Greek religion

ancient religion

Introduction

religious beliefs and practices of the ancient Hellenes. Greek religion is not the same as Greek mythology, which is concerned with traditional tales, though the two are closely interlinked. Curiously, for a people so religiously minded, the Greeks had no word for religion itself; the nearest terms were eusebeia (“piety”) and threskeia (“cult”).

religious beliefs and practices of the ancient Hellenes. Greek religion is not the same as Greek mythology, which is concerned with traditional tales, though the two are closely interlinked. Curiously, for a people so religiously minded, the Greeks had no word for religion itself; the nearest terms were eusebeia (“piety”) and threskeia (“cult”).Although its origins may be traced to the remotest eras, Greek religion in its developed form lasted more than a thousand years, from the time of Homer (probably 9th or 8th century BC) to the reign of the emperor Julian (4th century AD). During that period its influence spread as far west as Spain, east to the Indus River, and throughout the Mediterranean world. Its effect was most marked on the Romans, who identified their deities with those of the Greeks. Under Christianity, Greek heroes and even deities survived as saints, while the rival madonnas of southern European communities reflected the independence of local cults. The rediscovery of Greek literature during the Renaissance and, above all, the novel perfection of Classical sculpture produced a revolution in taste that had far-reaching effects on Christian religious art. The most striking characteristic of Greek religion was the belief in a multiplicity of anthropomorphic deities under one supreme god. Priests simply looked after cults; they did not constitute a clergy, and there were no sacred books.

The sole requirements for the Greeks were to believe that the gods existed and to perform ritual and sacrifice, through which the gods received their due. To deny the existence of a deity was to risk reprisals, from the deity or from other mortals. The list of avowed atheists is brief. But if a Greek went through the motions of piety, he risked little, since no attempt was made to enforce orthodoxy, a religious concept almost incomprehensible to the Greeks. The large corpus of myths concerned with gods, heroes, and rituals embodied the worldview of Greek religion and remains its legacy. (See Greek mythology.) It should be noted that the myths varied over time and that, within limits, a writer—e.g., a Greek tragedian—could alter a myth by changing not only the role played by the gods in it but also the evaluation of the gods' actions.

From the later 6th century BC onward, myths and gods were subject to rational criticism on ethical or other grounds. In these circumstances it is easy to overlook the fact that most Greeks “believed” in their gods in roughly the modern sense of the term and that they prayed in a time of crisis not merely to the “relevant” deity but to any deity on whose aid they had established a claim by sacrifice. To this end, each Greek polis had a series of public festivals throughout the year that were intended to ensure the aid of all the gods who were thus honoured. They reminded the gods of services rendered and asked for a quid pro quo. Particularly during times of crises, the Greeks, like the Romans, were often willing to petition deities borrowed from other cultures.

History

The roots of Greek religion

The study of a religion's history includes the study of the history of those who espoused it, together with their spiritual, ethical, political, and intellectual experiences. Greek religion as it is currently understood probably resulted from the mingling of religious beliefs and practices between the incoming Greek-speaking peoples who arrived from the north during the 2nd millennium BC and the indigenous inhabitants whom they called Pelasgi. The incomers' pantheon was headed by the Indo-European sky god variously known as Zeus (Greek), Dyaus (Indian), or Jupiter (Roman). But there was also a Cretan sky god, whose birth and death were celebrated in rituals and myths quite different from those of the incomers. The incomers applied the name of Zeus to his Cretan counterpart. In addition, there was a tendency, fostered but not necessarily originated by Homer and Hesiod, for major Greek deities to be given a home on Mount Olympus (Olympus, Mount). Once established there in a conspicuous position, the Olympians came to be identified with local deities and to be assigned as consorts to the local god or goddess.

The study of a religion's history includes the study of the history of those who espoused it, together with their spiritual, ethical, political, and intellectual experiences. Greek religion as it is currently understood probably resulted from the mingling of religious beliefs and practices between the incoming Greek-speaking peoples who arrived from the north during the 2nd millennium BC and the indigenous inhabitants whom they called Pelasgi. The incomers' pantheon was headed by the Indo-European sky god variously known as Zeus (Greek), Dyaus (Indian), or Jupiter (Roman). But there was also a Cretan sky god, whose birth and death were celebrated in rituals and myths quite different from those of the incomers. The incomers applied the name of Zeus to his Cretan counterpart. In addition, there was a tendency, fostered but not necessarily originated by Homer and Hesiod, for major Greek deities to be given a home on Mount Olympus (Olympus, Mount). Once established there in a conspicuous position, the Olympians came to be identified with local deities and to be assigned as consorts to the local god or goddess. An unintended consequence (since the Greeks were monogamous) was that Zeus in particular became markedly polygamous. (Zeus already had a consort when he arrived in the Greek world and took Hera, herself a major goddess in Argos, as another.) Hesiod used—or sometimes invented—the family links among the deities, traced out over several generations, to explain the origin and present condition of the universe. At some date, Zeus and other deities were identified locally with heroes and heroines from the Homeric poems and called by such names as Zeus Agamemnon. The Pelasgian and the Greek strands of the religion of the Greeks can sometimes be disentangled, but the view held by some scholars that any belief related to fertility must be Pelasgian, on the grounds that the Pelasgi were agriculturalists while the Greeks were nomadic pastoralists and warriors, seems somewhat simplistic. Pastoralists and warriors certainly require fertility in their herds—not to mention in their own number.

