Middle East, ancient

historical region, Asia

Introduction

history of the region from prehistoric times to the rise of civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and other areas.

Evolution of Middle Eastern civilizations

The high antiquity of civilization in the Middle East is largely due to the existence of convenient land bridges and easy sea lanes passable in summer or winter, in dry or wet seasons. Movement of large numbers of people north of the Caspian Sea was virtually impossible in winter, owing to the severity of the climate; central Eurasia was often too dry in summer. Land passage between Asia and Africa was in early times limited to narrow strips of land in the Isthmus of Suez. Large-scale desert travel was limited to special routes in Iran and in North Africa, both east and west of the Nile Valley.

The high antiquity of civilization in the Middle East is largely due to the existence of convenient land bridges and easy sea lanes passable in summer or winter, in dry or wet seasons. Movement of large numbers of people north of the Caspian Sea was virtually impossible in winter, owing to the severity of the climate; central Eurasia was often too dry in summer. Land passage between Asia and Africa was in early times limited to narrow strips of land in the Isthmus of Suez. Large-scale desert travel was limited to special routes in Iran and in North Africa, both east and west of the Nile Valley.Another reason for the early significance of this area in world history is the fact that the water supply and the climate were ideal for the introduction of agriculture (agriculture, origins of). Several species of grain (cereal) grew wild, and there were marshes and tributary streams that could easily be drained or dammed in order to sow wild wheat and barley. The seed had only to be strewn over a sufficiently moist surface to ensure some kind of crop under normal conditions. It is therefore not surprising that there is evidence of simple agriculture as far back as the 8th or 9th millennium BC, especially in Palestine, where more excavating has been done in early sites than in any other country of the Middle East. Many bone sickle handles and flint sickle edges dating from between c. 9000 and 7000 BC have been found in Palestinian sites.

In Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia, history of) and Iran (Iran, ancient) remains of this period appear in caves on the lower slopes of the Zagros Mountains between western Iran and Iraq. The date of the systematic introduction of irrigation (irrigation and drainage) on a large scale in Mesopotamia is somewhat doubtful because most of the early sites of irrigation culture were covered long ago by accumulation of alluvial soil brought down by the spring floods of the Tigris (Tigris-Euphrates river system) and Euphrates rivers. Archaeologists once thought that all irrigation originated in the foothills of the Zagros and that the earliest true farmers lived in the plains of Iran. But recent excavations and surface explorations have proved that irrigation around the upper Tigris and Euphrates, as well as their tributaries, dates from the early 6th millennium BC (e.g., at al-Kawm on the Upper Euphrates). Small-scale irrigation was practiced in Palestine (e.g., at Jericho) in the 7th millennium BC.

In northern and eastern Mesopotamia, main streams were soon partly diverted during moderate river floods into canals running more or less parallel to the rivers, which could thus be used to irrigate an extensive area. Such deflector dam irrigation avoided the self-destructive weaknesses of large storage dams, in particular the danger of depositing great masses of refractory mud in the storage basin behind the dam. In the north and east considerable urban installations developed at sites such as Nineveh no later than the 5th millennium BC, when southern Mesopotamia was still mostly swampland like the early Egyptian delta. The Euphrates had a much smaller flow of water than the nearby Tigris. The latter was much swifter, however, so that it was potentially more important for irrigation, even though much harder to tame.

The Egyptian Nile (Nile River) had a much more predictable water flow than the Mesopotamian rivers because it flowed through hundreds of miles of swamp, where unusually high annual floods spread out, interfering with navigation but averting the danger of the occasional destructive inundations of Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia, history of) and Egypt to c. 1600 BC

