horse

mammal

Introduction

a hoofed, herbivorous mammal of the family Equidae. It comprises a single species, Equus caballus, whose numerous varieties are called breeds. Before the advent of mechanized vehicles, the horse was widely used as a draft animal and riding on horseback was one of the chief means of transportation.

a hoofed, herbivorous mammal of the family Equidae. It comprises a single species, Equus caballus, whose numerous varieties are called breeds. Before the advent of mechanized vehicles, the horse was widely used as a draft animal and riding on horseback was one of the chief means of transportation.General features

In prehistoric times the wild horse was probably first hunted for food. When its domestication took place is unknown, but it certainly was long after the domestication of the dog or of cattle. It is supposed that the horse was first used by a tribe of Indo-European origin that lived in the steppes north of the chain of mountains adjacent to the Black and Caspian seas. Influenced by climate, food, and humans, the horse rapidly acquired its present form.

In prehistoric times the wild horse was probably first hunted for food. When its domestication took place is unknown, but it certainly was long after the domestication of the dog or of cattle. It is supposed that the horse was first used by a tribe of Indo-European origin that lived in the steppes north of the chain of mountains adjacent to the Black and Caspian seas. Influenced by climate, food, and humans, the horse rapidly acquired its present form. The relationship of the horse to humans has been unique. The horse is a partner and friend. It plowed fields and brought in the harvest, hauled goods and conveyed passengers, followed game and tracked cattle, and carried combatants into battle and adventurers to unknown lands. It has provided recreation in the form of jousts, tournaments, carousels, and the sport of riding. The influence of the horse is expressed in the English language in such terms as chivalry and cavalier, which connote honour, respect, good manners, and straightforwardness.

The relationship of the horse to humans has been unique. The horse is a partner and friend. It plowed fields and brought in the harvest, hauled goods and conveyed passengers, followed game and tracked cattle, and carried combatants into battle and adventurers to unknown lands. It has provided recreation in the form of jousts, tournaments, carousels, and the sport of riding. The influence of the horse is expressed in the English language in such terms as chivalry and cavalier, which connote honour, respect, good manners, and straightforwardness.The horse is the “proudest conquest of Man,” according to the French zoologist Le Comte de Buffon. Its place was at its master's side in the graves of the Scythian kings or in the tombs of the pharaohs. Many early human cultures were centred on possession of the horse. Superstition read meaning into the colours of the horse, and a horse's head suspended near a grave or sanctuary or on the gables of a house conferred supernatural powers on the place. Greek mythology created the centaur, the most obvious symbol of the oneness of horse and rider. White stallions were the supreme sacrifice to the gods, and the Greek general Xenophon recorded that “Gods and heroes are depicted on well-trained horses.” A beautiful and well-trained horse was, therefore, a status symbol in ancient Greece. Kings, generals, and statesmen, of necessity, had to be horsemen. The names of famous horses are inseparably linked to those of their famous riders: Bucephalus, the charger of Alexander the Great; Incitatus, once believed to have been made a senator by the Roman emperor Caligula (see Researcher's Note); El Morzillo, Cortés's favourite horse, to whom the Indians erected a statue; Roan Barbery, the stallion of Richard II, mentioned by Shakespeare; Copenhagen, the Duke of Wellington's horse, which was buried with military honours.

The horse has occupied a special place in the realm of art. From the Stone Age drawings to the marvel of the Parthenon frieze, from Chinese Tang dynasty tomb sculptures to Leonardo da Vinci's sketches and Verrocchio's Colleoni, from the Qurʿān to modern literature, the horse has inspired artists of all ages and in all parts of the world.

The horse has occupied a special place in the realm of art. From the Stone Age drawings to the marvel of the Parthenon frieze, from Chinese Tang dynasty tomb sculptures to Leonardo da Vinci's sketches and Verrocchio's Colleoni, from the Qurʿān to modern literature, the horse has inspired artists of all ages and in all parts of the world.The horse in life has served its master in travels, wars, and labours and in death has provided many commodities. Long before their domestication horses were hunted by primitive tribes for their flesh, and horsemeat is still consumed by people in parts of Europe and in Iceland and is the basis of many pet foods. Horse bones and cartilage are used to make glue. Tetanus antitoxin is obtained from the blood serum of horses previously inoculated with tetanus toxoid. From horsehide a number of articles are manufactured, including fine shoes and belts. The cordovan leather fabricated by the Moors in Córdoba, Spain, was originally made from horsehide. Stylish fur coats are made of the sleek coats of foals. Horsehair has wide use in upholstery, mattresses, and stiff lining for coats and suits; high-quality horsehair, usually white, is employed for violin bows. Horse manure, which today provides the basis for cultivation of mushrooms, was used by the Scythians for fuel. Mare's milk was drunk by the Scythians, the Mongols, and the Arabs.

Form and function

A mature male horse is called a stallion, the female a mare. A stallion used for breeding is known as a stud. A castrated stallion is commonly called a gelding. Formerly, stallions were employed as riding horses, while mares were kept for breeding purposes only. Geldings were used for work and as ladies' riding horses. Recently, however, geldings generally have replaced stallions as riding horses. Young horses are known as foals; male foals are called colts and females fillies.

