solar cell

electronics

Introduction

also called photovoltaic cell

any device that directly converts the energy in light into electrical energy through the photovoltaic effect. The overwhelming majority of solar cells are fabricated from silicon—with increasing efficiency and lowering cost as the materials range from amorphous (noncrystalline) to polycrystalline to crystalline (single crystal) silicon forms. Unlike batteries (battery) or fuel cells (fuel cell), solar cells do not utilize chemical reactions (chemical reaction) or require fuel to produce electric power, and, unlike electric generators (electric generator), they do not have any moving parts.

any device that directly converts the energy in light into electrical energy through the photovoltaic effect. The overwhelming majority of solar cells are fabricated from silicon—with increasing efficiency and lowering cost as the materials range from amorphous (noncrystalline) to polycrystalline to crystalline (single crystal) silicon forms. Unlike batteries (battery) or fuel cells (fuel cell), solar cells do not utilize chemical reactions (chemical reaction) or require fuel to produce electric power, and, unlike electric generators (electric generator), they do not have any moving parts.

Solar cells can be arranged into large groupings called arrays. These arrays, composed of many thousands of individual cells, can function as central electric power stations, converting sunlight into electrical energy for distribution to industrial, commercial, and residential users. Solar cells in much smaller configurations, commonly referred to as solar cell panels or simply solar panels, have been installed by homeowners on their rooftops to replace or augment their conventional electric supply. Solar cell panels also are used to provide electric power in many remote terrestrial locations where conventional electric power sources are either unavailable or prohibitively expensive to install. Because they have no moving parts that could need maintenance or fuels that would require replenishment, solar cells provide power for most space installations, from communications and weather satellites to space stations (space station). (Solar power is insufficient for space probes sent to the outer planets of the solar system or into interstellar space (interstellar medium), however, because of the diffusion of radiant energy with distance from the Sun.) Another growing application of solar cells is in consumer products, such as electronic toys, handheld calculators, and portable radios. Solar cells used in devices of this kind may utilize artificial light (e.g., from incandescent and fluorescent lamps) as well as sunlight.

Solar cells can be arranged into large groupings called arrays. These arrays, composed of many thousands of individual cells, can function as central electric power stations, converting sunlight into electrical energy for distribution to industrial, commercial, and residential users. Solar cells in much smaller configurations, commonly referred to as solar cell panels or simply solar panels, have been installed by homeowners on their rooftops to replace or augment their conventional electric supply. Solar cell panels also are used to provide electric power in many remote terrestrial locations where conventional electric power sources are either unavailable or prohibitively expensive to install. Because they have no moving parts that could need maintenance or fuels that would require replenishment, solar cells provide power for most space installations, from communications and weather satellites to space stations (space station). (Solar power is insufficient for space probes sent to the outer planets of the solar system or into interstellar space (interstellar medium), however, because of the diffusion of radiant energy with distance from the Sun.) Another growing application of solar cells is in consumer products, such as electronic toys, handheld calculators, and portable radios. Solar cells used in devices of this kind may utilize artificial light (e.g., from incandescent and fluorescent lamps) as well as sunlight.While total photovoltaic energy production is minuscule, it is likely to increase as fossil fuel resources shrink. In fact, the world's current energy consumption could be supplied by covering less than 1 percent of the Earth's surface with solar panels. The material requirements would be enormous but feasible, as silicon is the second most abundant element in the Earth's crust. These factors have led solar proponents to envision a future “solar economy” in which practically all of humanity's energy requirements are satisfied by cheap, clean, renewable sunlight.

Solar cell structure and operation

Solar cells, whether used in a central power station, a satellite (Earth satellite), or a calculator, have the same basic structure, as shown in the figure-->

Solar cells, whether used in a central power station, a satellite (Earth satellite), or a calculator, have the same basic structure, as shown in the figure--> . Light enters the device through an optical coating, or antireflection layer, that minimizes the loss of light by reflection; it effectively traps the light falling on the solar cell by promoting its transmission to the energy-conversion layers below. The antireflection layer is typically an oxide of silicon, tantalum, or titanium that is formed on the cell surface by spin-coating or a vacuum deposition technique.

