Founding Fathers

United States history

Introduction

the most prominent statesmen of America's Revolutionary generation, responsible for the successful war for colonial independence from Great Britain, the liberal ideas celebrated in the Declaration of Independence, and the republican form of government defined in the United States Constitution (Constitution of the United States of America). While there are no agreed-upon criteria for inclusion, membership in this select group customarily requires conspicuous contributions at one or both of the foundings of the United States: during the American Revolution, when independence was won, or during the Constitutional Convention, when nationhood was achieved.

the most prominent statesmen of America's Revolutionary generation, responsible for the successful war for colonial independence from Great Britain, the liberal ideas celebrated in the Declaration of Independence, and the republican form of government defined in the United States Constitution (Constitution of the United States of America). While there are no agreed-upon criteria for inclusion, membership in this select group customarily requires conspicuous contributions at one or both of the foundings of the United States: during the American Revolution, when independence was won, or during the Constitutional Convention, when nationhood was achieved. Although the list of members can expand and contract in response to political pressures and ideological prejudices of the moment, the following 10, presented alphabetically, represent the “gallery of greats” that has stood the test of time: John Adams (Adams, John), Samuel Adams (Adams, Samuel), Benjamin Franklin (Franklin, Benjamin), Alexander Hamilton (Hamilton, Alexander), Patrick Henry (Henry, Patrick), Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas), James Madison (Madison, James), John Marshall (Marshall, John), George Mason (Mason, George), and George Washington (Washington, George). There is a nearly unanimous consensus that George Washington was the Foundingest Father of them all.

Although the list of members can expand and contract in response to political pressures and ideological prejudices of the moment, the following 10, presented alphabetically, represent the “gallery of greats” that has stood the test of time: John Adams (Adams, John), Samuel Adams (Adams, Samuel), Benjamin Franklin (Franklin, Benjamin), Alexander Hamilton (Hamilton, Alexander), Patrick Henry (Henry, Patrick), Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas), James Madison (Madison, James), John Marshall (Marshall, John), George Mason (Mason, George), and George Washington (Washington, George). There is a nearly unanimous consensus that George Washington was the Foundingest Father of them all.The debate

Within the broader world of popular opinion in the United States, the Founding Fathers are often accorded near mythical status as demigods who occupy privileged locations on the slopes of some American version of Mount Olympus. Within the narrower world of the academy, however, opinion is more divided. In general, scholarship at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st has focused more on ordinary and “inarticulate” Americans in the late 18th century, the periphery of the social scene rather than the centre. And much of the scholarly work focusing on the Founders has emphasized their failures more than their successes, primarily their failure to end slavery or reach a sensible accommodation with the Native Americans.

The very term Founding Fathers has also struck some scholars as inherently sexist, verbally excluding women from a prominent role in the founding. Such influential women as Abigail Adams (Adams, Abigail), Dolley Madison (Madison, Dolley), and Mercy Otis Warren (Warren, Mercy Otis) made significant contributions that merit attention, despite the fact that the Founding Fathers label obscures their role.

As a result, the Founding Fathers label that originated in the 19th century as a quasi-religious and nearly reverential designation has become a more controversial term in the 21st. Any assessment of America's founding generation has become a conversation about the core values embodied in the political institutions of the United States, which are alternatively celebrated as the wellspring of democracy and a triumphant liberal legacy or demonized as the source of American arrogance, racism, and imperialism.

For at least two reasons, the debate over its Founders occupies a special place in America's history that has no parallel in the history of any European nation-state. First, the United States was not founded on a common ethnicity, language, or religion that could be taken for granted as the primal source of national identity. Instead, it was founded on a set of beliefs and convictions, what Thomas Jefferson described as self-evident truths, that were proclaimed in 1776 and then embedded in the Bill of Rights (Rights, Bill of) of the Constitution. To become an American citizen is not a matter of bloodlines or genealogy but rather a matter of endorsing and embracing the values established at the founding, which accords the men who invented these values a special significance. Second, the American system of jurisprudence links all landmark constitutional decisions to the language of the Constitution itself and often to the “original intent” of the framers. Once again, this legal tradition gives the American Founders an abiding relevance in current discussions of foreign and domestic policy that would be inconceivable in most European countries.

