Masaccio

Italian painter

Introduction

byname of Tommaso di Giovanni di Simone Cassai

born Dec. 21, 1401, Castel San Giovanni 【now San Giovanni Valdarno, near Florence, Italy】

died autumn 1428, Rome

important Florentine painter of the early Renaissance whose frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence (c. 1427) remained influential throughout the Renaissance. In the span of only six years, Masaccio radically transformed Florentine painting. His art eventually helped create many of the major conceptual and stylistic foundations of Western painting. Seldom has such a brief life been so important to the history of art.

important Florentine painter of the early Renaissance whose frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence (c. 1427) remained influential throughout the Renaissance. In the span of only six years, Masaccio radically transformed Florentine painting. His art eventually helped create many of the major conceptual and stylistic foundations of Western painting. Seldom has such a brief life been so important to the history of art.Early life and works

Tommaso di Giovanni di Simone Guidi was born in what is now the town of San Giovanni Valdarno, in the Tuscan province of Arezzo, some 40 miles (65 km) southeast of Florence. His father was Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai, a notary, while his mother, Monna Iacopa, was the daughter of an innkeeper. Masaccio's brother Giovanni was also an artist; called lo Scheggia (“the Splinter”), he is known only for several inept paintings. According to the biographer Giorgio Vasari (who is not always reliable), Tommaso himself received the nickname Masaccio (loosely translated as “Big Tom,” or “Clumsy Tom”) because of his absentmindedness about worldly affairs, carelessness about his personal appearance, and other heedless—but good-natured—behaviour.

In the Renaissance, art was often a family enterprise passed down from father to son. It is curious, therefore, that Masaccio and his brother became painters even though none of their immediate forebears were artists. Masaccio's paternal grandfather was a maker of chests (cassoni) which were often painted. It was perhaps through his grandfather's connection with artists that he became one.

One of the most tantalizing questions about Masaccio revolves around his artistic apprenticeship. Young boys, sometimes not yet in their teens, would be apprenticed to a master. They would spend several years in his workshop learning all the necessary skills involved in making many types of art. Certainly Masaccio underwent such training, but there remains no trace of where, when, or with whom he studied. This is a crucial, if unanswerable, problem for an understanding of the painter because in the Renaissance, art was learned through imitation—individuality in the workshop was discouraged. The apprentice would copy the master's style until it became his own. Knowing who taught Masaccio would reveal much about his artistic formation and his earliest work.

From his birthdate in 1401 until Jan. 7, 1422, absolutely nothing is known about Masaccio. On the latter date he entered the Florentine Arte dei Medici e Speziali, the guild to which painters belonged. It is safe to assume that by his matriculation, he was already a full-fledged painter ready to supervise his own workshop. Where he had been between his birth and his 21st year remains, like so much about him, a tantalizing mystery.

Masaccio's earliest extant work is a small triptych dated April 23, 1422, or about three months after he matriculated in the Florentine guild. This triptych, consisting of the Madonna enthroned, two adoring angels, and saints, was painted for the Church of San Giovenale in the town of Cascia, near San Giovanni Valdarno, and is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It displays an acute knowledge of Florentine painting, but its eclectic style, strongly influenced by Giotto and Andrea Orcagna, does not allow us to discern whether Masaccio trained in San Giovanni Valdarno or Florence before 1422. The triptych, nonetheless, is a powerfully impressive demonstration of the skill of the young, but already highly accomplished, artist. Compared to the lyrical, elegant art of Lorenzo Monaco and Gentile da Fabriano, Masaccio's forms are startlingly direct and massive. The triptych's tight, spare composition and the unidealized and vigorous portrayal of the plain Madonna and Child at its centre does not in the least resemble contemporary Florentine painting. The figures do, however, reveal a complete understanding of the revolutionary art of Donatello, the founder of the Florentine Renaissance sculptural style, whose early works Masaccio studied with care. Donatello's realistic sculptures taught Masaccio how to render and articulate the human body and provide it with gestural and emotional expression.

After the Giovenale Triptych, Masaccio's next important work was a sizable, multi-paneled altarpiece for the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine at Pisa in 1426. This important commission demonstrates his growing reputation outside Florence. Unfortunately, the Pisa altarpiece was dismantled in the 18th century and many of its parts lost, but 13 sections of it have been rediscovered and identified in museums and private collections. The altarpiece's images, which include the Madonna and Child (National Gallery, London) originally at its centre, amplify the direct, realistic character of the 1422 triptych. Ensconced in a massive throne inspired by classical architecture, the Madonna is viewed from below and seems to tower over the spectator. The contrast between the bright lighting on her right side and the deep shadow on her left impart an unprecedented sense of volume and depth to the figure.

