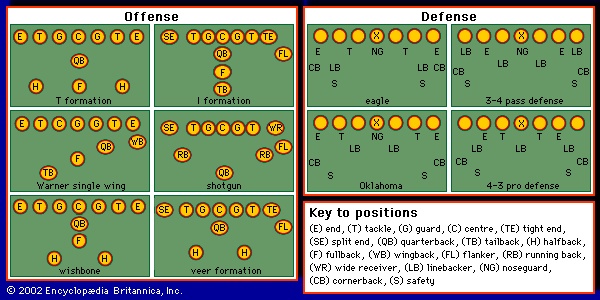

The play on the field underwent continual innovation. Lacking the cachet of “college spirit,” the NFL since the 1930s had always placed greater importance on entertainment. The NFL formed its own rules committee in 1933 and immediately moved the goal posts to the goal line (to make field goals easier), liberalized the rules on passing, and spotted the ball 10 yards from the sidelines when it went out of bounds. (Until that time, the ball was placed at the sideline, and a play had to be wasted in order to move it to closer to the middle of the field.) Subsequent changes, in 1935 and 1972, eventually placed the ball even with the goal posts (the colleges made similar changes but settled on a “hash mark” one-third of the field's width). As the new rules opened up play, the Chicago Bears under coaches George Halas (Halas, George) and Ralph Jones, assisted by University of Chicago coach Clark Shaughnessy (Shaughnessy, Clark Daniel), reintroduced the old T formation, which eventually replaced the single wing as the dominant offensive formation. Quarterback Sammy Baugh (Baugh, Sammy) and receiver Don Hutson (Hutson, Don) elevated the passing game to new levels, while most college teams still played in a lower-scoring conservative style.

In the 1950s the Los Angeles Rams' head coach Sid Gillman exploited the passing game as never before, but in the late 1940s and '50s it was the Cleveland Browns' head coach Paul Brown (Brown, Paul) who revolutionized professional football with organizational principles that were eventually adopted throughout the football world. Brown made the watching of game films a part of the entire team's preparation, placed assistant coaches in the press box, even experimented with implanting a radio transmitter in the quarterback's helmet—a tactic quickly banned by the commissioner, not to be legalized for another four decades. Brown invented “pocket protection” for his quarterback, with the linemen not aggressively blocking, as on running plays, but dropping back into a pocket to shield the quarterback. Vince Lombardi (Lombardi, Vince) extended this principle to running plays at Green Bay in the 1960s, having his linemen block areas rather than specific men and having the running back read which way his lineman blocked his man at the point of attack. The basic principle of brushing defensemen aside rather than overpowering them gave new flexibility to the running game.

College football gradually adjusted to the more pass-oriented professional style, and college and professional coaches after World War II borrowed from each other, always looking for ways to exploit an offensive or defensive advantage. The Southwest Conference had been known for its wide-open passing attacks in the 1930s, but college football remained fundamentally a power running game into the 1980s. College coaches' most distinctive innovations in the 1970s and '80s came in offenses that featured running quarterbacks—the triple-option schemes such as the wishbone and veer (with the quarterback handing the ball off to a fullback, pitching it to a tailback, or keeping it himself), offenses that were unattractive to the pros because they put quarterbacks at physical risk.

The original defenses had simply mirrored the positions of the offense. In the 1930s a 6-2-2-1 alignment became dominant (6 linemen, 2 linebackers, 2 cornerbacks, and 1 safety). In the NFL, to stop the increased passing that came with the T formation in the 1940s, the Philadelphia Eagles' Greasy Neale developed the 5-3-2-1 defense, which was in turn replaced in the mid-1950s by the 4-3 (actually 4-3-2-2) perfected by Tom Landry (Landry, Tom) as an assistant coach with the New York Giants. In this alignment the defensive tackles kept blockers off the middle linebacker, who became the dominant defensive player. The 4-3 defense made stars of such middle linebackers as Sam Huff, Joe Schmidt, Ray Nitschke, Dick Butkus (Butkus, Dick), and Willie Lanier (Lanier, Willie). The 4-3, in turn, yielded to the 3-4 in the mid-1970s, moving the emphasis to outside linebackers rather than the middle linebacker. The New York Giants' Lawrence Taylor (Taylor, Lawrence) became the prototype outside linebacker in the 1980s, with tremendous speed to cover receivers and tremendous power to rush the quarterback.