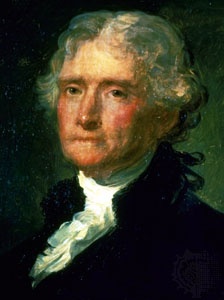

For at least two reasons, the debate over its Founders occupies a special place in America's history that has no parallel in the history of any European nation-state. First, the United States was not founded on a common ethnicity, language, or religion that could be taken for granted as the primal source of national identity. Instead, it was founded on a set of beliefs and convictions, what Thomas Jefferson described as self-evident truths, that were proclaimed in 1776 and then embedded in the Bill of Rights (Rights, Bill of) of the Constitution. To become an American citizen is not a matter of bloodlines or genealogy but rather a matter of endorsing and embracing the values established at the founding, which accords the men who invented these values a special significance. Second, the American system of jurisprudence links all landmark constitutional decisions to the language of the Constitution itself and often to the “original intent” of the framers. Once again, this legal tradition gives the American Founders an abiding relevance in current discussions of foreign and domestic policy that would be inconceivable in most European countries. Finally, in part because so much always seems to be at stake whenever the Founding Fathers enter any historical conversation, the debate over their achievement and legacy tends to assume a hyperbolic shape. It is as if an electromagnetic field surrounds the discussion, driving the debate toward mutually exclusive appraisals. In much the same way that adolescents view their parents, the Founders are depicted as heroic icons or despicable villains, demigods or devils, the creators of all that is right or all that is wrong with American society. In recent years the Founder whose reputation has been tossed most dramatically across this swoonish arc is Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas), simultaneously the author of the most lyrical rendition of the American promise to the world and the most explicit assertion of the supposed biological inferiority of African Americans.

Finally, in part because so much always seems to be at stake whenever the Founding Fathers enter any historical conversation, the debate over their achievement and legacy tends to assume a hyperbolic shape. It is as if an electromagnetic field surrounds the discussion, driving the debate toward mutually exclusive appraisals. In much the same way that adolescents view their parents, the Founders are depicted as heroic icons or despicable villains, demigods or devils, the creators of all that is right or all that is wrong with American society. In recent years the Founder whose reputation has been tossed most dramatically across this swoonish arc is Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas), simultaneously the author of the most lyrical rendition of the American promise to the world and the most explicit assertion of the supposed biological inferiority of African Americans.Since the late 1990s a surge of new books on the Founding Fathers, several of which have enjoyed surprising commercial and critical success, has begun to break free of the hyperbolic pattern and generate an adult rather than adolescent conversation in which a sense of irony and paradox replaces the old moralistic categories. This recent scholarship is heavily dependent on the massive editorial projects, ongoing since the 1960s, that have produced a level of documentation on the American Founders that is more comprehensive and detailed than the account of any political elite in recorded history.

While this enormous avalanche of historical evidence bodes well for a more nuanced and sophisticated interpretation of the founding generation, the debate is likely to retain a special edge for most Americans. As long as the United States endures as a republican government established in the late 18th century, all Americans are living the legacy of that creative moment and therefore cannot escape its grand and tragic implications. And because the American Founders were real men, not fictional legends like Romulus and Remus of Rome or King Arthur of England, they will be unable to bear the impossible burdens that Americans reflexively, perhaps inevitably, need to impose upon them.

The achievement

Given the overheated character of the debate, perhaps it is prudent to move toward less contested and more factual terrain, where it is possible to better understand what the fuss is all about. What, in the end, did the Founding Fathers manage to do? Once both the inflated and judgmental rhetorics are brushed aside, what did they achieve?

At the most general level, they created the first modern nation-state based on liberal principles. These include the democratic principle that political sovereignty in any government resides in the citizenry rather than in a divinely sanctioned monarchy; the capitalistic principle that economic productivity depends upon the release of individual energies in the marketplace rather than on state-sponsored policies; the moral principle that the individual, not the society or the state, is the sovereign unit in the political equation; and the judicial principle that all citizens are equal before the law. Moreover, this liberal formula has become the preferred political recipe for success in the modern world, vanquishing the European monarchies in the 19th century and the totalitarian regimes of Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union in the 20th century.

