Tai languages

Introduction

closely related family of languages, of which the Thai (Thai language) language of Thailand is the most important member. Because the word Thai has been designated as the official name of the language of Thailand, it would be confusing to use it for the various other languages of the family as well. Tai is therefore used to refer to the entire group.

The distribution and classification of Tai languages

Spoken in Thailand, Laos, Myanmar (Burma), Assam in northeastern India, northern Vietnam, and the southwestern part of China, the Tai languages together form an important group of languages in Southeast Asia. In some countries they are known by different tribal names or by designations used by other peoples. For example, there is Shan in Myanmar; Dai in Yunnan, China (includes languages known outside China as Nüa and Lü); Zhuang in Guangxi, China; Buyei in Guizhou, China; Tay, Nung, White Tai, Black Tai, Red Tai, and others in northern Vietnam; and Khün, Lü, and others in Thailand and Laos. Designations vary over time as well: older names include Pai-i (Dai); Chuang-chia (Zhuang); Chung-chia, Dioi, Jui, and Yai (Buyei); and Tho, which is still sometimes used for the language or languages now known in Vietnam as Tay. Ahom, an extinct language once spoken in Assam (India), has a considerable amount of literature. The Tai languages are divided into three linguistic groups—the Southwestern, the Central, and the Northern. Thai and Lao (Lao language), the official languages of Thailand and Laos, respectively, are the best known of the languages.

Spoken in Thailand, Laos, Myanmar (Burma), Assam in northeastern India, northern Vietnam, and the southwestern part of China, the Tai languages together form an important group of languages in Southeast Asia. In some countries they are known by different tribal names or by designations used by other peoples. For example, there is Shan in Myanmar; Dai in Yunnan, China (includes languages known outside China as Nüa and Lü); Zhuang in Guangxi, China; Buyei in Guizhou, China; Tay, Nung, White Tai, Black Tai, Red Tai, and others in northern Vietnam; and Khün, Lü, and others in Thailand and Laos. Designations vary over time as well: older names include Pai-i (Dai); Chuang-chia (Zhuang); Chung-chia, Dioi, Jui, and Yai (Buyei); and Tho, which is still sometimes used for the language or languages now known in Vietnam as Tay. Ahom, an extinct language once spoken in Assam (India), has a considerable amount of literature. The Tai languages are divided into three linguistic groups—the Southwestern, the Central, and the Northern. Thai and Lao (Lao language), the official languages of Thailand and Laos, respectively, are the best known of the languages.The number of Tai speakers is estimated at 80 million. Of these, about 55 million are in Thailand, some 18 million in China, and about 7 million in Laos, northern Vietnam, and Myanmar. There are tremendous variations between several estimates, and these figures may serve as only rough indications of the Tai populations.

The relationship of Tai languages to other language families

Tai as a group is related to a number of other languages and groups of southern China, the most populous being the Kam-Sui languages, spoken mostly in Guizhou, China; and the Li, or Hlai, languages of Hainan. The entire language family containing Tai and all its relatives is called either Tai-Kadai or simply Kadai. The former assumption that Tai and its relatives belonged to the Sino-Tibetan (Sino-Tibetan languages) family is now not widely accepted. The similarity between the Tai and Chinese phonological systems (especially tone) is no longer taken as criterial, and, although many lexical items are also shared with Chinese, many more are not, and the latter include much of the most basic vocabulary. A competing proposal links Tai and its relatives with Austronesian (Austronesian languages), but this connection has not yet been established to the satisfaction of most scholars.

