Reagan, Ronald W.

president of United States

Introduction

in full Ronald Wilson Reagan

born February 6, 1911, Tampico, Illinois, U.S.

died June 5, 2004, Los Angeles, California

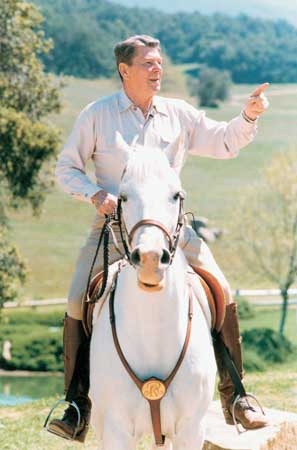

40th president of the United States (1981–89), noted for his conservative Republicanism, his fervent anticommunism, and his appealing personal style, characterized by a jaunty affability and folksy charm. The only movie actor ever to become president, he had a remarkable skill as an orator that earned him the title “the Great Communicator.” His policies have been credited with contributing to the demise of Soviet communism. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)

40th president of the United States (1981–89), noted for his conservative Republicanism, his fervent anticommunism, and his appealing personal style, characterized by a jaunty affability and folksy charm. The only movie actor ever to become president, he had a remarkable skill as an orator that earned him the title “the Great Communicator.” His policies have been credited with contributing to the demise of Soviet communism. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)Early life and acting career

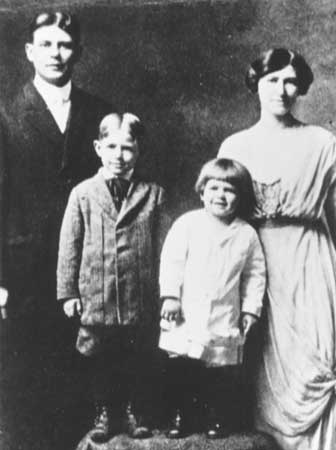

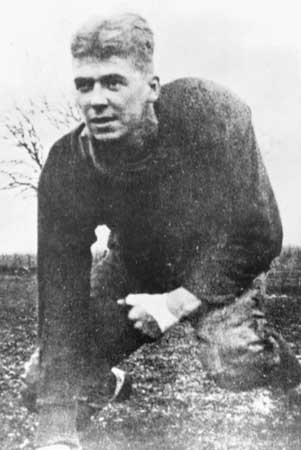

Reagan was the second child of John Edward (“Jack”) Reagan, a struggling shoe salesman, and Nelle Wilson Reagan. Reagan's nickname, “Dutch,” derived from his father's habit of referring to his infant son as his “fat little Dutchman.” After several years of moving from town to town—made necessary in part because of Jack Reagan's alcoholism, which made it difficult for him to hold a job—the family settled in Dixon, Illinois, in 1920. Despite their near poverty and his father's drinking problem, Reagan later recalled his childhood in Dixon as the happiest period of his life. At Eureka College in Eureka, Illinois, Reagan played gridiron football and was active in the drama society but earned only passing grades. A popular student, he was elected class president in his senior year. Graduating in 1932 with a bachelor's degree in economics and sociology, he decided to enter radio broadcasting. He landed a job as a sportscaster at station WOC in Davenport, Iowa, by delivering entirely from memory an exciting play-by-play description of a Eureka College football game. Later he moved to station WHO in Des Moines, where, as sportscaster “Dutch Reagan,” he became popular throughout the state for his broadcasts of Chicago Cubs baseball games. Because the station could not afford to send him to Wrigley Field in Chicago, Reagan was forced to improvise a running account of the games based on sketchy details delivered over a teletype machine.

Reagan was the second child of John Edward (“Jack”) Reagan, a struggling shoe salesman, and Nelle Wilson Reagan. Reagan's nickname, “Dutch,” derived from his father's habit of referring to his infant son as his “fat little Dutchman.” After several years of moving from town to town—made necessary in part because of Jack Reagan's alcoholism, which made it difficult for him to hold a job—the family settled in Dixon, Illinois, in 1920. Despite their near poverty and his father's drinking problem, Reagan later recalled his childhood in Dixon as the happiest period of his life. At Eureka College in Eureka, Illinois, Reagan played gridiron football and was active in the drama society but earned only passing grades. A popular student, he was elected class president in his senior year. Graduating in 1932 with a bachelor's degree in economics and sociology, he decided to enter radio broadcasting. He landed a job as a sportscaster at station WOC in Davenport, Iowa, by delivering entirely from memory an exciting play-by-play description of a Eureka College football game. Later he moved to station WHO in Des Moines, where, as sportscaster “Dutch Reagan,” he became popular throughout the state for his broadcasts of Chicago Cubs baseball games. Because the station could not afford to send him to Wrigley Field in Chicago, Reagan was forced to improvise a running account of the games based on sketchy details delivered over a teletype machine. In 1937 Reagan followed the Cubs to their spring training camp in southern California, a trip he undertook partly in order to try his hand at movie acting. After a successful screen test at Warner Brothers, he was soon typecast in a series of mostly B movies as a sincere, wholesome, easygoing “good guy.” (As many observers have noted, the characters that Reagan portrayed in the movies were remarkably like Reagan himself.) During the next 27 years, he appeared in more than 50 films, notably including Knute Rockne—All American (1940), Kings Row (1942), and The Hasty Heart (1950). In 1938, while filming Brother Rat, Reagan became engaged to his costar Jane Wyman, and the couple married in Hollywood two years later. They had a daughter, Maureen, in 1941 and adopted a son, Michael, a few days after his birth in 1945. Their marriage ended in divorce in 1948. Reagan was the only president to have been divorced.

