musical instrument

Introduction

any device for producing a musical sound. The principal types of such instruments, classified by the method of producing sound, are percussion (percussion instrument), stringed (stringed instrument), keyboard (keyboard instrument), wind (wind instrument), and electronic (electronic instrument).

Musical instruments are almost universal components of human culture: archaeology has revealed pipes and whistles in the Paleolithic Period and clay drums and shell trumpets in the Neolithic Period. It has been firmly established that the ancient city cultures of Mesopotamia, the Mediterranean, India, East Asia, and the Americas all possessed diverse and well-developed assortments of musical instruments, indicating that a long previous development must have existed. As to the origin of musical instruments, however, there can be only conjecture. Some scholars have speculated that the first instruments were derived from such utilitarian objects as cooking pots (drums) and hunting bows (musical bows); others have argued that instruments of music might well have preceded pots and bows; while in the myths of cultures throughout the world the origin of music has frequently been attributed to the gods, especially in areas where music seems to have been regarded as an essential component of the ritual believed necessary for spiritual survival.

Musical instruments are almost universal components of human culture: archaeology has revealed pipes and whistles in the Paleolithic Period and clay drums and shell trumpets in the Neolithic Period. It has been firmly established that the ancient city cultures of Mesopotamia, the Mediterranean, India, East Asia, and the Americas all possessed diverse and well-developed assortments of musical instruments, indicating that a long previous development must have existed. As to the origin of musical instruments, however, there can be only conjecture. Some scholars have speculated that the first instruments were derived from such utilitarian objects as cooking pots (drums) and hunting bows (musical bows); others have argued that instruments of music might well have preceded pots and bows; while in the myths of cultures throughout the world the origin of music has frequently been attributed to the gods, especially in areas where music seems to have been regarded as an essential component of the ritual believed necessary for spiritual survival. Whatever their origin, the further development of the enormously varied instruments of the world has been dependent on the interplay of four factors: available material, technological skills, mythic and symbolic preoccupations, and patterns of trade and migration. Thus, residents of Arctic regions use bone, skin, and stone to construct instruments; residents of the tropics have wood, bamboo, and reed available; while societies with access to metals and the requisite technology are able to utilize these malleable materials in a variety of ways. Myth and symbolism play an equally important role. Herding societies, for example, which may depend on a particular species of animal not only economically but also spiritually, often develop instruments that look or sound like the animal or prefer instruments made of bone and hide rather than stone and wood, even when all the materials are available. Finally, patterns of human trade and migration have for many centuries swept musicians and their instruments across seas and continents, resulting in constant flux, change, and cross-fertilization and adaptation.

Whatever their origin, the further development of the enormously varied instruments of the world has been dependent on the interplay of four factors: available material, technological skills, mythic and symbolic preoccupations, and patterns of trade and migration. Thus, residents of Arctic regions use bone, skin, and stone to construct instruments; residents of the tropics have wood, bamboo, and reed available; while societies with access to metals and the requisite technology are able to utilize these malleable materials in a variety of ways. Myth and symbolism play an equally important role. Herding societies, for example, which may depend on a particular species of animal not only economically but also spiritually, often develop instruments that look or sound like the animal or prefer instruments made of bone and hide rather than stone and wood, even when all the materials are available. Finally, patterns of human trade and migration have for many centuries swept musicians and their instruments across seas and continents, resulting in constant flux, change, and cross-fertilization and adaptation. The sound (musical sound) produced by an instrument can be affected by many factors, including the material from which the instrument is made, its size and shape, and the way that it is played. For example, a stringed instrument may be struck, plucked, or bowed, each method producing a distinctive sound. A wooden instrument struck by a beater sounds markedly different from a metal instrument, even if the two instruments are otherwise identical. On the other hand, a flute made of metal does not produce a substantially different sound from one made of wood, for in this case the vibrations are in the column of air in the instrument. The characteristic timbre of wind instruments depends on other factors, notably the length and shape of the tube. The length of the tube not only determines the pitch but also affects the timbre: the piccolo, being half the size of the flute, has a shriller sound. The shape of the tube determines the presence or absence of the “upper partials” (harmonic or nonharmonic overtones (overtone)), which give colour to the single note. (For more on the science of sound, see acoustics.)

The sound (musical sound) produced by an instrument can be affected by many factors, including the material from which the instrument is made, its size and shape, and the way that it is played. For example, a stringed instrument may be struck, plucked, or bowed, each method producing a distinctive sound. A wooden instrument struck by a beater sounds markedly different from a metal instrument, even if the two instruments are otherwise identical. On the other hand, a flute made of metal does not produce a substantially different sound from one made of wood, for in this case the vibrations are in the column of air in the instrument. The characteristic timbre of wind instruments depends on other factors, notably the length and shape of the tube. The length of the tube not only determines the pitch but also affects the timbre: the piccolo, being half the size of the flute, has a shriller sound. The shape of the tube determines the presence or absence of the “upper partials” (harmonic or nonharmonic overtones (overtone)), which give colour to the single note. (For more on the science of sound, see acoustics.)This article discusses the evolution of musical instruments, their structure and methods of sound production, and the purposes for which they have been used. Although it focuses on the families of instruments that have been prominent in Western art music, it also includes coverage of non-Western and folk instruments.

