Greece

Introduction

officially Hellenic Republic, Greek Ellás, or Ellinikí Dhimokratía,

Greece, flag of

the southernmost of the countries of the Balkan Peninsula. It is a land of mountains and of sea. It is difficult to be far out of range of either, a fact that has had an important influence on the country's economic and historical development. Mountains have historically restricted internal communications, but the sea has opened up wider horizons. Greece has an area of 50,949 square miles (131,957 square kilometres), of which one-fifth constitutes the Greek islands. The area of Greece is approximately the same as that of England or the U.S. state of Alabama.

the southernmost of the countries of the Balkan Peninsula. It is a land of mountains and of sea. It is difficult to be far out of range of either, a fact that has had an important influence on the country's economic and historical development. Mountains have historically restricted internal communications, but the sea has opened up wider horizons. Greece has an area of 50,949 square miles (131,957 square kilometres), of which one-fifth constitutes the Greek islands. The area of Greece is approximately the same as that of England or the U.S. state of Alabama.

the southernmost of the countries of the Balkan Peninsula. It is a land of mountains and of sea. It is difficult to be far out of range of either, a fact that has had an important influence on the country's economic and historical development. Mountains have historically restricted internal communications, but the sea has opened up wider horizons. Greece has an area of 50,949 square miles (131,957 square kilometres), of which one-fifth constitutes the Greek islands. The area of Greece is approximately the same as that of England or the U.S. state of Alabama.

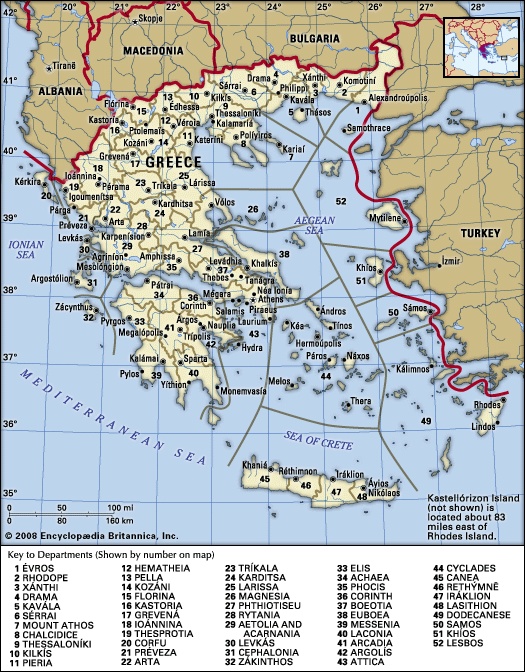

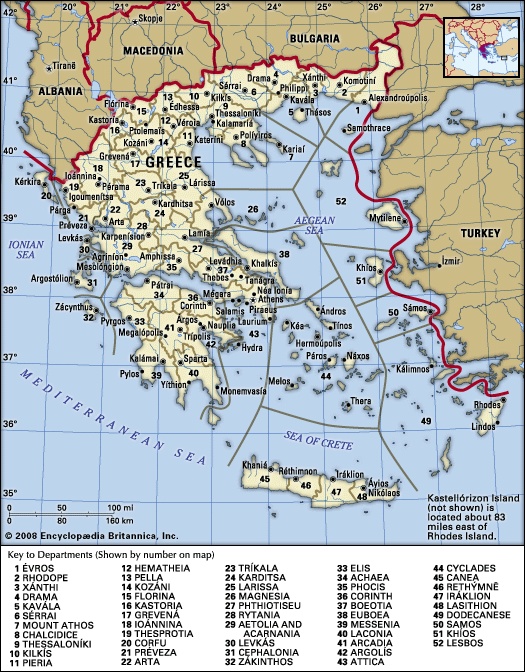

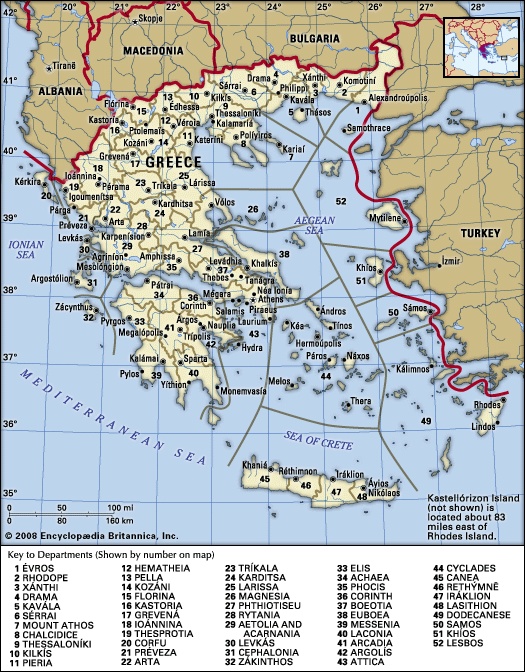

the southernmost of the countries of the Balkan Peninsula. It is a land of mountains and of sea. It is difficult to be far out of range of either, a fact that has had an important influence on the country's economic and historical development. Mountains have historically restricted internal communications, but the sea has opened up wider horizons. Greece has an area of 50,949 square miles (131,957 square kilometres), of which one-fifth constitutes the Greek islands. The area of Greece is approximately the same as that of England or the U.S. state of Alabama.The country is bordered to the west by the Ionian Sea, to the south by the Mediterranean Sea, and to the east by the Aegean Sea; only to the north and northeast does it have land borders. These run from west to east with Albania (153 miles 【247 kilometres】), Macedonia (the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia; 159 miles 【256 kilometres】), Bulgaria (295 miles 【475 kilometres】), and Turkey (126 miles 【203 kilometres】), totaling altogether 734 miles (1,181 kilometres).

Greece has more than 2,000 islands, of which 170 are inhabited; some of the easternmost Aegean islands lie just a few miles off the Turkish coast. Given this situation, it is no accident that Greece has always had a strong nautical tradition.

The country's capital is Athens, which has expanded rapidly in the period since World War II. The area around the capital (Attica) is now home to about one-third of the country's entire population.

A Greek legend has it that God distributed all of the available soil through a sieve and used the stones that remained to build Greece. The country's barren landscape has been a powerful factor impelling Greeks to migrate, a process that has continued for centuries until very recent times. The Greeks, like the Jews and Armenians, are a people of the diaspora; there are several million people of Greek descent in various parts of the world. Xeniteia, or sojourning in foreign parts, with its strong overtones of nostalgia for the faraway homeland, has been a central element in the historical experience of the Greek people.

Greece lies at the juncture of Europe, Asia, and Africa. It is heir to the heritages of classical Greece, the Byzantine Empire, and nearly four centuries of Ottoman Turkish rule. From ancient Greece the modern country inherited a sophisticated culture and a language that has been documented for almost three millennia. The language of Periclean Athens in the 5th century BC and the present-day language of the Greeks are recognizably one and the same; few languages can demonstrate such continuity. From the Byzantine Empire it has inherited Eastern Orthodox Christianity and from Ottoman rule attitudes and values that continue to be of significance, not least in shaping the country's political culture.

