New Zealand

Introduction

MaoriAotearoa

New Zealand, flag of

an island nation in the South Pacific. New Zealand is a remote land. One of the last sizable territories suitable for habitation to be populated and settled, it lies more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) southeast of Australia, its nearest neighbour. The country comprises two main islands—the North and South islands—and a number of small islands, some of them hundreds of miles from the main group. The capital city is Wellington and largest urban area Auckland, both located on the North Island. New Zealand administers the South Pacific island group of Tokelau and claims a section of the Antarctic continent. Niue and the Cook Islands are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand.

an island nation in the South Pacific. New Zealand is a remote land. One of the last sizable territories suitable for habitation to be populated and settled, it lies more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) southeast of Australia, its nearest neighbour. The country comprises two main islands—the North and South islands—and a number of small islands, some of them hundreds of miles from the main group. The capital city is Wellington and largest urban area Auckland, both located on the North Island. New Zealand administers the South Pacific island group of Tokelau and claims a section of the Antarctic continent. Niue and the Cook Islands are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand.

an island nation in the South Pacific. New Zealand is a remote land. One of the last sizable territories suitable for habitation to be populated and settled, it lies more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) southeast of Australia, its nearest neighbour. The country comprises two main islands—the North and South islands—and a number of small islands, some of them hundreds of miles from the main group. The capital city is Wellington and largest urban area Auckland, both located on the North Island. New Zealand administers the South Pacific island group of Tokelau and claims a section of the Antarctic continent. Niue and the Cook Islands are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand.

an island nation in the South Pacific. New Zealand is a remote land. One of the last sizable territories suitable for habitation to be populated and settled, it lies more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) southeast of Australia, its nearest neighbour. The country comprises two main islands—the North and South islands—and a number of small islands, some of them hundreds of miles from the main group. The capital city is Wellington and largest urban area Auckland, both located on the North Island. New Zealand administers the South Pacific island group of Tokelau and claims a section of the Antarctic continent. Niue and the Cook Islands are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand.New Zealand was the largest country in Polynesia when it was annexed by the British in 1840. Thereafter it was, successively, a crown colony, a self-governing colony (1856), and a dominion (1907). By the 1920s it controlled almost all of its internal and external policies, although it did not become fully independent until 1947, when it adopted the Statute of Westminster. It is a member of the Commonwealth of former British dependencies.

New Zealand is a land of great contrasts and diversity. Active volcanoes, spectacular caves, deep glacier lakes, verdant valleys, dazzling fjords, long sandy beaches, and the spectacular snow-capped peaks of the Southern Alps—all contribute to New Zealand's scenic beauty. New Zealand also boasts a unique array of vegetation and animal life, much of it developing during the country's prolonged isolation. It is the sole home, for example, of the long-beaked, flightless kiwi, the ubiquitous nickname for New Zealanders.

Perhaps the most famous New Zealander is Sir Edmund Hillary (Hillary, Sir Edmund), whose ascent of Mount Everest with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay in 1953 was one of the defining moments of the 20th century. “In some ways,” Hillary suggested, “I epitomise the average New Zealander: I have modest abilities, I combine these with a good deal of determination, and I rather like to succeed.”

Perhaps the most famous New Zealander is Sir Edmund Hillary (Hillary, Sir Edmund), whose ascent of Mount Everest with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay in 1953 was one of the defining moments of the 20th century. “In some ways,” Hillary suggested, “I epitomise the average New Zealander: I have modest abilities, I combine these with a good deal of determination, and I rather like to succeed.”Despite New Zealand's isolation, the country has been fully engaged in international affairs since the early 20th century, being an active member of both the League of Nations and the United Nations. It has also participated in several wars, including World Wars I and II. Economically, the country was dependent on the export of agricultural products, especially to Great Britain. The entry of Britain into the European Community in the early 1970s, however, forced New Zealand to expand its trade relations with other countries. It also has begun to develop a much more extensive and varied industrial sector. Tourism has played an increasingly important role in the economy, though this sector was hit hard by the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s.

The social and cultural gap between New Zealand's two main groups—the indigenous Maori of Polynesian heritage and colonizers and later immigrants from the British Isles and their descendants—has decreased since the 1970s, though educational and economic differences between the two groups remain. Immigration from other areas—Asia, Africa, and eastern Europe—has also left its mark, and New Zealand culture today reflects these many influences. Minority rights and race-related issues continue to play an important role in New Zealand politics.

Land (New Zealand)

New Zealand is about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) long (north-south) and about 280 miles (450 km) across at its widest point. The country is slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Colorado and a little larger than the United Kingdom. About two-thirds of the land is economically useful, the remainder being mountainous. Because of its numerous harbours and fjords, the country has an extremely long coastline relative to its area.

Relief

Although New Zealand is small, its geological history is complex. Land has existed in the vicinity of New Zealand for most of the last 500 million years. The earliest known rocks originated as sedimentary deposits of late Precambrian or early Cambrian age (i.e., about 534 million years old); their source area was probably the continental forelands of Australia and Antarctica, then part of a nearby single supercontinent. Continental drift (the movement of large plates of the Earth's crust) created a distinct island arc and oceanic trench structure by Carboniferous time (354 million to 290 million years ago), when deposition began in the downwarps (trenches) of the sedimentary rocks that today make up some three-fourths of New Zealand. This environment lasted about 250 million years and is typified by both downwarped oceanic sedimentary rocks and by terrestrial volcanic rocks. This period was terminated in the west at the beginning of the Cretaceous Period (about 144 million years ago) by the Rangitata Orogeny (mountain-building episode), although downwarp deposition continued in the east. These mountains were slowly worn down by erosion, and the sea transgressed, eventually covering almost all of the land. At the end of Oligocene time (about 23.8 million years ago) the Kaikoura Orogeny began, raising land above the sea again, including the Southern Alps of the South Island. Many of the great earth movements associated with this final orogeny took place (and take place today) along faults, which divide the landscape into great blocks, chief of which is the Alpine Fault of the South Island. The erosion and continued movement of these faulted blocks, together with the continuing volcanism of the North Island, define to a large extent the landscape of the country.

Although New Zealand is small, its geological history is complex. Land has existed in the vicinity of New Zealand for most of the last 500 million years. The earliest known rocks originated as sedimentary deposits of late Precambrian or early Cambrian age (i.e., about 534 million years old); their source area was probably the continental forelands of Australia and Antarctica, then part of a nearby single supercontinent. Continental drift (the movement of large plates of the Earth's crust) created a distinct island arc and oceanic trench structure by Carboniferous time (354 million to 290 million years ago), when deposition began in the downwarps (trenches) of the sedimentary rocks that today make up some three-fourths of New Zealand. This environment lasted about 250 million years and is typified by both downwarped oceanic sedimentary rocks and by terrestrial volcanic rocks. This period was terminated in the west at the beginning of the Cretaceous Period (about 144 million years ago) by the Rangitata Orogeny (mountain-building episode), although downwarp deposition continued in the east. These mountains were slowly worn down by erosion, and the sea transgressed, eventually covering almost all of the land. At the end of Oligocene time (about 23.8 million years ago) the Kaikoura Orogeny began, raising land above the sea again, including the Southern Alps of the South Island. Many of the great earth movements associated with this final orogeny took place (and take place today) along faults, which divide the landscape into great blocks, chief of which is the Alpine Fault of the South Island. The erosion and continued movement of these faulted blocks, together with the continuing volcanism of the North Island, define to a large extent the landscape of the country.Both the North and South (South Island) islands are roughly bisected by mountains. Swift, snow-fed rivers drain from the hills, although only in the east of the South Island have extensive alluvial plains been built up. The alluvial Canterbury Plains contrast sharply with the precipitous slopes and narrow coastal strip of the Westland region on the west coast of the South Island. The Southern Alps are a 300-mile- (480-km-) long chain of fold mountains containing New Zealand's highest mountain—Mount Cook (Cook, Mount) (in Maori, Aoraki, also spelled Aorangi, meaning “cloud piercer”) at 12,316 feet (3,754 metres)—and some 20 other peaks that rise above 10,000 feet (3,000 metres), as well as an extensive glacier system with associated lakes.