More specifically, the Founding Fathers managed to defy conventional wisdom in four unprecedented achievements: first, they won a war for colonial independence against the most powerful military and economic power in the world; second, they established the first large-scale republic in the modern world; third, they invented political parties that institutionalized the concept of a legitimate opposition; and fourth, they established the principle of the legal separation of church and state, though it took several decades for that principle to be implemented in all the states. Finally, all these achievements were won without recourse to the guillotine or the firing squad, which is to say without the violent purges that accompanied subsequent revolutions in France, Russia, and China. This was the overarching accomplishment that the British philosopher Alfred Lord North Whitehead (Whitehead, Alfred North) had in mind when he observed that there were only two instances in the history of Western civilization when the political elite of an emerging empire behaved as well as one could reasonably expect: the first was Rome under Augustus, and the second was the United States under the Founding Fathers.

More specifically, the Founding Fathers managed to defy conventional wisdom in four unprecedented achievements: first, they won a war for colonial independence against the most powerful military and economic power in the world; second, they established the first large-scale republic in the modern world; third, they invented political parties that institutionalized the concept of a legitimate opposition; and fourth, they established the principle of the legal separation of church and state, though it took several decades for that principle to be implemented in all the states. Finally, all these achievements were won without recourse to the guillotine or the firing squad, which is to say without the violent purges that accompanied subsequent revolutions in France, Russia, and China. This was the overarching accomplishment that the British philosopher Alfred Lord North Whitehead (Whitehead, Alfred North) had in mind when he observed that there were only two instances in the history of Western civilization when the political elite of an emerging empire behaved as well as one could reasonably expect: the first was Rome under Augustus, and the second was the United States under the Founding Fathers.The failure

slavery was incompatible with the values of the American Revolution, and all the prominent members of the Revolutionary generation acknowledged that fact. In three important areas they acted on this conviction: first, by ending the slave trade in 1808; second, by passing legislation in all the states north of the Potomac River, which put slavery on the road to ultimate extinction; and third, by prohibiting the expansion of slavery into the Northwest Territory. But in all the states south of the Potomac, where some nine-tenths of the slave population resided, they failed to act. Indeed, by insisting that slavery was a matter of state rather than federal jurisdiction, the Founding Fathers implicitly removed the slavery question from the national agenda. This decision had catastrophic consequences, for it permitted the enslaved population to grow in size eightfold (from 500,000 in 1775 to 4,000,000 in 1860), mostly by natural reproduction, and to spread throughout all the southern states east of the Mississippi River. And at least in retrospect, the Founders' failure to act decisively before the slave population swelled so dramatically rendered the slavery question insoluble by any means short of civil war.

There were at least three underlying reasons for this tragic failure. First, many of the Founders mistakenly believed that slavery would die a natural death, that decisive action was unnecessary because slavery would not be able to compete successfully with the wage labour of free individuals. They did not foresee the cotton gin and the subsequent expansion of the “Cotton Kingdom.” Second, all the early efforts to place slavery on the national agenda prompted a threat of secession by the states of the Deep South (South Carolina and Georgia were the two states that actually threatened to secede, though Virginia might very well have chosen to join them if the matter came to a head), a threat especially potent during the fragile phase of the early American republic. While most of the Founders regarded slavery as a malignant cancer on the body politic, they also believed that any effort to remove it surgically would in all likelihood kill the young nation in the cradle. Finally, all conversations about abolishing slavery were haunted by the spectre of a free African American population, most especially in those states south of the Potomac where in some locations blacks actually outnumbered whites. None of the Founding Fathers found it possible to imagine a biracial American society, an idea that in point of fact did not achieve broad acceptance in the United States until the middle of the 20th century.

Given these prevalent convictions and attitudes, slavery was that most un-American item, an inherently intractable and insoluble problem. As Jefferson so famously put it, the Founders held “the wolfe by the ears” and could neither subdue him nor afford to let him go. Virtually all the Founding Fathers went to their graves realizing that slavery, no matter how intractable, would become the largest and most permanent stain on their legacy. And when Abraham Lincoln (Lincoln, Abraham) eventually made the decision that, at terrible cost, ended slavery forever, he did so in the name of the Founders. (See also Sidebar: The Founding Fathers and Slavery.)