A mature male horse is called a stallion, the female a mare. A stallion used for breeding is known as a stud. A castrated stallion is commonly called a gelding. Formerly, stallions were employed as riding horses, while mares were kept for breeding purposes only. Geldings were used for work and as ladies' riding horses. Recently, however, geldings generally have replaced stallions as riding horses. Young horses are known as foals; male foals are called colts and females fillies.Anatomical adaptations

The primitive horse probably stood 12 hands (about 120 cm, or 48 inches) tall at the withers, the high point on the back at the base of the neck, and was dun coloured. Domestic horses gone wild, such as the mustangs of western North America, tend to revert to those primitive features under random mating; they generally are somewhat taller (about 15 hands), usually gray, dun, or brownish in colour, and move in herds led by a stallion.

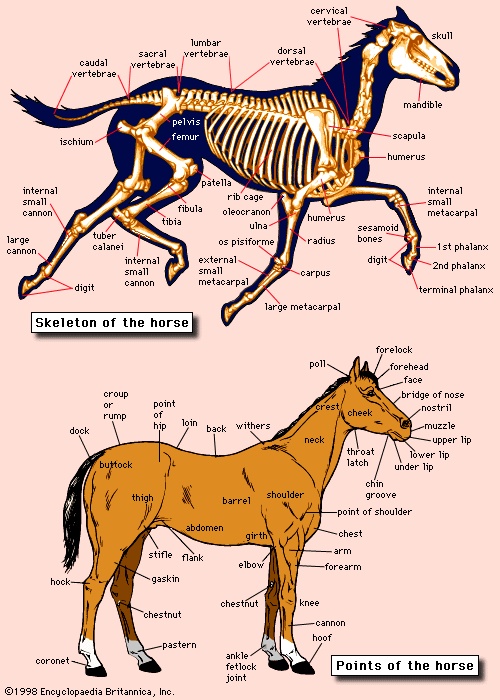

The horse's general form is characteristic of an animal of speed: the long leg bones (skeleton) pivot on pulley-like joints that restrict movement to the fore and aft, the limbs are levered to muscle masses in such a way as to provide the most efficient use of energy, and the compact body is supported permanently on the tips of the toes, allowing fuller extension of the limbs in running.

The rounded skull houses a large and complex brain, well developed in those areas that direct muscle coordination. While the horse is intelligent among subhuman animals, it is safe to say that the horse is more concerned with the functioning of its acute sensory reception and its musculature than with mental processes. Though much has been written about “educated” horses that appear to exhibit an ability to spell and count, it is generally agreed that in such cases a very perceptive animal is responding to cues from its master. But this ability is remarkable enough in its own right—for the cues are often given unconsciously by the human trainer, and detection of such subtle signals requires extremely sharp perception.

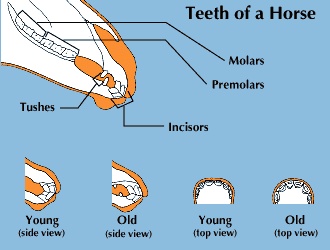

The horse, like other grazing herbivores, has typical adaptations for plant eating: a set of strong, high-crowned teeth, suited to grinding grasses and other harsh vegetation, and a relatively long digestive tract, most of which is intestine concerned with digesting cellulose matter from vegetation. Young horses have milk (or baby) teeth, which they begin to shed at about age two and a half. The permanent teeth, numbering 36 to 40, are completely developed by age four to five years. In the stallion these teeth are arranged as follows on the upper and lower jaws: 12 incisors that cut and pull at grasses; four canines, remnants without function in the modern horse and usually not found in mares; 12 premolars and 12 molars, high prisms that keep moving out of the jaw to replace the surfaces worn off in grinding food.

The horse, like other grazing herbivores, has typical adaptations for plant eating: a set of strong, high-crowned teeth, suited to grinding grasses and other harsh vegetation, and a relatively long digestive tract, most of which is intestine concerned with digesting cellulose matter from vegetation. Young horses have milk (or baby) teeth, which they begin to shed at about age two and a half. The permanent teeth, numbering 36 to 40, are completely developed by age four to five years. In the stallion these teeth are arranged as follows on the upper and lower jaws: 12 incisors that cut and pull at grasses; four canines, remnants without function in the modern horse and usually not found in mares; 12 premolars and 12 molars, high prisms that keep moving out of the jaw to replace the surfaces worn off in grinding food.Under domestication the horse has diversified into three major types, based on size and build: draft horses, heavy limbed and up to 20 hands (200 cm, or 80 inches) high; ponies, by convention horses under 14.2 hands (about 147 cm, or 58 inches) high; and light horses—the saddle or riding horses—which fall in the intermediate size range. Domestic horses tend to be nearsighted, less hardy than their ancestors, and often high-strung, especially thoroughbreds, where intensive breeding has been focused upon speed to the exclusion of other qualities. The stomach is relatively small, and, since much vegetation must be ingested to maintain vital processes, foraging is almost constant under natural conditions. Domestic animals are fed several (at least three) times a day in quantities governed by the exertion of the horse.

Senses

The extremely large eyes (eye, human) placed far back on the elongated head admirably suit the horse for its chief mode of defense: flight. Its long neck and high-set eyes, which register a much wider range than do the eyes of a human being, enable the horse to discern a possible threat even while eating low grasses. Like human vision, the horse's vision is binocular, but only in the narrow area directly forward, and evidence suggests that it does not register colour. While visual acuity is high, the eyes do not have variable focus, and objects at different distances register only on different areas of the retina, which requires tilting movements of the head. The senses of smell and hearing seem to be keener than in human beings. As the biologist George Gaylord Simpson (Simpson, George Gaylord) put it in Horses (1961):

Legs for running and eyes for warning have enabled horses to survive through the ages, although subject to constant attack by flesh eaters that liked nothing better than horse for supper.