There are more than 360 glaciers in the Southern Alps. The Tasman Glacier, the largest in New Zealand, with a length of 18 miles (29 km) and a width of more than one-half mile (2.5 km), flows down the eastern slopes of Mount Cook. Other important glaciers on the eastern slopes of the Southern Alps are the Murchison, Mueller, and Godley; Fox and Franz Josef are the largest on the western slopes. The North Island has seven small glaciers on the slopes of Mount Ruapehu.

There are more than 360 glaciers in the Southern Alps. The Tasman Glacier, the largest in New Zealand, with a length of 18 miles (29 km) and a width of more than one-half mile (2.5 km), flows down the eastern slopes of Mount Cook. Other important glaciers on the eastern slopes of the Southern Alps are the Murchison, Mueller, and Godley; Fox and Franz Josef are the largest on the western slopes. The North Island has seven small glaciers on the slopes of Mount Ruapehu. In the north of the South Island the Alps break up into steep upswelling ridges. On their western face there are mineral deposits, and to the east they continue into two parallel ranges, terminating in a series of sounds. To the south the Alps break up into rugged, dissected country of difficult access and magnificent scenery, particularly toward the western tip of the island (called Fiordland). On its eastern boundary this wilderness borders a high central plateau called Central Otago, which has an almost continental climate.

In the north of the South Island the Alps break up into steep upswelling ridges. On their western face there are mineral deposits, and to the east they continue into two parallel ranges, terminating in a series of sounds. To the south the Alps break up into rugged, dissected country of difficult access and magnificent scenery, particularly toward the western tip of the island (called Fiordland). On its eastern boundary this wilderness borders a high central plateau called Central Otago, which has an almost continental climate. The terrain of the North Island is much less precipitous than that of the South and has a more benign climate and greater economic potential. In the centre of the island the Volcanic Plateau rises abruptly from the southern shores of New Zealand's largest natural lake, Taupo (Taupo, Lake), itself an ancient volcanic crater. To the east ranges form a backdrop to rolling country in which pockets of great fertility are associated with the river systems. To the south more ranges run to the sea. On the western and eastern slopes of these ranges the land is generally poor, although the western downland region is fertile until it fades into a coastal plain dominated by sand dunes. To the west of the Volcanic Plateau fairly mountainous country merges into the undulating farmlands of the Taranaki (Taranaki, Mount) region, where the mild climate favours dairy farming even on the slopes of Mount Taranaki (Taranaki, Mount) (Egmont), a volcano that has been dormant since the 17th century. North of Mount Taranaki are the spectacular Waitomo caves, where stalactites and stalagmites are illuminated by thousands of glowworms.

The terrain of the North Island is much less precipitous than that of the South and has a more benign climate and greater economic potential. In the centre of the island the Volcanic Plateau rises abruptly from the southern shores of New Zealand's largest natural lake, Taupo (Taupo, Lake), itself an ancient volcanic crater. To the east ranges form a backdrop to rolling country in which pockets of great fertility are associated with the river systems. To the south more ranges run to the sea. On the western and eastern slopes of these ranges the land is generally poor, although the western downland region is fertile until it fades into a coastal plain dominated by sand dunes. To the west of the Volcanic Plateau fairly mountainous country merges into the undulating farmlands of the Taranaki (Taranaki, Mount) region, where the mild climate favours dairy farming even on the slopes of Mount Taranaki (Taranaki, Mount) (Egmont), a volcano that has been dormant since the 17th century. North of Mount Taranaki are the spectacular Waitomo caves, where stalactites and stalagmites are illuminated by thousands of glowworms.The northern shores of Lake Taupo bound a large area of high economic activity, including forestry. Even farther north there are river terraces sufficiently fertile for widespread dairy and mixed farming. The hub of this area is Auckland, which is situated astride an isthmus with a deep harbour on the east and a shallow harbour to the west. The region north of Auckland, called Northland, becomes gradually subtropical in character, marked generally by numerous deep-encroaching inlets of the sea bordered by mangrove swamps.

Drainage

The mountainous country of both islands is cut by many rivers, which are swift, unnavigable, and a barrier to communication. The longest is the Waikato (Waikato River), in the North Island, and the swiftest, the Clutha (Clutha River), in the South. Many of the rivers arise from or drain into one or other of the numerous lakes associated with the mountain chains. A number of these lakes have been used as reservoirs for hydroelectric projects, and artificial lakes, including Lake Benmore, New Zealand's largest, have been created for hydroelectric power generation.

Soils

New Zealand's soils are often deeply weathered, lacking in many nutrients, and, most of all, highly variable over short distances. Soils based on sedimentary rock formations are mostly clays and are found over about three-fourths of the country. Pockets of fertile alluvial soil in river basins or along river terraces form the orchard and market-gardening regions of the country.

In the South Island, variations in mean annual precipitation have had an important effect. The brown-gray soils of Central Otago are thin and coarse-textured and have subsoil accumulations of lime, whereas the yellow-gray earths of much of the Canterbury Plains, as well as areas of lower rainfall in the North Island, are partially podzolized (layered) with a gray upper horizon. The yellow-brown soils that characterize much of the North Island are often podzolized from acid leaching in humid forest environments. Their fertility varies with the species composition of their vegetation. Forests of false beech (Nothofagus), as well as of tawa and taraire, indicate soils of reasonably high fertility, while forests of kauri pine and rimu indicate podzolized soils.

Climate

New Zealand's climate is determined by its latitude, its isolation, and its physical characteristics. There are no extremes of temperature.

A procession of high-pressure systems (anticyclones) separated by middle-latitude cyclones and fronts crosses New Zealand from west to east. Characteristic is the sequence of a few days of fine weather and clear skies separated by days with unsettled weather and often heavy rain. In summer subtropical highs are dominant, bringing protracted spells of fine weather and intense sunshine. In winter middle-latitude lows and active fronts increase the blustery wet conditions, although short spells of clear skies also occur. Because of the high mountain chains that lie across the path of the prevailing winds, the contrast in climate from west to east is sharper than that from north to south. Mountain ranges are also responsible for the semicontinental climate of Central Otago.

Changes in elevation make for an intricate pattern of temperature variations, especially on South Island, but some generalizations for conditions at sea level can be made. The average seasonal and diurnal temperature range is about 18 °F (10 °C). Variation in mean monthly temperature from north to south is about 10 °F (6 °C). In most parts of the country daytime highs in summer are above 70 °F (21 °C), occasionally exceeding 81 °F (27 °C) in the north, while in winter daytime highs throughout the country are rarely below 50 °F (10 °C).

Precipitation is highest in areas dominated by mountains exposed to the prevailing westerly and northwesterly winds. Although mean annual rainfall ranges from an arid 12 inches (300 mm) in Central Otago to as much as 315 inches (800 cm) in the Southern Alps, for the whole country it is typical of temperate zone countries—25–60 inches (64–152 cm), usually spread reliably throughout the year. Snow is common only in mountainous regions, but frost is frequent in inland valleys in winter. Humidity ranges from 70 to 80 percent on the coast, generally being 10 percent lower inland. In the lee of the Southern Alps, where the effect of the foehn (a warm, dry wind of leeward mountain slopes) is marked, humidity can become very low.

