connective tissue

Introduction

group of tissues in the body that maintains the form of the body and its organs and provides cohesion and internal support. The connective tissues include several types of fibrous tissue that vary only in their density and cellularity, as well as the more specialized and recognizable variants— bone, ligaments (ligament), tendons (tendon), cartilage, and adipose (fat) tissue.

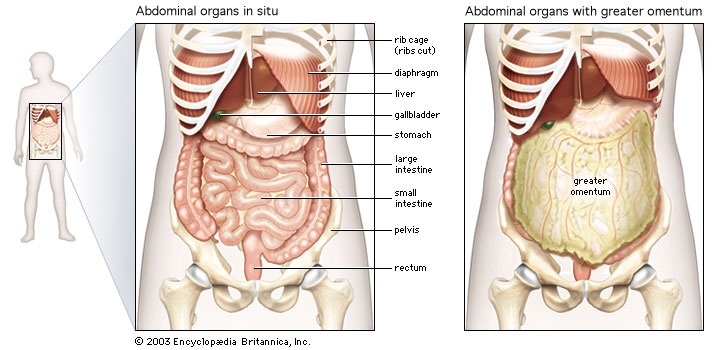

group of tissues in the body that maintains the form of the body and its organs and provides cohesion and internal support. The connective tissues include several types of fibrous tissue that vary only in their density and cellularity, as well as the more specialized and recognizable variants— bone, ligaments (ligament), tendons (tendon), cartilage, and adipose (fat) tissue. Some organs are suspended from the wall of a body cavity by thin sheets of connective tissue called mesenteries (mesentery); others are embedded in adipose tissue, a form of connective tissue in which the cells are specialized for the synthesis and storage of energy-rich reserves of fat, or lipid. The entire body is supported from within by a skeleton composed of bone, a type of connective tissue endowed with great resistance to stress owing to its highly ordered laminated structure and to its hardness, which results from deposition of mineral salts in its fibres and amorphous matrix. The individual bones of the skeleton are held firmly together by ligaments (ligament), and muscles (muscle) are attached to bone by tendons, both of which are examples of dense connective tissue in which many fibre bundles are associated in parallel array to provide great tensile strength. At joints (joint), the articular surfaces of the bones are covered with cartilage, a connective tissue with an abundant intercellular substance that gives it a firm consistency well adapted to permitting smooth gliding movements between the apposed surfaces. The synovial membrane, which lines the margins of the joint cavity and lubricates and nourishes the joint surfaces, is also a form of connective tissue.

Some organs are suspended from the wall of a body cavity by thin sheets of connective tissue called mesenteries (mesentery); others are embedded in adipose tissue, a form of connective tissue in which the cells are specialized for the synthesis and storage of energy-rich reserves of fat, or lipid. The entire body is supported from within by a skeleton composed of bone, a type of connective tissue endowed with great resistance to stress owing to its highly ordered laminated structure and to its hardness, which results from deposition of mineral salts in its fibres and amorphous matrix. The individual bones of the skeleton are held firmly together by ligaments (ligament), and muscles (muscle) are attached to bone by tendons, both of which are examples of dense connective tissue in which many fibre bundles are associated in parallel array to provide great tensile strength. At joints (joint), the articular surfaces of the bones are covered with cartilage, a connective tissue with an abundant intercellular substance that gives it a firm consistency well adapted to permitting smooth gliding movements between the apposed surfaces. The synovial membrane, which lines the margins of the joint cavity and lubricates and nourishes the joint surfaces, is also a form of connective tissue.Blood vessels (blood vessel), both large and small, course through connective tissue, which is therefore closely associated with the nourishment of tissues and organs throughout the body. All nutrient materials and waste products exchanged between the organs and the blood must traverse perivascular spaces occupied by connective tissue. One of the important functions of the connective-tissue cells is to maintain conditions in the extracellular spaces that favour this exchange.

Components of connective tissue

All forms of connective tissue are composed of (1) extracellular fibres, (2) an amorphous matrix called ground substance, and (3) stationary and migrating cells. The proportions of these components vary from one part of the body to another depending on the local structural requirements. In some areas, the connective tissue is loosely organized and highly cellular; in others, its fibrous components predominate; and in still others, the ground substance may be its most conspicuous feature. The anatomical classification of the various types of connective tissue is based largely upon the relative abundance and arrangement of these components.