General characteristics

Musical instruments have been used since earliest times for a variety of purposes, ranging from the entertainment of concert audiences to the accompaniment of dances, rituals (ritual), work, and medicine. The use of instruments for religious ceremonies has continued down to the present day, though at various times they have been suspect because of their secular associations. The many references to instruments in the Old Testament are evidence of the fact that they played an important part in Jewish worship until for doctrinal reasons they were excluded. It is also clear that the early Christians in the eastern Mediterranean used instruments in their services, since the practice was severely condemned by ecclesiastics, who insisted that the references to instruments in the Psalms were to be interpreted symbolically. Although instruments continue to be banned in Islamic mosques (but not in religious processions or Sufi ritual) and in the traditional Eastern Orthodox church, they play important roles in the ritual of most other societies. For example, Buddhist cultures are rich in instruments, particularly bells and drums (and in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, wind instruments as well).

Musical instruments have been used since earliest times for a variety of purposes, ranging from the entertainment of concert audiences to the accompaniment of dances, rituals (ritual), work, and medicine. The use of instruments for religious ceremonies has continued down to the present day, though at various times they have been suspect because of their secular associations. The many references to instruments in the Old Testament are evidence of the fact that they played an important part in Jewish worship until for doctrinal reasons they were excluded. It is also clear that the early Christians in the eastern Mediterranean used instruments in their services, since the practice was severely condemned by ecclesiastics, who insisted that the references to instruments in the Psalms were to be interpreted symbolically. Although instruments continue to be banned in Islamic mosques (but not in religious processions or Sufi ritual) and in the traditional Eastern Orthodox church, they play important roles in the ritual of most other societies. For example, Buddhist cultures are rich in instruments, particularly bells and drums (and in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, wind instruments as well). Belief in the magical properties of instruments is found in many societies. The Jewish (Judaism) shofar (a ram's horn), which is still blown on Rosh Hashana (New Year) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), must be heard by the congregation. The power of the shofar is illustrated by the story of Joshua at the siege of Jericho: when the priests blew their shofars seven times, the walls of the city fell flat. In India, according to legend, when the deity Krishna played the flute, the rivers stopped flowing and the birds came down to listen. The birds are said to have done the same in 14th-century Italy when the composer Francesco Landini (Landini, Francesco) played his organetto, or portative organ. In China, instruments were identified with the points of the compass, with the seasons, and with natural phenomena. The Melanesian bamboo flute was a charm for rebirth.

Belief in the magical properties of instruments is found in many societies. The Jewish (Judaism) shofar (a ram's horn), which is still blown on Rosh Hashana (New Year) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), must be heard by the congregation. The power of the shofar is illustrated by the story of Joshua at the siege of Jericho: when the priests blew their shofars seven times, the walls of the city fell flat. In India, according to legend, when the deity Krishna played the flute, the rivers stopped flowing and the birds came down to listen. The birds are said to have done the same in 14th-century Italy when the composer Francesco Landini (Landini, Francesco) played his organetto, or portative organ. In China, instruments were identified with the points of the compass, with the seasons, and with natural phenomena. The Melanesian bamboo flute was a charm for rebirth. Many of the instruments used in medieval Europe came from western Asia, and they have retained some of their original symbolism. For example, trumpets (trumpet), long associated with military operations, had a ceremonial function in the establishment of European kings and nobles and were, in fact, regarded as a sign of nobility. In the later Middle Ages and for long afterward, they were associated with kettledrums (kettledrum) (known originally as nakers, after their Arab name, naqqārah), which were often played on horseback, as they still are in some mounted regiments. Trumpet fanfares, heard on ceremonial occasions in the modern world, are a survival of medieval practice.

Many of the instruments used in medieval Europe came from western Asia, and they have retained some of their original symbolism. For example, trumpets (trumpet), long associated with military operations, had a ceremonial function in the establishment of European kings and nobles and were, in fact, regarded as a sign of nobility. In the later Middle Ages and for long afterward, they were associated with kettledrums (kettledrum) (known originally as nakers, after their Arab name, naqqārah), which were often played on horseback, as they still are in some mounted regiments. Trumpet fanfares, heard on ceremonial occasions in the modern world, are a survival of medieval practice.Technological developments

Conventional Western thinking claimed that the earliest instruments were slightly modified natural objects such as bones, shells, or gourds. They played only one pitch and then evolved into more complex forms. However, it appears that bone flutes from Neanderthal caves had finger holes, and recent archaeological finds in China included bone flutes from 7000 BC that not only have seven finger holes but an additional aperture that may have been drilled to correct a poorly placed hole. Thus, early humans appear to have been just as sensitive to pitch and tone colour as were most other sentient creatures, such as birds, cats, dogs, and whales. None of the sounds they heard or made moved from simple to complex. Aztec clay versions of shell trumpets imitated the internal chambers of the nautilus; the instruments' construction may indicate a sophisticated use of the overtone series to obtain varied pitches (as is done on the bugle).

The stretched string of a bow can produce several pitches when it is beaten, and the string can be stopped at points along its length to produce varied sounds. In addition, a resonator such as a pot or gourd is often used to increase the volume of the sound. The player's mouth can add variety to both volume and pitch. A tube of bamboo can become musical when it is struck on the ground, and a set of different-sized tubes can produce a melodic and rhythmic ensemble. Lifting strips of the bark from a tube and adding bridges under the strips creates a melodic zither, for which each strip produces a separate pitch. The sound can be enhanced by placing one end of the tube in a resonator, whether a gourd or a tin can. In sum, the complexity of music depends less on technology than on human imagination.