Originally placed beneath the Madonna, the rectangular panel depicting the Adoration of the Magi (Staatliche Museums, Berlin) is notable for its realistic figures, which include portraits, most likely those of the donor and his family. Like the Madonna and Child, the panel of the Adoration of the Magi is notable for its deep, vibrant hues so different from the prevailing pastels and other light colours found in contemporary Florentine painting. Unlike his fellow artists, Masaccio used colour not as pleasing decorative pattern but to help impart the illusion of solidity to the painted figure.

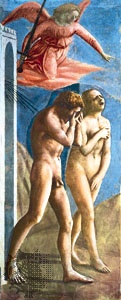

The Brancacci Chapel

Shortly after completing the Pisa Altarpiece, Masaccio began working on what was to be his masterpiece and what was to inspire future generations of artists: the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel (c. 1427) in the Florentine Church of Santa Maria del Carmine. He was commissioned to finish painting the chapel's scenes of the stories of St. Peter after Masolino (1383–1447) had abandoned the job, leaving only the vaults and several frescoes in the upper registers finished. Previously, Masaccio and Masolino were engaged in some sort of loose working relationship. They had already collaborated on a Madonna and Child with St. Anne (Uffizi Gallery, Florence) in which the style of Masaccio, who was the younger of the two, had a profound influence on that of Masolino. It has been suggested, but never proven, that both artists were jointly commissioned to paint the Brancacci Chapel. The question of which painter executed which frescoes in the chapel posed one of the most discussed artistic problems of the 19th and 20th centuries. It is now generally thought that Masaccio was responsible for the following sections: the Expulsion of Adam and Eve (or Expulsion from Paradise), Baptism of the Neophytes, The Tribute Money, St. Peter Enthroned, St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow, St. Peter Distributing Alms, and part of the Resurrection of the Son of Theophilus. (A cleaning and restoration of the Brancacci Chapel frescoes in 1985–89 removed centuries of accumulated grime and revealed the frescoes' vivid original colours.)

The radical differences between the two painters are seen clearly in the pendant frescoes of the Temptation of Adam and Eve by Masolino and Masaccio's Expulsion of Adam and Eve, which preface the St. Peter stories. Masolino's figures are dainty, wiry, and elegant, while Masaccio's are highly dramatic, volumetric, and expansive. The shapes of Masaccio's Adam and Eve are constructed not with line but with strongly differentiated areas of light and dark that give them a pronounced three-dimensional sense of relief. Masolino's figures appear fantastic, while Masaccio's seem to exist within the world of the spectator illuminated by natural light. The expressive movements and gestures that Masaccio gives to Adam and Eve powerfully convey their anguish at being expelled from the Garden of Eden and add a psychological dimension to the impressive physical realism of these figures.

The radical differences between the two painters are seen clearly in the pendant frescoes of the Temptation of Adam and Eve by Masolino and Masaccio's Expulsion of Adam and Eve, which preface the St. Peter stories. Masolino's figures are dainty, wiry, and elegant, while Masaccio's are highly dramatic, volumetric, and expansive. The shapes of Masaccio's Adam and Eve are constructed not with line but with strongly differentiated areas of light and dark that give them a pronounced three-dimensional sense of relief. Masolino's figures appear fantastic, while Masaccio's seem to exist within the world of the spectator illuminated by natural light. The expressive movements and gestures that Masaccio gives to Adam and Eve powerfully convey their anguish at being expelled from the Garden of Eden and add a psychological dimension to the impressive physical realism of these figures.The boldness of conception and execution—the paint is applied in sweeping, form-creating bold slashes—of the Expulsion of Adam and Eve marks all of Masaccio's frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel. The most famous of these is The Tribute Money, which rivals Michelangelo's David as an icon of Renaissance art. The Tribute Money, which depicts the debate between Christ and his followers about the rightness of paying tribute to earthly authorities, is populated by figures remarkable for their weight and gravity. Recalling both Donatello's sculptures and antique Roman reliefs that Masaccio saw in Florence, the figures of Christ and his apostles attain a monumentality and seriousness hitherto unknown. Massive and solemn, they are the very embodiments of human dignity and virtue so valued by Renaissance philosophers and humanists.

The figures of The Tribute Money and the other frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel are placed in settings of remarkable realism. For the first time in Florentine painting, religious drama unfolds not in some imaginary place in the past but in the countryside of Tuscany or the city streets of Florence, with St. Peter and his followers treading the palace-lined streets of an early 15th-century city. By setting his figures in scenes of such specificity, Masaccio sanctified and elevated the observer's world. His depiction of the heroic individual in a fixed and certain place in time and space perfectly reflects humanistic thought in contemporary Florence.