Greece is a country that is at once European, Balkan, and Mediterranean. It is also a country that is peculiarly burdened by its past: Greece is the only country in the world, Greek the only language, and Greeks the only people regularly prefaced by the epithet “modern.” References to Greece and Greek usually denote ancient Greece and ancient Greek. Greeks, however, take great pride in their cultural heritage, and the notion of an unbroken continuity between ancient and modern Greece is an essential element in the Greek self-image.

In 1981 Greece joined the European Community (renamed the European Union in 1994). It was the first eastern European country to do so, and its heritage of Ottoman rule and Orthodox Christianity set it apart from the existing member states. The centuries of Ottoman rule have insulated the Greek lands from many of the important historical movements, such as the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution, that shaped the destinies of the countries of western Europe. Membership in the European Union has been a factor in buttressing Greece's somewhat uncertain identity as a European country.

The land

The Greek landscape is conspicuous not only for its beauty but also for its complexity and variety. Three elements dominate. The first is the sea. A glance at the map shows that the Greek mainland is indented. Arms and inlets of the sea penetrate deeply so that only a small, wedge-shaped portion of the interior mainland is more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) from the coast. The rocky headlands and peninsulas extend out to sea as island arcs and archipelagoes; indeed, islands make up roughly 18 percent of the territory of modern Greece. The southernmost part of mainland Greece, the Peloponnese Peninsula, is joined to the mainland only by the narrow isthmus at the head of the Gulf of Corinth (Korinthiakós). The country's second landscape element is its mountainousness. Roughly 80 percent of Greece is mountain terrain, much of it deeply dissected. A series of mountain chains on the Greek mainland, aligned northwest-southeast, enclose narrow parallel valleys and numerous small basins that once held lakes. With the riverine plains (most extensive toward the coast) and thin, discontinuous strips of coastal plain, these interior valleys and basins account for the third dominant feature of the Greek landscape, the lowland. Although not extensive in Greece (accounting for 20 percent of the land area), it has played an important role in the life of the country.

The Greek landscape is conspicuous not only for its beauty but also for its complexity and variety. Three elements dominate. The first is the sea. A glance at the map shows that the Greek mainland is indented. Arms and inlets of the sea penetrate deeply so that only a small, wedge-shaped portion of the interior mainland is more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) from the coast. The rocky headlands and peninsulas extend out to sea as island arcs and archipelagoes; indeed, islands make up roughly 18 percent of the territory of modern Greece. The southernmost part of mainland Greece, the Peloponnese Peninsula, is joined to the mainland only by the narrow isthmus at the head of the Gulf of Corinth (Korinthiakós). The country's second landscape element is its mountainousness. Roughly 80 percent of Greece is mountain terrain, much of it deeply dissected. A series of mountain chains on the Greek mainland, aligned northwest-southeast, enclose narrow parallel valleys and numerous small basins that once held lakes. With the riverine plains (most extensive toward the coast) and thin, discontinuous strips of coastal plain, these interior valleys and basins account for the third dominant feature of the Greek landscape, the lowland. Although not extensive in Greece (accounting for 20 percent of the land area), it has played an important role in the life of the country.Relief

Three characteristics of geology and structure underlie these landscape elements. First, northeastern Greece is occupied by a stable block of old (Hercynian) hard rock. Second, younger and weaker rocks (predominantly of limestone origin) make up western and southern Greece. These were heavily folded in the Alp-building phase of the Tertiary Period (66.4 to 1.6 million years ago) when earth movements thrust the softer sediments east-northeast against the unyielding Hercynian block, producing a series of roughly parallel tectonic zones that gave rise to the mountain-and-valley relief sequence noted above. Third, both the Hercynian block and the Hellenidic (Alpine) ranges were subsequently raised and fractured by movements of the earth. These dislocations created the sunken basins of the Ionian and Aegean seas as well as the jagged edges so typical of Greece's landscape. Even today, earthquakes are all-too-frequent reminders that similar earth movements continue, particularly along the major fracture lines. Another consequence of the region's geologic instability is the widespread occurrence of marble (limestone altered by pressure and heat). Seismic disturbances are sometimes associated with volcanic explosions, notably involving the island of Thera (Santorin), which was virtually destroyed by a major eruption in the 2nd millennium BC. The vents of the Kaïméni Isles in the sea-filled explosion crater of Thera remain active. The island of Melos (Mílos), which rises to 2,464 feet (751 metres), is composed of young volcanic rocks. Thus, relief and geology provide the basis for describing the Greek landscape in terms of six major regions.

Central Greece: the Pindus Mountains

The central mountain range, the rugged Pindus (Píndhos) Mountains, forms the core of mainland Greece. Following the general northwest-southeast trend of the mountains of the Balkan Peninsula, the Pindus sweep down from the Albanian and Macedonian frontiers, creating a powerful communications barrier. Two passes (Métsovon and Mount Timfristós) divide the range into three units: a fairly open one in the north where impervious shales and sandstones have weathered into extensive upland valleys and gently inclining hills; the Pindus proper, some 20 miles in width and predominantly limestone, in the centre; and an almost uncrossable southern zone, some 50 miles wide, deeply dissected by winding rivers and composed of a mixture of limestone, slates, and sandstones. The highest point, Mount Smólikas, 8,652 feet (2,637 metres) high, is found in the northern Pindus.

Northeastern Greece: Macedonia and Thrace

A number of topographic regions surround the main mountainous core and are often penetrated by extensions of it. The northernmost part, roughly the regions of Greek Macedonia (Makedhonía) and Thrace (Thráki), extends in a long, narrow, east-west band between the Aegean coast and the frontier with the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria. It consists of a series of forest-clad, crystalline mountain massifs and plateaus created by the fracturing of the old Hercynian block and separated from each other by the alluvial deposits of the five great rivers of northern Greece, the Maritsa, Néstos, Struma, Vardar, and Aliákmon rivers. The complexities of that fracturing account for the odd three-pronged shape of the Chalcidice (Khalkidhikí) Peninsula, on whose easternmost prong, Áyion (Holy) Mountain, is located Mount Athos (Athos, Mount) (Áthos), the famous site of Greek Orthodox monastic communities. Along and beyond the Bulgarian border rise the Rhodope (Rhodope Mountains) (Rodhópis) Mountains, composed mainly of sharp-edged and frequently sloping plateaus, often rising more than 7,000 feet (1,800 metres) and reaching 7,287 feet (2,212 metres) at Mount Órvilos. The Maritsa (Maritsa River) (Évros) River in its low-lying, marshy valley marks the Turkish border. From here to the lower Struma (Strimón) River extends a succession of plains, often swampy (like the deltaic plain of the lower Néstos), some of which have been turned into fertile agricultural land (like the former Lake Akhinós). Inland there are basins of structural origin (such as the Dhrámas Plain). The lakes of Korónia and Vólvi, which separate the Chalcidice Peninsula from the rest of the coastal region, also occupy structural depressions. Farther west the large plain drained by the Vardar (Axiós) and lower Aliákmon rivers is being continually extended as the river deltas push out into the Gulf of Thérmai (Thermaïkós). The forested Vérmion (Vírmion) Mountains and, beyond them, the barren inland basins around Lakes Vegorrítis and Kastorías mark the boundary with the Pindus Mountains.

