Tanzania

Introduction

officially United Republic of Tanzania, Swahili Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania

Tanzania, flag of East African country situated just south of the Equator. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean on the east and eight other nations: Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo (Kinshasa), Zambia, Malaŵi, and Mozambique. Tanzania was formed as a sovereign state in 1964 through the union of the theretofore separate states of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Mainland Tanganyika constitutes more than 99 percent of the combined territories' total area. Mafia Island is administered from the mainland, while Zanzibar and Pemba islands (Pemba Island) have a separate government administration. Dodoma, since 1974 the designated official capital of Tanzania, is centrally located on the mainland. Dar es Salaam, however, remains the seat of most government administration, as well as being the largest city and port in the country.

East African country situated just south of the Equator. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean on the east and eight other nations: Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo (Kinshasa), Zambia, Malaŵi, and Mozambique. Tanzania was formed as a sovereign state in 1964 through the union of the theretofore separate states of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Mainland Tanganyika constitutes more than 99 percent of the combined territories' total area. Mafia Island is administered from the mainland, while Zanzibar and Pemba islands (Pemba Island) have a separate government administration. Dodoma, since 1974 the designated official capital of Tanzania, is centrally located on the mainland. Dar es Salaam, however, remains the seat of most government administration, as well as being the largest city and port in the country.

East African country situated just south of the Equator. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean on the east and eight other nations: Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo (Kinshasa), Zambia, Malaŵi, and Mozambique. Tanzania was formed as a sovereign state in 1964 through the union of the theretofore separate states of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Mainland Tanganyika constitutes more than 99 percent of the combined territories' total area. Mafia Island is administered from the mainland, while Zanzibar and Pemba islands (Pemba Island) have a separate government administration. Dodoma, since 1974 the designated official capital of Tanzania, is centrally located on the mainland. Dar es Salaam, however, remains the seat of most government administration, as well as being the largest city and port in the country.

East African country situated just south of the Equator. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean on the east and eight other nations: Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo (Kinshasa), Zambia, Malaŵi, and Mozambique. Tanzania was formed as a sovereign state in 1964 through the union of the theretofore separate states of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Mainland Tanganyika constitutes more than 99 percent of the combined territories' total area. Mafia Island is administered from the mainland, while Zanzibar and Pemba islands (Pemba Island) have a separate government administration. Dodoma, since 1974 the designated official capital of Tanzania, is centrally located on the mainland. Dar es Salaam, however, remains the seat of most government administration, as well as being the largest city and port in the country.The land: Tanzania mainland

Relief

Except for the narrow coastal belt of the mainland and the offshore islands, most of Tanzania lies above 600 feet (200 metres) in elevation. Vast stretches of plains and plateaus contrast with spectacular relief features, notably Africa's highest mountain, Kilimanjaro (19,340 feet 【5,895 metres】), and the world's second deepest lake, Lake Tanganyika (Tanganyika, Lake) (4,710 feet 【1,436 metres】 deep).

The East African Rift System runs in two north–south-trending branches through Tanzania, leaving many narrow, deep depressions that are often filled by lakes. One branch, the Western Rift Valley, runs along the western frontier and is marked by Lakes Tanganyika and Rukwa, while the other branch, the Eastern (or Great) Rift Valley, extends through central Tanzania from the Kenyan border in the region of Lakes Eyasi, Manyara, and Natron south to Lake Nyasa at the border with Mozambique. The Central Plateau, covering more than a third of the country, lies between the two branches.

Highlands associated with the Western Rift Valley are formed by the Ufipa Plateau, the Mbeya Range, and Rungwe Mountain in the southwestern corner of the country. From there the Southern Highlands run northeastward along the Great Rift to the Ukuguru and Nguru mountains northwest of Morogoro. Extending from the northern coast, the Usambara and Pare mountain chains run in a southeast-to-northwest direction, culminating in Kilimanjaro's lofty, snow-clad peak and continuing beyond to Mount Meru (Meru, Mount) (14,980 feet). Immediately to the west of Mount Meru, another chain of mountains begins, which includes the still-active volcano Ol Doinyo Lengai and the Ngorongoro Crater, the world's largest caldera, or volcanic depression. This chain extends through a corridor between Lake Eyasi and Lake Manyara toward Dodoma.

Highlands associated with the Western Rift Valley are formed by the Ufipa Plateau, the Mbeya Range, and Rungwe Mountain in the southwestern corner of the country. From there the Southern Highlands run northeastward along the Great Rift to the Ukuguru and Nguru mountains northwest of Morogoro. Extending from the northern coast, the Usambara and Pare mountain chains run in a southeast-to-northwest direction, culminating in Kilimanjaro's lofty, snow-clad peak and continuing beyond to Mount Meru (Meru, Mount) (14,980 feet). Immediately to the west of Mount Meru, another chain of mountains begins, which includes the still-active volcano Ol Doinyo Lengai and the Ngorongoro Crater, the world's largest caldera, or volcanic depression. This chain extends through a corridor between Lake Eyasi and Lake Manyara toward Dodoma.Drainage

Because of its numerous lakes, approximately 22,800 square miles of Tanzania's territory consists of inland water. Lake Victoria (Victoria, Lake), which ranks as the world's second largest freshwater lake, is not part of the Rift System. Interestingly, Tanzania has no big rivers, yet it forms the divide from which the three great rivers of the African continent rise—the Nile (Nile River), Congo (Congo River), and Zambezi (Zambezi River), which flow to the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Indian Ocean, respectively. Separated by the Central Plateau, the watersheds of these rivers do not meet.

All of Tanzania's major rivers—the Ruvuma (Ruvuma River), the Rufiji (Rufiji River), the Wami, and the Pangani—drain into the Indian Ocean. The largest, the Rufiji River, has a drainage system that extends over most of southern Tanzania. The Kagera flows into Lake Victoria, whereas other minor rivers flow into internal basins formed by the Great Rift Valley. With so many rivers, Tanzania is rich in hydroelectricity potential.

Soils

The variety of soils in Tanzania surpasses that of any other country in Africa. The reddish brown soils of volcanic origin in the highland areas are the most fertile. Many river basins also have fertile soils, but they are subject to flooding and require drainage control. The red and yellow tropical loams of the interior plateaus, on the other hand, are of moderate-to-poor fertility. In these regions, high temperatures and low rainfall encourage rapid rates of oxidation, which result in a low humus content in the soil and, consequently, a clayey texture rather than the desired crumblike structure of temperate soils. Also, tropical downpours, often short in duration but very intense, compact the soil; this causes drainage problems and leaches the soil of nutrients.

Climate

Tanzania is subject to a warm, equatorial climate modified by variations in elevation. The high amount of solar radiation throughout the year is associated with a limited seasonal fluctuation of temperature: the mean monthly variation is less than 9° F (5° C) at most stations. Ground frosts rarely occur below 8,200 feet.

Rainfall is highly seasonal, being influenced greatly by the annual migration of the intertropical convergence zone. Roughly half of Tanzania receives less than 30 inches (750 millimetres) of rainfall annually, an amount considered to be the minimum required for most forms of crop cultivation in the tropics. The Central Plateau, the driest area, with less than 20 inches per year on average, experiences a single rainy season between December and May. Rainfall is heavier on the coast, where there are two peaks of rainfall in October–November and April–May. The offshore islands and many highland areas have high annual rainfall totals of over 60 inches.

