Wright, Frank Lloyd

American architect

Introduction

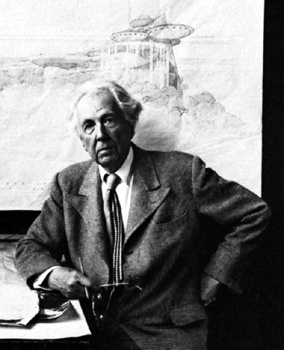

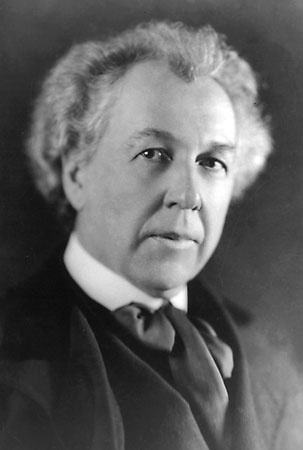

original name Frank Lincoln Wright

born June 8, 1867, Richland Center, Wisconsin, U.S.

died April 9, 1959, Phoenix, Arizona

architect and writer, the most abundantly creative genius of American architecture (Western architecture). His “Prairie style” became the basis of 20th-century residential design in the United States.

architect and writer, the most abundantly creative genius of American architecture (Western architecture). His “Prairie style” became the basis of 20th-century residential design in the United States.Early life

Wright's mother, Anna Lloyd-Jones, was a schoolteacher, aged 24, when she married a widower, William C. Wright, an itinerant 41-year-old musician and preacher. The Wrights moved with their infant son, Frank Lincoln (he would later change his middle name to Lloyd), to Iowa in 1869 and then lived successively in Rhode Island and Weymouth, Massachusetts, before eventually moving back to Wright's mother's home state of Wisconsin. The young Wright attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison for a few terms in 1885–86 as a special student, but as there was no instruction in architecture, he took engineering courses. In order to supplement the family income, Wright worked for the dean of engineering, but he did not like his situation nor the commonplace architecture around him. He dreamed of Chicago, where great buildings of unprecedented structural ingenuity were rising.

The early Chicago years

Wright left Madison early in 1887 for Chicago, where he found employment with J.L. Silsbee, doing architectural detailing. Silsbee, a magnificent sketcher, inspired Wright to achieve a mastery of ductile line and telling accent. In time Wright found more rewarding work in the important architectural firm of Dankmar Adler (Adler, Dankmar) and Louis Sullivan (Sullivan, Louis). Wright soon became chief assistant to Sullivan, and in June 1889 he married Catherine Tobin. He worked under Sullivan until 1893, at which time he opened his own architectural practice. His family grew to six children, while his firm grew until as many as 10 assistants were employed.

The first work from the new office, a house for W.H. Winslow, was sensational and skillful enough to attract the attention of the most influential architect in Chicago, Daniel Burnham (Burnham, Daniel H.), who offered to subsidize Wright for several years if Wright would study in Europe to become the principal designer in Burnham's firm. It was a solid compliment, but Wright refused, and this difficult decision strengthened his determination to search for a new and appropriate Midwestern architecture.

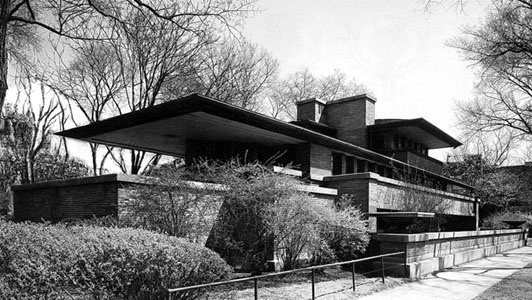

Other young architects were searching in the same way; this trend became known as the “Prairie school (Prairie style)” of architecture. By 1900 Prairie architecture was mature, and Frank Lloyd Wright, 33 years old and mainly self-taught, was its chief practitioner. The Prairie school was soon widely recognized for its radical approach to building modern homes. Utilizing mass-produced materials and equipment, mostly developed for commercial buildings, the Prairie architects discarded elaborate compartmentalization and detailing for bold, plain walls, roomy family living areas, and perimeter heating below broad glazed areas. Comfort, convenience, and spaciousness were economically achieved. Wright alone built about 50 Prairie houses from 1900 to 1910. The typical Wright-designed residence from this period displayed a wide, low roof over continuous window bands that turned corners, defying the conventional boxlike structure of most houses, and the house's main rooms flowed together in an uninterrupted space.