Extracellular fibres

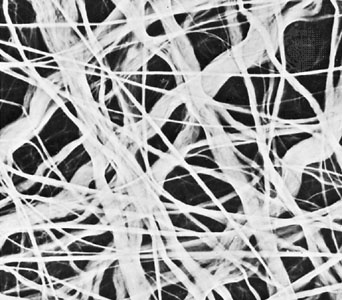

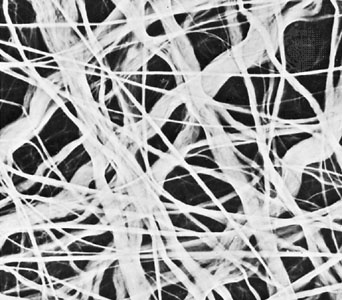

The fibrous components are of three kinds: collagenous, elastic, and reticular. Most abundant are the fibres composed of the protein collagen. The fibrous components of loose areolar connective tissue, when viewed with the light microscope, appear as colourless strands of varying diameter running in all directions, and, if not under tension, these have a slightly undulant course. At high magnification, the larger strands are seen to be made up of bundles of smaller fibres. The smallest fibres visible with the light microscope can be shown with the electron microscope to be composed of multiple fibrils up to 1000 angstroms (one Å = 1 × 10−7 mm) in diameter. These unit fibrils are cross-striated with transverse bands repeating every 640 Å along their length.

The fibrous components are of three kinds: collagenous, elastic, and reticular. Most abundant are the fibres composed of the protein collagen. The fibrous components of loose areolar connective tissue, when viewed with the light microscope, appear as colourless strands of varying diameter running in all directions, and, if not under tension, these have a slightly undulant course. At high magnification, the larger strands are seen to be made up of bundles of smaller fibres. The smallest fibres visible with the light microscope can be shown with the electron microscope to be composed of multiple fibrils up to 1000 angstroms (one Å = 1 × 10−7 mm) in diameter. These unit fibrils are cross-striated with transverse bands repeating every 640 Å along their length.Collagen is of commercial as well as medical interest, because leather is the dense collagen of the dermis of animal skins preserved and toughened by the process called tanning. Fresh collagen dissolves in hot water, and the product is gelatin. Under appropriate conditions, collagen can be brought into solution without chemical change. The fundamental units in such solutions are slender tropocollagen molecules about 14 Å wide and 2800 Å long. Collagen appears to be secreted in this form by the connective-tissue cells called fibrocytes, and the tropocollagen molecules assemble extracellularly to form striated collagen fibrils. By an alteration of the physicochemical conditions, tropocollagen in solution can be induced to polymerize with the formation of cross-striated fibrils identical to native collagen, thus simulating in the test tube the process of assembly that is believed to take place during fibrogenesis in the living organism. Analysis of the structure of collagen by X-ray diffraction has shown that the tropocollagen molecule consists of three side-by-side polypeptide chains—linear combinations of a number of amino acids (amino acid), which are subunits of proteins—each in the form of a left-handed helix. These three left-handed helices are further twisted around one another to form a major right-handed helix. Upon chemical analysis, the amino acid composition of collagen is found to be unique in its extremely high proline content (22 percent) and in the fact that one-third of the amino acid residues are glycine. It is the only naturally occurring protein known to contain hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine. Two of the three polypeptide chains comprising the tropocollagen molecule are similar in amino acid composition, while the third is distinctly different. In the tissues, the collagen fibrils are believed to be held together by a polysaccharide component that has not been fully characterized.

Elastic fibres (elastic fibre) are composed of the protein elastin and differ from collagenous fibres in dimensions, pattern, and chemical composition. They do not have uniform subunits comparable to the unit fibrils of collagen. They present a variable appearance in electron micrographs; sometimes they appear to have an amorphous core surrounded by minute fibrils, while in other sites they appear to consist exclusively of dense amorphous material. Whether there are in fact two components or whether these are differing forms of the same substance is not yet clear. At the light-microscope level, the fibres vary in diameter and often branch and reunite to form extensive networks in loose connective tissue. When present in high concentration, they impart a yellow colour to the tissue. In elastic ligaments, the fibres are very coarse and are arranged in parallel bundles. In the walls of arteries, elastin is present in the form of sheets or membranes perforated by openings of varying size. Elastic fibres are extremely resistant to hot water, to strong alkali, and even to digestion with the proteolytic enzyme trypsin. They can be digested, however, by a specific enzyme, elastase, present in the pancreas. Upon chemical analysis, elastin, like collagen, is found to be rich in glycine and proline, but it differs in its high content of valine and in the presence of an unusual amino acid, desmosine. As their name implies, elastic fibres are highly distensible and, when broken, recoil like rubber bands. Changes in this property and diminution in their numbers are thought to be, in part, responsible for the loss of elasticity of the skin and of the blood-vessel walls in old age.