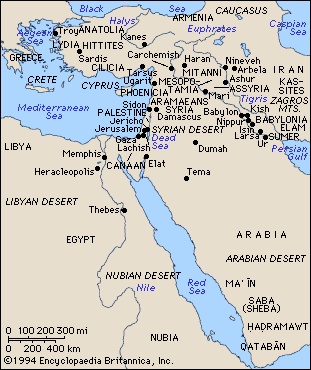

The oldest known urban (urban revolution) and literate culture in the world was developed by the Sumerians (Sumer) in Mesopotamia beginning in the late 4th millennium BC. About 2300 BC a Semitic leader, Sargon I, conquered all of Babylonia and founded the first dynasty of Akkad (Akkadu), which held power for about a century and a half. Sargon and his successors were the first known rulers in southwestern Asia to gain control of the Fertile Crescent as well as of adjacent territories. They sent trading expeditions to central Anatolia and Iran and as far as India and Egypt. After the fall of the dynasty of Akkad there was a Sumerian revival under the 3rd dynasty of Ur (Ur III 【21st–20th centuries】), followed by another influx of Semites. These people founded the first dynasty of Babylon (19th–16th centuries), whose most important king was Hammurabi. In the 17th century new ethnic groups appeared in both Babylonia and Syria-Palestine: Kassites (Kassite) from the Zagros Mountains, Hurrians from what is now Armenia, and Indo-Europeans from Central Asia. This period marked the end of the formative phase of Mesopotamian civilization.

Shortly after 3000 BC the numerous small states that had arisen in the Nile Valley during the 4th millennium were united under the 1st dynasty of Egypt (Egypt, ancient). At this time the Egyptians had already developed a system of writing. Between c. 2686 and c. 2160 BC their country was united under a powerful monarchy (the Old Kingdom) served by a complex bureaucracy.

Toward the end of the 3rd millennium there was a period of disunity, followed by reunification under the 12th dynasty (1991–1786).

During these two centuries Egyptian control was established over Nubia, Libya, Palestine, and southern Syria. Soon after 1800 BC the Egyptian Empire fell apart, and c. 1700 Egypt was overwhelmed by the Asian “Hyksos,” (Hyksos) who ruled the country for a century and a half.

New states and peoples

Before the close of the 16th century BC the native 18th dynasty rose in Egypt; it expelled the Hyksos and founded the New Kingdom. The New Kingdom rulers moved back into Syria-Palestine and came into conflict first with the Hurrian state of Mitanni and later with the Anatolian Hittites (Hittite), who were expanding into Syria from the north in the 14th century BC. The Amarna Letters (diplomatic correspondence written in Babylonian script and language and discovered in Egypt by archaeologists) are an important source of information on this period. In Mesopotamia the dominant powers were Kassite Babylonia and Assyria (which emerged from subjection to Mitanni in the early 14th century BC). Relations between states were governed by elaborate treaties, which were constantly being broken. After the fall of Mitanni (c. 1350) the Hittites and Babylonians both directed their hostility against Assyria. Kassite Babylonia was subjugated by Assyria c. 1230. This, followed by the fall of the Hittite Empire (c. 1200), ended what has been called the first “International Age” in the civilized world.

The latter part of the 13th century BC saw the irruption of new peoples into the Aegean, Anatolia, and the Fertile Crescent; their appearance coincided with the Trojan War, the collapse of the Hittite Empire, and the destruction of many coastal cities of Greece, Cyprus, and Syria-Palestine. Best known of the new settlers from the west are the Phrygians (Phrygia), who occupied most of the old Hittite heartland, and the Philistines (Philistine), who moved into Palestine.

At the same time, in Transjordan and western Palestine, the Hebrews founded a tribal confederation that was changed into a monarchy by Saul and David (c. 1020–960 BC).

In the east the Iranian tribes, led by the Medes, were pouring into Iran from Turkistan. From the south and west came the Semitic Aramaeans (Aramaean). The Aramaeans and Medes were to transform the ancient Middle East.

