Yukon River

river, North America

Introduction

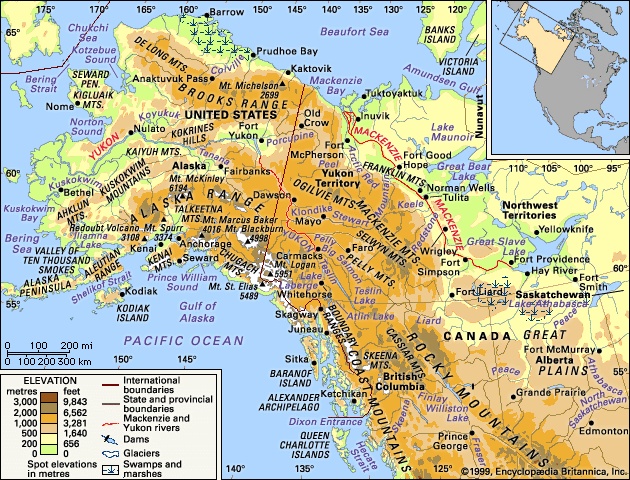

major North American river that flows through the central Yukon territory of Canada and central Alaska. It measures 1,980 miles (3,190 kilometres) from the headwaters of the McNeil River (a tributary of the Nisutlin River). The Yukon discharges into the Bering Sea after flowing northwestward and then generally southwestward through a low plateau that slopes down across Alaska. The main east- and north-bank tributaries are the Teslin, Big Salmon, Pelly, Stewart, Klondike, Porcupine, and Koyukuk; the west- and south-bank tributaries are the Takhini, White, and Tanana. Its headwater tributaries drain an area of about 328,000 square miles (850,000 square kilometres) out of a surrounding semicircle of high mountains. This huge area—larger than Turkey—was occupied solely by North American Indians until the mid-19th century, when peoples of European descent (including explorers from the eastward-expanding Russian Empire) began to move into the region, first as fur traders and then in search of mineral wealth. The discovery of gold on the Klondike (Klondike River) in 1896 precipitated an influx of settlement that created an international mythology of romantic frontier existence associated with the name Yukon.

major North American river that flows through the central Yukon territory of Canada and central Alaska. It measures 1,980 miles (3,190 kilometres) from the headwaters of the McNeil River (a tributary of the Nisutlin River). The Yukon discharges into the Bering Sea after flowing northwestward and then generally southwestward through a low plateau that slopes down across Alaska. The main east- and north-bank tributaries are the Teslin, Big Salmon, Pelly, Stewart, Klondike, Porcupine, and Koyukuk; the west- and south-bank tributaries are the Takhini, White, and Tanana. Its headwater tributaries drain an area of about 328,000 square miles (850,000 square kilometres) out of a surrounding semicircle of high mountains. This huge area—larger than Turkey—was occupied solely by North American Indians until the mid-19th century, when peoples of European descent (including explorers from the eastward-expanding Russian Empire) began to move into the region, first as fur traders and then in search of mineral wealth. The discovery of gold on the Klondike (Klondike River) in 1896 precipitated an influx of settlement that created an international mythology of romantic frontier existence associated with the name Yukon.Physical features

Physiography and hydrology

The McNeil headwaters rise in the Pelly Mountains of south-central Yukon territory and flow south into Teslin Lake and thence into the Teslin River. The main headwaters of the Yukon River, however, flow from Atlin Lake and Tagish Lake in the vicinity of the border between British Columbia and the Yukon territory. About 50 miles downstream the Yukon once rushed through the rocky walls of narrow Miles Canyon and tumbled over rock ledges at Whitehorse Rapids. These obstacles to river travel during the gold rush era necessitated the construction of the short railroad from Skagway, Alaska, to Whitehorse in the Yukon territory, the latter becoming the southern terminal of water transport northward. The river has since been dammed south of Whitehorse for hydroelectric power; the rapids are buried under the reservoir lake, and deep water fills the former canyon.