Elastic fibres (elastic fibre) are composed of the protein elastin and differ from collagenous fibres in dimensions, pattern, and chemical composition. They do not have uniform subunits comparable to the unit fibrils of collagen. They present a variable appearance in electron micrographs; sometimes they appear to have an amorphous core surrounded by minute fibrils, while in other sites they appear to consist exclusively of dense amorphous material. Whether there are in fact two components or whether these are differing forms of the same substance is not yet clear. At the light-microscope level, the fibres vary in diameter and often branch and reunite to form extensive networks in loose connective tissue. When present in high concentration, they impart a yellow colour to the tissue. In elastic ligaments, the fibres are very coarse and are arranged in parallel bundles. In the walls of arteries, elastin is present in the form of sheets or membranes perforated by openings of varying size. Elastic fibres are extremely resistant to hot water, to strong alkali, and even to digestion with the proteolytic enzyme trypsin. They can be digested, however, by a specific enzyme, elastase, present in the pancreas. Upon chemical analysis, elastin, like collagen, is found to be rich in glycine and proline, but it differs in its high content of valine and in the presence of an unusual amino acid, desmosine. As their name implies, elastic fibres are highly distensible and, when broken, recoil like rubber bands. Changes in this property and diminution in their numbers are thought to be, in part, responsible for the loss of elasticity of the skin and of the blood-vessel walls in old age.Reticular fibres (reticular fibre) are distinguished by their tendency to form fine-meshed networks around cells and cell groups and by virtue of their property of staining black, because of adsorption of metallic silver, when they are treated with alkaline solutions of reducible silver salts. They were formerly believed to be composed of a distinct protein, reticulin, but electron microscopy has revealed that reticular fibres are small fascicles of typical collagen fibrils interwoven to form a network. It is now apparent that reticular fibres are simply a form of collagen, and their distinctive staining depends upon the mode of association of the fibrils and possibly upon subtle differences in their relation to the polysaccharide material that binds them together.

ground substance

The amorphous ground substance of connective tissue is a transparent material with the properties of a viscous solution or a highly hydrated thin gel. Its principal constituents are large carbohydrate molecules or complexes of protein and carbohydrate, called glycosaminoglycans (formerly known as mucopolysaccharides). One of these carbohydrates is hyaluronic acid, composed of glucuronic acid and an amino sugar, N-acetyl glucosamine. Other carbohydrates of the connective tissue are chondroitin-4-sulfate (chondroitin sulfate A) and chondroitin-6-sulfate (chondroitin sulfate C). The sugars of the sulfates are galactosamine and glucuronate. Multiple chains of chondroitin sulfate seem to be bound to protein. These substances in solution are viscous. All substances passing to and from cells must pass through the ground substance. Variations in its composition and viscosity may therefore have an important influence on the exchange of materials between tissue cells and the blood. Its physical consistency also constitutes a barrier to the spread of particulates introduced into the tissues. It is interesting, in this relation, that some bacteria produce an enzyme, hyaluronidase, which breaks up hyaluronic acid into subunits and alters the viscosity of ground substance. The ability of these bacteria to produce this enzyme is probably responsible for their invasiveness in the tissues.

Cells of connective tissue

The cells of connective tissue include two types that are relatively stationary—fibrocytes and adipose cells—and several types of motile migrating cells—mast cells, macrophages, monocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils.

All the cells of connective tissue develop during embryonic life from the mesenchyme, a network of primitive stellate cells that have the potential for differentiating along several different lines depending upon local conditions. In addition to the specialized cell types of adult connective tissue described below, it is believed that small numbers of mesenchymal cells (stem cells (stem cell)) persist into postnatal life in the walls of small blood vessels (blood vessel) and elsewhere and that these retain the capacity to differentiate into fibrocytes, adipose cells, macrophages, or a multitude of other cell types as the need arises.