The stretched string of a bow can produce several pitches when it is beaten, and the string can be stopped at points along its length to produce varied sounds. In addition, a resonator such as a pot or gourd is often used to increase the volume of the sound. The player's mouth can add variety to both volume and pitch. A tube of bamboo can become musical when it is struck on the ground, and a set of different-sized tubes can produce a melodic and rhythmic ensemble. Lifting strips of the bark from a tube and adding bridges under the strips creates a melodic zither, for which each strip produces a separate pitch. The sound can be enhanced by placing one end of the tube in a resonator, whether a gourd or a tin can. In sum, the complexity of music depends less on technology than on human imagination. The first step in the building of any instrument is the selection and preparation of material. Wood used for wind or stringed instruments needs to be seasoned, as do the reeds used in oboes, clarinets, saxophones, and related instruments. Metals, which are widely used for strings, bells, cymbals, gongs, trumpets, and horns, must be manufactured and cast—often originally by secret processes. Next, the construction and tuning (tuning and temperament) of all instruments require skill and craftsmanship: the piercing of a tube to a uniform or expanding width, the flaring of the bell of a wind instrument to increase sonority, the measurement of the bars of a saron (for the Javanese gamelan) or of a glockenspiel, the curvature of the back of a lute or ʿūd, the internal and external structure of the body of a violin, a koto, or even a shakuhachi. All of these involve accurate workmanship from experts in wood and metal and, in many instances, a knowledge of the mathematics of sound.

The first step in the building of any instrument is the selection and preparation of material. Wood used for wind or stringed instruments needs to be seasoned, as do the reeds used in oboes, clarinets, saxophones, and related instruments. Metals, which are widely used for strings, bells, cymbals, gongs, trumpets, and horns, must be manufactured and cast—often originally by secret processes. Next, the construction and tuning (tuning and temperament) of all instruments require skill and craftsmanship: the piercing of a tube to a uniform or expanding width, the flaring of the bell of a wind instrument to increase sonority, the measurement of the bars of a saron (for the Javanese gamelan) or of a glockenspiel, the curvature of the back of a lute or ʿūd, the internal and external structure of the body of a violin, a koto, or even a shakuhachi. All of these involve accurate workmanship from experts in wood and metal and, in many instances, a knowledge of the mathematics of sound. The mathematical basis of accurate tuning systems has been the subject of philosophical and scientific speculation since ancient times; nevertheless, no single system has been deemed perfect (see also tuning and temperament). All practical tuning systems involve a series of compromises, a fact that instrument makers have known for centuries.

The mathematical basis of accurate tuning systems has been the subject of philosophical and scientific speculation since ancient times; nevertheless, no single system has been deemed perfect (see also tuning and temperament). All practical tuning systems involve a series of compromises, a fact that instrument makers have known for centuries. The instrument maker's skill, like that of the cabinetmaker and the silversmith, was developed by long practice, and the principles that determine both tone and intonation were discovered by trial and error. The growth of instrumental playing in 16th-century Europe stimulated the production of instruments to be used not merely for ceremonial and official entertainment but also for social occasions and private pleasure. From this time, records began to be kept of the names of makers, many of whom established family businesses that lasted for several generations. These include, for example, Andrea Amati (Amati Family) (16th century), a violin maker in Cremona, Italy; Hans Ruckers (Ruckers, Hans, The Elder) (late 16th century), a harpsichord maker in Antwerp, Belg.; and Johann Haas (1649–1723), a trumpet maker in Nürnberg (now in Germany). In all literate cultures there are known families or guilds of instrument makers, e.g., for the Middle Eastern ʿūd, South Asian sitar and vina, or Japanese tsuzumi drums. Around the world, instrument makers have long signed their products. Although similar respectful positions are held by instrument makers in cultures without a written record, their reputation is far less likely to spread beyond their particular time and place.

The instrument maker's skill, like that of the cabinetmaker and the silversmith, was developed by long practice, and the principles that determine both tone and intonation were discovered by trial and error. The growth of instrumental playing in 16th-century Europe stimulated the production of instruments to be used not merely for ceremonial and official entertainment but also for social occasions and private pleasure. From this time, records began to be kept of the names of makers, many of whom established family businesses that lasted for several generations. These include, for example, Andrea Amati (Amati Family) (16th century), a violin maker in Cremona, Italy; Hans Ruckers (Ruckers, Hans, The Elder) (late 16th century), a harpsichord maker in Antwerp, Belg.; and Johann Haas (1649–1723), a trumpet maker in Nürnberg (now in Germany). In all literate cultures there are known families or guilds of instrument makers, e.g., for the Middle Eastern ʿūd, South Asian sitar and vina, or Japanese tsuzumi drums. Around the world, instrument makers have long signed their products. Although similar respectful positions are held by instrument makers in cultures without a written record, their reputation is far less likely to spread beyond their particular time and place.Instrument makers have always represented a blend of conservatism with the ability to quickly seize on and use a new constructional technique, a new tool, or a new material. Their contribution to both the history of music and the history of musical instruments has been enormous and little appreciated. The older makers of instruments were craftsmen who took delight in the appearance of their work. In some cases, additions are purely decorative, as when pictures were painted on the inside of harpsichord lids or elaborate patterns were carved onto Indian vinas or inlaid into Persian lutes and drums. The rare set of 9th-century court instruments found in Nara, Japan, includes stunning examples of such artisan skills from all over East Asia. Equal beauty is found on many of the anonymously constructed instruments of Oceania. Often these additions are symbolic or totemic; the patterns on the Australian didjeridu identify the clan of the performer, and shapes and patterns on instruments in New Guinea reflect aspects of the environment and culture. Similarly, the dragon heads on the end of Tibetan and Chinese woodwinds have a symbolic meaning in those cultures. Most modern Western instruments reject ornamentation, but overall design and finish are as important as they have always been.

