Olympic Games

Introduction

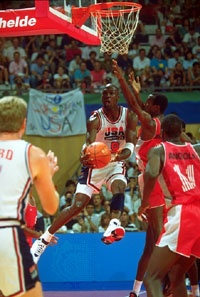

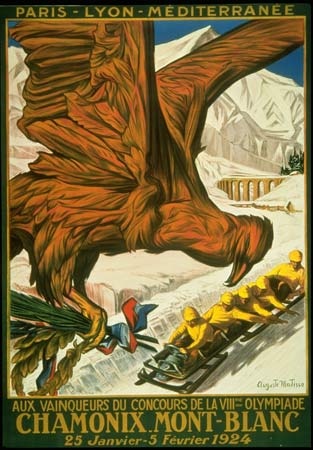

athletic festival that originated in ancient Greece (ancient Greek civilization) and was revived in the late 19th century. Before the 1970s the Games were officially limited to competitors with amateur status, but in the 1980s many events were opened to professional athletes. Currently the Games are open to all, even the top professional athletes in basketball and football (soccer). The ancient Olympic Games included several of the sports that are now part of the Summer Games program, which at times has included events in as many as 32 different sports. In 1924 the Winter Games were sanctioned for winter sports. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world's foremost sports competition. For coverage of the 2008 Olympics, see Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom.

The ancient Olympic Games

Origins

Just how far back in history organized athletic contests were held remains a matter of debate, but it is reasonably certain that they occurred in Greece almost 3,000 years ago. However ancient in origin, by the end of the 6th century BC at least four Greek sporting festivals, sometimes called “classical games,” had achieved major importance: the Olympic Games, held at Olympia; the Pythian Games at Delphi; the Nemean Games at Nemea; and the Isthmian Games, held near Corinth. Later, similar festivals were held in nearly 150 cities as far afield as Rome, Naples, Odessus, Antioch, and Alexandria.

Just how far back in history organized athletic contests were held remains a matter of debate, but it is reasonably certain that they occurred in Greece almost 3,000 years ago. However ancient in origin, by the end of the 6th century BC at least four Greek sporting festivals, sometimes called “classical games,” had achieved major importance: the Olympic Games, held at Olympia; the Pythian Games at Delphi; the Nemean Games at Nemea; and the Isthmian Games, held near Corinth. Later, similar festivals were held in nearly 150 cities as far afield as Rome, Naples, Odessus, Antioch, and Alexandria.Of all the games held throughout Greece, the Olympic Games were the most famous. Held every four years between August 6 and September 19, they occupied such an important place in Greek history that in late antiquity historians measured time by the interval between them—an Olympiad. The Olympic Games, like almost all Greek games, were an intrinsic part of a religious festival. They were held in honour of Zeus at Olympia by the city-state of Elis in the northwestern Peloponnese. The first Olympic champion listed in the records was Coroebus of Elis, a cook, who won the sprint race in 776 BC. Notions that the Olympics began much earlier than 776 BC are founded on myth, not historical evidence. According to one legend, for example, the Games were founded by Heracles, son of Zeus and Alcmene.

Competition and status

At the meeting in 776 BC there was apparently only one event, a footrace that covered one length of the track at Olympia, but other events were added over the ensuing decades. The race, known as the stade, was about 192 metres (210 yards) long. The word stade also came to refer to the track on which the race was held and is the origin of the modern English word stadium. In 724 BC a two-length race, the diaulos, roughly similar to the 400-metre race, was included, and four years later the dolichos, a long-distance race possibly comparable to the modern 1,500- or 5,000-metre events, was added. wrestling and the pentathlon were introduced in 708 BC. The latter was an all-around competition consisting of five events—the long jump, the javelin throw, the discus throw, a footrace, and wrestling.

boxing was introduced in 688 BC and chariot racing eight years later. In 648 BC the pancratium (from Greek pankration), a kind of no-holds-barred combat, was included. This brutal contest combined wrestling, boxing, and street fighting. Kicking and hitting a downed opponent were allowed; only biting and gouging (thrusting a finger or thumb into an opponent's eye) were forbidden. Between 632 and 616 BC events for boys were introduced. And from time to time further events were added, including a footrace in which athletes ran in partial armour and contests for heralds and for trumpeters. The program, however, was not nearly so varied as that of the modern Olympics. There were neither team games nor ball games, and the athletics (track and field) events were limited to the four running events and the pentathlon mentioned above. Chariot races and horse racing, which became part of the ancient Games, were held in the hippodrome south of the stadium.

In the early centuries of Olympic competition, all the contests took place on one day; later the Games were spread over four days, with a fifth devoted to the closing-ceremony presentation of prizes and a banquet for the champions. In most events the athletes participated in the nude. Through the centuries scholars have sought to explain this practice. Theories have ranged from the eccentric (to be nude in public without an erection demonstrated self-control) to the usual anthropological, religious, and social explanations, including the following: (1) nudity bespeaks a rite of passage, (2) nudity was a holdover from the days of hunting and gathering, (3) nudity had, for the Greeks, a magical power to ward off harm, and (4) public nudity was a kind of costume of the upper class. Historians grasp at dubious theories because, in Judeo-Christian society, to compete nude in public seems odd, if not scandalous. Yet ancient Greeks found nothing shameful about nudity, especially male nudity. Therefore, the many modern explanations of Greek athletic nudity are in the main unnecessary.

The Olympic Games were technically restricted to freeborn Greeks. Many Greek competitors came from the Greek colonies on the Italian peninsula and in Asia Minor and Africa. Most of the participants were professionals who trained full-time for the events. These athletes earned substantial prizes for winning at many other preliminary festivals, and, although the only prize at Olympia was a wreath or garland, an Olympic champion also received widespread adulation and often lavish benefits from his home city.

Women and the Olympic Games

Although there were no women's events in the ancient Olympics, several women appear in the official lists of Olympic victors as the owners of the stables of some victorious chariot entries. In Sparta, girls and young women did practice and compete locally. But, apart from Sparta, contests for young Greek women were very rare and probably limited to an annual local footrace. At Olympia, however, the Herean festival, held every four years in honour of the goddess Hera, included a race for young women, who were divided into three age groups. Yet the Herean race was not part of the Olympics (they took place at another time of the year) and probably was not instituted before the advent of the Roman Empire. Then for a brief period girls competed at a few other important athletic venues.

The 2nd-century-AD traveler Pausanias wrote that women were banned from Olympia during the actual Games under penalty of death. Yet he also remarked that the law and penalty had never been invoked. His account later incongruously stated that unmarried women were allowed as Olympic spectators. Many historians believe that a later scribe simply made an error copying this passage of Pausanias's text here. Nonetheless, the notion that all or only married women were banned from the Games endured in popular writing on the topic, though the evidence regarding women as spectators remains unclear.

Demise of the Olympics

Greece lost its independence to Rome (ancient Rome) in the middle of the 2nd century BC, and support for the competitions at Olympia and elsewhere fell off considerably during the next century. The Romans looked on athletics with contempt—to strip naked and compete in public was degrading in their eyes. The Romans realized the political value of the Greek festivals, however, and Emperor Augustus staged games for Greek athletes in a temporary wooden stadium erected near the Circus Maximus in Rome and instituted major new athletic festivals in Italy and in Greece. Emperor Nero was also a keen patron of the festivals in Greece, but he disgraced himself and the Olympic Games when he entered a chariot race (chariot racing), fell off his vehicle, and then declared himself the winner anyway.

Romans neither trained for nor participated in Greek athletics. Roman gladiator shows and team chariot racing were not related to the Olympic Games or to Greek athletics. The main difference between the Greek and Roman attitudes is reflected in the words each culture used to describe its festivals: for the Greeks they were contests (agōnes), while for the Romans they were games (ludi). The Greeks originally organized their festivals for the competitors, the Romans for the public. One was primarily competition, the other entertainment. The Olympic Games were finally abolished about AD 400 by the Roman emperor Theodosius I or his son because of the festival's pagan associations.

The modern Olympic movement

Revival of the Olympics

The ideas and work of several people led to the creation of the modern Olympics. The best-known architect of the modern Games was Pierre, baron de Coubertin (Coubertin, Pierre, baron de), born in Paris on New Year's Day, 1863. Family tradition pointed to an army career or possibly politics, but at age 24 Coubertin decided that his future lay in education, especially physical education. In 1890 he traveled to England to meet Dr. William Penny Brookes, who had written some articles on education that attracted the Frenchman's attention. Brookes also had tried for decades to revive the ancient Olympic Games, getting the idea from a series of modern Greek Olympiads held in Athens starting in 1859. The Greek Olympics were founded by Evangelis Zappas, who, in turn, got the idea from Panagiotis Soutsos, a Greek poet who was the first to call for a modern revival and began to promote the idea in 1833. Brookes's first British Olympiad, held in London in 1866, was successful, with many spectators and good athletes in attendance. But his subsequent attempts met with less success and were beset by public apathy and opposition from rival sporting groups. Rather than give up, in the 1880s Brookes began to argue for the founding of international Olympics in Athens.

When Coubertin sought to confer with Brookes about physical education, Brookes talked more about Olympic revivals and showed him documents relating to both the Greek and the British Olympiads. He also showed Coubertin newspaper articles reporting his own proposal for international Olympic Games. On November 25, 1892, at a meeting of the Union des Sports Athlétiques in Paris, with no mention of Brookes or these previous modern Olympiads, Coubertin himself advocated the idea of reviving the Olympic Games, and he propounded his desire for a new era in international sport when he said:

Let us export our oarsmen, our runners, our fencers into other lands. That is the true Free Trade of the future; and the day it is introduced into Europe the cause of Peace will have received a new and strong ally.