Colour (coloration) and pattern

From the dun of the primitive horse has sprung a variety of colours and patterns, some highly variable and difficult to distinguish. Among the most important colours are black, bay, chestnut (and sorrel), palomino, cream, and white.

The black colour is a true black, although a white face marking (blaze) and white ankles (stockings) may occur. The brown horse is almost black but has lighter areas around the muzzle, eyes, and legs. Bay refers to several shades of brown, from red brown and tan to sandy. Bay horses have a black mane, tail, and (usually) stockings (see photograph-->

The black colour is a true black, although a white face marking (blaze) and white ankles (stockings) may occur. The brown horse is almost black but has lighter areas around the muzzle, eyes, and legs. Bay refers to several shades of brown, from red brown and tan to sandy. Bay horses have a black mane, tail, and (usually) stockings (see photograph--> ). Chestnut is similar to bay but with none of the bay's black overtones (see photograph-->

). Chestnut is similar to bay but with none of the bay's black overtones (see photograph--> ). Lighter shades of chestnut are called sorrel. The palomino horse runs from cream to bronze, with a flaxen or silvery mane and tail (see photograph-->

). Lighter shades of chestnut are called sorrel. The palomino horse runs from cream to bronze, with a flaxen or silvery mane and tail (see photograph--> ). The cream is a diluted sorrel, or very pale yellow, nearly white. White in horses is variable, ranging from aging grays (see below) to albinos with blue eyes and pink skin and to pseudoalbinos with a buff mane or with brown eyes. The chief patterns of the white horse are gray, roan, pinto, and appaloosa. Gray horses are born dark brown or black and develop white hairs as they age, becoming almost all white in advanced years. Roan refers to white mixed with other colours at birth: blue roan is white mixed with black; red roan is mixed white and bay; and strawberry roan is white and chestnut. The pinto is almost any spotted pattern of white and another colour; other names, such as paint, calico, piebald, skewbald, overo, and tobiano, refer to subtle distinctions in type of colour or pattern. Appaloosa is another extremely variable pattern, but the term generally refers to a large white patch over the hips and loin, with scattered irregular dark spots (see photograph-->

). The cream is a diluted sorrel, or very pale yellow, nearly white. White in horses is variable, ranging from aging grays (see below) to albinos with blue eyes and pink skin and to pseudoalbinos with a buff mane or with brown eyes. The chief patterns of the white horse are gray, roan, pinto, and appaloosa. Gray horses are born dark brown or black and develop white hairs as they age, becoming almost all white in advanced years. Roan refers to white mixed with other colours at birth: blue roan is white mixed with black; red roan is mixed white and bay; and strawberry roan is white and chestnut. The pinto is almost any spotted pattern of white and another colour; other names, such as paint, calico, piebald, skewbald, overo, and tobiano, refer to subtle distinctions in type of colour or pattern. Appaloosa is another extremely variable pattern, but the term generally refers to a large white patch over the hips and loin, with scattered irregular dark spots (see photograph--> ).

). nutrition

The horse's natural food is grass. For stabled horses, the diet generally consists of hay and grain. The animal should not be fed immediately before or after work, to avoid digestive problems. Fresh water is important, especially when the horse is shedding its winter coat, but the animal should never be watered when it is overheated after working. Oats provide the greatest nutritional value and are given especially to foals. Older horses, whose teeth are worn down, or those with digestive troubles, can be provided with crushed oats. Chaff (minced straw) can be added to the oat ration of animals that eat greedily or do not chew the grain properly. Crushed barley is sometimes substituted in part for oats. Hay provides the bulk of the horse's ration and may be of varying composition according to locale. Mash is bran mixed with water and with various invigorating additions or medications. It may be given to horses with digestive troubles or deficient eating habits. Corn (maize) is used as a fattening cereal, but it makes the horse sweat easily. Salt is needed by the horse at all times and especially when shedding. Bread, carrots, and sugar are tidbits often used to reward an animal by the rider or trainer. In times of poverty horses have adapted to all sorts of food—potatoes, beans, green leaves, and in Iceland even fish—but such foods are not generally taken if other fare is available. A number of commercial feed mixes are available to modern breeders and owners; these mixes contain minerals, vitamins, and other nutrients and are designed to provide a balanced diet when supplemented with hay.

Behaviour

The horse's nervous system is highly developed and gives proof to varying degrees of the essential faculties that are the basis of intelligence: instinct, memory, and judgment. Foals, which stand on their feet a short while after birth and are able to follow their mothers within a few hours, even at this early stage in life exhibit the traits generally ascribed to horses. They have a tendency to flee danger. They express fear sometimes by showing panic and sometimes by immobility. Horses rarely attack and do so either when flight is impossible or when driven to assault a person who has treated them brutally.

Habit governs a large number of their reactions. Instinct, together with a fine sense of smell and hearing, enables them to sense water, fire, even distant danger. An extremely well-developed sense of direction permits the horse to find its way back to its stables even at night or after a prolonged absence. The visual memory of the horse prompts it to shy repeatedly from an object or place where it had earlier experienced fear. The animal's auditory memory, which enabled ancient army horses or hunters to follow the sounds of the bugles, is used in training. When teaching, the instructor always uses the same words and the same tone of voice for a given desired reaction. Intelligent horses soon attach certain movements desired by their trainers to particular sounds and even try to anticipate their rider's wishes.

While instinct is an unconscious reaction more or less present in all individuals of the same species, the degree of its expression varies according to the individual and its development. Most horses can sense a rider's uncertainty, nervousness, or fear and are thereby encouraged to disregard or even deliberately disobey the rider. Highbred animals, which give evidence of greater intelligence than those of low breeding, are capable not only of acts of vengeance and jealousy against their riders but also of expressions of confidence, obedience, affection, and fidelity. They are less willing than a lowbred horse to suffer rough handling or unjust treatment.