Stationary cells

The ubiquitous fibrocytes are the principal cells of connective tissue, occurring as long spindle-shaped cells stretched along bundles of collagen fibrils. Their function is to secrete tropocollagen and constituents of the ground substance and to maintain these extracellular tissue components. When organs are injured, the fibrocytes of the stroma are stimulated to proliferate and become fibroblasts (fibroblast); fibroblasts migrate into the defect and deposit an abundance of new collagen, which forms a fibrous scar.

Adipose (adipose cell), or fat, cells are connective-tissue cells that are specialized for the synthesis and storage of reserve nutrients. They receive glucose and fatty acids from the blood and convert them to lipid, which accumulates in the body of the cell as a large oil droplet. This distends the cell and imposes upon it a spherical form. The nucleus is displaced to the periphery, and other metabolically active constituents of the cell are confined to a thin rim of cytoplasm around the large central droplet of lipid. Adipose cells may occur in small numbers anywhere in connective tissue, but they tend to develop preferentially along the course of small blood vessels. Where they accumulate in such large numbers that they become the predominant cellular element, they constitute the fat or adipose tissue of the body.

Migrating cells

In addition to the relatively fixed cell types described above, there are free cells that reside in the interstices of loose connective tissue. These vary in their abundance and are free to migrate through the extracellular spaces. Among these wandering cells are the mast cells (mast cell); these have a cell body filled with coarse granules that contain two biologically active substances, histamine and heparin. Histamine affects vascular permeability, and heparin, when added to blood, delays or prevents its clotting. Mast cells respond to mechanical or chemical irritation by discharging varying numbers of their granules. Histamine released from them causes fluid to escape from neighbouring capillaries or venules; this results in local swelling, as seen in the welt that appears around an insect bite.

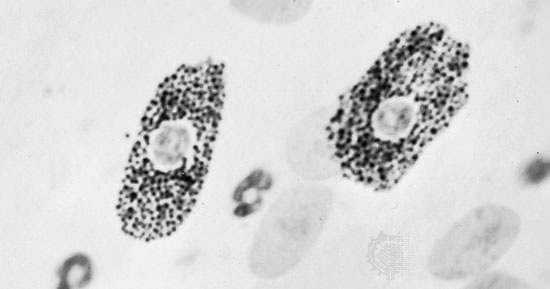

In addition to the relatively fixed cell types described above, there are free cells that reside in the interstices of loose connective tissue. These vary in their abundance and are free to migrate through the extracellular spaces. Among these wandering cells are the mast cells (mast cell); these have a cell body filled with coarse granules that contain two biologically active substances, histamine and heparin. Histamine affects vascular permeability, and heparin, when added to blood, delays or prevents its clotting. Mast cells respond to mechanical or chemical irritation by discharging varying numbers of their granules. Histamine released from them causes fluid to escape from neighbouring capillaries or venules; this results in local swelling, as seen in the welt that appears around an insect bite.Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell, or leukocyte. Some of these migrate through the walls of capillaries and take up residence in the connective tissues. They have polymorphous nuclei and, in the cell substance outside the nuclei, coarse granules that stain with eosin and other acid dyes. In electron micrographs, the granules contain conspicuous crystals. The granules have been isolated and shown to contain a variety of hydrolytic enzymes. Eosinophils are normally widespread in connective tissues of the body, but they are especially abundant in persons suffering from allergic diseases. The cells are believed to phagocytose and break down antigen-antibody complexes.

plasma cells are mature antibody-secreting lymphocytes (lymphocyte) that are present in limited numbers in loose connective tissues and in larger numbers in lymphoid tissue. Lymphocytes are a type of leukoctye that is able to recognize foreign proteins and to respond to their presence by proliferating and differentiating into plasma cells. The plasma cells in turn synthesize and release specific immunoglobulins, called antibodies (antibody), that combine with and neutralize the foreign proteins. Lymphocytes (lymphocyte) are among the normal cellular elements of the blood, but they may also leave the blood and migrate in the connective tissues. They constitute an important reserve of relatively undifferentiated cells capable of sustaining an immunological response.