The other tragic failure of the Founders, almost as odious as the failure to end slavery, was the inability to implement a just policy toward the indigenous inhabitants (Native American) of the North American continent. In 1783, the year the British surrendered control of the eastern third of North America in the Peace of Paris (Paris, Peace of), there were approximately 100,000 American Indians living between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi. The first census (1790) revealed that there were also 100,000 white settlers living west of the Alleghenies, swelling in size every year (by 1800 they would number 500,000) and moving relentlessly westward. The inevitable collision between these two peoples posed the strategic and ultimately moral question: How could the legitimate rights of the Indian population be reconciled with the demographic tidal wave building to the east?

The other tragic failure of the Founders, almost as odious as the failure to end slavery, was the inability to implement a just policy toward the indigenous inhabitants (Native American) of the North American continent. In 1783, the year the British surrendered control of the eastern third of North America in the Peace of Paris (Paris, Peace of), there were approximately 100,000 American Indians living between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi. The first census (1790) revealed that there were also 100,000 white settlers living west of the Alleghenies, swelling in size every year (by 1800 they would number 500,000) and moving relentlessly westward. The inevitable collision between these two peoples posed the strategic and ultimately moral question: How could the legitimate rights of the Indian population be reconciled with the demographic tidal wave building to the east?In the end, they could not. Although the official policy of Indian removal east of the Mississippi was not formally announced and implemented until 1830, the seeds of that policy—what one historian has called “the seeds of extinction”—were planted during the founding era, most especially during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1801–09).

One genuine effort to avoid that outcome was made in 1790 during the presidency of George Washington (Washington, George). The Treaty of New York with the Creek tribes of the early southwest proposed a new model for American policy toward the Indians, declaring that they should be regarded not as a conquered people with no legal rights but rather as a collection of sovereign nations. Indian policy was therefore a branch of foreign policy, and all treaties were solemn commitments by the federal government not subject to challenge by any state or private corporation. Washington envisioned a series of American Indian enclaves or homelands east of the Mississippi whose borders would be guaranteed under federal law, protected by federal troops, and bypassed by the flood of white settlers. But, as it soon became clear, the federal government lacked the resources in money and manpower to make Washington's vision a reality. And the very act of claiming executive power to create an Indian protectorate prompted charges of monarchy, the most potent political epithet of the age. Washington, who was accustomed to getting his way, observed caustically that nothing short of “a Chinese Wall” could protect the Native American tribes from the relentless expansion of white settlements. Given the surging size of the white population, it is difficult to imagine how the story could have turned out differently.

One genuine effort to avoid that outcome was made in 1790 during the presidency of George Washington (Washington, George). The Treaty of New York with the Creek tribes of the early southwest proposed a new model for American policy toward the Indians, declaring that they should be regarded not as a conquered people with no legal rights but rather as a collection of sovereign nations. Indian policy was therefore a branch of foreign policy, and all treaties were solemn commitments by the federal government not subject to challenge by any state or private corporation. Washington envisioned a series of American Indian enclaves or homelands east of the Mississippi whose borders would be guaranteed under federal law, protected by federal troops, and bypassed by the flood of white settlers. But, as it soon became clear, the federal government lacked the resources in money and manpower to make Washington's vision a reality. And the very act of claiming executive power to create an Indian protectorate prompted charges of monarchy, the most potent political epithet of the age. Washington, who was accustomed to getting his way, observed caustically that nothing short of “a Chinese Wall” could protect the Native American tribes from the relentless expansion of white settlements. Given the surging size of the white population, it is difficult to imagine how the story could have turned out differently.The explanations

Meanwhile, the more mythical rendition of the Founders, which continues to dominate public opinion outside the groves of academe, presumes that their achievements dwarf their failures so completely that the only question worth asking is: How did they do it? More specifically, how did this backwoods province on the western rim of the Atlantic world, far removed from the epicentres of learning and culture in London and Paris, somehow produce thinkers and ideas that transformed the landscape of modern politics?

Two historical explanations have been offered, each focusing on the special conditions present in Revolutionary America favourable to the creation of leadership. The first explanation describes the founding era as a unique moment that was “postaristocratic” and “predemocratic.” In the former sense, American society was more open to talent than England or the rest of Europe, where hereditary bloodlines were essential credentials for entry into public life. The Founders comprised what Jefferson called “a natural aristocracy,” meaning a political elite based on merit rather than genealogy, thus permitting men of impoverished origins such as Alexander Hamilton (Hamilton, Alexander) and Benjamin Franklin (Franklin, Benjamin), who would have languished in obscurity in London, to reach the top tier. In the latter (i.e., predemocratic) sense, the Founders were a self-conscious elite unburdened by egalitarian assumptions. Their constituency was not “the people” but “the public,” which they regarded as the long-term interest of the citizenry that they—the Founders—had been chosen to divine. Living between the assumptions of an aristocratic and a democratic world without belonging fully to either, the Founders maximized the advantages of both.

