dance notation

Introduction

the recording of dance movement through the use of written symbols.

the recording of dance movement through the use of written symbols.Dance notation is to dance what musical notation is to music and what the written word is to drama. In dance, notation is the translation of four-dimensional movement (time being the fourth dimension) into signs written on two-dimensional paper. A fifth “dimension”—dynamics, or the quality, texture, and phrasing of movement—should also be considered an integral part of notation, although in most systems it is not.

Dance poses recorded through pictures date to early dynastic Egyptian wall paintings, ancient Greek vases that depict dancing figures, and iconographic examples from many other early cultures. Verbal descriptions of dances have been found in India, notably in a book dating to approximately the 2nd century BC. In Europe during the 15th to 17th centuries, many treatises on dance were written in the form of descriptions often accompanied by illustrations. However, none of these can be clearly defined as a system through which actual dance movements (as opposed to positions) could be captured and subsequently faithfully reconstructed.

The Renaissance (c. early 15th–early 17th century)

The first device to be considered a true notation system was found in Cervera, Catalonia (now part of Spain): two manuscript pages, dated from the 15th century, revealed the first use of signs to represent the letter abbreviations used in Renaissance Italy, France, and Spain to record the popular basse danses (basse danse) (“low dances”). These were letter abbreviations for the five well-known steps: R for révérence; s for simple; d for double; b for branle; and r for reprise. Dances were composed of a sequence of these steps in different arrangements.

In his book Orchesographie (1588), the Frenchman Thoinot Arbeau (Arbeau, Thoinot) provided valuable descriptions of the dances of that period, placing the names of the dancer's movements next to the vertically arranged music. His system, however, cannot be called a notation system as such, because no symbols were used.

The Baroque period (c. 17th–18th century)