The Assyrian state suffered an eclipse in the 11th century BC, when the Aramaeans and related tribes occupied most of its territory. It was not until the late 10th century that the Assyrians began to recover, but by 850 they had conquered much of western Media and southern Armenia as well as Babylonia and Syria. In the following centuries, until just before 630, the empire was greatly expanded. It was also highly organized administratively; its language became Aramaic. (Aramaic language)

The Canaanite Phoenicians (Phoenicia) on the Syrian coast re-established their trading communities after the Philistine and Aramaean invasions; in the 10th and 9th centuries they moved out into the Mediterranean, establishing colonies in North Africa and as far west as Spain. Their influence in the western Mediterranean declined after the 6th century. Their Carthaginian colony then took over Phoenician trade in the western and central Mediterranean.

Farther east the Medes and Chaldeans (Chaldea) destroyed the Assyrian Empire at the end of the 7th century. The Chaldean dynasty in Babylonia carried on Assyrian traditions of administration and encouraged commerce; under Nebuchadrezzar II (c. 605–c. 561 BC) their Neo-Babylonian Empire became the most powerful political entity of its time. Its rule extended from the Taurus Mountains in Anatolia to eastern Arabia and deep into southern Iran. This short-lived state made a tremendous impression on contemporaries, especially on the Jews, whose state was destroyed and who were carried into the Babylonian Captivity, and on the Greeks, to whom the glory of Babylon became legendary.

The Achaemenian (Achaemenian Dynasty) Empire and its successors

In the 6th century the Iranian Persians (Iran, ancient) under Cyrus the Great conquered their Median cousins and established the Achaemenian state (549). This was followed by the conquest of Lydia (546) and the Babylonian Empire (539). Aramaic became the official language of the Persian Empire, and its official religion was Zoroastrianism. Cyrus' enlightened policy put an end to the Assyro-Babylonian practice of deporting conquered peoples and trying to destroy all local nationalisms.

At its height the Achaemenian Empire ruled the whole of the Middle East; Greek resistance prevented it from expanding successfully into Europe.

In 334 BC Alexander (Alexander the Great) of Macedon invaded Anatolia and nine years later completed the conquest of the Persian realm. His vast empire was broken up into Macedonian “successor states” after his death. The Seleucid (Seleucid kingdom) kings of Syria controlled most of Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and Iran. About 250 BC the still seminomadic Parthians (Parthia) emerged from a small area southeast of the Caspian Sea. Establishing control over Iran, they declared their independence of the Seleucid Empire and in the 2nd century BC expanded westward into Mesopotamia. In the 3rd century AD the semi-Hellenized Parthians were replaced by the Persian Sāsānians (Sāsānian dynasty). The Sāsānians ruled Iran from AD 224 to 642; they extended its boundaries, reinvigorated its administration and cultural life, and challenged Roman power in the Middle East. In 636 the Sāsānian Empire was conquered by the Muslim Arabs (Arab), bringing to an end the last phase of ancient Middle Eastern civilization.

Pre-Islāmic Arabia.

Arabia was drawn into the orbit of western Asiatic civilization toward the end of the 3rd millennium BC; caravan trade between south Arabia and the Fertile Crescent began about the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. The domestication of the camel around the 12th century BC made desert travel easier and gave rise to a flourishing society in South Arabia, centred around the state of Saba (Sheba (Sabaʾ)). In eastern Arabia the island of Dilmun (Bahrain) had become a thriving entrepôt between Mesopotamia, South Arabia, and India as early as the 24th century BC.

The discovery by the Mediterranean peoples of the monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean made possible flourishing Roman and Byzantine seaborne trade between the northern Red Sea ports and South Arabia, extending to India and beyond.

In the 5th and 6th centuries AD, successive invasions of the Christian Ethiopians and the counterintervention of the Sāsānian kings disrupted the states of South Arabia. The resulting economic decline made the rapid Muslim conquest of the area an easy task in the 7th century.

