apartheid

social policy

(Afrikaans: “apartness”), policy that governed relations between South Africa's white minority and nonwhite majority and sanctioned racial segregation (segregation, racial) and political and economic discrimination (racism) against nonwhites. The implementation of apartheid, often called “separate development” since the 1960s, was made possible through the Population Registration Act of 1950, which classified all South Africans as either Bantu (Bantu peoples) (all black Africans), Coloured (those of mixed race), or white. A fourth category—Asian (Indian and Pakistani)—was later added.

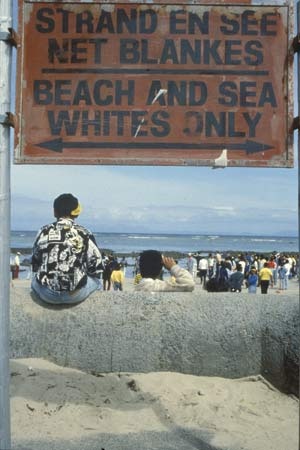

(Afrikaans: “apartness”), policy that governed relations between South Africa's white minority and nonwhite majority and sanctioned racial segregation (segregation, racial) and political and economic discrimination (racism) against nonwhites. The implementation of apartheid, often called “separate development” since the 1960s, was made possible through the Population Registration Act of 1950, which classified all South Africans as either Bantu (Bantu peoples) (all black Africans), Coloured (those of mixed race), or white. A fourth category—Asian (Indian and Pakistani)—was later added. Racial segregation, sanctioned by law, was widely practiced in South Africa before 1948, but the National Party, which gained office that year, extended the policy and gave it the name apartheid. The Group Areas Act of 1950 established residential and business sections in urban areas for each race, and members of other races were barred from living, operating businesses, or owning land in them. In practice this act and two others (1954, 1955), which became known collectively as the Land Acts, completed a process that had begun with similar Land Acts adopted in 1913 and 1936; the end result was to set aside more than 80 percent of South Africa's land for the white minority. To help enforce the segregation of the races and prevent blacks from encroaching on white areas, the government strengthened the existing “pass” laws, which required nonwhites to carry documents authorizing their presence in restricted areas. Other laws forbade most social contacts between the races, authorized segregated public facilities, established separate educational standards, restricted each race to certain types of jobs, curtailed nonwhite labour unions, and denied nonwhite participation (through white representatives) in the national government.

Racial segregation, sanctioned by law, was widely practiced in South Africa before 1948, but the National Party, which gained office that year, extended the policy and gave it the name apartheid. The Group Areas Act of 1950 established residential and business sections in urban areas for each race, and members of other races were barred from living, operating businesses, or owning land in them. In practice this act and two others (1954, 1955), which became known collectively as the Land Acts, completed a process that had begun with similar Land Acts adopted in 1913 and 1936; the end result was to set aside more than 80 percent of South Africa's land for the white minority. To help enforce the segregation of the races and prevent blacks from encroaching on white areas, the government strengthened the existing “pass” laws, which required nonwhites to carry documents authorizing their presence in restricted areas. Other laws forbade most social contacts between the races, authorized segregated public facilities, established separate educational standards, restricted each race to certain types of jobs, curtailed nonwhite labour unions, and denied nonwhite participation (through white representatives) in the national government.Under the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951 the government reestablished tribal organizations for black Africans, and the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 created 10 African homelands, or Bantustans (Bantustan). The Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970 made every black South African, irrespective of actual residence, a citizen of one of the Bantustans, thereby excluding blacks from the South African body politic. Four of the Bantustans were granted independence as republics, and the remaining had varying degrees of self-government; but all remained dependent, both politically and economically, on South Africa. The dependence of the South African economy on nonwhite labour, though, made it difficult for the government to carry out this policy of separate development.

Although the government had the power to suppress virtually all criticism of its policies, there was always some opposition to apartheid within South Africa. Black African groups, with the support of some whites, held demonstrations and strikes, and there were many instances of violent protest and of sabotage. An attempt to enforce Afrikaans language requirements for black African students led to the Soweto riots in 1976. Some white politicians called for the relaxation of minor restrictions, referred to as “petty apartheid,” or for the establishment of racial equality.

Apartheid also received international censure. South Africa was forced to withdraw from the Commonwealth in 1961 when it became apparent that other member countries would not accept its racial policies. In 1985 both the United Kingdom and the United States imposed selective economic sanctions (sanction) on South Africa. In response to these and other pressures, the South African government abolished the “pass” laws in 1986, although blacks were still prohibited from living in designated white areas and the police were granted broad emergency powers.

In a more fundamental shift of policy, however, the government of South African president F.W. de Klerk (de Klerk, F.W.) in 1990–91 repealed most of the social legislation that provided the legal basis for apartheid, including the Population Registration Act. Systematic racial segregation remained deeply entrenched in South African society, though, and continued on a de facto basis. A new constitution that enfranchised blacks and other racial groups was adopted in 1993 and took effect in 1994. All-race national elections, also in 1994, produced a coalition government with a black majority. These developments marked the end of legislated apartheid, though not of its entrenched social and economic effects.