Malaŵi

Introduction

officially Republic of Malaŵi, formerly Nyasaland

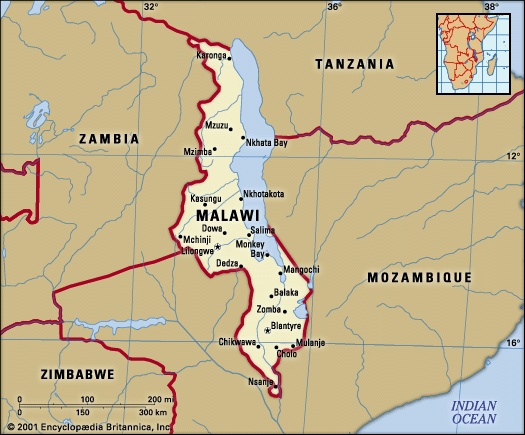

Malawi, flag oflandlocked country in southeastern Africa. A country of spectacular highlands and extensive lakes, it occupies a narrow, curving strip of land along the East African Rift Valley. Stretching about 520 miles (840 kilometres) from north to south, it has a width varying from 5 to 100 miles and is bordered by Tanzania to the north, Mozambique to the east and south, and Zambia to the west. Lake Nyasa (known in Malaŵi as Lake Malaŵi) accounts for more than one-fifth of the country's total area. In 1975 the capital was moved from Zomba in the south to Lilongwe in a more central location.

Most of Malaŵi's population engages in cash-crop and subsistence agriculture. The country's exports consist of the produce of both small landholdings and large tea and tobacco estates. Malaŵi has successfully attracted foreign capital investment, has made great strides in the exploitation of its natural resources, and is one of the few African countries to regularly produce food surpluses. Yet its population suffers from chronic malnutrition, high rates of infant mortality, and grinding poverty—a paradox often attributed to an agricultural system that favours large estate owners.

The land

Relief

While Malaŵi's (Malaŵi) landscape is highly varied, four basic regions can be identified: the East African (East African Rift System) (or Great) Rift Valley, the central plateaus, the highlands, and the isolated mountains. The East African Rift Valley—by far the dominant feature of the country—is a gigantic troughlike depression running through the country from north to south and containing Lake Malaŵi (Nyasa, Lake) (north and central) and the Shire River valley (south). The lake's littoral, situated along the western and southern shores and ranging from 5 to 15 miles in width, covers about 8 percent of the total land area and is dotted with swamps and lagoons. The Shire valley stretches some 250 miles from the southern end of Lake Malaŵi at Mangochi to Nsanje at the Mozambique border and contains Lake Malombe at its northern end. The plateaus of central (Central Region Plateau) Malaŵi rise to an altitude of 2,500 to 4,500 feet (760 to 1,370 metres) and lie just west of the Lake Malaŵi littoral; the plateaus cover about three-quarters of the total land area. The highland areas are mainly isolated tracts that rise as much as 8,000 feet above sea level. They comprise the Nyika (Nyika Plateau), Viphya (Viphya Mountains), and Dowa Highlands and Dedza-Kirk (Kirk Range) Mountain Range in the north and west and the Shire Highlands in the south. The isolated massifs of Mulanje (Mulanje Mountains) (9,849 feet) and Zomba (Zomba Massif) (6,841 feet) represent the fourth physical region. Surmounting the Shire Highlands, they descend rapidly in the east to the Lake Chilwa–Phalombe plain.

Drainage and soils

The major drainage system is that of Lake Malaŵi, which covers some 11,430 square miles and extends beyond the Malaŵi border. It is fed by the North and South Rukuru, Dwangwa, Lilongwe, and Bua rivers. The Shire River, the lake's only outlet, flows through adjacent Lake Malombe and receives several tributaries before joining the Zambezi River in Mozambique. A second drainage system is that of Lake Chilwa (Chilwa, Lake), the rivers of which flow from the Lake Chilwa–Phalombe plain and the adjacent highlands.