Elements of civilized culture

Religion

Middle Eastern religious thought had a strong influence on the ancient Greeks. The cosmogonies of Egypt, Babylonia, Phoenicia, and Anatolia were transmitted in part to the West and formed the basis of much of the cosmogonies of Hesiod and the Orphics before 600 BC, as well as the background for the cosmogonies of Thales and Anaximander in the 6th century BC. There is some influence from the Middle East in Pythagorean and Platonic thinking, but it is often hard to define and still harder to prove in detail. From the early 3rd century BC on, the Middle East began to influence Greek thought increasingly. Babylonian astrology influenced Stoic (Stoicism) philosophy, and some Jewish influence on Stoic ethics is likely as well.

Late Egyptian religious speculations were transmitted to the Greeks, especially through the “Physiologists” and Hermetic writers who flourished in Hellenistic Egypt beginning in the 2nd century BC. Astrology and alchemy were transmitted to our time in substantially the forms they received in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt.

With the partial Hellenization of Judaism and its Christian (Christianity) offshoot in the 1st century AD, Jewish influence on the West rapidly became dominant. Most of it came through the Pharisees, but such Jewish sects as the Essenes and Baptists were directly involved.

Even such a heterodox Jewish sect as the Samaritans exerted disproportionately great influence. In the first years of the nascent Christian Church a Samaritan diviner named Simon, later called “Magus,” founded a new faith known as Gnosticism. The Gnostics spread rapidly over both the Roman and Iranian worlds, and by the end of the 3rd century AD they had subdivided into a multitude of different sects that covered a wide spectrum of possible combinations between Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Greco-Roman paganism.

In four centuries Christianity conquered the entire Roman Empire and many outlying regions, thanks to the intensity of its faith and the tenacity with which Christians held to their views, following Jewish models, through the bitterest persecutions.

In the East, Zoroastrianism maintained its hold over the Iranians and neighbouring peoples until the Islāmic conquest, when it was replaced by Islām, itself an offshoot of the monotheistic Judeo-Christian stem.

With the Hebrew Bible (which became the Christian Old Testament) almost the whole of traditional Israelite and early Jewish religion passed into Christianity, which was to a great extent an extension of Judaism. What was lost by the surrender of a large part of Jewish ritual law, with its stress on purity, was compensated by the triumph of monotheism over Greco-Roman polytheism and the transformation of ethical and spiritual ideas in the Greco-Roman world. Judaism itself survived to coexist with Christianity and Islām through all the intervening centuries to our own day.

Science (science, history of) and law

During the 3,000 years of urbanized life in Mesopotamia and Egypt tremendous strides were made in various branches of science and technology. The greatest advances were made in Mesopotamia—very possibly because of its constant shift of population and openness to foreign influence, in contrast to the relative isolation of Egypt and the consequent stability of its population. The Egyptians excelled in such applied sciences as medicine, engineering, and surveying; in Mesopotamia greater progress was made in astronomy and mathematics. The development of astronomy seems to have been greatly accelerated by that of astrology, which took the lead among the quasi-sciences involved in divination. The Egyptians remained far behind the Babylonians in developing astronomy, while Babylonian medicine, because of its chiefly magical character, was less advanced than that of Egypt. In engineering and architecture Egyptians took an early lead, owing largely to the stress they laid on the construction of such elaborate monuments as vast pyramids and temples of granite and sandstone. On the other hand, the Babylonians led in the development of such practical arts as irrigation.

Both sciences and pseudosciences spread from Egypt and Mesopotamia to Phoenicia and Anatolia. The Phoenicians in particular transmitted much of this knowledge to the various lands of the Mediterranean, especially to the Greeks. The direction taken by these influences can be followed from Egypt to Syria, Phoenicia, and Cyprus, thanks to a combination of excavated art forms that prove the direction of movement, as well as to Greek tradition, which lays great stress on what the early Greek philosophers learned from Egypt. Mesopotamian influence can be traced especially through the partial borrowing of Babylonian science and divination by the Hittites and later by the transmission of information through Phoenicia. The Egyptians and Mesopotamians wrote no theoretical treatises; information had to be transmitted piecemeal through personal contacts.