Eastern Greece: Thessaly and Attikí

This region epitomizes the physical geography of Greece. To the west are the massive limestones so characteristic of northern and western Greece, while to the east the peninsula of Attikí (Attica) represents the western margin of the old (Hercynian) crystalline rocks of the Aegean shores. Essentially an upland area, its relief is articulated by four northwest-southeast-trending spurs thrusting out from the main Pindus mass. A number of distinctive basins and plains lie amid these upland ribs. The northernmost, a rather broken spur called the Kamvoúnia Mountains, runs along the coast of the Gulf of Thérmai and continues south to form the peninsula bounding one side of the Vólou Bay. Among its peaks are Mount Olympus (Olympus, Mount) (Ólimbos)—the mythical seat of the gods, whose often cloud-topped summit rises to 9,570 feet (2,917 metres), the highest point in Greece—and the equally fine peaks of Mount Óssa and Mount Pelion (Pílion). The next spur on the west is the Óthris mountain range, which continues across the narrow Oreón (Oreón) Channel in the northern sector of the long, narrow island of Euboea (Évvoia). Between the two spurs lie the ancient basins (formerly the site of lakes) of Thessaly (Thessalía), Tríkala (Tríkkala), and Lárisa, drained by the Piniós. Just to their south the basin of Almirós, of similar origin, lies around Vólou Bay.

To the southwest, the third spur leaving the Pindus is that of the Oíti, continued in the Ókhi Mountains of southern Euboea. Just before the Oíti reaches the sea, near the head of the Gulf of Maliakós, is the pass of Thermopylae (Thermopílai), scene of the famous battle of antiquity. The last (and perhaps the most important) of the four spurs thrusting down into eastern Greece is the one that curves away to the southeast through the twin-peaked mass of Mount Parnassus (Parnassus, Mount) (Parnassós). This mountain rises to 8,061 feet (2,457 metres) and was held to be the home of the Muses. The view from its summit at sunrise, with a broad expanse of the heart of Greece gradually unfolding, is regarded as one of the finest in the world. The range continues as the backbone of the peninsula lying between the Gulf of Euboea and the Gulf of Corinth, and it reaches as far as Mount Párnis, just to the north of Athens. To its north lie the plains of Phocis (Fokís) and Boeotia (Voiotía), and around its southern tip lie the depressions of Attikí, hotter and more arid but with a strategic importance that helps to explain the rise of Athens.

Southern Greece: the Peloponnese

The entire southern portion of mainland Greece forms a peninsula lying to the south of the Gulf of Corinth. Technically, this region, the Peloponnese, or Pelopónnisos, also known as the Morea, is now an island, for the 3.9-mile Corinth Canal cuts across the narrow neck of land formerly separating the Gulf of Corinth from that of Aegina (Aíyina). The Peloponnese consists of an oval-shaped mountain mass with peaks rising to 7,800 feet and four peninsular prongs that point southward toward the island of Crete. At its heart are the arid limestone plateaus of Arcadia (Arkadhía), where streams disappear underground into the soluble rock and from which the barren upland of the Taïyetos Mountains (Taíyetos Mountains) (7,800 feet) extends southward to form the backbone of one of the southern peninsulas. A thin fringe of fertile coastal plain in the north and west, together with the larger alluvial depressions forming the Gulfs of Laconia (Lakonikós), Messenia (Messiniakós), and Árgolis, surrounds this mountainous core. The coast is indented and offers some fine harbours.

The entire southern portion of mainland Greece forms a peninsula lying to the south of the Gulf of Corinth. Technically, this region, the Peloponnese, or Pelopónnisos, also known as the Morea, is now an island, for the 3.9-mile Corinth Canal cuts across the narrow neck of land formerly separating the Gulf of Corinth from that of Aegina (Aíyina). The Peloponnese consists of an oval-shaped mountain mass with peaks rising to 7,800 feet and four peninsular prongs that point southward toward the island of Crete. At its heart are the arid limestone plateaus of Arcadia (Arkadhía), where streams disappear underground into the soluble rock and from which the barren upland of the Taïyetos Mountains (Taíyetos Mountains) (7,800 feet) extends southward to form the backbone of one of the southern peninsulas. A thin fringe of fertile coastal plain in the north and west, together with the larger alluvial depressions forming the Gulfs of Laconia (Lakonikós), Messenia (Messiniakós), and Árgolis, surrounds this mountainous core. The coast is indented and offers some fine harbours.Western Greece: Epirus and Arkananía

The distinctiveness of the western side of the Greek mainland (consisting of Epirus 【Ípiros】 and Arkananía) north of the Gulf of Corinth to the Albanian frontier and the offshore Ionian (Iónioi) Islands is enhanced by the fact that the barrier effect of the Pindus and the ameliorating climatic influences from the west that result in a quite different landscape from that of the rest of Greece have exaggerated the historic isolation from the other areas of mainland Greece. Fertile basins are not well developed, constricted as they are by the parallel ranges of the coastal mountains. The mountain regions themselves, however, are adequately supplied with rainfall. The flat, alluvial plain of Árta, built up from detritus brought down by the Arachthos (Árakhthos) River, has become, with irrigation, a fertile agricultural region.

The islands of Greece

The Ionian Islands off the western coast of Greece structurally resemble the folded mountains of Epirus. Of the seven main islands, Corfu (Kérkira), opposite the Albanian frontier, is the northernmost. It is fertile and amply endowed with well-watered lowland. The other islands, Paxos (Paxoí), Leukas (Levkás (Leucas)), Skorpiós, Ithaca (Itháki), Cephalonia (Cephallenia) (Kefallinía), and Zacynthus (Zákinthos), lie farther south. Lack of rainfall accentuates their gaunt, broken limestone relief, although Leukas and Zacynthus have sheltered eastern plains. The Aegean Islands, also exhibiting the characteristic landforms of the mainland, are situated in distinct clusters in the Aegean Sea, east of the Greek mainland.

In the north, off Thrace, lie Thásos (Thasos) (an oval block of ancient mineral rocks similar in composition to neighbouring blocks on the mainland) and harbourless Samothrace (Samothráki), an island of volcanic origin. Lemnos (Límnos), situated midway between Asia Minor and Áyion Mountain peninsula, is almost cut in two by the northern Pourniás Bay and the deep southern harbour afforded by the Bay of Moúdhrou.

