Odonata

insect order

Introduction

insect order comprising the dragonflies (dragonfly) (suborder Anisoptera) and the damselflies (damselfly) (suborder Zygoptera). The adults are easily recognized by their two pairs of narrow, transparent wings, sloping thorax, and long, usually slender body; the abdomen is almost always longer than any of the wings. Large, active by day, and often strikingly coloured, they are usually seen flying near water. Adult odonates are voracious predators, as are the aquatic larvae.

insect order comprising the dragonflies (dragonfly) (suborder Anisoptera) and the damselflies (damselfly) (suborder Zygoptera). The adults are easily recognized by their two pairs of narrow, transparent wings, sloping thorax, and long, usually slender body; the abdomen is almost always longer than any of the wings. Large, active by day, and often strikingly coloured, they are usually seen flying near water. Adult odonates are voracious predators, as are the aquatic larvae. The name dragonfly is commonly applied to all odonates, but it is also used to differentiate the suborder Anisoptera from the suborder Zygoptera. The order Odonata is small and well known; the total number of living species probably does not greatly exceed the 5,000 or so already described. Odonates are globally distributed from the tropics, where they are most numerous and varied, to the boreal forests (boreal forest) of Siberia and North America. They are also found throughout the Southern Hemisphere, with the exception of Antarctica.

The name dragonfly is commonly applied to all odonates, but it is also used to differentiate the suborder Anisoptera from the suborder Zygoptera. The order Odonata is small and well known; the total number of living species probably does not greatly exceed the 5,000 or so already described. Odonates are globally distributed from the tropics, where they are most numerous and varied, to the boreal forests (boreal forest) of Siberia and North America. They are also found throughout the Southern Hemisphere, with the exception of Antarctica. While the basic structure of adults is uniform, coloration is highly variable—hues range from metallic to dull, sometimes in combination. There is also a wide range of sizes; damselfly species have both the shortest and longest wingspans—about 18 mm and 19 cm (0.71 inch and 7.5 inches), respectively. However, some fossil ancestors of today's odonates had wingspans of more than 70 cm (28 inches).

While the basic structure of adults is uniform, coloration is highly variable—hues range from metallic to dull, sometimes in combination. There is also a wide range of sizes; damselfly species have both the shortest and longest wingspans—about 18 mm and 19 cm (0.71 inch and 7.5 inches), respectively. However, some fossil ancestors of today's odonates had wingspans of more than 70 cm (28 inches).Odonates are among the few insects that have secured a major place in folklore and art. In Japan, where a journal (Tombo) has been devoted to reports of their biology since 1958, dragonflies (Odonata) traditionally have been held in high regard. In other Asian cultures they are considered benign and auspicious, but in Europe they have often been perceived as threatening, even though they do not injure humans. Long-standing vernacular names such as horse stinger, snake doctor, and devil's darning needle testify to their formidable appearance.

The young, termed larvae or sometimes nymphs, are functionally wingless and live in a variety of shallow freshwater habitats including tree holes, ponds, marshes, and streams. They are often bottom-dwelling and are well-camouflaged, their mottled or drab colours matching the sediments or water plants around them. Although large numbers of mosquitoes and other insect pests are consumed by larvae and adults, odonates are generally indiscriminate feeders that seldom affect humans economically. Larvae, however, have been used successfully in Myanmar to interrupt transmission of the mosquito-borne disease dengue.

Natural history

The larval stage

Eggs are laid in or very near water (exceptions include the terrestrial larvae of a few Hawaiian damselflies (Megalagrion) and Australian woodland dragonflies of the genus Pseudocordulia). The hatchlings then develop through a series of stages, or instars, molting at the end of each instar into similar, but larger and more developed, versions of themselves. Very soon after leaving the egg, the first instar (prolarva) sheds its cuticular (cuticle) sheath, releasing the tiny, spiderlike larva. Because it is aquatic, the larva differs markedly in structure and behaviour from the flight-oriented adult. Wing sheaths are not even apparent in the early instars; it is not until about halfway through larval development that they appear, becoming rapidly larger during subsequent molts. Larvae molt approximately 8 to 17 times, and some grow to more than 5 cm (2 inches) in length. The number of instars varies both within and between species. Early instars feed actively on various small water animals, including tiny crustaceans and protozoans; during later instars the larva feeds on larger prey such as midge larvae, aquatic beetles, snails, and even small fishes.