Modern technology has in many cases simplified or improved the construction of instruments. In the past, for example, the tubes of horns and trumpets were made from a sheet of brass cut to the right width, which was rolled into shape, leaving the edges to be joined by brazing. In modern manufacture the tube is drawn in one piece, and there is no seam. Evolution of design has been particularly notable in the construction of woodwind instruments, not only in the fixing of the metal keys and the mechanism that controls them but also in the piercing of holes in such a way that they are acoustically correct. This achievement was due mainly to the pioneering work of Theobald Boehm (Boehm, Theobald), who was not only a flute maker but also a performer and composer. His system, designed for the flute, was later applied to the clarinet, the oboe, and the bassoon. The early 19th century saw a revolution in the manufacture of brass instruments as well: the addition of pieces of tubing of different lengths through which the air could be directed by the depression of valves (or pistons), enabling an instrument to produce all 12 notes of the chromatic scale, in place of its earlier limitation to the notes of the natural harmonic (overtone) series. Newer techniques of cutting and beating metal have created distinctive modern instruments, such as steel drums.

The discovery of plastics (plastic) in the 20th century also has influenced the manufacturers of instruments; for example, some makers have used plastic instead of quill or leather for the plectra that pluck the strings of the harpsichord, and plastic recorders have been built. Mechanization has made possible the mass production of instruments of all kinds. Insofar as this makes it possible for people to acquire an instrument at a moderate price, mass production is a good thing, and in education it has been beneficial to schools working on a small budget. A natural development has been the provision of kits consisting of the separate parts of an instrument, which can then be assembled by the purchaser. It remains true, however, that the production of an instrument of the finest quality still demands the highest degree of individual skill. A violin glued together from mass-produced parts cannot be the equal of one that has been meticulously constructed from the first by an individual craftsman who will not be satisfied with his work until every detail of it has been tested.

Technology has been of service to music by providing composers with instruments they have asked for, by eliminating some defects of instruments, and by making instruments more widely available to the community in general. Richard Wagner (Wagner, Richard), for example, suggested the need for a baritone double-reed instrument akin to the oboe; the resulting heckelphone has been featured in Richard Strauss (Strauss, Richard)'s opera Salome (1905) and subsequent works. Wagner also ordered a special type of tuba for use in his four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung, 1869–76). Not all modern changes in construction have been wholly advantageous, however. It is easier to play in tune on a modern woodwind instrument, but the older examples, being less cluttered with metal fittings, had a purer tone. Similarly, the modern horn is to most listeners inferior in tone quality to its 18th-century predecessor. Among Western orchestral instruments, only the trombone and the stringed instruments have remained, apart from minor modifications, unchanged in structure over the centuries (though the substitution of wire strings for gut has materially altered the tone of the violin). In contrast, the rate of technological change in electronic instruments has been almost bewilderingly fast.

Classification of instruments

Instruments have been classified in various ways, some of which overlap. The Chinese (arts, East Asian) divide them according to the material of which they are made—as, for example, stone, wood, silk, and metal. Writers in the Greco-Roman world distinguished three main types of instruments: wind, stringed, and percussion. This classification was retained in the Middle Ages and persisted for several centuries: it is the one preferred by some writers, with the addition of electronic instruments, at the present day. Some 16th-century writers excluded certain instruments from this classification; the musical theorist Lodovico Zacconi (Zacconi, Lodovico) went so far as to exclude all percussion instruments and established a fourfold division of his own—wind, keyed, bowed, and plucked.

Instruments have been classified in various ways, some of which overlap. The Chinese (arts, East Asian) divide them according to the material of which they are made—as, for example, stone, wood, silk, and metal. Writers in the Greco-Roman world distinguished three main types of instruments: wind, stringed, and percussion. This classification was retained in the Middle Ages and persisted for several centuries: it is the one preferred by some writers, with the addition of electronic instruments, at the present day. Some 16th-century writers excluded certain instruments from this classification; the musical theorist Lodovico Zacconi (Zacconi, Lodovico) went so far as to exclude all percussion instruments and established a fourfold division of his own—wind, keyed, bowed, and plucked. Classification and Examples of Some Musical InstrumentsA different fourfold classification was accepted by Hindus (Hinduism) at least as early as the 1st century BC: they recognized stringed instruments, wind instruments, percussion instruments of wood or metal, and percussion instruments with skin heads (i.e., drums). This ancient system—based on the material producing sound—was adopted by the Belgian instrument maker and acoustician Victor-Charles Mahillon (Mahillon, Victor-Charles), who named his four main classes autophones, or instruments made of a sonorous material that vibrates to produce sound (e.g., bells, rattles); membranophones (membranophone), in which a stretched skin is caused to vibrate (e.g., drums); aerophones (aerophone), in which the sound is produced by a vibrating column of air (wind instruments); and chordophones (chordophone), or stringed instruments. In their highly influential studies of musical instruments, the Austrian musicologist Erich von Hornbostel (Hornbostel, Erich Moritz von) and his German colleague Curt Sachs (Sachs, Curt) accepted and expanded Mahillon's basic division, creating the classification now used in most systematic studies of instruments. The name idiophones (idiophone) was substituted for autophones, and each class was subdivided according to a method similar to that used by botanists. A fifth class, electrophones (electrophone), in which vibration is produced by oscillating electric circuits, was added later. The Table (Classification and Examples of Some Musical Instruments) gives examples of instruments that fall within the various categories.