Classification within the family

Criteria for classification

Classifications have been made according to the geographic location of the Tai speakers, social, political, and cultural criteria, and literacy versus nonliteracy. The classification used for this article is based on linguistic relationships proposed in 1959–60; the criteria for it are lexical (involving similarities in vocabulary) and phonological (involving similarities in sounds and systems of sounds). According to these features the Tai languages are divided into the three groups mentioned above (see map). Languages of the Southwestern group are spoken in Thailand, Laos, northern Vietnam, Myanmar, and Yunnan, China; they include Thai, Lao, Shan, Khün, Lü, White Tai, Black Tai, and others. The Southwestern division, which is geographically the most widespread group, consists of two-thirds of the Tai-speaking population and represents an expansion that has occurred in comparatively recent periods. To the Central group belong the Tay dialects that are spoken in northern Vietnam and the various dialects spoken in Guangxi, such as Longzhou. The Buyei dialects in Guizhou and the Zhuang dialects in Guangxi belong to the Northern group. Some of the Northern dialects are also spoken in Yunnan and Vietnam, and one, called Saek, is spoken as far south as Laos and Thailand.

Differences in vocabulary (comparative linguistics)

The fairly large number of vocabulary items that are shared by languages of these three groups suggests their genetic relationship. In some instances, however, there are items that are shared by only two of the groups and are not found in the other. For instance, the word for ‘sky' is shared by the Southwestern dialects (Thai fáa) and the Central dialects (Longzhou faa), but another word is used in the Northern dialects (Buyei mɯn). Similarly, the word for ‘beard' is shared by the Central group (Longzhou mum) and the Northern group (Buyei mum) but is replaced by another word in the Southwestern group (Thai nùat). In another instance the term for ‘knife' is shared by the Southwestern (Thai mîit) and the Northern groups (Buyei mit) but not by the Central dialects, which have various words such as Leibing taau and Ning Ming pjaa (Longzhou has both pja and taau). There are also vocabulary items that are found only in one of the three groups. The evidence seems to indicate that there are three groups of dialects (dialect) in the Tai family.

Differences in phonology

Different phonological features may be reconstructed for the ancestral form of some words according to the dialect group. For instance, the Southwestern forms for the verb ‘to be' (Thai pen) are derived from a protoform *pɛn (with the vowel pronounced as in English egg), whereas the Central dialect forms (Longzhou pin) and the Northern forms (Buyei pan) come from a protoform *bɛn. (A protoform is the presumed or reconstructed ancestral form of a word; an asterisk 【*】 indicates an unattested, reconstructed form.) Similarly, the Southwestern and the Central forms for the classifier for animals (Thai tua, Longzhou tuu) are derived from a protoform *tua, whereas the Northern forms (Buyei tuu) are attributed to a protoform *dua. (A classifier is a term that indicates the group to which a noun belongs 【for example, ‘animate object'】 or designates countable objects or measurable quantities, such as ‘yards 【of cloth】' and ‘head 【of cattle】'.) Such words as the forms for ‘to be' and the classifier for animals are good indications of dialect boundaries.

In phonological development, the Northern dialects differ from the rest in not maintaining the distinction between aspirated (aspirate) and unaspirated voiceless stops. That is, the dialects have lost the feature of aspiration, which sounds like a puff of breath accompanying a consonant. Aspiration may, however, be reintroduced in some dialects by later borrowing or secondary developments. The Central dialects differ from the other groups in the treatment of certain Proto-Tai consonant clusters, such as *tr- and *thr-. Although they have changed from the protoforms, these are usually kept distinct in the other groups—e.g., in Thai as taa (‘eye') and haaŋ (‘tail'), in Buyei as taa and lŋ. In the Central dialects, however, they have merged into a single sound—e.g., Tay thaa and thaaŋ, Longzhou haa and haaŋ.