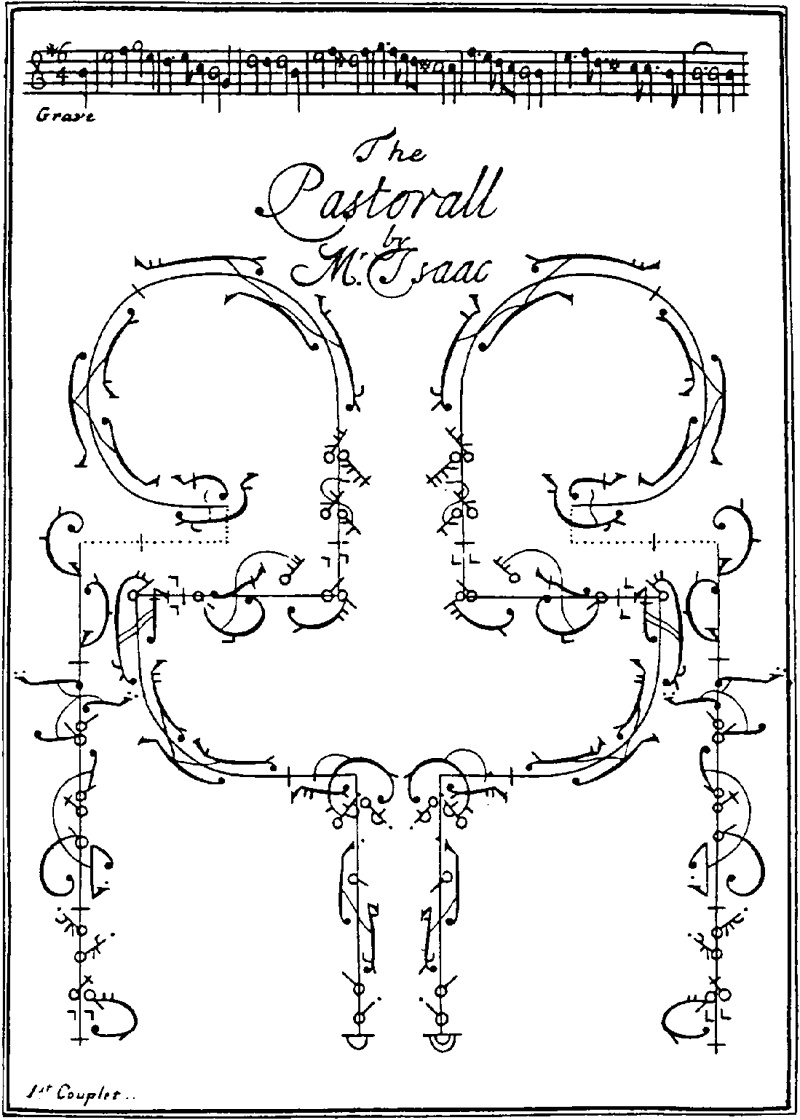

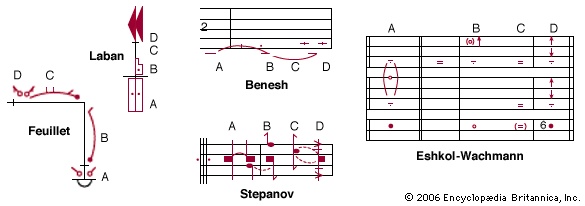

At the French court of Louis XIV, patterns traced on the floor were an important part of formal dances; drawings of these pathways, with signs added to indicate the steps used, were the basis of the first important, widely used dance notation system. Originated by the ballet teacher Pierre Beauchamp (Beauchamp, Pierre), it was first published by his student Raoul-Auger Feuillet (Feuillet, Raoul-Auger) in 1700 as Chorégraphie; ou, l'art de décrire la danse (“Choreography; or, The Art of Describing the Dance”). The system spread rapidly throughout Europe, with English, German, and Spanish versions soon appearing. Well suited to the dance of that era, which featured intricate footwork, this notation became so popular at court and among the educated classes that, for a while, books of collected dances were published annually. Indications for the appropriate arm gestures were later developed to accompany the intricacies of the footwork. However, at the watershed of the French Revolution, when dance for the educated classes at the royal courts declined, the Feuillet system—which was unsuited to theatre dance with its greater range of movement—fell into disuse.

At the French court of Louis XIV, patterns traced on the floor were an important part of formal dances; drawings of these pathways, with signs added to indicate the steps used, were the basis of the first important, widely used dance notation system. Originated by the ballet teacher Pierre Beauchamp (Beauchamp, Pierre), it was first published by his student Raoul-Auger Feuillet (Feuillet, Raoul-Auger) in 1700 as Chorégraphie; ou, l'art de décrire la danse (“Choreography; or, The Art of Describing the Dance”). The system spread rapidly throughout Europe, with English, German, and Spanish versions soon appearing. Well suited to the dance of that era, which featured intricate footwork, this notation became so popular at court and among the educated classes that, for a while, books of collected dances were published annually. Indications for the appropriate arm gestures were later developed to accompany the intricacies of the footwork. However, at the watershed of the French Revolution, when dance for the educated classes at the royal courts declined, the Feuillet system—which was unsuited to theatre dance with its greater range of movement—fell into disuse.The Romantic period (late 18th–late 19th century)

In the mid-19th century two important systems were published, both based on the idea of “stick figure” representation. That of the renowned French dancer and choreographer Arthur Saint-Léon (Saint-Léon, Arthur), illustrated in his book Sténochorégraphie, was published in 1852. It combined slightly abstracted figure drawings with musical note indications for specific timing—not a surprising addition considering Saint-Léon's musical background (he had been a child prodigy on the violin). His inclusion in his book of the pas de six from his ballet La Vivandière provided a valuable example of a Romantic ballet, and it has been studied and performed into the 21st century. The second of the two major mid-19th-century notation systems was that of the German dance teacher Friedrich Albert Zorn, whose book Grammatik der Tanzkunst (1887; Grammar of the Art of Dancing) employed a more directly pictorial stick figure, placed under the accompanying music to indicate timing. A highly respected dancing master, Zorn focused on detailed descriptions of the exercises and steps required in dance training. He included a selection of dances, notably the cachucha solo made famous in 1836 by the Austrian ballerina Fanny Elssler (Elssler, Fanny).