In 1937 Reagan followed the Cubs to their spring training camp in southern California, a trip he undertook partly in order to try his hand at movie acting. After a successful screen test at Warner Brothers, he was soon typecast in a series of mostly B movies as a sincere, wholesome, easygoing “good guy.” (As many observers have noted, the characters that Reagan portrayed in the movies were remarkably like Reagan himself.) During the next 27 years, he appeared in more than 50 films, notably including Knute Rockne—All American (1940), Kings Row (1942), and The Hasty Heart (1950). In 1938, while filming Brother Rat, Reagan became engaged to his costar Jane Wyman, and the couple married in Hollywood two years later. They had a daughter, Maureen, in 1941 and adopted a son, Michael, a few days after his birth in 1945. Their marriage ended in divorce in 1948. Reagan was the only president to have been divorced.Commissioned a cavalry officer at the outbreak of World War II, Reagan was assigned to an army film unit based in Los Angeles, where he spent the rest of the war making training films. Although he never left the country and never saw combat, he and Wyman cooperated with the efforts of Warner Brothers to portray him as a real soldier to the public, and in newsreels and magazine photos he acted out scenes of “going off to war” and “coming home on leave.” After leaving Hollywood, Reagan became known for occasionally telling stories about his past—including stories about his happiness at “coming back from the war”—that were actually based on fictional episodes in movies. Some of Reagan's detractors pointed to such lapses to suggest that he lacked a basic interest in the truth and that he had trouble distinguishing between reality and fantasy.

Reagan had absorbed the liberal Democratic opinions of his father and became a great admirer of Franklin Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Franklin D.) after his election in 1932. Reagan's father eventually found work as an administrator in a New Deal office established in the Dixon area, a fact that Reagan continued to appreciate even after his political opinion of Roosevelt had dramatically changed.

From 1947 to 1952 Reagan served as president of the union of movie actors, the Screen Actors Guild. He fought against communist infiltration in the guild, crossing picket lines to break the sometimes violent strikes. (Such violence and chaos were abhorrent to Reagan, and, when police and students clashed in Berkeley in May 1969, Reagan, as governor of California, called out the National Guard to restore order.) Much to the disgust of union members, he testified as a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee and cooperated in the blacklisting of actors, directors, and writers suspected of leftist sympathies. Although Reagan was still a Democrat at the time (he campaigned for Harry Truman (Truman, Harry S.) in the presidential election of 1948), his political opinions were gradually growing more conservative. After initially supporting Democratic senatorial candidate Helen Douglas in 1950, he switched his allegiance to Republican Richard Nixon (Nixon, Richard M.) midway through the campaign. He supported Republican Dwight Eisenhower (Eisenhower, Dwight D.) in the presidential elections of 1952 and 1956, and in 1960 he delivered 200 speeches in support of Nixon's campaign for president against Democrat John F. Kennedy (Kennedy, John F.). He officially changed his party affiliation to Republican in 1962.

Reagan met Nancy Davis (Reagan, Nancy) (Nancy Reagan (Reagan, Nancy)), a relatively unknown actress, at a dinner party in 1949, and the two were married in a simple ceremony in 1952, at which actor William Holden (Holden, William) was best man. The Reagans appeared together in the war movie Hell Cats of the Navy in 1957. Nancy Reagan's conservative political views encouraged her husband's drift to the right.

Reagan met Nancy Davis (Reagan, Nancy) (Nancy Reagan (Reagan, Nancy)), a relatively unknown actress, at a dinner party in 1949, and the two were married in a simple ceremony in 1952, at which actor William Holden (Holden, William) was best man. The Reagans appeared together in the war movie Hell Cats of the Navy in 1957. Nancy Reagan's conservative political views encouraged her husband's drift to the right. After his acting career began to decline in the 1950s, Reagan became the host of a television drama series, General Electric Theater, as well as spokesman for the General Electric Company (General Electric Co.). In the latter capacity he toured GE plants around the country, delivering inspirational speeches with a generally conservative, pro-business message. Eventually, however, his speeches became too controversial for the company's taste, and he was fired as both spokesman and television host in 1962.

After his acting career began to decline in the 1950s, Reagan became the host of a television drama series, General Electric Theater, as well as spokesman for the General Electric Company (General Electric Co.). In the latter capacity he toured GE plants around the country, delivering inspirational speeches with a generally conservative, pro-business message. Eventually, however, his speeches became too controversial for the company's taste, and he was fired as both spokesman and television host in 1962.Governorship of California

Reagan campaigned actively for Nixon in his run for governor of California in 1962 and supported the presidential candidacy of conservative Republican Barry Goldwater (Goldwater, Barry) in 1964, serving as cochairman of California Republicans for Goldwater. In the last week of the campaign, he delivered a 30-minute nationally televised address, “A Time for Choosing,” that The Washington Post described as “the most successful political debut since William Jennings Bryan (Bryan, William Jennings) electrified the 1896 Democratic convention with his ‘Cross of Gold' speech.” Reagan's speech, which resulted in $1 million in campaign contributions for Republican candidates (the most attributable to any political speech in history), catapulted him onto the national political stage and made him an instant hero of the Republican right.

Reagan announced his candidacy for governor of California in 1966. The incumbent, Democrat Edmund G. (“Pat”) Brown (who had defeated Nixon's challenge in 1962), ridiculed Reagan's lack of experience, declaring that while he (Brown) had been serving the public, Reagan was making Bedtime for Bonzo, a 1951 movie in which Reagan starred with a chimpanzee. But Reagan turned this apparent liability into an asset by portraying himself as an ordinary citizen who was fed up with a state government that had become inefficient and unaccountable. The public also reacted well to Reagan's personality, in particular to his apparent genuineness, affability, and self-deprecating sense of humour. (When asked by a reporter how he would perform in office, Reagan replied, “I don't know. I've never played a governor.”) Reagan won the election by nearly one million votes. During his two terms as governor (1966–74), Reagan erased a substantial budget deficit inherited from the Brown administration (through the largest tax increase in the history of any state to that time) and instituted reforms in the state's welfare programs. As some observers have noted, Reagan's administrative style as governor was essentially the same as the one he would later adopt as president: he left most of the day-to-day business of government to assistants and department heads, preferring to focus on larger issues of policy and vision. Reagan followed a rigid schedule, which his aides would prepare and type up for him daily.