Soils, composed primarily of red earths, with brown soils and yellow gritty clays on the plateaus, are distributed in a complex pattern. Alluvial soils occur on the lakeshores and in the Shire valley, while other soil types include hydromorphic (excessively moist) soils, black clays, and sandy dunes on the lakeshore.

Climate

There are two main seasons—the dry season from May to October and the wet season from November to April. Temperatures vary seasonally as well, and they tend to decrease on average with increasing altitude. Nsanje (Port Herald), in the Shire River valley, has a mean July temperature of 69° F (21° C) and an October mean of 84° F (29° C), while Dedza, which lies at an altitude of more than 5,000 feet, has a July mean of 57° F (14° C) and an October mean of 69° F (21° C). On the Nyika Plateau and on the upper levels of the Mulanje Massif, frosts are not uncommon in July. Annual rainfall is highest over parts of the northern highlands and on the Sapitwa peak of Mulanje Mountain, where it is about 90 inches (2,300 millimetres); it is lowest in the lower Shire valley, where it ranges from 25 to 35 inches (650 to 900 millimetres).

Plant and animal life

The natural vegetation pattern reflects the country's diversity in altitude, soils, and climate. Savanna (grassy parkland) occurs in the dry lowland areas. Open woodland with bark cloth trees, or miombo (leguminous trees unsuitable for timber), is widespread on the infertile plateaus and escarpments. Woodland, with species of acacia tree, covers isolated, more fertile plateau sites and river margins; grass-covered, broad depressions, called madambo (singular: dambo), dot the plateaus; grassland and evergreen forest are found in conjunction on the highlands and on the Mulanje and Zomba massifs.

Malaŵi's natural vegetation, however, has been altered significantly by human activities. Swamp vegetation has given way to agricultural species as swamps have been drained and cultivated. Much of the original woodland has been cleared, and, at the same time, forests of softwoods have been planted in the highland areas. High population density and intensive cultivation of the Shire Highlands have also hindered natural succession there, while wells have been sunk and rivers dammed to irrigate the dry grasslands for agriculture.

Game animals abound only in the game reserves, where antelope, buffalo, elephants, leopards, lions, rhinoceroses, and zebras occur; hippopotamuses live in Lake Malaŵi. The lakes and rivers contain more than 200 species and 13 families of fish. The most common and commercially significant fish include the endemic tilapia, or chambo (nest-building freshwater fish); catfish, or mlamba; and minnows, or matemba.

Settlement patterns

Malaŵi is the most densely populated country in southern Africa, but ironically it is also one of the least urbanized, with 9 out of 10 people living in rural locations. A rural village—called a mudzi—is usually small. Organized around the extended family, it is limited by the amount of water and arable land available in the vicinity. On the plateaus, which support the bulk of the population, the most common village sites are at the margins of madambo, which are usually contiguous with streams or rivers and are characterized by woodland, grassland, and fertile alluvial soils. In highland areas, scattered villages are located near perennial mountain streams and pockets of arable land. The larger settlements of the Lake Malaŵi littoral originated in the 19th century as collection points for slaves and later developed as lakeside ports. Improvements in communication and the sinking of wells in semiarid areas have permitted the establishment of new settlements in previously uninhabited areas. Architecture is also changing; the traditional round, mud-walled, grass-roofed hut is giving way to rectangular brick buildings with corrugated iron roofs.

Urban development began in the colonial era with the arrival of missionaries, traders, and administrators and was further stimulated by the construction of the railway. The only true urban centres are Blantyre-Limbe (Blantyre), Zomba, Mzuzu, and Lilongwe. Although some district centres and missionary stations have an urban appearance, they are closely associated with the rural settlements surrounding them. Blantyre, Malaŵi's industrial and commercial centre, is situated in a depression on the Shire Highlands at an altitude of about 3,400 feet. Zomba, seat of the University of Malaŵi, lies at the foot of Zomba Mountain and is purely of administrative origin. Farther north is Lilongwe, Malaŵi's new capital, which is developing agricultural industries.