To the southeast the rocky but sheltered islands of Lesbos (Lésvos), Chios (Khíos), and Sámos (Samos) lie close to the Turkish coast and are extensions of peninsulas on the coast of Asia Minor. Across the central Aegean, near northern Euboea, lie the Northern Sporades (Vórioi Sporádhes), or “Scattered Islands”; their crystalline rocks are similar to those of the Greek mainland. Farther south, in the heart of the Aegean, lie the Cyclades (Kikládhes), “Islands in a Circle.” These roughly centre on Delos (Dhílos) and represent the tips of drowned mountain ridges continuing the structural trends of Euboea and the region around Athens.

Between the Cyclades and the Turkish coast, the Dodecanese (Dhodhekánisos) group, with Rhodes (Ródhos) the largest of a dozen major islands, has a varied geologic structure ranging from the gray limestones of Kálimnos, Sími, and Khálki to the complete ancient volcanic cone that forms Nísiros.

Finally, the long narrow shape of Crete (Kríti) stands to the south at the entrance of the Aegean. By far the largest of the Aegean Islands and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean (3,190 square miles), Crete is geologically linked to the south and west of mainland Greece. Its rugged, deeply ravined, asymmetrical limestone massif, falling steeply to the south, is so divided as to resemble four separate islands when seen from a distance: the westernmost Lévka (Lévka Mountains) (“White”) Mountains; the central Ídhi (or Psilorítis) Mountains, with Crete's highest point, the summit of Mount Ídhi, Stavros, 8,058 feet (2,456 metres) high; the east-central Dhíkti Mountains; and the far eastern Thriptís (Thriftí) Mountains. Another range, the Asterousia (or Kófinos) Mountains, runs along the south-central coast between the Mesará Plain and the Libyan Sea. Of Crete's 650 miles (1,046 kilometres) of rocky coastline, it is the more gradual slope on the northern side of the island that provides several natural harbours and coastal plains.

Climate

The basically Mediterranean climate of Greece is subject to a number of regional and local variations occasioned by the country's physical diversity. In winter the belt of low-pressure disturbances moving in from the North Atlantic shifts southward, bringing with it warm, moist, westerly winds. Squalls and spells of rain ruffle the Aegean, but sunshine often breaks through the clouds. As the low-pressure areas enter the Aegean region, they may draw in cold air from those eastern regions of the Balkans that, sheltered by the Dinaric mountain system from western influences, are open to climatic extremes emanating from the heart of Eurasia. This icy wind is known as the boreas. Partly as a result, Thessaloníki (Salonika) has an average January temperature of 43° F (6° C), while Athens has 50° F (10° C) and Iráklion (Hérakleion) 54° F (12° C). Shilok, or warm winds, are similarly drawn in from the south. The western influences bring plentiful rain to the Ionian coast and the mountains behind it; winter rain also starts early, and snow lingers into spring. At Corfu, January temperatures average 50° F (10° C), and the island's average annual rainfall is 52 inches (1,320 millimetres), compared with the total on Crete of 25 inches and the total at Athens of 16 inches. On Crete, snow is almost permanent on the highest peaks.

In summer, when the low-pressure belt swings away again, the climate is hot and dry almost everywhere, with the average July sea-level temperature approaching 80° F (27° C), although heat waves can push the temperature up over the 100° F (38° C) mark for a day or so. Topography is again a modifying factor: the interior northern mountains continue to experience some rainfall, while all along the winding coast the afternoon heat is eased slightly by sea breezes. In other regions, such as Crete, the hot, dry summers are accentuated by the parching neltemi, or Etesian winds (etesian wind), which become drier and drier as they are drawn southward.

In all seasons—perhaps especially in summer—the quality of light is one of Greece's most appealing attractions. However, atmospheric pollution has become a serious problem in the cities, notably Athens, and a hazard to the ancient monuments.

Drainage

The main rivers of Greece share several characteristics: in their upper courses most flow in broad, gently sloping valleys; in their middle courses they plunge from intermontane basin to basin through narrow, often spectacular gorges; in their lower courses they meander across the coastal plain to reach the sea in marshy, ever-growing deltas. Most rivers are very short. In limestone districts a generally permeable surface with sinkholes (katavóthra) leading to underground channels complicates the drainage network. In all regions river regimes are erratic, unsuitable for navigation, and of limited usefulness for irrigation. The Vardar, Struma, and Néstos, which cross Greek Macedonia and Thrace to enter the northern Aegean, are the major rivers, but only because they drain large regions beyond the Greek frontier. Also in the northeast are the eastward-flowing Aliákmon and Piniós (Peneus). In the Peloponnese, only the Evrótas is noteworthy.

Plant and animal life

As in other Balkan countries, the vegetation of Greece is open to influences from several major biogeographic zones, with the major Mediterranean and western Asian elements supplemented by plants and animals from the central European interior. Add to this the climatic effects of altitude, the contrast between north and south, and the role of local relief, together with the ubiquitous human factor, the result of some eight or nine millennia of settlement and land use, and it is not difficult to appreciate either the subtlety or the complexity of the vegetation mosaic. Degraded plant associations (reduced in variety and height of species and density of plant cover) and soil erosion are commonplace.

On the mountain flanks, and in the north generally, the central European types of vegetation prevail. In central and southern regions and in narrow belts along the valleys of the mountains, about half the land is under scrub of various kinds; and maquis, the classic Mediterranean scrub complex—with oleander, bay, evergreen oak, olive, and juniper—is particularly well developed in the Peloponnese. Evergreen trees and shrubs and herbaceous plants are found in the lowlands, with the flowers offering brilliant patterns in springtime. Pines, planes, and poplars line the rivers, the higher slopes, and the coastal plains. Oak, chestnut, and other deciduous trees are found in the north, giving way at higher altitudes to coniferous forests dominated by the Grecian fir, in which clearings are carpeted in spring and summer with irises, crocuses, and tulips. Forests and scrub are found at the highest levels; the black-pine forests covering Mount Olympus are especially noteworthy.

The forested zones, especially in the north, harbour such European animals as the wildcat, martin, brown bear, roe deer, and, more rarely, wolf, wild boar, and lynx. Animals of the Mediterranean regions include jackals, wild goats, and porcupines, all adapted to the lack of moisture and to the heat. Birds include pelicans, storks, and herons, while many varieties from farther north winter in Greece. Reptile and fish life is rich and varied.