Reagan announced his candidacy for governor of California in 1966. The incumbent, Democrat Edmund G. (“Pat”) Brown (who had defeated Nixon's challenge in 1962), ridiculed Reagan's lack of experience, declaring that while he (Brown) had been serving the public, Reagan was making Bedtime for Bonzo, a 1951 movie in which Reagan starred with a chimpanzee. But Reagan turned this apparent liability into an asset by portraying himself as an ordinary citizen who was fed up with a state government that had become inefficient and unaccountable. The public also reacted well to Reagan's personality, in particular to his apparent genuineness, affability, and self-deprecating sense of humour. (When asked by a reporter how he would perform in office, Reagan replied, “I don't know. I've never played a governor.”) Reagan won the election by nearly one million votes. During his two terms as governor (1966–74), Reagan erased a substantial budget deficit inherited from the Brown administration (through the largest tax increase in the history of any state to that time) and instituted reforms in the state's welfare programs. As some observers have noted, Reagan's administrative style as governor was essentially the same as the one he would later adopt as president: he left most of the day-to-day business of government to assistants and department heads, preferring to focus on larger issues of policy and vision. Reagan followed a rigid schedule, which his aides would prepare and type up for him daily.Reagan made a halfhearted bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1968 as a favourite-son candidate, finishing third behind Nixon and former New York governor Nelson Rockefeller (Rockefeller, Nelson Aldrich). During his remaining years as governor, he made plans for a more serious run for the presidency, expecting that his chance would come in 1976, at the anticipated end of Nixon's second term. But Nixon's resignation in 1974 put Vice President Gerald Ford (Ford, Gerald R.) in the Oval Office. Unwilling to wait another eight years, Reagan challenged Ford with a blistering critique of his policies and appointments but lost the nomination by 60 votes.

Election of 1980

Reagan dominated the Republican primary elections in 1980. Although his strongest opponent, George Bush (Bush, George), won an upset victory in the Iowa caucuses, Reagan bounced back after a notable performance in a debate with other Republican candidates in Nashua, New Hampshire. The debate, initially sponsored by a newspaper, was first extended to only Reagan and Bush, but Reagan decided to pay for the debate and invite the rest of the candidates. When all the candidates took the stage that evening, the Bush team appeared surprised, and, as Reagan began to explain the situation, the moderator from the newspaper instructed that Reagan's microphone be turned off. Reagan responded memorably with an angry line he remembered from a Spencer Tracy movie: “I am paying for this microphone!” Reagan went on to win New Hampshire and most of the other major primaries and entered the convention with a commanding lead; he won the nomination on the first ballot with 1,939 votes to 37 for John Anderson and 13 for Bush, who had withdrawn from the contest before the vote. After some tense and ultimately fruitless negotiations with representatives of Ford, Reagan chose Bush as his running mate, and the two men campaigned against Democratic incumbents Jimmy Carter (Carter, Jimmy) and Walter Mondale (Mondale, Walter) on a platform promising steep tax cuts, increased defense spending, a balanced budget, and a constitutional amendment to ban abortion.

Reagan dominated the Republican primary elections in 1980. Although his strongest opponent, George Bush (Bush, George), won an upset victory in the Iowa caucuses, Reagan bounced back after a notable performance in a debate with other Republican candidates in Nashua, New Hampshire. The debate, initially sponsored by a newspaper, was first extended to only Reagan and Bush, but Reagan decided to pay for the debate and invite the rest of the candidates. When all the candidates took the stage that evening, the Bush team appeared surprised, and, as Reagan began to explain the situation, the moderator from the newspaper instructed that Reagan's microphone be turned off. Reagan responded memorably with an angry line he remembered from a Spencer Tracy movie: “I am paying for this microphone!” Reagan went on to win New Hampshire and most of the other major primaries and entered the convention with a commanding lead; he won the nomination on the first ballot with 1,939 votes to 37 for John Anderson and 13 for Bush, who had withdrawn from the contest before the vote. After some tense and ultimately fruitless negotiations with representatives of Ford, Reagan chose Bush as his running mate, and the two men campaigned against Democratic incumbents Jimmy Carter (Carter, Jimmy) and Walter Mondale (Mondale, Walter) on a platform promising steep tax cuts, increased defense spending, a balanced budget, and a constitutional amendment to ban abortion. Carter began the campaign in a vulnerable position. Inflation had increased from 6 percent to more than 12 percent since his first year in office, and unemployment and interest rates were also high. An even more important factor than the economy, however, was Carter's apparent inability to resolve the Iran hostage crisis, which had continued for almost a year at the time of the election. On November 4, 1979, a mob of Iranian students had stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehrān and taken the diplomatic staff there hostage. In April 1980, after months of fruitless negotiations with students and officials of Iran's revolutionary government (which had sanctioned the takeover), Carter ordered a military rescue operation, which failed dramatically. The hostage crisis contributed to a general public perception of the Carter administration as weak and indecisive, and the failed rescue mission reinforced Reagan's charge that the Democrats had allowed the country's military to deteriorate badly. In their only debate of the campaign, Reagan memorably reminded his national television audience of the country's economic problems by asking, “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” Carter, for his part, tried to make the most of Reagan's image among some of the electorate as an extremist and a warmonger, charging that as president Reagan would eliminate cherished social programs and threaten world peace. Reagan's smiling response to such charges—“There you go again” (a line he had practiced in preparation for the debate)—did not directly address the point, but it did convey a disarming image of sincerity, self-confidence, and friendliness, which most voters found appealing. On election day Reagan defeated Carter and John Anderson (who ran as an independent) with slightly more than half the popular vote, against Carter's 41 percent and Anderson's 7 percent. The vote in the electoral college was 489 to Carter's 49.