He then asked his audience to help him in “the splendid and beneficent task of reviving the Olympic Games.” The speech did not produce any appreciable activity, but Coubertin reiterated his proposal for an Olympic revival in Paris in June 1894 at a conference on international sport attended by 79 delegates representing 49 organizations from 9 countries. Coubertin himself wrote that, except for his coworkers Dimítrios Vikélas of Greece, who was to be the first president of the International Olympic Committee, and Professor William M. Sloane of the United States, from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), no one had any real interest in the revival of the Games. Nevertheless, and to quote Coubertin again, “a unanimous vote in favour of revival was rendered at the end of the Congress chiefly to please me.”

It was at first agreed that the Games should be held in Paris in 1900. Six years seemed a long time to wait, however, and it was decided (how and by whom remains obscure) to change the venue to Athens and the date to April 1896. A great deal of indifference, if not opposition, had to be overcome, including a refusal by the Greek prime minister to stage the Games at all. But when a new prime minister took office, Coubertin and Vikélas were able to carry their point, and the Games were opened by the king of Greece in the first week of April 1896, on Greek Independence Day.

Organization

The International Olympic Committee

At the Congress of Paris in 1894, the control and development of the modern Olympic Games were entrusted to the International Olympic Committee (IOC; Comité International Olympique). During World War I Coubertin moved its headquarters to Lausanne, Switzerland, where they have remained. The IOC is responsible for maintaining the regular celebration of the Olympic Games, seeing that the Games are carried out in the spirit that inspired their revival, and promoting the development of sports throughout the world. The original committee in 1894 consisted of 14 members and Coubertin.

IOC members are regarded as ambassadors from the committee to their national sports organizations. They are in no sense delegates to the committee and may not accept, from the government of their country or from any organization or individual, any instructions that in any way affect their independence.

The IOC is a permanent organization that elects its own members. Reforms in 1999 set the maximum membership at 115, of whom 70 are individuals, 15 current Olympic athletes, 15 national Olympic committee presidents, and 15 international sports federation presidents. The members are elected to renewable eight-year terms, but they must retire at age 70. Term limits were also applied to future presidents.

International Olympic Committee presidents International Olympic Committee presidentsThe IOC elects its president for a period of eight years, at the end of which the president is eligible for reelection for further periods of four years each. The executive board of 15 members holds periodic meetings with the international federations and national Olympic committees. The IOC as a whole meets annually, and a meeting can be convened at any time that one-third of the members so request.

The awarding of the Olympic Games

The honour of holding the Olympic Games is entrusted to a city, not to a country. The choice of the city lies solely with the IOC. Application to hold the Games is made by the chief authority of the city, with the support of the national government.

Sites of the modern Olympic Games Sites of the modern Olympic GamesApplications must state that no political meetings or demonstrations will be held in the stadium or other sports grounds or in the Olympic Village. Applicants also promise that every competitor shall be given free entry without any discrimination on grounds of religion, colour, or political affiliation. This involves the assurance that the national government will not refuse visas to any of the competitors. At the Montreal Olympics in 1976, however, the Canadian government refused visas to the representatives of Taiwan because they were unwilling to forgo the title of the Republic of China, under which their national Olympic committee had been admitted to the IOC. This Canadian decision, in the opinion of the IOC, did great damage to the Olympic Games, and it was later resolved that any country in which the Games are organized must undertake to strictly observe the rules. It was acknowledged that enforcement would be difficult, and even the use of severe penalties by the IOC might not guarantee elimination of infractions.

Corruption

In December 1998 the sporting world was shocked by allegations of widespread corruption within the IOC (International Olympic Committee). It was charged that IOC members had accepted bribes (bribery)—in the form of cash, gifts, entertainment, business favours, travel expenses, medical expenses, and even college tuition for members' children—from members of the committee that had successfully advanced the bid of Salt Lake City, Utah, as the site for the 2002 Winter Games. Accusations of impropriety were also alleged in the conduct of several previous bid committees. The IOC responded by expelling six committee members; several others resigned. In December 1999 an IOC commission announced a 50-point reform package covering the selection and conduct of the IOC members, the bid process, the transparency of financial dealings, the size and conduct of the Games, and drug regulation. The reform package also contained a number of provisions regulating the site-selection process and clarifying the obligations of the IOC, the bid cities, and the national Olympic committees. An independent IOC Ethics Commission also was established.

Political pressures

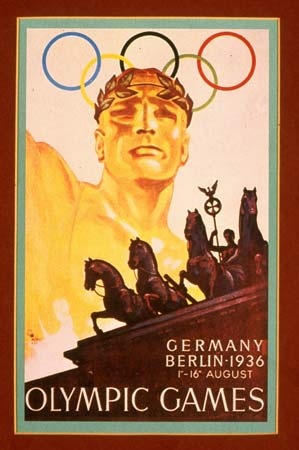

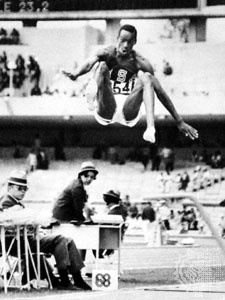

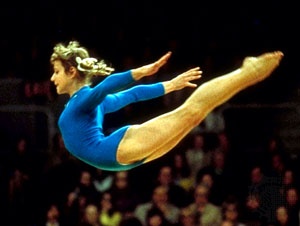

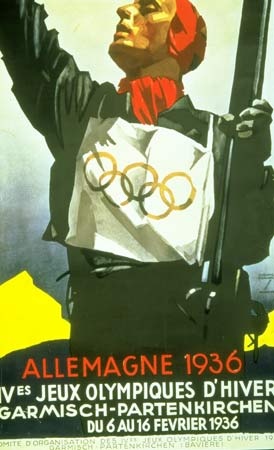

Because the Olympics take place on an international stage, it is not surprising that they have been plagued by the nationalism, manipulation, and propaganda associated with world politics. Attempts to politicize the Olympics were evident as early as the first modern Games at Athens in 1896, when the British compelled an Australian athlete to declare himself British. Other prominent examples of the politicization of the Games include the Nazi propaganda that pervaded the Berlin Games of 1936; the Soviet-Hungarian friction at the 1956 Games in Melbourne, Australia, which followed shortly after the U.S.S.R. had brutally suppressed a revolution in Hungary that year; the forbidden, unofficial, but prominent contests for “points” (medals counts) between the United States and the Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War; the controversy between China and Taiwan leading up to the 1976 Montreal Games; the manifold disputes resulting from South Africa's apartheid policy from 1968 to 1988; the U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games (in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979), followed by the retaliatory boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Games by the Soviet bloc; and, worst of all, the murder of Israeli athletes by terrorists at the 1972 Games in Munich, West Germany.

Even national politics has affected the Games, most notably in 1968 in Mexico City, where, shortly before the Games opened, Mexican troops fired upon Mexican students (killing hundreds) who were protesting government expenditures on the Olympics while the country had pressing social problems. Political tension within the United States also boiled to the top at Mexico City when African American athletes either boycotted the Games or staged demonstrations to protest continuing racism at home.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the IOC sought to more actively promote peace through sports. The IOC and relevant Olympic organizing committees worked with political leaders to allow the participation of former Yugoslav republics at the 1992 Games in Barcelona, Spain, as well as the participation of East Timorese and Palestinian athletes at the 2000 Games in Sydney, Australia. In 2000 the IOC revived and modernized the ancient Olympic truce, making it the focal point of its peace initiatives. (See Sidebar: The Olympic Truce.)

Commercialization

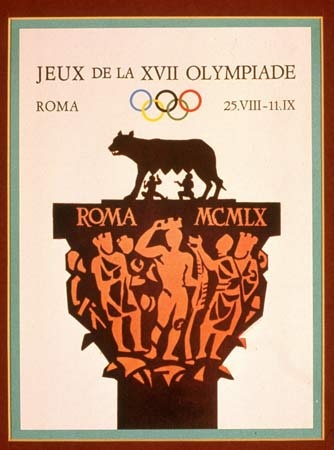

Commercialism has never been wholly absent from the Games, but two large industries have eclipsed all others—namely, television and makers of sports apparel, especially shoes. The IOC, organizing committees of the Olympic Games (OCOGs), and to some degree the international sport federations depend heavily on television revenues, and many of the best athletes depend on money from apparel endorsements. Vigorous bidding for the television rights began in earnest before the Rome Games in 1960; what have been called the “sneaker wars” started an Olympiad later in Tokyo.

The Los Angeles Games of 1984, however, ushered in a new Olympic era. In view of Montreal's huge financial losses from the 1976 Olympics, Peter Ueberroth, head of the Los Angeles OCOG, sold exclusive “official sponsor” rights to the highest bidder in a variety of corporate categories. Now almost everything is commercialized with “official” items ranging from credit cards to beer. And while American decathlete Bill Toomey lost his Olympic eligibility in 1964 for endorsing a nutritional supplement, now athletes openly endorse allergy medicines and blue jeans.

National Olympic committees, international federations, and organizing committees

Each country that desires to participate in the Olympic Games must have a national Olympic committee accepted by the IOC. By the early 21st century, there were more than 200 such committees.

A national Olympic committee (NOC) must be composed of at least five national sporting federations, each affiliated with an appropriate international federation. The ostensible purpose of these NOCs is the development and promotion of the Olympic movement. NOCs arrange to equip, transport, and house their country's representatives at the Olympic Games. According to the rules of the NOCs, they must be not-for-profit organizations, must not associate themselves with affairs of a political or commercial nature, and must be completely independent and autonomous as well as in a position to resist all political, religious, or commercial pressure.