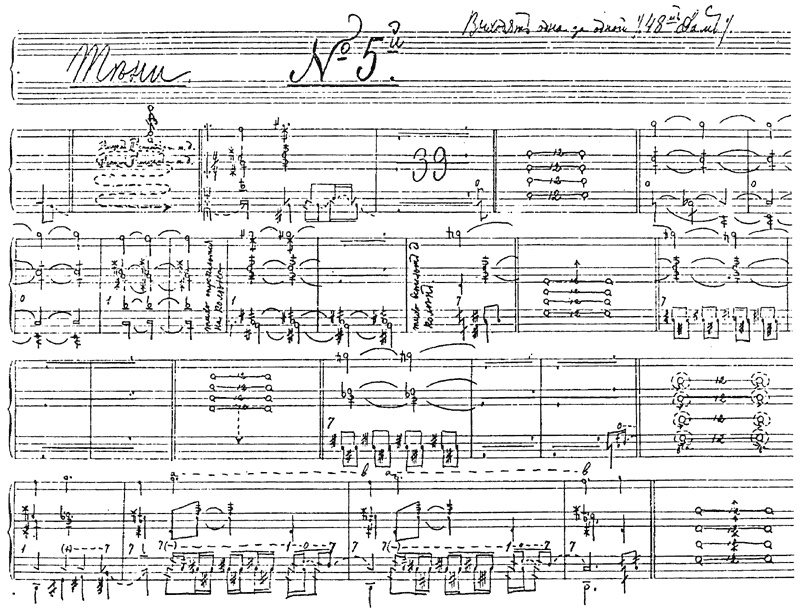

The close affinity between music and dance made inevitable the idea of using musical notes to record movement. The first such system was developed by Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov, a dancer of the Mariinsky Ballet in St. Petersburg; it was published in Paris with the title Alphabet des mouvements du corps humain (1892; Alphabet of Movements of the Human Body). Stepanov's method was based on an anatomical analysis of movement and thus was applicable to the recording of any type of movement. Stepanov's method was adopted by the Mariinsky, where it was used to record the repertory. Of the scores notated during that period, many were incomplete, rapidly written notes intended as memory aids. The dancer and choreographer Léonide Massine (Massine, Léonide) learned Stepanov notation as a student at the Imperial School of Ballet and made use of it in developing his own choreographic theories. His Massine on Choreography was published in 1976.

The close affinity between music and dance made inevitable the idea of using musical notes to record movement. The first such system was developed by Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov, a dancer of the Mariinsky Ballet in St. Petersburg; it was published in Paris with the title Alphabet des mouvements du corps humain (1892; Alphabet of Movements of the Human Body). Stepanov's method was based on an anatomical analysis of movement and thus was applicable to the recording of any type of movement. Stepanov's method was adopted by the Mariinsky, where it was used to record the repertory. Of the scores notated during that period, many were incomplete, rapidly written notes intended as memory aids. The dancer and choreographer Léonide Massine (Massine, Léonide) learned Stepanov notation as a student at the Imperial School of Ballet and made use of it in developing his own choreographic theories. His Massine on Choreography was published in 1976.Twentieth-century developments

Another student who learned Stepanov notation at the Imperial School was the legendary Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky (Nijinsky, Vaslav), whose interest in it led to his own modification of the system, one that improved significantly on Stepanov's ideas, especially in the indication of directions and levels. During a period of inactivity when he was separated from the Ballets Russes, Nijinsky worked on his notation ideas and recorded every movement of his first ballet, L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912; Afternoon of a Faun). When in 1988 the code to his system was broken, this ballet could be revived in its authentic version—that notated by Nijinsky himself.

The 20th century was marked by the advent of abstract symbol systems, notably those of Margaret Morris and Rudolf Laban (Laban, Rudolf). Morris, a British dancer, teacher, and choreographer, was also a movement therapist, which led to her anatomical approach to recording movement. She outlined her system in The Notation of Movement (1928); in addition to direction symbols, she provided separate signs for each movement of each part of the body. This was not an advantage in comparison with “alphabet” systems, in which the same basic type of movement is written with the same symbol for each part of the body.