Linguistic characteristics

Phonological characteristics

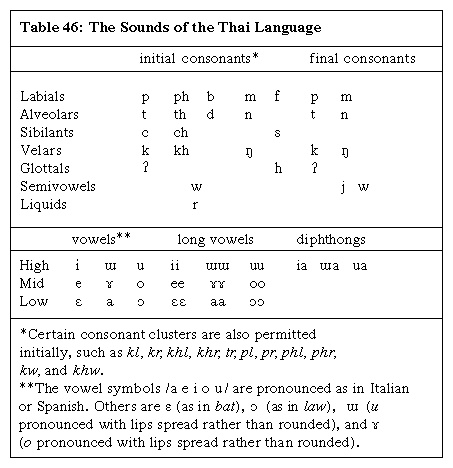

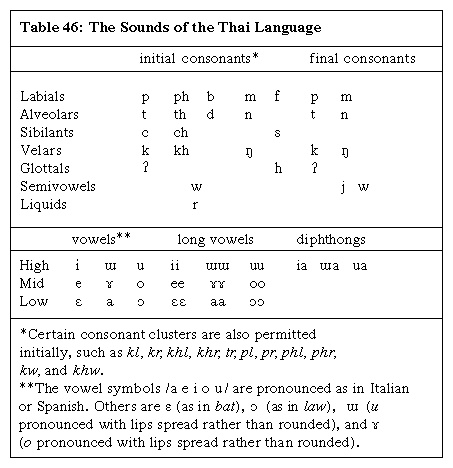

The sound system of the Tai languages may best be described in terms of its syllabic structure. Each syllable consists of an initial consonant or consonant cluster followed by a vowel or vowel cluster (long vowel or diphthong), which may be further followed by a final consonant, usually a nasal sound or an unreleased stop. (An unreleased stop is a consonant in which there is complete stoppage of the airstream from the lungs and in which the tongue or the lips maintain the position of the consonant without opening the stoppage.) In addition, each syllable has a tone (i.e., the syllable must be pronounced with a certain pitch level and contour in all contexts. This can be illustrated (seetable-->

The sound system of the Tai languages may best be described in terms of its syllabic structure. Each syllable consists of an initial consonant or consonant cluster followed by a vowel or vowel cluster (long vowel or diphthong), which may be further followed by a final consonant, usually a nasal sound or an unreleased stop. (An unreleased stop is a consonant in which there is complete stoppage of the airstream from the lungs and in which the tongue or the lips maintain the position of the consonant without opening the stoppage.) In addition, each syllable has a tone (i.e., the syllable must be pronounced with a certain pitch level and contour in all contexts. This can be illustrated (seetable--> ) by the five tones of Siamese, or Standard Thai, a national standard based on the language spoken in the Bangkok area.

) by the five tones of Siamese, or Standard Thai, a national standard based on the language spoken in the Bangkok area.The Thai tones are as follows: level (using no diacritic), low (using a grave accent), falling (using a circumflex), high (using an acute accent), and rising (using a wedge, or haček); for example, maa (with no diacritic) ‘to come,' màak (with a grave accent) ‘areca nut,' mâak (with a circumflex) ‘much,' máa (with an acute accent) ‘horse,' and mǎa (with a wedge) ‘dog' are differentiated by various tones.

Grammatical characteristics

The statements about morphology and syntax refer particularly to the standard language of Thailand, though they are applicable in general to all the Tai languages.

morphology

Words or morphemes (word elements) are, for the most part, monosyllabic, but there are also many polysyllabic words, mainly compounds and loanwords from the Indic languages Sanskrit (Sanskrit language) and Pali (Pāli language) and from Khmer (Khmer language), an Austroasiatic language spoken mainly in Cambodia. There are no inflections in Tai comparable to -ed in English ‘walked' or -s in ‘dogs.' The chief Tai method of forming new words is compounding—e.g., nâa-taa ‘countenance' (literally, ‘face-eye'), kèp-kìaw ‘to harvest' (literally, ‘gather-cut with a sickle'). Reduplication, the repetition of a word or part of it, is also quite common—e.g., díi-dii ‘very good' from dii ‘good.' Partial reduplication is also found, such as sanùk-sanǎan ‘to enjoy oneself' from sanùk ‘to have fun.' Some Tai languages have developed prefixes by abbreviating forms that were once full words; prefixes and infixes are also common in the Indic and Khmer loans into the more southerly Tai languages—e.g., pra-thêet ‘country' (from Sanskrit pradeśa) and d-amn-ɤɤn ‘to proceed,' derived from dɤɤn ‘walk' (from Khmer damnaɤ ‘gait, bearing' and dae ‘walk,' respectively). There also developed some native prefixes that are abbreviated forms of what once were full words. For example, ma-, a prefix used in many names of fruits, such as ma-phráaw ‘coconut,' ma-mûaŋ ‘mango,' is derived from màak ‘areca nut' (originally ‘fruit'). Similarly, in the word sa-dɯˇɯ ‘navel,' sa- is the reduced form of sǎaj ‘line, string,' which refers to the umbilical cord. Old processes of derivation involved using the alternation of consonants or tone or both, such as níi ‘this' and nîi ‘here,' nɔɔj ‘small, little' and nɔɔj ‘a little bit,' khiaw ‘sickle' and kìaw ‘to cut with a sickle.' Such processes are, however, no longer active.