The people

Nine major ethnic groups are historically associated with modern Malaŵi—the Chewa, Nyanja, Lomwe, Yao, Tumbuka, Sena, Tonga, Ngoni, and Ngonde (Nyakyusa) (Nkonde). All the African languages spoken belong to the Bantu language family. Chichewa is the national language and English the official language, although English was understood by less than one-fifth of the population at independence. Chichewa is spoken by about two-thirds of the population. Other important languages are Chilomwe, Chiyao, and Chitumbuka.

Some two-thirds of the population are Christian, of which more than half are members of various Protestant denominations and the remainder Roman Catholic. Muslims constitute almost one-fifth of the population, and traditional beliefs are adhered to by nearly everyone else.

The population is growing at a rate well above average for sub-Saharan Africa. The birth rate is one of the highest on the continent, but the death rate is also high, and life expectancy—at 47 years—is significantly below average for a southern African country. With nearly one-half the population younger than age 15, high birth and population-growth rates should continue in the 21st century. By the early 1990s the problem of high population growth was compounded further by the then decade-long influx of refugees from Mozambique—estimated to number about one million—fleeing the civil war in that country.

The economy

The backbone of the Malaŵi economy is agriculture, which regularly accounts for one-third of the gross domestic product and 90 percent of export earnings and which employs more than 80 percent of the working population. Since the mid-1960s, however, the sector has become increasingly concentrated on three cash crops—tobacco, tea, and sugar—and increasingly dependent on the market demand for these commodities. The small industrial sector is geared largely to processing agricultural products, with some limited manufacturing of import substitutes.

The government has sought to strengthen the agricultural sector by encouraging integrated land use, higher crop yields, and irrigation schemes. In pursuit of these goals, several large-scale integrated rural development programs, covering one-fifth of the country's land area, have been put into operation. These projects include extension services; credit and marketing facilities; physical infrastructures such as roads, buildings, and water supplies; health centres; afforestation units; and crop storage and protection facilities. Outside the main program areas, advisory services and educational programs are available, and the Malaŵi Young Pioneers, a national youth movement, trains more than 2,000 young men and women yearly in techniques of rural development.

Both higher incomes in the rural areas and continued public expenditure are factors that government planners hope will increase the purchasing power of the public as a whole and thus provide a stimulus for further industrial development. The government continues to promote the establishment of import-substitute industries, in hopes of reducing reliance on expensive imported goods, strengthening the balance-of-payments situation, and, at the same time, increasing employment opportunities.

Resources

Most of Malaŵi's mineral deposits are neither extensive enough for commercial exploitation nor easily accessible. Some small-scale mining of coal takes place at Livingstonia and Rumphi in the north, and quarrying of limestone for cement production is also important. Exploration and assessment studies continue on other minerals such as apatite, located south of Lake Chilwa; bauxite, on the Mulanje Massif; kyanite, on the Dedza-Kirk Range; vermiculite, south of Lake Malaŵi near Ntcheu; and rare-earth minerals, at Mount Kangankunde northwest of Zomba. Deposits of asbestos, uranium, and graphite are known to exist as well.

More than half of Malaŵi's total land area is potentially arable, though only about one-fourth of it is cultivated regularly. Forests and woodlands cover nearly half of the country, and almost 4,000 square miles are in state-controlled forest reserves.

The lakes and rivers of Malaŵi are estimated to provide more than 60 percent of the country's animal protein intake. Lake Malaŵi, in particular, is a rich source of fish within easy access for most of the country's population.