Cunning animals have been known to employ their intelligence and physical skill to a determined end, such as opening the latch of a stall or the lid of a chest of oats.

Reproduction and development

The onset of adult sex characteristics generally begins at the age of 16 to 18 months; the horse is considered mature, according to the breed, at approximately three years and adult at five. Fecundity varies according to the breed and may last beyond age 20 with thoroughbreds and to 12 or 15 with other horses. The gestation period is 11 months, 280 days being the minimum in which the foal can be born with expectation to live. As a rule a mare produces one foal per mating, twins occasionally, and triplets rarely. The foal is weaned at six months.

The useful life of a horse varies according to the amount of work it is required to do and the maintenance furnished by its owner. A horse that is trained carefully and slowly and is given the necessary time for development may be expected to serve to an older age than a horse that is rushed in its training. Racehorses that enter into races at the age of two rarely remain on the turf beyond eight. Well-kept riding horses, on the contrary, may be used more than 20 years.

The life span of a horse is calculated at six to seven times the time necessary for his physical and mental development; that is, 30 to 35 years at the utmost, the rule being about 20 to 25 years. Ponies generally live longer than larger horses. There are a number of examples of horses that have passed the usual limit of age. The veterinary university of Vienna conserves the skeleton of a thoroughbred mare of 44 years of age. There have been reports made of horses living to the early 60s in age.

Diseases (animal disease) and parasites

Horses are subjected to a number of contagious diseases, such as influenza, strangles, glanders, equine encephalomyelitis, and swamp fever. Their skin is affected by parasites, including certain mites, ticks, and lice. Those with sensitive skin are especially subject to eczemas and abscesses, which may result from neglect or contamination. Sores caused by injuries to the skin from ill-fitting or unclean saddles and bridles are common ailments. The horse's digestive tract is particularly sensitive to spoiled feed, which causes acute or chronic indigestion, especially in hot weather. Worms can develop in the intestine and include the larvae of the botfly, pinworms, tapeworms, and roundworms (ascarids). Overwork and neglect may predispose the horse to pneumonia and rheumatism. The ailment known as roaring is an infection of the larynx that makes the horse inhale noisily; a milder form causes the horse to whistle. Chronic asthma, or “broken wind,” is an ailment that is considered to be all but incurable. A horse's legs and feet are sensitive to blows, sprains, and overwork, especially if the horse is young or is worked on hard surfaces. Lameness may be caused by bony growths, such as splints, spavins, and ringbones, by soft-tissue enlargements, known as windgalls, thoroughpins, and shoe boils, and by injury to the hooves, including sand crack, split hoof, tread thrush, and acute or chronic laminitis.

Breeds (animal breeding) of horses

The first intensively domesticated horses were developed in Central Asia. They were small, lightweight, and stocky. In time, two general groups of horses emerged: the southerly Arab-Barb types (from the Barbary coast) and the northerly, so-called cold-blooded types. When, where, and how these horses appeared is disputed. Nevertheless, all modern breeds—the light, fast, spirited breeds typified by the modern Arabian, the heavier, slower, and calmer working breeds typified by the Belgian, and the intermediate breeds typified by the Thoroughbred—may be classified according to where they originated (e.g., Percheron, Clydesdale, and Arabian), by the principal use of the horse (riding, draft, coach horse), and by their outward appearance and size (light, heavy, pony).

Light horses

Arabian (Arabian horse)

Its long history is obscured by legend, but the Arabian breed, prized for its stamina, intelligence, and character, is known to have been developed in Arabia by the 7th century AD. It is a compact horse with a small head, protruding eyes, wide nostrils, marked withers, and a short back. It usually has only 23 vertebrae, while 24 is the usual number for other breeds. Its legs are strong with fine hooves. The coat, tail, and mane are of fine silky hair. While many colours are possible in the breed, gray prevails. The most famous stud farm is in the region of Najd, Saudi Arabia, but many fine Arabian horses are bred in the United States.

Its long history is obscured by legend, but the Arabian breed, prized for its stamina, intelligence, and character, is known to have been developed in Arabia by the 7th century AD. It is a compact horse with a small head, protruding eyes, wide nostrils, marked withers, and a short back. It usually has only 23 vertebrae, while 24 is the usual number for other breeds. Its legs are strong with fine hooves. The coat, tail, and mane are of fine silky hair. While many colours are possible in the breed, gray prevails. The most famous stud farm is in the region of Najd, Saudi Arabia, but many fine Arabian horses are bred in the United States. Thoroughbred

The history of the English Thoroughbred is a long one. Records indicate that a stock of Arab and Barb horses was introduced into England as early as the 3rd century. Conditions of climate, soil, and water favoured development, and selective breeding was long encouraged by those interested in racing. Under the reigns of James I and Charles I, 43 mares (the Royal Mares) were imported into England, and a record, the General Stud Book, was begun in which are inscribed only those horses that may be traced back to the Royal Mares in direct line, or to only three other horses imported to England: the Byerly Turk (imported in 1689), the Darley Arabian (after 1700), and the Godolphin Barb (also known as the Godolphin Arabian, imported about 1730). The English Thoroughbred has since been introduced to most countries, where it is bred for racing or used to improve local breeds. The Thoroughbred has a small fine head, a deep chest, and a straight back. Its legs have short bones that allow a long easy stride, and its coat is generally bay or chestnut, rarely black or gray.