Carter began the campaign in a vulnerable position. Inflation had increased from 6 percent to more than 12 percent since his first year in office, and unemployment and interest rates were also high. An even more important factor than the economy, however, was Carter's apparent inability to resolve the Iran hostage crisis, which had continued for almost a year at the time of the election. On November 4, 1979, a mob of Iranian students had stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehrān and taken the diplomatic staff there hostage. In April 1980, after months of fruitless negotiations with students and officials of Iran's revolutionary government (which had sanctioned the takeover), Carter ordered a military rescue operation, which failed dramatically. The hostage crisis contributed to a general public perception of the Carter administration as weak and indecisive, and the failed rescue mission reinforced Reagan's charge that the Democrats had allowed the country's military to deteriorate badly. In their only debate of the campaign, Reagan memorably reminded his national television audience of the country's economic problems by asking, “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” Carter, for his part, tried to make the most of Reagan's image among some of the electorate as an extremist and a warmonger, charging that as president Reagan would eliminate cherished social programs and threaten world peace. Reagan's smiling response to such charges—“There you go again” (a line he had practiced in preparation for the debate)—did not directly address the point, but it did convey a disarming image of sincerity, self-confidence, and friendliness, which most voters found appealing. On election day Reagan defeated Carter and John Anderson (who ran as an independent) with slightly more than half the popular vote, against Carter's 41 percent and Anderson's 7 percent. The vote in the electoral college was 489 to Carter's 49.Presidency

First days

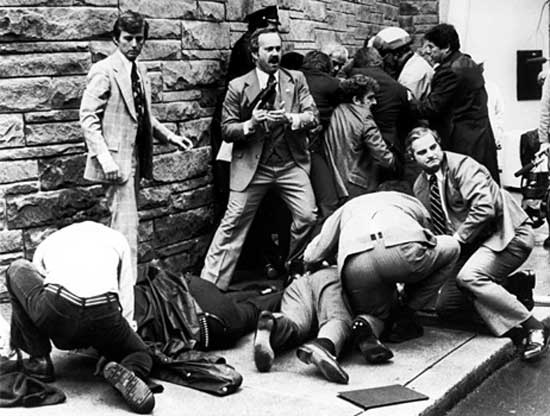

Reagan's presidency began on a dramatic note when, after the inaugural ceremony (see original text (Ronald Reagan: First Inaugural Address)), he announced at a luncheon that Iran had agreed to release the remaining American hostages. The timing of Iran's decision led to suspicions, which were never substantiated, that the Reagan campaign had made a secret deal with the Iranians to prevent the Carter administration from unveiling a so-called “October surprise”—the release of the hostages in October 1980, before election day. Then, on March 30, 1981, a deranged drifter named John W. Hinckley, Jr., fired six shots from a .22-calibre revolver at Reagan as he left a Washington, D.C., hotel. One of the bullets entered Reagan's chest, puncturing a lung and lodging one inch from his heart; another critically wounded Press Secretary James Brady. Rushed to George Washington University Hospital for emergency surgery, Reagan joked with doctors as he was being wheeled into the operating room: “I hope you're all Republicans.” After his release 12 days later, Reagan made a series of carefully staged public appearances designed to give the impression that he was recovering quickly, though in fact he remained seriously weakened for months and his workload was sharply curtailed.

Reagan's presidency began on a dramatic note when, after the inaugural ceremony (see original text (Ronald Reagan: First Inaugural Address)), he announced at a luncheon that Iran had agreed to release the remaining American hostages. The timing of Iran's decision led to suspicions, which were never substantiated, that the Reagan campaign had made a secret deal with the Iranians to prevent the Carter administration from unveiling a so-called “October surprise”—the release of the hostages in October 1980, before election day. Then, on March 30, 1981, a deranged drifter named John W. Hinckley, Jr., fired six shots from a .22-calibre revolver at Reagan as he left a Washington, D.C., hotel. One of the bullets entered Reagan's chest, puncturing a lung and lodging one inch from his heart; another critically wounded Press Secretary James Brady. Rushed to George Washington University Hospital for emergency surgery, Reagan joked with doctors as he was being wheeled into the operating room: “I hope you're all Republicans.” After his release 12 days later, Reagan made a series of carefully staged public appearances designed to give the impression that he was recovering quickly, though in fact he remained seriously weakened for months and his workload was sharply curtailed.In August 1981, 13,000 members of the national union of air traffic controllers, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO)—one of the few unions to endorse Reagan in the 1980 election—walked off their jobs, demanding higher pay and better working conditions. As federal employees, the PATCO members were forbidden by law to strike, and Reagan, on the advice of Transportation Secretary Drew Lewis, refused to negotiate and gave them 48 hours to return to work. Most of the striking controllers ignored the ultimatum and were promptly fired. Although the firings caused delays and reductions in air traffic until replacements were hired and trained, the public generally reacted positively to Reagan's action, seeing it as a sign of decisiveness and conviction. As he later wrote, it “convinced people who might have thought otherwise that I meant what I said.”

Domestic policies

Following the so-called “supply-side” economic program he propounded in his campaign, Reagan proposed massive tax cuts—30 percent reductions in both individual and corporate income taxes over a three-year period—which he believed would stimulate the economy and eventually increase revenues from taxes as income levels grew. At the same time, he proposed large increases in military expenditures ($1.5 trillion over a five-year period) and significant cuts in “discretionary” spending on social-welfare programs such as education, food stamps, low-income housing, school lunches for poor children, Medicaid (the major program of health insurance for the poor), and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). In 1981 Congress passed most of the president's budget proposals, though the tax cut was scaled back slightly, to 25 percent.