syntax

Word order is generally subject–verb–object (SVO), and modifiers such as adjectives and possessive nouns follow the item they modify. The verb plus object (verb phrase) functions as predicate. Words translatable as English adjectives also commonly function as predicate and can be negated; hence, they are considered a type of verb. Nouns too may also function as predicate in certain contexts; an example is wan-níi wan-sǎḳ ‘today (is) Friday.' A noun phrase consists of a noun, which may be followed by its modifiers (another noun, an adjective, or a verb phrase), which, in turn, are followed by a numeral with a classifier and, finally, by a demonstrative. For example, tûu ‘cabinet' and náŋsɯˇɯ ‘book' become tûu-náŋsɯˇɯ ‘bookcase'; tûu-kèp náŋsɯˇɯ is also ‘bookcase' (‘cabinet-keep-book'); tûu-yen is ‘icebox' (‘cabinet-cool'); and tûu-kèp-náŋsɯˇɯ sɔɔŋ-baj níi is ‘these two bookcases' (‘cabinet-keep-book two-classifier these'). Numerals and demonstratives cannot be used directly with nouns but must be used with a classifier, a word similar in function to English head in the phrase fifty head of cattle.

A verb phrase may consist of an adjective or of a verb, often followed by its object or its complements or both. A common type of complement denotes the direction of action by using such words as paj ‘to go,' maa ‘to come,' khɯˆn ‘to ascend,' loŋ ‘to descend,' and so on. Examples are ʔaw náŋsɯˇɯ paj ‘Take the book away!'; ʔaw náŋsɯˇɯ maa ‘Bring the book (here)!'; aw náŋsɯˇɯ khɯˆn maa ‘Bring the book up!'; and aw náŋsɯˇɯ loŋ paj ‘Take the book down!'. Short words, known as particles and occurring mostly at the end of the sentence, indicate meanings such as completion or continuation of action, question or command, emphasis or uncertainty, and degree of politeness or intimacy. For example, kháw maa lεεw ‘He has come'; kháw maa máj ‘Is he coming?'; khun maa máj khráp ‘Are you coming?' (man speaking, polite); khun maa máj khá ‘Are you coming?' (woman speaking, polite).

Vocabulary

The various Tai languages have been in contact with many different languages spoken in the same area of Southeast Asia, and it is inevitable that words from different sources have been adopted by them. There is a basic core of vocabulary that is shared by most of the Tai languages and may be considered as the native vocabulary of the protolanguage. Nevertheless, items in this list may be found to resemble forms in other languages, such as Chinese or Indonesian, and they have given rise to different interpretations of the relationship of the Tai languages to other linguistic families. Loanwords in later periods from the Khmer and Indic languages (Sanskrit and Pali) are particularly common in Thai and Lao (Lao language), and loans from Chinese are abundant in the Central and the Northern dialects.

