Godard, Jean-Luc

French director

born December 3, 1930, Paris, France

French film director who came to prominence with the New Wave group in France during the late 1950s and the '60s.

Godard spent his formative years on the Swiss side of Lake Geneva, where his father directed a clinic. His higher education consisted of study for a degree in ethnology at the University of Paris, interminable student café conversations, and a labouring job on a dam, which inspired his first short film, Opération Béton (1954). His ethnological interests link with the influence on his work of Jean Rouch, an anthropologist who became the first practitioner and theoretician of the documentary-like film style cinéma vérité (“cinema truth”). Filmmakers of this school employ lightweight television equipment to observe their subject with the utmost informality and so completely without preconceived bias that the theme and motifs of the film emerge only while shooting or even later, at the editing stage.

Godard's first feature film, À bout de souffle (1959; Breathless), which was produced by François Truffaut (Truffaut, François), his colleague on the journal Cahiers du cinéma, won the Jean Vigo Prize. It inaugurated a long series of features, all celebrated for the often drastic nonchalance of Godard's improvisatory filmmaking procedures. Breathless was shot without a script; Godard sketched the dialogue overnight and revised it between and during rehearsals. In subsequent films he even resorted to speaking the characters' replies to the actors from behind the camera during takes. Thus, he used improvisatory techniques sometimes to observe reality, sometimes to impose his own vision, and often to interrelate the two so as to create a strangely abstract effect. Breathless recounts the misadventures of a petty crook (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo (Belmondo, Jean-Paul), often Godard's alter ego on screen) who admires Humphrey Bogart (Bogart, Humphrey) and is betrayed to the police by an American girl. Being uncertain whether she loves him, she informs on him simply to see if she can.

For some years, Godard's work showed an increasingly desperate obsession with themes of fickleness (both male and female), indignity, caprice, and the impossibility of distinguishing a meaningful reality from the imposture perpetrated by others, by one's own mind, by ideology, and by art. Godard used the face of the actress who was then his wife, Anna Karina (Karina, Anna), as a sphinxlike icon representing this existential duplicity in several films, notably Le Petit Soldat (1960; The Little Soldier), an ironically flippant tragedy, banned for many years, about torture and countertorture. Vivre sa vie (1962; My Life to Live), a study of a young Parisian prostitute, used, with ironical solipsism, pastiches of documentary form and clinical jargon. Godard's 1963 film Le Mépris (Contempt), based on a story by the Italian novelist Alberto Moravia, marked his only venture into orthodox and comparatively expensive filmmaking. Afterward he maintained an almost unique position as an absolute, independent creator, using extraordinarily cheap alfresco production methods and enjoying repeated success on the international “art cinema” circuit. On the strength of Pierrot le fou (1965), he was asked to direct what was to be an immensely successful American film, Bonnie and Clyde (he refused it because of his distrust of the Hollywood system).

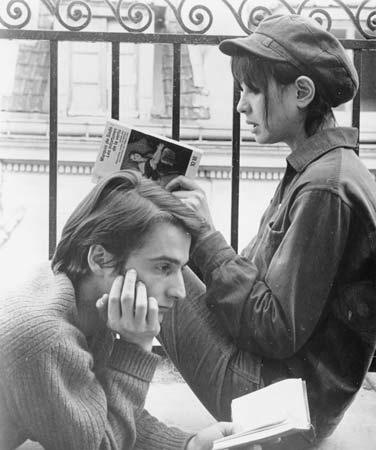

Godard offered his visual and verbal images as delusive counterfeits for a life whose meaning has become irretrievably lost or perhaps was always intrinsically absurd. These images are endowed with additional depth by his extensive culture. Increasingly, his films came to include shots of books brandished or read from and suggestive street signs or posters and dialogue that is delivered as if the performers were alienated from their roles, merely reading texts. Historically impossible or subtly fantastic settings are juxtaposed, and his films compel a disrupting awareness of the medium itself. His allusions to other films in themselves constitute an intricate maze. The heroine of The Little Soldier, for instance, is surnamed “Dreyer” after Carl Dreyer (Dreyer, Carl Theodor), a director whom Godard admires; an extract from one of Dreyer's films is watched by the heroine of My Life to Live. Alphaville (1965) features scenes from Metropolis (1926), whose director, Fritz Lang (Lang, Fritz), plays a film director in Contempt. In these ways, Godard's films become intellectual essays: in them, the acted, experienced fictions of earlier motion pictures are transformed into the illustrative ideological cinema of the late 1960s. In 1966 two features—Made in U.S.A., devoted to America, and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her), devoted to Paris—marked a nadir of Godard's generalized despair, which by then was aimed at society as well as at interpersonal relationships. An increasing interest in left-wing thought was implicit in La Chinoise (1967; its title is slang for Parisian Maoists) and was confirmed by Godard's active participation in the Paris student riots of 1968 and other demonstrations. Weekend, also made in 1967, was a hard-hitting denunciation of modern French society.