The original defenses had simply mirrored the positions of the offense. In the 1930s a 6-2-2-1 alignment became dominant (6 linemen, 2 linebackers, 2 cornerbacks, and 1 safety). In the NFL, to stop the increased passing that came with the T formation in the 1940s, the Philadelphia Eagles' Greasy Neale developed the 5-3-2-1 defense, which was in turn replaced in the mid-1950s by the 4-3 (actually 4-3-2-2) perfected by Tom Landry (Landry, Tom) as an assistant coach with the New York Giants. In this alignment the defensive tackles kept blockers off the middle linebacker, who became the dominant defensive player. The 4-3 defense made stars of such middle linebackers as Sam Huff, Joe Schmidt, Ray Nitschke, Dick Butkus (Butkus, Dick), and Willie Lanier (Lanier, Willie). The 4-3, in turn, yielded to the 3-4 in the mid-1970s, moving the emphasis to outside linebackers rather than the middle linebacker. The New York Giants' Lawrence Taylor (Taylor, Lawrence) became the prototype outside linebacker in the 1980s, with tremendous speed to cover receivers and tremendous power to rush the quarterback.

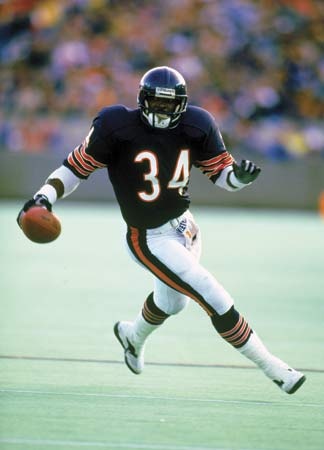

Pass defenses had always been either man-to-man or zone (each back covering an area). In the 1970s, when zone defenses virtually eliminated long passes, strong running games—featuring backs such as Buffalo's O.J. Simpson (Simpson, O.J.), Miami's Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick, and Pittsburgh's Franco Harris and Rocky Bleir—dominated the NFL. Landmark rule changes in 1977—banning defensive contact with wide receivers more than five yards downfield and allowing offensive linemen to block with their open hands—returned the advantage to the passing offenses. Small, quick offensive linemen gradually disappeared, replaced by 300-pound (140-kg) hulks who could hold off charging pass rushers with their extended arms and hands. (There were eight 300-pounders in the NFL in 1986 and 179 in 1996). Led by the so-called West Coast offense developed by Bill Walsh (Walsh, Bill) for the San Francisco 49ers, the passing game flourished as never before (in 1980 there were more passing than running plays for the first time since 1969). Other coaches developed run-and-shoot offenses, no-huddle offenses, and one-back offenses (with four wide receivers and no tight ends). Defensive coaches responded with “combo” pass defenses (combinations of zone and man-to-man), and the cornerback who could dominate a wide receiver by himself (Deion Sanders became the prototype) emerged as a new star. Running attacks increasingly featured a single back, making stars of such players as Tony Dorsett, Eric Dickerson, Walter Payton (Payton, Walter), Barry Sanders (Sanders, Barry), and Emmitt Smith (Smith, Emmitt).

Pass defenses had always been either man-to-man or zone (each back covering an area). In the 1970s, when zone defenses virtually eliminated long passes, strong running games—featuring backs such as Buffalo's O.J. Simpson (Simpson, O.J.), Miami's Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick, and Pittsburgh's Franco Harris and Rocky Bleir—dominated the NFL. Landmark rule changes in 1977—banning defensive contact with wide receivers more than five yards downfield and allowing offensive linemen to block with their open hands—returned the advantage to the passing offenses. Small, quick offensive linemen gradually disappeared, replaced by 300-pound (140-kg) hulks who could hold off charging pass rushers with their extended arms and hands. (There were eight 300-pounders in the NFL in 1986 and 179 in 1996). Led by the so-called West Coast offense developed by Bill Walsh (Walsh, Bill) for the San Francisco 49ers, the passing game flourished as never before (in 1980 there were more passing than running plays for the first time since 1969). Other coaches developed run-and-shoot offenses, no-huddle offenses, and one-back offenses (with four wide receivers and no tight ends). Defensive coaches responded with “combo” pass defenses (combinations of zone and man-to-man), and the cornerback who could dominate a wide receiver by himself (Deion Sanders became the prototype) emerged as a new star. Running attacks increasingly featured a single back, making stars of such players as Tony Dorsett, Eric Dickerson, Walter Payton (Payton, Walter), Barry Sanders (Sanders, Barry), and Emmitt Smith (Smith, Emmitt).More so at the professional than the college level, football became increasingly specialized. To the kicking specialists who emerged in the 1960s were later added extra blockers for goal-line offenses, extra defensive backs for expected passing plays, and then a variety of offensive and defensive specialists for the multiple alignments that all teams employed in the 1980s and '90s.