For each Olympic sport there must be an international federation (IF), to which a requisite number of applicable national governing bodies must belong. The IFs promote and regulate their sport on an international level. Since 1986 they have been responsible for determining all questions of Olympic eligibility and competition in their sport. The International Federation of Rowing Associations was founded in 1892, even before the IOC. In 1912 Sigfrid Edström, later president of the IOC, founded the IF for athletics (track and field), the earliest of Olympic sports and perhaps the Games' special focus. Because such sports as football (soccer) and basketball attract great numbers of participants and spectators in all parts of the world, their respective IFs possess great power and sometimes exercise it.

When the IOC awards the Olympic Games to a city, an organizing committee for the Olympic Games (OCOG) replaces the successful bid committee, often including many of that committee's members. Although the IOC retains ultimate authority over all aspects of an Olympiad, the local OCOG has full responsibility for the festival, including finance, facilities, staffing, and accommodations.

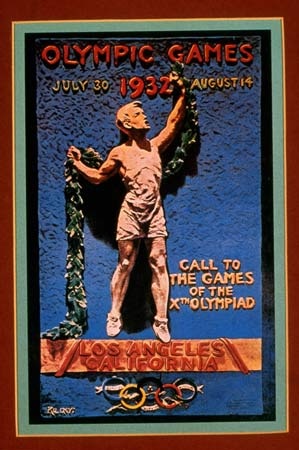

In Paris in 1924, a number of cabins were built near the stadium to house visiting athletes; the complex was called “Olympic Village.” But the first Olympic Village with kitchens, dining rooms, and other amenities was introduced at Los Angeles in 1932. Now each organizing committee provides such a village so that competitors and team officials can be housed together and fed at a reasonable price. Menus for each team are prepared in accord with its own national cuisine. Today, with so many athletes and venues, OCOGs may need to provide more than one village. The villages are located as close as possible to the main stadium and other venues and have separate accommodations for men and women. Only competitors and officials may live in the village, and the number of team officials is limited.

Programs and participation

The Olympic Games celebrate an Olympiad, or period of four years. The first Olympiad of modern times was celebrated in 1896, and subsequent Olympiads are numbered consecutively, even when no Games take place (as was the case in 1916, 1940, and 1944).

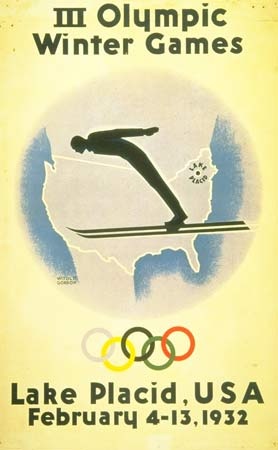

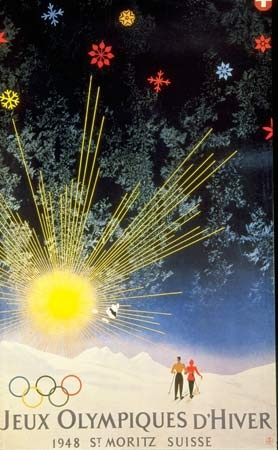

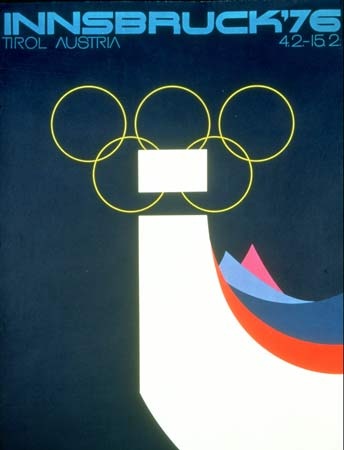

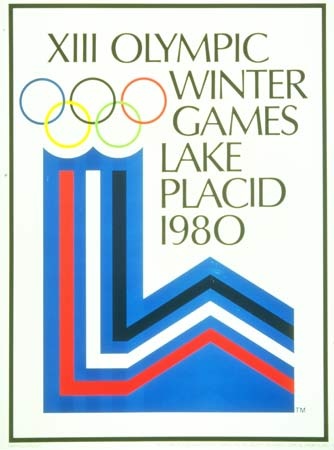

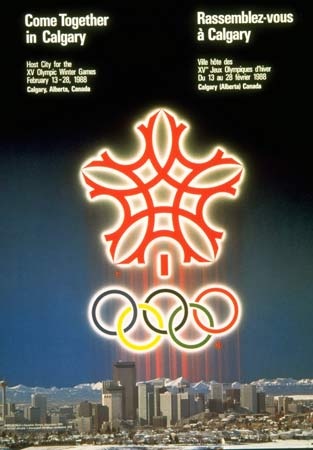

Olympic Winter Games have been held separately from the Games of the Olympiad (Summer Games) since 1924 and were initially held in the same year. In 1986 the IOC voted to alternate the Winter and Summer Games every two years, beginning in 1994. The Winter Games were held in 1992 and again in 1994 and thereafter every four years; the Summer Games maintained their original four-year cycle.

The maximum number of entries permitted for individual events is three per country. The number is fixed (but can be varied) by the IOC in consultation with the international federation concerned. In most team events only one team per country is allowed. In general, an NOC may enter only a citizen of the country concerned. There is no age limit for competitors unless one has been established by a sport's international federation. No discrimination is allowed on grounds of “race,” religion, or political affiliation. The Games are contests between individuals and not between countries.

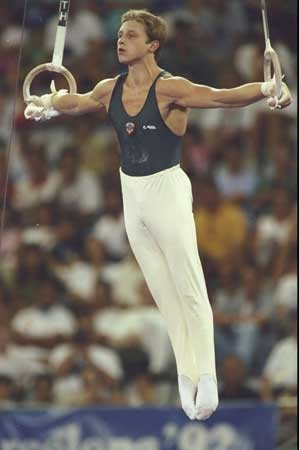

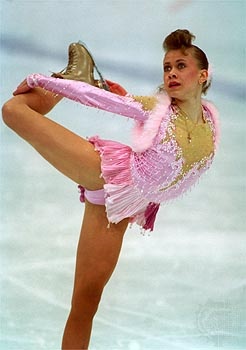

The Summer Olympic program includes the following sports: aquatics (including swimming, synchronized swimming, diving, and water polo), archery, athletics (track and field), badminton, baseball, basketball, boxing, canoeing and kayaking, cycling, equestrian sports, fencing, field hockey, football (soccer), gymnastics, team handball, judo, modern pentathlon, rowing, sailing (formerly yachting), shooting, softball, table tennis, tae kwon do, tennis, triathlon, volleyball, weightlifting, and wrestling. Women participate in all these sports except baseball and boxing. Men do not compete in softball and synchronized swimming. The Winter Olympic program includes sports played on snow or ice: biathlon, bobsledding, curling, ice hockey, ice skating (figure skating and speed skating), luge, skeleton (headfirst) sledding, skiing, ski jumping, and snowboarding. Athletes of either gender may compete in all these sports. An Olympic program must include national exhibitions and demonstrations of fine arts (architecture, literature, music, painting, sculpture, photography, and sports philately).

The particular events included in the different sports are a matter for agreement between the IOC and the international federations. In 2005 the IOC reviewed the summer sports program, and members voted to drop baseball and softball from the 2012 Games. While sports such as rugby and karate were considered, none won the 75 percent favourable vote needed for inclusion.

To be allowed to compete, an athlete must meet the eligibility requirements as defined by the international body of the particular sport and also by the rules of the IOC.

Amateurism versus professionalism

In the final decades of the 20th century there was a shift in policy away from the IOC's traditionally strict definition of amateur status. In 1971 the IOC decided to eliminate the term amateur from the Olympic Charter. Subsequently the eligibility rules were amended to permit “broken-time” payments to compensate athletes for time spent away from work during training and competition. The IOC also legitimized the sponsorship of athletes by NOCs, sports organizations, and private businesses. In 1984 some of the world's best athletes were still banned from the Games because they competed for money, but in 1986 the IOC adopted rules that permit the international federation governing each Olympic sport to decide whether to permit professional athletes in Olympic competition. Professionals in ice hockey, tennis, soccer, and equestrian sports were permitted to compete in the 1988 Olympics, although their eligibility was subject to some restrictions. By the 21st century the presence of professional athletes at the Olympic Games was common.

Doping and drug testing

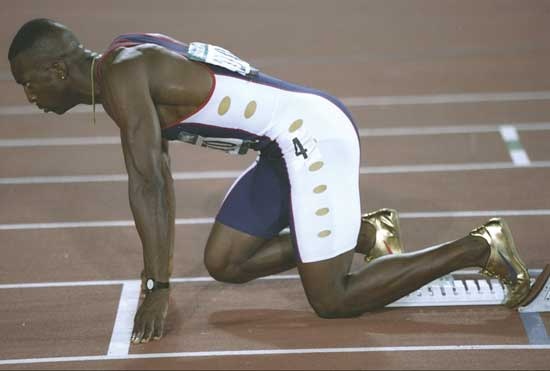

At the 1960 Rome Olympics, a Danish cyclist collapsed and died after his coach had given him amphetamines. Formal drug tests seemed necessary and were instituted at the 1968 Winter Games in Grenoble, France. There only one athlete was disqualified for taking a banned substance—beer. But in the 1970s and ′80s athletes tested positive for a variety of performance-enhancing drugs, and since the ′70s doping has remained the most difficult challenge facing the Olympic movement. As the fame and potential monetary gains for Olympic champions grew in the latter half of the 20th century, so too did the use of performance-enhancing drugs. Tests for anabolic steroids (anabolic steroid) and other substances improved, but so did doping practices, with the design of new substances often a year or two ahead of the new tests. When 100-metre-sprint champion Ben Johnson of Canada tested positive for the drug stanozolol at the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul, South Korea, the world was shocked, and the Games themselves were tainted. To more effectively police doping practices, the IOC formed the World Anti-Doping Agency in 1999. There is now a long list of banned substances and a thorough testing process. Blood and urine samples are collected from athletes before and after competition and sent to a lab for testing. Positive tests for banned substances lead to disqualification, and athletes may be banned from competition for periods ranging from a year to life. Yet, despite the harsh penalties and threat of public humiliation, athletes continue to test positive for banned substances.

