Coolidge, Calvin

president of United States

in full John Calvin Coolidge

born July 4, 1872, Plymouth, Vermont, U.S.

died January 5, 1933, Northampton, Massachusetts

30th president of the United States (1923–29). Coolidge acceded to the presidency after the death in office of Warren G. Harding (Harding, Warren G.), just as the Harding scandals were coming to light. He restored integrity to the executive branch of the federal government while continuing the conservative pro-business policies of his predecessor. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)

30th president of the United States (1923–29). Coolidge acceded to the presidency after the death in office of Warren G. Harding (Harding, Warren G.), just as the Harding scandals were coming to light. He restored integrity to the executive branch of the federal government while continuing the conservative pro-business policies of his predecessor. (For a discussion of the history and nature of the presidency, see presidency of the United States of America.)Coolidge was the only son of John Calvin Coolidge and Victoria Moor Coolidge. His father, whose forebears had immigrated to America about 1630, was a storekeeper who instilled in his son the New England Puritan virtues—honesty, industry, thrift, taciturnity, and piety—while his mother cultivated in him a love of nature and books. A graduate of Amherst College, Coolidge began practicing law in 1897. In 1905 he married Grace Anna Goodhue, a teacher in the Clarke Institute for the Deaf, with whom he had two sons.

A Republican, Coolidge entered politics as a city councilman in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1898. He was elected mayor of Northampton in 1909 and then served in the Massachusetts state government as senator (1911–15) and lieutenant governor (1915–18). Elected governor in 1918, Coolidge captured national attention the following year when he called out the state guard to quell violence and disorder resulting from a strike by the Boston police, who had formed a labour union to press their demands for better pay and working conditions. When labour leaders called on him to support their demands for reinstatement of police officers who had been fired for striking, Coolidge refused, summing up his reasoning in a single sentence that reverberated throughout the country: “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”

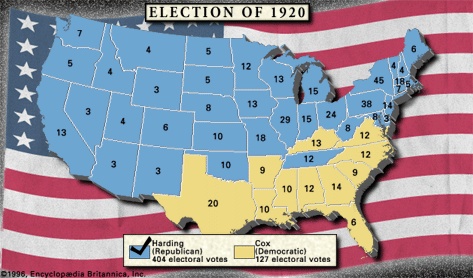

That statement—combined with Coolidge's strong stand against the Boston police at a time when many Americans viewed organized labour as too radical—catapulted Coolidge onto the Republican Party's ticket in 1920 as Harding's vice-presidential running mate. The personality of the taciturn Coolidge could not have provided a greater contrast to that of the gregarious Harding. In terms of policy, however, Harding and Coolidge were nearly identical. Both were members of the Old Guard Republicans, that conservative segment of the party that had remained with President William Howard Taft (Taft, William Howard) in 1912 when Theodore Roosevelt left to form the Bull Moose Party. Promising the American people a “return to normalcy,” Harding and Coolidge achieved the greatest popular vote margin in presidential elections to that time, crushing the Democratic ticket of James Cox (Cox, James M) and Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Franklin D.) by 60 to 34 percent. The electoral vote was equally one-sided: 404 to 127.