. Light enters the device through an optical coating, or antireflection layer, that minimizes the loss of light by reflection; it effectively traps the light falling on the solar cell by promoting its transmission to the energy-conversion layers below. The antireflection layer is typically an oxide of silicon, tantalum, or titanium that is formed on the cell surface by spin-coating or a vacuum deposition technique.The three energy-conversion layers below the antireflection layer are the top junction layer, the absorber layer, which constitutes the core of the device, and the back junction layer. Two additional electrical contact layers are needed to carry the electric current out to an external load and back into the cell, thus completing an electric circuit. The electrical contact layer on the face of the cell where light enters is generally present in some grid pattern and is composed of a good conductor such as a metal. Since metal blocks light, the grid lines are as thin and widely spaced as is possible without impairing collection of the current produced by the cell. The back electrical contact layer has no such diametrically opposed restrictions. It need simply function as an electrical contact and thus covers the entire back surface of the cell structure. Because the back layer also must be a very good electrical conductor, it is always made of metal.

Since most of the energy in sunlight and artificial light is in the visible range of electromagnetic radiation, a solar cell absorber should be efficient in absorbing radiation at those wavelengths. Materials that strongly absorb visible radiation belong to a class of substances known as semiconductors (semiconductor). Semiconductors in thicknesses of about one-hundredth of a centimetre or less can absorb all incident visible light; since the junction-forming and contact layers are much thinner, the thickness of a solar cell is essentially that of the absorber. Examples of semiconductor materials employed in solar cells include silicon, gallium arsenide, indium phosphide, and copper indium selenide.

When light falls on a solar cell, electrons in the absorber layer are excited from a lower-energy “ground state,” in which they are bound to specific atoms in the solid, to a higher “excited state,” in which they can move through the solid. In the absence of the junction-forming layers, these “free” electrons are in random motion, and so there can be no oriented direct current. The addition of junction-forming layers, however, induces a built-in electric field that produces the photovoltaic effect. In effect, the electric field gives a collective motion to the electrons that flow past the electrical contact layers into an external circuit where they can do useful work.

The materials used for the two junction-forming layers must be dissimilar to the absorber in order to produce the built-in electric field and to carry the electric current. Hence, these may be different semiconductors (or the same semiconductor with different types of conduction), or they may be a metal and a semiconductor. The materials used to construct the various layers of solar cells are essentially the same as those used to produce the diodes and transistors of solid-state electronics and microelectronics (see also electronics: Optoelectronics (electronics)). Solar cells and microelectronic devices share the same basic technology. In solar cell fabrication, however, one seeks to construct a large-area device because the power produced is proportional to the illuminated area. In microelectronics the goal is, of course, to construct electronic components of ever smaller dimensions in order to increase their density and operating speed within semiconductor chips, or integrated circuits (integrated circuit).

The photovoltaic process bears certain similarities to photosynthesis, the process by which the energy in light is converted into chemical energy in plants. Since solar cells obviously cannot produce electric power in the dark, part of the energy they develop under light is stored, in many applications, for use when light is not available. One common means of storing this electrical energy is by charging electrochemical storage batteries. This sequence of converting the energy in light into the energy of excited electrons and then into stored chemical energy is strikingly similar to the process of photosynthesis.

Solar panel design

Most solar cells are a few square centimetres in area and protected from the environment by a thin coating of glass or transparent plastic (see figure-->

Most solar cells are a few square centimetres in area and protected from the environment by a thin coating of glass or transparent plastic (see figure--> ). Because a typical 10 cm × 10 cm (4 inch × 4 inch) solar cell generates only about two watts of electrical power (15 to 20 percent of the energy of light incident on their surface), cells are usually combined in series to boost the voltage or in parallel to increase the current. A solar, or photovoltaic (PV), module generally consists of 36 interconnected cells laminated to glass within an aluminum frame. In turn, one or more of these modules may be wired and framed together to form a solar panel. Solar panels are slightly less efficient at energy conversion per surface area than individual cells, because of inevitable inactive areas in the assembly and cell-to-cell variations in performance. The back of each solar panel is equipped with standardized sockets so that its output can be combined with other solar panels to form a solar array. A complete photovoltaic system may consist of many solar panels, a power system for accommodating different electrical loads, an external circuit, and storage batteries. Photovoltaic systems are broadly classifiable as either stand-alone or grid-connected systems.

