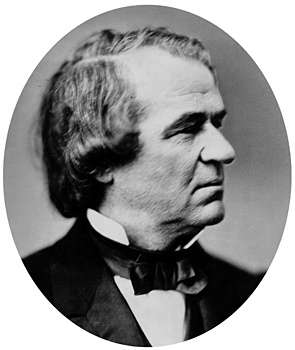

Johnson, Andrew

president of United States

Introduction

born December 29, 1808, Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S.

died July 31, 1875, near Carter Station, Tennessee

17th president of the United States (1865–69), who took office upon the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Lincoln, Abraham) during the closing months of the American Civil War (1861–65). His lenient Reconstruction policies toward the South embittered the Radical Republicans in Congress and led to his political downfall and to his impeachment, though he was acquitted. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)

17th president of the United States (1865–69), who took office upon the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Lincoln, Abraham) during the closing months of the American Civil War (1861–65). His lenient Reconstruction policies toward the South embittered the Radical Republicans in Congress and led to his political downfall and to his impeachment, though he was acquitted. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)Early life and career

Johnson was the younger of two sons of Jacob and Mary McDonough Johnson. Jacob Johnson, who served as a porter in a local inn, as a sexton in the Presbyterian church, and as town constable, died when Andrew was three years old, leaving his family in poverty. His widow took in work as a spinner and weaver to support her family and later remarried. She bound Andrew as an apprentice tailor when he was 14. In 1826, when he had just turned 17, having broken his indenture, he and his family moved to Greeneville, Tennessee. Johnson opened his own tailor shop, which bore the simple sign “A. Johnson, tailor.” (When Johnson was president, he remarked that he still knew how to sew a coat.) He hired a man to read to him while he worked with needle and thread. From a book containing some of the world's great orations he began to learn history. Another subject he studied was the Constitution of the United States, which he was soon able to recite from memory in large part. Harry Truman (Truman, Harry S.) said that Johnson knew the Constitution better than any other president, and many of his later political battles were framed in terms of the constitutionality of proposed legislation. His copy of the Constitution was buried with him.

Johnson never went to school and taught himself how to read and spell. In 1827, now 18 years old, he married 16-year-old Eliza McCardle (Eliza Johnson (Johnson, Eliza)), whose father was a shoemaker. She taught her husband to read and write more fluently and to do arithmetic. She, too, often read to him as he worked. In middle age she contracted what was called “slow consumption” (tuberculosis) and became an invalid. She rarely appeared in public during her husband's presidency, the role of hostess usually being filled by their eldest child, Martha, wife of David T. Patterson, U.S. senator from Tennessee.

Johnson's lack of formal schooling and his homespun quality were distinct assets in building a political base of poor people seeking a fuller voice in government. His tailor shop became a kind of centre for political discussion with Johnson as the leader; he had become a skillful orator in an era when public speaking and debate was a powerful political tool. Before he was 21, he organized a workingman's party that elected him first an alderman and then mayor of Greeneville. During his eight years in the state legislature (1835–43), he found a natural home in the states' rights Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson (Jackson, Andrew) and emerged as the spokesman for mountaineers and small farmers against the interests of the landed classes. In that role, he was sent to Washington for 10 years as a U.S. representative (1843–53), after which he served as governor of Tennessee (1853–57). Elected a U.S. senator in 1856, he generally adhered to the dominant Democratic views favouring lower tariffs and opposing antislavery agitation. Johnson had achieved a measure of prosperity and owned a few slaves himself. In 1860, however, he broke dramatically with the party when, after Lincoln's election, he vehemently opposed Southern secession. When Tennessee seceded in June 1861, he alone among the Southern senators remained at his post and refused to join the Confederacy. Sharing the race and class prejudice of many poor white people in his state, he explained his decision: “Damn the negroes, I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters.” Although denounced throughout the South, he remained loyal to the Union. In recognition of this unwavering support, Lincoln (Lincoln, Abraham) appointed him (May 1862) military governor of Tennessee, by then under federal control.