Ritual and symbolism

Olympic ceremonies

The opening ceremony

The form of the opening ceremony is laid down by the IOC in great detail, from the moment when the chief of state of the host country is received by the president of the IOC and the organizing committee at the entrance to the stadium to the end of the proceedings, when the last team files out.

When the head of state has reached the appointed place in the tribune and is greeted with the national anthem, the parade of competitors begins. The Greek team is always the first to enter the stadium, and, except for the host team, which is always last, the other countries follow in alphabetical order as determined by the language of the organizing country. Each contingent, dressed in its official uniform, is preceded by a shield with the name of its country, while an athlete carries its national flag. At the 1980 Games, some of the countries protesting the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)'s invasion of Afghanistan the previous year carried the Olympic flag in place of their national flag, in deference to a boycott of those Games by other countries. The competitors march around the stadium and then form in groups in the centre facing the tribune.

The president of the OCOG then delivers a brief speech of welcome, followed by another brief speech from the president of the IOC, who asks the chief of state to proclaim the Games open.

A fanfare of trumpets sound as the Olympic flag is slowly raised. The Olympic flame is then carried into the stadium by the last of a series of runners who have brought the torch on a very long journey from Olympia, Greece. The runner circles the track, mounts the steps, and lights the Olympic fire that burns night and day during the Games.

The medal ceremonies

In individual Olympic events, the award for first place is a gold (silver-gilt, with six grams of fine gold) medal, for second place a silver medal, and for third place a bronze medal. Solid gold medals were last given in 1912. The obverse side of the medal awarded in 2004 at Athens was altered for the first time since 1928 to better reflect the Greek origins of both the ancient and modern Games, depicting the goddess Nike flying above a Greek stadium. The reverse side, changed for each Olympiad, often displayed the official emblem of the particular Games. At the 2004 Athens Games, athletes received authentic olive-leaf crowns as well as medals. Diplomas are awarded for fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth places. All competitors and officials receive a commemorative medal.

Medals are presented during the Games at the various venues, usually soon after the conclusion of each event. The competitors who have won the first three places proceed to the rostrum, with the gold medalist in the centre, the silver medalist on his or her right, and the bronze medalist on the left. Each medal, attached to a chain or ribbon, is hung around the neck of the winner by a member of the IOC, and the flags of the countries concerned are raised to the top of the flagpoles while an abbreviated form of the national anthem of the gold medalist is played. The spectators are expected to stand and face the flags, as do the three successful athletes.

The closing ceremony

The closing ceremony takes place after the final event, which at the Summer Games is usually the equestrian Prix des Nations. The president of the IOC calls the youth of the world to assemble again in four years to celebrate the Games of the next Olympiad. A fanfare is sounded, the Olympic fire is extinguished, and, to the strains of the Olympic anthem, the Olympic flag is lowered and the Games are over. But the festivities do not end there. The 1956 Olympics in Melbourne introduced one of the most important and effective of all Olympic customs. At the suggestion of John Ian Wing, a Chinese teenager living in Australia, the traditional parade of athletes divided into national teams was discarded, allowing athletes to mingle, many hand in hand, as they move around the stadium. This informal parade of athletes without distinction of nationality signifies the friendly bonds of Olympic sports and helps to foster a party atmosphere in the stadium.

Olympic symbols

The flag

In the stadium and its immediate surroundings, the Olympic flag (Olympic Games, flag of the) is flown freely together with the flags of the participating countries. The Olympic flag presented by Coubertin in 1914 is the prototype: it has a white background, and in the centre there are five interlaced rings—blue, yellow, black, green, and red. The blue ring is farthest left, nearest the pole. These rings represent the “five parts of the world” joined together in the Olympic movement.

The motto

In the 19th century, sporting organizations regularly chose a distinctive motto. As the official motto of the Olympic Games, Coubertin adopted “Citius, altius, fortius,” Latin for “Faster, higher, stronger,” a phrase apparently coined by his friend Henri Didon, a friar, teacher, and athletics enthusiast. Some people are now wary of this motto, fearing that it may be misinterpreted as a validation of performance-enhancing drugs. Equally well known is the saying known as the “credo”: “The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not to win but to participate.” Coubertin made that statement on a day when the British and Americans were bitterly disputing who had won the 400-metre race at the 1908 London Games. Although Coubertin attributed the words to Ethelbert Talbot, an American bishop, recent research suggests that the words are Coubertin's own, that he tactfully cited Talbot so as not to appear to admonish personally his English-speaking friends.

The flame and torch relay

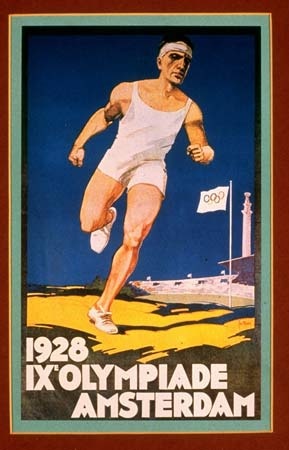

Contrary to popular belief, the torch relay from the temple of Hera in Olympia to the host city has no predecessor or parallel in antiquity. No relay was needed to run the torch from Olympia to Olympia. A perpetual fire was indeed maintained in Hera's temple, but it had no role in the ancient Games. The Olympic flame first appeared at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam. The torch relay was the idea of Carl Diem, organizer of the 1936 Berlin Games, where the relay made its debut. Subsequent editions have grown larger and larger, with more runners, more spectators, and greater distances. The 2004 relay reached all seven continents on its way from Olympia to Athens. The relay is now one of the most splendid and cherished of all Olympic rituals; it emphasizes not only the ancient source of the Olympics but also the internationalism of the modern Games. The flame is now recognized everywhere as an emotionally charged symbol of peace.

Contrary to popular belief, the torch relay from the temple of Hera in Olympia to the host city has no predecessor or parallel in antiquity. No relay was needed to run the torch from Olympia to Olympia. A perpetual fire was indeed maintained in Hera's temple, but it had no role in the ancient Games. The Olympic flame first appeared at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam. The torch relay was the idea of Carl Diem, organizer of the 1936 Berlin Games, where the relay made its debut. Subsequent editions have grown larger and larger, with more runners, more spectators, and greater distances. The 2004 relay reached all seven continents on its way from Olympia to Athens. The relay is now one of the most splendid and cherished of all Olympic rituals; it emphasizes not only the ancient source of the Olympics but also the internationalism of the modern Games. The flame is now recognized everywhere as an emotionally charged symbol of peace.Mascots

The organizers of the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France, devised as an emblem of their Games a cartoonlike figure of a skiing man and called him Schuss. The 1972 Games in Munich, West Germany, adopted the idea and produced the first “official mascot,” a dachshund named Waldi who appeared on related publications and memorabilia. Since then each edition of the Olympic Games has had its own distinctive mascot, sometimes more than one. Typically the mascot is derived from characters or animals especially associated with the host country. Thus, Moscow chose a bear, Norway two figures from Norwegian mythology, and Sydney three animals native to Australia. The strangest mascot was Whatizit, or Izzy, of the 1996 Games in Atlanta, Georgia, a rather amorphous “abstract fantasy figure.” His name comes from people asking “What is it?” He gained more features as the months went by, but his uncertain character and origins contrast strongly with the Athena and Phoebus (Apollo) of the Athens Games of 2004, based on figurines of those gods that were more than 2,500 years old.

History of the modern Summer Games

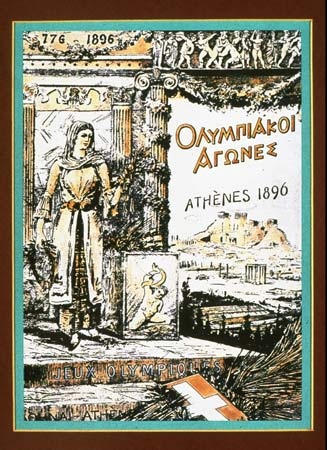

Athens, Greece, 1896

The inaugural Games of the modern Olympics were attended by as many as 280 athletes, all male, coming from 12 countries. The athletes competed in 43 events covering athletics (track and field), cycling, swimming, gymnastics, weightlifting, wrestling, fencing, shooting, and tennis. A festive atmosphere prevailed as foreign athletes were greeted with parades and banquets. A crowd estimated at more than 60,000 attended the opening day of competition. Members of the royal family of Greece played an important role in the organization and management of the Games and were regular spectators over the 10 days of the Olympics. Hungary sent the only national team; most of the foreign athletes were well-to-do college students or members of athletic clubs attracted by the novelty of the Olympics.