Malaŵi's water resources are plentiful, although some rural areas are inadequately supplied. Treated water for the major cities of Blantyre and Lilongwe is supplied by the Walker's Ferry Scheme and the Kamuzu Dam, respectively. Most of the rivers are seasonal, but a few large ones, particularly the Shire River along its middle course, have a considerable irrigation and electricity-generating potential. The total hydroelectric potential of the country is estimated to be about 1,200 megawatts, of which more than 500 megawatts can be generated on the Shire River alone. Present power demands, which represent only about 10 percent of potential capacity, are met by the Nkula Falls (two plants) and Tedzani Falls hydroelectric schemes and by diesel plants.

Agriculture, fishing, and forestry

The most important agricultural export products are tobacco, tea, sugar, and peanuts (groundnuts). Tea is grown on plantations on the Shire Highlands by the largest proportion of the country's salaried labour force. Tobacco, by far the most important export, is raised largely on the central plateau on large estates. Corn (maize) is the principal food crop and is typically grown with beans, peas, and peanuts throughout the country by virtually all smallholders. Other important crops are cotton, cassava, coffee, and rice. Although the major share of commercial crop production and nearly one-fifth of all cultivated acreage is on large estates, most farms are small, averaging less than 3 acres (1.2 hectares). Smallholder cash crops are purchased and marketed by the Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation; a few cooperative societies purchase and market produce.

Lake Malaŵi is the major source of Malaŵi's fishing industry, but Lakes Chilwa and Malombe and the Shire River also contribute significantly to the annual catch. The industry supplies mainly a local market, but some fish are exported to neighbouring countries.

Since the early 1970s the government has sponsored the development of several large timber and pulpwood plantations aimed at making the country self-sufficient in construction grades of timber. Pine and eucalyptus have also been planted extensively in the northern Viphya Mountains to supply a large pulp and paper project in the region. Sawn poles, posts, and manufactured wooden items are produced largely for the domestic market, although some forest products are exported.

Industry

Development of the country's industrial base was accorded high priority at independence, and Malaŵi now satisfies much of its domestic need for products such as cotton textiles, canned foodstuffs, beer, edible oils, soaps, sugar, radios, hoes, and shoes, all of which previously had to be imported. The main demand for electric power is in the industrial areas of the south near Blantyre, where electricity consumption has steadily multiplied; the industrial area of Lilongwe; the vast sugar estates of Sucoma and Dwangwa; and the pulpwood scheme of Viphya.

Exploitation of bauxite, Malaŵi's most economically important mineral reserve, will depend on an increased hydroelectric capacity to meet the demand of bauxite smelting for abundant cheap electric power. Only such an energy supply could offset the heavy costs of transporting the ore from its remote location to be processed into alumina and then of transporting the alumina to the coast for export.

Trade and finance

About two-thirds of Malaŵi's foreign-exchange earnings are derived from exports of tobacco, of which Malaŵi is the second largest producer in Africa (after Zimbabwe). The main purchaser of its tobacco—as well as of its second major export, tea—is the United Kingdom. Sugar and cotton are the country's other major exports. Diesel fuel and petroleum, fertilizers, consumer goods, machinery and transport equipment, and medical supplies are the main imports. South Africa, Japan, the United States, Germany, and The Netherlands are Malaŵi's other major trading partners.

There are two commercial banks—the National Bank of Malaŵi and the Commercial Bank of Malaŵi. The Reserve Bank of Malaŵi is the central bank of the country. Other financial institutions include the Post Office Savings Bank, the New Building Society, and finance houses. Among the several insurance companies, only one is locally based.

Soon after independence, the government developed an economic policy that was stringently anti-inflationary, arising from the need to reduce the deficit in public expenditure and to maintain the level of foreign-exchange reserves. In budgetary policies maximum restraint, consistent with development needs and planned reduction of grants-in-aid from the United Kingdom, was exercised.

The main emphasis continues to be directed toward agricultural export production and the completion of investment projects, while at the same time maintaining a favourable balance of trade. Malaŵi's development strategy emphasizes concern for the public sector only insofar as it does not interfere with the private sector. Developmental priority is given to transport, agriculture, education, and housing.