The presidency

To broaden the base of the Republican Party to include loyal “war” Democrats, Johnson was selected to run for vice president on Lincoln's reelection ticket of 1864. His first appearance on the national stage was a fiasco. On Inauguration Day he imbibed more whiskey than he should have to counter the effects of a recent illness, and as he swayed on his feet and stumbled over his words, he embarrassed his colleagues in the administration and dismayed onlookers. Northern newspapers were appalled. His detractors later seized on this incident to accuse him of habitual drunkenness. Less than five weeks later he was president.

Thrust so unexpectedly into the White House (April 14, 1865), he was faced with the enormously vexing problem of reconstructing the Union and settling the future of the former Confederate states. Congressional Radical Republicans (Radical Republican), who favoured severe measures toward the defeated yet largely impenitent South, were disappointed with the new president's program with its lenient policies begun by Lincoln and its readmission of seceded states into the Union with few provisions for reform or civil rights for freedmen, who, although emancipated, were destitute, uneducated, and subject to exploitation and mistreatment. (See primary source document: Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon for the Confederate States (Andrew Johnson: Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon for the Confederate States).) This element in Congress was outraged at the return of power to traditional white aristocratic hands and protested the emergence of restrictive black codes (black code) aimed at controlling and suppressing the former slaves. The Republican majority refused to seat the Southern congressmen and set up a Joint Committee of Fifteen on Reconstruction. Johnson viewed their actions as a usurpation of his power, and he believed that continued punitive measures in the South, along with a guarantee of suffrage to blacks, was not supported by majority opinion nationwide. He was reluctant to insist on suffrage for blacks in the South when it had not been granted in the North. He believed that placing power over whites in the hands of former slaves would create an intolerable situation.

Thrust so unexpectedly into the White House (April 14, 1865), he was faced with the enormously vexing problem of reconstructing the Union and settling the future of the former Confederate states. Congressional Radical Republicans (Radical Republican), who favoured severe measures toward the defeated yet largely impenitent South, were disappointed with the new president's program with its lenient policies begun by Lincoln and its readmission of seceded states into the Union with few provisions for reform or civil rights for freedmen, who, although emancipated, were destitute, uneducated, and subject to exploitation and mistreatment. (See primary source document: Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon for the Confederate States (Andrew Johnson: Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon for the Confederate States).) This element in Congress was outraged at the return of power to traditional white aristocratic hands and protested the emergence of restrictive black codes (black code) aimed at controlling and suppressing the former slaves. The Republican majority refused to seat the Southern congressmen and set up a Joint Committee of Fifteen on Reconstruction. Johnson viewed their actions as a usurpation of his power, and he believed that continued punitive measures in the South, along with a guarantee of suffrage to blacks, was not supported by majority opinion nationwide. He was reluctant to insist on suffrage for blacks in the South when it had not been granted in the North. He believed that placing power over whites in the hands of former slaves would create an intolerable situation. Johnson's vetoing of two important pieces of legislation aimed at protecting blacks, an extension of the Freedman's Bureau bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, was disastrous. His vetoes united Moderate and Radical Republicans in outrage and further polarized a situation already filled with acrimony. Congress at first failed to override the Freedman's Bureau veto (a second attempt carried the measure) but succeeded with the Civil Rights Act; it was the first instance of a presidential veto's being overridden. In addition, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, conferring citizenship on all persons born or naturalized in the United States and guaranteeing them equal protection under the law. Against Johnson's objections, the amendment was ratified.