An unintended consequence (since the Greeks were monogamous) was that Zeus in particular became markedly polygamous. (Zeus already had a consort when he arrived in the Greek world and took Hera, herself a major goddess in Argos, as another.) Hesiod used—or sometimes invented—the family links among the deities, traced out over several generations, to explain the origin and present condition of the universe. At some date, Zeus and other deities were identified locally with heroes and heroines from the Homeric poems and called by such names as Zeus Agamemnon. The Pelasgian and the Greek strands of the religion of the Greeks can sometimes be disentangled, but the view held by some scholars that any belief related to fertility must be Pelasgian, on the grounds that the Pelasgi were agriculturalists while the Greeks were nomadic pastoralists and warriors, seems somewhat simplistic. Pastoralists and warriors certainly require fertility in their herds—not to mention in their own number.The Archaic period

The name Dionysus occurs in the Linear B (Linear A and Linear B) tablets, so it seems very likely that his worship was a part of Mycenaean religion. His devotees, armed with thyrsoi (wands tipped with a pinecone and wreathed with grapevine or ivy leaves) and known as maenads (literally “mad women”), were reputed to wander in thiasoi (revel bands) about mountain slopes, such as Cithaeron or Parnassus; the practice persisted into Roman imperial times. They were also supposed, in their ecstasy, to practice the sparagmos, the tearing of living victims to pieces and feasting on their raw flesh (ōmophagia). While such behaviour continued in the wild, in the cities—in Athens, at any rate—the cult of Dionysus was tamed before 500 BC. tragedy developed from the choral song of Dionysus.

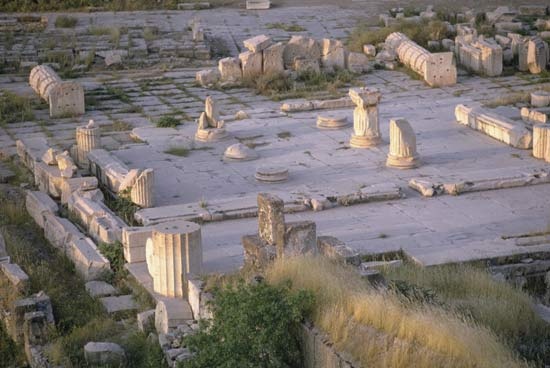

The name Dionysus occurs in the Linear B (Linear A and Linear B) tablets, so it seems very likely that his worship was a part of Mycenaean religion. His devotees, armed with thyrsoi (wands tipped with a pinecone and wreathed with grapevine or ivy leaves) and known as maenads (literally “mad women”), were reputed to wander in thiasoi (revel bands) about mountain slopes, such as Cithaeron or Parnassus; the practice persisted into Roman imperial times. They were also supposed, in their ecstasy, to practice the sparagmos, the tearing of living victims to pieces and feasting on their raw flesh (ōmophagia). While such behaviour continued in the wild, in the cities—in Athens, at any rate—the cult of Dionysus was tamed before 500 BC. tragedy developed from the choral song of Dionysus. In the 7th and 6th centuries BC “tyrants” (monarchs whose position was not derived from heredity) seized power in many poleis. Some tyrants, such as Peisistratus in Athens, were nobles and rose to power by offering the poor defense against the rest of the nobility. Once established, Peisistratus built temples and founded or revived festivals. At this time too, the earliest references to the Eleusinian Mysteries appear. The Mysteries offered a more personal, less distant relationship with the divine than did most of the Olympians. There was no Eleusinian way of life. On one or two occasions (depending on the grade they wished to attain) the initiates went to Eleusis; what they saw there in the place of initiation sufficed to ensure them a life after death that was much more “real” than the afterlife portrayed in the Olympian belief that the dead were witless ghosts.

In the 7th and 6th centuries BC “tyrants” (monarchs whose position was not derived from heredity) seized power in many poleis. Some tyrants, such as Peisistratus in Athens, were nobles and rose to power by offering the poor defense against the rest of the nobility. Once established, Peisistratus built temples and founded or revived festivals. At this time too, the earliest references to the Eleusinian Mysteries appear. The Mysteries offered a more personal, less distant relationship with the divine than did most of the Olympians. There was no Eleusinian way of life. On one or two occasions (depending on the grade they wished to attain) the initiates went to Eleusis; what they saw there in the place of initiation sufficed to ensure them a life after death that was much more “real” than the afterlife portrayed in the Olympian belief that the dead were witless ghosts.The Classical period

During the 6th century BC the rationalist thinking of Ionian (Ionian school) philosophers had offered a serious challenge to traditional religion. At the beginning of the 5th century, Heracleitus of Ephesus and Xenophanes of Colophon heaped scorn on cult and gods alike.

The Sophists (Sophist), with their relentless probing of accepted values, continued the process. Little is known of the general success of these attacks in society as a whole. The Parthenon and other Athenian temples of the late 5th century proclaim the taste and power of the Athenians rather than their awe of the gods; but, it is said, after the completion of Phidias's chryselephantine (gold and ivory) Athena on the Acropolis, the old olive-wood statue of Athena, aesthetically no match for Phidias's work, continued to receive the worship of most of the citizens. Antiquity evoked awe; some of the most revered objects in Greece were antique and aniconic figures that bore the name of an Olympian deity.

The Sophists (Sophist), with their relentless probing of accepted values, continued the process. Little is known of the general success of these attacks in society as a whole. The Parthenon and other Athenian temples of the late 5th century proclaim the taste and power of the Athenians rather than their awe of the gods; but, it is said, after the completion of Phidias's chryselephantine (gold and ivory) Athena on the Acropolis, the old olive-wood statue of Athena, aesthetically no match for Phidias's work, continued to receive the worship of most of the citizens. Antiquity evoked awe; some of the most revered objects in Greece were antique and aniconic figures that bore the name of an Olympian deity. Festivals (feast) were expressive of religion's social aspect and attracted large gatherings (panēgyreis (panegyris)). Mainly agrarian in origin, they were seasonal in character, held often at full moon and on the 7th of the month in the case of Apollo and always with a sacrifice in view. Many were older than the deity they honoured, like the Hyacinthia and Carneia in Laconia, which were transferred from local heroes to Apollo. The games were a special festival, sometimes part of other religious events. Some festivals of Athens were performed on behalf of the polis and all its members. Many of these seem to have been originally the cults of individual noble families who came together at the synoikismos, the creation of the polis of Athens from its small towns and villages. The nobles continued to furnish the priests for these cults, but there was, and could be, no priestly class. There were no “priests of the gods” or even priests of an individual god; one became a priest of one god at one temple. Except for these public festivals, anyone might perform a sacrifice at any time. The priest's role was to keep the temple clean; he was usually guaranteed some part of the animal sacrificed. A priesthood offered a reasonably secure living to its incumbent.