Plant and animal life

The indigenous vegetation of New Zealand consisted of mixed evergreen forest covering perhaps two-thirds of the total land area. The islands' prolonged isolation has encouraged the development of species unknown to the rest of the world; almost 90 percent of the indigenous plants are peculiar to the country. Today, dense “bush” survives only in areas unsuitable for settlement and in parks and reserves. On the west coast of the South Island this mixed forest still yields most of the native timber used by industry. Along the mountain chain running the length of the country, the false beech is the predominant forest tree.

European settlement made such inroads on the natural forest that erosion in high-country areas became a serious problem. The State Forest Service was established to repair the damage and uses forest-management techniques and reforestation with exotic trees. Experimental areas on the Volcanic Plateau were planted with radiata pine, an introduction from California. This conifer has adapted to New Zealand conditions so well that it is now the staple plantation tree, growing to maturity in 25 years and having a high rate of natural regeneration. Large areas of the Volcanic Plateau, together with other marginal or subagricultural land north of Auckland and near Nelson, are now planted with this species.

European broad-leaved species are widely used ornamentally, and willows and poplars are frequently planted to help prevent erosion on hillsides. Gorse has acclimatized so readily that it has become a menace, spreading over good and bad land alike, its only virtue being as a nursery for regenerating bush.

Because of New Zealand's isolation, there were no higher animal life forms in the country when the Maori arrived in the late 13th or early 14th century AD. There were three kinds of reptiles—the skink, the gecko, and the tuatara, a “beak-headed” reptile extinct elsewhere for 100 million years—and also a few primitive species of frogs and two species of bats. These are all extant, although confined to outlying islands and isolated parts of the country.

In addition to their domestic animals, Europeans also brought other species with them. Red deer, introduced for sport, and the Australian opossums (for skins) have multiplied beyond imagination and have done untold damage to the vegetation of the high-country bush. The control of goats, deer, opossums, and rabbits—even in the national parks—is a continuing problem.

In the absence of predatory animals, New Zealand is a paradise for birds, the most interesting of which are flightless. The moa was a large bird, eventually exterminated by the Maori. The kiwi, another flightless species, is extant, though only in secluded bush areas. The weka and the notornis, or takahe (barely rescued from extinction), probably became flightless after arrival. The pukeko, a swamp hen relative of the weka, is even now in the process of losing the use of its wings. Some birds, such as saddlebacks and native thrushes (thought to be extinct), are peculiar to New Zealand, but many others (e.g., tuis, fantails, and bellbirds) are closely related to Australian birds. Birds that breed in or near New Zealand include the Australian (Australasian) gannets, skuas, penguins, shags, and royal albatrosses.

In the absence of predatory animals, New Zealand is a paradise for birds, the most interesting of which are flightless. The moa was a large bird, eventually exterminated by the Maori. The kiwi, another flightless species, is extant, though only in secluded bush areas. The weka and the notornis, or takahe (barely rescued from extinction), probably became flightless after arrival. The pukeko, a swamp hen relative of the weka, is even now in the process of losing the use of its wings. Some birds, such as saddlebacks and native thrushes (thought to be extinct), are peculiar to New Zealand, but many others (e.g., tuis, fantails, and bellbirds) are closely related to Australian birds. Birds that breed in or near New Zealand include the Australian (Australasian) gannets, skuas, penguins, shags, and royal albatrosses.Because New Zealand lies at the meeting place of warm and cool ocean currents, a great variety of fish is found in its surrounding waters. Tropical species such as tuna, marlin, and some sharks are attracted by the warm currents, which are locally populated by snapper, trevally, and kahawai. The Antarctic cold currents, on the other hand, bring blue and red cod and hakes, while some fish—tarakihi, grouper, and bass—which can tolerate a considerable range of water temperatures, are found off the entire coastlines. Flounder and sole abound on tidal mudflats, and crayfish are prolific in rocky areas off the coastline.

People (New Zealand)

Ethnic groups

New Zealand was one of the last sizable land areas suitable for habitation to be populated by human beings. The first settlers were Polynesians (Polynesian culture) who came from somewhere in eastern Polynesia, possibly from what is now French Polynesia. They remained isolated in New Zealand until the arrival of European explorers, the first of whom was the Dutchman Abel Janszoon Tasman (Tasman, Abel Janszoon) in 1642. During that time they grew in numbers to between 100,000 and 200,000, living almost exclusively on North Island. They had no name for themselves but eventually adopted the name Maori (meaning “Normal”) to distinguish themselves from the Europeans, who, after the voyages of the Englishman Captain James Cook (Cook, James) (1769–77), began to come with greater frequency.

The Europeans brought with them an array of diseases to which the Maori had no resistance, and the Maori population declined rapidly. Their reduction in numbers was exacerbated by widespread intertribal warfare (once the Maori had acquired firearms) and by warfare with Europeans. By 1896 only about 42,000 Maori remained. Early in the 20th century, however, their numbers began to increase as they acquired resistance to such diseases as measles and influenza and as their birth rate subsequently recovered. In 2000 there were some 380,000 Maoris in New Zealand.

Europeans had begun to settle in New Zealand in the 1820s; they arrived in increasing numbers after the country was annexed by Great Britain following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (Waitangi, Treaty of) in 1840. By the late 1850s settlers outnumbered Maori, and in 1900 there were some 772,000 Europeans, most of whom by then were New Zealand-born. Although the overwhelming majority of immigrants were of British extraction, other Europeans came as well, notably from Scandinavia, Germany, Greece, Italy, and the Balkans. Groups of central Europeans came between World Wars I and II, and a large body of Dutch immigrants arrived after World War II. Asians coming to New Zealand have included Chinese and Indians and more recently a growing community of Pacific Islanders from Samoa (formerly Western Samoa), the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau.

Contemporary New Zealand thus has a great majority of people of European origin, a significant minority of Maori, and smaller numbers of Pacific Islanders, Chinese, and Indians. This diverse society has produced some racial tensions, but they have been minor compared with those in other parts of the world. Although the Maori have legal equality with those of European descent (called pakeha by the Maori), many feel unable to take their full place in a European-type society without compromising their traditional values.

Languages

New Zealand is predominantly an English-speaking country, though both English and Maori are official languages. Virtually all Maori speak English, and about one-third of them also speak Maori. The Maori language is taught at a number of schools. The only other non-English language spoken by any significant number of people is Samoan.

Religion

New Zealand is nominally Christian, about half of the population adhering to the Anglican, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, and Methodist denominations; of these, Anglicans make up the largest religious group in New Zealand. Other Protestant sects, the Eastern Orthodox churches, Jewish congregations, and Maori adaptations of Christianity (the Ratana and Ringatu churches) account for nearly all of the rest, although nearly one-fourth of the population does not claim any religious affiliation. There is no established (official) religion, but Anglican cathedrals are generally used for state occasions.

Settlement patterns

Because New Zealand is small and the population is relatively homogeneous, there are no sharply differentiated social or political regions. The North, however, is popularly regarded as being more enterprising, while the South (South Island) is traditionally regarded as being conservative. While the west coast is romantically nostalgic for its rollicking gold-rush days, the east coast conjures up the picture of sheep barons on their extensive ranches (called stations).