The history of the English Thoroughbred is a long one. Records indicate that a stock of Arab and Barb horses was introduced into England as early as the 3rd century. Conditions of climate, soil, and water favoured development, and selective breeding was long encouraged by those interested in racing. Under the reigns of James I and Charles I, 43 mares (the Royal Mares) were imported into England, and a record, the General Stud Book, was begun in which are inscribed only those horses that may be traced back to the Royal Mares in direct line, or to only three other horses imported to England: the Byerly Turk (imported in 1689), the Darley Arabian (after 1700), and the Godolphin Barb (also known as the Godolphin Arabian, imported about 1730). The English Thoroughbred has since been introduced to most countries, where it is bred for racing or used to improve local breeds. The Thoroughbred has a small fine head, a deep chest, and a straight back. Its legs have short bones that allow a long easy stride, and its coat is generally bay or chestnut, rarely black or gray.Asian (Asia)

Asian breeds were strongly influenced by Arabian or Persian breeds, which together with the horses of the steppes produced small, plain-looking horses of great intelligence and endurance. Among them are the Tartar, Kirghis, Mongol, and Cossack horses. A Persian stallion and a Dutch mare produced the Orlov trotter in 1778, named after Count Orlov, the owner of the stud farm where the mating took place.

Anglo-Arab

The Anglo-Arab breed originated in France with a crossing of English Thoroughbreds to pure Arabians. The matings produced a horse larger than the Arabian and smaller than the Thoroughbred, of easy maintenance, and capable of carrying considerable weight in the saddle. Its coat is generally chestnut or bay.

American breeds

The Standardbred (see photograph-->

The Standardbred (see photograph--> ), a breed that excels at the pace and trot, ranks as one of the world's finest harness racers. A powerful, long-bodied horse, the Standardbred was developed during the first half of the 19th century and can be traced largely to the sire Messenger, a Thoroughbred imported from Britain in 1788 and mated to various brood mares in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

), a breed that excels at the pace and trot, ranks as one of the world's finest harness racers. A powerful, long-bodied horse, the Standardbred was developed during the first half of the 19th century and can be traced largely to the sire Messenger, a Thoroughbred imported from Britain in 1788 and mated to various brood mares in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The quarter horse was bred for races (quarter-horse racing) of a quarter of a mile and is said to descend from Janus, a small Thoroughbred stallion imported into Virginia toward the end of the 18th century. It is 14.2 to 16 hands high, with sturdily muscled hindquarters, essential for the fast departure required in short races. It serves as a polo pony equally well as for ranch work.

The quarter horse was bred for races (quarter-horse racing) of a quarter of a mile and is said to descend from Janus, a small Thoroughbred stallion imported into Virginia toward the end of the 18th century. It is 14.2 to 16 hands high, with sturdily muscled hindquarters, essential for the fast departure required in short races. It serves as a polo pony equally well as for ranch work. The Morgan horse originated from a stallion given to Justin Morgan of Vermont around 1795. This breed has become a most versatile horse for riding, pulling carriages, farm labour, and cattle cutting. It was the ideal army charger. It stands about 15 hands high and is robust, good-natured, willing, and intelligent. Its coat is dark brown or liver chestnut.

The Morgan horse originated from a stallion given to Justin Morgan of Vermont around 1795. This breed has become a most versatile horse for riding, pulling carriages, farm labour, and cattle cutting. It was the ideal army charger. It stands about 15 hands high and is robust, good-natured, willing, and intelligent. Its coat is dark brown or liver chestnut. Appaloosa is a colour breed said to have descended in the Nez Percé Indian territory of North America from wild mustangs, which in turn descended from Spanish horses brought to the New World by explorers. The Appaloosa is 14.2 to 15.2 hands high, of sturdy build and of most diverse use; it is especially good in farm work.

Appaloosa is a colour breed said to have descended in the Nez Percé Indian territory of North America from wild mustangs, which in turn descended from Spanish horses brought to the New World by explorers. The Appaloosa is 14.2 to 15.2 hands high, of sturdy build and of most diverse use; it is especially good in farm work.

American breeders have also developed several horses that have specialized gaits. These gaited breeds include the American saddle horse (American Saddlebred horse), the Tennessee walking horse, and the Missouri fox trotting horse. The American saddle horse (see photograph-->

American breeders have also developed several horses that have specialized gaits. These gaited breeds include the American saddle horse (American Saddlebred horse), the Tennessee walking horse, and the Missouri fox trotting horse. The American saddle horse (see photograph--> ) has a small head and spectacular high-stepping movements. It is trained for either three or five gaits. The three-gaited horses perform the walk, trot, and canter; the five-gaited horses in addition perform the rack, a quick, high-stepping four-beat gait, and the slow gait, a somewhat slower form of the rack. Since they are used mainly for shows, their hooves are kept rather long, and the muscles of the tail are often clipped so that the base of the tail is carried high. Chestnut and bay are the usual colours. The Tennessee walking horse (see photograph-->

) has a small head and spectacular high-stepping movements. It is trained for either three or five gaits. The three-gaited horses perform the walk, trot, and canter; the five-gaited horses in addition perform the rack, a quick, high-stepping four-beat gait, and the slow gait, a somewhat slower form of the rack. Since they are used mainly for shows, their hooves are kept rather long, and the muscles of the tail are often clipped so that the base of the tail is carried high. Chestnut and bay are the usual colours. The Tennessee walking horse (see photograph--> )—a breed derived partially from the Thoroughbred, Standardbred, Morgan, and American saddle horse—serves as a comfortable riding mount used to cover great distances at considerable speed. Its specialty is the running walk, a long and swift stride. Bay is the most common colour. The Missouri fox trotting horse (see photograph-->

)—a breed derived partially from the Thoroughbred, Standardbred, Morgan, and American saddle horse—serves as a comfortable riding mount used to cover great distances at considerable speed. Its specialty is the running walk, a long and swift stride. Bay is the most common colour. The Missouri fox trotting horse (see photograph--> ), a breed developed to cover the rough terrain of the Ozark region, is characterized by an unusual gait, called the fox trot, in which the front legs move at a walk while the hind legs perform a trot. The most common colours for this breed are sorrel and chestnut sorrel.