Godard offered his visual and verbal images as delusive counterfeits for a life whose meaning has become irretrievably lost or perhaps was always intrinsically absurd. These images are endowed with additional depth by his extensive culture. Increasingly, his films came to include shots of books brandished or read from and suggestive street signs or posters and dialogue that is delivered as if the performers were alienated from their roles, merely reading texts. Historically impossible or subtly fantastic settings are juxtaposed, and his films compel a disrupting awareness of the medium itself. His allusions to other films in themselves constitute an intricate maze. The heroine of The Little Soldier, for instance, is surnamed “Dreyer” after Carl Dreyer (Dreyer, Carl Theodor), a director whom Godard admires; an extract from one of Dreyer's films is watched by the heroine of My Life to Live. Alphaville (1965) features scenes from Metropolis (1926), whose director, Fritz Lang (Lang, Fritz), plays a film director in Contempt. In these ways, Godard's films become intellectual essays: in them, the acted, experienced fictions of earlier motion pictures are transformed into the illustrative ideological cinema of the late 1960s. In 1966 two features—Made in U.S.A., devoted to America, and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her), devoted to Paris—marked a nadir of Godard's generalized despair, which by then was aimed at society as well as at interpersonal relationships. An increasing interest in left-wing thought was implicit in La Chinoise (1967; its title is slang for Parisian Maoists) and was confirmed by Godard's active participation in the Paris student riots of 1968 and other demonstrations. Weekend, also made in 1967, was a hard-hitting denunciation of modern French society.By then married to the actress Anne Wiazemsky, he moved from fiction and aesthetic preoccupation to the Marxism of Herbert Marcuse (Marcuse, Herbert), Che Guevara (Guevara, Che), Frantz Fanon (Fanon, Frantz), and others. Le Gai savoir (1968; The Joy of Knowledge) is a flatly illustrated text spoken by two students named Émile Rousseau and Patricia Lumumba. His texts for the next decade exhibited a complete indifference to their appeal to the public and were intended as intellectual agitprop (i.e., agitation-propaganda): in Godard's own words, they are “not a show, a struggle.” With this ideological twist, Godard disconcerted those who had admired him, whether their particular enthusiasm was for the dexterity of his film form, for his skill in posing complex cultural riddles, or for his cool but sad recording of Western man's crises of identity. His evolution also posed a problem for his detractors, whether they criticized him for solipsism, for nihilism, or for his suspiciously complacent celebration of the ignominies of bourgeois man under the shadow of revolution. Even the minority that declared his earlier films to be honourable failures, or exercises in intellectual tedium, had to agree that, of all directors, he remained the most recklessly volatile and his development the most fascinatingly unpredictable. During the 1970s he became involved with politically militant programs for television. Numéro deux, for example, was a video experiment about family life in contemporary France and the power of ideology and the media—and was commercially unsuccessful.

Godard began making successful narrative feature films again in 1979 with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (Every Man for Himself), a story of three young Swiss people and their problems of work and love. In the 1980s he was involved in film projects at home as well as in California and Mozambique. His most notable work of the decade was his “trilogy of the sublime,” which consisted of three films—Passion (1982), Prénom: Carmen (1983; First Name: Carmen), and the highly controversial Je vous salue Marie (1985; Hail Mary)—that served as personal statements on femininity, nature, and Christianity. Godard directed few feature films in the 1990s, concentrating instead on the multipart television documentary Historie(s) de cinema, which offered his iconoclastic views on the first 100 years of motion-picture history. Éloge de l'amour (2001; In Praise of Love), a narrative film that examined the nature of love and a life in film, stirred controversy over its harsh criticism of Hollywood filmmaking.

Additional Reading

Collections of essays include Charles Barr et al., The Films of Jean-Luc Godard, 2nd rev. and enlarged ed. (1969); Toby Mussman (comp.), Jean-Luc Godard: A Critical Anthology (1968); and Colin McCabe, Godard: Images, Sounds, Politics (1980). Other material in English includes Richard Roud, Jean-Luc Godard, 2nd rev. ed. (1970); John Kreidl, Jean-Luc Godard (1980); Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki, Speaking About Godard (1998); and David Sterritt, The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible (1999).

- Ben L. Abruzzo

- Ben Lexcen

- Ben Lomond

- Benlowes, Edward

- Bennet, John

- Bennett, Arnold

- Bennett, Belle Harris

- Bennett, Floyd

- Bennett, Gwendolyn

- Bennett, James Gordon

- Bennett, Jill

- Bennett, Joan

- Bennett, Michael

- Bennett, Richard Bedford

- Bennett, Richard Rodney

- Bennett, Sir William Sterndale

- Bennett, Tony

- Bennett, Willard Harrison

- Ben Nevis

- Benn, Gottfried

- Ben Nicholson

- Bennie Moten

- Bennie Oosterbaan

- Bennigsen, Leonty Leontyevich, Graf von

- Bennigsen, Rudolf von