The inaugural Games of the modern Olympics were attended by as many as 280 athletes, all male, coming from 12 countries. The athletes competed in 43 events covering athletics (track and field), cycling, swimming, gymnastics, weightlifting, wrestling, fencing, shooting, and tennis. A festive atmosphere prevailed as foreign athletes were greeted with parades and banquets. A crowd estimated at more than 60,000 attended the opening day of competition. Members of the royal family of Greece played an important role in the organization and management of the Games and were regular spectators over the 10 days of the Olympics. Hungary sent the only national team; most of the foreign athletes were well-to-do college students or members of athletic clubs attracted by the novelty of the Olympics.The track-and-field events were held at the Panathenaic Stadium. The stadium, originally built in 330 BC, had been excavated but not rebuilt for the 1870 Greek Olympics and lay in disrepair before the 1896 Olympics, but through the direction and financial aid of Georgios Averoff, a wealthy Egyptian Greek, it was restored with white marble. The ancient track had an unusually elongated shape with such sharp turns that runners were forced to slow down considerably in order to stay in their lanes. The track-and-field competition was dominated by athletes from the United States, who won 9 of the 12 events. The swimming events were held in the cold currents of the Bay of Zea. Two of the four swimming races were won by Alfréd Hajós (Hajós, Alfréd) of Hungary. Paul Masson of France won three of the six cycling events.

The 1896 Olympics featured the first marathon. The race, conceived by Frenchman Michel Bréal, followed the legendary route of Pheidippides, a trained runner who was believed to have been sent from the plain of Marathon to Athens to announce the defeat of an invading Persian army in 490 BC. The race became the highlight of the Games and was won by Spyridon Louis (Louis, Spyridon), a Greek whose victory earned him the lasting admiration of his nation.

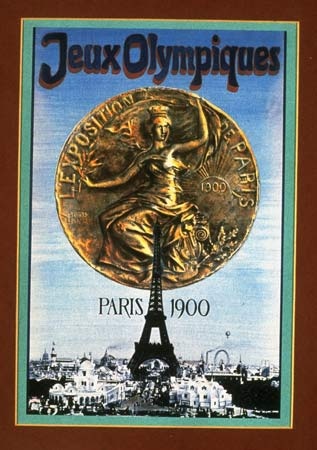

Paris, France, 1900

The second modern Olympic competition was relegated to a sideshow of the World Exhibition, which was being held in Paris in the summer of 1900. Pierre, baron de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics and president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), lost control of his hometown Games to the French government. The Games suffered from poor organization and marketing, with events conducted over a period of five months in venues that often were inadequate. The track-and-field events were held on a grass field that was uneven and often wet. Broken telephone poles were used to make hurdles, and hammer throwers occasionally found their efforts stuck in a tree. The swimming events were contested in the Seine River, whose strong current carried athletes to unrealistically fast times. There was such confusion about schedules that few spectators or journalists were present at the events. Officials and athletes often were unaware that they were participating in the Olympics. See Sidebar: Margaret Abbott: A Study Break.

The second modern Olympic competition was relegated to a sideshow of the World Exhibition, which was being held in Paris in the summer of 1900. Pierre, baron de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics and president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), lost control of his hometown Games to the French government. The Games suffered from poor organization and marketing, with events conducted over a period of five months in venues that often were inadequate. The track-and-field events were held on a grass field that was uneven and often wet. Broken telephone poles were used to make hurdles, and hammer throwers occasionally found their efforts stuck in a tree. The swimming events were contested in the Seine River, whose strong current carried athletes to unrealistically fast times. There was such confusion about schedules that few spectators or journalists were present at the events. Officials and athletes often were unaware that they were participating in the Olympics. See Sidebar: Margaret Abbott: A Study Break.Nevertheless, the Games were attended by nearly 1,000 athletes representing 24 countries. There was an infusion of new events, some of which were not officially part of the Olympic program or were later discontinued (e.g., golf, rugby, cricket, and croquet). Archery, football (soccer), rowing, and equestrian events were among those introduced at the 1900 Games. Women, competing in sailing, lawn tennis, and golf, participated in the Olympics for the first time even though women's events were not officially approved by the IOC. The confusion surrounding the events led to similar confusion over who was the first woman to win an Olympic gold medal; Swiss yachtswoman Hélène de Pourtalés, tennis player Charlotte Cooper of Great Britain, and golfer Margaret Abbott of the United States could all lay claim to that honour.

Despite the problems of the Paris Games, the quality of athletic performance improved. Athletes from the United States, led by jumper Ray Ewry (Ewry, Ray C.) and sprinter Alvin Kraenzlein (Kraenzlein, Alvin), again dominated the track-and-field competition. American athletes won 17 of the 23 track-and-field events, while French athletes earned more than 100 medals, by far the most for any nation at the 1900 Games.

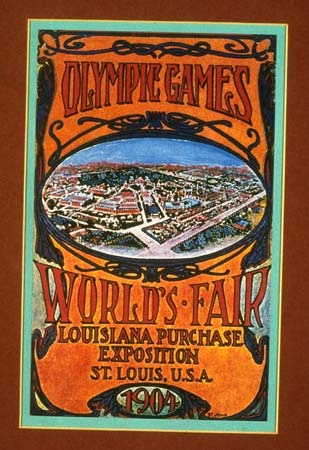

St. Louis, Missouri, U.S., 1904

Like the 1900 Olympics in Paris, the 1904 Games took a secondary role. The Games originally were scheduled for Chicago, but the location was changed to St. Louis when Olympic organizing committee officials decided to combine the Olympics with the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, a large fair celebrating the 100th anniversary of the U.S. acquisition of the Louisiana Territory. As a result, the Games suffered. Several events became part of an “anthropological” exhibition in which American Indians, Pygmies, and other “tribal” peoples competed in events such as mud fighting and pole climbing. The Games were poorly attended by both spectators and athletes. The remoteness of St. Louis and growing tension in Europe over the Russo-Japanese War kept away many of the world's best athletes. Of the approximately 650 competitors representing 12 countries, fewer than 100 were from outside the United States, and about half of those were from Canada. Even the Olympic founder, the baron de Coubertin, stayed away in 1904.

Like the 1900 Olympics in Paris, the 1904 Games took a secondary role. The Games originally were scheduled for Chicago, but the location was changed to St. Louis when Olympic organizing committee officials decided to combine the Olympics with the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, a large fair celebrating the 100th anniversary of the U.S. acquisition of the Louisiana Territory. As a result, the Games suffered. Several events became part of an “anthropological” exhibition in which American Indians, Pygmies, and other “tribal” peoples competed in events such as mud fighting and pole climbing. The Games were poorly attended by both spectators and athletes. The remoteness of St. Louis and growing tension in Europe over the Russo-Japanese War kept away many of the world's best athletes. Of the approximately 650 competitors representing 12 countries, fewer than 100 were from outside the United States, and about half of those were from Canada. Even the Olympic founder, the baron de Coubertin, stayed away in 1904.The overall results were predictably lopsided, with Americans earning more than three-fourths of the 95 gold medals and more than 230 medals in all. The track-and-field events, held on the campus of Washington University, featured Ray Ewry (Ewry, Ray C.), who repeated his Paris performance by winning gold medals in all three standing-jump events. American athletes Archie Hahn (Hahn, Archie), Jim Lightbody (Lightbody, Jim), and Harry Hillman each won three gold medals as well. Thomas Kiely of Ireland, who paid his own fare to the Games rather than compete under the British flag, won the gold medal in an early version of the decathlon. Kiely and his competitors performed the 100-yard sprint, shot put, high jump, 880-yard walk, hammer throw, pole vault, 120-yard hurdles, 56-pound weight throw, long jump, and mile run, all in a single day. The swimming events took place in an artificial lake on the fairgrounds. Zoltán Halmay (Halmay, Zoltán) of Hungary and Charles Daniels (Daniels, Charles) of the United States each won two gold medals in individual swimming, while Emil Rausch of Germany won three. boxing made its Olympic debut in 1904.

Athens, Greece, 1906

When Athens served as host of its second International Olympic Games, in 1906, more events were held and more countries participated than in the first three modern Games. With better athletes and more of them, the competition was fierce and entertaining, resulting in the most satisfying Olympics to date. As in the previous Games, Americans dominated the athletic competition, led once again by standing jumper Ray Ewry and thrower Martin Sheridan (Sheridan, Martin). Both had won in St. Louis and would repeat their victories in London. William Sherring of Canada won an emotionally charged marathon.

The 1906 Games, often referred to as the Intercalated Olympic Games, introduced some important permanent Olympic customs, including the parade of the nations' teams in ranks around the track, now the first major event at all opening ceremonies. Olympic scholars agree that, after the fiascoes of 1900 and 1904, the well-organized and highly successful 1906 Athens Olympics probably saved the entire Olympic movement from an early demise.

These Games, however, are not included in the official IOC lists. The rest of the IOC, over Coubertin's objection, had agreed that Athens would hold Olympics every two years in between the other Olympiads. Coubertin feared more Olympics in Greece would bolster the popular proposal that Athens become the permanent Olympic site. He later “vetoed” the results of the 1906 Games and retroactively withdrew IOC status from them, even though he himself had listed them as official IOC Games in his 1906 Olympic Review. In 1948 the IOC executive board, at Avery Brundage's urging and without discussion, rejected a scholarly petition from another IOC member who sought to reinstate the 1906 Games. In 2003 the IOC executive board once more rejected a carefully argued and well-documented petition from the International Society of Olympic Historians asking that the 1906 Games again be recognized as official. As in 1948, the matter was not even submitted to a vote.