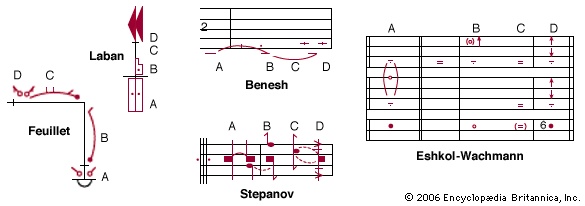

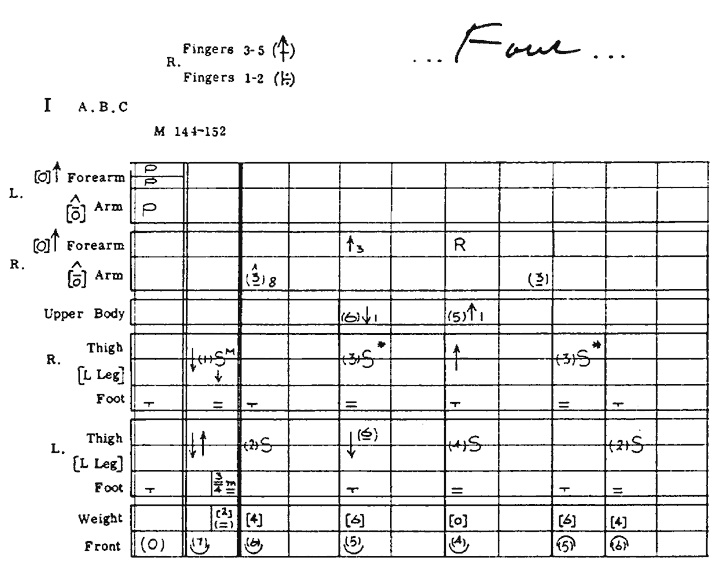

Schrifttanz (1928; “Written Dance”), by the Hungarian-born dance theorist Rudolf Laban, provided the basis for the notation system that bears his name: labanotation (also called Kinetography Laban). Laban had an eclectic interest in movement but found himself architecturally fascinated by its spatial aspects. Thus, his system initially depicted movement from a spatial perspective; an anatomical description was added later by others. It is an “alphabet” system in that each movement is “spelled out” according to the sequence of its basic components. A vertical three-line staff represents the body, the centre line dividing right and left. The shape and shading of the movement symbols indicate direction and level; their length indicates timing (duration); and their placement in the appropriate column on the staff indicates the part of the body that is moving. A particular strength of labanotation is its ability to show precise gradations in the timing of movements. The system became widely used because it is applicable to all forms of movement. For decades labanotation was refined by research practitioners working in a variety of different movement disciplines, not only ballet and contemporary choreographies but dance of different styles and cultures as well as gymnastics and other sports, remedial exercises, and even zoological studies.

Schrifttanz (1928; “Written Dance”), by the Hungarian-born dance theorist Rudolf Laban, provided the basis for the notation system that bears his name: labanotation (also called Kinetography Laban). Laban had an eclectic interest in movement but found himself architecturally fascinated by its spatial aspects. Thus, his system initially depicted movement from a spatial perspective; an anatomical description was added later by others. It is an “alphabet” system in that each movement is “spelled out” according to the sequence of its basic components. A vertical three-line staff represents the body, the centre line dividing right and left. The shape and shading of the movement symbols indicate direction and level; their length indicates timing (duration); and their placement in the appropriate column on the staff indicates the part of the body that is moving. A particular strength of labanotation is its ability to show precise gradations in the timing of movements. The system became widely used because it is applicable to all forms of movement. For decades labanotation was refined by research practitioners working in a variety of different movement disciplines, not only ballet and contemporary choreographies but dance of different styles and cultures as well as gymnastics and other sports, remedial exercises, and even zoological studies.A number of other notation systems were invented in the 20th century. Pierre Conté, a French musician, wrote Écriture de la danse théatrale et de la danse en général (1931; “Writing of Theatrical Dance and Dance in General”); his system combined musical notes with simple signs placed on an expanded music staff. In Choroscript (written in 1945 and unpublished), the American musician, dance teacher, and choreographer Alwin Nikolais (Nikolais, Alwin) indicated movement with modified musical notation symbols. Nikolais's movement analysis was based on labanotation, and he used a Laban-style vertical staff but in two parts, with torso and head indications placed separately on the right. Kineseography (1955), created by the dancer and choreographer Eugene Loring with D.J. Canna, incorporated an unusual movement analysis. This system used a vertical staff and simple signs to record four categories of movement: Emotion, Direction, Degree, and Special. It was used to record Loring's signature ballet, Billy the Kid (1938).