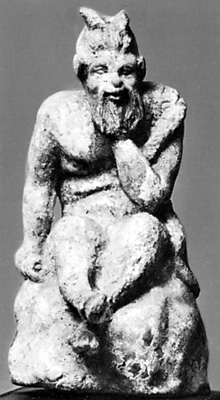

Festivals (feast) were expressive of religion's social aspect and attracted large gatherings (panēgyreis (panegyris)). Mainly agrarian in origin, they were seasonal in character, held often at full moon and on the 7th of the month in the case of Apollo and always with a sacrifice in view. Many were older than the deity they honoured, like the Hyacinthia and Carneia in Laconia, which were transferred from local heroes to Apollo. The games were a special festival, sometimes part of other religious events. Some festivals of Athens were performed on behalf of the polis and all its members. Many of these seem to have been originally the cults of individual noble families who came together at the synoikismos, the creation of the polis of Athens from its small towns and villages. The nobles continued to furnish the priests for these cults, but there was, and could be, no priestly class. There were no “priests of the gods” or even priests of an individual god; one became a priest of one god at one temple. Except for these public festivals, anyone might perform a sacrifice at any time. The priest's role was to keep the temple clean; he was usually guaranteed some part of the animal sacrificed. A priesthood offered a reasonably secure living to its incumbent.Popular religion flourished alongside the civic cults. Peasants worshipped the omnipresent deities of the countryside, such as the Arcadian goat-god pan, who prospered the flocks, and the nymphs (who, like Eileithyia, aided women in childbirth) who inhabited caves, springs (Naiads), trees (dryads and hamadryads), and the sea (Nereids). They also believed in nature spirits such as satyrs and sileni and equine Centaurs. Among the more popular festivals were the rural Dionysia (Bacchanalia), which included a phallus pole; the Anthesteria, when new wine was broached and offerings were made to the dead; the Thalysia, a harvest celebration; the Thargelia, when a scapegoat (pharmakos) assumed the communal guilt; and the Pyanepsia (Pyanopsia), a bean feast in which boys collected offerings to hang on the eiresiōne (“wool pole”). Women celebrated the Thesmophoria in honour of Demeter and commemorated the passing of Adonis with laments and miniature gardens, while images were swung from trees at the Aiora. magic was widespread. Spells were inscribed on lead tablets. Statues of Hecate, goddess of witchcraft, stood outside dwellings, while Pan's image was beaten with herbs in times of meat shortage.

The Hellenistic period

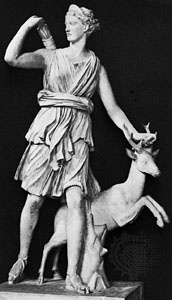

Greek religion, having no creed, did not proselytize. In the heyday of the polis, the Greek religion was spread by the founding of new poleis, whose colonists took with them part of the sacred fire from the hearth of the mother city and the cults of the city's gods. (“Heroes,” being essentially bound to the territory in which they were buried, had to be left behind.) There was a tendency for Greeks to identify the gods of others with their own, often at a superficial level. So the virgin Artemis was identified with the chief goddess of Ephesus, a fertility deity.

Greek religion, having no creed, did not proselytize. In the heyday of the polis, the Greek religion was spread by the founding of new poleis, whose colonists took with them part of the sacred fire from the hearth of the mother city and the cults of the city's gods. (“Heroes,” being essentially bound to the territory in which they were buried, had to be left behind.) There was a tendency for Greeks to identify the gods of others with their own, often at a superficial level. So the virgin Artemis was identified with the chief goddess of Ephesus, a fertility deity.After Alexander the Great had created a political world in which the poleis were engulfed by large kingdoms, those deities who were not too closely linked with a particular place became more prominent. Mystery (mystery religion) cults, which offered a personal value to the individual in a large and indifferent world, also flourished. The Cabeiri of Samothrace, deities that had come in from Asia, were patronized by both the Greeks and the Romans, while the Egyptian cults of Isis and Serapis, in a Hellenized form, spread widely.

Rulers sometimes officially invited new gods to settle in times of crisis, in the hope that they would strive on their new worshippers' behalf against their mortal foes; this mode of religious thought flourished at least until the days of the Roman emperor Constantine. Those novel cults that seemed likely to pose a threat to public order, on the other hand, were suppressed by the Romans. The Senate destroyed the Bacchic cult in Italy in 186 BC, perhaps for the same reasons that the emperor Trajan gave to the writer and statesman Pliny the Younger for his treatment of the Christians: any cult in which men and women, bond and free, could participate and meet together—a most unusual circumstance in the ancient world—had dangerous political implications.

Beliefs, practices, and institutions

The gods

The early Greeks personalized every aspect of their world, natural and cultural, and their experiences in it. The earth, the sea, the mountains, the rivers, custom-law (themis), and one's share in society and its goods were all seen in personal as well as naturalistic terms. When Achilles fights with the River in the Iliad, the River speaks to Achilles but uses against him only such weapons as are appropriate to a stream of water. In Hesiod what could be distinguished as anthropomorphic (anthropomorphism) deities and personalizations of natural or cultural phenomena both beget and are begotten by each other. Hera is of the first type—goddess of marriage but not identified with marriage. Earth is evidently of the second type, as are, in a somewhat different sense, Eros and Aphrodite (god and goddess of sexual desire) and Ares (god of war). These latter are personalized and anthropomorphized, but their worshippers may be “filled” with them. Some deities have epithets that express a particular aspect of their activities. Zeus is known as Zeus Xenios in his role as guarantor of guests. It is possible that Xenios was originally an independent deity, absorbed by Zeus as a result of the Olympo-centric tendencies of Greek religion encouraged by the poems of Homer and Hesiod.