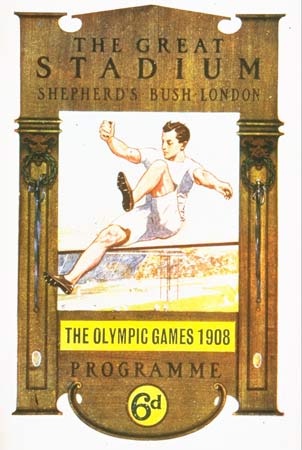

London, England, 1908

The 1908 Olympic Games originally were scheduled for Rome, but, with Italy beset by organizational and financial obstacles, it was decided that the Games should be moved to London. The London Games were the first to be organized by the various sporting bodies concerned and the first to have an opening ceremony. The parade of athletes, like the Games, was marred by politics and controversy. The Finnish team protested Russian rule in Finland. Many Irish athletes refused to compete as subjects of the British crown and were absent from the Games, and a running feud between the Americans and the British began when the American shot-putter Ralph Rose would not dip the U.S. flag in salute to King Edward VII. This refusal later became standard practice for U.S. athletes in the opening parade. (See Sidebar: Ralph Rose and Martin Sheridan: The Battle of Shepherd's Bush.)

The 1908 Olympic Games originally were scheduled for Rome, but, with Italy beset by organizational and financial obstacles, it was decided that the Games should be moved to London. The London Games were the first to be organized by the various sporting bodies concerned and the first to have an opening ceremony. The parade of athletes, like the Games, was marred by politics and controversy. The Finnish team protested Russian rule in Finland. Many Irish athletes refused to compete as subjects of the British crown and were absent from the Games, and a running feud between the Americans and the British began when the American shot-putter Ralph Rose would not dip the U.S. flag in salute to King Edward VII. This refusal later became standard practice for U.S. athletes in the opening parade. (See Sidebar: Ralph Rose and Martin Sheridan: The Battle of Shepherd's Bush.)Twenty-two countries and about 2,000 athletes participated. The opening ceremony and the majority of events were held at Shepherd's Bush Stadium. New events included diving, motorboating, indoor tennis, and field hockey. The track-and-field events were marked by bickering between American athletes and British officials. The 400-metre final was nullified by officials who disqualified the apparent winner, American John Carpenter, for deliberately impeding the path of Wyndham Halswelle of the United Kingdom. A new race was ordered, but the other qualifiers, both American, refused to run. Halswelle then won the gold in the only walkover in Olympic history. See also Sidebar: Dorando Pietri: Falling at the Finish. Henry Taylor (Taylor, Henry) of the United Kingdom starred in the swimming events, winning three gold medals.

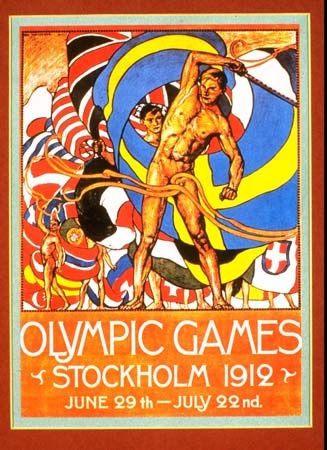

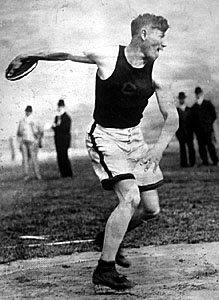

Stockholm, Sweden, 1912

Known as the “Swedish Masterpiece,” the 1912 Olympics were the best organized and most efficiently run Games to that date. Electronic timing devices and a public address system were used for the first time. The Games were attended by approximately 2,400 athletes representing 28 countries. New competition included the modern pentathlon and swimming and diving events for women. The boxing competition was canceled by the Swedish organizers, who found the sport disagreeable; this cancellation, along with controversial officiating at earlier Olympics, prompted the IOC to greatly curtail the role of local organizing groups after 1912.

Known as the “Swedish Masterpiece,” the 1912 Olympics were the best organized and most efficiently run Games to that date. Electronic timing devices and a public address system were used for the first time. The Games were attended by approximately 2,400 athletes representing 28 countries. New competition included the modern pentathlon and swimming and diving events for women. The boxing competition was canceled by the Swedish organizers, who found the sport disagreeable; this cancellation, along with controversial officiating at earlier Olympics, prompted the IOC to greatly curtail the role of local organizing groups after 1912. The star of the 1912 Olympics was American Jim Thorpe (Thorpe, Jim). Entered in four events, he began slowly with a fourth-place finish in the high jump and a seventh-place finish in the long jump. In the pentathlon and decathlon, however, Thorpe dominated the events to win two gold medals. The track-and-field competition also featured the long-distance running of Hannes Kolehmainen (Kolehmainen, Hannes) of Finland, who won gold medals in the 5,000- and 10,000-metre runs and the 12,000-metre cross-country race. The 1912 Games marked the Olympic debuts of legendary fencer Nedo Nadi (Nadi brothers) of Italy and American swimmer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku (Kahanamoku, Duke Paoa) of Hawaii.

The star of the 1912 Olympics was American Jim Thorpe (Thorpe, Jim). Entered in four events, he began slowly with a fourth-place finish in the high jump and a seventh-place finish in the long jump. In the pentathlon and decathlon, however, Thorpe dominated the events to win two gold medals. The track-and-field competition also featured the long-distance running of Hannes Kolehmainen (Kolehmainen, Hannes) of Finland, who won gold medals in the 5,000- and 10,000-metre runs and the 12,000-metre cross-country race. The 1912 Games marked the Olympic debuts of legendary fencer Nedo Nadi (Nadi brothers) of Italy and American swimmer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku (Kahanamoku, Duke Paoa) of Hawaii.The 1916 Games, scheduled for Berlin, were canceled because of the outbreak of World War I.

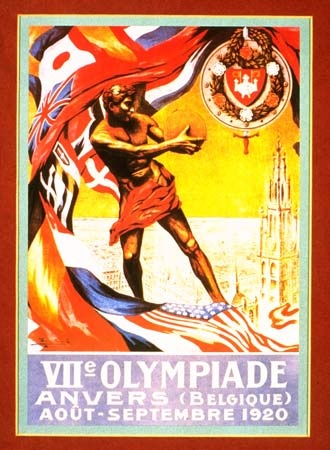

Antwerp, Belgium, 1920

The 1920 Olympics were awarded to Antwerp in hopes of bringing a spirit of renewal to Belgium, which had been devastated during the war. The defeated countries of World War I—Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey—were not invited. The new Soviet Union chose not to attend.

The 1920 Olympics were awarded to Antwerp in hopes of bringing a spirit of renewal to Belgium, which had been devastated during the war. The defeated countries of World War I—Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey—were not invited. The new Soviet Union chose not to attend.The city, plagued by bad weather and economic woes, had a very short time to clean up the rubble left by the war and construct new facilities for the Games. The athletics stadium was unfinished when the Games began, and athletes were housed in crowded rooms furnished with folding cots. The events were lightly attended, as few could afford tickets. In the final days, the stands were filled with schoolchildren who were given free admittance.

The Olympic flag (Olympic Games, flag of the) was introduced at the Antwerp Games. More than 2,600 athletes (including more than 60 women) participated in the Games, representing 29 countries. The highlight of the track-and-field competition was the running of Paavo Nurmi (Nurmi, Paavo) of Finland, who battled Joseph Guillemot of France and won three of his nine career gold medals in the 10,000-metre run, the 10,000-metre cross-country individual race, and the cross-country team race. In the 5,000-metre run he finished second to Guillemot (see Sidebar: Joseph Guillemot: Life After War). The Finnish team gave a historic performance, gaining nine gold medals in athletics, one fewer than the U.S. team, which had traditionally dominated the sport.

Italian fencer Nedo Nadi (Nadi brothers) won five gold medals, including individual titles in foil and sabre. The swimming and diving events starred Americans Duke Paoa Kahanamoku (Kahanamoku, Duke Paoa) (two golds), Ethelda Bleibtrey (Bleibtrey, Ethelda) (three golds), and Aileen Riggin (Riggin, Aileen), who at age 14 won the gold medal in springboard diving.

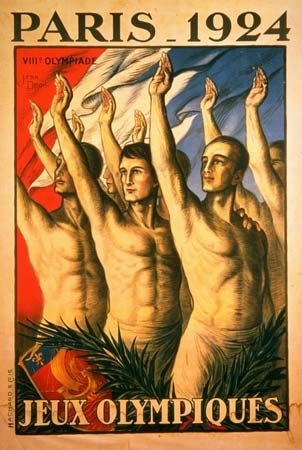

Paris, France, 1924

The 1924 Games represented a coming of age for the Olympics. Held in Paris in tribute to the baron de Coubertin, the retiring president of the IOC and founder of the Olympic movement, the Games featured a high calibre of competition. International federations had gained more influence over their respective sports, standardizing the rules of competition, and national Olympic organizations in most countries conducted trials to ensure that the best athletes were sent to compete. More than 3,000 athletes, including more than 100 women, represented a record 44 countries. fencing was added to the women's events, although the total number of events decreased because of a reduction in the number of shooting and yachting competitions.

The 1924 Games represented a coming of age for the Olympics. Held in Paris in tribute to the baron de Coubertin, the retiring president of the IOC and founder of the Olympic movement, the Games featured a high calibre of competition. International federations had gained more influence over their respective sports, standardizing the rules of competition, and national Olympic organizations in most countries conducted trials to ensure that the best athletes were sent to compete. More than 3,000 athletes, including more than 100 women, represented a record 44 countries. fencing was added to the women's events, although the total number of events decreased because of a reduction in the number of shooting and yachting competitions.The Finnish team, led by Paavo Nurmi (Nurmi, Paavo) and Ville Ritola (Ritola, Ville), ruled the distance running races. For the first time, the swimming competition attracted as much attention as track-and-field. The men's events featured a rare collection of talent, including the Kahanamoku (Kahanamoku, Duke Paoa) brothers and Clarence (“Buster”) Crabbe (Crabbe, Buster) of the United States, Andrew (“Boy”) Charlton (Charlton, Boy) of Australia, Yoshiyuki Tsuruta of Japan, and Arne Borg (Borg, Arne) of Sweden. The star of the competition, however, was American Johnny Weissmuller (Weissmuller, Johnny), who won three gold medals as well as a bronze medal as a member of the water polo team. See also Sidebar: Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams: Chariots of Fire.