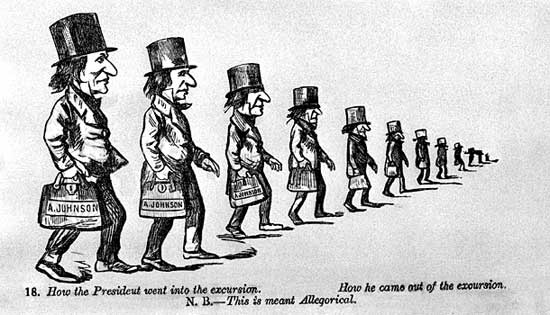

Johnson's vetoing of two important pieces of legislation aimed at protecting blacks, an extension of the Freedman's Bureau bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, was disastrous. His vetoes united Moderate and Radical Republicans in outrage and further polarized a situation already filled with acrimony. Congress at first failed to override the Freedman's Bureau veto (a second attempt carried the measure) but succeeded with the Civil Rights Act; it was the first instance of a presidential veto's being overridden. In addition, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, conferring citizenship on all persons born or naturalized in the United States and guaranteeing them equal protection under the law. Against Johnson's objections, the amendment was ratified. In the congressional elections of 1866, Johnson undertook an 18-day speaking tour into the Midwest, which he called “a swing around the circle,” in order to explain and defend his policies and defeat congressional candidates opposing them. His effort proved a failure. His speeches were often rabble-rousing and ill-tempered as he tried to deal with hecklers sympathetic to the Radicals. In Indianapolis, Indiana, a confrontation with a crowd led to violence in which one man was killed. A result was sweeping electoral victories everywhere for the Radicals. With strong majorities in the House and Senate, they would now have sufficient votes to override any presidential veto of their bills. The president was unable to block legislation that tipped the balance of power to the Congress over the Executive.

In the congressional elections of 1866, Johnson undertook an 18-day speaking tour into the Midwest, which he called “a swing around the circle,” in order to explain and defend his policies and defeat congressional candidates opposing them. His effort proved a failure. His speeches were often rabble-rousing and ill-tempered as he tried to deal with hecklers sympathetic to the Radicals. In Indianapolis, Indiana, a confrontation with a crowd led to violence in which one man was killed. A result was sweeping electoral victories everywhere for the Radicals. With strong majorities in the House and Senate, they would now have sufficient votes to override any presidential veto of their bills. The president was unable to block legislation that tipped the balance of power to the Congress over the Executive.In March 1867 the new Congress passed, over Johnson's veto, the first of the Reconstruction acts, providing for suffrage for male freedmen and military administration of the Southern states. With Reconstruction virtually taken out of his hands, the president, by exercising his veto and by narrowly interpreting the law, managed to delay the program so seriously that he contributed materially to its failure. He maintained that the Reconstruction acts were unconstitutional because they were passed without Southern representation in Congress. Aloof, gruff, and undiplomatic, Johnson constantly antagonized the Radicals. They became his sworn enemies.

Impeachment

Johnson played into the hands of his enemies by an imbroglio over the Tenure of Office Act, passed the same day as the Reconstruction acts. It forbade the chief executive from removing without the Senate's concurrence certain federal officers whose appointments had originally been made by and with the advice and consent of the Senate. The question of the power of the president in this matter had long been a controversial one. (See primary source document: Veto of Tenure of Office Act.) Johnson plunged ahead and dismissed from office Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton (Stanton, Edwin M)—the Radicals' ally within his cabinet—to provide a court test of the act's constitutionality. In response, the House of Representatives voted articles of impeachment against the president—the first such occurrence in U.S. history. While the focus was on Johnson's removal of Stanton in defiance of the Tenure of Office Act, the president was also accused of bringing “into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt, and reproach the Congress of the United States.” The evidence cited was chiefly culled from the speeches he had made during his “swing around the circle.” What was at stake in the trial was not only the fate of a president but the very nature of the federal government. If Congress were able to remove the president, then, many Americans believed, the United States would be a dictatorship run by the leaders of Congress.