), a breed developed to cover the rough terrain of the Ozark region, is characterized by an unusual gait, called the fox trot, in which the front legs move at a walk while the hind legs perform a trot. The most common colours for this breed are sorrel and chestnut sorrel.Other light breeds

The English Hackney is a light carriage horse, influenced by the Thoroughbred, capable of covering distances of 12 to 15 miles (19 to 24 km) per hour at the trot and canter. It measures 15.2 to 15.3 hands high and is appreciated for its high knee action (see photograph-->

The English Hackney is a light carriage horse, influenced by the Thoroughbred, capable of covering distances of 12 to 15 miles (19 to 24 km) per hour at the trot and canter. It measures 15.2 to 15.3 hands high and is appreciated for its high knee action (see photograph--> ).

).The Cleveland Bay carriage horse, up to 17 hands high and generally bay in colour, is similar to the Yorkshire Coach horse. Both breeds are now used for the sport of driving.

Other versatile breeds include the German Holstein, Hanoverian (see photograph-->

Other versatile breeds include the German Holstein, Hanoverian (see photograph--> ), and East Prussian (Trakehner; see photograph-->

), and East Prussian (Trakehner; see photograph--> ), which serve equally well for riding, light labour, and carriage. These horses, 16 to 18 hands high and of all colours, are now mostly bred for sport.

), which serve equally well for riding, light labour, and carriage. These horses, 16 to 18 hands high and of all colours, are now mostly bred for sport. The Andalusian (see photograph-->

The Andalusian (see photograph--> ), a high-stepping, spirited horse, and the small but enduring Barb produced the Lipizzaner, which was named after the stud farm founded near Trieste, Italy, in 1580. Originally of all colours, the Lipizzaner is gray or, now exceptionally, bay. It is small, rarely over 15 hands high, of powerful build but slender legs, and with long silky mane and tail. Intelligence and sweetness of disposition as well as gracefulness destined it for academic horsemanship, notably as practiced at the Spanish Riding School of Vienna.

), a high-stepping, spirited horse, and the small but enduring Barb produced the Lipizzaner, which was named after the stud farm founded near Trieste, Italy, in 1580. Originally of all colours, the Lipizzaner is gray or, now exceptionally, bay. It is small, rarely over 15 hands high, of powerful build but slender legs, and with long silky mane and tail. Intelligence and sweetness of disposition as well as gracefulness destined it for academic horsemanship, notably as practiced at the Spanish Riding School of Vienna.Heavy breeds (draft animal)

Selected breeds of heavy horses Selected breeds of heavy horsesThe horses used for heavy loads and farm labour descended from the ancient war horses of the Middle Ages. These breeds—including the English Shire (the world's largest horse), Suffolk, and Clydesdale; the French Percheron; the Belgian horse; the German Noriker; and the Austrian Pinzgauer—are now little used for their original purpose, having been almost entirely replaced by the tractor. They usually measure well over 16 hands high, some more than 19 hands. They are of all colours, sometimes spotted, and generally have a very calm temperament.

Ponies (pony)

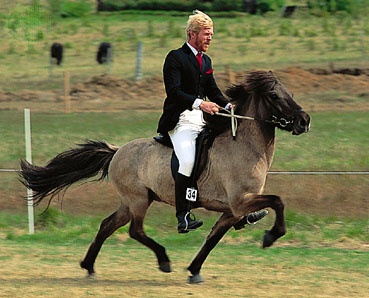

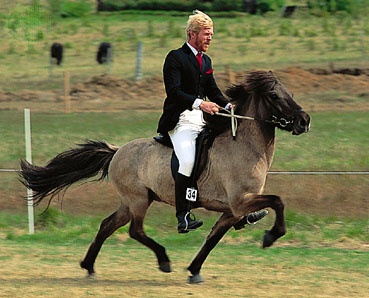

Selected breeds of ponies Selected breeds of poniesPonies are any horses other than Arabians that are shorter than 14.2 hands. They are generally very sturdy, intelligent, energetic, and sometimes stubborn. The coat is of all colours, mainly dark, and the mane and tail are full. Ponies are used for pulling carriages and pack loads and as children's riding horses or pets. There are numerous varieties, including the Welsh, Dartmoor, Exmoor, Connemara, New Forest, Highland, Dale, Fell, pony of the Americas, Shetland (under seven hands high), Iceland (see photograph-->

Selected breeds of ponies Selected breeds of poniesPonies are any horses other than Arabians that are shorter than 14.2 hands. They are generally very sturdy, intelligent, energetic, and sometimes stubborn. The coat is of all colours, mainly dark, and the mane and tail are full. Ponies are used for pulling carriages and pack loads and as children's riding horses or pets. There are numerous varieties, including the Welsh, Dartmoor, Exmoor, Connemara, New Forest, Highland, Dale, Fell, pony of the Americas, Shetland (under seven hands high), Iceland (see photograph--> ), and Norwegian. Ponies of the warmer countries include the Indian, Java, Manila, and Argentine.