Settlement patterns

In terms of human geography, Greece can be described as “classical Mediterranean” only in part, the other part being distinctly “Balkan.” History rather than the physical environment accounts for fundamental paradoxes and contrasts in settlement pattern, social composition, and demographic trends that cannot be explained simply by reference to the difference between “Old Greece” and territories annexed in the early 20th century. For instance, although Greece is an “old country,” relatively densely occupied in prehistoric times and well settled and much exploited in, and since, ancient times (as the large number of ancient monuments and important archaeological sites testifies), instability is as characteristic of Greece's settlement pattern as of its history. New villages, associated not only with Ottoman colonization but more recently (the first third of the 20th century) with agrarian reform, are juxtaposed with some of the most ancient towns of Mediterranean Europe (including Mycenea, Pílos, Thíra, Árgos, Athens, Sparta, and Thebes). Traditionally, towns as well as villages have depended on the food potential of the surrounding land. This self-sufficiency, the autarkeia of the ancient city-states, survives in the remote villages, perforce traditional in their isolation, of mountainous Greece. Only Corinth and, above all, Athens were major trading centres in ancient times. The other major nuclei of trade were found where routeways (sea and land) coincided with cultivatable land. From the Byzantine period onward, fortification became an essential factor for monastic and secular settlement alike, emphasizing the importance of the mountain regions and of sites “perched” above lowland. As late as the 1960s, more than 40 percent of Greece's population lived in mountain regions. Intermittent periods of relative stability saw a return to the plains where the settlement pattern, dispersed or nucleated, often geometrically laid out, thus always seems to be “new.”

Greeks have preserved a strong sense of community. Village life remains a powerful influence, and village-square discussions reflect the cosmopolitan nature of the communities. This holds true despite the decline of the rural population in the late 20th century (still, more than one-third of Greece's total population is classified as rural). The same may be said about the small villages and towns at the bottom of the urban hierarchy. At the other end of the urban scale, however, Greece's larger towns and cities have gained considerably in size and commercial importance since the 1970s. Athens, with a population of 750,000 increasing to about 3,000,000 for the entire metropolitan area (including the port of Piraeus), stands alone, but towns such as Thessaloníki, Patras, Vólos, Lárisa (Lárissa), and, on Crete, Iráklion are all fast-growing centres. Almost two-thirds of the population is now classified as urban, and another 10 percent as semiurban. Urbanization also is reaching out into the countryside, especially where excessive fragmentation of landholding (a consequence of agrarian reform) attracts urban-based financial and marketing entrepreneurs. Curiously, early Greek city planning, unlike Roman, has bequeathed little to the layout of modern urban centres.

The people

Linguistic, ethnic, and religious background

The inherent instability of the Balkan Peninsula—located as it is at the crossroads of invading Turks, migrating Slavs, and colonizing powers from western or central Europe (Venetians, Austro-Hungarians)—has bequeathed a bewildering amount of cultural confusion to Greece. Even in the south or on the islands, centuries of population migration and forced population exchanges continued well into the 20th century. Despite the long Ottoman administration (perhaps because of its failure to create a nation-state), all but a very small part of the population belong to the Church of Greece (Greece, Church of) (Greek Orthodox church). This body appoints its own ecclesiastical hierarchy and is headed by a synod of 12 metropolitans under the presidency of the archbishop of Athens. The Greek church has links in dogma with the other Orthodox churches. Virtually all Cretans belong to a special branch of the Church of Greece, headed by the archbishop of Crete and directly responsible to the patriarchate of Constantinople.

The Muslim minority, which constitutes most of the non-Orthodox group, is mainly Turkish and is concentrated in western Thrace and the Dodecanese. Roman and Greek Catholics, concentrated in Athens and the western islands formerly under Italian sway, account for the rest, except for a few thousand adherents of Protestant churches and of Judaism, the last group having been much reduced in numbers by the Nazi genocide of World War II.

In terms of ethnic composition, Greeks again make up all but a small part of the total, the remainder being composed of Macedonians, Turks, Albanians, Bulgarians, Armenians, and Gypsies. Except in Cyprus, southern Albania, and Turkey, there are no major enclaves of Greeks in nearby countries, although Greek expatriate communities play a distinctive role in western Europe, North and South America, and Australia.

Demography

The Greek population has never displayed high rates of growth, although—despite losses in a succession of wars and constant emigration as a result of poor economic conditions—it has usually shown a regular increase since the first census, in 1828. Most of its growth in the years since Greece gained its independence from the Turks in 1832 resulted from two factors—annexations of surrounding areas (the Ionian Islands; Thessaly and Árta; Epirus, Greek Macedonia, and Crete; Thrace; and the Dodecanese) and the influx of some 1,300,000 Greek refugees from Asia Minor in the 1920s. Emigration has continued to be a limiting factor: the years 1911–15 were an active period, and emigration became particularly heavy after World War II. The most common destinations of the emigrants have been the United States, Canada, Australia, and, somewhat later, Germany, Belgium, and Italy.

With a total population, according to the 1991 census, of 10,264,156, the two decades since the demographically stagnant 1950s and '60s have seen a remarkable revitalization in Greece. This is, however, almost wholly due to international population movements, not to an increase in natural growth rates, which remain low. Within the country, the contrast between regions losing population (two-thirds of the southern Peloponnese, all the Ionian isles except Corfu, the mountains of central, southwestern, and northeastern mainland Greece, and most of the islands of the eastern Aegean) and those rapidly gaining people (Attikí and other districts outside the major cities) holds a range of important social and political implications at all levels.

The economy

Despite a rapid rate of growth in the post-World War II period, Greece's economy is one of the least developed in the European Union (EU). Natural resources are limited, industrialization has been achieved only partially, and there are chronic problems with the balance of payments. Shipping, tourism, and, decreasingly, migrant remittances are the mainstays of the economy. By the 1990s receipts from tourism amounted to one-quarter of the trade deficit.

Despite a rapid rate of growth in the post-World War II period, Greece's economy is one of the least developed in the European Union (EU). Natural resources are limited, industrialization has been achieved only partially, and there are chronic problems with the balance of payments. Shipping, tourism, and, decreasingly, migrant remittances are the mainstays of the economy. By the 1990s receipts from tourism amounted to one-quarter of the trade deficit.Although the Greek economy has been traditionally based on free enterprise, many sectors of the economy have come under direct or, through the banks, indirect government control. This process of expanding state ownership of the economy has, historically, been associated as much with right-wing as with centre to left governments. Trade unions, which are fragmented and highly politicized, wield significant power only in the public sector. Measures were taken in the late 1980s and the early 1990s to diminish the degree of state control of economic activity. Following entry into the European Union, Greece has been a major beneficiary of subsidies for its generally inefficient agricultural sector and for infrastructural projects. Rates of productivity, however, remain low in both the agricultural and industrial sectors, and the development of the country's economy has lagged behind that of its EU partners. Unemployment, hitherto low, has grown as temporary migrants to other European countries have returned to Greece because of those countries' declining demand for immigrant labour. However, some sectors of the economy, notably shipping, have shown considerable dynamism.