Plant and animal life

Forests grow in the highland areas where there is high rainfall and no marked dry season. The western and southern plateaus are primarily miombo woodland, consisting of an open cover of trees, notably Brachystegia, Isoberlinia, Acacia, and Combretum. In areas of less rainfall (16–32 inches), bushland and thicket are found. In the floodplain areas, wooded grassland with a canopy cover of less than 50 percent has been created by poor drainage and by the practice of burning for agriculture and animal grazing. Similarly, grassland appears where there is a lack of good drainage. For example, the famous Serengeti Plain owes its grasslands to a calcrete, or calcium-rich hardpan, deposited close to the surface by evaporated rainwater. Swamps are found in areas of perennial flooding. Desert and semidesert conditions range from an Alpine type at high altitudes to saline deserts in poorly drained areas and arid deserts in areas of extremely low rainfall.

Due to the historically low density of human settlement, Tanzania is home to an exceptionally rich array of wildlife. Large herds of hoofed animals—most spectacularly the wildebeest, as well as the zebra, giraffe, buffalo, gazelle, eland, dik-dik, and kudu—are found in most of the country's numerous game parks. Predators include hyenas, wild dogs, and the big cats—lions, leopards, and cheetahs. Crocodiles and hippopotamuses are common on riverbanks and lakeshores. The government has taken special measures to protect the rhinoceros and elephant, which have fallen victim to poachers. Small bands of chimpanzees inhabit Gombe National Park along Lake Tanganyika. Nearly 1,500 varieties of birds have been reported, and there are numerous species of snakes and lizards.

Settlement patterns

The two most important factors influencing the regional pattern of human settlement are rainfall and the incidence of tsetse fly. The tsetse, which thrives on wild game in miombo woodlands, is the carrier of Trypanosoma, a blood parasite that causes sleeping sickness in cattle and people. Tsetse infestation makes human settlement hazardous in areas of moderate rainfall, so that areas of low and unreliable rainfall are more densely populated than would otherwise be the case. The insect does not pose a threat to areas of high rainfall and high population density.

Population is concentrated in the highlands of the Mbeya Range, Kilimanjaro, and the Bukoba area west of Lake Victoria, on the cultivation steppe south of Lake Victoria, in the moderately high-rainfall region of Mtwara on the southern coast, and in the urban area of Dar es Salaam. These areas are all located on the perimeter of the country. The influence of the central rail line is clearly evident in the corridor of moderate population density extending from Dar es Salaam to Lake Victoria. Three sparsely populated areas stand out: the arid area of Arusha in the north and the two large tsetse-infested areas centred around Tabora in the west and Lindi and Songea in the south.

Regional variations in agricultural productivity are strongly related to the pressure of population on the land. Shifting (shifting agriculture) cultivation, which involves rotating crops annually and leaving some fields to lie fallow for 20 years or more, was traditionally the means of renewing the fertility of the soil throughout Tanzania (with the exception of the more fertile and densely populated highland areas). A settlement pattern of widely dispersed, isolated farmsteads resulted from this practice. As the rural population expanded, however, fallow periods became shorter, and consequently soil fertility and crop yields suffered. In order to raise productivity, during the 1960s and '70s the government tried to bring about the use of improved agricultural methods, equipment, and fertilizer through the nucleation of rural settlements. First, the ujamaa (or “familyhood”) policy of the 1960s supported collectivized agriculture in a number of government-sponsored planned settlements. These settlements were over-reliant on government finance and gradually dwindled in number. On a much larger scale, the “villagization” program of the 1970s moved millions of peasants into nucleated villages of 250 households or more. By 1978 there were more than 7,500 villages, in comparison to only about 800 in 1969. Villagization was aimed not at collectivizing agriculture but at facilitating the distribution of agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and improved seeds as well as making social services more accessible to the rural population.

Only about 15 percent of the population lives in urban areas, and one-third of the urban population resides in Dar es Salaam, a city of more than one million people. Bagamoyo and Tabora, old towns connected with the 19th-century Arab slave trade, have stagnated. The fortunes of Tanga, the second largest city during the British colonial period, have been tied to the export of sisal; as that has declined, the city has grown very slowly, although it remains the country's third largest city. Mwanza, Mbeya, and Arusha have thrived as trading centres remote from Dar es Salaam, and the growth of Morogoro and Moshi reflects their rich agricultural hinterlands.

The land: Zanzibar and Pemba

Relief

Low-lying Pemba, whose highest point reaches an elevation of 311 feet, and Zanzibar, which reaches 390 feet, are islands whose structure consists of coralline rocks. The west and northwest of Zanzibar consist of several ridges rising above 200 feet, but nearly two-thirds of the south and east are low-lying. Pemba appears hilly because the level central ridge has been gullied and eroded by streams draining into numerous creeks. On Zanzibar Island short streams drain mostly to the north and west. The few streams in the east disappear into the porous coralline rock.

Soils

Among the 10 types of soils recognized in Zanzibar are fertile sandy loams and deep red earths, which occur on high ground; on valley bottoms, less fertile gray and yellow sandy soils are found. The eight soil types in Pemba include brown loams; pockets of infertile sands are found on the plains.

Climate

Zanzibar and Pemba have rainfall of 60 inches and 80 inches, respectively. The rainfall is highest in April and May, lowest in November and December. Humidity is high. The average temperature is 81° F (27° C) in Zanzibar and 79° F (26° C) in Pemba; the annual temperature ranges are small.

Vegetation

Long human occupation has resulted in the clearance of most of the forests, which have been replaced with coconuts, cloves, bananas, citrus, and other crops. On the eastern side of the islands, especially on Zanzibar, there is bush (scrub).

Animal life

Although there is some difference between the animal life of the two islands, it is generally similar to that on the mainland. Animal life common to both islands includes monkeys, civet cats, and mongooses. More than 100 species of birds have been recorded in Zanzibar.

Rural settlements

The rural settlements—and the life in them—changed drastically after the nationalization of land in 1964 and subsequent agricultural reforms. By 1970, large plantations of cloves and coconuts, once almost exclusively the property of fewer than 50 Arab families, had been redistributed. The production of food crops, especially rice, is being encouraged. Fishing villages are still important in the east.

Urban settlements

The city of Zanzibar is still primarily a Muslim town, although the distinctive mode of life and culture, reminiscent of an Eastern commercial centre, has almost disappeared since the downfall of the Arab oligarchy in 1964. The hub of civic life is moving from Stone Town with its narrow lanes to a new town with modern buildings and amenities at Ngambo, the former African quarter. Kilimani, Bambi, and Chaani are being developed into new rural towns; a similar change is taking place in Pemba at Mkoani, Chake Chake, and Wete.

The people: Tanzania mainland

Ethnic composition

Tanzania is extremely heterogeneous, with more than 120 different indigenous African peoples as well as small groups of Asians and Europeans. As early as 5000 BC, San-type hunting bands inhabited the country. The Sandawe hunters of northern Tanzania are thought to be their descendants. By 1000 BC, agriculture and pastoral practices were being introduced through the migration of Cushitic people from Ethiopia. The Iraqw, Mbugu, Gorowa, and Burungi have Cushitic origins. About AD 500, iron-using Bantu agriculturalists coming from the west and south started displacing or absorbing the San hunters and gatherers; at roughly the same time, Nilotic pastoralists entered the area from the southern Sudan. Today the majority of Tanzanians are of Bantu (Bantu languages) descent; the Sukuma constitute the largest group, and others are the Nyamwezi, Hehe, Nyakyusa, Makonde, Yao, Haya, Chaga, Gogo, and Ha. Nilotic peoples are represented by the Masai, Arusha, Samburu, and Baraguyu. No one group has been politically or culturally dominant, although the tribes that were subject to Christian missionary influence and Western education during the colonial period (notably the Chaga and Haya) are now disproportionately represented in the government administration and cash economy.