Many instruments can be played using more than one system of tone production and hence might reasonably appear in several subcategories. The double bass, for example, is usually considered a chordophone whose strings may be bowed or plucked; sometimes, however, the body of the instrument is slapped or struck, placing the double bass among the idiophones. The tambourine is a membranophone insofar as it has a skin head which is struck; but, if it is only shaken so that its jingles sound, it should be classed as an idiophone, for in this operation the skin head is irrelevant. Open flue stops are the foundation of organ tone, but the instrument also has a number of free reed stops, so that the organ belongs equally to the first and second order of aerophones. Modern composers not infrequently require players to treat their instruments in unorthodox ways, thus changing their position in the classification system.

It must be understood that the Sachs-Hornbostel system was created for the purpose of bringing order to the massive collections of musical instruments in ethnographic museums. It is directly analogous to the various book classification systems of libraries and, like them, is arbitrary. Musicians themselves generally think of instruments in terms of their technological features and playing method. To them, therefore, it is logical to group keyboard instruments together, ignoring the fact that in the Sachs-Hornbostel system such instruments fit into several categories.

It must be understood that the Sachs-Hornbostel system was created for the purpose of bringing order to the massive collections of musical instruments in ethnographic museums. It is directly analogous to the various book classification systems of libraries and, like them, is arbitrary. Musicians themselves generally think of instruments in terms of their technological features and playing method. To them, therefore, it is logical to group keyboard instruments together, ignoring the fact that in the Sachs-Hornbostel system such instruments fit into several categories.History and evolution

There has been speculation about the origin of instruments since antiquity. Older writers were generally content to rely on mythology or legends. In the 19th century, partly as a result of theories of evolution put forward by Charles Darwin (Darwin, Charles) and Herbert Spencer (Spencer, Herbert), new chronologies based on anthropological evidence were advanced. The British writer John Frederick Rowbotham argued that there was originally a drum stage, followed by a pipe stage, and finally a lyre stage. The Austrian writer Richard Wallaschek, on the other hand, maintained that, although rhythm was the primal element, the pipe came first, followed by song, and the drum last. Sachs based his chronology on archaeological excavation and the geographic distribution of the instruments found in them. Following this method, he established three main strata. The first stratum, which is found all over the world, consists of simple idiophones and aerophones; the second stratum, less widely distributed, adds drums and simple stringed instruments; the third, occurring only in certain areas, adds xylophones, drumsticks, and more complex flutes. In the 21st century, ethnomusicologists have questioned assumptions about the evolution of instruments from simple to complex; see above Technological developments (musical instrument).

The development of musical instruments among ancient high civilizations in Asia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean appears to have emphasized stringed instruments. In Central and South America, wind and struck instruments seem to have been most important. It is not always easy to say whether instruments are indigenous to a particular area, however, since their cultivation may well have spread from one country to another through trade or migration. Nevertheless, it is known that the harp was used from early times in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India and was imported into China after the end of the 4th century AD. In Greece it was regarded as a foreign instrument: the standard plucked instrument was the lyre, known in its fully developed form as the kithara (or cithara). Apart from the trumpet, the only wind instrument in normal use in Greece was the aulos, a double-reed instrument akin to the modern oboe. The Egyptians used wind instruments not only with double reeds but also with single reeds and thus may be said to have anticipated the clarinet. Peculiar to China was the sheng, or mouth organ; the Chinese also used as an artistic instrument the panpipes ( xiao), which in Greece had a recreational function.

The development of musical instruments among ancient high civilizations in Asia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean appears to have emphasized stringed instruments. In Central and South America, wind and struck instruments seem to have been most important. It is not always easy to say whether instruments are indigenous to a particular area, however, since their cultivation may well have spread from one country to another through trade or migration. Nevertheless, it is known that the harp was used from early times in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India and was imported into China after the end of the 4th century AD. In Greece it was regarded as a foreign instrument: the standard plucked instrument was the lyre, known in its fully developed form as the kithara (or cithara). Apart from the trumpet, the only wind instrument in normal use in Greece was the aulos, a double-reed instrument akin to the modern oboe. The Egyptians used wind instruments not only with double reeds but also with single reeds and thus may be said to have anticipated the clarinet. Peculiar to China was the sheng, or mouth organ; the Chinese also used as an artistic instrument the panpipes ( xiao), which in Greece had a recreational function.In medieval Europe, many instruments came from Asia, having been transmitted through Byzantium, Spain, or eastern Europe. Perhaps the most notable development in western Europe was the practice, originating apparently in the 15th century, of building instruments in families, from the smallest to the largest size. A typical family was that of the shawms (shawm), which were powerful double-reed instruments. A distinction was made between haut (loud) and bas (soft) instruments, the former being suitable for performance out-of-doors and the latter for more intimate occasions. Hence, the shawm came to be known as the hautbois (loud wood), and this name was transferred to its more delicately toned descendant, the 17th-century oboe. By the beginning of the 17th century the German musical writer and composer Michael Praetorius (Praetorius, Michael), in his Syntagma musicum (“Musical Treatise”), was able to give a detailed account of families of instruments of all kinds—recorders, flutes, shawms, trombones, viols, and violins.