The early Greeks personalized every aspect of their world, natural and cultural, and their experiences in it. The earth, the sea, the mountains, the rivers, custom-law (themis), and one's share in society and its goods were all seen in personal as well as naturalistic terms. When Achilles fights with the River in the Iliad, the River speaks to Achilles but uses against him only such weapons as are appropriate to a stream of water. In Hesiod what could be distinguished as anthropomorphic (anthropomorphism) deities and personalizations of natural or cultural phenomena both beget and are begotten by each other. Hera is of the first type—goddess of marriage but not identified with marriage. Earth is evidently of the second type, as are, in a somewhat different sense, Eros and Aphrodite (god and goddess of sexual desire) and Ares (god of war). These latter are personalized and anthropomorphized, but their worshippers may be “filled” with them. Some deities have epithets that express a particular aspect of their activities. Zeus is known as Zeus Xenios in his role as guarantor of guests. It is possible that Xenios was originally an independent deity, absorbed by Zeus as a result of the Olympo-centric tendencies of Greek religion encouraged by the poems of Homer and Hesiod.In Homer the gods constitute essentially a super-aristocracy. The worshippers of these gods do not believe in reward or punishment after death; one's due must come in this life. Every success shows that the gods are well disposed, for the time being at least; every failure shows that some god is angry, usually as a result of a slight, intended or unintended, rather than from the just or unjust behaviour of one mortal to another. The Greeks knew what angered their mortal aristocracy and extrapolated from there. Prayer and sacrifice, however abundant, could not guarantee that the gods would grant success. The gods might prefer peace on Olympus to helping their worshippers. These are not merely literary fictions; they reflect the beliefs of people who knew that though it might be necessary to offer prayer and sacrifice to the gods, it was not sufficient. Greeks and Trojans sacrificed to their gods to ensure divine support in war and at other times of crisis. It was believed that Zeus, the strongest of the gods, had favoured the Trojans, while Hera had favoured the Greeks. Yet Troy fell, like many another city. The Homeric poems here offer an explanation for something that the Greek audience might at any time experience themselves.

There is no universal determinism in Homer or in other early writers. Moira (Fate) (“share”) denotes one's earthly portion, all the attributes, possessions, goods, or ills that together define one's position in society. Homeric society is stratified, from Zeus to the meanest beggar. To behave in accordance with one's share is to behave in accordance with one's status; even a beggar may go beyond his share, though he is likely to be punished for it. Zeus, the most powerful entity in Homer's universe, certainly has the power to go beyond his share; but if he does so, the other gods will not approve. And Zeus may be restrained, unless he feels that his “excellence,” his ability to perform the action, is being called into question. Then he may insist on displaying his excellence, as do Achilles and Agamemnon, whose values coincide with those of Zeus in such matters.

In Homer, hērōī denotes the greatest of the living warriors. The cults of these mighty men developed later around their tombs. Heroes (hero) were worshipped as the most powerful of the dead, who were able, if they wished, to help the inhabitants of the polis in which their bones were buried. Thus, the Spartans brought back the bones of Orestes from Tegea. Historical characters might be elevated to the status of heroes at their deaths. During the Peloponnesian War, the inhabitants of Amphipolis heroized the Spartan general Brasidas, who had fought so well and bravely and died in their defense. It is power, not righteousness, that distinguishes the hero; it is the feeling of awe before the old, blind Oedipus that stimulates the Thebans and the Athenians to quarrel over his place of burial. Since they are the mightiest of the dead, heroes receive offerings suitable for chthonic (underworld) deities.

In Homer, hērōī denotes the greatest of the living warriors. The cults of these mighty men developed later around their tombs. Heroes (hero) were worshipped as the most powerful of the dead, who were able, if they wished, to help the inhabitants of the polis in which their bones were buried. Thus, the Spartans brought back the bones of Orestes from Tegea. Historical characters might be elevated to the status of heroes at their deaths. During the Peloponnesian War, the inhabitants of Amphipolis heroized the Spartan general Brasidas, who had fought so well and bravely and died in their defense. It is power, not righteousness, that distinguishes the hero; it is the feeling of awe before the old, blind Oedipus that stimulates the Thebans and the Athenians to quarrel over his place of burial. Since they are the mightiest of the dead, heroes receive offerings suitable for chthonic (underworld) deities.Cosmogony

Of several competing cosmogonies in Archaic Greece, Hesiod's Theogony is the only one that has survived in more than fragments. It records the generations of the gods from Chaos (literally, “Yawning Gap”) through Zeus and his contemporaries to the gods who had two divine parents (e.g., Apollo and Artemis, born of Zeus and Leto) and the mortals who had one divine parent (e.g., Heracles, born of Zeus and Alcmene). Hesiod uses the relationships of the deities, by birth, marriage, or treaty, to explain why the world is as it is and why Zeus, the third supreme deity of the Greeks, has succeeded in maintaining his supremacy—thus far—where his predecessors failed. Essentially, Zeus is a better politician and has the balance of power, practical wisdom, and good counsel on his side. (Whether Hesiod or some earlier thinker produced this complex nexus of relationships, with which Hesiod could account for virtually anything that had occurred or might occur in the future, the grandeur of this intellectual achievement should not be overlooked.)

Mortals

In the period in Greece between Homer and about 450 BC the language of relationships between god and god, mortal and god, and lower-status mortal with higher-status mortal was the same. The deities remained a super-aristocracy. There was a scale of power and excellence on which the position of every mortal and every deity could be plotted. Both god and mortal were likely to resent any attempt of an inferior to move higher on the scale. It constituted hybris (hubris) (“overweening pride,” or hubris) for a Greek hērōs to claim that he would have a safe voyage whether or not the gods were willing; it was likewise hubris for Electra to presume to criticize the behaviour of her mother, Clytemnestra.