Another of the leukocytes that enter the connective tissues from the blood is the monocyte, a mononuclear cell larger than the lymphocyte and with different potentialities. These migratory cells can divide and, when appropriately stimulated, can transform into highly phagocytic macrophages. The reaction of the blood and connective-tissue cells to injury is called inflammation and is usually accompanied by local heat, swelling, redness, and pain. Under these conditions, the neutrophilic leukocytes (white blood cells called neutrophilic because of their neutral staining characteristics with certain dyes), which are not normally present in connective tissue in significant numbers, may migrate through the capillary walls in astronomical numbers and join the macrophages in the work of ingesting and destroying bacteria. Voraciously phagocytic, the neutrophils have a short life span; having accomplished their mission, they die in great numbers. pus, which may accumulate at sites of acute inflammation, is composed largely of dead and dying neutrophilic leukocytes.

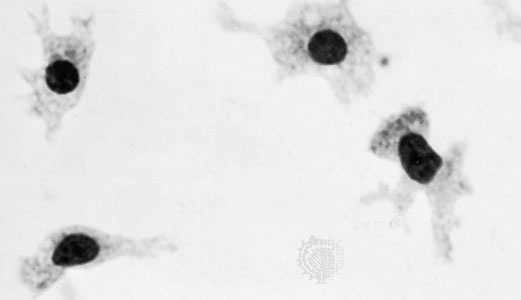

The macrophages, or histiocytes, are derived from circulating monocytes in the bloodstream; they are also important for tissue repair and for defense against bacterial invasion. They have a great capacity for phagocytosis—the process by which cells engulf cellular debris, bacteria, or other foreign matter and break them down by intracellular digestion. Thus, they represent an important force of mobile scavenger cells.

The macrophages, or histiocytes, are derived from circulating monocytes in the bloodstream; they are also important for tissue repair and for defense against bacterial invasion. They have a great capacity for phagocytosis—the process by which cells engulf cellular debris, bacteria, or other foreign matter and break them down by intracellular digestion. Thus, they represent an important force of mobile scavenger cells.Types of connective tissue

The description presented thus far applies to the widely distributed loose areolar connective tissue, which is relatively unspecialized and can therefore be considered prototypic. In the more specialized forms of connective tissues, one component or another may predominate over all the others, depending upon the local structural or metabolic requirements.

Adipose tissue, for example, is a variant of loose areolar tissue in which large numbers of adipose cells make up the bulk of the tissue.

Dense fibrous connective tissue is composed of closely packed bundles of collagen and their associated fibrocytes, but there are relatively few elastic fibres and little ground substance. The term irregular dense fibrous tissue is applied to sites where the collagen bundles are randomly oriented and interwoven, as in the dermis of the skin and the capsules of joints. Regular dense fibrous tissue is the term used to describe tendons (tendon), ligaments, and aponeuroses (aponeurosis) (fibrous sheets that form attachments for muscles), where the collagen fibres are precisely oriented in parallel bundles.

Dense fibrous connective tissue is composed of closely packed bundles of collagen and their associated fibrocytes, but there are relatively few elastic fibres and little ground substance. The term irregular dense fibrous tissue is applied to sites where the collagen bundles are randomly oriented and interwoven, as in the dermis of the skin and the capsules of joints. Regular dense fibrous tissue is the term used to describe tendons (tendon), ligaments, and aponeuroses (aponeurosis) (fibrous sheets that form attachments for muscles), where the collagen fibres are precisely oriented in parallel bundles.The synovial (synovial tissue) membrane, which lines joint capsules, is composed of loose vascular connective tissue but has cells specialized for secretion of the viscous synovial fluid, which is rich in hyaluronic acid, and for phagocytic functions. This fluid serves as a lubricant and nutrient for the avascular joint surfaces. Similar tissue forms sheaths around tendons where they pass over bony prominences.

cartilage

cartilage is a form of connective tissue in which the ground substance is abundant and of a firmly gelated consistency that endows this tissue with unusual rigidity and resistance to compression. The cells of cartilage, called chondrocytes, are isolated in small lacunae within the matrix. Although cartilage is avascular, gaseous metabolites and nutrients can diffuse through the aqueous phase of the gel-like matrix to reach the cells. Cartilage is enclosed by the perichondrium, a dense fibrous layer lined by cells that have the capacity to secrete hyaline matrix. Cartilage grows by formation of additional matrix and incorporation of new cells from the inner chondrogenic layer of the perichondrium. In addition, the young chondrocytes retain the capacity to divide even after they become isolated in lacunae within the matrix. The daughter cells of these divisions secrete new matrix between them and move apart in separate lacunae. The capacity of cartilage for both appositional and interstitial growth makes it a favourable material for the skeleton of the rapidly growing embryo. The cartilaginous skeletal elements present in fetal life are subsequently replaced by bone.