A small annual tax is payable by all men over 18 years of age unless they are liable to other taxes. Employees pay an income tax. Local companies pay taxes at a fixed rate of chargeable income, and companies incorporated outside Malaŵi pay a small additional tax.

There is no sizable industrial labour force. Some 20 trade unions and employer associations are connected with such enterprises as the tea plantations, the building and construction industry, road transport, and railways. The Ministry of Labour plays a significant role in maintaining good relations between employers and employees.

Transportation

Malaŵi has road connections to Chipata on the Zambian border; to Harare, Zimbabwe, via Mwanza and Tete; and to several points on the Mozambique border. The backbone of the road system is represented by a road running from Blantyre in the south to Lilongwe in the west. A lakeshore highway runs roughly parallel to the inland highway from Mangochi to Karonga.

Of Malaŵi's two railway links to the sea, the first stretches more than 570 miles from Lilongwe eastward to the port of Beira on the Mozambique coast; an extension from Lilongwe to Mchinji, on the Zambia border, was completed in 1980. The second railroad joins the Salima-Blantyre line at Nkaya Junction to the south of Balaka and travels due east to link with the Mozambique Railways system at Cuamba, whence it continues to the port of Nacala. Increased guerrilla activity in Mozambique after 1981, including attacks on these rail lines, forced Malaŵi to seek alternative, much longer routes to the sea, first through South Africa and then through Tanzania, adding substantially to its freight transport costs. By the early 1990s, traffic had again resumed slowly through Mozambique as Malaŵian and Mozambican troops were more able to suppress rebel attacks.

Of the rivers, only the Shire is partially navigable, all other streams being broken by rapids and cataracts. Lake Malaŵi has long been used as a means of inexpensive transportation. A passenger and cargo service that operates on the lake is linked to the Chipoka railway junction about 17 miles south of Salima. The main ports on the lake are Monkey Bay, Nkhotakota, Nkhata Bay, and Likoma Island.

Air Malaŵi, the national airline, operates services from the main airport at Chileka, 11 miles from Blantyre, to several foreign countries and neighbouring African capitals.

Administration and social conditions

Government

Malaŵi's original constitution of 1966 was replaced with a provisional constitution in 1994, which was officially promulgated in 1995. It provides for a president, who is limited to serving no more than two five-year terms, and up to two vice-presidents, all of whom are elected by universal suffrage. The president serves as head of both state and government. The cabinet is appointed by the president. The legislature, the National Assembly, is unicameral; its members are also elected by universal suffrage and serve five-year terms. The 1995 constitution also provided for the creation of an upper legislative chamber, but it was not established by the target completion date in 1999; a proposal to cancel plans for the creation of such a chamber was passed by the National Assembly in 2001.

The country is divided into 27 administrative districts. The local government system consists of district assemblies. The judiciary consists of magistrate's courts; the High Court, which has unlimited jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters; and the Supreme Court of Appeal, which hears appeals from the High Court.

Malaŵi was a de facto one-party state from August 1961, when the first general elections were held, until 1966, when the constitution formally recognized the Malaŵi Congress Party as the sole political organization. The 1966 constitution was amended in 1993 to allow for a multiparty political system, and since then several other political parties have emerged, with the United Democratic Front (UDF) quickly becoming the most prominent.

Health and welfare

Health facilities include two central hospitals, district hospitals, rural clinics, Zomba Mental Hospital, and Kochira Leprosarium. Common diseases include malaria, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Malaŵi is also affected by a relatively high incidence of AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), particularly in the urban areas, which threatens to tax the country's overburdened health-care system even more. Malaŵi has the highest infant mortality rate in southern African and one of the highest population-to-physician ratios in all of sub-Saharan Africa.

An acute shortage of housing has existed for several years in urban areas. The Malaŵi Housing Corporation has launched several projects to build houses and develop traditional housing areas.