Because New Zealand is small and the population is relatively homogeneous, there are no sharply differentiated social or political regions. The North, however, is popularly regarded as being more enterprising, while the South (South Island) is traditionally regarded as being conservative. While the west coast is romantically nostalgic for its rollicking gold-rush days, the east coast conjures up the picture of sheep barons on their extensive ranches (called stations).The New Zealand countryside is thinly populated, but there are many small towns with populations of up to 10,000 and a number of provincial cities of more than 20,000. The smallest towns and villages are becoming deserted as people drift to the bigger towns and cities.

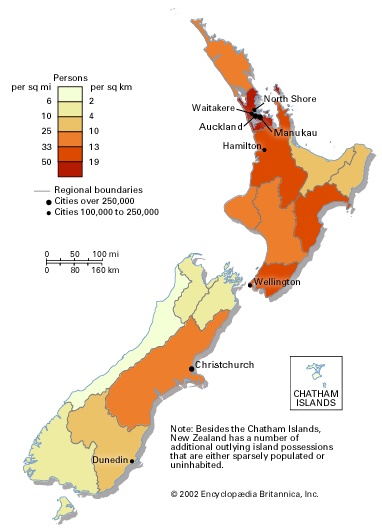

The main urban areas are Auckland, the centre of the North and the main industrial complex; Hamilton, in the middle of the North Island; Wellington, centrally located at the southern tip of North Island and the political and commercial capital; Christchurch, in the middle of the South Island and the second largest industrial area; and finally, still farther south, Dunedin. Although New Zealand is notable for the strength of its rural sector, the great majority of people live in cities, and urban concentration is proceeding apace. There is also a marked difference in the degree of population growth of the two main islands—the North having about three-fourths of the total population, in sharp contrast to the earlier years of systematic settlement. As in the past, the great majority of Maori live on the North Island; since World War II, however, most Maori have become urban dwellers, as have the Pacific Islanders.

The main urban areas are Auckland, the centre of the North and the main industrial complex; Hamilton, in the middle of the North Island; Wellington, centrally located at the southern tip of North Island and the political and commercial capital; Christchurch, in the middle of the South Island and the second largest industrial area; and finally, still farther south, Dunedin. Although New Zealand is notable for the strength of its rural sector, the great majority of people live in cities, and urban concentration is proceeding apace. There is also a marked difference in the degree of population growth of the two main islands—the North having about three-fourths of the total population, in sharp contrast to the earlier years of systematic settlement. As in the past, the great majority of Maori live on the North Island; since World War II, however, most Maori have become urban dwellers, as have the Pacific Islanders.Demographic trends

Life expectancy in New Zealand is high, with males living on average almost 76 years and females 81 years. The death rate is below the world average, and the major causes of death are diseases of the circulatory or respiratory system and cancer. Population growth has been slow: less than 1 percent per year. The natural rate of increase has been highest for the Pacific Islanders and for the Maori, both groups having a more youthful population.

Since World War II New Zealand has generally had an annual excess of arrivals over departures, a major contributor to overall population growth, and this has led to frequent debates about limiting immigration. Although in the past most immigrants came from Great Britain and The Netherlands, they have been surpassed by Pacific Islanders and Asians. Australia is the preferred destination of emigrators. Both immigration and emigration are sensitive to the rate of growth of the New Zealand economy and its employment opportunities, as well as to conditions overseas.

Economy

New Zealand has a small, developing economy in comparison with other Commonwealth countries. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries New Zealand's standard of living was one of the highest in the world, but since World War II the rate of growth has been one of the slowest among the developed countries. The main causes of this retardation have been the slow growth of the economy of the United Kingdom (which formerly was the main destination of New Zealand's exports) and the high tariffs imposed by the major industrial nations against the country's agricultural products (e.g., butter and meat), though the latter has improved following the 1994 ratification of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. New Zealand's economic history since the mid 20th century has consisted largely of the attempt to evade these protectionist constraints by diversifying its farm economy and by expanding its manufacturing base. This has been achieved partly by large-scale government intervention and partly by the natural working of market forces.

New Zealand has had a long history of government intervention in the economy, ranging from state institutions competing in banking and insurance to an extensive social security system. Until the early 1980s most administrations strengthened and supported this paternalism or state socialism, but since then government policy has generally shifted away from intervention, although no move has been made to dismantle the basic elements of social security. Some of the subsidies and tax incentives to agricultural and manufacturing exporters have been abolished, and such government enterprises as the Post Office have become more commercially oriented and less dependent on government subsidies. In addition, the government has attempted to resolve the difficult issue of restrictive practices in the labour market, such as limits on the entry into some occupations.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

New Zealand's farming base required a relatively complex economy. Highly productive pastoral farming, embracing extensive sheep grazing and large-scale milk production, was made possible by a temperate climate, heavy investment in land improvement (including the introduction of European grasses and regular application of imported fertilizers), and highly skilled farm management by owner-occupiers, who used one of the highest ratios of capital to labour in farming anywhere in the world. The farms supported and required many specialized services: finance, trade, transport, building and construction, and especially the processing of butter, cheese, and frozen lamb carcasses and their by-products. This economy could be described as an offshore European farm, which exported wool and processed dairy products and imported a variety of finished manufactured consumer and capital goods, raw materials, and petroleum. Since the 1960s there has been a proportionate decline in pastoral farming in relation to growth in forestry (and the production of paper and other wood products), horticulture, fishing, and deer farming, as well as manufacturing. Winemaking has also flourished since the 1960s, and today many New Zealand wines rank among the world's best.

New Zealand's farming base required a relatively complex economy. Highly productive pastoral farming, embracing extensive sheep grazing and large-scale milk production, was made possible by a temperate climate, heavy investment in land improvement (including the introduction of European grasses and regular application of imported fertilizers), and highly skilled farm management by owner-occupiers, who used one of the highest ratios of capital to labour in farming anywhere in the world. The farms supported and required many specialized services: finance, trade, transport, building and construction, and especially the processing of butter, cheese, and frozen lamb carcasses and their by-products. This economy could be described as an offshore European farm, which exported wool and processed dairy products and imported a variety of finished manufactured consumer and capital goods, raw materials, and petroleum. Since the 1960s there has been a proportionate decline in pastoral farming in relation to growth in forestry (and the production of paper and other wood products), horticulture, fishing, and deer farming, as well as manufacturing. Winemaking has also flourished since the 1960s, and today many New Zealand wines rank among the world's best.Apart from gold's brief heyday, biological resources have always been more significant than minerals. Domestic animals introduced from Europe have thrived in New Zealand. Forestry has always been important, but the emphasis has swung from felling the original forest for timber to afforestation with pine trees for both timber and pulp.

Resources and power

Most minerals, metallic and nonmetallic, occur in New Zealand, but few are found in sufficient quantities for commercial exploitation. The exceptions are gold, which in the early years of organized settlement was a major export; coal, which is still mined to a considerable extent; iron sands, which are exploited both for export and for domestic use; and, most recently, natural gas. In addition, construction materials, with which the country is well endowed, are quarried.

The country has exploited its great hydroelectric potential to such an extent that hydroelectricity supplies some two-thirds of the country's power. A notable feature of the New Zealand electricity grid is the direct-current cable linking the two main islands, enabling the South's surplus hydroelectric power to be used by the North's concentration of industry and people. Since the early 1970s geothermal and coal- and gas-fired stations have also been constructed. In addition, partnerships between government and private interests have developed natural-gas reserves and constructed the world's first plant producing gasoline from natural gas.