There are also Asian and European minorities. During the colonial period, Asian immigration was encouraged, and Asians dominated the up-country produce trade. Coming mostly from Gujurāt in India, they form several groups distinguished by religious belief: the Ismāʿīlīs, Bohrās, Sikhs, Punjabis, and Goans. Since independence the Asian population has steadily declined due to emigration. The European population, never large because Tanganyika was not a settler colony, was made up primarily of English, Germans, and Greeks. In the postindependence period, a proliferation of different European, North American, and Japanese expatriates connected with foreign aid projects have made Tanzania their temporary residence.

Language

Swahili (Swahili language) is the national language. Virtually all Tanzanians speak the language, and it is used as the medium of instruction in the first seven years of primary education. English, the country's second official language (together with Swahili), is the medium of instruction at further levels of education and is commonly used by the government in official business. Most African Tanzanians speak their traditional tribal language as well. The main languages spoken by the Asian minorities are Gujarati, Hindi, Punjabi, and Urdu.

Religion

Roughly one-third of the population is Muslim, another third professes Christianity, and the remainder is considered to hold animist beliefs. The division is usually not as clear as official statistics suggest, since many rural Tanzanians adhere to elements of their traditional animistic religions while practicing their Islāmic or Christian faith. A wide array of Christianity is represented, notably Lutheranism and Roman Catholicism. Among Muslims, both the Sunnite and Shīʿite sects are represented. The majority of Asian Muslims are Ismāʿīlī Khōjās under the Aga Khan's spiritual leadership. In addition, there are Asian adherents to Hinduism, Jainism, and Roman Catholicism.

Demographic trends

Tanzania's population growth rate is one of the highest in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite great improvements since the 1950s, the infant and child mortality rates remain high, but fertility is high as well. Nearly 50 percent of Tanzanians are under the age of 15. Life expectancy, at about 53 years, is above average for the subcontinent.

The people: Zanzibar and Pemba

Language

Swahili is the principal language in Zanzibar and Pemba. The classical dialect is Kiunguja. Arabic (Arabic language) is also important because of long-established Islāmic tradition, past Arab overlordship, and the presence of a large Arab-speaking minority. Among the Asian communities, the chief languages are Gujarati, Kutchi, and Hindustani. English, taught in schools, is widely used.

Ethnic groups

There are several groups of Africans, nearly one-third of whom are recent arrivals from the mainland. Indigenous Bantu groups, consisting of the Pemba in Pemba and the Hadimu and Tumbatu in Zanzibar, have absorbed the settlers who came from Persia in the 10th century. These groups and some of the descendants of slaves call themselves Shirazi. There are also small enclaves of Comorians and Somalis. Arab settlements were also established early, and intermarriage with the local people took place. Later Arab arrivals came from Oman and constituted an elite. The poorer recent immigrants from Oman are known as Manga. The Asians, now forming a very small minority, may be divided into Muslim and non-Muslim groups.

Religion

Almost the whole of the Arab and the African peoples of Zanzibar profess the Islāmic (Islāmic world) faith. Traditional African beliefs are also found existing in conjunction with Islām. Among Muslims, the Sunnite sect is preferred by the indigenous people.

The economy

The Tanzanian economy is overwhelmingly agrarian in nature and reflects the leadership's political commitment to socialist development and central planning. Agriculture constitutes over half of the gross domestic product (GDP) and some 80 percent of export earnings, and it provides a livelihood for about nine-tenths of the economically active population. Industry accounts for less than 10 percent of the GDP, and mining less than 1 percent, whereas services, including public administration, produce approximately one-third of the GDP. A number of industries and public services were nationalized at the time of the Arusha Declaration in 1967, when the intention to build a socialist state was announced.

Beginning in 1979 and continuing throughout the 1980s, the international oil price rise, the country's declining terms of trade, and the sluggishness of the domestic economy brought about rapid inflation, the emergence of an unofficial market (consisting of the smuggling of goods abroad in order to avoid taxes and price controls), and a government fiscal crisis. Despite attempts to cut imports to the barest minimum, the trade deficit widened to an unprecedented level, and the balance-of-payments problem became so acute that development projects had to be suspended. This economic crisis forced the government to secure a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1986. The loan's conditions required the elimination of subsidies and price controls as well as some social services and staff positions in state-run enterprises. Thereafter, the government continued to implement measures intended to create a mixed economy and reduce the extent of the untaxable unofficial markets.

Agriculture

The major food crops are corn, rice, sorghum, millet, bananas, cassava, sweet potatoes, barley, potatoes, and wheat. Corn and rice are the preferred cereals, whereas cassava and sweet potatoes are used as famine-prevention crops owing to their drought-resistant qualities. In some areas food crops are sold as cash crops. Peasants in the Ruvuma and Rukwa regions, for example, have specialized in commercial corn production, and in riverine areas, especially along the Rufiji, rice is sold.

Export cash crops provide the major source of foreign exchange for the country. Coffee and cotton are by far the most important in this respect, but exports of tea, cashew nuts, tobacco, and sisal are also substantial. Cloves are Zanzibar's main export. Once the source of over 90 percent of the world's cloves, Zanzibar now produces only about 10 percent of the international supply.

The villagization program of the mid-1970s was followed by government efforts to distribute improved seed corn and fertilizers through the new village administrations, but timely distribution of such agricultural inputs was largely thwarted by the logistical problems of transporting them to the villages. Nevertheless, increased yields, attributed to the use of chemical fertilizers, have been achieved in peasant corn production in the south and southwestern regions.

Industry

Tanzania's industry is based on the processing of its agricultural goods and on import substitution—that is, the manufacture (often from imported materials and parts) of products that were once purchased from abroad. The principal industries are food processing, textiles, brewing, and cigarettes. Production of clothing, footwear, tires, batteries, and bottles takes place as well. There is also a hot-rolling steel mill, a factory producing asbestos cement sheets, a bicycle factory, and a large pulp and paper mill.

A strategy to lay the foundation for the rapid growth of such basic industries as steel, chemicals, rubber, and textiles was thwarted by the national economic crisis of the 1980s. The large amounts of imported materials, parts, and capital equipment necessary to implement such a policy could not be paid for, owing to the country's lack of foreign exchange. Standby credit facilities from the IMF provided the capital investment needed to initiate a rehabilitation of industry.

Resources

Tanzania mines diamonds, gold, kaolin, gypsum, tin, and various gemstones, including tanzanite. There are large exploitable deposits of coal in the southwest, phosphate deposits in Arusha, and nickel in the Kagera region. Natural gas has been discovered at Songo Songo Island. Several international companies have been involved in onshore and offshore petroleum exploration.

Tanzania's native forests are primarily composed of hardwoods, but softwood production is increasing. A large pulp and paper mill at Mufindi is supplied by the extensive softwood forest nearby at Sao Hill. Because firewood and charcoal are the major domestic fuels, there is growing concern about the deforestation of land in the hinterland of Dar es Salaam and Tanzania's other large towns.