The system developed by the Israeli dance theorist Noa Eshkol and the architect Abraham Wachmann was first published in English as Movement Notation in 1958. It took an anatomical and mathematical view of movement and initially had the aim of exploring the abstract shapes and designs of movement rather than recording existing dance patterns, which had been the primary goal of all previous systems. Numbers and a small selection of symbols are used to represent each possible physical motion. The full horizontal staff provides a space for each body segment. Eshkol's original aim was to create a method of recording her own choreography; however, the Movement Notation Society in Israel (the centre for this system) subsequently published books on folk dance, ballet, and other art forms and also illustrated the uses of the system in recording the movements of animals.

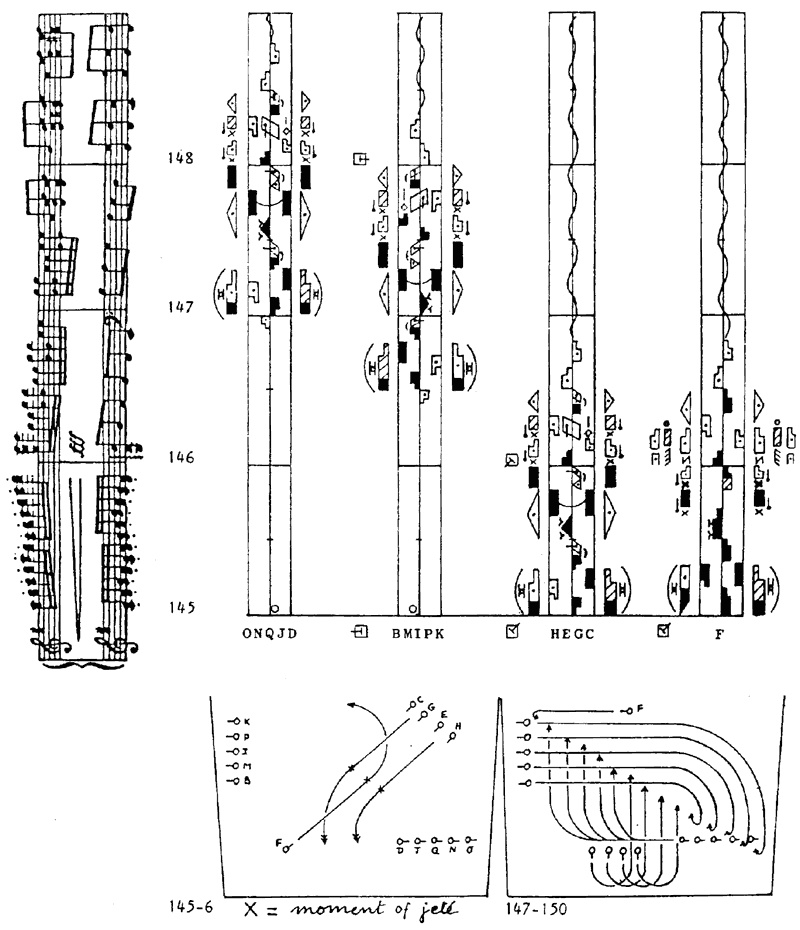

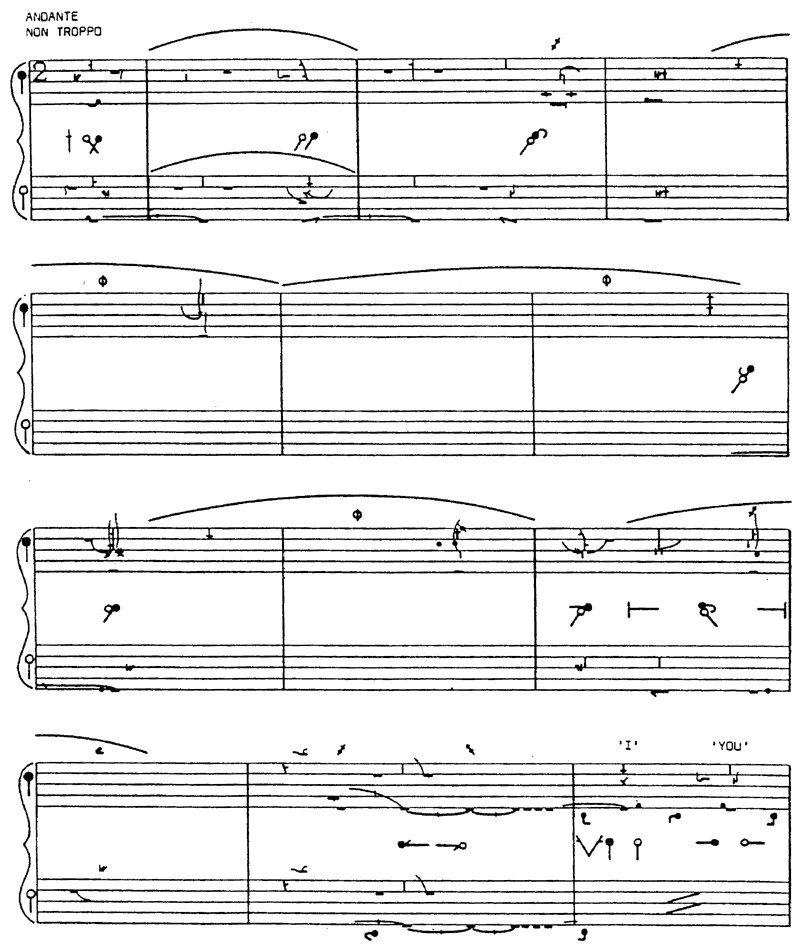

The system developed by the Israeli dance theorist Noa Eshkol and the architect Abraham Wachmann was first published in English as Movement Notation in 1958. It took an anatomical and mathematical view of movement and initially had the aim of exploring the abstract shapes and designs of movement rather than recording existing dance patterns, which had been the primary goal of all previous systems. Numbers and a small selection of symbols are used to represent each possible physical motion. The full horizontal staff provides a space for each body segment. Eshkol's original aim was to create a method of recording her own choreography; however, the Movement Notation Society in Israel (the centre for this system) subsequently published books on folk dance, ballet, and other art forms and also illustrated the uses of the system in recording the movements of animals. Despite the introduction of abstract symbol systems, notation methods making use of stick figures continued to appear during the 20th century. The most successful of these was a visual representation system devised in the 1950s by the English artist Rudolf Benesh and his wife, Joan Benesh, a dancer with the Sadler's Wells Ballet (now the Royal Ballet). A matrix on a five-line horizontal staff represents the dancer from head to foot, seen from the back. Positions and movement lines are plotted on this matrix. Timing indications are placed above the staff. More complex movements that cannot be indicated visually on the staff are written with additional signs and numbers above the staff. Initially developed as a ballet shorthand, it has proved very