bovid

mammal

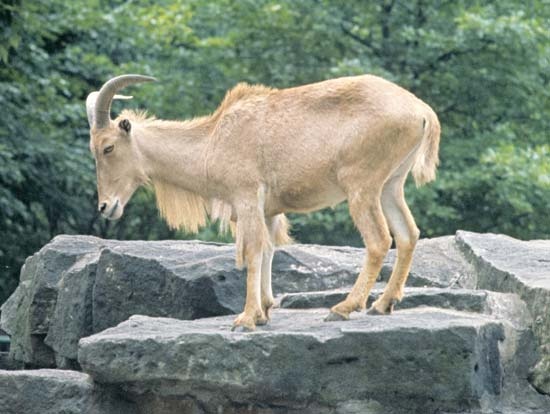

any hoofed mammal in the family Bovidae (order Artiodactyla (artiodactyl)), which includes the antelopes (antelope), sheep, goats (goat), cattle, buffalo, and bison. What sets the Bovidae apart from other cud-chewing artiodactyls (notably deer, family Cervidae) is the presence of horns (horn) consisting of a sheath covering a bony core that grows from the skull's frontal bones. Unlike the antlers of deer and the American pronghorn, bovid horns do not branch and are never shed. The males of all species and the females of about two-thirds of all species have horns—of every possible shape and size, from the short, straight spikes of duikers (duiker) and dwarf antelopes to the huge scimitar-shaped horns of wild goats and the sable antelope and to the long corkscrew horns of the blackbuck, kudu, and markhor. There are 143 different species and 50 genera of Bovidae, including one completely new species placed in its own genus, the saola, discovered only in the 1990s in the montane forests that divide Laos and Vietnam.

any hoofed mammal in the family Bovidae (order Artiodactyla (artiodactyl)), which includes the antelopes (antelope), sheep, goats (goat), cattle, buffalo, and bison. What sets the Bovidae apart from other cud-chewing artiodactyls (notably deer, family Cervidae) is the presence of horns (horn) consisting of a sheath covering a bony core that grows from the skull's frontal bones. Unlike the antlers of deer and the American pronghorn, bovid horns do not branch and are never shed. The males of all species and the females of about two-thirds of all species have horns—of every possible shape and size, from the short, straight spikes of duikers (duiker) and dwarf antelopes to the huge scimitar-shaped horns of wild goats and the sable antelope and to the long corkscrew horns of the blackbuck, kudu, and markhor. There are 143 different species and 50 genera of Bovidae, including one completely new species placed in its own genus, the saola, discovered only in the 1990s in the montane forests that divide Laos and Vietnam. Bovids are far and away the most diverse, widespread, and abundant family of hoofed mammals. Their size ranges from the 1.5-kg (3-pound) royal antelope to the 1,000-kg (2,200-pound) bison and wild oxen (ox) (see gaur). They occupy virtually every kind of habitat available to terrestrial herbivores (herbivore) in Africa, Eurasia, and North America, where they span the full range of biomes (biome) from the equatorial rainforests of Africa (royal antelope and duiker) to the Arctic tundra ( musk ox).

Bovids are far and away the most diverse, widespread, and abundant family of hoofed mammals. Their size ranges from the 1.5-kg (3-pound) royal antelope to the 1,000-kg (2,200-pound) bison and wild oxen (ox) (see gaur). They occupy virtually every kind of habitat available to terrestrial herbivores (herbivore) in Africa, Eurasia, and North America, where they span the full range of biomes (biome) from the equatorial rainforests of Africa (royal antelope and duiker) to the Arctic tundra ( musk ox). Many grazing species that inhabited vast open plains and steppes once had populations numbering in the millions. The prime example is the dominance of America's prairies and Great Plains by a single species, the bison, which numbered from 30–60 million animals. In Africa a mix of species, mainly antelopes, ranged tropical savannas and subdeserts and the temperate Highveld grasslands (Africa) of South Africa in uncounted millions, while in Asia gazelles and their allies were equally abundant on steppe and subdesert.