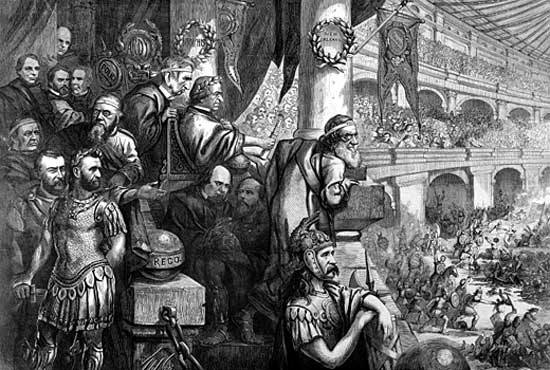

Johnson played into the hands of his enemies by an imbroglio over the Tenure of Office Act, passed the same day as the Reconstruction acts. It forbade the chief executive from removing without the Senate's concurrence certain federal officers whose appointments had originally been made by and with the advice and consent of the Senate. The question of the power of the president in this matter had long been a controversial one. (See primary source document: Veto of Tenure of Office Act.) Johnson plunged ahead and dismissed from office Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton (Stanton, Edwin M)—the Radicals' ally within his cabinet—to provide a court test of the act's constitutionality. In response, the House of Representatives voted articles of impeachment against the president—the first such occurrence in U.S. history. While the focus was on Johnson's removal of Stanton in defiance of the Tenure of Office Act, the president was also accused of bringing “into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt, and reproach the Congress of the United States.” The evidence cited was chiefly culled from the speeches he had made during his “swing around the circle.” What was at stake in the trial was not only the fate of a president but the very nature of the federal government. If Congress were able to remove the president, then, many Americans believed, the United States would be a dictatorship run by the leaders of Congress. In a theatrical proceeding before the Senate, presided over by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (Chase, Salmon P.), the charges proved weak, despite the passion with which they were argued, and the key votes (May 16 and 26, 1868) fell one short of the necessary two-thirds for conviction, seven Republicans voting with Johnson's supporters. These men had been placed under the keenest pressure to vote to convict. One of them, Edmund Ross of Kansas, declared that, as he cast his ballot, “I almost literally looked into my open grave.” When a messenger brought Johnson the news that the Senate had failed to convict him, he wept, declaring that he would devote the remainder of his life to restoring his reputation.

In a theatrical proceeding before the Senate, presided over by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (Chase, Salmon P.), the charges proved weak, despite the passion with which they were argued, and the key votes (May 16 and 26, 1868) fell one short of the necessary two-thirds for conviction, seven Republicans voting with Johnson's supporters. These men had been placed under the keenest pressure to vote to convict. One of them, Edmund Ross of Kansas, declared that, as he cast his ballot, “I almost literally looked into my open grave.” When a messenger brought Johnson the news that the Senate had failed to convict him, he wept, declaring that he would devote the remainder of his life to restoring his reputation.Despite his exoneration, Johnson's usefulness as a national leader was over. During his remaining days in office, he extended his grants of amnesty to all of the former rebels. The vexing problem of black suffrage was addressed by Congress's passage of the Fifteenth Amendment (ratified during the ensuing administration of Ulysses S. Grant (Grant, Ulysses S.)), which forbade denial of suffrage on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” At the 1868 Democratic National Convention, Johnson received a modest number of votes, but he did not actively seek renomination.

After returning to Tennessee, Johnson finally won reelection (1875) as a U.S. senator shortly before he died (he had unsuccessfully run for a Senate seat in 1869 and in 1872 lost a race for a seat in the House of Representatives). Ironically, none of the senators who voted to acquit him was returned to office. In 1926, in the case of United States (Myers v. United States), the Supreme Court handed down an opinion on the tangled question of the president's power to remove officials from office that, in effect, vindicated the position Johnson had taken, declaring the Tenure of Office Act unconstitutional.

Cabinet of President Andrew Johnson

Cabinet of President Andrew Johnson Cabinet of President Andrew JohnsonThe table provides a list of cabinet members in the administration of President Andrew Johnson.