Other young architects were searching in the same way; this trend became known as the “Prairie school (Prairie style)” of architecture. By 1900 Prairie architecture was mature, and Frank Lloyd Wright, 33 years old and mainly self-taught, was its chief practitioner. The Prairie school was soon widely recognized for its radical approach to building modern homes. Utilizing mass-produced materials and equipment, mostly developed for commercial buildings, the Prairie architects discarded elaborate compartmentalization and detailing for bold, plain walls, roomy family living areas, and perimeter heating below broad glazed areas. Comfort, convenience, and spaciousness were economically achieved. Wright alone built about 50 Prairie houses from 1900 to 1910. The typical Wright-designed residence from this period displayed a wide, low roof over continuous window bands that turned corners, defying the conventional boxlike structure of most houses, and the house's main rooms flowed together in an uninterrupted space.During this period Wright lectured repeatedly; his most famous talk, The Art and Craft of the Machine, was first printed in 1901. His works were featured in local exhibitions from 1894 through 1902. In that year he built the home of the W.W. Willitses, the first masterwork of the Prairie school. In 1905 he traveled to Japan.

By now Wright's practice encompassed apartment houses, group dwellings, and recreation centres. Most remarkable were his works for business and church. The administrative block for the Larkin Company, a mail-order firm in Buffalo, New York, was erected in 1904 (demolished in 1950). Abutting the railways, it was sealed and fireproof, with filtered, conditioned, mechanical ventilation; metal desks, chairs, and files; ample sound-absorbent surfaces; and excellently balanced light, both natural and artificial. Two years later the Unitarian church of Oak Park, Illinois, Unity Temple, was under way; in 1971 it was registered as a national historic landmark. Built on a minimal budget, the small house of worship and attached social centre achieved timeless monumentality. The congregation still meets in the building's intimate, top-lit cube of space, which is turned inward, away from city noises. The Unity Temple improved on the Larkin Building in the consistency of its structure (it was built of concrete, with massive walls and reinforced roof) and in the ingenious interior ornament that emphasized space while subordinating mass. Unlike many contemporary architects, Wright took advantage of ornament to define scale and accentuation.

Europe and Japan

By 1909 Wright's estrangement from his wife and his relationship with Mamah Cheney, the wife of one of his former clients, were damaging his ability to obtain architectural commissions. In that year Wright began work on his own house near Spring Green, Wisconsin, which he named Taliesin, before he left for Europe that September. Abroad, Wright set to work on two books, both first published in Germany, which became famous; a grand double portfolio of his drawings (Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe, 1910) and a smaller but full photographic record of his buildings (Ausgeführte Bauten, 1911). With a draftsman, Taylor Willey, and his eldest son, Lloyd Wright, the architect produced the numerous beautiful drawings published in these portfolios by reworking renderings brought from Chicago, Oak Park, and Wisconsin.

By 1911 Wright and Cheney, still unmarried since Wright could not get a divorce, were living at Taliesin (Taliesin and Taliesin West). Wright's career suffered from unfavourable publicity generated by his relationship with Cheney, but he found a few loyal clients like the Avery Coonleys, whose suburban estate, west of Chicago, the grand masterwork of the Prairie style, he had designed in 1908. In 1912 Wright designed his first skyscraper, a slender concrete slab, prophetic but unbuilt.