The westward transmission of Babylonian mathematics was associated with that of law (law, philosophy of). All early Babylonian mathematics was transmitted in case form, introduced by a condition followed by its solution. This model appears first in late Sumerian law (cuneiform law): from law it was extended to scientific problems, and the form remained the same until well into the 1st millennium BC. This was true also of such derived systems as Hittite law and the so-called covenant law of Israel, as well as the earliest Greek codes (Draco and Gortyn), all of which are formulated similarly: condition (protasis), secondary condition or conditions, and conclusion (apodosis). The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (Hammurabi, Code of) provides an example: “If a man accuses another man and brings a charge of murder against him but does not prove it, the accuser shall be executed.”

With the spread of case law in such conditional formulation, it was eventually discovered that formulation as generalized propositions or prohibitions was a simpler and more logical means of setting up a coherent code of laws than the case-law formulation (e.g., in the Hebrew Decalogue). The next step was the formulation of generalized geometrical propositions. This was first done by the Ionian Greek Thales (Thales of Miletus) (about 600 BC), whose listing of mathematical propositions in this generalized form instead of as conditional sentences was quite naturally described later as the “discovery” of mathematical theorems. With Thales logical reasoning made a giant step forward from the age of empirical modes of thought.

The Judeo-Christian concept of ethics and morals in law often prevailed in the Roman law of Christian times. Roman forms of law were ultimately adopted in almost the entire Western world, and through their universal sway many biblical approaches to legal problems became dominant.

The alphabet

Of all the accomplishments of the ancient Middle East, the invention of the alphabet is probably the greatest. While pre-alphabetic systems of writing in the Old World became steadily more phonetic, they were still exceedingly cumbersome, and the syllabic systems that gradually replaced them remained complex and difficult. In the early Hyksos period (17th century BC) the Northwestern Semites living in Egypt adapted hieroglyphic characters—in at least two slightly differing forms of letters—to their own purposes. Thus was developed the earliest known purely consonantal alphabet, imitated in northern Syria, with the addition of two letters to designate vowels used with the glottal catch.

This alphabet spread rapidly and was in quite common use among the Northwestern Semites (Canaanites, Hebrews, Aramaeans, and especially the Phoenicians) soon after its invention. By the 9th century BC the Phoenicians were using it in the western Mediterranean, and the Greeks and Phrygians adopted it in the 8th. The alphabet contributed vastly to the Greek cultural and literary revolution in the immediately following period. From the Greeks it was transmitted to other Western peoples. Since language must always remain the chief mode of communication for Homo sapiens, its union with hearing and vision in a uniquely simple phonetic structure has probably revolutionized civilization more than any other invention in history.

Additional Reading

Works treating the rise of civilization in the Middle East specifically include Walther Hinz, The Lost World of Elam: Re-Creation of a Vanished Civilization (1972; originally published in German, 1964), an account of art, religion, and social mores in the Elamite empire; Chester G. Starr, Early Man: Prehistory and the Civilizations of the Ancient Near East (1973), a popular overview of the development of literacy, urban living, art, literature, and religion; Charles L. Redman, The Rise of Civilization: From Early Farmers to Urban Society in the Ancient Near East (1978), on agricultural development, urbanization, and cultural change from 10,000 to 2000 BC; Jack Finegan, Archaeological History of the Ancient Middle East (1979, reissued 1986), a reference work covering history, mythology, and art between 10,000 and 330 BC; and Donald O. Henry, From Foraging to Agriculture (1989), a discussion of the origins of agriculture in the Middle East and surrounding area.

- Sebastião de Carvalho Pombal, marquês de

- Sebastião Salgado

- Sebek

- Sebeknefru

- Sebetwane

- Sebeș

- seborrheic dermatitis

- Sebou River

- Sebring

- Sebüktigin

- Secchi, Pietro Angelo

- secession

- second

- secondary education

- secondary emission

- Second Battle of the Marne

- Second Battle of the Somme

- Second Book of Enoch

- Second Book of Esdras

- Second Coming

- Second Empire style

- Second International

- Second Jewish Revolt

- Second Life

- second messenger