Additional Reading

The personal and official writings of Johnson are collected in LeRoy P. Graf et al. (eds.), The Papers of Andrew Johnson (1967– ).Biographical works include Robert W. Winston, Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot (1928, reprinted 1987); Lloyd Paul Stryker, Andrew Johnson: A Study in Courage (1929, reissued 1971); Lately Thomas, The First President Johnson (1968), which treats both his family life and political career; James E. Sefton, Andrew Johnson and the Uses of Constitutional Power (1980), which attributes Johnson's actions to his unyielding and deep-rooted political philosophy rather than to racism; and Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989), which portrays him as an obstacle to racial progress and positive social change. Brooks D. Simpson, The Reconstruction Presidents (1998), treats Lincoln and Johnson comparatively. A once popular and widely read older interpretation of Johnson's time is Claude G. Bowers, The Tragic Era: The Revolution After Lincoln (1929, reissued 1930). A novel based on Johnson's life is Noel Bertram Gerson, The Yankee from Tennessee (1968). Eric L. McKitrick, Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1960, reprinted 1988); and Albert Castel, The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (1979), offer critical overall assessments of Johnson's presidency. Various aspects are explored in LaWanda Cox and John H. Cox, Politics, Principle, and Prejudice, 1865–1866: Dilemma of Reconstruction America (1963, reissued 1976), finding racial prejudice to be the foundation of much of the political action and organization of the post-Civil War era; William Ranulf Brock, An American Crisis: Congress and Reconstruction, 1865–1867 (1963); Martin E. Mantell, Johnson, Grant, and the Politics of Reconstruction (1973); Michael Les Benedict, A Compromise of Principle: Congressional Republicans and Reconstruction, 1863–1869 (1974), on the struggles between Radical and non-Radical Republicans; Patrick W. Riddleberger, 1866: The Critical Year Revisited (1979, reprinted 1984), on the importance and significance of the 1866 congressional election; and David Warren Bowen, Andrew Johnson and the Negro (1989), tracing the growth of Johnson's positions toward slavery and race and how these attitudes influenced his actions during Reconstruction. The Great Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (1868, reprinted 1974), contains the entire proceedings of the articles of impeachment voted against Johnson and the subsequent trial. Milton Lomask, Andrew Johnson: President on Trial (1960, reprinted 1973), argues that the Radical Republicans were attempting to revise the basic structure of the federal government by initiating Johnson's impeachment. Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (1973), examines the legal aspects of his impeachment and trial and analyzes the motives of the congressmen who voted for acquittal despite a strong case for removing the president from office. Hans L. Trefousse, Impeachment of a President: Andrew Johnson, the Blacks, and Reconstruction (1975), focuses on the motives behind the impeachment and the effects of the acquittal on the efforts of the Radicals to bring about change in the South. A presentation that centres on the drama of Johnson's ordeal is Gene Smith, High Crimes and Misdemeanors: The Impeachment Trial of Andrew Johnson (1977). William H. Rehnquist, Grand Inquests: The Historic Impeachments of Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson (1992), seeks to show that the impeachment process should not be used as a means to dispute policies but rather as an accusation of misconduct. Richard B. McCaslin (compiler), Andrew Johnson (1992), provides an annotated bibliography of more than 2,000 items.

- Hudsonian orogeny

- Hudson, Jennifer

- Hudson Maxim

- Hudson River

- Hudson River school

- Hudson, Rock

- Hudson's Bay Company

- Hudson Strait

- Hudson, Thomas

- Hudson, W H

- Hue

- hue and cry

- Huehuetenango

- Huelva

- Huerta, Adolfo de la

- Huerta, Dolores

- Huerta, Victoriano

- Huesca

- Huesca, Code of

- Huet, Pierre-Daniel

- Huey Long

- Huey P. Newton

- Huey Smith

- Hu Feng

- Huffington Post, The