Many grazing species that inhabited vast open plains and steppes once had populations numbering in the millions. The prime example is the dominance of America's prairies and Great Plains by a single species, the bison, which numbered from 30–60 million animals. In Africa a mix of species, mainly antelopes, ranged tropical savannas and subdeserts and the temperate Highveld grasslands (Africa) of South Africa in uncounted millions, while in Asia gazelles and their allies were equally abundant on steppe and subdesert.The fate of the bison, which was brought to the verge of extinction by hide and meat hunters late in the 19th century, was repeated in Asia and Africa. During the 20th century, efforts to save wildlife and wilderness resulted in the establishment of a worldwide network of protected areas. However, these amount to less than 10 percent of the ecosystems that they were intended to conserve. As humankind has continued to increase, wildlife and natural habitats outside of these protected areas have continued to disappear and have been replaced by settlements, cultivation, and livestock. Now millions upon millions of cattle, sheep, and goats dominate and usually degrade the savannas, steppes, and subdeserts, leaving little room for the remaining wild bovids. Thanks to the demand for their meat, hides, and milk, livestock now inhabit every continent except Antarctica. In an ironic turn of events, out of the extraordinary array of 143 bovid species, only one sheep, one goat, and three bovine species have been domesticated (domestication). Yet, husbanded by humans, these three species have played a major role in hastening the demise of all the rest, including species exquisitely adapted to ecosystems in which livestock can survive only through human intervention.

However, large populations of a few wild bovids still survive to show what the ecosystems of Africa and Asia were like when they were still intact. Among these populations are two million wildebeest and gazelles in the Serengeti (Serengeti National Park) ecosystem and possibly hundreds of thousands of white-eared kob and tiang on the floodplains of southern Sudan. Over a million saiga lived in Kazakhstan and Kalmykia (Kalmykiya) until the early 1990s, when the breakup of the Soviet Union left them largely unprotected, and the unsettled steppe of eastern Mongolia still supports an estimated one million Mongolian gazelles.

However, large populations of a few wild bovids still survive to show what the ecosystems of Africa and Asia were like when they were still intact. Among these populations are two million wildebeest and gazelles in the Serengeti (Serengeti National Park) ecosystem and possibly hundreds of thousands of white-eared kob and tiang on the floodplains of southern Sudan. Over a million saiga lived in Kazakhstan and Kalmykia (Kalmykiya) until the early 1990s, when the breakup of the Soviet Union left them largely unprotected, and the unsettled steppe of eastern Mongolia still supports an estimated one million Mongolian gazelles.Bovids are the most recent and adaptable family of hoofed mammals to evolve. The earliest bovid, known from fossil horn cores, occurs in Eurasia in the Miocene Epoch about 18 million years ago. Eotragus was a small, solitary forest and bush dweller dependent on cover. Africa's duikers and dwarf antelopes are considered closest to this ancestral type. The subsequent radiation of bovid species followed the spread of grasses, which in turn followed a change from a subtropical to a cooler, more seasonal climate in the middle Miocene. This climate change replaced subtropical woodlands with more open and productive habitats. With their superior ability to extract nutrients from a fibrous diet, ruminants evolved into a variety of species that could use a relatively narrow range of ecological conditions more efficiently than other less-specialized animals. Among the ruminants, the bovids were singularly adept at tailoring their size, shape, feeding apparatus, digestive system, dispersion pattern, and social system to a particular habitat. By partitioning ecosystems into many segments (giving each species a narrow niche), they became the most diverse and abundant large herbivores (herbivore).

The opening of a land bridge across the Red Sea connected the Arabian Peninsula and Africa during cool periods when polar ice caps lowered the sea level and thus enabled the interchange of Asian and African bovids and other ruminants. The first ruminants to enter Africa arrived in the early Miocene, before the bovids arose. Horn cores unearthed in North Africa show that Eotragus crossed over soon after evolving in Eurasia. By the mid-Miocene Gazella (gazelle), one of the oldest bovid genera, was present in East Africa and widespread in Eurasia. By the late Miocene African bovids had diversified into nine distinct tribes, most of which had Asian relatives.

However, most of today's genera and species of bovids appeared only during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, following a major invasion of Asian genera into Africa five million years ago. During the Pleistocene Ice Age, while most of the Eurasian tropical savanna fauna became extinct, Africa remained the main refuge of Plio-Pleistocene mammals.

The alternating expansion and contraction of the equatorial rainforest during wet and dry periods of the Ice Age promoted speciation by isolating populations of the same species that then became different subspecies and species in the process of adapting to different ecological conditions. Meanwhile, bovids adapted to cold climates evolved on the northern continents; most notable among these bovids were members of the subfamily Caprinae (goats, sheep, goat antelopes (goat antelope), and musk oxen), bovines ( yak, bison, and the aurochs, the ancestor of domestic cattle), and the gazelle tribe (Antilopini; e.g., the Mongolian gazelle; see table).