Resources

Greece has few natural resources. Only in the case of nonferrous metals are there substantial deposits. Of these the most important is bauxite, reserves of which amount to more than 650 million metric tons.

Fossil fuels, with the exception of lignite of low calorific value, are in short supply. There are no deposits of bituminous coal, and oil production, based on the Prinos field near the island of Thasos, is very limited. The complex dispute between Greece and Turkey that developed in the 1970s over the delineation of the two countries' respective continental shelves—and hence the right to such minerals, in particular oil, as may exist under the Aegean seabed—shows no sign of being resolved.

Much of Greece's electrical power needs are supplied by lignite-fueled power stations and by hydroelectric power. Recently, attention has been given to the possibilities of solar and wind power.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Greece's agricultural potential is hampered by poor soil, low rainfall, a system of landholding that has resulted in the proliferation of uneconomic smallholdings, and a general flight from the countryside to either the towns or overseas. About 30 percent of the land area is cultivable, the remainder consisting of scrub or forest. Only in the plains of Thessaly, Macedonia, and Thrace is cultivation possible on a reasonably large scale. Here corn (maize), wheat, barley, sugar beets, cotton, and tobacco are grown, Greece being a major EU producer of the last two items.

Other crops grown in considerable quantities are olives (much of the annual crop being turned into olive oil), grapes, melons, peaches, tomatoes, and oranges, which are exported to other EU countries. Historically, Greek wine production, including the resin-flavoured retsina, has been primarily for domestic consumption, but efforts have been initiated to produce wines of higher quality for the world market.

Although inefficient, Greek agriculture has benefited substantially from EU subsidies, and there are many signs of growing rural prosperity. The importance of the agricultural sector to the economy, however, is diminishing.

Forests, mostly state-owned, cover approximately one-fifth of the land area, but they are subject to major forest fires. Forest products make no significant contribution to the economy.

Greece's huge coastline and numerous islands have given rise to a fishing industry. However, overfishing and failure to conserve fish stocks properly have lessened the contribution of fishing to the economy.

Industry

The industrial sector in Greece is weak. An established tradition exists only in the production of textiles, processed foods, and cement. (What is said to be the world's largest cement factory is located in Vólos.) In the past, private investment has been oriented much more toward real estate than toward industry, and concrete apartment blocks proliferate throughout the country. In the 1960s and '70s, taking advantage of an investment regime that privileged foreign capital, Greek shipowners invested significantly in sectors such as oil refining and shipbuilding. Shipping continues to be a key industrial sector, with the merchant fleet being one of the largest in the world, even if many of its ships are older than the world average. In the 1970s many ships that had hitherto registered under flags of convenience returned to the Greek flag. The fact that Greek ships, predominantly bulk carriers, are principally engaged in carrying cargoes between third countries renders the shipping industry vulnerable to downturns in international economic activity.

Since the 1960s tourism has developed markedly, although Greece has not had much success in attracting high-spending tourists and is facing growing competition from Turkey. The number of tourists tripled between the early 1970s and the late 1980s. Most tourists come from other European countries. The emergence of a consumer society has created a seemingly insatiable demand for imported consumer goods, with negative consequences for the balance of trade. Road transport has improved immeasurably over the past 50 years, and there is a well-developed network of truck- and car-carrying ferries linking mainland Greece to the numerous islands and to Italy.

Finance

The central bank is the Bank of Greece. A significant number of the country's commercial banks are state-controlled. In the early 1990s banks controlled by the state held some 70 percent of total deposits. There is also a considerable degree of state control of the insurance sector.

In the early 1990s 118 public companies were quoted on the Athens stock exchange. For many Greeks, however, real estate, foreign currency, gold, and jewelry have proved a more attractive investment than stocks and shares. A pension and social insurance system of byzantine complexity is a major obstacle to economic modernization. The main social security fund, the Social Insurance Institute (IKA), is prone to recurrent crises in funding.

Trade

By the early 1990s some two-thirds of Greece's trade was with the other member countries of the European Union, the two main trading partners being Germany and Italy. Basic manufactures (e.g., steel, aluminum, cement, and textiles), miscellaneous manufactured items (e.g., clothing), and food (including livestock) each accounted for under one-quarter of exports; refined petroleum and petroleum-based products constituted a further 10 percent. Exports grew rapidly in the 1970s but slowed markedly in the '80s. Shipping and tourism contributed just over 10 percent to the gross domestic product (GDP) in the early 1990s, but there was a serious deficit in the balance of payments. This was offset by borrowing, limited foreign investment, and, to a decreasing extent, by emigrant remittances.

Transportation

Internal communications in Greece have, historically, been poor. Only during the post-World War II period have all the country's villages become accessible to wheeled traffic (and linked to the national electricity grid). There are no navigable rivers and only one canal, the Corinth Canal (completed in 1893), which divides the Peloponnese from mainland Greece. Although the canal significantly shortens the sea route from the Italian ports to Piraeus, the port of Athens, it has never fulfilled the economic expectations of its builders, because of its shallow draft and narrow width.

Railway construction got under way in the 1880s, and, given the rugged terrain of the country, it involved some difficult feats of engineering. The total track is slightly under 1,600 miles in length, including the narrow-gauge railway network in the Peloponnese. The railway system is being modernized with the aid of EU funding. Trunk roads are inadequate by European standards, and Greece has one of the worst automobile accident records in Europe.

Public transport in the Athens metropolitan area is heavily dependent on an overcrowded and unreliable bus network. After many postponements, work on the much-needed Athens metro commenced in earnest in 1993. This will supplement the small suburban railroad network linking Athens' northern suburb of Kifisiá with the port of Piraeus.

The extensive internal bus-and-ferry network has been augmented since the 1960s by the development of a domestic flight network linking Athens with 25 domestic airports. The country's main airports are Ellinikón in suburban Athens (to be replaced in the late 1990s by an entirely new airport at Spáta in Attikí) and Macedonia, near Thessaloníki. Other international airports, which service the country's important tourist industry, are to be found on the islands of Crete (Iráklion), Corfu, Rhodes, Cos, and Lesbos and at Alexandroúpolis in Thrace and Andravída in the northwestern Peloponnese. The national carrier is Olympic Airways (Olympic Airlines), which is 51-percent state-owned.

Administration and social conditions

Government

Constitutional framework

The current constitution was introduced in 1975 following the collapse of the 1967–74 military dictatorship. The considerable powers it vouchsafed to the president were never invoked before they were reduced in the constitutional revision of 1986. Presidential powers are now largely ceremonial. The president is elected by the parliament (Vouli) and may hold office for two five-year terms.

The prime minister, who has extensive powers, must be able to command the confidence of the parliament. The latter consists of 300 deputies and is elected for a four-year term by direct, universal, and secret ballot. It has the power to revise the constitution, as happened in 1986. A distinctive feature of the electoral system is the practice of incumbent governments, of whatever political hue, amending the electoral law to suit their own political advantage. Voting is compulsory.