Manufacturing

Even in the 19th century New Zealand's relative geographic isolation made necessary a proportionately large industrial labour force engaged in the manufacture and repair of agricultural machinery and in shipbuilding, brewing, and timber processing. After the 1880s the factory processing of farm products swelled these numbers, while the temporary isolation of World Wars I and II stimulated the production of a wide range of manufactured goods that previously had been imported. Protectionist policies first espoused, although weakly, by governments in the late 19th century were strengthened after World War I. From the end of World War II until the early 1970s manufacturing industries were protected by import licensing fees in order to maintain full employment. Thus, there developed some labour-intensive, heavily protected, and uneconomic activities—such as automobile and consumer-electronics assembly (with the manufacture of some parts and components)—that have not been able to remain competitive.

Finance

Banking was established early in New Zealand. By the early 1970s an oligopolistic structure had emerged, consisting of several large trading banks (the largest being state-owned and the others foreign-owned), presided over by a central bank—the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (which issues the country's national currency, the New Zealand dollar)—and supplemented by other types of specialty institutions. Since the early 1980s the financial industry has been transformed, as the trading banks have lost their privileged position and the government has removed controls over financial institutions. The capital market has become highly competitive, with new, often foreign-owned specialty institutions emerging. In addition, in early 1985 transactions in foreign exchange were freed, and for the first time the exchange rate was floated in a competitive market.

Trade

There has been a related change in the composition of exports, although meat and dairy products have continued to predominate; wood and wood products are also significant. The major imports are machinery and transport equipment. Since the importance of trade with Great Britain has been reduced, that with Japan, the United States, and East Asian countries has grown. Trade with Australia has always been significant. A succession of trade agreements (1933, 1965, 1977) provided the basis of the Australia and New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (known as CER), signed in 1983. This agreement eventually eliminated duties and commodity quotas between the two countries and was seen by some as the first step toward integrating their economies. In 1995 the CER joined with the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Free Trade Area (AFTA) to promote trade and investment between the two areas.

Services

Tourism has become an important part of the country's economy. Most of the country's visitors originate from Australia, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Following the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, New Zealand's tourism suffered a major decline, but it was recovering by the early 21st century.

Labour and taxation

The labour force has long been organized into strong trade unions. Like Australia, New Zealand evolved a system of compulsory arbitration in which the government played a major role. Beginning in the late 1960s, however, government policy generally alternated between periods of government-imposed freezes on wages and prices and periods of officially tolerated bargaining between unions and employers, although the strong link between the labour markets of New Zealand and Australia—especially in the skilled trades and professional vocations—was a major constraint on establishing a set policy. However, with the passage of the Employment Contracts Act (1991), which ended compulsory union membership, the number of union members has fallen dramatically—more than half in the first five years the act was in force.

Although taxation in New Zealand in relation to national income is not particularly high in comparison to other developed countries, direct taxation (taxation of personal income) has traditionally been relied upon to an unusual extent. The introduction in 1986 of a value-added tax on goods and services thus represented a fiscal revolution, because it was linked to a reduction in income tax rates and to an increase in government transfer payments to low-income families.

Transportation and telecommunications

In spite of the rugged nature of the country, most of the inhabited areas of New Zealand are readily accessible; the road system is good even in rural districts, and modern freeways have been built around the main cities. Though the difficult country makes for slow journeys, the distances involved are seldom great.

The railway network, owned and operated by Tranz Rail Limited, is independent of direct government control. It comprises a main trunk line spanning both islands via roll-on ferries and branch lines linking most towns. Narrow tunnels limit track gauges, which until the late 20th century precluded the introduction of express trains. Rail travel is notoriously slow, discouraging passenger travel, but service is efficient for large-scale movement of goods over considerable distances. Long-standing regulations protecting the railways against competition by road carriers were abolished in the early 1980s, and as a consequence long-distance road cartage has increased.

The difficult terrain has greatly encouraged air travel in New Zealand; most provincial towns have airports, and all major urban centres are linked by air service. The main internal airline, Air New Zealand (Air New Zealand Limited), is a public corporation; it faces increasing competition from private operators. Air New Zealand, along with several foreign airlines, handles the country's international service, with international air terminals at Auckland, Christchurch, and Wellington. Hamilton, Palmerston North, Queenstown, and Dunedin also offer limited international service.

New Zealand's telecommunications industry underwent numerous reforms in the late 20th century to transform the country into one of the leaders in the field. The country's Post Office originally had a monopoly on telecommunication services, but it was plagued by economic difficulties and poor service. The state-run Telecom Corporation of New Zealand was formed in 1987 (privatized in 1990), and industry deregulation began in 1989. The creation of numerous telecommunication companies and the influx of foreign investments resulted in great technological improvements and competitive prices. By the late 20th century nearly one-tenth of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) was spent on telecommunications, a rate that was one of the highest in the world. Nearly half of the country's population has access to the Internet.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

New Zealand has a parliamentary form of government based on the British model. Legislative power is vested in the single-chamber House of Representatives (Parliament), the members of which are elected for three-year terms. There are two dominant parties, National and Labour; the party that commands a majority in the House forms the government. The leader of the governing party becomes the prime minister, who, with ministers responsible for different aspects of government, forms a cabinet. The cabinet is the central organ of executive power. Most legislation is initiated in the House on the basis of decisions made by the cabinet; Parliament must then pass it by a majority vote before it can become law. The cabinet, however, has extensive regulatory powers that are subject to only limited parliamentary review. Because cabinet ministers sit in the House and because party discipline is invariably strong, legislative and executive authority are effectively fused.

The British monarch is the formal head of state and is represented technically by a governor-general appointed by the monarch (with the recommendation of the New Zealand government) to a five-year term. The governor-general has only limited authority, but the office retains some residual powers to protect the constitution and to act in a situation of constitutional crisis; for example, the governor-general can dissolve Parliament under certain circumstances.

The structure of the New Zealand government is relatively simple, but the country's constitutional provisions are more complex. Like that of Great Britain, New Zealand's constitution is a mixture of statute and convention. Where the two clash, convention has tended to prevail. The Constitution Act of 1986 simplified this by consolidating and augmenting constitutional legislation dating from 1852.

The business of government is carried out by some three dozen departments of varying size and importance. Most departments correspond to a ministerial portfolio, department heads being responsible to their respective ministers for administration of their departments. Recruiting and promoting of civil servants is under the control of the State Services Commission, which is independent of partisan politics. Heads of departments and their officials do not change with a change of government, thus ensuring a continuity of administration.

As a check on possible administrative injustices, an office of parliamentary commissioner for investigations (ombudsman) was established in 1962; the scope of the office's jurisdiction was enlarged in 1968 and again in 1975. In addition the Official Information Act of 1982 permits public access, with specific exceptions, to government documents.

There are also a certain number of non-civil service appointees within the government. These fill positions in government corporations—commercial ventures, such as the Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand and the Bank of New Zealand, in which the government is the sole or major stockholder—and in a host of bodies with administrative or advisory functions. Political affiliations, as well as expertise and experience, often figure in appointment decisions for these institutions.

Local government

Local government, which has only limited power in all but peculiarly local matters, is directly empowered by parliamentary statute. Local authorities are thus relatively autonomous, although they do depend upon the central government for financial assistance. The definition of their function and powers is under constant revision as adjustments are made to changing conditions.

Local bodies perform general-purpose duties such as those of counties, boroughs, cities, and town districts, or they consist of ad hoc authorities with specialized functions such as harbour and electric-power boards. Every local authority activity is controlled by an elected council or board of local members, whose work is largely honorary. The platform for election is sometimes based on party affiliation, although this does not noticeably affect the working of the councils or boards.