Two historical explanations have been offered, each focusing on the special conditions present in Revolutionary America favourable to the creation of leadership. The first explanation describes the founding era as a unique moment that was “postaristocratic” and “predemocratic.” In the former sense, American society was more open to talent than England or the rest of Europe, where hereditary bloodlines were essential credentials for entry into public life. The Founders comprised what Jefferson called “a natural aristocracy,” meaning a political elite based on merit rather than genealogy, thus permitting men of impoverished origins such as Alexander Hamilton (Hamilton, Alexander) and Benjamin Franklin (Franklin, Benjamin), who would have languished in obscurity in London, to reach the top tier. In the latter (i.e., predemocratic) sense, the Founders were a self-conscious elite unburdened by egalitarian assumptions. Their constituency was not “the people” but “the public,” which they regarded as the long-term interest of the citizenry that they—the Founders—had been chosen to divine. Living between the assumptions of an aristocratic and a democratic world without belonging fully to either, the Founders maximized the advantages of both.The second explanation focuses on the crisis-driven pressures that forced latent talent to the surface. When Jefferson concluded the Declaration of Independence by proclaiming that all the signers of the document were wagering “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor” on the cause, he was engaging in more than a rhetorical flourish. For example, when Washington departed Mount Vernon for Philadelphia in May 1775, he presumed that the British would burn his estate to the ground once war was declared. An analogous gamble was required in 1787–88 to endorse the unprecedented viability of a large-scale American republic. The founding era, according to this explanation, was a propitious all-or-nothing moment in which only those blessed with uncommon conviction about the direction in which history was headed could survive the test. The severe and unforgiving political gauntlet the Founders were required to run eliminated lukewarm patriots and selected for survival only those leaders with the hard residue of unalloyed resolve.

This was probably what Ralph Waldo Emerson (Emerson, Ralph Waldo) meant when he cautioned the next generation of aspiring American leaders to avoid measuring themselves against the Founders. They had the incalculable advantage, Emerson observed, of being “present at the creation” and thus seeing God “face to face.” All who came after them could only see him secondhand.

A diverse collective

Thus far the identity, achievements, and failures of the Founding Fathers have been considered as if they were the expression of a composite personality with a singular orientation. But this is wildly misleading. The term Founding Fathers is a plural noun, which in turn means that the face of the American Revolution is a group portrait. To be sure, Washington was primus inter pares within the founding generation, generally regarded, then and thereafter, as “the indispensable figure.” But unlike subsequent revolutions in France, Russia, and China, where a single person came to embody the meaning of the revolutionary movement— Napoleon I, Vladimir Ilich Lenin (Lenin, Vladimir Ilich)/Joseph Stalin (Stalin, Joseph), Mao Zedong—the revolutionary experience in the United States had multiple faces and multiple meanings that managed to coexist without ever devolving into a unitary embodiment of authority. If one of the distinctive contributions of the American political tradition was a pluralistic conception of governance, its primal source was the pluralistic character of the founding generation itself.

All the Founders agreed that American independence from Great Britain was nonnegotiable and that whatever government was established in lieu of British rule must be republican in character. Beyond this elemental consensus, however, there was widespread disagreement, which surfaced most dramatically in the debate over ratification of the Constitution (1787–88). Two prominent Founders, Patrick Henry (Henry, Patrick) and George Mason (Mason, George), opposed ratification, claiming that the Constitution created a central government that only replicated the arbitrary power of the British monarchy and Parliament. The highly partisan politics of the 1790s further exposed the several fault lines within the founding elite. The Federalists, led by Washington, John Adams (Adams, John), and Hamilton, were opposed by the Republicans, led by Jefferson and James Madison (Madison, James). They disagreed over the proper allocation of federal and state power over domestic policy, the response to the French Revolution, the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, and the bedrock values of American foreign policy. These disagreements often assumed a hyperbolic tone because nothing less than the “true meaning” of the American Revolution seemed at stake. In what became the capstone correspondence of the Revolutionary generation, Adams and Jefferson both went to their Maker on July 4, 1826, arguing quite poignantly about their incompatible versions of the Revolutionary legacy.