The party system

Although the political system is in the process of modernization, many elements of traditional politics remain, notably the personalistic nature of the party system, with parties being heavily dependent on the charisma of their (frequently elderly) leaders and the importance of patronage at all levels.

There are three main political concentrations: the right, the centre, and the left. In the 1990s these were represented respectively by New Democracy (ND (New Democracy)), the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), and the Communist Party of Greece (KKE). New Democracy, founded by the veteran conservative politician Constantine Karamanlis, has progressively espoused “neoliberal,” antistatist policies meant to limit the power of the state and to encourage private initiatives. PASOK, although it has substantially moderated the Third World liberationist rhetoric of its earlier years, retains a strong commitment to a radical foreign policy and an idiosyncratic form of socialism, which reflects the fact that only some 40 percent of the working population are wage or salary earners (the remaining 60 percent being self-employed). On the far left the KKE advocates a Soviet-style communism even after the demise of the Soviet Union. The broadly “Eurocommunist” Coalition of the Left and Progress has limited electoral appeal.

Local government

The country is divided into 13 geographic regions (9 mainland and 4 insular). These, in turn, are further subdivided into 51 departments (nomoi), each administered by a government-appointed prefect (nomarkhis). There is a government minister with special responsibility for Macedonia and Thrace.

The governmental system is highly centralized. The powers of local government are severely circumscribed by its inability to raise revenue.

Armed forces

The military has been a major arbiter of political life during the 20th century, but there has been no sign of political activity since 1974. Greece's expenditure on defense, at some 6 percent of GDP, is the highest in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. Conscription for men is universal, the period of compulsory active service lasting 19 to 23 months. Women have the right to volunteer for service.

Judicial system

The judicial system is essentially the Roman law system prevalent in continental Europe. The two highest courts are the Supreme Court (Areios Pagos), which deals with civil and criminal cases, and the Council of State (Symvoulion Epikrateias), which is responsible for disputes arising out of administration. A Court of State Auditors has jurisdiction in a number of financial matters. A Special Supreme Tribunal, whose members include the heads of the three courts mentioned above, deals with disputes arising out of the interpretation of the constitution and checks the validity of parliamentary elections and referenda.

Education

Education has long been prized in Greece both as an end in itself and as a means of upward social mobility. Wealthy Greeks of the diaspora have been major benefactors of schools and universities in their homeland. The educational system is somewhat rigid and heavily centralized, but the rate of literacy is high. Because of the inadequacies of state education, many children attend private phrontistiria, or institutions providing supplementary coaching outside normal school hours.

Competition for university places, which hold out the prospect of job security, is exceptionally severe. The oldest university-level institutions are the National Capodistrian University of Athens (1837), the National Technical University of Athens (1836), and the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki (1925). This last institution has a tradition of innovation as compared with the more conservative University of Athens. From the 1960s to the '80s, a number of new universities were founded in Ioánnina, Patras, Thrace, Crete, Corfu, and the Aegean. However, they are often inadequately equipped and still do not offer a sufficient number of places to satisfy the demand for university-level education, forcing many Greek students to study abroad. Although there is a constitutional ban on private universities, a number of university-type institutions, some of dubious quality, have come into existence.

Health and welfare

Major strides have been made in the post-World War II period in eradicating diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, typhoid, and dysentery. There are more doctors per person in Greece than in most of the other member countries of the European Union, and in the 1980s the PASOK government of Andreas Papandreou instituted a national health system. Many Greeks, however, where they can afford it, choose to travel abroad for medical care. Pension provision in Greece is a subject of extraordinary complexity. Some 80 percent of the working population are insured under the Social Insurance Institute and the Agricultural Insurance Organization (OGA; for farmers) programs.

During the 1980s important changes were introduced in Greek family law. Civil marriage was instituted in parallel with religious marriage, the dowry system was abolished (in theory), divorce was made easier, and the hitherto dominant position of the father in the family was restricted.

Cultural life

The important sites of Greek antiquity that attracted European noblemen to the Greek lands in the 18th century, and which were such a potent influence on architectural styles in the West, continue to attract tourists from all over the world. Newly excavated sites such as the supposed tomb of Philip II of Macedon at Verghina and the Pompei-like remains at Thera are further indications of an astonishingly rich heritage from antiquity that has still not been fully explored. Over the past century there has been a greater awareness of the richness of the architectural and artistic heritage of the medieval empire of Byzantium.

The arts

Against the background of this extraordinary artistic heritage, Greece enjoys a thriving cultural life. It is in the field of literature that Greece has made its greatest contributions. Constantine Cavafy (Cavafy, Constantine) (1863–1933), who lived most of his life in Alexandria, Egypt, is frequently ranked among the great poets of the early 20th century. His poetry is suffused with an ironic nostalgia for Greece's past glories. Two Greek poets have won the Nobel Prize for Literature, George Seferis (Seferis, George) in 1963 and Odysseus Elytis (Elytis, Odysseus) in 1979. The novelist best known outside Greece is the Cretan Níkos Kazantzákis (Kazantzákis, Níkos), whose Zorba the Greek was made into a popular film. A number of Greek composers have acquired an international reputation, including Nikos Skalkottas, Manos Hadjidakis, Mikis Theodorakis, and Iannis Xenakis, a French composer of Greek descent. Well-known painters in the post-World War II period include Ghika, Yannis Tsarouchis, and Photis Kontoglou, who drew his inspiration from the ascetic traditions of Byzantine art.

There is a lively theatrical tradition, in which political satire plays an important part. The traditional shadow puppet theatre, Karaghiozis, is now largely extinct, having been displaced by the ubiquitous television.

Cultural institutions

A thriving theatrical tradition is reflected in a myriad of theatres in the capital, whose repertoire ranges from Western classics to political satire. During the summer months huge audiences are attracted to performances of ancient Greek drama held in the theatre of Epidaurus, which dates from the 4th century BC and whose acoustics are extraordinary; the 2nd-century-AD Roman theatre of Herodes Atticus at the foot of the Acropolis in Athens also draws many visitors and is the location for concerts given in the framework of the annual Athens Festival held during the summer months. Live performance of orchestral music, limited in comparison with that of other European capitals, was given a major boost with the opening in 1991 of a newly built concert hall, the Megaro Mousikis (palace of music).

Given the richness of the country's archaeological heritage and the emphasis in the country's official self-perception on continuity with the classical past, the Archaeological Service has assumed particular importance. Frequently working in cooperation with the various foreign archaeological institutes, it is responsible for excavating relics of the past and for running the country's museums. Public library provision is relatively limited, and there is no adequate national library. The country's most prestigious learned society is the Academy of Athens. A distinctive feature of intellectual life is the numerous societies devoted to the study of local and regional archaeology, history, and folklore, a development that reflects the strong regional loyalties of many Greeks.