Eggs are laid in or very near water (exceptions include the terrestrial larvae of a few Hawaiian damselflies (Megalagrion) and Australian woodland dragonflies of the genus Pseudocordulia). The hatchlings then develop through a series of stages, or instars, molting at the end of each instar into similar, but larger and more developed, versions of themselves. Very soon after leaving the egg, the first instar (prolarva) sheds its cuticular (cuticle) sheath, releasing the tiny, spiderlike larva. Because it is aquatic, the larva differs markedly in structure and behaviour from the flight-oriented adult. Wing sheaths are not even apparent in the early instars; it is not until about halfway through larval development that they appear, becoming rapidly larger during subsequent molts. Larvae molt approximately 8 to 17 times, and some grow to more than 5 cm (2 inches) in length. The number of instars varies both within and between species. Early instars feed actively on various small water animals, including tiny crustaceans and protozoans; during later instars the larva feeds on larger prey such as midge larvae, aquatic beetles, snails, and even small fishes.Larval development can range from three weeks to more than 8 years, depending on the species and habitat. Tropical species generally take less time to develop than those of colder climates. Many temperate species spend their last winter in the final instar and emerge during the spring and early summer. Others spend their last winter as eggs, earlier instars, or immature adults. Odonate larvae are preyed upon mainly by fish but also by frogs, birds, crayfish, and each other. Both larvae and adults are sometimes parasitized by flukes, tapeworms, and mites; minute wasps can parasitize eggs. During emergence odonates are particularly vulnerable to predation by birds, spiders, amphibians, and reptiles.

There is no pupal stage among odonates, but toward the end of the last instar the larva stops feeding, and its organs transform into those of an adult within the larval skin. A few days later it climbs out of the water on a suitably robust support (usually vegetation) and molts to disclose the adult—a process known as emergence. If the air temperature is high enough, the largest dragonflies will leave the water after sunset and take flight just before sunrise; smaller species typically emerge during the day.

There is no pupal stage among odonates, but toward the end of the last instar the larva stops feeding, and its organs transform into those of an adult within the larval skin. A few days later it climbs out of the water on a suitably robust support (usually vegetation) and molts to disclose the adult—a process known as emergence. If the air temperature is high enough, the largest dragonflies will leave the water after sunset and take flight just before sunrise; smaller species typically emerge during the day.The adult stage

The newly emerged adult dragonfly is soft, pale, and reproductively immature. After the wings straighten and the body hardens, one of its first actions is to fly away from water and begin feeding, although a day or more may separate the first flight from the first meal. Once it has left the emergence site, the adult has few regular enemies. In flight adults are able to evade almost all predators except for extremely agile birds such as bee-eaters (bee-eater) and falcons. Frogs are regular predators at egg-laying sites.

The newly emerged adult dragonfly is soft, pale, and reproductively immature. After the wings straighten and the body hardens, one of its first actions is to fly away from water and begin feeding, although a day or more may separate the first flight from the first meal. Once it has left the emergence site, the adult has few regular enemies. In flight adults are able to evade almost all predators except for extremely agile birds such as bee-eaters (bee-eater) and falcons. Frogs are regular predators at egg-laying sites.Adult life consists of two phases—the prereproductive, or maturation, period and the reproductive period. Maturation generally lasts about 2 weeks but can take anywhere from 1 to 60 days, depending on species, climate, and weather. When the maturation period serves to bridge dry or cold seasons, however, it can last nine months or more.

The reproductive period begins when a sexually mature adult dragonfly flies to the mating rendezvous, usually the margin of a body of water where the eggs will be laid. Males assemble there slightly earlier than females and space themselves along the shore or over the water. At the rendezvous site defense by males ranges from negligible to intense. Actively defending males establish an area of characteristic extent, much as birds defend territories (territorial behaviour). Where sites are intensely defended, an individual may return to the same perch for many successive days and expel intruders. When a male adult approaches or enters a territory occupied by another individual of the same species, the occupant acts aggressively, and an aerial agility contest often ensues; thus, territories are held by the most vigorous males. Violent confrontations between rival males sometimes result in injury or death. If a female adult approaches or enters a territory, the resident male tries to mate with her. In some species mating is preceded by a courtship display during which the female accepts or rejects the male, who tries to guide her to an egg-laying site in his territory. Usually, however, there is no evident prelude and mating occurs immediately.