Justice

New Zealand derives from the common law of Britain certain statutes passed before 1947 by the British Parliament. New Zealand law usually follows the precedents of English law. Nevertheless, the New Zealand courts have taken a more independent stance and have begun to play a more significant constitutional and political role with respect to public and administrative law. In addition some members of the legal community have challenged the traditional doctrine that future Parliaments are not bound by laws passed by the current Parliament, contending that certain common-law rights might override the will of Parliament.

The law is administered by the Ministry of Justice through its courts. A Supreme Court was established by legislation in 2003 (hearings began in 2004), replacing the British Privy Council. Below the Supreme Court, there is a hierarchy of courts dealing with civil and criminal cases, including District Courts, the High Court, and the Court of Appeal. There are also family, youth, and employment courts, as well as the Maori Land Court and the Waitangi Tribunal, which addresses Maori claims of breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi by the government.

Political process

There is universal suffrage for those 18 years of age and older. In 1993 the electorate voted to replace the country's long-standing simple plurality (“first past the post”) system with the mixed member proportional (MMP) method, in which a party's representation in the legislature is proportional to the number of votes its candidates receive. The new system also called for Parliament to be enlarged to 120 seats—69 elected (including 7 reserved for Maoris) and 51 appointed from party lists. The changes went into effect during the 1996 election.

While the MMP system has given a boost to smaller parties, National (New Zealand National Party) and Labour (New Zealand Labour Party) remain New Zealand's two major parties. They each have distinct foundations. National's base of support is in rural and affluent urban districts and among those involved in business and management. Labour draws support from trade unions and urban blue-collar workers. Over time, however, both parties have broadened their electoral bases. Labour has gained the support of some areas of the business sector and has succeeded in attracting more professionals, while the National Party has had some success among higher paid workers in key small-town and provincial districts. Increasingly, ideological differentiation between the two parties has become complex, and intraparty differences in such areas as economic policy have often been greater than they have been between parties.

Security

Participation in the military is voluntary, and individuals must be at least 17 years old to join. The country maintains a relatively small military force, and its defense expenditure as a percentage of the GDP is well below the world average; in 2001 the government eliminated the country's combat air force. Law enforcement is the responsibility of the New Zealand Police, a cabinet-level department largely independent (with respect to law enforcement) of executive authority.

Health and welfare

New Zealand has one of the oldest social security systems in the world. Noncontributory old-age pensions paid for from government revenues were introduced in 1898. Pensions for widows and miners followed soon after, and child allowances were introduced in the 1920s. In 1938 the New Zealand government introduced the most extensive system of pensions and welfare in the world, which included free hospital treatment, free pharmaceutical service, and heavily subsidized treatment by medical practitioners.

Since then the system has been eroded in some respects but greatly extended in others. Doctors' fees, though still subsidized by the state, have become relatively high. Many people invest in private medical insurance and seek treatment in private hospitals instead of in public hospitals. There is still a universal system called New Zealand Superannuation (NZS), in which all citizens over age 65 are granted an income of 65 percent of the average after-tax wage. In 2003, however, this system began to be phased out, replaced by the retirement savings scheme (RSS); the transition is expected to take more than 40 years.

There are numerous other pensions and welfare payments. These include an allowance for each child up to age 16 and additional “family care” payments for low-income families, as well as benefits for single parents, invalids, and the sick. Under the Accident Compensation Act of 1972, all persons suffering personal injury from any sort of accident, whether at work or not, can receive compensation for disability and loss of earnings, and they are covered by insurance for any medical or other treatment; in addition they waive the right to sue for damages. The act led to the establishment of the government-run Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), to which all New Zealanders must pay premiums and which handles claims. The government introduced competition in 1998, allowing businesses to contract private insurers to cover work-related injuries. Two years later, however, this change was reversed, and the ACC again became the sole provider of accident insurance.

Housing

State agencies provide limited financial assistance toward home purchases and renovation work, as well as subsidized rental accommodations for those on low incomes. The state also subsidizes pensioner accommodations through local authorities.

Education

Education in New Zealand is free and secular between the ages of 5 and 19; it is compulsory between the ages of 6 and 16. In practice almost all children enter primary school at age five, while many of them have already begun their education in preschools, all of which are subsidized by the state. Education is administered by the Ministry of Education. Elected education boards control all of the primary and secondary state schools. There are also more than 100 private primary and secondary schools, most of them Roman Catholic or run by other religious groups. They receive state subsidies and must meet certain standards of teaching and accommodation. State primary schools are coeducational, but there are still many single-sex secondary schools.

Technical institutes, community colleges, and teachers' colleges form the basis of higher education. There are several universities and an agricultural college. Entry to the universities requires a modest educational achievement, which is often waived for people 21 years of age or older.

Technical institutes, community colleges, and teachers' colleges form the basis of higher education. There are several universities and an agricultural college. Entry to the universities requires a modest educational achievement, which is often waived for people 21 years of age or older.Education has been strongly emphasized since the early years of the colony, and virtually the entire population is literate. There is a correspondence school that caters to children living in remote places, and various continuing education and adult education centres provide opportunities for lifelong education.

Cultural life

Cultural milieu

New Zealand's cultural influences are predominantly European, but also important are elements from many other peoples, particularly the Maori. Immigrant groups have generally tended to assimilate into the European lifestyle, although traditional customs are still followed by many Tongans, Samoans, and other Pacific Islanders. The Maori, however, have found themselves torn between the pressure to assimilate and the desire to preserve their own culture. The loss of much of their land in the 19th century undermined their political structures, and after most converted to Christianity they abandoned traditional religious observances; but there has been a determined effort since 1950 to preserve and revive artistic and social traditions.

The state has moved progressively since the 1940s to assist and encourage the arts. The Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council gives annual grants in support of theatre, music, modern dance and ballet, and opera, and the New Zealand Literary Fund subsidizes publishers and writers. In addition, New Zealand was one of the first countries to establish a fund to compensate writers for the loss of royalties on books borrowed from libraries rather than purchased. The national orchestra and a weekly cultural publication, the New Zealand Listener, are supported by the government through the Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand. The government also subsidizes a motion-picture industry that has received growing international recognition.

Daily life and social customs

Although European culture predominates in New Zealand, there are attempts to preserve traditional cultures, especially that of the Maori. A renaissance has occurred in Maori wood carving and weaving and in the construction of carved and decorated meeting houses (whare whakairo). Maori songs and dances have become increasingly popular, especially among the young. Maori meetings—whether hui (assemblies) or tangi (funeral gatherings)—are conducted in traditional fashion, with ancient greeting ceremonies strictly observed. The growing Maori movement has generated protests over the country's celebration of Waitangi Day, which commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Although European culture predominates in New Zealand, there are attempts to preserve traditional cultures, especially that of the Maori. A renaissance has occurred in Maori wood carving and weaving and in the construction of carved and decorated meeting houses (whare whakairo). Maori songs and dances have become increasingly popular, especially among the young. Maori meetings—whether hui (assemblies) or tangi (funeral gatherings)—are conducted in traditional fashion, with ancient greeting ceremonies strictly observed. The growing Maori movement has generated protests over the country's celebration of Waitangi Day, which commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.New Zealand cuisine combines traditional British dishes with local delicacies. Fresh seafood is popular along the coasts; mutton, venison, and meat pies are common; and pavlova, a sweet meringue dish, is a popular dessert. As a result of increased tourism and immigration, New Zealand cuisine has begun to move away from simple and conservative British dishes toward more imaginative and cosmopolitan fare, and the number of restaurants, bistros, and cafés in the major cities has skyrocketed in recent years. A traditional Maori meal is hangi, a feast of meat, seafood, and vegetables steamed for hours in an earthen oven (umu).