In the period in Greece between Homer and about 450 BC the language of relationships between god and god, mortal and god, and lower-status mortal with higher-status mortal was the same. The deities remained a super-aristocracy. There was a scale of power and excellence on which the position of every mortal and every deity could be plotted. Both god and mortal were likely to resent any attempt of an inferior to move higher on the scale. It constituted hybris (hubris) (“overweening pride,” or hubris) for a Greek hērōs to claim that he would have a safe voyage whether or not the gods were willing; it was likewise hubris for Electra to presume to criticize the behaviour of her mother, Clytemnestra. A further reason for Olympian disapproval, only marginally present in Homer, was the pollution caused by certain actions and experiences, such as childbirth, death, or having a bad dream. The divine world of the Greeks was bisected by a horizontal line. Above that line were the Olympians, gods of life, daylight, and the bright sky; and below it were the chthonic gods of the dead and of the mysterious fertility of the earth. The Olympians kept aloof from the underworld gods and from those who should be in their realm: Creon is punished in Sophocles' Antigone by the Olympians for burying Antigone alive, for she is still “theirs,” and for failing to bury the dead Polyneices, gobbets of whose flesh are polluting their altars; and Artemis abandons Hippolytus, her most ardent worshipper, as his death approaches, for all corpses pollute. Pollution was not a moral concept, and it further complicated relationships between the Greeks and their gods.

A further reason for Olympian disapproval, only marginally present in Homer, was the pollution caused by certain actions and experiences, such as childbirth, death, or having a bad dream. The divine world of the Greeks was bisected by a horizontal line. Above that line were the Olympians, gods of life, daylight, and the bright sky; and below it were the chthonic gods of the dead and of the mysterious fertility of the earth. The Olympians kept aloof from the underworld gods and from those who should be in their realm: Creon is punished in Sophocles' Antigone by the Olympians for burying Antigone alive, for she is still “theirs,” and for failing to bury the dead Polyneices, gobbets of whose flesh are polluting their altars; and Artemis abandons Hippolytus, her most ardent worshipper, as his death approaches, for all corpses pollute. Pollution was not a moral concept, and it further complicated relationships between the Greeks and their gods. eschatology

In Homer only the gods were by nature immortal, but Elysium was reserved for their favoured sons-in-law, whom they exempted from death. Heracles alone gained a place on Olympus by his own efforts. The ordinary hero hated death, for the dead were regarded as strengthless doubles who had to be revived with drafts of blood, mead, wine, and water in order to enable them to speak. They were conducted, it was believed, to the realm of Hades by Hermes; but the way was barred, according to popular accounts, by the marshy river Styx. Across this, Charon ferried all who had received at least token burial, and coins were placed in the mouths of corpses to pay the fare.

Originally, only great sinners like Ixion, Sisyphus, and Tityus, who had offended the gods personally, were punished in Tartarus. But the doctrines of the Orphics influenced the lyric poet Pindar, the philosopher Empedocles, and, above all, Plato. According to the latter, the dead were judged in a meadow by Aeacus, Minos, and Rhadamanthus and were consigned either to Tartarus or to the Isles of the Blest. Long periods of purgation were required before the wicked could regain their celestial state, while some were condemned forever. The dead were permitted to choose lots for their next incarnation. Subsequently they drank from the stream of Lethe, the river of oblivion, and forgot all of their previous experiences. (See also Orpheus; mystery religion: History (mystery religion)).

Originally, only great sinners like Ixion, Sisyphus, and Tityus, who had offended the gods personally, were punished in Tartarus. But the doctrines of the Orphics influenced the lyric poet Pindar, the philosopher Empedocles, and, above all, Plato. According to the latter, the dead were judged in a meadow by Aeacus, Minos, and Rhadamanthus and were consigned either to Tartarus or to the Isles of the Blest. Long periods of purgation were required before the wicked could regain their celestial state, while some were condemned forever. The dead were permitted to choose lots for their next incarnation. Subsequently they drank from the stream of Lethe, the river of oblivion, and forgot all of their previous experiences. (See also Orpheus; mystery religion: History (mystery religion)).Sacred writings

Greek religion was not based on a written creed or body of dogma. Nevertheless, certain sacred writings survive in the form of hymns, oracles, inscriptions, and instructions to the dead. Most elaborate are the Homeric Hymns, some of which may have been composed for religious festivals, though their subject matter is almost entirely mythological. Delphic inscriptions include hymns to Apollo but, like the Epidaurian hymn by Isyllus to Asclepius, they are not concerned with liturgy. Delphic oracles are quoted from literary sources but appear, on the whole, to be retrospective concoctions, like the Hebraic-Hellenistic collection of Sibylline prophecies. Questions scratched on folded lead tablets have been found at Dodona, and detailed instructions to the dead, inscribed on gold leaf and possibly of Orphic inspiration, have been found in Greek graves in southern Italy. Papyrus fragments of similar character have been recovered from graves in Macedonia and Thessaly.

Shrines and temples

In the earliest times deities were worshipped in awesome places such as groves, caves, or mountaintops. Mycenaean deities shared the king's palace. Fundamental was the precinct (temenos) allotted to the deity, containing the altar, temple (if any), and other sacral or natural features, such as the sacred olive in the temenos of Pandrosos on the Athenian Acropolis. Naoi (temples—literally “dwellings”—that housed the god's image) were already known in Homeric times and, like models discovered at Perachora, were wooden and of simple design. Poros and marble replaced wood by the end of the 7th century BC, when temples became large and were constructed with rows of columns on all sides. The image, crude and wooden at first, was placed in the central chamber ( cella), which was open at the eastern end. No ritual was associated with the image itself, though it was sometimes paraded. Hero shrines were far less elaborate and had pits for offerings. Miniature shrines also were known.