Following the so-called “supply-side” economic program he propounded in his campaign, Reagan proposed massive tax cuts—30 percent reductions in both individual and corporate income taxes over a three-year period—which he believed would stimulate the economy and eventually increase revenues from taxes as income levels grew. At the same time, he proposed large increases in military expenditures ($1.5 trillion over a five-year period) and significant cuts in “discretionary” spending on social-welfare programs such as education, food stamps, low-income housing, school lunches for poor children, Medicaid (the major program of health insurance for the poor), and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). In 1981 Congress passed most of the president's budget proposals, though the tax cut was scaled back slightly, to 25 percent. The results were mixed. A severe recession in 1982 pushed the nation's unemployment rate to nearly 11 percent, the highest it had been since the Great Depression. Bankruptcies and farm foreclosures reached record levels. The country's trade deficit increased from $25 billion in 1980 to $111 billion in 1984. In addition, the huge increases in military spending, combined with insufficient cuts in other programs, produced massive budget deficits, the largest in the country's history; by the end of Reagan's second term, the deficits would contribute to a tripling of the national debt, to more than $2.5 trillion. In order to address the deficit problem, Reagan backed away from strict supply-side theories to support a $98.3 billion tax increase in 1982. By early 1983 the economy had begun to recover, and by the end of that year unemployment and inflation were significantly reduced; they remained relatively low in later years. Economic growth continued through the remainder of Reagan's presidency, a period that his supporters would hail as “the longest peacetime expansion in American history.” Critics charged that the tax cuts and the fruits of economic growth benefited mainly the wealthy and that the gap between rich and poor had grown wider.

The results were mixed. A severe recession in 1982 pushed the nation's unemployment rate to nearly 11 percent, the highest it had been since the Great Depression. Bankruptcies and farm foreclosures reached record levels. The country's trade deficit increased from $25 billion in 1980 to $111 billion in 1984. In addition, the huge increases in military spending, combined with insufficient cuts in other programs, produced massive budget deficits, the largest in the country's history; by the end of Reagan's second term, the deficits would contribute to a tripling of the national debt, to more than $2.5 trillion. In order to address the deficit problem, Reagan backed away from strict supply-side theories to support a $98.3 billion tax increase in 1982. By early 1983 the economy had begun to recover, and by the end of that year unemployment and inflation were significantly reduced; they remained relatively low in later years. Economic growth continued through the remainder of Reagan's presidency, a period that his supporters would hail as “the longest peacetime expansion in American history.” Critics charged that the tax cuts and the fruits of economic growth benefited mainly the wealthy and that the gap between rich and poor had grown wider.In keeping with his aim of reducing the role of government in the country's economic life, Reagan cut the budgets of many government departments and relaxed or ignored the enforcement of laws and regulations administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of the Interior, the Department of Transportation, and the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, among other agencies. After the administration and Congress reduced regulations governing the savings and loan industry in the early 1980s, many savings institutions expanded recklessly through the decade and eventually collapsed, requiring bailouts by the federal government that cost taxpayers some $500 billion.

During his tenure in office, Reagan appointed more than half the federal judiciary and three new justices of the Supreme Court: (Supreme Court of the United States) Sandra Day O'Connor (O'Connor, Sandra Day), the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court, Anthony Kennedy (Kennedy, Anthony), and Antonin Scalia (Scalia, Antonin). He also elevated William Rehnquist (Rehnquist, William) to chief justice in 1986 upon the retirement of Warren Burger (Burger, Warren E.).

Foreign affairs

When he entered office in 1980, Reagan believed that the United States had grown weak militarily and had lost the respect it once commanded in world affairs. Aiming to restore the country to a position of moral as well as military preeminence in the world, he called for massive increases in the defense budget to expand and modernize the military and urged a more aggressive approach to combating communism and related forms of leftist totalitarianism.

Relations with the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

Reagan's militant anticommunism, combined with his penchant for harsh anti-Soviet rhetoric, was one of many factors that contributed to a worsening of relations with the Soviet Union in the first years of his presidency. At his first press conference as president, Reagan audaciously questioned the legitimacy of the Soviet government; two years later, in a memorable speech in Florida, he denounced the Soviet Union as “an evil empire” and “the focus of evil in the modern world.” (The Soviets responded by saying that Reagan's remarks showed that his administration “can think only in terms of confrontation and bellicose, lunatic anticommunism.”) The behaviour of the Soviet Union itself also strained relations—especially in December 1981, when the communist government of Poland, under intense pressure from Moscow, imposed martial law on the country to suppress the independent labour movement Solidarity; and in September 1983, when the Soviets shot down a Korean airliner en route from Alaska to Seoul as it strayed over strategically sensitive territory on Sakhalin Island. All 269 people aboard were killed, including 61 Americans. Reagan's massive military spending program, the largest in American peacetime history, was undoubtedly another factor, though some observers argued that the buildup—through the strain it imposed on the Soviet economy—was actually responsible for a host of positive developments in Reagan's second term, including a more accommodating Soviet position in arms negotiations, a weakening of the influence of hard-liners in the Soviet leadership, making possible the glasnost (“openness”) and perestroika (“restructuring”) policies of moderate Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (Gorbachev, Mikhail) after 1985, and even the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself in 1990–91.