The arts

European cultural life has progressed rapidly since the early 20th century. Numerous writers (New Zealand literature) were active in the late 19th century, the most successful of whom were historians, such as William Pember Reeves, and ethnologists, including S. Percy Smith and Elsdon Best. The work of the first genuinely original writers of fiction by New Zealanders, the short-story writer Katherine Mansfield (Mansfield, Katherine) and the poet R.A.K. Mason, did not appear until the 1920s. In the 1930s, during the harsh years of the Great Depression, a group of poets appeared and established a national tradition of writing. Although influenced by contemporary English literature—T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden were greatly respected—they wrote about their New Zealand experience. The most notable member of this group was Allen Curnow (Curnow, Allen). A.R.D. Fairburn, Denis Glover, and Charles Brasch were other major poets. At the same time Frank Sargeson (Sargeson, Frank) began writing the superb stories in New Zealand vernacular for which he became well known.

Since World War II the work of these pioneering writers has been followed by that of such widely published and acclaimed poets as James K. Baxter and Kendrick Smithyman. Other notable poets include Ian Wedde and Elizabeth Smither. A number of novelists have also earned international reputations, notably Janet Frame (Frame, Janet), Keri Hulme (Hulme, Keri), Sylvia Ashton-Warner (Ashton-Warner, Sylvia), and mystery writer Ngaio Marsh (Marsh, Ngaio). These and other New Zealand writers have been greatly aided by the growth of the publishing industry in New Zealand during this time.

Painters have also begun to rival writers in artistic accomplishment. The first to achieve international recognition, Frances Hodgkins, spent most of her life abroad. Starting in the 1960s, however, an unprecedented “art scene” emerged, created initially by a group of artists, including Colin McCahon and Don Binney, who were helped by the rise of private galleries in most large towns and cities. While often New Zealand in subject, the paintings clearly reflected international influences. This group paved the way for what has become a small legion of artists.

In the 1970s and '80s professional theatre companies rose to prominence in the major cities—including the Downstage in Wellington and the Mercury Theatre in Auckland—in contrast to earlier companies that folded for want of sufficient audiences. Several symphony orchestras have also had growing support. New Zealand singers who have garnered an international following include Dame Kiri Te Kanawa (Te Kanawa, Dame Kiri), Inia Te Wiata, and Donald McIntyre. The films of New Zealand directors Jane Campion and Peter Jackson have garnered particular notice, as has the work of actor Russell Crowe, who was born in New Zealand.

Beginning in the late 20th century, Maori art has experienced growing popularity and is prominently displayed in numerous galleries and museums. Author Witi Ihimaera has explored the intersection of Maori and pakeha culture. Poet Hone Tuwhare has achieved an international reputation.

Cultural institutions

New Zealand has numerous museums, including Te Papa Tongarewa, the country's national museum. The institution features a number of diverse exhibits, including a re-created island, complete with wildlife. New Zealand is also home to numerous galleries, especially in Auckland and Wellington, that highlight the work of local artists. Theatre is a vital part of the country's culture, and in 1970 the government founded a national drama school, the New Theatre Arts Council Interim Training School (now the New Zealand Drama School). The New Zealand Opera Company also performs.

Sports and recreation

Sports are the main leisure-time activity of most of the population. There is widespread participation in most major sports, particularly rugby football. The inaugural World Cup of rugby, which New Zealand cohosted in 1987, was won by the country's national team, the All Blacks. The opening of each All Black match is highlighted by the players performing the haka known as Ka Mate, a traditional Maori chant accompanied by rhythmic movements, stamping, and fierce gestures. Notable players include Colin Earl Meads (Meads, Colin Earl), who participated in 55 Test matches for the All Blacks.

Sports are the main leisure-time activity of most of the population. There is widespread participation in most major sports, particularly rugby football. The inaugural World Cup of rugby, which New Zealand cohosted in 1987, was won by the country's national team, the All Blacks. The opening of each All Black match is highlighted by the players performing the haka known as Ka Mate, a traditional Maori chant accompanied by rhythmic movements, stamping, and fierce gestures. Notable players include Colin Earl Meads (Meads, Colin Earl), who participated in 55 Test matches for the All Blacks. The climate and the variety of terrain allow for year-round activity in many sports. Mountaineering and hiking are popular outdoor activities, and New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary (Hillary, Sir Edmund) is a national figure. The country has extensive skiing facilities, especially on South Island. Sailing is also much enjoyed, particularly around Auckland Harbour; New Zealand won its first America's Cup yachting race in 1996. Adventure sports have long been common on the islands, and in the late 20th century New Zealand helped popularize bungee jumping.

The climate and the variety of terrain allow for year-round activity in many sports. Mountaineering and hiking are popular outdoor activities, and New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary (Hillary, Sir Edmund) is a national figure. The country has extensive skiing facilities, especially on South Island. Sailing is also much enjoyed, particularly around Auckland Harbour; New Zealand won its first America's Cup yachting race in 1996. Adventure sports have long been common on the islands, and in the late 20th century New Zealand helped popularize bungee jumping.Media and publishing

Newspapers in New Zealand provide a high standard of reporting, with substantial coverage of world news provided largely by foreign agencies. No daily paper has a national circulation, but some from the large cities are distributed widely over their respective islands. Numerous local and regional dailies are also published. The government-run Broadcast Corporation of New Zealand controls Radio New Zealand and both channels of Television New Zealand.

History

Discovery

No precise archaeological records exist of when and from where the first human inhabitants of New Zealand came, but it is generally agreed that Polynesians from eastern Polynesia in the central Pacific reached New Zealand more than 1,000 years ago, possibly by AD 800 or even earlier. There has been much speculation on how these people made the long ocean voyage. Polynesians are known to have sometimes set sail in search of new lands, their canoes well-provisioned with food and plants for cultivation, and it is likely that the discoverers of New Zealand were on such a voyage. It is probable that few canoes made the dangerous journey, but the people from even one of these large, double-hulled craft could have produced the Maori population that the Europeans encountered in New Zealand in the 17th and 18th centuries. With them they brought the dog and the rat and several plants, including the kumara (a variety of sweet potato), taro, and yam.

The Polynesian period has been divided roughly into an early “Archaic” and a later “Classic Maori” phase. The transition between these two phases is uncertain, but it is thought to be linked to improvements in the raising and storage in a cooler climate of what had been tropical vegetables. In the South Island, if not elsewhere, the first Polynesians found moas (flightless birds) in immense numbers on tussock grasslands, and these became their major food supply. The agriculturalist Classic Maori encountered later by Europeans had only faint memories of the moa. The 18th-century Maori population was densest in the warmer northern parts of the country, where the Maori variant of Polynesian culture had reached its high point, particularly in the arts of war, canoe construction, building, weaving, and agriculture.

The first European to arrive in New Zealand was a Dutch sailor, Abel Janszoon Tasman (Tasman, Abel Janszoon), who sighted the coast of Westland in December 1642. His sole attempt to land brought only a clash with a South Island tribe in which several of his men were killed. After his voyage the western coast of New Zealand became a line upon European charts and was thought of as the possible western edge of a great southern continent.

In 1769–70 the British naval officer and explorer James Cook (Cook, James) completed Tasman's work by circumnavigating the two major islands and charting them with a remarkable degree of accuracy. His initial contact with the Maori was violent, but harmonious relations were established later. On this and on subsequent voyages, Cook, with the explorer and naturalist Joseph Banks, made the first systematic observations of Maori life and culture. Cook's journal, published as A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World (1777), brought the knowledge of a new land to Europeans. He stressed the intelligence of the natives and the suitability of the country for colonization, and soon colonists as well as other discoverers followed Cook to the islands he had made known.