In the earliest times deities were worshipped in awesome places such as groves, caves, or mountaintops. Mycenaean deities shared the king's palace. Fundamental was the precinct (temenos) allotted to the deity, containing the altar, temple (if any), and other sacral or natural features, such as the sacred olive in the temenos of Pandrosos on the Athenian Acropolis. Naoi (temples—literally “dwellings”—that housed the god's image) were already known in Homeric times and, like models discovered at Perachora, were wooden and of simple design. Poros and marble replaced wood by the end of the 7th century BC, when temples became large and were constructed with rows of columns on all sides. The image, crude and wooden at first, was placed in the central chamber ( cella), which was open at the eastern end. No ritual was associated with the image itself, though it was sometimes paraded. Hero shrines were far less elaborate and had pits for offerings. Miniature shrines also were known.Most oracular shrines included a subterranean chamber, but no trace of such has been found at Delphi, though the Pythia was always said to “descend.” At the oracle of Trophonius, discovered in 1967 at Levádhia, incubation (ritual sleep to induce a dream) was practiced in a hole. The most famous centre of incubation was that of Asclepius at Epidaurus. His temple was furnished with a hall where the sick were advised by the demigod in dreams. divination was also widely practiced in Greece. Augurs (augury) interpreted the flight of birds, while dreams and even sneezes were regarded as ominous. Seers also divined from the shape of altar smoke and the conformation of sacrificial animals' entrails.

priesthood

Even in the state cults, priesthoods were frequently ancestral prerogatives. Eteobutads organized the cult of the hero-king Erechtheus at Athens; Praxiergids superintended the washing of Athena's robes at the Plynteria; and Clytiads and Iamids officiated at the altar of Zeus at Olympia. Although there was no official clergy, since the religious and secular spheres were not sharply divided, professional assistance was available at sacrifices. There was no necessary correspondence between the sex of deities and that of priests. Hera and Athena favoured priestesses, but Isis and Cybele favoured priests. Apollo inspired the Pythia (priestess) at Delphi but a priest at Ptoon. The mysteries at Eleusis were administered by the Eumolpids and Kerykes. The latter assembled the initiates (mystae), while the former provided the Hierophant, who revealed the mysteries in the torch-lit Anaktoron (king's shrine) within the great Telesterion, or entrance hall.

Festivals (feast)

The precise details of many festivals are obscure. Among the more elaborate was the Panathenaea, which was celebrated at high summer; every fourth year it was celebrated on a more splendid scale (the Great Panathenaea). Its purpose, besides offering sacrifice, was to provide the ancient wooden image of Athena, housed in the “Old Temple,” with a new robe woven by the wives of Athenian citizens. The Great Panathenaea included a procession, a torch race, athletic contests, mock fights, and bardic recitations. The Great Dionysia was celebrated at Athens in spring. At the end of the ritual the god's image was escorted to the theatre of Dionysus, where it presided over the dramatic contests. It, like its rural counterpart, included phallic features.

The precise details of many festivals are obscure. Among the more elaborate was the Panathenaea, which was celebrated at high summer; every fourth year it was celebrated on a more splendid scale (the Great Panathenaea). Its purpose, besides offering sacrifice, was to provide the ancient wooden image of Athena, housed in the “Old Temple,” with a new robe woven by the wives of Athenian citizens. The Great Panathenaea included a procession, a torch race, athletic contests, mock fights, and bardic recitations. The Great Dionysia was celebrated at Athens in spring. At the end of the ritual the god's image was escorted to the theatre of Dionysus, where it presided over the dramatic contests. It, like its rural counterpart, included phallic features. The Olympic Games formed part of the great festival of Zeus held every fourth summer in the god's sacred precinct—the Altis beside the river Alpheius in the western Peloponnese. A truce was proclaimed in order to permit any warring Greeks to compete, and the celebrations lasted five days. Sacrifice and libation were made at the altar of Zeus, where omens were taken and oracles proclaimed, and at the tomb of Pelops and the altar of Hestia. Competitors and judges took an oath to observe the rules; processions were held; bards recited; and winners were honoured at state banquets. The richer and more famous were immortalized by lyric poets, such as Simonides, Bacchylides, and Pindar. Though women were banned, girls competed at the festival of Hera. The games held in honour of Zeus at Nemea, Apollo at Delphi, and Poseidon at the Isthmus followed the Olympian pattern.

The Olympic Games formed part of the great festival of Zeus held every fourth summer in the god's sacred precinct—the Altis beside the river Alpheius in the western Peloponnese. A truce was proclaimed in order to permit any warring Greeks to compete, and the celebrations lasted five days. Sacrifice and libation were made at the altar of Zeus, where omens were taken and oracles proclaimed, and at the tomb of Pelops and the altar of Hestia. Competitors and judges took an oath to observe the rules; processions were held; bards recited; and winners were honoured at state banquets. The richer and more famous were immortalized by lyric poets, such as Simonides, Bacchylides, and Pindar. Though women were banned, girls competed at the festival of Hera. The games held in honour of Zeus at Nemea, Apollo at Delphi, and Poseidon at the Isthmus followed the Olympian pattern.Rites

sacrifice was offered to the Olympian deities at dawn at the altar in the temenos, which normally stood east of the temple. Representing as it did a gift to the gods, sacrifice constituted the principal proof of piety. The gods were content with the burnt portion of the offering, while the priests and worshippers shared the remainder of the meat. Different animals were sacred to different deities—e.g., heifers to Athena, cows to Hera, pigs to Demeter, bulls to Zeus and Dionysus, dogs to Hecate, game and heifers to Artemis, horses to Poseidon, and asses to Priapus—though the distinctions were not rigorously observed. The practices of ritual washing before sacrifice, sprinkling barley grains, and making token offerings of hair are described by Homer. Victims were required to be free of blemish, or they were likely to offend the deity. Sacrifice also was made to chthonian powers in the evening. Black-coloured animal victims were offered and placed in pits, and the meat was entirely consumed. Sacrifice preceded battles, treaties, or similar events. Human sacrifice appears, if it was practiced at all, to have been the exception. Bloodless sacrifices were made to some deities and heroes.