At this time the Japanese began to consider Wright as architect for a new Tokyo hotel where visitors could be officially entertained and housed in Western style. Thus, early in 1913 he and Cheney spent some months in Japan. The following year Wright was occupied in Chicago with the rushed construction of Midway Gardens, a complex planned to include open-air dining, other restaurants, and clubs. Symmetrical in plan, this building was sparklingly decorated with abstract and near-abstract art and ornament. Its initial success was cut short by Prohibition, however, and it was later demolished. Just before Midway Gardens opened, Wright was dealt a crushing blow; Cheney and her children, who were visiting her at Taliesin, and four others were killed by an insane houseman, and the living quarters of the house were devastated by fire.

Stunned by the tragedy, Wright began to rebuild his home and was soon joined by the sculptor Miriam Noel, who became his mistress. In 1916 they went to Japan, which was to be their home for five years.

The Imperial Hotel (1915–22, dismantled 1967) in Tokyo was one of Wright's most significant works in its lavish comfort, splendid spaces, and unprecedented construction. Because of its revolutionary, floating cantilever construction, it was one of the only large buildings that safely withstood the devastating earthquake that struck Tokyo in 1923. No one still doubted Wright's complete mastery of his art, but he continued to experience difficulty in acquiring major commissions because of his egocentric and unconventional behaviour and the scandals that surrounded his private life.

The '20s and '30s

Wright's transpacific journeys took him to California, where he met a wealthy, demanding client, Aline Barnsdall, who about 1920 built to Wright's designs a complex of houses and studios amid gardens on an estate called Olive Hill; these now serve as the Municipal Art Gallery in Hollywood. In 1923 and 1924 Wright built four houses in California, using textured concrete blocks with a fresh sense of form.

Late in 1922 Wright's wife Catherine divorced him at last. His relationship with Miriam Noel ended, and in 1925 Taliesin again burned, struck by lightning, and again Wright rebuilt it. That same year a Dutch publication, Wendingen, presented Wright's newer work fully and handsomely, with praise from Europeans. In 1924 Wright had met Olgivanna Hinzenberg; soon she came to live with Wright permanently, and they married in 1928. Meanwhile, Wright's finances had fallen into a catastrophic state; in 1926–27 he sold a great collection of Japanese prints but could not rescue Taliesin from the bank that seized it. Amid these debacles, Wright began to write An Autobiography, as well as a series of articles on architecture, which appeared in 1927 and 1928. Finally, some of Wright's admirers set up Wright, Incorporated—a firm that owned his talents, his properties, and his debts—that effectively shielded him. In 1929 Wright designed a tower of studios cantilevered from a concrete core, to be built in New York City; in various permutations it appeared as one of his best concepts. (In 1956 the St. Mark's Tower project was finally realized as the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.)

Late in 1922 Wright's wife Catherine divorced him at last. His relationship with Miriam Noel ended, and in 1925 Taliesin again burned, struck by lightning, and again Wright rebuilt it. That same year a Dutch publication, Wendingen, presented Wright's newer work fully and handsomely, with praise from Europeans. In 1924 Wright had met Olgivanna Hinzenberg; soon she came to live with Wright permanently, and they married in 1928. Meanwhile, Wright's finances had fallen into a catastrophic state; in 1926–27 he sold a great collection of Japanese prints but could not rescue Taliesin from the bank that seized it. Amid these debacles, Wright began to write An Autobiography, as well as a series of articles on architecture, which appeared in 1927 and 1928. Finally, some of Wright's admirers set up Wright, Incorporated—a firm that owned his talents, his properties, and his debts—that effectively shielded him. In 1929 Wright designed a tower of studios cantilevered from a concrete core, to be built in New York City; in various permutations it appeared as one of his best concepts. (In 1956 the St. Mark's Tower project was finally realized as the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.)The stock market crash of 1929 ended all architectural activity in the United States, and Wright spent the next years lecturing at Chicago, New York City, and Princeton, New Jersey. Meanwhile an exhibition of his architecture toured Europe and the United States. In 1932 An Autobiography and the first of Wright's books on urban problems, The Disappearing City, were published. In the same year the Wrights opened the Taliesin Fellowship, a training program for architects and related artists who lived in and operated Taliesin, its buildings, and further school structures as they built or remodeled them. From 20 to 60 apprentices worked with Wright each year; a few remained for decades, constituting his main office staff. In the winter Wright and his entourage packed up and drove to Arizona, where Taliesin West was soon to be built. At this time Wright developed an effective system for constructing low-cost homes and, over the years, many were built. Unlike the Prairie houses these “Usonians” were flat roofed, usually of one floor placed on a heated concrete foundation mat; among them were some of Wright's best works—e.g., the Jacobs house (1937) in Westmorland, Wisconsin, near Madison, and the Winckler-Goetsch house (1939) at Okemos, Michigan.