Education

Elementary education is not compulsory, and only about one-half of all eligible children attend primary school. Despite this low proportion, Malaŵi's primary schools feature one of the highest student-teacher ratios in Africa. Postprimary education comprises a four-year secondary-school course that can lead to a university education. The Malaŵi Correspondence College is available to students unable to attend regular secondary school. There are also institutions for teacher training and for technical and vocational training. The Kamuzu Academy at Mtunthama is a secondary school for gifted children. The University of Malaŵi, founded in 1964, has four constituent colleges.

Elementary education is not compulsory, and only about one-half of all eligible children attend primary school. Despite this low proportion, Malaŵi's primary schools feature one of the highest student-teacher ratios in Africa. Postprimary education comprises a four-year secondary-school course that can lead to a university education. The Malaŵi Correspondence College is available to students unable to attend regular secondary school. There are also institutions for teacher training and for technical and vocational training. The Kamuzu Academy at Mtunthama is a secondary school for gifted children. The University of Malaŵi, founded in 1964, has four constituent colleges.Cultural life

Though under the impact of modernization, Malaŵi's traditional culture is characterized by continuity as well as change, and the traditional life of the village has remained largely intact. One of the most distinctive features of Malaŵi culture is the enormous variety of traditional songs and dances (dance) that use the drum as the major musical instrument. Among the most notable of these dances are ingoma and gule wa mkulu for men and chimtali and visekese for women. There are various traditional arts and crafts, including sculpture in wood and ivory. There are two museums—the Museum of Malaŵi in Blantyre and a smaller one in Mangochi. While various cultural activities are organized by the Ministry of Youth and Culture, the University of Malaŵi Travelling Theatre, and other groups in Blantyre, the radio from Zomba and Lilongwe has proved to be the most effective means of bringing traditional and modern plays to the rural population.

History

The paleontological record of human cultural artifacts in Malaŵi dates back more than 50,000 years, although known fossil remains of early Homo sapiens belong to the period between 8000 and 2000 BC. These prehistoric forebears have affinities to the San (Bushmen) of southern Africa and were probably ancestral to the Twa and Fula, whom Bantu-speaking peoples claimed to have found when they invaded the Malaŵi region between the 1st and 4th centuries AD. From then to about AD 1200, Bantu settlement patterns spread, as did ironworking and the slash-and-burn method of cultivation. The identity of these early Bantu-speaking inhabitants is uncertain. According to oral tradition, names such as Kalimanjira, Katanga, and Zimba are associated with them.

With the arrival of another wave of Bantu-speaking peoples between the 13th and 15th centuries AD, the recorded history of the Malaŵi region began. These peoples migrated into the region from the north, and they interacted with and assimilated the earlier pre-Bantu and Bantu inhabitants. The descendants of these peoples maintained a rich oral history, and, from 1500, written records were kept in Portuguese and English.

Among the notable accomplishments of the last group of Bantu immigrants was the creation of political states or the introduction of centralized systems of government. They established the Maravi Confederacy about 1480. During the 16th century, the confederacy encompassed the greater part of what is now central and southern Malaŵi, and, at the height of its influence in the 17th century, its system of government affected peoples in the adjacent areas of modern Zambia and Mozambique. North of the Maravi territory, the Ngonde (Nyakyusa) founded a kingdom about 1600. In the 18th century, a group of immigrants from the eastern side of Lake Malaŵi created the Chikulamayembe state to the south of the Ngonde.

The precolonial period witnessed other important developments. In the 18th and 19th centuries, better and more productive agricultural practices were adopted. In some parts of the Malaŵi region, shifting cultivation of indigenous varieties of millet and sorghum began to give way to more intensive cultivation of crops with a higher carbohydrate content, such as corn, cassava, and rice.