useful in recording the repertoires of ballet companies. The Benesh Institute was established in London in 1962. Following the example set in the 1960s by the Royal Ballet, many companies have hired trained Benesh notators. Computer programs for writing Benesh scores have been developed, and a centre for training notators and producing publications was established in the 1990s at the Centre National de la Danse in Paris.

Despite the introduction of abstract symbol systems, notation methods making use of stick figures continued to appear during the 20th century. The most successful of these was a visual representation system devised in the 1950s by the English artist Rudolf Benesh and his wife, Joan Benesh, a dancer with the Sadler's Wells Ballet (now the Royal Ballet). A matrix on a five-line horizontal staff represents the dancer from head to foot, seen from the back. Positions and movement lines are plotted on this matrix. Timing indications are placed above the staff. More complex movements that cannot be indicated visually on the staff are written with additional signs and numbers above the staff. Initially developed as a ballet shorthand, it has proved very useful in recording the repertoires of ballet companies. The Benesh Institute was established in London in 1962. Following the example set in the 1960s by the Royal Ballet, many companies have hired trained Benesh notators. Computer programs for writing Benesh scores have been developed, and a centre for training notators and producing publications was established in the 1990s at the Centre National de la Danse in Paris. In the United States a labanotation score was first accepted for copyright protection in 1952. This event was a major breakthrough that afforded dance a protection it had not experienced until then. Subsequently, many notated scores were submitted for copyright registration.

In the United States a labanotation score was first accepted for copyright protection in 1952. This event was a major breakthrough that afforded dance a protection it had not experienced until then. Subsequently, many notated scores were submitted for copyright registration.Notation systems were developed in other countries, such as Russia and Romania, where they were used to record traditional folk dances. One of the more significant of these was Romanotation, first published by the ethnochoreologist Vera Proca-Ciortea in 1956. A decade later the dance teacher and choreographer Theodor Vasilescu developed a different system to describe Romanian folk dances, with a view toward teaching them.