The mating posture is unique among insects. With the claspers at the end of his abdomen, the male grasps the top of the female's head or prothorax, thus forming the tandem position. The male's movements then induce her to bring the tip of her abdomen forward so that it meets his accessory sex organs at the base of his abdomen, where he has deposited the sperm. This so-called “wheel” position enables the female to receive her partner's sperm. The wheel can be formed in flight, and, although mated adults usually alight promptly, many odonates are able to fly together this way—a remarkable and elegant sight. The couple remains joined in this way for a few seconds to several hours, depending on the species. Little of this time, however, is spent actually transferring sperm. Instead, the male is mainly occupied with using his accessory sex organs to displace sperm that may have been deposited in the female by previous mates.

The mating posture is unique among insects. With the claspers at the end of his abdomen, the male grasps the top of the female's head or prothorax, thus forming the tandem position. The male's movements then induce her to bring the tip of her abdomen forward so that it meets his accessory sex organs at the base of his abdomen, where he has deposited the sperm. This so-called “wheel” position enables the female to receive her partner's sperm. The wheel can be formed in flight, and, although mated adults usually alight promptly, many odonates are able to fly together this way—a remarkable and elegant sight. The couple remains joined in this way for a few seconds to several hours, depending on the species. Little of this time, however, is spent actually transferring sperm. Instead, the male is mainly occupied with using his accessory sex organs to displace sperm that may have been deposited in the female by previous mates. After mating, the female usually lays eggs (egg) immediately. She may do so alone, or her partner may be still attached in tandem or hovering nearby, darting at other males that approach. Such guarding is extremely important to the male, as the one that mates last with the female is the one whose sperm first fertilizes the eggs laid during the next day or so. Eggs are laid in several ways. Species with a well-formed ovipositor place them either within or on plant tissue, above or in the water. Some climb beneath the water's surface to lay and may remain submerged for an hour or more. Species without an ovipositor dip the abdomen in water (sometimes while in flight) and wash the eggs off or stick them onto leaves of plants close to the water's surface. Others drop them through the air onto the water's surface. Eggs that are laid in running water usually possess adhesive or tangling devices that prevent their being swept downstream.

After mating, the female usually lays eggs (egg) immediately. She may do so alone, or her partner may be still attached in tandem or hovering nearby, darting at other males that approach. Such guarding is extremely important to the male, as the one that mates last with the female is the one whose sperm first fertilizes the eggs laid during the next day or so. Eggs are laid in several ways. Species with a well-formed ovipositor place them either within or on plant tissue, above or in the water. Some climb beneath the water's surface to lay and may remain submerged for an hour or more. Species without an ovipositor dip the abdomen in water (sometimes while in flight) and wash the eggs off or stick them onto leaves of plants close to the water's surface. Others drop them through the air onto the water's surface. Eggs that are laid in running water usually possess adhesive or tangling devices that prevent their being swept downstream.Form and function

Adults

Basic structure

The principal structural features of adult odonates reflect adaptations to flight. Adults have two pairs of narrow, typically transparent wings and a long, slender abdomen consisting of 10 segments. The head has prominent eyes and inconspicuous antennae, and the thorax is tilted along the body's axis. The sloping thorax accommodates very large wing muscles and sets the legs forward, where they can best grasp prey. Consequently, odonates are well adapted to perching but are largely unable to walk on flat surfaces. Where the head joins the thorax, a delicate orientation organ maintains equilibrium during flight.

The principal structural features of adult odonates reflect adaptations to flight. Adults have two pairs of narrow, typically transparent wings and a long, slender abdomen consisting of 10 segments. The head has prominent eyes and inconspicuous antennae, and the thorax is tilted along the body's axis. The sloping thorax accommodates very large wing muscles and sets the legs forward, where they can best grasp prey. Consequently, odonates are well adapted to perching but are largely unable to walk on flat surfaces. Where the head joins the thorax, a delicate orientation organ maintains equilibrium during flight.Odonates are considered to have excellent vision, and the large compound eyes (eye, human), acutely responsive to movement and form, play an important role in capturing food and interacting with other individuals. In most dragonflies (suborder Anisoptera) the compound eyes meet at the top of the head and can consist of 30,000 individual optical units, or ommatidia. Their large eyes give some anisopterans a nearly 360-degree view of their environment. Among certain dragonflies of the family Aeshnidae that fly only in subdued light (e.g., Gynacantha), the eyes occupy almost the entire surface of the head. Damselflies (suborder Zygoptera), on the other hand, have eyes that are well separated. Odonates also possess three tiny simple eyes called ocelli.