Several lakes, especially Lake Victoria, are important sources of fish. Prawns are commercially fished in the Rufiji River delta, but coastal fishery is primarily of an artisanal nature.

Finance and trade

All private banks were nationalized between 1967 and 1992, but since then private banks (including branches of foreign-owned banks) have been allowed to open. The state-run Bank of Tanzania operates as the central bank; it manages the country's finances and issues the currency, the Tanzanian shilling.

Transportation

Transport in Tanzania spans a wide spectrum, from the motorized means made possible by roads, railways, seaports, and airfields to the traditional carrying of loads by animals and people. It is estimated that the average peasant household carries by headload approximately 56 ton-miles (90 ton-kilometres) of firewood, water, and crops per year.

Roads are by far the most important nontraditional mode of transport, carrying some 70 percent of total traffic. The road network extends to all parts of the country, but it is densest along the coast and southeast of Lake Victoria. The country's percentage of roads paved is one of the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa. The Tanzam Highway, opened in the early 1970s between Dar es Salaam and Zambia, has significantly reduced the isolation of southern Tanzania. A newer highway intersects it at Makambako and proceeds southward through the southern highlands to Songea. Government efforts have been placed on rehabilitating the trunk road system, which deteriorated with a decline in the importation of maintenance materials during the economic crisis.

Dar es Salaam port, with its deep-water berths, handles about three-fourths of all ships calling at Tanzanian ports. The remainder go primarily to Tanga, Mtwara, and the port of the city of Zanzibar. The Tanzania Coastal Shipping Line offers transport services along the coast; a passenger ferry operates between Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar.

The Air Tanzania Corporation provides internal air services as well as international flights to destinations in central and southern Africa, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean. There are international airports at Dar es Salaam, Kilimanjaro, and Zanzibar, but most scheduled international flights land in Dar es Salaam.

The railway system dates back to the pre-World War I, German-built Central Railway Line, which bisects the country between Dar es Salaam and Kigoma, and the Tanga-to-Moshi railway. Today there is also a branch between these two lines, and another line connects Mwanza with Tabora on the Central Line. The TAZARA rail line, running between Dar es Salaam and Kapiri-Mposhi on the Zambian border, was built with Chinese aid in the early 1970s. It provided the main outlet to the sea for Zambia's copper exports prior to the political changes in South Africa in the 1990s that opened southern transport routes for Tanzania's landlocked neighbour.

Administration and social conditions

The government

The Interim Constitution of 1965 established the United Republic of Tanzania through the merger of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, until then separate and independent countries. A permanent constitution for the United Republic was approved in 1977 and amended in 1984 to include a bill of rights.

Zanzibar has a separate constitution, approved in 1979 and amended in 1985. The executive branch is composed of an elected president and a cabinet called the Supreme Revolutionary Council. Zanzibar's parliament, the House of Representatives, is made up of elected and appointed members. These political bodies deal with matters internal to Zanzibar. Since the union with Tanganyika, some segments of Zanzibari society have occasionally demanded greater autonomy from the mainland.

The president of the United Republic is the head of state and commander in chief of the armed forces. The cabinet of ministers is advisory to the president. Prior to 1995 it included two vice presidents: the prime minister, who is appointed by the president and acts as the leader of the cabinet, and the president of Zanzibar. Since then an amendment to the constitution, which was approved in 1994 and took effect after the 1995 general election, rescinded the stipulation that called for the president of Zanzibar to serve as a vice president.

According to the 1984 constitutional amendments, most members (216 in the 1990 election) of the National Assembly are directly elected. Many seats also are allocated to ex-officio, nominated, and indirectly elected members—including those seats reserved for women, representatives of mass organizations, and the president's nominees. The National Assembly has a term of five years but can be dissolved by the president before this term expires.

By law Tanzania was a one-party state until 1992, when the constitution was amended to establish a multiparty political process. In 1977 the Tanganyika African Nationalist Union, which had led the colony to independence, and the Afro-Shirazi Party of Zanzibar, which had taken power after a coup in 1964, were amalgamated into the Revolutionary Party (Chama cha Mapinduzi; CCM). Prior to the 1992 amendment, the CCM dominated all aspects of political life, and there was no clear separation of party and government personnel at regional and district levels. By the time of the first national multiparty election in 1995, more than a dozen opposition political movements were officially registered. The CCM's involvement in local government and other local affairs also began to wane, particularly its administration of the 10-cell neighbourhood watch program (with each cell varying in size from single-family homes to large apartment buildings).

For administrative purposes, mainland Tanzania is divided into 20 regions. Each region is administered by a commissioner who is appointed by the central government. At district, division, and ward levels, there are popularly elected councils with appointed executive officers.

The judiciary

Tanzania's judiciary is appointed by the president in consultation with the chief justice. Judges cannot be dismissed except on the grounds of misbehaviour or incapacity. A network of primary and district courts has been established throughout the country. English, Islāmic, and customary laws have been absorbed into the legal system. In Zanzibar the highest judicial authority is the Supreme Council. Muslim courts deal with marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Education

The government-supported education system has three levels: primary (seven years), secondary (four to six years), and university, as well as vocational training schools. During the mid-1970s universal primary education was made mandatory, resulting in a vast increase in primary-school children. Popular pressure for the expansion of secondary schools has outstripped the availability of government finance. As a result, private secondary schools sponsored by religious institutions and, most notably, by parents themselves have expanded in number. There are two universities, the University of Dar es Salaam (1961), formerly part of the University of East Africa, and Sokoine University of Agriculture (1984). Extensive adult education has focused on eradicating illiteracy, and, as a result, Tanzania has one of the highest literacy rates in Africa.

Health and welfare

National and local governments support a network of village dispensaries and rural health centres; hospitals are located in the urban areas. Private doctors and religious organizations provide medical facilities as well.

The emphasis of national health policy has been on preventive medicine, especially better nutrition, maternal and child health, environmental sanitation, and the prevention and control of communicable diseases. The main communicable diseases are poliomyelitis, leprosy, tuberculosis, dysentery, enteric fevers, and AIDS. Environmental diseases include malaria, sleeping sickness, bilharzia, and onchocerciasis (river blindness). Inadequate nutrition, particularly of children, is a major concern. Improvements in health and reduction of mortality rates have resulted from the provision of medical care to the rural population and from an inoculation program for children.

Cultural life

Olduvai Gorge, in the Great Rift Valley, is the site of the discovery of some of the earliest known remains of human ancestry, dating back 1,750,000 years. The ancient in-migration of Cushitic, Nilotic, and Bantu peoples, displacing the native San-type population, resulted in a complex agglomeration of tribal communities practicing complementary forms of pastoral and agricultural livelihoods. In the last 500 years, Portuguese, Arab, Indian, German, and British traders and colonists have added to the mosaic. Today Tanzania's multiethnic and multiracial population practices a variety of traditions and customs that form a rich cultural heritage.

The role of kin is central to Tanzanian social and recreational life. Visiting kin on joyous and sorrowful family occasions is given high priority despite the inconvenience caused by a relatively undeveloped transport system. Educated members of the extended family are frequently held responsible for the education and welfare of younger siblings.

Football (soccer) is a popular sport. In international competitions, Tanzanian sportsmen have excelled in long-distance running.