The McNeil headwaters rise in the Pelly Mountains of south-central Yukon territory and flow south into Teslin Lake and thence into the Teslin River. The main headwaters of the Yukon River, however, flow from Atlin Lake and Tagish Lake in the vicinity of the border between British Columbia and the Yukon territory. About 50 miles downstream the Yukon once rushed through the rocky walls of narrow Miles Canyon and tumbled over rock ledges at Whitehorse Rapids. These obstacles to river travel during the gold rush era necessitated the construction of the short railroad from Skagway, Alaska, to Whitehorse in the Yukon territory, the latter becoming the southern terminal of water transport northward. The river has since been dammed south of Whitehorse for hydroelectric power; the rapids are buried under the reservoir lake, and deep water fills the former canyon.River ice begins to break up at Whitehorse, the territorial capital, in early May and loosens northward on Lake Laberge a few days later. The snow-fed tributaries from the Mackenzie Mountains to the east reach their flood peak in June, but glacier-fed streams such as the White, draining the north slopes of the St. Elias Mountains, do not have their greatest runoff until July. Once these peak runoff flows have passed, the Yukon River becomes a shallow, braided stream, as summer precipitation in the Yukon basin is low—about 6 inches (150 millimetres) of summer rainfall is recorded at Whitehorse and Dawson.

North of Lake Laberge, the Yukon flows through a broad, generally flat-bottomed valley; riverbanks are not high, and the river meanders lazily across the valley floor, with numerous sandbars and small islands dotting the channel. About 25 miles north of the village of Carmacks, four small, rocky islands split the river into the Five Finger Rapid area, and the current flows swiftly past these islands. At the village of Selkirk, the junction of the Pelly River swells the Yukon's volume considerably, for the Pelly drains about 19,700 square miles of the generally uninhabited western slopes of the Mackenzie Mountains. North of Selkirk, the Yukon is a clear and gentle river, with numerous low islands breaking the channel. The White River, with a drainage area of about 19,500 square miles, adds silt from the glaciers and mountains to the southwest. The Stewart River, having about the same drainage area as the White River, flows out of the mining area of Mayo-Keno City to the east. At Dawson the Yukon has an average flow of 74,000 cubic feet (2,095 cubic metres) per second, but there is a wide difference between the high-water flows of June and the low water beneath the ice in March. There are no hydroelectric power developments on the Yukon, except for a small plant at Whitehorse. The river is thought to have considerable generating potential; but, because there has been no demand for power, no accurate evaluations have been made.

The Klondike is a small, east-bank tributary that joins the Yukon at the historic territorial town of Dawson. The Klondike valley floor is covered with sinuous, wormlike ridges of gravel deposited behind the gold dredges that have worked their way through the valley gravels over a period of nearly a century.

Downstream from Dawson the river valley narrows, and the low plateau is broken by mountains that rise to elevations of more than 4,000 feet, about 15 miles north of the Yukon River. The river itself is about 1,000 feet above sea level before it crosses the border into Alaska. The next large tributary, the Porcupine River, joins the Yukon at Fort Yukon, Alaska; the Porcupine drains the northern Yukon territory and the southeastern slope of the high and rugged Brooks Range in Alaska, a land occupied by a small population of Indians. The Yukon then flows generally westward for about 150 miles across a broad, flat valley; the many channels of the braided river thread their way through numerous islands and sandbars. At the western end of the “flats” is a narrow gorge, where the river rushes through a low mountain barrier known as the ramparts.

At the junction of the Tanana River, the main southern tributary in Alaska, the Yukon is less than 300 feet above sea level. Upstream on the Tanana lies Fairbanks, the largest city in the Yukon River basin. The snow- and glacier-fed waters of the Tanana drain the north slopes of the high Alaska Range, but, after the peak runoff in July, the Tanana becomes a shallow stream by late summer. West of the Yukon's confluence with the Tanana, the Yukon valley broadens south of the river; but within 5 miles of its northern banks rise the low Kokrines Hills, with peaks over 3,000 feet in altitude. About 175 miles downstream from the Tanana confluence, the last major tributary, the Koyukuk, drains southward from the south-central slopes of the Brooks Range. The Yukon there is only 117 feet above sea level and only about 100 miles due east of Norton Sound, but the river is forced to detour several hundred miles to the south and west around mountainous terrain.

As the Yukon nears the Bering Sea, it bends sharply northward to empty into Norton Sound. The river delta is about 40 miles across, swampy, and lake-covered. Many of the distributary channels are shallow, but the northeastern one, Apoon Pass, was once used by riverboats.