All the Founders agreed that American independence from Great Britain was nonnegotiable and that whatever government was established in lieu of British rule must be republican in character. Beyond this elemental consensus, however, there was widespread disagreement, which surfaced most dramatically in the debate over ratification of the Constitution (1787–88). Two prominent Founders, Patrick Henry (Henry, Patrick) and George Mason (Mason, George), opposed ratification, claiming that the Constitution created a central government that only replicated the arbitrary power of the British monarchy and Parliament. The highly partisan politics of the 1790s further exposed the several fault lines within the founding elite. The Federalists, led by Washington, John Adams (Adams, John), and Hamilton, were opposed by the Republicans, led by Jefferson and James Madison (Madison, James). They disagreed over the proper allocation of federal and state power over domestic policy, the response to the French Revolution, the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, and the bedrock values of American foreign policy. These disagreements often assumed a hyperbolic tone because nothing less than the “true meaning” of the American Revolution seemed at stake. In what became the capstone correspondence of the Revolutionary generation, Adams and Jefferson both went to their Maker on July 4, 1826, arguing quite poignantly about their incompatible versions of the Revolutionary legacy.The ideological and even temperamental diversity within the elite leadership group gave the American founding a distinctly argumentative flavour that made all convictions, no matter how cherished, subject to abiding scrutiny that, like history itself, became an argument without end. And much like the doctrine of checks and balances in the Constitution, the enshrinement of argument created a permanent collision of juxtaposed ideas and interests that generated a dynamic and wholly modern version of political stability.

Religion and posterity

Although the Declaration of Independence mentioned “Nature's God” and the “Creator,” the Constitution made no reference to a divine being, Christian or otherwise, and the First Amendment explicitly forbade the establishment of any official church or creed. There is also a story, probably apocryphal, that Franklin's proposal to call in a chaplain to offer a prayer when a particularly controversial issue was being debated in the Constitutional Convention prompted Hamilton to observe that he saw no reason to call in foreign aid. If there is a clear legacy bequeathed by the Founders, it is the insistence that religion is a private matter in which the state should not interfere.

In recent decades Christian advocacy groups, prompted by motives that have been questioned by some, have felt a powerful urge to enlist the Founding Fathers in their respective congregations. But recovering the spiritual convictions of the Founders, in all their messy integrity, is not an easy task. Once again, diversity is the dominant pattern. Franklin and Jefferson were Deists, Washington harboured a pantheistic sense of Providential destiny, John Adams began as a Congregationalist and ended as a Unitarian, and Hamilton was a lukewarm Anglican for most of his life but embraced a more actively Christian posture after his son died in a duel. (See also Sidebar: The Founding Fathers, Deism, and Christianity.)

One quasi-religious conviction they all shared, however, was a discernible obsession with living on in the memory of posterity. One reason the modern editions of their papers are so monstrously large is that most of the Founders were compulsively fastidious about preserving every scrap of paper they wrote or received, all as part of a desire to leave a written record that would assure their secular immortality in the history books. (When John Adams and Jefferson discussed the possibility of a more conventional immortality, they tended to describe heaven as a place where they could resume their ongoing argument on earth.) Adams, irreverent to the end, declared that if it could ever be demonstrated conclusively that no future state existed, his advice to every man, woman, and child was to “take opium.” The only afterlife that the Founders considered certain was in the memory of subsequent generations, which is to say us. In that sense, this very introduction is a testimonial to their everlasting life.

- the Younger Wyatt, Sir Thomas

- the Young Pretender Charles Edward

- Theódoros Dhiliyiánnis

- Theódoros Kolokotrónis

- Theōdūrus Abū Qurrah

- T H Green

- T.H. Huxley

- thiamin

- thiazine

- thiazole

- Thibaud, Jacques

- Thibaut, Anton Friedrich Justus

- Thibaw

- Thibodaux

- thickhead

- thick-headed fly

- thickknee

- Thiebaud, Wayne

- Thierry

- Thierry, Augustin

- Thierry de Chartres

- Thiers, Adolphe

- Thietmar

- thigmotrich

- Thika