International success and acclaim

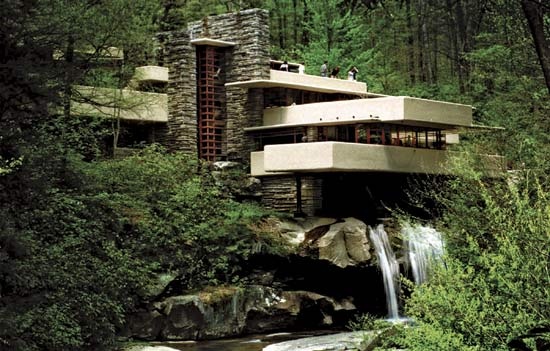

Wright gradually reemerged as a leading architect; when the national economy improved, two commissions came to him that he utilized magnificently. The first was for a weekend retreat near Pittsburgh in the Allegheny Mountains. This residence, Fallingwater, was cantilevered over a waterfall with a simple daring that evoked wide publicity from 1936 to the present. Probably Wright's most-admired work, it was later given to the state and was opened to visitors. The second important commission was the administrative centre for S.C. Johnson, wax manufacturers, at Racine, Wisconsin. Here Wright combined a closed, top-lit space with recurving forms and novel, tubular mushroom columns. The resulting airy enclosure is one of the most humane workrooms in modern architecture. Each of these buildings showed Wright to be as innovative as younger designers and a master of unique expressive forms.

Wright gradually reemerged as a leading architect; when the national economy improved, two commissions came to him that he utilized magnificently. The first was for a weekend retreat near Pittsburgh in the Allegheny Mountains. This residence, Fallingwater, was cantilevered over a waterfall with a simple daring that evoked wide publicity from 1936 to the present. Probably Wright's most-admired work, it was later given to the state and was opened to visitors. The second important commission was the administrative centre for S.C. Johnson, wax manufacturers, at Racine, Wisconsin. Here Wright combined a closed, top-lit space with recurving forms and novel, tubular mushroom columns. The resulting airy enclosure is one of the most humane workrooms in modern architecture. Each of these buildings showed Wright to be as innovative as younger designers and a master of unique expressive forms.

Thereafter commissions flowed to Wright for every kind of building and from many parts of the world. His designs for the campus and buildings of Florida Southern College at Lakeland (1940–49) were begun, and the V.C. Morris Shop (1948) in San Francisco was executed. Among Wright's many late designs, executed and unexecuted, two major works stand out: the Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Marin County government centre near San Francisco. The Guggenheim Museum was commissioned as early as 1943 to house a permanent collection of abstract art. Construction began in 1956, and the museum opened in 1959 after Wright's death. The Guggenheim, which has no separate floor levels but instead uses a spiral ramp, realized Wright's ideal of a continuous space and is one of his most significant buildings. The Marin County complex is Wright's only executed work for government, and the only one that integrates architecture, highway, and automobile, a concept that had long preoccupied Wright.