sacrifice was offered to the Olympian deities at dawn at the altar in the temenos, which normally stood east of the temple. Representing as it did a gift to the gods, sacrifice constituted the principal proof of piety. The gods were content with the burnt portion of the offering, while the priests and worshippers shared the remainder of the meat. Different animals were sacred to different deities—e.g., heifers to Athena, cows to Hera, pigs to Demeter, bulls to Zeus and Dionysus, dogs to Hecate, game and heifers to Artemis, horses to Poseidon, and asses to Priapus—though the distinctions were not rigorously observed. The practices of ritual washing before sacrifice, sprinkling barley grains, and making token offerings of hair are described by Homer. Victims were required to be free of blemish, or they were likely to offend the deity. Sacrifice also was made to chthonian powers in the evening. Black-coloured animal victims were offered and placed in pits, and the meat was entirely consumed. Sacrifice preceded battles, treaties, or similar events. Human sacrifice appears, if it was practiced at all, to have been the exception. Bloodless sacrifices were made to some deities and heroes. Prayers (prayer) normally began with compliments to the deity, followed by discreet references to the petitioner's piety, and ended with his special plea. In addressing a prayer to an Olympian, the suppliant stood with his arms raised and palms upward. Processions (procession) formed part of most gatherings (panēgyreis) and festivals. The Panathenaic procession set out from the Pompeion (sacred storehouse) at dawn, headed by maiden basket-bearers (kanēphoroi) who carried the sacred panoply. Elders bore boughs (thallophoroi) while youths (ephēboi) conducted the victims for sacrifice, and cavalry brought up the rear. The robe was spread on the mast of a wheeled ship.

Prayers (prayer) normally began with compliments to the deity, followed by discreet references to the petitioner's piety, and ended with his special plea. In addressing a prayer to an Olympian, the suppliant stood with his arms raised and palms upward. Processions (procession) formed part of most gatherings (panēgyreis) and festivals. The Panathenaic procession set out from the Pompeion (sacred storehouse) at dawn, headed by maiden basket-bearers (kanēphoroi) who carried the sacred panoply. Elders bore boughs (thallophoroi) while youths (ephēboi) conducted the victims for sacrifice, and cavalry brought up the rear. The robe was spread on the mast of a wheeled ship.The procession to Eleusis to restore the sacred objects, brought by the ephēboi to the Eleusinium sometime previously, followed the wooden image of Iacchus (a personification of the ritual cry), which was escorted by its own priest, the iacchagogos, and officials. The mystae wore myrtle crowns and carried sheaves of grain. Whatever the nature of the mysteries, those initiated returned in a mood of exaltation. Adepts (epoptai) were later admitted to more solemn rites (to see an ear of wheat, scoffers said).

Religious art and iconography

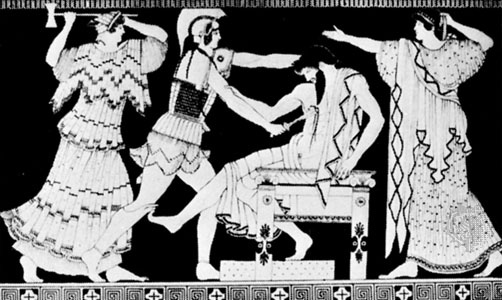

Art often portrays incidents relevant to the study of Greek religion, but frequently essential information is missing. On a well-known sarcophagus from Ayías Triádhos in Crete, for example, a priestess dressed in a skin skirt assists at a sacrifice, flanked by wreathed axes on which squat birds. The significance of the scene has been much discussed. The birds have been regarded as epiphanies of deities, giving sacral meaning to the transformations in Homer. Again, since goddesses appear to preponderate in Minoan-Mycenaean art, while male deities are represented on an inferior scale, this has been thought to reflect the general superiority of goddesses in many parts of Greece.

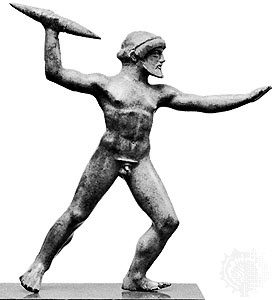

In the earliest period, terra-cotta statuettes (sculpture) of deities were small and crude, while the old cult images were made of wood and commonly attributed to Daedalus. When artists turned to bronze and marble, they depicted the anthropomorphic deities as idealized human beings. The skill of Greek sculptors reached an almost unparalleled height in the new temples on the Acropolis of Athens; but while high attainment in the visual arts indicates the presence of a high level of aesthetic consciousness, it would be hazardous to conclude that it necessarily accompanied a profound religious experience. The human form idealized was still used for portraying the gods, but only a brief step was needed to produce an art in which the human form was idealized for its own sake. The growth and decline of religions may be matched by the growth and decline of their art, and works of high artistic quality may inspire, and be inspired by, profound religious emotions; but, as the continued worship of the old wooden aniconic statue of Athena, mentioned above, indicates, it is often the antiquity of a cult object that inspires the awe that surrounds it.

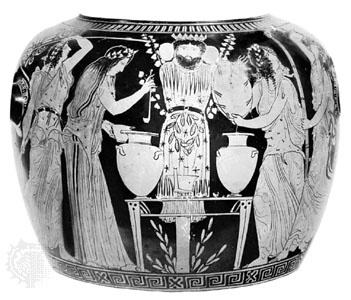

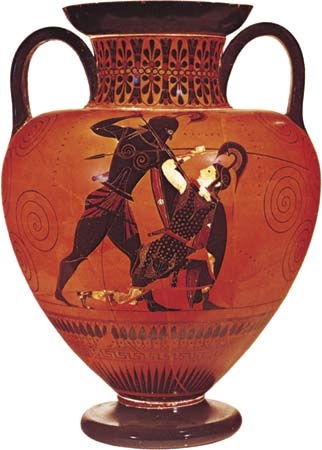

In the earliest period, terra-cotta statuettes (sculpture) of deities were small and crude, while the old cult images were made of wood and commonly attributed to Daedalus. When artists turned to bronze and marble, they depicted the anthropomorphic deities as idealized human beings. The skill of Greek sculptors reached an almost unparalleled height in the new temples on the Acropolis of Athens; but while high attainment in the visual arts indicates the presence of a high level of aesthetic consciousness, it would be hazardous to conclude that it necessarily accompanied a profound religious experience. The human form idealized was still used for portraying the gods, but only a brief step was needed to produce an art in which the human form was idealized for its own sake. The growth and decline of religions may be matched by the growth and decline of their art, and works of high artistic quality may inspire, and be inspired by, profound religious emotions; but, as the continued worship of the old wooden aniconic statue of Athena, mentioned above, indicates, it is often the antiquity of a cult object that inspires the awe that surrounds it. Apart from cult statues and dedications like the Acropolis korai (“maidens”), the gods frequently were represented on the pediments, metopes, and friezes of temples, usually in mythological scenes. For the details of ritual, vase painting has proved a fruitful source of information. Dionysiac subjects are common, though usually imaginary, but cult scenes and fertility customs also appear.