Oral storytelling traditions and tribal dancing are an important part of the cultural life of the rural population. The University of Dar es Salaam has an active theatre arts group. Among the visual arts, Makonde carvers from southern Tanzania are renowned for their abstract ebony carvings, and Zanzibar is famous for its elaborately carved doors and Arab chests. Basket weaving, pottery, and musical instrument making are prevalent in many rural areas.

Tanzania has government-owned Swahili and English daily newspapers. The radio, more than newspapers or television, is the medium through which the rural population receives national and international news. The radio has been extensively used by the government for the promotion of adult literacy, better nutrition, and ecological conservation.

History

Tanganyika

Early exploration

Most of the known history of Tanganyika before the 19th century concerns the coastal area, although the interior has a number of important prehistoric sites, including the Olduvai Gorge. Trading contacts between Arabia (Arab) and the East African coast existed by the 1st century AD, and there are indications of connections with India. The coastal trading centres were mainly Arab settlements, and relations between the Arabs and their African neighbours appear to have been fairly friendly. After the arrival of the Portuguese in the late 15th century, the position of the Arabs was gradually undermined, but the Portuguese made little attempt to penetrate into the interior. They lost their foothold north of the Ruvuma River early in the 18th century as a result of an alliance between the coastal Arabs and the ruler of Muscat on the Arabian Peninsula. This link remained extremely tenuous, however, until French interest in the slave trade from the ancient town of Kilwa, on the Tanganyikan coast, revived the trade in 1776. Attention by the French also aroused the sultan of Muscat's interest in the economic possibilities of the East African coast, and a new Omani governor was appointed at Kilwa. For some time most of the slaves came from the Kilwa hinterland, and until the 19th century such contacts as existed between the coast and the interior were due mainly to African caravans from the interior.

In their constant search for slaves, Arab traders began to penetrate farther into the interior, more particularly in the southeast toward Lake Nyasa. Farther north two merchants from India followed the tribal trade routes to reach the country of the Nyamwezi about 1825. Along this route ivory appears to have been as great an attraction as slaves, and Saʿīd ibn Sulṭān himself, after the transfer of his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar, gave every encouragement to the Arabs to pursue these trading possibilities. From the Nyamwezi country the Arabs pressed on to Lake Tanganyika in the early 1840s. Tabora (or Kazé, as it was then called) and Ujiji, on Lake Tanganyika, became important trading centres, and a number of Arabs made their homes there. They did not annex these territories but occasionally ejected hostile chieftains. Mirambo, an African chief who built for himself a temporary empire to the west of Tabora in the 1860s and '70s, effectively blocked the Arab trade routes when they refused to pay him tribute. His empire was purely a personal one, however, and collapsed on his death in 1884.

In their constant search for slaves, Arab traders began to penetrate farther into the interior, more particularly in the southeast toward Lake Nyasa. Farther north two merchants from India followed the tribal trade routes to reach the country of the Nyamwezi about 1825. Along this route ivory appears to have been as great an attraction as slaves, and Saʿīd ibn Sulṭān himself, after the transfer of his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar, gave every encouragement to the Arabs to pursue these trading possibilities. From the Nyamwezi country the Arabs pressed on to Lake Tanganyika in the early 1840s. Tabora (or Kazé, as it was then called) and Ujiji, on Lake Tanganyika, became important trading centres, and a number of Arabs made their homes there. They did not annex these territories but occasionally ejected hostile chieftains. Mirambo, an African chief who built for himself a temporary empire to the west of Tabora in the 1860s and '70s, effectively blocked the Arab trade routes when they refused to pay him tribute. His empire was purely a personal one, however, and collapsed on his death in 1884.The first Europeans to show an interest in Tanganyika in the 19th century were missionaries of the Church Missionary Society, Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann (Rebmann, Johannes), who in the late 1840s reached Kilimanjaro. It was a fellow missionary, Jakob Erhardt, whose famous “slug” map (showing, on Arab information, a vast, shapeless, inland lake) helped stimulate the interest of the British explorers Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke. They traveled from Bagamoyo to Lake Tanganyika in 1857–58, and Speke also saw Lake Victoria. This expedition was followed by Speke's second journey, in 1860, in the company of J.A. Grant, to justify the former's claim that the Nile rose in Lake Victoria. These primarily geographic explorations were followed by the activities of David Livingstone (Livingstone, David), who in 1866 set out on his last journey for Lake Nyasa. Livingstone's object was to expose the horrors of the slave trade and, by opening up legitimate trade with the interior, to destroy the slave trade at its roots. Livingstone's journey led to the later expeditions of H.M. Stanley and V.L. Cameron. Spurred on by Livingstone's work and example, a number of missionary societies began to take an interest in East Africa after 1860.

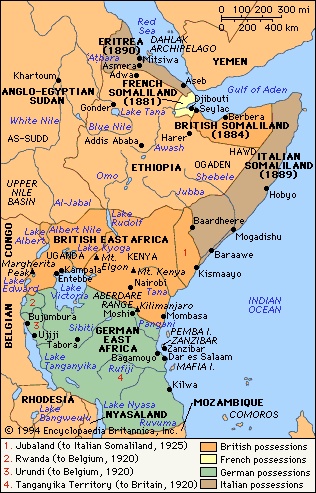

German East Africa

It was left to Germany, with its newly awakened interest in colonial expansion, to open up the country to European influences. The first agent of German imperialism was Carl Peters (Peters, Carl), who, with Joachim, Count Pfeil and Karl Juhlke, evaded the sultan of Zanzibar late in 1884 to land on the mainland. He made a number of “contracts” in the Usambara area by which several chiefs were said to have surrendered their territory to him. Peters' activities were confirmed by Bismarck. By the Anglo-German Agreement of 1886 the sultan of Zanzibar's vaguely substantiated claims to dominion on the mainland were limited to a 10-mile-wide coastal strip, and Britain and Germany divided the hinterland between them as spheres of influence, the region to the south becoming known as German East Africa. Following the example of the British to the north, the Germans obtained a lease of the coastal strip from the sultan in 1888, but their tactlessness and fear of commercial competition led to a Muslim rising in August 1888. The rebellion was put down only after the intervention of the imperial German government and with the assistance of the British navy.

It was left to Germany, with its newly awakened interest in colonial expansion, to open up the country to European influences. The first agent of German imperialism was Carl Peters (Peters, Carl), who, with Joachim, Count Pfeil and Karl Juhlke, evaded the sultan of Zanzibar late in 1884 to land on the mainland. He made a number of “contracts” in the Usambara area by which several chiefs were said to have surrendered their territory to him. Peters' activities were confirmed by Bismarck. By the Anglo-German Agreement of 1886 the sultan of Zanzibar's vaguely substantiated claims to dominion on the mainland were limited to a 10-mile-wide coastal strip, and Britain and Germany divided the hinterland between them as spheres of influence, the region to the south becoming known as German East Africa. Following the example of the British to the north, the Germans obtained a lease of the coastal strip from the sultan in 1888, but their tactlessness and fear of commercial competition led to a Muslim rising in August 1888. The rebellion was put down only after the intervention of the imperial German government and with the assistance of the British navy.Recognizing the administrative inability of the German East Africa Company, which had theretofore ruled the country, the German government declared a protectorate over its sphere of influence in 1891 and over the coastal strip, where the company had bought out the sultan's rights. Germany was anxious to exploit the resources of its new dependency, but lack of communications at first restricted development to the coastal area. The introduction of sisal from Florida in 1892 by the German agronomist Richard Hindorff marked the beginning of the territory's most valuable industry, which was encouraged by the development of a railway from the new capital of Dar es Salaam to Lake Tanganyika. In 1896 work began on the construction of a railway running northeastward from Tanga to Moshi, which it reached in 1912. This successfully encouraged the pioneer coffee-growing activities on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. Wild rubber tapped by Africans, together with plantation-grown rubber, contributed to the economic development of the colony. The government also supplied good-quality cottonseed free to African growers and sold it cheaply to European planters. The administration tried to make good the lack of clerks and minor craftsmen by encouraging the development of schools, an activity in which various missionary societies were already engaged.