Daily life

In the hot summers social life in Greece tends to be conducted outdoors. In small towns and villages the tradition of the volta continues, when much of the population strolls up and down the main street or, on the islands, the quayside at sundown. In summer and winter much leisure time is passed in the numerous cafés and coffee shops. These latter have traditionally been a male preserve, and it is not uncommon to find in a single village one coffee shop where the adherents of one political party congregate and another for supporters of the rival party. Television and other forms of video entertainment, however, threaten to undermine traditional leisure patterns.

The country's cuisine, particularly sweets such as baklava and kataifi, reflect the influence of the centuries of Turkish rule. The food in Thessaloníki, the capital of northern Greece, which was annexed to the Greek state only in 1912, reflects the Ottoman influence and is testimony to the massive influx of refugees from Asia Minor in the 1920s. These immigrants were often facetiously referred to by the native inhabitants as yiaourtovaptismenoi (“baptized in yogurt”) on account of their fondness for yogurt in their appreciably superior cuisine. The traditional diet of the peasants was a healthy one based on vegetables, olives, olive oil, cheese, and bread, with meat being a luxury to be eaten only on special occasions. With growing affluence meat has come to assume a more important place in the country's diet, and the incidence of heart disease has risen accordingly.

Greek society is noted for its tight family structures and the low rate of crime. The extended family, and the obligation placed on family members to provide mutual support, is all-important. The centrality of the family has been little affected by the process of embourgeoisement that has been a characteristic feature of the development of Greek society in the period since the end of World War II. Although the dowry system has officially been abolished, marriages still continue to be seen to a degree as economic alliances. The great majority of the country's businesses remain small, family-run enterprises. This is also true of ship-owning, the most dynamic sector of the economy. Tightly knit clans of ship-owning families dominate this industry. The family structure of industry acts as an impediment to modernization. The wheels of society continue to be lubricated by mesa (connections) and rouspheti (the reciprocal dispensation of favours).

The main holiday periods revolve around Easter and the Feast of Dormition (Assumption) of the Virgin in mid-August. Easter is the most important religious and family festival, with many people returning to their native villages for the traditional festivities, which include the vigil in church on Saturday evening, the lighting of the Holy Fire at midnight, and the roasting of whole lambs on the spit. August is the traditional holiday month. The national sport is football (soccer), and the fortunes of the principal teams are the focus of passionate loyalties. Hunting is another popular pastime.

Press and broadcasting

During the 1980s traditional newspaper proprietors were to an extent displaced by new entrepreneurs. Most newspapers became tabloids. The circulation of morning papers declined while that of evening papers increased. Leading newspapers include Kathimerini (“Daily”), Eleftherotypia (“Free Press”), and Ethnos (“Nation”). For the most part, newspapers tend to be unashamedly partisan in their political comments, with the laws of libel inspiring little fear in publishers. The government monopoly of television and radio broadcasting was broken in the 1980s. Private television and radio stations now exist in profusion. Like the press, broadcasting is unrestrained, particularly in its handling of political issues, although often at the expense of quality.

Additional Reading

General works

All aspects of the country are treated in Glenn E. Curtis (ed.), Greece: A Country Study, 4th ed. (1995). John Campbell and Philip Sherrard, Modern Greece (1968), contains, besides useful historical surveys, valuable chapters on the Orthodox church, literature, and the economy, while paying attention to the values underpinning society. Yorgos A. Kourvetaris (George A. Kourvetaris) and Betty A. Dobratz, A Profile of Modern Greece: In Search of Identity (1987), contains material on many aspects on contemporary Greece. A good source for readings on Greece is Mary Jo Clogg and Richard Clogg (compilers), Greece (1980), a bibliography with more than 800 entries on some 30 subjects, with the majority of cited sources in English.

Physical and human geography

One of the most extensive works on the geography of Greece is Alfred Philippson, Die griechischen Landschaften, 4 vol. (1950–58). H.C. Darby et al., Greece, 3 vol. (1944–45), produced by the Naval Intelligence Division of Great Britain, contains much material of value on physical and economic geography. J.L. Myres, Dodecanese, 2nd ed. (1943), also produced by the Naval Intelligence Division, is a survey of the Dodecanese islands under Italian rule between 1912 and 1947.Greece's geology is treated in a regional context in Clifford Embleton (ed.), Geomorphology of Europe (1984), chapter 16; and Derek V. Ager, The Geology of Europe (1980), chapters 15–16. Pierre Birot and Jean Dresch, La Méditerranée et le Moyen-Orient, vol. 2, La Méditerranée Orientale et le Moyen-Orient (1955), offers details on physical structure and brief treatments of climate and vegetation. Individual aspects of the landscape are dealt with in E.G. Mariolopoulos, An Outline of the Climate of Greece (1961; originally published in Greek, 1953). J.R. McNeill, The Mountains of the Mediterranean World: An Environmental History (1992), includes the Pindus Mountains as one of the case studies. Classic studies of Greece's people and customs include Ernestine Friedl, Vasilika: A Village in Modern Greece (1962); and J.K. Campbell, Honour, Family, and Patronage: A Study of Institutions and Moral Values in a Greek Mountain Community (1964, reissued 1974). Michael Kenny and David I. Kertzer (eds.), Urban Life in Mediterranean Europe (1983), includes several essays on Greece, including a study of rural-urban migration. Timothy Ware (Kallistos Ware), The Orthodox Church, new ed. (1993), is a clear and concise account of the history and theology of the predominant religion in Greece.The economy is covered by A.F. Freris, The Greek Economy in the Twentieth Century (1986); and Persefoni V. Tsaliki, The Greek Economy: Sources of Growth in the Postwar Era (1991). Politics is dealt with in Keith R. Legg, Politics in Modern Greece (1969); and Richard Clogg, Parties and Elections in Greece (1987).The remarkable continuities in the Greek language are discussed in Robert Browning, Medieval and Modern Greek, 2nd ed. (1983). A comprehensive survey, beginning with the emergence in the 11th century AD of literature in a recognizably modern form of the language, is Linos Politis (Linos Polités), A History of Modern Greek Literature (1973).

- bell hooks

- Belli, Carlos Germán

- belligerency

- Belli, Giuseppe Gioacchino

- Bellingham

- Bellingshausen, Fabian Gottlieb von

- Bellini, Gentile

- Bellini, Giovanni

- Bellini, Jacopo

- Bellini, Lorenzo

- Bellini, Vincenzo

- Bellinzona

- Belli, Pierino

- Bell Island

- Bell, John

- Bell, Josephine

- Bell Laboratories

- Bell, Lawrence Dale

- bell-magpie

- Bellman, Carl Michael

- Bello

- Bello, Andrés

- Belloc, Hilaire

- Bellona

- Bellotto, Bernardo