Hyaline cartilage, the most widely distributed form, has a pearl-gray semitranslucent matrix containing randomly oriented collagen fibrils but relatively little elastin. It is normally found on surfaces of joints and in the cartilage making up the fetal skeleton. In elastic cartilage, on the other hand, the matrix has a pale yellow appearance owing to the abundance of elastic fibres embedded in its substance. This variant of cartilage is more flexible than hyaline cartilage and is found principally in the external ear and in the larynx and epiglottis. The third type, called fibrocartilage, has a large proportion of dense collagen bundles oriented parallel. Its cells occupy lacunae that are often arranged in rows between the coarse bundles of collagen. It is found in intervertebral disks, at sites of attachment of tendons to bone, and in the articular disks of certain joints. Any cartilage type may have foci of calcification.

Bone

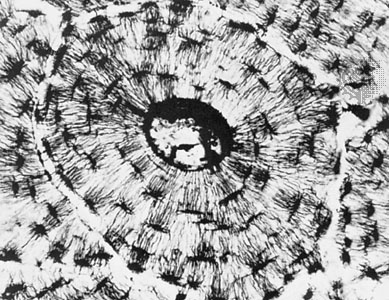

Like other connective tissues, bone consists of cells, fibres, and ground substance, but, in addition, the extracellular components are impregnated with minute crystals of calcium phosphate in the form of the mineral hydroxyapatite (hydroxylapatite). The mineralization of the matrix is responsible for the hardness of bone. It also provides a large reserve of calcium that can be drawn upon to meet unusual needs for this element elsewhere in the body. The structural organization of bone is adapted to give maximal strength for its weight-bearing function with minimum weight. There are bones strong enough to support the weight of an elephant and others light enough to give internal support and leverage to the wings of birds.

Like other connective tissues, bone consists of cells, fibres, and ground substance, but, in addition, the extracellular components are impregnated with minute crystals of calcium phosphate in the form of the mineral hydroxyapatite (hydroxylapatite). The mineralization of the matrix is responsible for the hardness of bone. It also provides a large reserve of calcium that can be drawn upon to meet unusual needs for this element elsewhere in the body. The structural organization of bone is adapted to give maximal strength for its weight-bearing function with minimum weight. There are bones strong enough to support the weight of an elephant and others light enough to give internal support and leverage to the wings of birds.Additional Reading

Additional information on connective tissues may be found in Don W. Fawcett, A Textbook of Histology, 12th ed. (1994), chapter 5, pp. 133–169; Emanuel Rubin and John L. Farber (eds.), Pathology, 3rd ed. (1999), chapter 3, pp. 76–103, and chapter 26, pp. 1336–1413; and in Arthur W. Ham and David H. Cormack, Ham's Histology, 9th ed. (1987), chapter 7, pp. 155–187.

- Marian Wright Edelman

- Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska

- Maria Polidoúri

- Marias River

- Maria Stella

- Maria Susanna Cummins

- Maria Tallchief

- Maria Theresa

- Maria Theresa Kemble

- Maria Walewska

- Maria Weston Chapman

- Mariazell

- Maribo

- Maribor

- Marichal, Juan Antonio

- Marie Adelaide Lowndes

- Marie-Amélie de Bourbon

- Marie-Anne de la Trémoille, princesse des Ursins

- Marie-Anne de la Trémoille Ursins, princesse des

- Marie-Anne de Mailly-Nesle Châteauroux, Duchess de

- Marie-Anne de Mailly-Nesle, Duchess de Châteauroux

- Marie-Antoine Carême

- Marie-Antoinette

- Marie, Baroness (Freifrau) von Ebner-Eschenbach

- Marie Bashkirtseff