The enforcement of German overlordship was strongly resisted, but control was established by the beginning of the 20th century. Almost at once came a reaction to German methods of administration, the outbreak of the Maji Maji rising in 1905. Although there was little organization behind it, the rising spread over a considerable portion of southeastern Tanganyika and was not finally suppressed until 1907. It led to a reappraisal of German policy in East Africa. The imperial government had attempted to protect African land rights in 1895 but had failed in its objective in the Kilimanjaro area. Similarly, liberal labour legislation had not been properly implemented. The German government set up a separate Colonial Department in 1907, and more money was invested in East Africa. A more liberal form of administration rapidly replaced the previous semimilitary system.

World War I put an end to all German experiments. Blockaded by the British (British Empire) navy, the country could neither export produce nor get help from Germany. The British advance into German territory continued steadily from 1916 until the whole country was eventually occupied. The effects of the war upon Germany's achievements in East Africa were disastrous; the administration and economy were completely disrupted. In these circumstances the Africans reverted to their old social systems and their old form of subsistence farming. Under the Treaty of Versailles (1919), Britain received a League of Nations mandate to administer the territory except for Ruanda-Urundi, which came under Belgian administration, and the Kionga triangle, which went to Portugal.

Tanganyika Territory

Sir Horace Byatt, administrator of the captured territory and, from 1920 to 1924, first British governor and commander in chief of Tanganyika Territory (as it was then renamed), enforced a period of recuperation before new development plans were set on foot. A Land Ordinance (1923) ensured that African land rights were secure. Sir Donald Cameron, governor from 1925 to 1931, infused a new vigour into the country. He reorganized the system of native administration by the Native Authority Ordinance (1926) and the Native Courts Ordinance (1929). His object was to build up local government on the basis of traditional authorities, an aim that he pursued with doctrinaire enthusiasm and success. He attempted to silence the criticisms by Europeans that had been leveled against his predecessor by urging the creation of a Legislative Council in 1926 with a reasonable number of nonofficial members, both European and Asian. In his campaign to develop the country's economy, Cameron won a victory over opposition from Kenya by gaining the British government's approval for an extension of the Central Railway Line from Tabora to Mwanza (1928). His attitude toward European settlers was determined by their potential contribution to the country's economy. He was, therefore, surprised by the British government's reluctance to permit settlement in Tanganyika. The economic depression after 1929 resulted in the curtailment of many of Cameron's development proposals. In the 1930s, too, Tanganyika was hampered by fears that it might he handed back to Germany in response to Hitler's demands for overseas possessions.

At the outbreak of World War II Tanganyika's main task was to make itself as independent as possible of imported goods. Inevitably the retrenchment evident in the 1930s became still more severe, and, while prices for primary products soared, the value of money depreciated proportionately. Tanganyika's main objective after the war was to ensure that its program for economic recovery and development should go ahead. The continuing demand for primary produce strengthened the country's financial position. The chief item in the development program was a plan to devote 3 million acres (1.2 million hectares) of land to the production of peanuts (the Groundnuts Scheme). The plan, which was to be financed by the British government, was to cost £25 million, and, in addition, a further £4.5 million would be required for the construction of a railway in southern Tanganyika. It failed because of the lack of adequate preliminary investigations and was subsequently carried out on a greatly reduced scale.

Constitutionally, the most important immediate postwar development was the British government's decision to place Tanganyika under UN trusteeship (1947). Under the terms of the trusteeship agreement, Britain was called upon to develop the political life of the territory, which, however, only gradually began to take shape in the 1950s with the growth of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). The first two African members had been nominated to the Legislative Council in December 1945. This number was subsequently increased to four, with three Asian nonofficial members and four Europeans. An official majority was retained. In an important advance in 1955, the three races were given parity of representation on the unofficial side of the council with 10 nominated members each, and for a time it seemed as if this basis would persist. The first elections to the unofficial side of the council, however, enabled TANU to show its strength, for even among the European and Asian candidates only those supported by TANU were elected.

A constitutional committee in 1959 unanimously recommended that after the elections in 1960 a large majority of the members of both sides of the council should be Africans and that elected members should form the basis of the government. The approval of the British colonial secretary was obtained for these proposals in December 1959, and in September 1960 a predominantly TANU government took office. The emergence of this party and its triumph over the political apathy of the people were largely due to the leadership of Julius Nyerere (Nyerere, Julius). Tanganyika became independent on December 9, 1961, with Nyerere as its first prime minister.

Zanzibar

The history of Zanzibar has been to a large extent shaped by the monsoons (prevailing trade winds) and by its proximity to the continent. The regular annual recurrence of the monsoons has made possible its close connection with India and the countries bordering the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. Its proximity to the continent has made it a suitable jumping-off point for trading and exploring ventures not only along the coast but also into the interior.

Portuguese and Omani domination

Though the first references to Zanzibar occur only after the rise of Islam, there would appear to be little doubt that its close connection with southern Arabia and the countries bordering the Persian Gulf began before the Christian era. At the beginning of the 13th century, the Arab geographer Yakut recorded that the people of Lenguja (namely, Unguja, the Swahili name for Zanzibar) had taken refuge from their enemies on Tumbatu, the inhabitants of which were Muslims.

Though the first references to Zanzibar occur only after the rise of Islam, there would appear to be little doubt that its close connection with southern Arabia and the countries bordering the Persian Gulf began before the Christian era. At the beginning of the 13th century, the Arab geographer Yakut recorded that the people of Lenguja (namely, Unguja, the Swahili name for Zanzibar) had taken refuge from their enemies on Tumbatu, the inhabitants of which were Muslims.In 1498 Vasco da Gama (Gama, Vasco da) visited Malindi, and in 1503 Zanzibar Island was attacked and made tributary by the Portuguese. It appears to have remained in that condition for about a quarter of a century. Thereafter the relations between the rulers of Zanzibar and the Portuguese seem to have been those of allies, the people of Zanzibar more than once cooperating with the Portuguese in attacks upon Mombasa. In 1571 the “king” of Zanzibar, in gratitude for Portuguese assistance in expelling certain African invaders, donated the island to his allies, but the donation was never implemented. A Portuguese trading factory and an Augustinian mission were established on the site of the modern city of Zanzibar, and a few Portuguese appear also to have settled as farmers in different parts of the island. The first English ship to visit Zanzibar (1591–92) was the Edward Bonaventure, captained by Sir James Lancaster (Lancaster, Sir James).

When the Arabs captured Mombasa in 1698, all these settlements were abandoned and (except for a brief Portuguese reoccupation in 1728) Zanzibar and Pemba came under the domination of the Arab rulers of Oman. For more than a century those rulers left the government of Zanzibar to local hakims (governors). The first sultan to take up residence in Zanzibar was Sayyid Saʿīd ibn Sulṭān, who after several short visits settled there soon after 1830 and subsequently greatly extended his influence along the East African coast. On Saʿīd's death in 1856 his son Majīd succeeded to his African dominions, while another son, Thuwayn, succeeded to Oman.