Football in Canada

The gridiron football played in Canada closely resembles the U.S. game, but it developed independently, and, overshadowed by ice hockey, it never achieved equal national importance.

The gridiron football played in Canada closely resembles the U.S. game, but it developed independently, and, overshadowed by ice hockey, it never achieved equal national importance.Canadian football's earliest history remains uncertain. It is generally agreed that rugby came to Canada with British soldiers early in the 19th century, and games were reported in the Toronto Globe as early as 1859. Students at the University of Toronto were playing football by the early 1860s, but it was clubs in Quebec and Ontario, rather than universities as in the United States, that led the way in developing the sport. Several of these clubs formed the Foot Ball Association of Canada in 1873, adopting Rugby Union rules in 1875. This initial association collapsed in 1877, to be followed by the first of the Canadian Rugby Football Unions in 1880; the final one, the Canadian Rugby Union (CRU), formed in 1891. Provincial unions were likewise formed in Ontario and Quebec in 1883, but football developed later in the West, with the Western Canadian Rugby Football Union not forming until 1911. The top senior clubs—the Big Four of Quebec and Ontario (Ottawa, Montreal, Hamilton, and Toronto), together with the five top Western clubs (Winnipeg, Saskatchewan, Calgary, Edmonton, and British Columbia)—eventually formed the major football organization in Canada, the professional Canadian Football League.

The Grey Cup, named for Governor-General Earl Grey, was first awarded in 1909, with college and club teams alike competing. Over time, the Grey Cup became Canada's professional championship, as well as a weeklong festival and the premier single sporting event in the country.

The CRU became the umbrella organization for all the football unions, including the Canadian Intercollegiate Rugby Football Union, which was formed by eight universities in 1897 in reaction to the growing professionalism among the top senior clubs. In addition to the championship for senior clubs, the CRU sponsored an intermediate championship beginning in 1894 and a junior championship beginning in 1908.

No clear boundaries between intercollegiate and club football, or even amateur and professional, were drawn in Canada for several decades, nor were football's commercial possibilities realized for some time. Unlike U.S. football, early Canadian football was a game for the players rather than the spectators. The University of Toronto's victory over the Parkdale Canoe Club for the initial Grey Cup, for example, drew 3,807 fans and generated gross revenues of $2,616.40—at a time when top U.S. university teams were playing before 50,000 spectators and Yale was earning more than $1 million from football.

Developing a uniform set of rules in Canada was far more difficult than in the United States. The U.S. model was a powerful influence that was resisted by those who desired to preserve the Canadian-ness of Canadian football. Though clinging to certain rugby features, the Canadian game was gradually "Americanized" by U.S. coaches such as Frank ("Shag") Shaughnessy at McGill University (1912–29) and by pressure from Western clubs, which were more open to U.S. influence and to professionalism. The legalization of the forward pass in 1931 led clubs, particularly in the West, to seek U.S. players skilled at the passing game, to whom was offered local employment in the midst of the Great Depression rather than direct payments.

An openly professional league, along the lines of the NFL, was first discussed in the 1930s, but it did not become a reality until after World War II. In 1935 the first-ever Western victory for the Grey Cup, by a Winnipeg club with nine U.S. players on the roster, marked a major turning point. The eastern-dominated CRU responded by establishing a residency requirement for players and limiting "imports" to five. The limit was raised from five to seven in 1950, then to eight in 1952, nine in 1954, and eventually 16. The top clubs formed their own Canadian Football Council (CFC) in 1956, dropping the name rugby altogether. The CFC became the Canadian Football League (CFL) in 1958 and withdrew from the CRU, with the four privately owned eastern clubs becoming the Eastern Football Conference in 1959 and the five community-run Western clubs becoming the Western Football Conference in 1961.