That statement—combined with Coolidge's strong stand against the Boston police at a time when many Americans viewed organized labour as too radical—catapulted Coolidge onto the Republican Party's ticket in 1920 as Harding's vice-presidential running mate. The personality of the taciturn Coolidge could not have provided a greater contrast to that of the gregarious Harding. In terms of policy, however, Harding and Coolidge were nearly identical. Both were members of the Old Guard Republicans, that conservative segment of the party that had remained with President William Howard Taft (Taft, William Howard) in 1912 when Theodore Roosevelt left to form the Bull Moose Party. Promising the American people a “return to normalcy,” Harding and Coolidge achieved the greatest popular vote margin in presidential elections to that time, crushing the Democratic ticket of James Cox (Cox, James M) and Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Roosevelt, Franklin D.) by 60 to 34 percent. The electoral vote was equally one-sided: 404 to 127. Cabinet of President Calvin CoolidgeAcceding to the presidency upon Harding's unexpected death (August 2, 1923), Coolidge took the oath of office from his father, a notary public, by the light of a kerosene lamp at 2:47 AM on August 3 at the family home in Plymouth, Vermont. He inherited an administration mired in scandal. Cautiously, quietly, and skillfully, Coolidge rooted out the perpetrators and restored integrity to the executive branch. A model of personal rectitude himself, Coolidge convinced the American people that the presidency was once again in the hands of someone they could trust. The change of ambience in the White House did not miss the keen eye of Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, who said that the new White House was “as different as a New England front parlor is from a backroom in a speakeasy.” (See primary source document: The Destiny of America (Calvin Coolidge: The Destiny of America). See also Cabinet of President Calvin Coolidge.)

At the Republican convention in 1924 Coolidge was nominated virtually without opposition. Running on the slogan “Keep Cool with Coolidge,” he won a landslide victory over conservative Democrat John W. Davis (Davis, John W.) and Progressive Party candidate Robert La Follette (La Follette, Robert M), gaining about 54 percent of the popular vote to Davis's 29 percent and La Follette's nearly 17 percent; in the electoral college Coolidge received 382 votes to Davis's 136 and La Follette's 13. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address (Calvin Coolidge: Inaugural Address).)

At the Republican convention in 1924 Coolidge was nominated virtually without opposition. Running on the slogan “Keep Cool with Coolidge,” he won a landslide victory over conservative Democrat John W. Davis (Davis, John W.) and Progressive Party candidate Robert La Follette (La Follette, Robert M), gaining about 54 percent of the popular vote to Davis's 29 percent and La Follette's nearly 17 percent; in the electoral college Coolidge received 382 votes to Davis's 136 and La Follette's 13. (See primary source document: Inaugural Address (Calvin Coolidge: Inaugural Address).)Coolidge was famous for being a man of few but well-chosen words. Despite his reputation, “Silent Cal,” as he was called, had a keen sense of humour, and he could be talkative in private family settings. His wit was displayed in a characteristic exchange with a Washington, D.C., hostess, who told him, “You must talk to me, Mr. President. I made a bet today that I could get more than two words out of you.” Coolidge replied, “You lose.”

Coolidge captured the prevailing sentiment of the American people in the 1920s when he said, “The chief business of the American people is business.” The essence of the Coolidge presidency was its noninterference in and bolstering of American business and industry. Government regulatory agencies, such as the Federal Trade Commission, now were staffed by people who sought to assist business expansion rather than to police business practices. Most Americans, identifying their own prosperity with the growth of corporate profits, welcomed this reversal of progressive reforms. They generally agreed with the assessment of Oliver Wendell Holmes (Holmes, Oliver Wendell), associate justice of the Supreme Court: “While I don't expect anything very astonishing from 【Coolidge】 I don't want anything very astonishing.”

Coolidge captured the prevailing sentiment of the American people in the 1920s when he said, “The chief business of the American people is business.” The essence of the Coolidge presidency was its noninterference in and bolstering of American business and industry. Government regulatory agencies, such as the Federal Trade Commission, now were staffed by people who sought to assist business expansion rather than to police business practices. Most Americans, identifying their own prosperity with the growth of corporate profits, welcomed this reversal of progressive reforms. They generally agreed with the assessment of Oliver Wendell Holmes (Holmes, Oliver Wendell), associate justice of the Supreme Court: “While I don't expect anything very astonishing from 【Coolidge】 I don't want anything very astonishing.”Key to the conservative, pro-business focus of the Coolidge administration was Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon (Mellon, Andrew W.). A multimillionaire himself, Mellon believed strongly that reducing taxes for the rich was the best way to expand the nation's wealth. He held that, as the rich invested funds that otherwise would have been taken away in taxes, new businesses would form and older enterprises would expand and that the result would be more jobs and greater national production. Under the leadership of Coolidge and Mellon, Congress sharply reduced income taxes and estate taxes.