Percussion instruments (percussion instrument)

Drum ensembles have achieved extraordinary sophistication in Africa, and the small hand-beaten drum is of great musical significance in western Asia and India. The native cultures of the Americas have always made extensive use of drums, as well as other struck and shaken instruments. In Southeast Asia and parts of Africa, xylophones and, since the introduction of metals, their cousins the metallophones play significant roles. Europe, however, has not placed great emphasis on drums and other percussion instruments. (See also percussion instrument.)

Drum ensembles have achieved extraordinary sophistication in Africa, and the small hand-beaten drum is of great musical significance in western Asia and India. The native cultures of the Americas have always made extensive use of drums, as well as other struck and shaken instruments. In Southeast Asia and parts of Africa, xylophones and, since the introduction of metals, their cousins the metallophones play significant roles. Europe, however, has not placed great emphasis on drums and other percussion instruments. (See also percussion instrument.)Stringed instruments (stringed instrument)

Many varieties of plucked instruments were found in Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance; but bowed instruments eventually came to characterize the area, and they played an important role in the rest of Eurasia and in North Africa as well. The idea of playing a stringed instrument with a bow may have originated with the horse cultures of Central Asia, perhaps in the 9th century AD. The technique then spread rapidly over most of the European landmass.

The European fiddle existed in various forms: by the 16th century these had settled down into two distinct types—the viol, known in Italy as viola da gamba (leg fiddle), and the violin, or viola da braccio (arm fiddle). The viol has a flat back, sloping shoulders, and six or seven strings; the violin has a rounded back, rounded shoulders, and four strings. The viol, unlike the violin, has frets—pieces of gut wound at intervals around the fingerboard—which make every stopped note (i.e., the string being pressed by the finger to produce a higher pitch) sound like an open (unstopped) string. The violin, being the smallest member of the family, came to be known by the diminutive violino: the tenor of the family was called simply viola, while the bass acquired the name violoncello, a diminutive of violone (“big fiddle”). (See also stringed instrument.)

The European fiddle existed in various forms: by the 16th century these had settled down into two distinct types—the viol, known in Italy as viola da gamba (leg fiddle), and the violin, or viola da braccio (arm fiddle). The viol has a flat back, sloping shoulders, and six or seven strings; the violin has a rounded back, rounded shoulders, and four strings. The viol, unlike the violin, has frets—pieces of gut wound at intervals around the fingerboard—which make every stopped note (i.e., the string being pressed by the finger to produce a higher pitch) sound like an open (unstopped) string. The violin, being the smallest member of the family, came to be known by the diminutive violino: the tenor of the family was called simply viola, while the bass acquired the name violoncello, a diminutive of violone (“big fiddle”). (See also stringed instrument.)Keyboard instruments (keyboard instrument)

Only in Europe did the keyboard develop—for reasons that are not clear. The principle of the keyboard has been used successfully to control bells (the carillon), plucked and struck stringed instruments (the piano and harpsichord), and wind instruments (the organ, the accordion, and the harmonium).

Of all instruments, the organ showed the most remarkable development from the early Middle Ages to the 17th century. Originally, sound was admitted to the pipes by withdrawing sliders or depressing levers. Both of these methods were clumsy: they gave way to a reduction in the size of the levers, which eventually could be depressed by the fingers, while the larger pipes were controlled by pedals. A further development was to separate the various rows of pipes, so that each row could be brought into action or suppressed by means of a draw stop. Once a manageable keyboard had been produced, it could be applied to the portable organ, carried by the player, which was already in use by the 12th century. Scientific experiments with the monochord, a stretched string that could be divided into various lengths by means of a metal tangent, were followed by the construction of an instrument with a whole range of strings and a keyboard similar to that of the organ—the clavichord. A similar adaptation of the plucking of stringed instruments led to the harpsichord, the ingenious mechanism of which had been perfected by the 16th century. It is curious that a similar method was not applied to the dulcimer, which was struck with hammers, until the early 18th century, when the Italian maker Bartolomeo Cristofori (Cristofori, Bartolomeo) constructed the first pianoforte (piano), so-called because, unlike the harpsichord, it could vary the tone from soft (piano) to loud (forte). (See also keyboard instrument.)

Of all instruments, the organ showed the most remarkable development from the early Middle Ages to the 17th century. Originally, sound was admitted to the pipes by withdrawing sliders or depressing levers. Both of these methods were clumsy: they gave way to a reduction in the size of the levers, which eventually could be depressed by the fingers, while the larger pipes were controlled by pedals. A further development was to separate the various rows of pipes, so that each row could be brought into action or suppressed by means of a draw stop. Once a manageable keyboard had been produced, it could be applied to the portable organ, carried by the player, which was already in use by the 12th century. Scientific experiments with the monochord, a stretched string that could be divided into various lengths by means of a metal tangent, were followed by the construction of an instrument with a whole range of strings and a keyboard similar to that of the organ—the clavichord. A similar adaptation of the plucking of stringed instruments led to the harpsichord, the ingenious mechanism of which had been perfected by the 16th century. It is curious that a similar method was not applied to the dulcimer, which was struck with hammers, until the early 18th century, when the Italian maker Bartolomeo Cristofori (Cristofori, Bartolomeo) constructed the first pianoforte (piano), so-called because, unlike the harpsichord, it could vary the tone from soft (piano) to loud (forte). (See also keyboard instrument.)Wind instruments (wind instrument)

In Europe the practice of constructing instruments in families continued from the 17th century onward. English composers wrote for the tenor hautbois, the intermediate oboe d'amore, and the bass, or baritone, oboe. The clarinet (the name means “little trumpet”) emerged at the end of the 17th century and, like the oboe, developed into a family extending to a contrabass clarinet in the 19th century and later a subcontrabass. It established itself only gradually in the orchestra in the course of the 18th century.