As a result of an award made in 1860 by Lord Canning (Canning, Charles John Canning, Earl), governor general of India, the former African dominions of Saʿīd were declared to be independent of Oman. Majīd died in 1870 and was succeeded by his brother Barghash. Toward the end of the latter's reign his claims to dominion on the mainland were restricted by Britain, France, and Germany to a 10-mile-wide coastal strip, the administration of which was subsequently shared by Germany and Britain. Barghash died in 1888. Both he and Majīd had acted largely under the influence of Sir John Kirk (Kirk, Sir John), who was British consular representative at Zanzibar from 1866 to 1887. It was by Kirk's efforts that Barghash consented in 1873 to a treaty for the suppression of the slave trade.

British protectorate

In 1890 what was left of the sultanate was proclaimed a British protectorate, and in 1891 a constitutional government was instituted under British auspices, with Sir Lloyd Mathews as first minister. In August 1896, on the death of the ruling sultan, Ḥamad ibn Thuwayn, the royal palace at Zanzibar was seized by Khālid, a son of Sultan Barghash, who proclaimed himself sultan. The British government disapproved, and, as he refused to submit, the palace was bombarded by British warships. Khālid escaped and took refuge at the German consulate, whence he was conveyed to German East Africa. Ḥamud ibn Moḥammed was then installed as sultan (August 27, 1896). In 1897 the legal status of slavery was finally abolished. In 1913 the control of the protectorate passed from the Foreign Office to the Colonial Office, when the posts of consul general and first minister were merged into that of British resident. At the same time, a Protectorate Council was constituted as an advisory body. In 1926 the advisory council was replaced by nominated executive and legislative councils.

Khalīfa ibn Harūb became sultan in 1911. He was the leading Muslim prince in East Africa, and his moderating influence did much to steady Muslim opinion in that part of Africa at times of political crisis, especially during the two world wars. He died on October 9, 1960, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir Abdullah ibn Khalīfa.

In November 1960 the British Parliament approved a new constitution for Zanzibar. The first elections to the Legislative Council then established were held in January 1961 and ended in a deadlock. Further elections, held in June, were marked by serious rioting and heavy casualties. Ten seats were won by the Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP), representing mainly the African population; 10 by the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP), representing mainly the Zanzibari Arabs; and 3 by the Zanzibar and Pemba People's Party (ZPPP), an offshoot of the ZNP. The ZNP and ZPPP combined to form a government with Mohammed Shamte Hamadi as chief minister.

A constitutional conference held in London in 1962 was unable to fix a date for the introduction of internal self-government or for independence, because of failure to agree on franchise qualifications, the number of elected seats in the legislature, and the timing of the elections. An independent commission, however, subsequently delimited new constituencies and recommended an increase in the numbers of the Legislative Council, which the council accepted, also agreeing to the introduction of universal adult suffrage. Internal self-government was established in June 1963, and elections held the following month resulted in a victory for the ZNP–ZPPP coalition, which won 18 seats, the ASP winning the remaining 13. Final arrangements for independence were made at a conference in London in September. In October it was agreed that the Kenya coastal strip—a territory that extended 10 miles inland along the Kenya coast from the Tanganyika frontier to Kipini and that had long been administered by Kenya although nominally under the sovereignty of Zanzibar—would become an integral part of Kenya on that country's attainment of independence.

Independence

On December 10, 1963, Zanzibar achieved independence as a member of the Commonwealth. In January 1964 the Zanzibar government was overthrown by an internal revolution, Sayyid Jamshid ibn Abdullah (who had succeeded to the sultanate in July 1963 on his father's death) was deposed, and a republic was proclaimed.

Although the revolution was carried out by only about 600 armed men under the leadership of the communist-trained “field marshal” John Okello, it won considerable support from the African population. Thousands of Arabs were massacred in riots, and thousands more fled the island. Sheikh Abeid Amani Karume, leader of the Afro-Shirazi Party, was installed as president of the People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba. Sheikh Abdulla Kassim Hanga was appointed prime minister, and Abdul Raḥman Mohammed (“Babu”), leader of the new left-wing Umma (The Masses) Party (formed by defectors from the ZNP), became minister for defense and external affairs. Pending the establishment of a new constitution, the cabinet and all government departments were placed under the control of a Revolutionary Council of 30 members, which was also vested with temporary legislative powers. Zanzibar was proclaimed a one-party state. Measures taken by the new government included the nationalization of all land, with further powers to confiscate any immovable property without compensation except in cases of undue hardship.

The United Republic

The Tanganyikan constitution was amended in 1962, and Julius Nyerere (Nyerere, Julius) became executive president of the Republic of Tanganyika. In 1963 TANU was declared the only legal party, but voters in each constituency were often offered a choice between more than one TANU candidate in parliamentary elections. That this arrangement amounted to something more than lip service to the idea of democracy was demonstrated in 1965 and in subsequent elections when, although Nyerere was reelected again and again as the sole candidate for president, a considerable number of legislators, including cabinet ministers, lost their seats.

An army mutiny was suppressed in January 1964 only after the president had reluctantly sought the assistance of British marines. Nyerere's authority was quickly restored, however, and in April he made an agreement with President Karume of Zanzibar to establish the United Republic of Tanzania, with Nyerere himself as president and Karume as first vice president. On April 26, 1964, the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar was founded. (Despite unification, for years Zanzibar continued to pursue its own policies, paying little attention to mainland practices.)

Nyerere's chief external task was to convince the outside world, particularly the Western powers, that Tanzania's foreign policy was to be one of nonalignment; but the overt involvement of the Eastern bloc in Zanzibar, as well as Nyerere's own insistence that to rectify the imbalance created in the colonial era Tanzania must turn more to the East for aid, did little to make the task easier. The high moral tone taken by the president over Britain's role in Rhodesia and over the supply of British (British Empire) arms to South Africa also strained the bonds of friendship between the two countries, with Tanzania severing diplomatic relations with Britain from 1965 to 1968. The consequent loss of aid from Britain was more than made good by help from Eastern countries, notably from China, which culminated in 1970 in the offer of an interest-free Chinese loan to finance the construction of a railway line linking Dar es Salaam with Zambia.

Though Nyerere fully appreciated the generous assistance his country was receiving, he was anxious to impress upon his countrymen the need for maximum self-reliance. Political freedom, he insisted, was useless if the country was to be enslaved by foreign investors. His views were formulated in the Arusha Declaration of February 5, 1967. The resources of the country, Nyerere said, were owned by the whole people and were held in trust for their descendants. The leaders must set an example by rejecting the perquisites of a capitalist system and should draw only one salary. Banks must be nationalized, though compensation would be given to shareholders; the same would apply to the more important commercial companies. Agriculture, however, was the key to development, and only greater productivity could hold at bay the spectre of poverty. To give a fillip to his argument, people were to be moved into cooperative villages where they could work together for their mutual benefit.

Nyerere's exhortations did not arouse the enthusiasm for which he had hoped. Individuals resisted his plans for collectivization, and not even the majority of his supporters wholeheartedly adopted his moral stand. The cooperative village scheme failed, bringing additional pressure to bear upon an already desperately weak economy. The sisal industry, one of those nationalized, became badly run down by the mid-1970s because of inefficient management.