The scene depicted in The Tribute Money is consistently lit from the upper right and thus harmonizes with the actual lighting (light) of the chapel, which comes from a window on the wall to the right of the fresco. The mountain background of the fresco is convincingly rendered using atmospheric perspective; an illusion of depth is created by successively lightening the tones of the more distant mountains, thereby simulating the changes effected by the atmosphere on the colours of distant objects. In The Tribute Money, with its solid, anatomically convincing figures set in a clear, controlled space lit by a consistent fall of light, Masaccio decisively broke with the medieval conception of a picture as a world governed by different and arbitrary physical laws. Instead, he embraced the concept of a painting as a window behind which a continuation of the real world is to be found, with the same laws of space, light, form, and perspective that obtain in reality. This concept was to remain the basic idiom of Western painting for the next 450 years.

The Trinity

The Trinity, a fresco in the Church of Santa Maria Novella, also presents important pictorial innovations that embody contemporary concerns and influences. Painted about 1427, it was probably Masaccio's last work in Florence. It represents the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) set in a barrel-vaulted hall before which kneel two donors. The deep coffered vault is depicted using a nearly perfect one-point system of linear perspective, in which all the orthogonals recede to a central vanishing point. This way of depicting space may have been devised in Florence about 1410 by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (Brunelleschi, Filippo). Masaccio's Trinity is the first extant example of the systematic use of one-point perspective in a painting. One-point perspective fixes the spectator's viewpoint and determines his relation with the painted space. The architectural setting of The Trinity is derived from contemporary buildings by Brunelleschi which, in turn, were much influenced by classical Roman structures. Masaccio and Brunelleschi shared a common artistic vision that was rational, human-scaled and human-centred, and inspired by the ancient world.

Influence

Documentation suggests that Masaccio left Florence for Rome, where he died about 1428. His career was lamentably short, lasting only about six years. He left neither a workshop nor any pupils to carry on his style, but his paintings, though few in number and done for patrons and locations of only middling rank, made an immediate impact on Florence, influencing future generations of important artists. Masaccio's weighty, dignified treatment of the human figure and his clear and orderly depiction of space, atmosphere, and light renewed the idiom of the early 14th-century Florentine painter Giotto (Giotto di Bondone), whose monumental art had been followed but not equaled by the succeeding generations of painters. Masaccio carried Giotto's more realistic style to its logical conclusion by utilizing contemporary advances in anatomy, chiaroscuro, and perspective. The major Florentine painters of the mid-15th century—Filippo Lippi, Fra Angelico, Andrea del Castagno, and Piero della Francesca—were all inspired by the rationality, realism, and humanity of Masaccio's art. But his greatest impact came only 75 years after his death, when his monumental figures and sculptural use of light were newly and more fully appreciated by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, the chief painters of the High Renaissance. Some of Michelangelo's earliest drawings, for example, are studies of figures in The Tribute Money, and through his works and those of other painters, Masaccio's art influenced the entire subsequent course of Western painting.

Additional Reading

Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, trans. by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (1991; originally published in Italian, 1550), provides an early biography; a modern work is John T. Spike, Masaccio (1995). The artist's work is examined in Bruce Cole, Masaccio and the Art of Early Renaissance Florence (1980); and Andrew Ladis, The Brancacci Chapel, Florence (1993). Paul Joannides, Masaccio and Masolino: A Complete Catalogue (1993), includes more than 450 plates and a bibliography of studies on the works of both artists. Bernard Berenson, The Italian Painters of the Renaissance, rev. ed. (1930, reissued 1980); and Bruce Cole, Italian Art, 1250–1550: The Relation of Renaissance Art to Life and Society (1987), place Masaccio's work in historical context. Richard Fremantle and Antonio Quattrone, Masaccio: Catalogo completo (1998, in Italian), is an exhaustive catalog of Masaccio's work. Furthermore, many other works—mostly in Italian—have detailed the restoration of the Brancacci Chapel.

- Andreas Peter Bernstorff, Greve (count) von

- Andreas Peter, Greve (count) von Bernstorff

- Andreas Reyher

- Andreas Rudolf Bodenstein von Carlstadt

- Andreas-Salomé, Lou

- Andreas Schlüter

- Andreas Sigismund Marggraf

- Andreas Vesalius

- Andreas Vokos Miaoulis

- Andre, Carl

- Andre Dubus

- Andrei Liapchev

- Andreina Pagnani

- Andreini, Francesco

- Andreini, Giovambattista

- Andreini, Isabella

- Andrei Okounkov

- Andrei Romanovich Chikatilo

- Andreis, Felix de

- Andrej Hlinka

- Andre Norton

- Andreotti, Giulio

- and Reproduction Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender

- Andres Bonifacio

- Andres Serrano