Trumpets and horns were used in most areas of Eurasia for ceremonial and military purposes. They remained relatively unchanged until the early 19th century, when valves were added to European instruments. This modification also led to the creation of new types. A pioneer in the field was the Belgian instrument maker Antoine-Joseph Sax (Sax, Antoine-Joseph), who in 1845 built a family of valved instruments called saxhorns (saxhorn), using the bugle as the basis for his invention. Similar instruments were widely adopted in military and brass bands, but only the bass, under the name bass tuba, became a normal member of the orchestra. Sax also invented the saxophone, a single-reed instrument like the clarinet but with a conical tube. This, too, was made in various sizes, which came to be used both in military bands and in jazz ensembles. The saxophone never became a normal member of the symphony orchestra, but the alto and the tenor have been used by art-music composers, largely as solo instruments, and occasionally a complete quartet of four different sizes has appeared in an orchestral work. (See also wind instrument.)

Trumpets and horns were used in most areas of Eurasia for ceremonial and military purposes. They remained relatively unchanged until the early 19th century, when valves were added to European instruments. This modification also led to the creation of new types. A pioneer in the field was the Belgian instrument maker Antoine-Joseph Sax (Sax, Antoine-Joseph), who in 1845 built a family of valved instruments called saxhorns (saxhorn), using the bugle as the basis for his invention. Similar instruments were widely adopted in military and brass bands, but only the bass, under the name bass tuba, became a normal member of the orchestra. Sax also invented the saxophone, a single-reed instrument like the clarinet but with a conical tube. This, too, was made in various sizes, which came to be used both in military bands and in jazz ensembles. The saxophone never became a normal member of the symphony orchestra, but the alto and the tenor have been used by art-music composers, largely as solo instruments, and occasionally a complete quartet of four different sizes has appeared in an orchestral work. (See also wind instrument.)Ensembles

The variety of musical ensembles used throughout the world is vast and beyond description, but the following principles apply nearly everywhere. Outdoor music, which is often ceremonial, most frequently involves the use of loud wind instruments and drums. Indoor music, which is more often intended for passive listening, emphasizes such quieter instruments as bowed and plucked strings and flutes.

The variety of musical ensembles used throughout the world is vast and beyond description, but the following principles apply nearly everywhere. Outdoor music, which is often ceremonial, most frequently involves the use of loud wind instruments and drums. Indoor music, which is more often intended for passive listening, emphasizes such quieter instruments as bowed and plucked strings and flutes.The establishment of orchestras (orchestra), as opposed to chamber groups, in the early 17th century led to a slight revision of these principles in Europe. The orchestra's sound is founded on a large ensemble of bowed strings, but it adds the previously outdoor instruments (wind and percussion) for colour and climax. As concert halls increased in size and popularity, so too did the sound-volume requirements of so-called indoor instruments. One result was that the violin family was favoured at the expense of the quieter viols. The latter, along with other instruments whose tone was too weak for orchestral music, gradually dropped out of use until the 20th century, when earlier styles of music and their associated instruments experienced a revival in popularity.

Automatic instruments

Water power, clockwork, steam, and electricity have all been used at various times to power musical instruments, enabling them to produce sound automatically. Examples include church bells, automatic organs, musical clocks, automatic pianos and harpsichords, music boxes, calliopes, and even automatic orchestras. Most of the impetus behind this phenomenon ceased with the development of the phonograph and other recording devices of the 20th century.

Water power, clockwork, steam, and electricity have all been used at various times to power musical instruments, enabling them to produce sound automatically. Examples include church bells, automatic organs, musical clocks, automatic pianos and harpsichords, music boxes, calliopes, and even automatic orchestras. Most of the impetus behind this phenomenon ceased with the development of the phonograph and other recording devices of the 20th century.Electric and electronic instruments (electronic instrument)

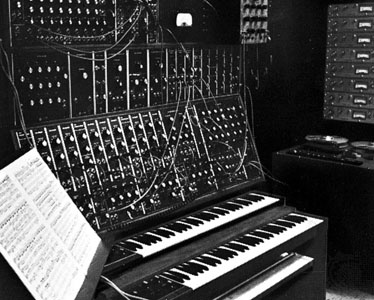

The development of electricity led not only to its use for mechanical purposes—for example, to control the key action and wind flow in the organ—but also as a means of amplification (e.g., in the vibraphone). With advances in electronics technology, players can now also make use of computers to generate and store tones and musical patterns. The growth of companies manufacturing electronic and digital instruments has been rapid, and the use of electronic equipment, such as sound synthesizers and recorders using analog or digital media, to produce and combine sound unrelated to the musical scale has become common.