At the opposite end of the body, another structural difference between the two suborders can be seen: male damselflies have four tail appendages, whereas dragonflies have only three.

Wings and flight

The large wings (wing) are strengthened by a complex network of veins. Each wing also has a thickened patch (the pterostigma) on the leading edge of the wing tip. The forewings of dragonflies are narrower than the hind wings, which in certain migratory species (genera Libellula, Pantala, and Tramea) are expanded, permitting gliding flight.

Odonates use their wings in a unique manner. Whereas other insects with four wings beat them synchronously, odonates can beat the fore and hind pairs independently. This allows three different modes of flight in which the pairs beat (1) synchronously, as those of other insects, (2) alternately between the two sets, or (3) synchronously but out of phase with each other. Such variations allow odonates a repertoire of aerobatic abilities that include hovering, backward flight, and turns of such tight radius that they are virtually midair pivots. Odonate aerodynamics have even been studied in the hope of applying the flight principles involved to aircraft.

Reproduction

The unique wheel position exhibited by Odonata can be regarded as a special way of transferring sperm. Instead of placing sperm on the ground or a leaf for the female to pick up (as certain primitive insects do), the male transfers it from genitalia near the tip of his abdomen to accessory sex organs at the base of his abdomen that are specially constructed to receive and transmit sperm to the female. Odonates that appear very similar may actually be different species; the sex organs are highly intricate and species-specific. Males have evolved various means of displacing the sperm of previous mates. Mating between species is hampered by the fact that odonates of the same species have interlocking structures on the male claspers and female head or prothorax that enable the wheel to be formed and made secure.

Larvae

Basic structure

Like the adults, odonate larvae have large eyes, and anisopterans are generally stockier than zygopterans. The most immediate method of distinguishing between larvae of the two suborders is by inspecting the abdomen. In most Zygoptera there are three external leaflike plates at the tip of the abdomen that function as gills. Among anisopterans the gills are internal growths of the hindgut wall that are ventilated as water is pumped in and out of the anus. Both respiratory systems are used in emergencies as methods for locomotion; jet propulsion via the anus is a particularly effective escape tactic employed by Anisoptera. Many zygopterans, on the other hand, use their leaflike plates to swim much as a fish uses its tail.

Unlike the adults, the larvae show many structural variations that reflect the demands of different aquatic microhabitats with respect to respiration, locomotion, feeding, and concealment. Species living within fine sediment (Aphylla), for example, are more or less cylindrical in cross-section, with a terminal siphon that maintains respiratory contact with the water above; those residing on the surface of mud or sand (Ictinogomphus) often are flattened, with prominent lateral spines on the abdomen; those living among plants near the surface (Anax, Lestes) are streamlined and very active.

Feeding

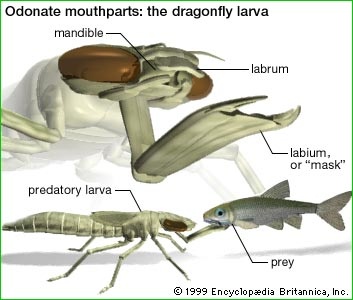

A larva captures prey in a very unusual way. Typically, it remains motionless until a victim is detected by sight or touch. When prey comes within range, the larva shoots out its highly developed, prehensile lower mouthpart (the labium), seizing the victim with the pincers at the end of it. The prey is then drawn back to the mandibles, where it is chewed and consumed. In the resting position the labium lies beneath the head and thorax, sometimes obscuring the front of the head; hence, it is commonly called the “mask.” It can be extended almost instantaneously (under 3/100 second) by a localized increase in blood pressure that is controlled by abdominal muscles.