Thereafter commissions flowed to Wright for every kind of building and from many parts of the world. His designs for the campus and buildings of Florida Southern College at Lakeland (1940–49) were begun, and the V.C. Morris Shop (1948) in San Francisco was executed. Among Wright's many late designs, executed and unexecuted, two major works stand out: the Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Marin County government centre near San Francisco. The Guggenheim Museum was commissioned as early as 1943 to house a permanent collection of abstract art. Construction began in 1956, and the museum opened in 1959 after Wright's death. The Guggenheim, which has no separate floor levels but instead uses a spiral ramp, realized Wright's ideal of a continuous space and is one of his most significant buildings. The Marin County complex is Wright's only executed work for government, and the only one that integrates architecture, highway, and automobile, a concept that had long preoccupied Wright.A prolific author, Wright produced An Autobiography (published 1932, revised 1943), An Organic Architecture (1939), An American Architecture (1955), and A Testament (1957).

Wright was a great originator and a highly productive architect. He designed some 800 buildings, of which 380 were actually built and about 280 are still standing. Throughout his career he retained the use of ornamental detail, earthy colours, and rich textural effects. His sensitive use of materials helped to control and perfect his dynamic expression of space, which opened a new era in American architecture. He became famous as the creator and expounder of “organic architecture,” his phrase indicating buildings that harmonize both with their inhabitants and with their environment. The boldness and fertility of his invention and his command of space are probably his greatest achievements.

Additional Reading

Among thousands of books on Wright are a number of picture books and a number of works on specific buildings and styles. Robert L. Sweeney, Frank Lloyd Wright: An Annotated Bibliography (1978); and Donald Langmead, Frank Lloyd Wright: A Bio-Bibliography (2003), contain information on thousands of books, periodical articles, reviews, catalogs, and other items by and about Wright. Reliable biographies include Robert C. Twombly, Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture (1979); Brendan Gill, Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright (1987, reissued 1998); Meryle Secrest, Frank Lloyd Wright (1992, reissued 1998); Kathryn Smith, Frank Lloyd Wright: America's Master Architect (1998); and Ada Louise Huxtable, Frank Lloyd Wright (2004). A classic study of Wright's work is Henry Russell Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, 1887–1941: The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright (1942, reprinted 1975). Other useful books on Wright's work include Grant Hildebrand, The Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright's Houses (1991); David Larkin and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer (eds.), Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks (1993); Neil Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright (1996); and Gail Satier, Frank Lloyd Wright's Living Space: Architecture's Fourth Dimension (1999). Vincent Scully, Frank Lloyd Wright (1960); Arthur Drexler, The Drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright (1962); Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life, His Work, His Words (1966), containing a full but occasionally inaccurate listing of Wright's buildings after 1941; Thomas A. Heinz, Frank Lloyd Wright (1982, reissued 1992); Patrick J. Meehan (ed.), The Master Architect: Conversations with Frank Lloyd Wright (1984); Carol R. Bolon, Robert S. Nelson, and Linda Seidel (eds.), The Nature of Frank Lloyd Wright (1988); Terence Riley and Peter Reed (eds.), Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect (1994); Arlene Sanderson (ed.), Wright Sites: A Guide to Frank Lloyd Wright Public Places, rev. 2nd ed. (1995); Robert McCarter, Frank Lloyd Wright (1997); and William Allin Storrer, The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion (1993), and The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog (2001), are also valuable studies.

- Thomas Holloway

- Thomas Hood

- Thomas Hooker

- Thomas Hope

- Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet

- Thomas Hudson

- Thomas Hughes

- Thomas Hunt Morgan

- Thomas Hutchinson

- Thomas H. Weller

- Thomas, II Chippendale

- Thomas II de Beauchamp, 4th Earl of Warwick

- Thomas II de Beauchamp Warwick, 4th Earl of

- Thomas, Isaiah

- Thomas, Isiah

- Thomasius, Christian

- Thomas Jackson Rodman

- Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson

- Thomas Jan Stieltjes

- Thomas Jefferson

- Thomas Jefferson: A Firebell in the Night

- Thomas Jefferson: An American Education for American Youth

- Thomas Jefferson: A Simple and Inexpensive Government

- Thomas Jefferson: Debate on Independence

- Thomas Jefferson: First Inaugural Address