A significant component of Reagan's military buildup was his 1983 proposal for a space-based missile defense system that would use lasers and other as-yet-undeveloped killing technologies to destroy incoming Soviet nuclear missiles well before they could reach their targets in the United States. The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), dubbed “Star Wars” after the popular science-fiction movie of the late 1970s, was denounced by the Soviets, including Gorbachev, as a dangerous escalation of the arms race, a position also taken by many critics at home. Meanwhile, others argued that the project was technologically impossible and potentially a “black hole” in the country's defense budget. In later years, however, former Soviet officials cited SDI as a factor in the eventual collapse of their country, for it showed that the Soviet Union was politically unprepared for and economically incapable of competing in a new arms race with the United States, especially one led by someone as unrelenting as Reagan. Although Reagan never abandoned his support for SDI, it was eventually reconceived as a much smaller and more conventional defensive system than the one he originally proposed.

U.S.-Soviet relations improved considerably during Reagan's second term, not least because Reagan softened his anticommunist rhetoric and adopted a more encouraging tone toward the changes then taking place in the Soviet Union. At a dramatic summit meeting in Reykjavík, Iceland, in October 1986, Gorbachev proposed a 50 percent reduction in the nuclear arsenals of each side, and for a time it seemed as though a historic agreement would be reached. Although the summit ended in failure owing to differences over SDI, it was followed up in December 1987 by a treaty eliminating intermediate-range nuclear forces (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty) (INF) on European soil. The INF Treaty (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty) was the first arms-control pact to require an actual reduction in nuclear arsenals rather than merely restricting their proliferation.

U.S.-Soviet relations improved considerably during Reagan's second term, not least because Reagan softened his anticommunist rhetoric and adopted a more encouraging tone toward the changes then taking place in the Soviet Union. At a dramatic summit meeting in Reykjavík, Iceland, in October 1986, Gorbachev proposed a 50 percent reduction in the nuclear arsenals of each side, and for a time it seemed as though a historic agreement would be reached. Although the summit ended in failure owing to differences over SDI, it was followed up in December 1987 by a treaty eliminating intermediate-range nuclear forces (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty) (INF) on European soil. The INF Treaty (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty) was the first arms-control pact to require an actual reduction in nuclear arsenals rather than merely restricting their proliferation.The Middle East and Central America

Following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982, Reagan dispatched 800 Marines to join an international force to oversee the evacuation of Palestinian guerrillas from West Beirut, then surrounded by Israeli troops. After Israel withdrew its troops from the Beirut area in September 1983, the Marine contingent remained—along with forces from Italy, France, and Britain—to protect the fragile Lebanese government, thereby identifying itself with one of the factions in the country's long and bloody civil war, which had begun in 1975. On the morning of October 23, 1983, a suicide bomber drove a truck laden with explosives into the Marine compound at the Beirut airport, killing 241 Marines and wounding 100 others. Although later investigations blamed the Marine chain of command for poor security at the base and “serious errors in judgment,” Reagan decided to accept full blame for the tragedy himself, saying that the Marine commanders had “suffered enough.” Reagan withdrew the Marines from Lebanon in February 1984.

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean island nation of Grenada, Prime Minister Maurice Bishop was deposed and executed in a bloody coup by radical elements of his leftist New Jewel Movement. Less than a week later, and only one day after the bombing of the Marine compound in Lebanon, Reagan ordered an invasion, which he justified as necessary to prevent the country from becoming a dangerous Soviet outpost and to protect American students at the medical school there. Joined by a contingent of troops from neighbouring Caribbean countries, U.S. forces quickly subdued elements of the Grenadan army and a small number of Cuban soldiers and construction workers. Critics immediately charged that the administration had staged the invasion to divert public attention from the bombing in Lebanon.

In January 1986 Reagan announced the imposition of economic sanctions on Libya and froze the country's assets in the United States, charging the Libyan government of General Muammar al-Qaddafi (Qaddafi, Muammar al-) with sponsoring acts of international terrorism, including the December 1985 attacks on offices of the Israeli airline El Al in Rome and Vienna. In March a U.S. Navy task force conducted “freedom of navigation” exercises in the Gulf of Sidra, beyond the self-proclaimed territorial boundary Libya called the “Line of Death.” Libya fired antiaircraft missiles at American warplanes, and the United States responded with attacks on Libyan ships and missile installations. Then, on April 5, two people, including an American serviceman, were killed by a bomb explosion in a discotheque in West Berlin. Blaming Libya, the United States carried out retaliatory bombing raids on “terrorist-related targets” in Libya on April 14–15, including an attack on Qaddafi's residential compound in Tripoli.

In keeping with Reagan's belief that the United States should do more to prevent the spread of communism, his administration expanded military and economic assistance to friendly Third World governments battling leftist insurgencies, and he actively supported guerrilla movements and other opposition forces in countries with leftist governments. This policy, which became known as the Reagan Doctrine, was applied with particular zeal in Latin America. During the 1980s the United States supported military-dominated governments in El Salvador in a bloody civil war with the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional; FMLN), providing the country with some $4 billion in military and economic aid and helping to organize and train elite units of the Salvadoran army. In Nicaragua, following the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (Sandinista) (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional; FSLN) in 1979, the Sandinista government strengthened its ties to Cuba and other countries of the socialist bloc, a move that the Reagan administration regarded as a threat to the national security of the United States. In 1981 Reagan authorized $20 million to recruit and train a band of anti-Sandinista guerrillas, many of whom were former supporters of Somoza, to overthrow the Sandinista government. Numbering about 15,000 by the mid-1980s, the “Contras,” as they came to be called, were never a serious military threat to the Sandinistas, though they did cause millions of dollars in damage to the Nicaraguan economy through their attacks on farms and cooperatives, infrastructure, and other civilian targets. Using its influence in international lending agencies such as the World Bank, the United States was able to block most Nicaraguan loan requests from 1982, and in 1985 the administration declared a trade embargo. These measures, combined with Contra attacks and the Sandinista's own mismanagement, effectively undermined the Nicaraguan economy by the end of the 1980s.