A larva captures prey in a very unusual way. Typically, it remains motionless until a victim is detected by sight or touch. When prey comes within range, the larva shoots out its highly developed, prehensile lower mouthpart (the labium), seizing the victim with the pincers at the end of it. The prey is then drawn back to the mandibles, where it is chewed and consumed. In the resting position the labium lies beneath the head and thorax, sometimes obscuring the front of the head; hence, it is commonly called the “mask.” It can be extended almost instantaneously (under 3/100 second) by a localized increase in blood pressure that is controlled by abdominal muscles.Evolution, paleontology, and classification

The odonates have an unusually long and rich fossil record. Ancestors date from more than 300 million years ago (the Late Carboniferous Epoch) and predate the dinosaurs by nearly 100 million years. Closely resembling present dragonflies, they had already diverged from other orders of winged insects, including their closest living relatives, the mayflies (order Ephemeroptera). The oldest odonate ancestors are of the extinct order Protodonata, and even they possessed a complete series of alternating upwardly and downwardly curving wing veins, as do today's odonates. Protodonate wings, however, lacked the pterostigma. Also extinct is the suborder Meganisoptera of the Carboniferous and Permian periods. This suborder includes well-preserved fossils of gigantic dragonflies such as Meganeura monyi, which had a wingspan of more than 70 cm (28 inches).

The order Odonata contains four extinct and two living suborders. Extinct suborders are Protanisoptera and Archizygoptera of the Permian Period, Triadophlebiomorpha of the Triassic Period, and Anisozygoptera of the Triassic to Cretaceous periods. The only living suborders are Anisoptera and Zygoptera. Two odd and primitive species, both of the genus Epiophlebia (family Epiophlebiidae), live in the mountains of Nepal and Japan; until recently, they were classified as Anisozygoptera, a suborder intermediate in form between current dragonflies and damselflies. Another relict, or “living fossil,” group is the family Hemiphlebiidae. Like the epiophlebiids, members of this family (found only in a small Australian locale) are primitive and sufficiently different from all other odonates to warrant their own superfamily.

Taxonomy and classification

Features used by taxonomists when classifying adult members of the order Odonata are the structure of the male sex organs, shape and vein patterns of the wings, distance between the compound eyes, form and development of rear appendages, and presence of an ovipositor. Larvae are classified according to the type and form of respiratory organ, labial structure, number and arrangement of body spines, and shape of the abdomen.

The members of the order Odonata occupy a uniquely isolated position in the phylogeny of insects, representing a remarkable mixture of primitive and specialized characteristics. The classification given here is essentially that of F.M. Carpenter (1992) and C.A. Bridges (1993); it takes into account the fossil record of ancestral odonates. Other recently proposed classifications exist.

Order Odonata

Odonata, meaning “toothed-ones,” comprises over 5,000 living species, all of which are assigned to suborders Zygoptera (damselflies (damselfly)) and Anisoptera (dragonflies (dragonfly)). The number of species in each suborder is roughly the same. The 8 living superfamilies are divided into 27 families and slightly over 600 genera.

Suborder Zygoptera (damselflies)

Nineteen living families among four superfamilies. Two extinct families are not listed. Almost half of all zygopteran species are of the family Coenagrionidae.

Superfamily Hemiphlebioidea

Family Hemiphlebiidae

Superfamily Coenagrionoidea

Family Coenagrionidae

Family Isostictidae

Family Platycnemididae

Family Platystictidae

Family Protoneuridae

Family Pseudostigmatidae

Superfamily Lestoidea

Family Lestidae

Family Lestoideidae

Family Megapodagrionidae

Family Perilestidae

Family Pseudolestidae

Family Synlestidae

Superfamily Calopterygoidea

Family Amphipterygidae

Family Calopterygidae

Family Chlorocyphidae

Family Dicteriadidae

Family Euphaeidae

Family Polythoridae

Suborder Anisoptera (dragonflies)

Eight living families (including Epiophlebiidae, formerly classified in Anisozygoptera) among four superfamilies. Five extinct families are not listed.

Superfamily Aeshnoidea

Family Aeshnidae

Family Gomphidae

Family Neopetaliidae

Family Petaluridae

Superfamily Cordulegastroidea

Family Cordulegastridae

Superfamily Epiophlebioidea

Family Epiophlebiidae

Superfamily Libelluloidea

Family Corduliidae

Family Libellulidae

Critical appraisal

There is general agreement among specialists regarding the status and affinities of living families and genera of the Odonata, and with few exceptions published classifications based on the adult and larva correspond with one another. The phylogeny of the two living suborders, however, remains debatable. The primary issue is whether Anisoptera arose independently from the Protodonata or descended from zygopteroid stock—perhaps the extinct Archizygoptera. The former hypothesis receives wider support.