One form of business enterprise, however, received almost no help from the Coolidge administration: agriculture. Farmers constituted the one group of producers clearly not participating in the decade's prosperity. Twice Congress passed the McNary-Haugen bill, calling for the federal government to purchase surplus crops. Twice (1927 and 1928) Coolidge vetoed it, and the economic woes of American farmers persisted well into the following decade. Coolidge also vetoed a bill offering a bonus to veterans of World War I; Congress overrode that veto in 1924.

Reflecting its focus on internal economic growth, the Coolidge administration showed little interest in events outside the nation's borders. Coolidge adamantly opposed U.S. membership in the League of Nations (Nations, League of), though he did increase unofficial American involvement in the international organization. Ironically for such an inward-looking administration, two of its members received the Nobel Prize for Peace. In 1925, Vice President Charles G. Dawes (Dawes, Charles G.) won the prize for his program to help Germany meet its war debt obligations, and Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg (Kellogg, Frank B.) won it in 1929 for his role in negotiating the Kellogg-Briand Pact, a multinational agreement renouncing war as an instrument of national policy.

In 1928, announcing, “I do not choose to run,” Coolidge turned his back on what surely would have been another election victory and instead retired to Northampton. There he wrote a syndicated newspaper column, several magazine articles, and his autobiography (1929). And there, a little less than four years after leaving the White House, he died of a heart attack. After his death, as the country suffered through the worst economic crisis in its history, many came to view the Coolidge era as a time of inaction and complacency in the face of looming disaster. Although Coolidge's personality continued to be the butt of jokes—upon hearing that Coolidge was dead, the writer Dorothy Parker (Parker, Dorothy) quipped, “How can they tell?”—he was fondly remembered for his quiet New England virtues and for the renewed dignity and respect he brought to his office.

Coolidge was survived by first lady Grace Coolidge (Coolidge, Grace), a woman whose outgoing personality contrasted sharply with that of her tight-lipped spouse. She lived another 24 years, during which time she devoted herself to the needs of the hearing-impaired.

Additional Reading

Transcripts of about one-sixth of Coolidge's press conferences are compiled by topic in Howard H. Quint and Robert H. Ferrell (eds.), The Talkative President: The Off-the-Record Press Conferences of Calvin Coolidge (1964, reprinted 1979). Biographies include William Allen White, A Puritan in Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge (1938, reissued 1986); Claude M. Fuess, Calvin Coolidge, the Man from Vermont (1940, reissued 1976); Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President (1967, reprinted 1988); Hendrik Booraem V, The Provincial: Calvin Coolidge and His World, 1885–1895 (1994), which deals with Coolidge's youth; and Robert Sobel, Coolidge: An American Enigma (1998). Robert K. Murray, The Politics of Normalcy: Governmental Theory and Practice in the Harding-Coolidge Era (1973), discusses the Coolidge administration, though not as extensively as that of Harding; Robert H. Ferrell, The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge, emphasizes the principles behind his actions. A biographical treatment of Grace Goodhue Coolidge is found in Ishbel Ross, Grace Coolidge and Her Era: The Story of a President's Wife (1962, reprinted 1988).

- Brown, Charlotte Emerson

- Brown, Claude

- Brown, Clifford

- brown coal

- Brown, Dan

- brown dwarf

- Brown, Earle

- Browne, E Martin

- Browne, Hablot Knight

- Browne, Jackson

- Brownell, W C

- Browne, Maximilian Ulysses, Reichsgraf

- Browner, Carol M.

- Brown, Ernest William

- Browne, Robert

- Browne, Sir Thomas

- Browne, William

- Browne, William George

- Brown, Ford Madox

- Brown, George

- Brown, George Harold

- Brown, George Mackay

- Brown, Gordon

- Brown, Hallie Quinn

- Brown, Harrison