), and Norwegian. Ponies of the warmer countries include the Indian, Java, Manila, and Argentine. Originating in the South Tyrol, the Haflinger is a mountain pony, enduring, robust, and versatile, used for all farm labour, for pulling a carriage or sledge (see photograph-->

Originating in the South Tyrol, the Haflinger is a mountain pony, enduring, robust, and versatile, used for all farm labour, for pulling a carriage or sledge (see photograph--> ), and for pack hauling. It is chestnut with a flaxen mane and tail.

), and for pack hauling. It is chestnut with a flaxen mane and tail.Evolution of the horse

The evolutionary lineage of the horse is among the best-documented in all paleontology. The history of the horse family, Equidae (equine), began during the Eocene Epoch, which lasted from about 54.8 to 33.7 million years ago. During the Early Eocene there appeared the first ancestral horse, a hoofed, browsing mammal designated correctly as Hyracotherium but more commonly called Eohippus (dawn horse), the “dawn horse.” Fossils of Eohippus, which have been found in both North America and Europe, show an animal that stood from 4.2 to 5 hands high, diminutive by comparison to the modern horse, with an arched back and raised hindquarters. The legs ended in padded feet with four functional hooves on the forefeet and three on the hindfeet—quite unlike the unpadded, single-hoofed foot of modern equines. The skull lacked the large, flexible muzzle of the modern horse, and the size and shape of the cranium indicate that the brain was far smaller and less complex than that of today's horse. The teeth, too, differed significantly from those of the modern equines, being adapted to a fairly general browser's diet. Eohippus was, in fact, so unhorselike that its evolutionary relationship to the modern equines was at first unsuspected. It was not until paleontologists had unearthed fossils of later extinct horses that the link to Eohippus became clear.

The evolutionary lineage of the horse is among the best-documented in all paleontology. The history of the horse family, Equidae (equine), began during the Eocene Epoch, which lasted from about 54.8 to 33.7 million years ago. During the Early Eocene there appeared the first ancestral horse, a hoofed, browsing mammal designated correctly as Hyracotherium but more commonly called Eohippus (dawn horse), the “dawn horse.” Fossils of Eohippus, which have been found in both North America and Europe, show an animal that stood from 4.2 to 5 hands high, diminutive by comparison to the modern horse, with an arched back and raised hindquarters. The legs ended in padded feet with four functional hooves on the forefeet and three on the hindfeet—quite unlike the unpadded, single-hoofed foot of modern equines. The skull lacked the large, flexible muzzle of the modern horse, and the size and shape of the cranium indicate that the brain was far smaller and less complex than that of today's horse. The teeth, too, differed significantly from those of the modern equines, being adapted to a fairly general browser's diet. Eohippus was, in fact, so unhorselike that its evolutionary relationship to the modern equines was at first unsuspected. It was not until paleontologists had unearthed fossils of later extinct horses that the link to Eohippus became clear.The line leading from Eohippus to the modern horse exhibits the following evolutionary trends: increase in size, reduction in the number of hooves, loss of the foot pads, lengthening of the legs, fusion of the independent bones of the lower legs, elongation of the muzzle, increase in the size and complexity of the brain, and the development of crested, high-crowned teeth suited to grazing. This is not to imply that there was a steady, gradual progression in these characteristics leading inevitably from those of Eohippus to those of the modern horse. Some of these features, such as grazing dentition, appear abruptly in the fossil record, rather than as the culmination of numerous, gradual changes. Eohippus, moreover, gave rise to many now-extinct branches of the horse family, some of which differed substantially from the line leading to the modern equines.

Although Eohippus fossils occur in both the Old and New worlds, the subsequent evolution of the horse took place chiefly in North America. During the remainder of the Eocene, the prime evolutionary changes were in dentition. Orohippus, a genus from the Middle Eocene, and Epihippus, a genus from the Late Eocene, resembled Eohippus in size and in the structure of the limbs. But the form of the cheek teeth—the four premolars and the three molars found in each half of both jaws—had changed somewhat. In Eohippus the premolars and molars were clearly distinct, the molars being larger. In Orohippus the fourth premolar had become similar to the molars, and in Epihippus both the third and fourth premolars had become molarlike. In addition, the individual cusps that characterized the cheek teeth of Eohippus had given way in Epihippus to a system of continuous crests or ridges running the length of the molars and molariform premolars. These changes, which represented adaptations to a more specialized browsing diet, were retained by all subsequent ancestors of the modern horse.

Fossils of Mesohippus, the next important ancestor of the modern horse, are found in the Early and Middle Oligocene of North America (the Oligocene Epoch lasted from about 33.7 to 23.8 million years ago). Mesohippus was far more horselike than its Eocene ancestors—it was larger (averaging about six hands high); the snout was more muzzlelike; and the legs were longer and more slender. Mesohippus also had a larger brain. The fourth toe on the forefoot had been reduced to a vestige, so that both the forefeet and hindfeet carried three functional toes and a foot pad. The teeth remained adapted to browsing.

By the Late Oligocene, Mesohippus had evolved into a somewhat larger form known as Miohippus. The descendants of Miohippus split into various evolutionary branches during the Early Miocene (the Miocene Epoch lasted from about 23.8 to 5.3 million years ago). One of these branches, known as the anchitheres, included a variety of three-toed, browsing horses comprising several genera. Anchitheres were successful, and some genera spread from North America across the Bering land bridge into Eurasia.