The independent growth of indigenous governments and improved economic systems was severely disturbed by the development of the slave trade in the late 18th century and by the arrival of foreign intruders in the late 19th century. The slave trade in Malaŵi increased dramatically between 1790 and 1860 because of the growing demand for slaves on Africa's east coast. Swahili-speaking people from the east coast and the Ngoni and Yao peoples entered the Malaŵi region between 1830 and 1860 as traders or as armed refugees fleeing the Zulu states to the south. All of them eventually created spheres of influence within which they became the dominant ruling class. The Swahili speakers and the Yao also played a major role in the slave trade.

Islam (Islāmic world) spread into Malaŵi from the east coast. It was first introduced at Nkhotakota by the ruling Swahili-speaking slave traders, the Jumbe, in the 1860s. Traders returning from the coast in the 1870s and '80s brought Islam to the Yao of the Shire Highlands. Christianity was introduced in the 1860s by David Livingstone (Livingstone, David) and by other Scottish missionaries who came to Malaŵi after his death in 1873. Missionaries of the Dutch Reformed church of South Africa and the White Fathers of the Roman Catholic church arrived between 1880 and 1910.

Christianity owed its success to the protection given to the missionaries by the colonial government, which the British (British Empire) established after occupying the Malaŵi region in the 1880s and '90s. British colonial authority was welcomed by the missionaries and some African societies but was strongly resisted by the Yao, Chewa, and others. In 1891 the British established the Nyasaland Districts Protectorate, which was called the British Central Africa Protectorate from 1893 and Nyasaland from 1907.

Under the colonial regime, roads and railways were built, the cultivation of cash crops by European settlers was introduced, and inhumane practices were suppressed. On the other hand, the colonial administration did little to enhance the welfare of the African majority because of its commitment to the interests of the European settlers. It failed to develop African agriculture, and many able-bodied men migrated to neighbouring countries to seek employment. Furthermore, between 1951 and 1953 the colonial government decided to join the colonies of Southern and Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, against bitter opposition from their African inhabitants.

These negative features of colonial rule prompted the rise of a nationalist movement. From its humble beginnings during the period between the world wars, African nationalism gathered momentum in the early 1950s. Of special impetus was the imposition of the federation, which nationalists feared as an extension of colonial power. The full force of nationalism as an instrument of change became evident after 1958 under the leadership of Hastings Kamuzu Banda (Banda, Hastings Kamuzu). The federation was dissolved in 1963, and Malaŵi became independent as a member of the Commonwealth of Nations on July 6, 1964.

Two years later, Malaŵi became a republic. Banda was elected president, eventually being made president for life in 1971. The 1966 constitution established a one-party state under the Malaŵi Congress Party (MCP), which in turn was controlled by Banda, who consistently suppressed any opposition for nearly 30 years. The MCP was known as a conservative, pro-Western regime which concentrated its attention on economic development. For more than 10 years, Malaŵi was able to prosper economically before being felled by a confluence of external factors. In an effort to improve the country's economic situation and broaden regional ties, in 1980 Malaŵi joined the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (Southern African Development Community)—a union of majority-ruled nations neighbouring the Republic of South Africa that wished to reduce their dependence on that country. Securing access to transportation routes to coastal ports and building better relationships with its neighbours were primary goals for Malaŵi; however, Banda refused to sever formal diplomatic ties with South Africa, a decision that was not popular with the other leaders in the region.

Meanwhile, pressure for political change was building in Malaŵi. In 1992, public condemnation of the government's record on human rights issues from religious leaders and exiled opposition leaders generated antigovernment demonstrations and riots. Additional pressure from international donors, who withheld financial aid, eventually led to a referendum on democratic reform in 1993, in which Malaŵians voted overwhelmingly to change to a multiparty political system. Later that year the National Assembly stripped Banda of his “president for life” status. The first multiparty presidential election was held in 1994, and Banda lost to Bakili Muluzi, the leader of the main opposition party, the United Democratic Front (UDF).