In 1769–70 the British naval officer and explorer James Cook (Cook, James) completed Tasman's work by circumnavigating the two major islands and charting them with a remarkable degree of accuracy. His initial contact with the Maori was violent, but harmonious relations were established later. On this and on subsequent voyages, Cook, with the explorer and naturalist Joseph Banks, made the first systematic observations of Maori life and culture. Cook's journal, published as A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World (1777), brought the knowledge of a new land to Europeans. He stressed the intelligence of the natives and the suitability of the country for colonization, and soon colonists as well as other discoverers followed Cook to the islands he had made known.Early European settlement

Apart from convicts escaping from Australia and shipwrecked or deserting sailors seeking asylum with Maori tribes, the first European New Zealanders sought profits—from sealskins, timber, New Zealand flax (genus Phormium), and whaling. Australian firms set up tiny settlements of land-based bay whalers, and Kororareka (now called Russell), in the far north of New Zealand, became a stopping place for American, British, and French deep-sea whalers. Traders supplying whalers drew Maori into their economic activity, buying provisions and supplying trade goods, implements, muskets, and rum. Initially the Maori welcomed the newcomers; while the tribes were secure, the European was a useful dependent.

Maori went overseas, some as far as England. A northern chief, Hongi Hika, amassed presents in England, which he exchanged in Australia for muskets; back in New Zealand he waged devastating war on hereditary enemies. The use of firearms spread southward; a series of tribal wars, spreading from north to south, displaced populations and disturbed landholdings, especially in the Waikato, Taranaki, and Cook Strait areas. Europeans soon founded colonies in these unsettled regions. Missionaries (mission) quickly followed the traders. Between 1814 and 1838 Anglicans, Wesleyan Methodists, and Roman Catholics set up stations. Conversion was initially slow, but by the mid 19th century most Maori adhered, for varying reasons, to some form of Christianity.

All of these newcomers had a profound effect upon Maori life. Warfare and disease reduced numbers, while new values, pursuits, and beliefs modified tribal structure. Christianity cut across the sanctions and prohibitions that had supplied Maori social cohesion. A capitalist economy, to which Maori were introduced both by traders offering new inducements (for instance, the brief demand for New Zealand flax) and by missionaries bringing new agricultural techniques, affected the whole material basis of life. At first in the north and later over the whole country a process of adjustment began, which has continued to the present day. By the late 1830s, chiefly through the Australian link, New Zealand had been joined to Europe. Settlers numbered at least some hundreds, and there were certain to be more. Colonization schemes were afoot in Great Britain, and Australian graziers were buying land from the Maori. These circumstances determined British (British Empire) policy.

Annexation and further settlement

In 1838 the British government decided upon at least partial annexation. In 1839 it commissioned William Hobson, a naval officer, as lieutenant governor and consul to the Maori chiefs, and he annexed the whole country, the North Island by the right of cession from the Maori chiefs and the South Island by the right of discovery. At first New Zealand was legally part of New South Wales; but in 1841 it became a separate crown colony, and Hobson was named governor. Before declaring the annexation of New Zealand, Hobson went through a process of discussion with the northern chiefs from which emerged the Treaty of Waitangi (Waitangi, Treaty of) (February 1840). Under this instrument the Maori ceded sovereignty to the crown in return for protection and guaranteed possession of their lands; they also agreed to sell land only to the crown. Hobson promised an investigation into past “sales” of land to private individuals to ensure fair dealing. This treaty imposed a strong moral obligation upon the British government to act as guardian to the Maori.

Even before annexation had been proclaimed, the first organized planting of an English colony was under way. The New Zealand Association, founded in 1837 to colonize on the principles laid down by Edward Gibbon Wakefield (Wakefield, Edward Gibbon), sent a survey ship, the Tory, in 1839. The agents on board were to buy land in both islands around Cook Strait. The company moved hastily because its founders were aware that British annexation was likely and would entail a crown monopoly of land sales and a consequent increase in price. Purchases were effected in great haste before Hobson could bring to an end such private transactions. Little effort was made to seek out the true Maori owners; this would have been difficult anyway, as Maori ownership was communal and titles had been disturbed by the warfare of the preceding quarter century. The company, combining skillful propaganda with outright trickery and brutality, enforced its claim to the land upon which New Plymouth, Wanganui, and Wellington in the North Island and Nelson in the South Island were founded in the 1840s. Later, through the crown, it secured other areas in the South Island where Otago (1848) and Canterbury (1850) were planted by separate associations. Meanwhile, Hobson moved the seat of government south from the Bay of Islands, bringing Auckland into existence (1840).

In the early 1840s settlement and government began to alarm the Maori. In the Cook Strait area a formidable chief, Te Rauparaha, obstructed settlement. Near the Bay of Islands there was open warfare, and Kororareka was repeatedly raided. Neither Hobson (died 1842) nor his successor, Robert FitzRoy (Fitzroy, Robert), was able to overcome the Maori. George (afterward Sir George) Grey (Grey, Sir George), who became governor in 1845, had money and troops and the will to use them. His victories brought a peace that lasted from 1847 until 1860. Hone Heke, the principal leader in the north, was thoroughly defeated (1846), and in the south a likely uprising was prevented. Racial strife had been accompanied by economic distress. In the mid 1840s the nascent economy was depressed until the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s offered a market for foodstuffs to the New Zealand farmer, settler and Maori alike.

By the end of the 1840s racial and economic trouble gave way to political agitation. The leading settlements, apart from Auckland, began to campaign for representative government in place of Grey's personal rule. He, while refusing to give way, helped to draft the New Zealand Constitution Act of 1852, which was designed to meet all demands of the settlers. Grey sought not to prevent the introduction of self-government but to delay it until he had determined both native and land policy. He wished to begin the rapid assimilation of the Maori (with whom his relations were excellent) to the British pattern. He also wished to bring in a land policy that would safeguard the small farmer against the great owner. He believed he had secured these goals by the time of his departure at the end of 1853.

Responsible government

After the Constitution Act came into operation, New Zealand was divided into six provinces—Auckland, New Plymouth (Taranaki), Wellington, Nelson, Canterbury, and Otago—each with a superintendent and a provincial council. The central government consisted of a governor and a two-chamber legislature (General Assembly): a Legislative Council nominated by the crown, and a House of Representatives elected upon a low property franchise for a five-year term. This General Assembly did not meet until 1854; it then embarked upon a quarrel with the acting governor, Colonel Robert Henry Wynyard, that was not ended until the achievement of full responsible government—i.e., a system under which the governor could act in domestic matters only upon the advice of ministers enjoying the confidence of the elected chamber. Henry Sewell (Sewell, Henry) and James FitzGerald, of Canterbury, led the representatives in this struggle, against the opposition of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who, having first moved the resolution for responsible government, then secretly opposed it while serving as extra-official adviser to the acting governor. The Colonial Office conceded responsible government in 1856. The next governor, Thomas (later Sir Thomas) Gore Browne, reserved Maori affairs to the control of the governor alone.

For most purposes, during the 1850s New Zealand was administered not by central but by provincial institutions. These authorities (10 in number by the time of their abolition in 1876) directly affected the settler through their administration of land and control of immigration and public works. The native department, directly under the governor, bought land from the Maori; the provincial governments settled it, regulated immigration, and built roads and bridges. Until the wars of the 1860s the central legislature was less important, though its ultimate authority remained.