The alternating expansion and contraction of the equatorial rainforest during wet and dry periods of the Ice Age promoted speciation by isolating populations of the same species that then became different subspecies and species in the process of adapting to different ecological conditions. Meanwhile, bovids adapted to cold climates evolved on the northern continents; most notable among these bovids were members of the subfamily Caprinae (goats, sheep, goat antelopes (goat antelope), and musk oxen), bovines ( yak, bison, and the aurochs, the ancestor of domestic cattle), and the gazelle tribe (Antilopini; e.g., the Mongolian gazelle; see table).At the climax of bovid diversity and abundance in the later Pliocene and Pleistocene (which has been called the golden age of mammals), there were many more genera and species than there are now. After the Ice Age ended some 10,000 years ago, many bovids and other ruminants became extinct in the Northern Hemisphere. Predation by hunter-gatherers has been blamed in some cases. This was also when humankind began to domesticate animals and cultivate crops, with eventual dire consequences both for their wild progenitors and the natural environment.

However, in the tropical refuge of sub-Saharan Africa, although some mammals went extinct (e.g., giant forms of buffalo and hartebeest), most of the genera and species that evolved during the golden age of mammals survived to the present. All but four of the 75 African bovid species are antelopes, and south of the Sahara there are only one buffalo, one sheep (the aoudad) and two goats (ibexes (ibex)). Conversely, there are only 15 antelope species in Eurasia, all but three of which are members of the gazelle tribe, and none in North America. Bovid diversity on these northern continents reposes mainly in sheep, goats, and goat antelopes.

However, in the tropical refuge of sub-Saharan Africa, although some mammals went extinct (e.g., giant forms of buffalo and hartebeest), most of the genera and species that evolved during the golden age of mammals survived to the present. All but four of the 75 African bovid species are antelopes, and south of the Sahara there are only one buffalo, one sheep (the aoudad) and two goats (ibexes (ibex)). Conversely, there are only 15 antelope species in Eurasia, all but three of which are members of the gazelle tribe, and none in North America. Bovid diversity on these northern continents reposes mainly in sheep, goats, and goat antelopes.Nevertheless, despite loss of habitat, competition with domestic species, and overhunting virtually everywhere bovids occur, few species are yet extinct. However, many species are endangered (endangered species), and the survival of all is now entirely dependent on human beings. In the table of bovid subfamilies and tribes, the numbers of species are noted for each continent. Note that the differences between tribes of antelopes are as great as the differences between, for example, cattle (Bovini) and goats (Caprini). Members of the same tribe, which share descent from a common ancestor, mostly inhabit the same biome, occupy somewhat similar habitats, and have a similar conformation, behavioral repertoire, social organization, and mating system. (The wild Bovini are a notable exception in that they exploit a wide variety of biomes and habitats.)

Despite the many different species of bovids, their social organization can be categorized as either unsocial or social, and their mating system can be categorized as either monogamous and territorial, polygynous and territorial, or based on a male dominance hierarchy. Furthermore, there is a clear dichotomy between bovids that live in closed habitats (e.g., forest and bush) and those that live in open habitats (e.g., plains and mountains). Through the process of convergence, species of different lineages that have adapted for similar habitats come to share a number of correlated traits. Thus, closed-habitat bovids (e.g., duiker, dik-dik, and reedbuck) have a body plan that is adapted for moving in dense undergrowth, rely on hiding and concealing coloration to avoid predators, browse selectively on nonfibrous vegetation, are solitary or monogamous, and are territorial. Open-habitat bovids are mostly medium to large, do not hide except in early infancy, have a build adapted for flight in the open, have a conspicuous and distinctive coloration that advertises their presence and species, are mainly grazers or mixed feeders (graze and browse), and form herds (see antelope).

Whether the mating system is territorial or based on a male dominance hierarchy may be linked to phylogeny. The members of the subfamilies Caprinae and Bovinae, which appear to have separated from the main bovid line very early, are virtually all nonterritorial. For the rest, the Antilopinae and the duiker tribe, breeding males are territorial. All African bovids bear single young, whereas twins are common among the Antilopini, Caprini, and Boselaphini of the Northern Hemisphere.

- Museum of Fine Arts

- Museum of Islamic Art

- Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires

- Museum of London

- Museum of Modern Art

- Museum of Science

- Museum of Science and Industry

- Museum of the History of Science

- Museum of the Venice Palace

- museum, operation of

- museums, history of

- museum, types of

- Museveni, Yoweri Kaguta

- Musgrave Ranges

- Musgrave, Samuel

- Musgrave, Story

- Musgrave, Thea

- Mushanokōji Saneatsu

- Musharraf, Pervez

- Mushin

- mushroom

- mushroom poisoning

- mushāhadah

- Musial, Stan

- music