The Iran-Contra Affair

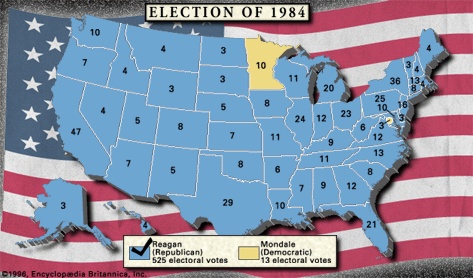

At the time of the presidential election of 1984, Reagan was at the height of his popularity. Using slogans such as “It's morning in America” and “America is back,” his reelection campaign emphasized the country's economic prosperity and its renewed leadership role in world affairs. On election day Reagan and Bush easily defeated their Democratic opponents, Walter Mondale (Mondale, Walter) and Geraldine Ferraro (Ferraro, Geraldine A.), by 59 percent to 41 percent of the popular vote; in the electoral college Reagan received 525 votes to Mondale's 13, the largest number of electoral votes of any candidate in history. With most of the country behind him, Reagan's prospects in his second term appeared bright. (See primary source document: Second Inaugural Address (Ronald Reagan: Second Inaugural Address).) Only two years later, however, he would become embroiled in the worst scandal of his political career, one that would cost him much popular and party support and significantly impair his ability to lead the country.

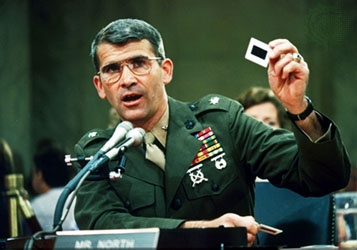

At the time of the presidential election of 1984, Reagan was at the height of his popularity. Using slogans such as “It's morning in America” and “America is back,” his reelection campaign emphasized the country's economic prosperity and its renewed leadership role in world affairs. On election day Reagan and Bush easily defeated their Democratic opponents, Walter Mondale (Mondale, Walter) and Geraldine Ferraro (Ferraro, Geraldine A.), by 59 percent to 41 percent of the popular vote; in the electoral college Reagan received 525 votes to Mondale's 13, the largest number of electoral votes of any candidate in history. With most of the country behind him, Reagan's prospects in his second term appeared bright. (See primary source document: Second Inaugural Address (Ronald Reagan: Second Inaugural Address).) Only two years later, however, he would become embroiled in the worst scandal of his political career, one that would cost him much popular and party support and significantly impair his ability to lead the country.In early November 1985, at the suggestion of the head of the National Security Council (NSC), William (“Bud”) McFarlane, Reagan authorized a secret initiative to sell antitank and antiaircraft missiles to Iran in exchange for that country's help in securing the release of Americans held hostage by terrorist (terrorism) groups in Lebanon. The initiative directly contradicted the administration's publicly stated policy of refusing to negotiate with terrorists or to aid countries—such as Iran—that supported international terrorism. News of the arms-for-hostages deal, first made public in November 1986 (only one month after Reagan ordered raids on Libya in retaliation for its alleged involvement in the Berlin bombing), proved intensely embarrassing to the president. Even more damaging, however, was the announcement later that month by Attorney General Edwin Meese that a portion of the $48 million earned from the sales had been diverted to a secret fund to purchase weapons and supplies for the Contras in Nicaragua. The diversion was undertaken by an obscure NSC aide, U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, with the approval of McFarlane's successor at the NSC, Rear Admiral John Poindexter. (North, as it was later revealed, had also engaged in private fund-raising for the Contras.) These activities constituted a violation of a law passed by Congress in 1984 (the second Boland Amendment) that forbade direct or indirect American military aid to the Contra insurgency.

In response to the crisis, by this time known as the Iran-Contra Affair, Reagan fired both North and Poindexter and appointed a special commission, headed by former senator John Tower of Texas (the Tower Commission), to investigate the matter. An independent counsel, Judge Lawrence Walsh, was also appointed, and the House and Senate began joint hearings to examine both the arms sales and the military assistance to the Contras. As a result of Walsh's investigations, North and Poindexter were convicted on charges of obstructing justice and related offenses, but their convictions were overturned on appeal, on the ground that testimony given at their trials had been influenced by information they had supplied to Congress under a limited grant of immunity. Reagan accepted responsibility for the arms-for-hostages deal but denied any knowledge of the diversion. Although no evidence came to light to indicate that he was more deeply involved, many in Congress and the public remained skeptical. Nevertheless, most of the public eventually appeared willing to forgive him for whatever they thought he had done, and his popularity, which had dropped dramatically during the first months of the crisis, gradually recovered.

In response to the crisis, by this time known as the Iran-Contra Affair, Reagan fired both North and Poindexter and appointed a special commission, headed by former senator John Tower of Texas (the Tower Commission), to investigate the matter. An independent counsel, Judge Lawrence Walsh, was also appointed, and the House and Senate began joint hearings to examine both the arms sales and the military assistance to the Contras. As a result of Walsh's investigations, North and Poindexter were convicted on charges of obstructing justice and related offenses, but their convictions were overturned on appeal, on the ground that testimony given at their trials had been influenced by information they had supplied to Congress under a limited grant of immunity. Reagan accepted responsibility for the arms-for-hostages deal but denied any knowledge of the diversion. Although no evidence came to light to indicate that he was more deeply involved, many in Congress and the public remained skeptical. Nevertheless, most of the public eventually appeared willing to forgive him for whatever they thought he had done, and his popularity, which had dropped dramatically during the first months of the crisis, gradually recovered.Retirement and declining health

In the presidential election of 1988, Reagan campaigned actively for the Republican nominee, Vice President Bush. In large part because of Reagan's continued popularity, Bush defeated Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis (Dukakis, Michael S.) by 53 percent to 46 percent in the popular vote; the vote in the electoral college was 426 to 111. Reagan retired to his home in Los Angeles, where he wrote his autobiography, An American Life (1990). In 1994, in a letter to the American people, Reagan disclosed that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer disease, a degenerative brain disorder.