Helen Wills (Wills, Helen) of the United States won gold medals in the singles and doubles tennis events. After the 1924 Games, tennis was dropped from Olympic competition because of questions over the amateur standing of many participants. The sport did not return to the Olympics until 1988.

Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1928

Track-and-field and gymnastics events were added to the women's slate at the 1928 Olympics. There was much criticism of the decision, led by the baron de Coubertin and the Vatican. Women athletes, however, had formed their own track organizations and had held an Olympic-style women's competition in 1922 and 1926. Their performances at these events convinced the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF; later International Association of Athletics Federations) that women were capable of a high level of athletic competition and deserved a place at the Olympics.

Track-and-field and gymnastics events were added to the women's slate at the 1928 Olympics. There was much criticism of the decision, led by the baron de Coubertin and the Vatican. Women athletes, however, had formed their own track organizations and had held an Olympic-style women's competition in 1922 and 1926. Their performances at these events convinced the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF; later International Association of Athletics Federations) that women were capable of a high level of athletic competition and deserved a place at the Olympics. Germany returned to Olympic competition at the 1928 Games, which featured the debut of the Olympic flame. Approximately 3,000 athletes (including nearly 300 women), representing 46 countries, participated in the Olympics. The men's athletics competition was noteworthy for two reasons. It was last Olympic Games for the great Paavo Nurmi (Nurmi, Paavo) and Ville Ritola (Ritola, Ville) of Finland. It was also the poorest performance to date for the U.S. team, which won only three of a possible 12 gold medals in running events. Percy Williams (Williams, Percy) of Canada won both the 100- and 200-metre runs. Controversy arose in the women's 800-metre run when several women collapsed from exhaustion at the end of the race; Olympic officials concluded that the distance was too long for women, and it was not until the 1960 Games in Rome that women were allowed to compete in a race of more than 200 metres.

Germany returned to Olympic competition at the 1928 Games, which featured the debut of the Olympic flame. Approximately 3,000 athletes (including nearly 300 women), representing 46 countries, participated in the Olympics. The men's athletics competition was noteworthy for two reasons. It was last Olympic Games for the great Paavo Nurmi (Nurmi, Paavo) and Ville Ritola (Ritola, Ville) of Finland. It was also the poorest performance to date for the U.S. team, which won only three of a possible 12 gold medals in running events. Percy Williams (Williams, Percy) of Canada won both the 100- and 200-metre runs. Controversy arose in the women's 800-metre run when several women collapsed from exhaustion at the end of the race; Olympic officials concluded that the distance was too long for women, and it was not until the 1960 Games in Rome that women were allowed to compete in a race of more than 200 metres.The Japanese team won the most medals in the swimming competition. Johnny Weissmuller (Weissmuller, Johnny) of the United States concluded his Olympic career with gold medals in the 100-metre freestyle swim and the 800-metre freestyle relay. The Hungarian sabre team won the first of seven consecutive gold medals.

Los Angeles, California, U.S., 1932

Only about 1,300 athletes, representing 37 countries, competed in the 1932 Games. The poor participation was the result of the worldwide economic depression (Great Depression) and the expense of traveling to California. The Los Angeles Games featured the first Olympic Village, which was located in Baldwin Hills, a suburb of Los Angeles, and covered 321 acres (130 hectares). The male athletes were housed in more than 500 bungalows and had access to a hospital, a library, a post office, and 40 kitchens serving a variety of cuisines. The female athletes stayed at a downtown hotel. The Los Angeles Coliseum was expanded to seat more than 100,000 people, and a new track was installed. Made of crushed peat, the new surface was exceptionally fast, resulting in 10 world records in the running events. Uniform automatic timing and the photo-finish camera were used for the first time at the 1932 Games.

Only about 1,300 athletes, representing 37 countries, competed in the 1932 Games. The poor participation was the result of the worldwide economic depression (Great Depression) and the expense of traveling to California. The Los Angeles Games featured the first Olympic Village, which was located in Baldwin Hills, a suburb of Los Angeles, and covered 321 acres (130 hectares). The male athletes were housed in more than 500 bungalows and had access to a hospital, a library, a post office, and 40 kitchens serving a variety of cuisines. The female athletes stayed at a downtown hotel. The Los Angeles Coliseum was expanded to seat more than 100,000 people, and a new track was installed. Made of crushed peat, the new surface was exceptionally fast, resulting in 10 world records in the running events. Uniform automatic timing and the photo-finish camera were used for the first time at the 1932 Games.The star of the Games was American Babe Didrikson (Zaharias, Babe Didrikson) (later Zaharias). She had won five events at the U.S. Olympic trials, but Olympic rules allowed women to compete in no more than three. Didrikson competed in the 80-metre hurdles, javelin, and high jump, winning two gold medals and a silver. The U.S. team returned to its dominance of the track-and-field events, winning 11 gold medals. American Eddie Tolan (Tolan, Eddie) won the 100- and 200-metre runs. The first race-walking event was held at the Los Angeles Games. See also Sidebar: Stanislawa Walasiewicz: The Curious Story of Stella Walsh.

The Japanese swim team, composed almost entirely of teenagers, won five of the six men's events. Kitamura Kusuo, who won the gold medal in the 1,500-metre freestyle at age 14, became the youngest male swimmer ever to win an Olympic event. American women dominated in swimming, taking four of the five gold medals; Helene Madison (Madison, Helene) won gold medals in the 100- and 400-metre freestyle races and earned a third gold as part of the U.S. relay team.

Berlin, Germany, 1936

The 1936 Olympics were held in a tense, politically charged atmosphere. The Nazi Party had risen to power in 1933, two years after Berlin was awarded the Games, and its racist policies led to international debate about a boycott of the Games. Fearing a mass boycott, the IOC pressured the German government and received assurances that qualified Jewish athletes would be part of the German team and that the Games would not be used to promote Nazi ideology. Adolf Hitler (Hitler, Adolf)'s government, however, routinely failed to deliver on such promises. Only one athlete of Jewish descent was a member of the German team (see Sidebar: Helene Mayer: Fencing for the Führer); pamphlets and speeches about the natural superiority of the Aryan race were commonplace; and the Reich Sports Field, a newly constructed sports complex that covered 325 acres (131.5 hectares) and included four stadiums, was draped in Nazi banners and symbols. Nonetheless, the attraction of a spirited sports competition was too great, and in the end 49 countries chose to attend the Olympic Games in Berlin.

The 1936 Olympics were held in a tense, politically charged atmosphere. The Nazi Party had risen to power in 1933, two years after Berlin was awarded the Games, and its racist policies led to international debate about a boycott of the Games. Fearing a mass boycott, the IOC pressured the German government and received assurances that qualified Jewish athletes would be part of the German team and that the Games would not be used to promote Nazi ideology. Adolf Hitler (Hitler, Adolf)'s government, however, routinely failed to deliver on such promises. Only one athlete of Jewish descent was a member of the German team (see Sidebar: Helene Mayer: Fencing for the Führer); pamphlets and speeches about the natural superiority of the Aryan race were commonplace; and the Reich Sports Field, a newly constructed sports complex that covered 325 acres (131.5 hectares) and included four stadiums, was draped in Nazi banners and symbols. Nonetheless, the attraction of a spirited sports competition was too great, and in the end 49 countries chose to attend the Olympic Games in Berlin.The Berlin Olympics also featured advancements in media coverage. It was the first Olympic competition to use telex transmissions of results, and zeppelins (zeppelin) were used to quickly transport newsreel footage to other European cities. The Games were televised for the first time, transmitted by closed circuit to specially equipped theatres in Berlin. The 1936 Games also introduced the torch relay by which the Olympic flame is transported from Greece.

Nearly 4,000 athletes competed in 129 events. The track-and-field competition starred American Jesse Owens (Owens, Jesse), who won three individual gold medals and a fourth as a member of the triumphant U.S. 4 × 100-metre relay team. Altogether Owens and his teammates won 12 men's track-and-field gold medals; the success of Owens and the other African American athletes, referred to as “black auxiliaries” by the Nazi press, was considered a particular blow to Hitler's Aryan ideals. See also Sidebar: Sohn Kee-chung: The Defiant One.

However, the Germans did win the most medals overall, dominating the gymnastics, rowing, and equestrian events. Hendrika (“Rie”) Mastenbroek (Mastenbroek, Hendrika) of The Netherlands won three gold medals and a silver in the swimming competition. basketball, an Olympic event for the first time in 1936, was won by the U.S. team. Canoeing also debuted as an Olympic sport.

The 1940 and 1944 Games, scheduled for Helsinki, Finland (originally slated for Tokyo), and London, respectively, were canceled because of World War II.

London, England, 1948

Despite limited preparation time and after much debate over the need for a sports festival at a time when many countries were still recovering from the destruction of World War II, the 1948 Olympics ultimately were very popular and were perceived as providing relief from the strains caused by the war.