Climate

The valleys of the Yukon River basin, where nearly all of the population lives, have a subarctic climate with relatively warm, short summers; but the treeless upper mountain slopes, where there are no weather stations, are classified as having an Arctic climate. Bitterly cold air masses from Siberia or the Arctic Ocean cross Alaska and the Yukon territory throughout the long, dark winter, but occasional warm air masses from the Pacific Ocean can penetrate over the high barrier of the St. Elias Mountains and bring warmer winter temperatures to the Whitehorse area. January mean temperatures are about -24° F (-31° C) at Dawson and about -6° F (-21° C) at Whitehorse. In 1947 the lowest temperature officially recorded in North America, -81° F (-63° C), was reported at Snag along the Alaska Highway in southwestern Yukon.

Average summer temperatures in the valleys of this high-latitude region, with its long hours of summer daylight, are moderately warm, with July mean temperatures of about 60° F (16° C) at Dawson and slightly lower at Whitehorse. Annual precipitation is low, as it is in most of northwestern Canada and central Alaska, with an average of about 10 inches (260 millimetres) recorded at Whitehorse and 12 inches at Dawson. Almost 50 percent of the precipitation falls as rain during the four summer months.

Plant and animal life

Coniferous forests grow to low height and low densities across the valley floors and lower mountain slopes of the Yukon River basin. The upper tree line is at an elevation of about 3,500 to 4,500 feet, depending on local exposure and drainage; thus, about two-thirds of the mountainous Yukon territory is treeless. The largest stands of potentially commercial forest are along the Alaska Highway in the Liard River valley in the southeastern Yukon, but this area is far from markets. White spruce is dominant on the valley floors, and black spruce grows in the poorly drained areas. Outbreaks of spruce budworm threaten large areas of these forests. In addition, Alpine fir and lodgepole pine are found in the lower areas along the Alaska Highway across the southern Yukon.

A varied animal life inhabits the forested valleys. The larger mammals include black, brown, and grizzly bears; caribou, deer, and moose; and mountain goats and sheep at higher elevations. Timber wolves are common. Game birds such as grouse and ptarmigan are found, and waterfowl include many species of geese, swans, and ducks. The usual furbearers trapped by the Indian population include muskrat, mink, marten, lynx, weasel, fox, fisher, and squirrel. In the river itself are found species of such fish as Arctic grayling, burbot, pike, salmon, and whitefish.

The people and economy

The Yukon River basin has remained sparsely populated in the century and a half since it was first settled by Europeans. The lure of mineral wealth has been the main attraction of the region, and mining has maintained several of the settlements. Gold brought people to Fairbanks and Dawson; when the gold was depleted, Fairbanks continued to grow as it took on administrative and transportation functions for east-central Alaska, but the population of Dawson declined to only a tiny fraction of its size in the heyday of the gold rush. In the 1950s the Yukon territorial capital was moved from Dawson to the more accessible city of Whitehorse, on the Alaska Highway. Whitehorse then developed transportation and service functions for the other small settlements in the southern Yukon region and became the largest city in the territory.

Mines are marginal economic operations in the Yukon River basin because the area is far from world markets and has only a few land-transport routes. Lead, zinc, and silver have been produced at Keno City, near Mayo, since the 1920s, but the high-grade ore has to be transported southward to Trail, B.C., near the U.S.-Canadian border, for smelting. Since the early 1970s, copper and base metals have been mined at Faro, on the Pelly River west of the Mackenzie Mountains, and ore concentrates have been transported by truck to Whitehorse. Some gold is still extracted intermittently from alluvial deposits in several Yukon tributaries, and deposits of tungsten, iron, and coal are known.

Other economic activities are of minor importance in the Yukon basin. Fur trapping has been the traditional livelihood for the region's Indians, but low monetary returns plus the attraction of better pay from wage labour in the towns have taken many Indians away from their former migratory lives. Agriculture is a minor activity. Although vegetables, pasturage, and coarse grains can be grown during the long days of the short summer, only a small number of operating farms exist; most of the food consumed in Whitehorse, for example, is shipped in from southern Canadian farms. Perhaps the main resource of the Yukon basin is its scenery, isolation, and sparse population, all of which are attractive to tourists seeking to escape the more crowded and less scenically endowed areas of the continent. The many vistas of the winding river, its forested slopes supporting game and wildlife, and the game fish in the tributary lakes are all part of an attractive natural environment that has become more difficult to find in southern regions.