Writing

Two different types of writing have been used among the Tai languages. One, ultimately derived from Chinese (Chinese languages), is used by the Central and the Northern dialects; the other comes from Indic sources and is used in many languages of the Southwestern group. The Chinese-based system, which is employed chiefly to write songs, consists of Chinese characters, some modified since the 18th century, but it may have been in use much earlier. The other type of writing system, first attested in the 13th century, derives from the Southern Indic type of script. The earliest known example of the Indic-based writing system is the inscription of Ramkhamhaeng in northern Thailand (Thai language) from AD 1293. There are many forms of this type of script, used by a number of languages in the Southwestern group as well as by neighbouring languages, such as Mon, Khmer, and Burmese.

The Modern Thai alphabet (see table-->

The Modern Thai alphabet (see table--> ) is a modified form of the original writing. It preserves the old distinction of voiced (low), voiceless aspirate (high), and voiceless unaspirate/glottalized (middle), a distinction now largely lost but one that nevertheless leaves its effects on the tone. This system also provides an unambiguous method for indicating the vowels and tones. Similar types of writing are used in Lao, Lü, White Tai, Black Tai, and other languages. Some scripts, such as those used by Shan, Ahom, and Nüa (Dehong Dai of Yunnan, China), have in their traditional forms insufficient vowel signs and few or no tone markers. The Shan and Nüa scripts now also exist in reformed and augmented versions that distinguish all vowels and tones.

) is a modified form of the original writing. It preserves the old distinction of voiced (low), voiceless aspirate (high), and voiceless unaspirate/glottalized (middle), a distinction now largely lost but one that nevertheless leaves its effects on the tone. This system also provides an unambiguous method for indicating the vowels and tones. Similar types of writing are used in Lao, Lü, White Tai, Black Tai, and other languages. Some scripts, such as those used by Shan, Ahom, and Nüa (Dehong Dai of Yunnan, China), have in their traditional forms insufficient vowel signs and few or no tone markers. The Shan and Nüa scripts now also exist in reformed and augmented versions that distinguish all vowels and tones.Additional Reading

Studies of the Tai languages include Mary R. Haas, Thai-English Student's Dictionary (1964), a concise dictionary arranged according to the order of the Thai alphabet with a brief description of the phonological and grammatical system; Mary R. Haas and Heng R. Subhanka, Spoken Thai, 2 vol. (1945, reissued 1978), a textbook; George Bradley McFarland, Thai-English Dictionary (1941, reprinted 1974), with more extensive lexical coverage but with a nonstandard transcription of Thai pronunciation; Fang Kuei Li (Fang-kuei Li), A Handbook of Comparative Tai (1977), which lists more than 1,000 sets of cognate words in three Tai languages and gives reconstructions of the initial consonants, vowels, and tones of the ancestral Proto-Tai language, and “The Tai and the Kam-Sui Languages,” Lingua, 14:148–179 (1965), a discussion of the relationship of these two language groups; Richard B. Noss, Thai Reference Grammar (1964), a detailed descriptive and structural analysis; Paul K. Benedict, Austro-Thai Language and Culture, with a Glossary of Roots (1975), an attempt to show a relationship between the Tai(-Kadai) languages and the Austronesian languages; and Tatsuo Hoshino and Russell Marcus, Lao for Beginners: An Introduction to the Spoken and Written Language of Laos (1981). Lexical resources on other Tai languages such as Yay, Lue, Saek, and regional dialects include the various volumes in the Michigan Papers on South and Southeast Asia series by William J. Gedney, ed. by Thomas John Hudak, each of which contains an extensive glossary and transcriptions of either texts or example sentences.

- Cruces

- crucible

- crucible furnace

- crucible process

- crucifixion

- crucifixion thorn

- Crucé, Émeric

- Cruden Bay

- crude oil

- Crudup, Arthur

- Cruelty, Theatre of

- Cruikshank, George

- cruise missile

- cruiser

- Cruise, Tom

- Crumb, George

- crumhorn

- Crumley, James

- Crummell, Alexander

- Crusades

- Crusca Academy

- cruse lamp

- crush injury

- crust

- crustacean