Despite limited preparation time and after much debate over the need for a sports festival at a time when many countries were still recovering from the destruction of World War II, the 1948 Olympics ultimately were very popular and were perceived as providing relief from the strains caused by the war.Germany and Japan, the defeated powers, were not invited to participate. The Soviet Union also did not participate, but the Games were the first to be attended by communist countries, including Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Poland. The London Games lacked the new facilities that had been used in Los Angeles and Berlin, but the British capital's sports facilities had survived the war in good condition and were adequate for Olympic competition. Wembley Stadium hosted the opening ceremonies, the track-and-field competition, and other events. There was no Olympic Village; the male athletes were housed at an army camp in Uxbridge, while the women stayed in dormitories at Southlands College.

Over 4,000 athletes from 59 countries participated in the Games. Poor weather and a sloppy track slowed the track-and-field competition, in which the fewest Olympic records were set in the history of the Games. The women's competition was expanded to 10 events with the addition of the 200-metre run, the long jump, and the shot put. Fanny Blankers-Koen (Blankers-Koen, Fanny), a 30-year-old mother of two children, won four gold medals for The Netherlands. Emil Zátopek (Zátopek, Emil) of Czechoslovakia won the 10,000-metre run, the first of four gold medals in his career. American Bob Mathias (Mathias, Bob) became the youngest gold medalist in the decathlon, winning the event at age 17.

Over 4,000 athletes from 59 countries participated in the Games. Poor weather and a sloppy track slowed the track-and-field competition, in which the fewest Olympic records were set in the history of the Games. The women's competition was expanded to 10 events with the addition of the 200-metre run, the long jump, and the shot put. Fanny Blankers-Koen (Blankers-Koen, Fanny), a 30-year-old mother of two children, won four gold medals for The Netherlands. Emil Zátopek (Zátopek, Emil) of Czechoslovakia won the 10,000-metre run, the first of four gold medals in his career. American Bob Mathias (Mathias, Bob) became the youngest gold medalist in the decathlon, winning the event at age 17.Americans, led by diver Sammy Lee (Lee, Sammy), won every men's swimming and diving event. Victoria Draves (Draves, Victoria) of the United States earned a gold medal in both platform and springboard diving. The 1948 Olympics featured the debuts of several legendary Olympic performers: László Papp (Papp, László) of Hungary won the first of his three gold medals in boxing, Paul Elvstrøm (Elvstrøm, Paul) of Denmark won the first of his four gold medals in yachting, and Gert Fredriksson (Fredriksson, Gert) of Sweden won the first two of his six gold medals in kayaking.

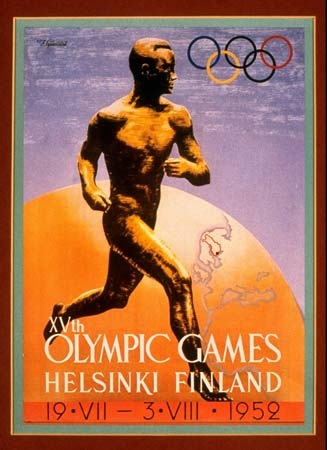

Helsinki, Finland, 1952

The 1952 Games were the first Olympics in which the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) participated (a Russian team had last competed in the 1912 Games), and the international tension caused by the Cold War initially prevailed. Prior to the Games, the U.S. Olympic Committee used the rivalry between East and West to raise funds for the U.S. team. The Soviet Union announced plans to house its athletes in Leningrad and fly into Helsinki each day; these plans were dropped, but a separate Olympic Village for Eastern bloc countries was created in Otaniemi. The Games themselves, however, were friendly, and by the end of the competition Soviet officials had opened their village to all athletes. The Helsinki Games marked the return of German and Japanese teams to Olympic competition. East Germany had applied for participation in the Games but was denied, and the German team consisted of athletes from West Germany only.

The 1952 Games were the first Olympics in which the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) participated (a Russian team had last competed in the 1912 Games), and the international tension caused by the Cold War initially prevailed. Prior to the Games, the U.S. Olympic Committee used the rivalry between East and West to raise funds for the U.S. team. The Soviet Union announced plans to house its athletes in Leningrad and fly into Helsinki each day; these plans were dropped, but a separate Olympic Village for Eastern bloc countries was created in Otaniemi. The Games themselves, however, were friendly, and by the end of the competition Soviet officials had opened their village to all athletes. The Helsinki Games marked the return of German and Japanese teams to Olympic competition. East Germany had applied for participation in the Games but was denied, and the German team consisted of athletes from West Germany only. Nearly 5,000 athletes competed, representing 69 countries. The track-and-field competition starred Emil Zátopek (Zátopek, Emil) of Czechoslovakia, who won the gold medal in the 5,000- and 10,000-metre runs. He also won the gold medal in the marathon, in his first attempt ever at that event. The American men, led by pole vaulter Bob Richards (Richards, Bob) and 800-metre specialist Mal Whitfield (Whitfield, Mal), won 14 of the 23 events. The women's track competition featured the sprinting of Marjorie Jackson (Jackson, Marjorie) and the hurdling of Shirley Strickland de la Hunty (Strickland de la Hunty, Shirley), both of Australia. Soviet women, led by Galina Zybina (Zybina, Galina), made a strong showing in the field events.

Nearly 5,000 athletes competed, representing 69 countries. The track-and-field competition starred Emil Zátopek (Zátopek, Emil) of Czechoslovakia, who won the gold medal in the 5,000- and 10,000-metre runs. He also won the gold medal in the marathon, in his first attempt ever at that event. The American men, led by pole vaulter Bob Richards (Richards, Bob) and 800-metre specialist Mal Whitfield (Whitfield, Mal), won 14 of the 23 events. The women's track competition featured the sprinting of Marjorie Jackson (Jackson, Marjorie) and the hurdling of Shirley Strickland de la Hunty (Strickland de la Hunty, Shirley), both of Australia. Soviet women, led by Galina Zybina (Zybina, Galina), made a strong showing in the field events.The 1952 Olympics also saw the debut of the Soviet gymnast Viktor Chukarin (Chukarin, Viktor Ivanovich), who won the first of his two individual gold medals in the combined exercises. American diver Pat McCormick (McCormick, Pat) won two gold medals. Swedish equestrian Henri St. Cyr (Saint Cyr, Henri) won a gold medal in both the individual and team dressage competitions. See also Sidebar: Lis Hartel: Beating Polio.

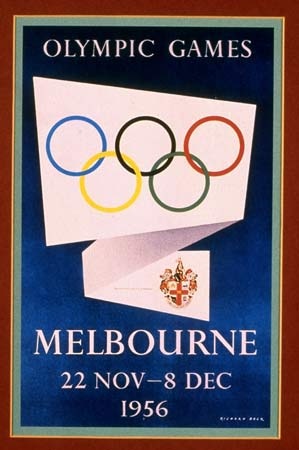

Melbourne, Australia, 1956

The 1956 Olympics were the first held in the Southern Hemisphere. Because of the reversal of seasons, the Games were celebrated in November and December. The remoteness of Australia and two international crises accounted for the low number of participants; fewer than 3,500 athletes from 67 countries attended the Games. Egypt, Lebanon, and Iraq boycotted in protest of the Israeli invasion of the Sinai Peninsula in October. Moreover, a few weeks before the opening of the Games, the Soviet army entered Budapest, Hungary, and suppressed a popular uprising against the government (see also Sidebar: Hungary v. U.S.S.R.: Blood in the Water); The Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland boycotted in protest of the Soviet invasion. East and West Germany competed as a single team, a practice that would last through the 1964 Games. Because of Australian quarantine restrictions, the equestrian events were held in Stockholm during June. The Melbourne Games introduced the practice of athletes marching into the closing ceremonies together, not segregated by nation.

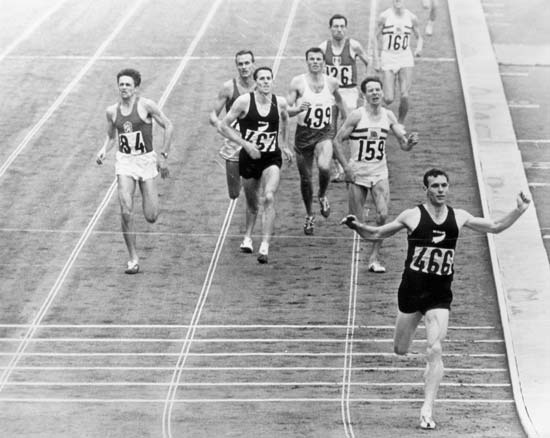

The 1956 Olympics were the first held in the Southern Hemisphere. Because of the reversal of seasons, the Games were celebrated in November and December. The remoteness of Australia and two international crises accounted for the low number of participants; fewer than 3,500 athletes from 67 countries attended the Games. Egypt, Lebanon, and Iraq boycotted in protest of the Israeli invasion of the Sinai Peninsula in October. Moreover, a few weeks before the opening of the Games, the Soviet army entered Budapest, Hungary, and suppressed a popular uprising against the government (see also Sidebar: Hungary v. U.S.S.R.: Blood in the Water); The Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland boycotted in protest of the Soviet invasion. East and West Germany competed as a single team, a practice that would last through the 1964 Games. Because of Australian quarantine restrictions, the equestrian events were held in Stockholm during June. The Melbourne Games introduced the practice of athletes marching into the closing ceremonies together, not segregated by nation.The track-and-field competition was held at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. The U.S. team won 15 of the 24 men's events. Sprinter Bobby Joe Morrow (Morrow, Bobby Joe) earned three gold medals, and Al Oerter (Oerter, Al) won the first of his four consecutive gold medals in the discus. Soviet distance runner Vladimir Kuts (Kuts, Vladimir) won two gold medals. Australian Betty Cuthbert (Cuthbert, Betty) was the star of the women's competition, winning the 100- and 200-metre runs and picking up a third gold medal as a member of the Australian 4 × 100-metre relay team.