History

The delta mouth of the Yukon River was known to the Russians when they occupied nearby St. Michael Island in 1831, but the headwaters in British North America remained unknown for another decade. By 1838 Russian fur traders had explored the river as far inland as Nulato (Alaska), where they established a post near the junction of Koyukuk River. By 1846 the Russians had mapped almost 600 miles of the lower river. The trader Robert Campbell, of the Hudson's Bay Company, explored Pelly River, one of the Yukon headwaters, in 1840. In 1848 he established a trading post at Fort Selkirk, at the junction of the Pelly and Yukon rivers, in order to trade with the local Indians. In 1851 Campbell explored the Yukon downstream to the junction of the Porcupine River, where Fort Yukon had been built in 1847. When the trading post at Fort Selkirk was burned by hostile Indians in 1852, however, Europeans withdrew from the upper Yukon basin for two decades.

Water transportation gradually extended upstream from the mouth of the Bering Sea. Shallow-draft steamers had been operating on the river in Alaska after 1866, and the first riverboat reached the Yukon territory a few years later. The Yukon River became known to the world following the rich gold (gold rush) strikes in 1896 on the Klondike River in Canada. In the summer of 1898 at least 20 vessels rounded the extremity of southwestern Alaska and navigated the lower Yukon River to reach the booming community of Dawson City (the name later was shortened to Dawson). Other gold seekers took a shorter route by penetrating north through the Coast Mountains from Skagway, Alaska; they made crude boats or rafts on Bennett Lake and floated downstream to the rapids near Whitehorse. From there riverboats took passengers and freight downstream to Dawson. When gold-mining activity declined during the years following World War I, the use of water transport on the Yukon River also decreased. The riverboats ceased to operate on the Canadian part of the river in the 1950s, being replaced by road and air transport to Dawson and other small towns.

Water transportation gradually extended upstream from the mouth of the Bering Sea. Shallow-draft steamers had been operating on the river in Alaska after 1866, and the first riverboat reached the Yukon territory a few years later. The Yukon River became known to the world following the rich gold (gold rush) strikes in 1896 on the Klondike River in Canada. In the summer of 1898 at least 20 vessels rounded the extremity of southwestern Alaska and navigated the lower Yukon River to reach the booming community of Dawson City (the name later was shortened to Dawson). Other gold seekers took a shorter route by penetrating north through the Coast Mountains from Skagway, Alaska; they made crude boats or rafts on Bennett Lake and floated downstream to the rapids near Whitehorse. From there riverboats took passengers and freight downstream to Dawson. When gold-mining activity declined during the years following World War I, the use of water transport on the Yukon River also decreased. The riverboats ceased to operate on the Canadian part of the river in the 1950s, being replaced by road and air transport to Dawson and other small towns.Additional Reading

Richard K. Mathews, The Yukon (1968), is an informative geography from the series Rivers of America. A brief study of hydrology is found in United States, Army, Corps of Engineers, Alaska District, Yukon and Kuskokwim River Basins, Alaska (1987). Yukon Data Book (biennial) is a reference periodical published by the Yukon Territory government. Informative illustrated descriptions of travel along the river include Keith Tryck, Yukon Passage: Rafting 2000 Miles to the Bering Sea (1980); and Stan Cohen, Yukon River Steamboats (1982). Allen A. Wright, Prelude to Bonanza (1976), describes the discovery and exploration of the territory. Other histories of the territory and the people include R.C. Coutts, Yukon: Places & Names (1980); Melody Webb, The Last Frontier (1985, reissued as Yukon: The Last Frontier, 1993); and Catharine McClellan, Part of the Land, Part of the Water: A History of the Yukon Indians (1987). Surveys of present-day conditions can be found in D.K. Redpath, Land Use Programs in Canada, Yukon Territory (1979).

- Sir Vincent Wigglesworth

- Sir Vivian Ernest Fuchs

- Sir Viv Richards

- Sir V.S. Naipaul

- Sir Wallace Edward Rowling

- Sir Wallis Budge

- Sir Walter, 1st Baronet Scott

- Sir Walter Besant

- Sir Walter Nash

- Sir Walter Parratt

- Sir Walter Raleigh

- Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet

- Sir Wilfred Grenfell

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier

- Sir William, 1st Baronet Bowman

- Sir William, 1st Baronet Fairbairn

- Sir William, 1st Baronet Jenner

- Sir William, 1st Baronet Johnson

- Sir William, 2nd Baronet Congreve

- Sir William, 3rd Baronet Wyndham

- Sir William, 9th Baronet Hamilton

- Sir William Abbott Herdman

- Sir William Alexander Craigie

- Sir William, Baronet Osler

- Sir William, Baronet Pepperrell