In the presidential election of 1988, Reagan campaigned actively for the Republican nominee, Vice President Bush. In large part because of Reagan's continued popularity, Bush defeated Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis (Dukakis, Michael S.) by 53 percent to 46 percent in the popular vote; the vote in the electoral college was 426 to 111. Reagan retired to his home in Los Angeles, where he wrote his autobiography, An American Life (1990). In 1994, in a letter to the American people, Reagan disclosed that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer disease, a degenerative brain disorder. To some observers Reagan's declining health had been evident for many years. Mindful of her husband's diminished capacity, Nancy Reagan occasionally would screen him from the press by intercepting reporters' questions and then whispering an appropriate response in his ear. Reagan's health problems made public appearances difficult for the former president, but his popularity hardly waned. National Airport in Washington, D.C., was renamed Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport by Congress and President Bill Clinton in February 1998. Reagan's conservative policies and heated rhetoric had always infuriated liberals, and his administration had experienced its share of scandals and disappointments. But to his millions of fans and political admirers, this tribute was the least the government could do for the man who had helped to end the Cold War and restored, however fleetingly, the country's confidence in itself and its faith in a better tomorrow.

To some observers Reagan's declining health had been evident for many years. Mindful of her husband's diminished capacity, Nancy Reagan occasionally would screen him from the press by intercepting reporters' questions and then whispering an appropriate response in his ear. Reagan's health problems made public appearances difficult for the former president, but his popularity hardly waned. National Airport in Washington, D.C., was renamed Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport by Congress and President Bill Clinton in February 1998. Reagan's conservative policies and heated rhetoric had always infuriated liberals, and his administration had experienced its share of scandals and disappointments. But to his millions of fans and political admirers, this tribute was the least the government could do for the man who had helped to end the Cold War and restored, however fleetingly, the country's confidence in itself and its faith in a better tomorrow.Cabinet of President Ronald Reagan

Cabinet of President Ronald Reagan Cabinet of President Ronald ReaganThe table provides a list of cabinet members in the administration of President Ronald Reagan.

Additional Reading

Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Ronald Reagan, 8 vol. in 15 (1982–90), collects his speeches and statements. Reagan's own works include Speaking My Mind: Selected Speeches (1989), mostly from his presidential years, and his autobiography, An American Life (1990).A biography covering Reagan's life until the gubernatorial campaign of 1966 is Anne Edwards, Early Reagan (1987); while Lou Cannon, Reagan (1982), takes up from 1966 through the early 1980s. Reagan's Hollywood career, spanning 1937 to 1952, is the focus of Stephen Vaughn, Ronald Reagan in Hollywood: Movies and Politics (1994).General analyses of Reagan and his administration include Ronnie Dugger, On Reagan: The Man & His Presidency (1983), contrasting Reagan's prepresidential positions with his presidential policies; Fred I. Greenstein (ed.), The Reagan Presidency: An Early Assessment (1983); Robert Dallek, Ronald Reagan: The Politics of Symbolism (1984); John L. Palmer (ed.), Perspectives on the Reagan Years (1986), a collection of essays on the man and his presidency; Garry Wills, Reagan's America: Innocents at Home (1987), an interpretation of his appeal; Jane Mayer and Doyle McManus, Landslide: The Unmaking of the President, 1984–1988 (1988), describing Reagan's second term and the Iran-Contra events; Bob Schieffer and Gary Paul Gates, The Acting President (1989), postulating that Reagan's advisers ran the country; Lou Cannon, President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime (1991); and Michael Schaller, Reckoning with Reagan: America and Its President in the 1980s (1992). Evaluations of the impact of Reagan's presidency on U.S. politics are Charles O. Jones (ed.), The Reagan Legacy: Promise and Performance (1988); and Sidney Blumenthal and Thomas Byrne Edsall (eds.), The Reagan Legacy (1988), which also treats economics, diplomacy, law, culture, and ideology.Works on the domestic and foreign policies of the Reagan era include John L. Palmer and Isabel V. Sawhill (eds.), The Reagan Experiment: An Examination of Economic and Social Policies Under the Reagan Administration (1982), and The Reagan Record: An Assessment of America's Changing Domestic Priorities (1984); Laurence I. Barrett, Gambling with History: Ronald Reagan in the White House (1983); Michael Mandelbaum and Strobe Talbott, Reagan and Gorbachev (1987); Michael J. Boskin, Reagan and the Economy: The Successes, Failures, and Unfinished Agenda (1987); Norman C. Amaker, Civil Rights and the Reagan Administration (1988); Martin Anderson, Revolution: The Reagan Legacy, expanded and updated ed. (1990); C. Brant Short, Ronald Reagan and the Public Lands: America's Conservation Debate, 1979–1984 (1989); Coral Bell, The Reagan Paradox: American Foreign Policy in the 1980s (1989); and David E. Kyvig (ed.), Reagan and the World (1990).Among the numerous books written by former members of Reagan's staff are Donald T. Regan, For the Record: From Wall Street to Washington (1988); Peggy Noonan, What I Saw at the Revolution: A Political Life in the Reagan Era (1990); and Edwin Meese III, With Reagan: The Inside Story (1992).Reagan's rhetoric is explored in Mark Green and Gail MacColl, There He Goes Again: Ronald Reagan's Reign of Error (1983), compiling all his spoken blunders; Paul D. Erickson, Reagan Speaks: The Making of an American Myth (1985); and Mary E. Stuckey, Playing the Game: The Presidential Rhetoric of Ronald Reagan (1990).The life of the first lady, Nancy Davis Reagan, is told in Laurence Leamer, Make-Believe: The Story of Nancy & Ronald Reagan (1983).