Efforts to document Korean dance movements include the method developed in North Korea about 1970 by the Korean choreographer U Chang Sop. His book, published in English as Chamo System of Dance Notation (1988), uses pictorially based symbols and additional abstract signs.

In India during the 1970s, the classical-dance performer Gopal Venu devised a notation system with the aim of providing a shorthand for the many mudras (hand positions) needed in kathakali (kathākali) dance-drama. These are combined with pictographs of body positions.

Manuscripts from the Han dynasty in China record dance through pictures with a few symbols, none of which has been clearly deciphered. The first true notation system in China was Coordination Method Dance Notation (Eng. trans. 1987), created by Wu Ji Mei and her husband, Gao Chun Lin, in the early 1980s. Based on a logical movement analysis and placed under the (Western) music staff to show timing, it uses letters of the alphabet, numbers, and a few abstract signs and thus is typeable on a computer keyboard. It has been applied to dance forms, movement in sports, and physical education.

Conclusion

Although good, workable systems have been around for centuries, the use of dance notation has never been an integral part of dance study and practice, as musical notation is in the study of music. Writing a dance score inevitably takes time, as does writing a book or a symphony; the time spent learning to read and write notation was often seen as wasted. Until the development in the 1960s of the simple Motif Notation (related to labanotation) and its application in the Language of Dance teaching method, in which the basic movement “building blocks” are explored, notation was not included in a child's introduction to movement; dance was still taught solely by imitation. The study of labanotation includes an investigation into movement that not only enriches a dancer's understanding of movement but also provides dance students with access to the scores of significant works of the past.

The advent of film and particularly in the 1970s of video recording overshadowed notation. Video has immediate appeal to dancers because it requires no lengthy study. Through experience, however, members of the dance world have come to recognize its limitations. The image is often not clear, and costumes or other dancers often block the view. A video is a record of a particular performance in which the dancers may have made mistakes (which is frequently the case); the viewer is unable to recognize the difference between the dance performance and the dance itself. Learning from video too often results in the personal mannerisms or mistakes of one dancer being picked up and exaggerated by another, which thus distorts the choreography. In contrast, the notated score is a record of the work itself in the same way that a musical score represents the work, not an individual's performance of that work. In a score all aspects of choreographic detail—use of stage space, the relationship of performers to each other and to the music, and the choreographer's development of movement themes—can be easily studied.

Although its use in the dance field has spread more slowly than many dance historians anticipated, notation remains an essential tool. In addition to accurately recording a working choreographer's movement concepts, it uniquely enables the faithful preservation of past works—a major concern in the dance world. In music, scores from centuries past have preserved classic works, which modern composers may wish to modify, rearrange, or parody without loss of the originals. In dance, reliance on memory has resulted in an accumulative distortion of the originals. Without notation, unintentional changes soon become the known version, and the viewing public has no idea of the loss of authenticity.

Additional Reading

A history of dance notation from the Renaissance to the present is found in Ann Hutchinson Guest, Dance Notation: The Process of Recording Movement on Paper (1984), and her Choreo-graphics (1989) is a detailed comparison of 14 different dance notation systems. Feuillet notation is explained and illustrated in Wendy Hilton, Dance of Court & Theatre (1981). The basic textbook on the Benesh system is Rudolf Benesh and Joan Benesh, An Introduction to Benesh Movement-Notation: Dance, rev. and extended ed. (1969). Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov, Alphabet of Movements of the Human Body, trans. from French (1969), describes the Stepanov notation system. Ann Hutchinson Guest, Labanotation, 4th ed. (2005), is the basic textbook on that system. The original source on Eshkol-Wachmann notation is Noa Eshkol and Abraham Wachmann, Movement Notation (1958).

- Enceladus

- Encephalartos

- encephalitis

- enchanter's nightshade

- Enchi Fumiko

- enchondroma

- Enciclopedia italiana di scienze, lettere ed arti

- Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europeoamericana

- Encina, Juan del

- Encke, Johann Franz

- Enckell, Rabbe

- Encke's Comet

- enclosed rhyme

- enclosure

- encomienda

- encomium

- Encratite

- encyclical

- encyclopaedia

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Encyclopedia Americana, The

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Encyclopédie

- Endamoeba

- endangered species