It was a different branch, however, that led from Miohippus to the modern horse. The first representative of this line, Parahippus, appeared in the Early Miocene. Parahippus and its descendants marked a radical departure in that they had teeth adapted to eating grass. Grasses were at this time becoming widespread across the North American plains, providing Parahippus with a vast food supply. Grass is a much coarser food than succulent leaves and requires a different kind of tooth structure. The cheek teeth developed larger, stronger crests and became adapted to the side-to-side motion of the lower jaw necessary to grind grass blades. Each tooth also had an extremely long crown, most of which, in the young animal, was buried beneath the gum line. As grinding wore down the exposed surface, some of the buried crown grew out. This high-crowned tooth structure assured the animal of having an adequate grinding surface throughout its normal life span. Adaptations in the digestive tract must have occurred as well, but the organs of digestion are not preserved in the fossil record.

The change from browsing to grazing dentition was essentially completed in Merychippus, which evolved from Parahippus during the Middle and Late Miocene. Merychippus must have looked much like a modern pony. It was fairly large, standing about 10 hands high, and its skull was similar to that of the modern horse. The long bones of the lower leg had become fused; this structure, which has been preserved in all modern equines, is an adaptation for swift running. The feet remained three-toed, but in many species the foot pad was lost, and the two side toes became rather small. In these forms, the large central toe bore the animal's weight. Strong ligaments attached this hoofed central toe to the bones of the ankles and lower leg, providing a spring mechanism that pushed the flexed hoof forward after the impact of hitting the ground. Merychippus gave rise to numerous evolutionary lines during the Late Miocene. Most of these, including Hipparion, Neohipparion, and Nannippus, retained the three-toed foot of their ancestors. One line, however, led to the one-toed Pliohippus, the direct predecessor of Equus. Pliohippus fossils occur in the Early to Middle Pliocene beds of North America (the Pliocene Epoch lasted from about 5.3 to 1.8 million years ago).

Equus—the genus to which all modern equines, including horses, asses, and zebras, belong—evolved from Pliohippus toward the end of the Pliocene. Equus shows even greater development of the spring mechanism in the foot and exhibits straighter and longer cheek teeth. This new form was extremely successful and had spread from the plains of North America to South America and to all parts of the Old World by the Early Pleistocene (the Pleistocene Epoch lasted from about 1,800,000 to 10,000 years ago). Equus flourished in its North American homeland throughout the Pleistocene; then, about 10,000 to 8,000 years ago, Equus disappeared from North and South America. Scholars have offered various explanations for this disappearance, including the emergence of devastating diseases or the arrival of human populations (which presumably hunted the horse for food). Despite these speculations, the reasons for the demise of Equus in the New World remain uncertain. The submergence of the Bering land bridge prevented any return migration of horses from Asia, and Equus was not reintroduced into its native continent until the Spanish explorers brought horses in the early 16th century.

During the Pleistocene the evolution of Equus in the Old World gave rise to all the modern members of the genus. The modern horse, Equus caballus, became widespread from central Asia to most of Europe. Local types of horses, all breeds of this single species, undoubtedly developed, and three of these— Przewalski's horse from central Asia, the tarpan from eastern Europe and the Ukrainian steppes, and the forest horse of northern Europe—are generally credited as being the ancestral stock of the domestic horse. According to this line of thinking, Przewalski's horse and the tarpan formed the basic breeding stock from which the southerly “warm-blooded” horses developed, while the forest horse gave rise to the heavy, “cold-blooded” breeds.

Ed.

Additional Reading

George G. Simpson, Horses (1951, reprinted 1970), a very readable and popular account of the horse family today and through 60,000,000 years of development, with a good bibliography; Margaret C. Self, The Horseman's Encyclopedia, rev. ed. (1963, reprinted 1978), an invaluable collection of information on domestic horses. Breed associations issue pamphlets on selected breeds of horses. See also A Standard Guide to Horse and Pony Breeds, general ed. Elwyn Hartley Edwards (1980), providing information on 150 breeds and types. The Horseman's International Book of Reference, ed. by Jean Froissard and Lily Powell Froissard (1980), is an authoritative source consisting of contributions of international experts; C.E.G. Hope and G.N. Jackson (eds.), The Encyclopedia of the Horse (1973), is a comprehensive reference work discussing, among other specific topics, the horse in mythology, literature, and art. See also John Baskett, The Horse in Art (1980). Special aspects are examined in David P. Willoughby, Growth and Nutrition in the Horse (1975); R.H. Smythe, The Horse: Structure and Movement, 2nd ed., rev. by Peter C. Goody (1972); George H. Waring, Horse Behavior: The Behavioral Traits and Adaptations of Domestic and Wild Horses, Including Ponies (1983); Moyra Williams, Horse Psychology, rev. ed. (1976); and Peter Willett, The Thoroughbred (1970). R.S. Summerhays, Encyclopaedia for Horsemen, 6th ed., rev. by Stella A. Walker (1975), is also a useful reference work. Ed.

- burning at the stake

- burning bush

- Burning of the Gaspee

- Burnley

- Burnouf, Eugène

- Burns

- Burns, Eveline M.

- Burns, George

- Burnside, Ambrose Everett

- Burns, John Elliot

- Burns, Ken

- Burns, Lucy

- Burns metre

- Burns, Robert

- Burns, Sir George, Baronet

- Burns, Tommy

- bur oak

- Burpee, W. Atlee

- Burr, Aaron

- Burragorang, Lake

- Burrard Inlet

- Burri, Alberto

- burro-fat

- Burroughs, Edgar Rice

- Burroughs, John