The development of electricity led not only to its use for mechanical purposes—for example, to control the key action and wind flow in the organ—but also as a means of amplification (e.g., in the vibraphone). With advances in electronics technology, players can now also make use of computers to generate and store tones and musical patterns. The growth of companies manufacturing electronic and digital instruments has been rapid, and the use of electronic equipment, such as sound synthesizers and recorders using analog or digital media, to produce and combine sound unrelated to the musical scale has become common.Additional Reading

Comprehensive information on diverse musical instruments is found in such authoritative reference sources as Don Michael Randel, The New Harvard Dictionary of Music, 4th ed. (2003); New Oxford History of Music, 10 vol. (1954–90), with various reprints and reissues of individual volumes (1976–97); Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, 3 vol. (1984, reprinted 1997); Bruno Nettl et al. (eds.), The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, 10 vol. (1998–2002); Q. David Bowers, Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments (1972); and Richard Dobson, A Dictionary of Electronic and Computer Music Technology: Instruments, Terms, Techniques (1992).History and evolution of musical instruments are studied in many well-illustrated works, including J. Peter Burkholder, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca, A History of Western Music, 7th ed. (2006); Giovanni Comotti, Music in Greek and Roman Culture (1989; originally published in Italian, 1979); Thomas J. Mathiesen, Apollo's Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages (1999); David Munrow, Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance (1976); Sibyl Marcuse, A Survey of Musical Instruments (1975); Anthony Baines (ed.), Musical Instruments Through the Ages, new ed. (1976); Robert Donington, Music and Its Instruments (1982); Curt Sachs, The History of Musical Instruments (1940, reprinted 1968); and Jeremy Montagu, The World of Medieval and Renaissance Musical Instruments (1976), The World of Baroque and Classical Musical Instruments (1979), and The World of Romantic & Modern Musical Instruments (1981).Physical properties of the instruments are addressed in Reinhold Banek and Jon Scoville, Sound Designs: A Handbook of Musical Instrument Building (1980, reissued 1995); Charles Ford (ed.), Making Musical Instruments: Strings and Keyboard (1979); Dennis Waring, Folk Instruments (1979, reprinted as Making Folk Instruments in Wood, 1982, and as Making Wood Folk Instruments, 1990); and Neville H. Fletcher and Thomas D. Rosing, The Physics of Musical Instruments, 2nd ed. (1998, reissued 2005).Exhibitions and collections are the source of useful and well-illustrated information. A selection of catalogs includes Phillip T. Young, The Look of Music: Rare Musical Instruments, 1500–1900 (1980); Laurence Libin, American Musical Instruments in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1985); James M. Borders, European and American Wind and Percussion Instruments: Catalogue of the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments, University of Michigan (1988); Clifford Bevan, Musical Instrument Collections in the British Isles (1990); and James Coover, Musical Instrument Collections: Catalogues and Cognate Literature (1981).Geographic and ethnic distribution of musical instruments is explored in Nicholas Bessaraboff, Ancient European Musical Instruments (1941, reissued 1964); Emanuel Winternitz, Musical Instruments of the Western World (1967); Jaap Kunst, Music in Java, 3rd ed., rev. by E.L. Heins, 2 vol. (1973; originally published in Dutch, 1934); William P. Malm, Japanese Music and Musical Instruments (1959, reissued 1990), and Music Cultures of the Pacific, the Near East, and Asia, 2nd ed. (1977); S. Bandyopadhyaya, Musical Instruments of India (1980); Marie-Thérèse Brincard (ed.), Sounding Forms: African Musical Instruments (1989); Mary Remnant, Musical Instruments of the West (1978); and Emanuel Winternitz, Musical Instruments and Their Symbolism in Western Art (1967, reissued 1979).The process of arranging music for particular instruments and combinations of instruments is discussed in Howard Mayer Brown, Sixteenth-Century Instrumentation: The Music for the Florentine Intermedii (1973); Claude V. Palisca, Baroque Music, 3rd ed. (1991), surveying the seminal period in the development of concerted music; Adam Carse, The History of Orchestration (1925, reissued 1964); Hector Berlioz, Treatise on Instrumentation, rev. and enlarged by Richard Strauss (1948; originally published in French, 1844); Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow (Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov), Principles of Orchestration, trans. from Russian (1923, reissued 1964); Michael Hurd, The Orchestra (1980); Madeau Stewart, The Music Lover's Guide to the Instruments of the Orchestra (1980); Joan Peyser (ed.), The Orchestra: Origins and Transformations (1986); and Mark C. Gridley and David Cutler, Jazz Styles: History & Analysis, 8th ed. (2003).Current developments and research in the field are reflected in the articles of such special periodicals as The Galpin Society Journal (annual); Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society (annual); The Musical Quarterly; Early Music (quarterly); Ethno-musicology (3/yr.); and Asian Music (semiannual). Ed.

- everlasting

- Everlasting League

- Everleigh sisters

- Everly Brothers, the

- Evershed, John

- Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn

- tropism

- Tropites

- troposphere

- Troppau, Congress of

- Trossachs, the

- trot

- Trotskyism

- Trotsky, Leon

- Trotter, Wilfred

- Trotter, William Monroe

- trotting

- Trotzig, Birgitta

- troubadour

- Troubles, Council of

- Troubles, Time of

- trousers

- trout

- trout-perch

- Trouville