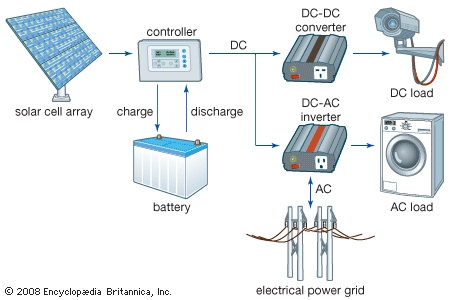

). Because a typical 10 cm × 10 cm (4 inch × 4 inch) solar cell generates only about two watts of electrical power (15 to 20 percent of the energy of light incident on their surface), cells are usually combined in series to boost the voltage or in parallel to increase the current. A solar, or photovoltaic (PV), module generally consists of 36 interconnected cells laminated to glass within an aluminum frame. In turn, one or more of these modules may be wired and framed together to form a solar panel. Solar panels are slightly less efficient at energy conversion per surface area than individual cells, because of inevitable inactive areas in the assembly and cell-to-cell variations in performance. The back of each solar panel is equipped with standardized sockets so that its output can be combined with other solar panels to form a solar array. A complete photovoltaic system may consist of many solar panels, a power system for accommodating different electrical loads, an external circuit, and storage batteries. Photovoltaic systems are broadly classifiable as either stand-alone or grid-connected systems.Stand-alone systems contain a solar array and a bank of batteries directly wired to an application or load circuit. A battery system is essential to compensate for the absence of any electrical output from the cells at night or in overcast conditions; this adds considerably to the overall cost. Each battery stores direct current (DC) electricity at a fixed voltage determined by the panel specifications, although load requirements may differ. DC-to-DC converters are used to provide the voltage levels demanded by DC loads, and DC-to-AC inverters supply power to alternating current (AC) loads. Stand-alone systems are ideally suited for remote installations where linking to a central power station is prohibitively expensive. Examples include pumping water for feedstock and providing electric power to lighthouses, telecommunications repeater stations, and mountain lodges.

Grid-connected systems integrate solar arrays with public utility power grids in two ways. One-way systems are used by utilities to supplement power grids during midday peak usage. Bidirectional systems are used by companies and individuals to supply some or all of their power needs, with any excess power fed back into a utility power grid. A major advantage of grid-connected systems is that no storage batteries are needed. The corresponding reduction in capital and maintenance costs is offset, however, by the increased complexity of the system. Inverters and additional protective gear are needed to interface low-voltage DC output from the solar array with a high-voltage AC power grid. Additionally, rate structures for reverse metering are necessary when residential and industrial solar systems feed energy back into a utility grid.

Grid-connected systems integrate solar arrays with public utility power grids in two ways. One-way systems are used by utilities to supplement power grids during midday peak usage. Bidirectional systems are used by companies and individuals to supply some or all of their power needs, with any excess power fed back into a utility power grid. A major advantage of grid-connected systems is that no storage batteries are needed. The corresponding reduction in capital and maintenance costs is offset, however, by the increased complexity of the system. Inverters and additional protective gear are needed to interface low-voltage DC output from the solar array with a high-voltage AC power grid. Additionally, rate structures for reverse metering are necessary when residential and industrial solar systems feed energy back into a utility grid.The simplest deployment of solar panels is on a tilted support frame or rack known as a fixed mount. For maximum efficiency, a fixed mount should face south in the Northern Hemisphere or north in the Southern Hemisphere, and it should have a tilt angle from horizontal of about 15 degrees less than the local latitude in summer and 25 degrees more than the local latitude in winter. More complicated deployments involve motor-driven tracking systems that continually reorient the panels to follow the daily and seasonal movements of the Sun. Such systems are justified only for large-scale utility generation using high-efficiency concentrator solar cells with lenses or parabolic mirrors that can intensify solar radiation a hundredfold or more.