Additional Reading

Recommended resources fall into three categories: General sources that are commonly available to the public; Guides, which function as identification or classification aids but may not be commonly available outside of university and research libraries; and Technical, which address advanced topics in detail.

General

Books

Philip S. Corbet, Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata (1999), a definitive and heavily illustrated source of information covering both dragonflies and damselflies.Ross E. Hutchins, The World of Dragonflies and Damselflies (1969), in addition to basic biological information, includes discussion of fossil ancestors and suggestions for collecting, identifying, and studying odonates.Rod Preston-Mafham and Ken Preston-Mafham, The Encyclopedia of Land Invertebrate Behaviour (1993), pp. 35–42, includes a detailed discussion of odonate reproductive behaviour, in addition to other topics briefly touched upon.

Video documentaries

The Dragon & the Damsel (1983), written and produced by Pelham Aldrich-Blake. Narrated by Sir David Attenborough as part of the BBC natural history series “Wildlife on One.” Dragonfly (1988), produced by NHK Japan and TVOntario as part of the “Nature Watch” series.

Guides

The titles cited below are Classification guides, which treat taxonomic relationships among groups, and Field and identification guides, which are used to determine the name of a given specimen.

Classification

Frederick C. Fraser, A Reclassification of the Order Odonata (1957), the definitive work on classification.Charles A. Bridges, Catalogue of the Family-group, Genus-group, and Species-group Names of the Odonata of the World, 3rd ed. (1994), a definitive and comprehensive listing.Shigeru Tsuda, A Distribution List of World Odonata (1986), a catalog listing the countries in which all described species occur.Henrik Steinmann, World Catalogue of Odonata (1997), parts 110 and 111 of “The Animal Kingdom” series. A 2-volume set in which each volume is devoted to a living suborder, this is a largely historical rather than contemporary taxonomic compilation.

Field and identification

Richard R. Askew, The Dragonflies of Europe (1988). J.A.L. Watson, G. Theischinger, and H.M. Abbey, The Australian Dragonflies (1991).Viacheslav G. Mordkovich (ed.), Fauna i ekologiia strekoz (1989), on odonates of the former Soviet Union.Frederick C. Fraser, Odonata, 3 vol. (1933–36), in “The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma” series.James G. Needham and Minter J. Westfall, Jr., A Manual of the Dragonflies of North America (Anisoptera) (1954, reissued 1975).Minter J. Westfall, Jr., and Michael L. May, Damselflies of North America (1996).Elliot C.G. Pinhey, A Survey of the Dragonflies of Eastern Africa (1961).Elliot C.G. Pinhey, The Dragonflies of Southern Africa (1951, reprinted 1979).

Technical

The sources listed below are intended for odonatologists. Listings include both current and classic texts and articles. Philip S. Corbet, A Biology of Dragonflies (1962, reprinted 1983), a college-level textbook emphasizing ecology and behaviour.Robin J. Tillyard, The Biology of Dragonflies (Odonata or Paraneuroptera) (1917), a classic college-level textbook emphasizing systematics and functional morphology.Jonathan K. Waage, “Sperm Competition and the Evolution of Odonate Mating Systems,” in Robert L. Smith (ed.), Sperm Competition and the Evolution of Animal Mating Systems (1984). Syoziro Asahina, A Morphological Study of a Relic Dragonfly Epiophlebia superstes Selys (Odonata, Anisozygoptera) (1954), a comprehensive study of one of the two “living fossil” species of the family Epiophlebiidae. Norman W. Moore, Dragonflies (1997), status survey and conservation action plan for endangered dragonflies, as proposed by the Odonata Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).Frank M. Carpenter, Superclass Hexapoda, vol. 3–4 (1992), in Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part R, Arthropoda 4, a review of odonate paleontology.Philip S. Corbet, “A Brief History of Odonatology,” Advances in Odonatology, 5:21–44 (1991).

- Crewe and Nantwich

- crewel work

- Crews, Frederick C.

- crib

- cribbage

- Cribb, Tom

- Crichton, James

- Crichton, Michael

- Criciúma

- cricket

- cricket frog

- Cricket World Cup

- Crick, Francis Harry Compton

- Cricklade

- cri-du-chat syndrome

- Crile, George Washington

- crime

- Crimea

- Crimea, khanate of the

- Crimean Astrophysical Observatory

- Crimean Peninsula

- Crimean War

- crime, délit, and contravention

- criminal investigation

- criminal justice