With the creation of the CFL, Canadian football at last took its modern form, with clearly differentiated professional and amateur versions. The CRU changed its name to the Canadian Amateur Football Association (CAFA) in 1966, when it also turned over trusteeship of the Grey Cup to the CFL; since 1986 CAFA has been known as Football Canada. As senior club football outside the CFL declined, the intercollegiate game, at a level comparable to (nonscholarship) Division III in the United States, became the chief amateur version. Provincial and regional intercollegiate athletic unions joined in a reconstituted Canadian Interuniversity Athletic Union (CIAU) in 1961 and changed its name to Canadian Interuniversity Sport (CIS) in 2001. Since 1967, conference champions have competed for the Vanier Cup in an annual Canadian College Bowl.

The CFL experienced a period of growth and relative stability in the 1970s and early 1980s, reaching an attendance record of 2,856,031 in 1983. Average salaries likewise increased, from $16,072 for imports and $10,920 for nonimports in 1970 to $72,259 and $53,189 in 1985. With more than eight million viewers making the Grey Cup the most-watched sporting event in Canada, television revenue reached $15.6 million for 1981–83 and $33 million for 1984–86.

Then came precipitous decline and turmoil. Faced with competition from televised NFL games and a persistent perception that home-grown football was second-rate, the CFL saw TV revenues fall to $240,000 per club by 1991. Montreal lost its original franchise in 1982, then its replacement in 1987. Deficit-burdened franchises did not move but repeatedly changed hands. The purchase of the Toronto Argonauts in 1991 by millionaire Bruce McNall, actor John Candy, and hockey great Wayne Gretzky (Gretzky, Wayne) marked the most conspicuous effort to produce first-class football with highly paid U.S. stars, but the experiment failed, and McNall and Gretzky sold the club in 1994 after Candy died. Constantly fearing NFL expansion into Montreal and Toronto, CFL leaders had been discussing since the early 1970s their own expansion into the United States, which became a reality with teams in Sacramento (California) in 1993 and Las Vegas (Nevada), Shreveport (Louisiana), and Baltimore (Maryland) in 1994, but the experiment failed after just three seasons. In 1996 the CFL reverted to an eight-team all-Canadian league, then returned to its original nine for the 2002 season as the league continued to face an uncertain future.

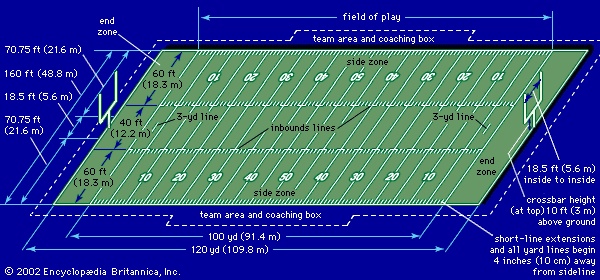

Then came precipitous decline and turmoil. Faced with competition from televised NFL games and a persistent perception that home-grown football was second-rate, the CFL saw TV revenues fall to $240,000 per club by 1991. Montreal lost its original franchise in 1982, then its replacement in 1987. Deficit-burdened franchises did not move but repeatedly changed hands. The purchase of the Toronto Argonauts in 1991 by millionaire Bruce McNall, actor John Candy, and hockey great Wayne Gretzky (Gretzky, Wayne) marked the most conspicuous effort to produce first-class football with highly paid U.S. stars, but the experiment failed, and McNall and Gretzky sold the club in 1994 after Candy died. Constantly fearing NFL expansion into Montreal and Toronto, CFL leaders had been discussing since the early 1970s their own expansion into the United States, which became a reality with teams in Sacramento (California) in 1993 and Las Vegas (Nevada), Shreveport (Louisiana), and Baltimore (Maryland) in 1994, but the experiment failed after just three seasons. In 1996 the CFL reverted to an eight-team all-Canadian league, then returned to its original nine for the 2002 season as the league continued to face an uncertain future.The play of the game