Although sunlight is free, the cost of materials and available space must be considered in designing a solar system; less-efficient solar panels imply more panels, occupying more space, in order to produce the same amount of electricity. Compromises between cost of materials and efficiency are particularly evident for space-based solar systems. Panels used on satellites have to be extra-rugged, reliable, and resistant to radiation damage encountered in the Earth's upper atmosphere. In addition, minimizing the liftoff weight of these panels is more critical than fabrication costs. Another factor in solar panel design is the ability to fabricate cells in “thin-film” form on a variety of substrates, such as glass, ceramic, and plastic, for more flexible deployment. Amorphous silicon is very attractive from this viewpoint. In particular, amorphous silicon-coated roof tiles and other photovoltaic materials have been introduced in architectural design and for recreational vehicles, boats, and automobiles.

Development of solar cells

The development of solar cell technology stems from the work of the French physicist Antoine-César Becquerel in 1839. Becquerel discovered the photovoltaic effect while experimenting with a solid electrode in an electrolyte solution; he observed that voltage developed when light fell upon the electrode. About 50 years later, Charles Fritts constructed the first true solar cells using junctions formed by coating the semiconductor selenium with an ultrathin, nearly transparent layer of gold. Fritts's devices were very inefficient converters of energy; they transformed less than 1 percent of absorbed light energy into electrical energy. Though inefficient by today's standards, these early solar cells fostered among some a vision of abundant, clean power. In 1891 R. Appleyard wrote of

the blessed vision of the Sun, no longer pouring his energies unrequited into space, but by means of photo-electric cells…, these powers gathered into electrical storehouses to the total extinction of steam engines, and the utter repression of smoke.

By 1927 another metal-semiconductor-junction solar cell, in this case made of copper and the semiconductor copper oxide, had been demonstrated. By the 1930s both the selenium cell and the copper oxide cell were being employed in light-sensitive devices, such as photometers, for use in photography. These early solar cells, however, still had energy-conversion efficiencies of less than 1 percent. This impasse was finally overcome with the development of the silicon solar cell by Russell Ohl in 1941. Thirteen years later, aided by the rapid commercialization of silicon technology needed to fabricate the transistor, three other American researchers—Gerald Pearson, Daryl Chapin, and Calvin Fuller—demonstrated a silicon solar cell capable of a 6 percent energy-conversion efficiency when used in direct sunlight. By the late 1980s silicon cells, as well as cells made of gallium arsenide, with efficiencies of more than 20 percent had been fabricated. In 1989 a concentrator solar cell in which sunlight was concentrated onto the cell surface by means of lenses achieved an efficiency of 37 percent owing to the increased intensity of the collected energy. By connecting cells of different semiconductors optically and electrically in series, even higher efficiencies are possible, but at increased cost and added complexity. In general, solar cells of widely varying efficiencies and cost are now available.

Additional Reading

Paul D. Maycock and Edward N. Stirewalt, Photovoltaics: Sunlight to Electricity in One Step (1981), is a nontechnical work. Richard J. Komp, Practical Photovoltaics: Electricity from Solar Cells, 3rd ed. rev. (2001); and Kenneth Zweibel and Paul Hersch, Basic Photovoltaic Principles and Methods (1984), are more advanced but still accessible to the non-technically-trained reader and contain much practical information. Stephen J. Fonash, Solar Cell Device Physics (1981); and Alan L. Fahrenbruch and Richard H. Bube, Fundamentals of Solar Cells (1983), are for device specialists. Roger A. Messenger and Jerry Ventre, Photovoltaic Systems Engineering, 2nd ed. (2004), is for systems and applications specialists.

- Indianista novel

- Indian languages

- Indian law

- Indian literature

- Indian Museum

- Indian Mutiny

- Indian National Congress

- Indian National Trade Union Congress

- Indian Ocean

- Indian Ocean tsunami

- Indianola

- Indian paint brush

- Indian philosophy

- Indian pipe

- Indian Removal Act

- Indian Reorganization Act

- Indian sculpture

- Indian Shaker Church

- Indian summer

- Indian Territory

- Indian tobacco

- India rubber plant

- indicator species

- indiction

- indictment