Apart from cult statues and dedications like the Acropolis korai (“maidens”), the gods frequently were represented on the pediments, metopes, and friezes of temples, usually in mythological scenes. For the details of ritual, vase painting has proved a fruitful source of information. Dionysiac subjects are common, though usually imaginary, but cult scenes and fertility customs also appear.If “Greek religion” is understood to denote the beliefs about the Greek gods and their relationships with humanity as recorded in surviving writings from the Homeric poems onward, then Greek religion was always evolving. Cultic activity, however, was conservative, as it is in most cultures. Practices continued to be observed that were no longer understood by the worshippers. High claims have been made, and continue to be made, for the quality of Greek religion as a religion, with ethical deities and strong tendencies toward monotheism. Indeed, this is probably the orthodox view. Those who contest it hold that it is incautious to extrapolate from a few scattered passages in a Greek author to produce a systematic theology that can then be used to interpret the rest of the work under discussion. The debate shows no sign of coming to an end, but the heterodox are wont to observe that Xenophanes, Pindar, and Plato evidently read Greek literature in the same way as the heterodox propose that it should be read. Plato's strictures in Books II and III of The Republic and elsewhere on Greek religion as he knew it bear eloquent testimony to this.

Additional Reading

General works include Martin P. Nilsson, Greek Popular Religion (1940, reissued as Greek Folk Religion, 1972, reprinted 1998), a sound and detailed survey, and The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion, 2nd rev. ed. (1950, reprinted 1971), the best account of origins; Jon D. Mikalson, Ancient Greek Religion (2005); W.K.C. Guthrie, The Greeks and Their Gods (1950, reprinted 2001); and Robert Parker, Athenian Religion: A History (1996).Walter Burkert, Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth (1983; originally published in German, 1972), and Greek Religion (1985; originally published in German, 1977), have broken much new ground in discussing the origins of Greek religion. Hugh Lloyd-Jones, The Justice of Zeus, 2nd ed. (1983); and Bernard Williams, Shame and Necessity (1993), bring out the value of the ethics of Greek religion. Robert Parker, Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion (1983, reissued 1996), addresses an important aspect of Greek belief.In the late 20th century scholars began paying attention to the roles of women in ancient religion. Female objects of cults are the focus of Sue Blundell and Margaret Williamson (eds.), The Sacred and the Feminine in Ancient Greece (1998). Women and the practice of religion are treated in Ross Shepard Kraemer, Women's Religions in the Greco-Roman World: A Sourcebook (2004; rev. ed. of Maenads, Martyrs, Matrons, Monastics, 1998); and Matthew Dillon, Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion (2002).Works on oracles and divination include the authoritative W.R. Halliday, Greek Divination: A Study of Its Methods and Principles (1913, reissued 1967); Hugh Bowden, Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy (2005); Robert Flacelière, Greek Oracles, 2nd ed. (1976; originally published in French, 1961); and Esther Eidinow, Oracles, Curses, and Risk Among the Ancient Greeks (2007).Mysteries and eschatology are treated in Michael B. Cosmopoulos (ed.), Greek Mysteries: The Archaeology of Ancient Greek Secret Cults (2003); Wendy Cotter, Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity: A Sourcebook (1999); W.K.C. Guthrie, Orpheus and Greek Religion: A Study of the Orphic Movement, 2nd rev. ed. (1952, reissued 1993); E.R. Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational (1951, reissued 2004), one of the best accounts; and George E. Mylonas, Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries (1961, reissued 1974), a good general survey.Works on cults and festivals include Lewis Richard Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States, 5 vol. (1896–1909, reprinted 2004), the best critical survey in English, and Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality (1921, reprinted 1970), a formal and critical account; Arthur Bernard Cook, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, 3 vol. (1914–40, vol. 1–2 reprinted in 3 vol., 1964–65), a monumental compendium of all the evidence; and Emma J. Edelstein and Ludwig Edelstein, Asclepius: A Collection and Interpretation of the Testimonies, 2 vol. (1945–46, reissued in 1 vol., 1998), the best account in English.The art and architecture of Greek religion are treated in Vincent Scully, The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods: Greek Sacred Architecture, rev. ed. (1979), a full if somewhat fanciful account of temple siting; Helmut Berve and Gottfried Gruben, Greek Temples, Theatres, and Shrines (1963), a detailed survey of the chief buildings; John Pedley, Sanctuaries and the Sacred in the Ancient Greek World (2005), a survey of places and rituals and their changes through time; and Rachel Rosenzweig, Worshipping Aphrodite: Art and Cult in Classical Athens (2004), which focuses on art and archaeology and how they shed light on social and political meaning.

- Binche

- Binchois, Gilles

- Binchy, Maeve

- binder

- binding energy

- bindweed

- Binet, Alfred

- Binford, Lewis R(oberts)

- Bing Crosby

- Bingen

- Bingham, Amelia

- Bingham, Caleb

- Bingham, George Caleb

- Bingham, Hiram

- Binghamton

- bingo

- Bing, Sir Rudolph

- Bingxin

- Bingöl

- Binkis, Kazys

- bin Laden, Osama

- Binney, Horace

- Binney, Thomas

- Binnig, Gerd

- Binnya Dala