Nyerere's criticisms were not reserved for his own people, nor yet for the wealthy nations of the world. In 1968 he challenged the rules of the Organization of African Unity (African Union) (OAU) by recognizing the secession of Biafra from Nigeria, and in 1975 he attacked the OAU for planning to hold its summit meeting in Uganda, where Idi Amin was acting with extreme cruelty. Relations with Kenya also deteriorated, and in 1977 the East African Community ceased to exist after the closure of the Kenyan border. Even more challenging to the OAU's policy of nonintervention in the affairs of member states was the attack launched against Uganda in January 1979 after Amin had invaded the northwestern corner of Tanzania in October 1978. The retention of Tanzanian troops in Uganda for several years after Amin's overthrow, together with Nyerere's long-standing friendship with Uganda's former president, Milton Obote, also led to strained relations with some of Uganda's leaders as well as arousing suspicions in Kenya. Elsewhere in Africa, however, Nyerere was able to play an authoritative role, notably in the negotiations leading to the independence of Zimbabwe and in the formation of an organization of African states to try to resist economic domination by South Africa.

Events in Zanzibar caused continuing concern for the mainland leadership. The arbitrary arrest and punishment of anyone believed to oppose the state gave rise to regret that the constitution of the joint republic prevented the mainland authorities from intervening in the island's affairs where questions of law and justice were involved. The failure to hold elections in Zanzibar also contrasted unfavourably with developments on the mainland. In April 1972 Karume was assassinated by members of the military. His successor, Aboud Jumbe, had been a leading member of Karume's government, and, while his policies did not differ markedly from those of Karume, they appeared to be moving gradually closer into line with mainland practices. The amalgamation of TANU and the ASP under the title of Revolutionary Party (Chama cha Mapinduzi; CCM) early in 1977 was a hopeful sign but was followed by demands for greater autonomy for Zanzibar. This trend was checked when Ali Hassan Mwinyi succeeded Jumbe in 1984 and became president of the joint republic after Nyerere resigned in November 1985; however, in the late 1980s dissent resurfaced in Zanzibar, culminating in the revelation in January 1993 that Zanzibar had joined the Organization of the Islamic Conference. Criticism on the mainland forced its withdrawal later that year.

Mwinyi inherited an economy suffering from the country's lack of resources, the fall in world prices for Tanzanian produce, the rise in petroleum prices, and inefficient management. An acute shortage of food added still further to his problems. Though he promised to follow Nyerere's policy of self-reliance, Mwinyi soon concluded that his predecessor's resistance to foreign aid could no longer be sustained. In accepting an offer of assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1986, Mwinyi adopted some structural reforms and furthered the devaluation of the currency begun in 1984 by Nyerere, who also had denationalized the state-run sector of the sisal industry in 1985. Moreover, private enterprise had been allowed to take over other areas of business.

In May 1992 the constitution was amended to provide for a multiparty political system, and in 1995 the first national elections under this system were held; Benjamin Mkapa of the CCM was elected president. Mkapa continued the economic reforms pursued by his predecessors. Beginning in the mid-1990s and continuing into the 2000s, Tanzania's already-tenuous economy and food supply were strained by the number of refugees (refugee) arriving from the neighbouring countries of Rwanda, Burundi, and Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo); the country eventually requested international aid to assist with the care of the refugees. Meanwhile, in 1998, a bomb attack by terrorists (terrorism) on the United States embassy in Dar es Salaam left 11 people dead and many more injured.

Mkapa was reelected in late 2000 amid allegations of electoral fraud in Zanzibar. Several violent demonstrations followed, including one in January 2001 where police intervention resulted in at least 40 people dead and 100 people injured. Zanzibar also experienced escalating Islamic militancy. Several demonstrations, violent attacks, and bombings in the 2000s were attributed to a few radical organizations protesting the government's refusal to comply with their extremist views. In late 2004, 10 people were killed in Dar es Salaam by the Indian Ocean tsunami; the government was criticized for not doing enough to warn the public about the impending threat. During Mkapa's second term, the government continued to focus on improving the country's economy. After more than a decade of preparation, Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya launched the East African Community Customs Union in 2005, in an effort to stimulate economic activity in the region.

In the early 21st century Tanzania continued on the long path of economic advancement while also dealing with such issues as increasing religious and political tension, providing care for a large refugee population, and having enough food for its own citizens. Tanzania continued to maintain positive relationships with foreign countries and international organizations, many of which provided assistance in addressing these matters.

Additional Reading

Geography

Spatial aspects of resources and development are found in the official Atlas of Tanzania, 2nd ed. (1976); and the more comprehensive Tanzania in Maps, ed. by Leonard Berry (1971). Juhani Koponen, People and Production in Late Precolonial Tanzania: History and Structures (1988), provides a demographic study of precolonial Tanzania; Abdul Sheriff, Slaves, Spices, & Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire with the World Economy, 1770–1873 (1987), gives a detailed history. Issa G. Shivji, Law, State, and the Working Class in Tanzania, c. 1920–1964 (1986), traces the creation of a working class during the colonial period. Deborah Fahy Bryceson, Food Insecurity and the Social Division of Labour in Tanzania, 1919–85 (1990), a thematic history of Tanzania, traces the development of the market, state, and client networks in relation to the fluctuation of the country's food supply. Jannik Boesen et al. (eds.), Tanzania: Crisis and Struggle for Survival (1986), collects articles on the rural economy written by a group of Scandinavian authors. Andrew Coulson, Tanzania: A Political Economy (1982), is an interpretive account.

History

I.N. Kimambo and A.J. Temu (eds.), A History of Tanzania (1969), contains essays on political history from earliest times to independence. John Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika (1979), is a comprehensive, documented, and scholarly general history from 1800 to 1961, mainly political but also economic and social, and Tanganyika Under German Rule, 1905–1912 (1969), studies in detail the early colonial history. John Charles Hatch, Tanzania (1972), by a sympathetic socialist writer, profiles the emergent country before and after independence. Andrew Roberts (ed.), Tanzania Before 1900 (1968), collects essays on the history of several ethnic groups before the colonial period. Hugh W. Stephens, The Political Transformation of Tanganyika, 1920–67 (1968), studies Tanganyika's political progress to independence. Justinian Rweyemamu, Underdevelopment and Industrialization in Tanzania: A Study of Perverse Capitalist Industrial Development (1973), critically views colonial economic policy and its outcome. Rodger Yeager, Tanzania: An African Experiment, 2nd ed., rev. and updated (1989), outlines the problems of independent Tanzania. John Gray, History of Zanzibar, from the Middle Ages to 1856 (1962, reprinted 1975), offers a detached, scholarly study by a former chief justice of Zanzibar. Anthony Clayton, The Zanzibar Revolution and Its Aftermath (1981), gives a preliminary but acute assessment of the causes and immediate effects of the revolution of 1964.

- Tangub

- Tangun

- Tanguy, Yves

- Tang Yin

- Tani Bunchō

- Tanimbar Islands

- Tani Ryōko

- Tanis

- tanistry

- Tanit

- Tanizaki Jun'ichirō

- Tanizaki Prize

- tank

- tanka

- tankard

- tank destroyer

- tanker

- tank landing ship

- Tankred Dorst

- Tan Malaka, Ibrahim Datuk

- Tanna

- tanna

- Tannenberg, Battle of

- Tannenberg, David

- Tanner, Henry Ossawa