The country's new constitution, officially promulgated in 1995, provided the structure for transforming Malaŵi into a democratic society, and Muluzi's first term in office brought the country greater democracy and freedom of speech, assembly, and association—a stark contrast to life under Banda's regime. Muluzi also aimed to root out government corruption and reduce poverty and food shortages in the country, although his administration had limited success. Muluzi was reelected in 1999, but his opponent, Gwandaguluwe Chakuamba, challenged the results. The aftermath of the disputed election included demonstrations, violence, and looting. During Muluzi's second term, he drew domestic and international criticism for some of his actions, which were viewed as increasingly autocratic.

Malaŵi's international standing was bolstered in 2000 when the country's small air force quickly responded to the flooding crisis in the neighbouring country of Mozambique, rescuing upwards of one thousand people. However, the country was not as quick to respond to a severe food shortage at home, first noted in the latter half of 2001. By February 2002, a famine had been declared and the government was scurrying to find enough food for its citizens. Unfortunately, much international aid was slow to arrive in the country—or withheld entirely—because of the belief that government mismanagement and corruption contributed to the food shortage. In particular, some government officials were accused of selling grain from the country's reserves at a profit to themselves prior to the onset of the famine.

Muluzi was limited to two terms as president, despite his efforts to amend the constitution to allow further terms. In 2004 his handpicked successor, Bingu wa Mutharika of the UDF, was declared the winner of an election tainted by irregularity and criticized as unfair. Mutharika's administration quickly set out to improve government operations by eliminating corruption and streamlining spending. To that end, Mutharika dramatically reduced the number of ministerial positions in the cabinet and initiated an investigation of several prominent UDF party officials accused of corruption, leading to several arrests. His actions impressed international donors, who resumed the flow of foreign aid previously withheld in protest of the financial mismanagement and corruption of Muluzi's administration.

By the mid-2000s, the country had been negatively affected by the AIDS crisis and the lack of such requisites as economically viable resources, an accessible and well-utilized educational system, and an adequate infrastructure—issues that continued to hamper economic and social progress. However, Mutharika's administration showed potential for leading Malaŵi on a path of meaningful political reform, which in turn promised to further attract much-needed foreign aid.

Ed.

Additional Reading

Overviews of the country can be found in Harold D. Nelson et al., Area Handbook for Malawi (1975, reprinted 1987). Swanzie Agnew and Michael Stubbs (eds.), Malawi in Maps (1972); and Malaŵi Dept. of Surveys, The National Atlas of Malaŵi (1983?), present the country's physical characteristics and natural and human resources in cartographic form. Margaret Read, The Ngoni of Nyasaland (1956, reissued 1970); and T. Cullen Young, Notes on the History of the Tumbuka-Kamanga Peoples in the Northern Province of Nyasaland, 2nd ed. (1970), are ethnographic studies. Horst Dequin, Agricultural Development in Malawi (1969), is a historical study of the period between 1890 and 1967. Economic conditions and politics are discussed in Carolyn McMaster, Malawi: Foreign Policy and Development (1974); and T. David Williams, Malawi: The Politics of Despair (1978).Works chronicling the country's history are John G. Pike, Malawi: A Political and Economic History (1968); B.R. Rafael, A Short History of Malawi, 3rd ed. (1985); Owen J.M. Kalinga, A History of the Ngonde Kingdom of Malawi (1985); Bridglal Pachai, Malawi: The History of the Nation (1973), and Land and Politics in Malawi, 1875–1975 (1978); Bridglal Pachai (ed.), The Early History of Malawi (1972); John McCracken, Politics and Christianity in Malawi, 1875–1940: The Impact of the Livingstonia Mission in the Northern Province (1977); Roderick J. MacDonald (ed.), From Nyasaland to Malawi: Studies in Colonial History (1975); Ian Linden and Jane Linden, Catholics, Peasants, and Chewa Resistance in Nyasaland, 1889–1939 (1974); George Shepperson and Thomas Price, Independent African: John Chilembwe and the Origins, Setting, and Significance of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915 (1958, reissued 1987); and Philip Short, Banda (1974). Ed.